Chapter 17 Managing Pediatric and Neonatal Abdominal Wall Defects ![]()

1 Clinical Anatomy

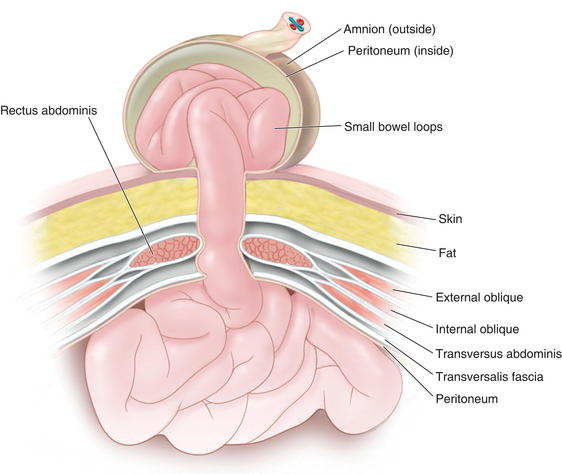

In a patient with an omphalocele (also known as exomphalos) (Fig.17-1), the bowel and viscera, covered by a membrane composed of visceral peritoneum, Wharton jelly, and amnion, herniate through a central defect (≥4 cm) at the umbilical ring. The viscera extend into the base of the umbilical cord and the umbilical cord inserts into the apex of the omphalocele sac. The sac may contain loops of small bowel, large intestine, stomach, and liver (in 50% of cases). These viscera are otherwise functionally normal.

In a patient with an omphalocele (also known as exomphalos) (Fig.17-1), the bowel and viscera, covered by a membrane composed of visceral peritoneum, Wharton jelly, and amnion, herniate through a central defect (≥4 cm) at the umbilical ring. The viscera extend into the base of the umbilical cord and the umbilical cord inserts into the apex of the omphalocele sac. The sac may contain loops of small bowel, large intestine, stomach, and liver (in 50% of cases). These viscera are otherwise functionally normal. Omphalocele is a congenital abnormality and is often associated with other anomalies and syndromes in 60% to 70% of cases. These include Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, Cantrell pentalogy, exstrophy of the bladder/cloaca, and chromosomal trisomies such as Down syndrome. The most common anomalies discovered are cardiac and gastrointestinal.

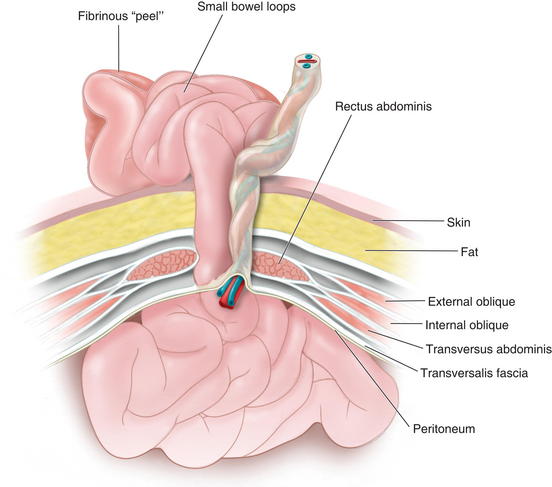

Omphalocele is a congenital abnormality and is often associated with other anomalies and syndromes in 60% to 70% of cases. These include Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome, Cantrell pentalogy, exstrophy of the bladder/cloaca, and chromosomal trisomies such as Down syndrome. The most common anomalies discovered are cardiac and gastrointestinal. In patients with gastroschisis (Fig.17-2), the small bowel freely protrudes, without an overlying sac, through a smaller defect (<4 cm) at the junction between the umbilicus and the skin. The defect is almost always to the right of the umbilicus. The herniated contents may include small bowel, stomach, bladder, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and testes.

In patients with gastroschisis (Fig.17-2), the small bowel freely protrudes, without an overlying sac, through a smaller defect (<4 cm) at the junction between the umbilicus and the skin. The defect is almost always to the right of the umbilicus. The herniated contents may include small bowel, stomach, bladder, fallopian tubes, ovaries, and testes. Unlike omphalocele, gastroschisis is not congenital. It is thought to be related to an in utero vascular accident. For that reason, gastroschisis is associated with small bowel atresias, which also are believed to be caused by in utero vascular accidents.

Unlike omphalocele, gastroschisis is not congenital. It is thought to be related to an in utero vascular accident. For that reason, gastroschisis is associated with small bowel atresias, which also are believed to be caused by in utero vascular accidents. Both omphalocele and gastroschisis are associated with intestinal malrotation, prematurity, and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR).

Both omphalocele and gastroschisis are associated with intestinal malrotation, prematurity, and intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR). The incidence of omphalocele is 1 in 5000 live births while that of gastroschisis is 1 in 2500 live births. Furthermore, mothers of infants with omphalocele are, on average, 10 years older than those with gastroschisis.

The incidence of omphalocele is 1 in 5000 live births while that of gastroschisis is 1 in 2500 live births. Furthermore, mothers of infants with omphalocele are, on average, 10 years older than those with gastroschisis. It is important to differentiate a ruptured omphalocele sac, which occurs in 10% to 18% of patients with omphalocele, from gastroschisis because this distinction may affect clinical management. Although the initial treatment for these two entities is the same, the search for other associated conditions is affected.

It is important to differentiate a ruptured omphalocele sac, which occurs in 10% to 18% of patients with omphalocele, from gastroschisis because this distinction may affect clinical management. Although the initial treatment for these two entities is the same, the search for other associated conditions is affected. In gastroschisis, due to exposure to amniotic fluid and compromised blood supply, the small bowel may become thick, shortened, edematous, discolored, and covered with fibrinous exudates (also known as a “peel”). This may reduce the malleability of the bowel and make manual reduction more difficult. Furthermore, extensive peel is thought to lead to a prolonged ileus after bowel reduction.

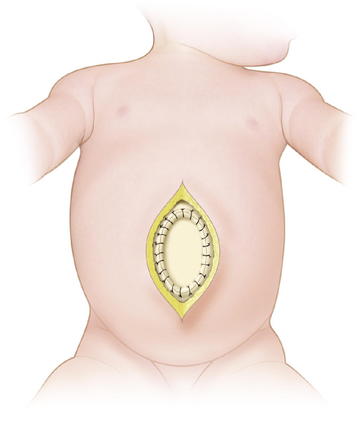

In gastroschisis, due to exposure to amniotic fluid and compromised blood supply, the small bowel may become thick, shortened, edematous, discolored, and covered with fibrinous exudates (also known as a “peel”). This may reduce the malleability of the bowel and make manual reduction more difficult. Furthermore, extensive peel is thought to lead to a prolonged ileus after bowel reduction. Omphalocele is due to the primary failure of the developing intestines to return to the abdominal cavity after migration into the umbilical cord during weeks 6 to 12 of gestation. Figure 17-3 depicts a cross-sectional diagram of the anatomy seen in omphalocele. The abdominal muscles are otherwise normally developed.

Omphalocele is due to the primary failure of the developing intestines to return to the abdominal cavity after migration into the umbilical cord during weeks 6 to 12 of gestation. Figure 17-3 depicts a cross-sectional diagram of the anatomy seen in omphalocele. The abdominal muscles are otherwise normally developed. Gastroschisis is believed to be caused by involution of the right umbilical vein during the fourth week of development. The resulting ischemia leads to a full-thickness defect in the musculature of the abdominal wall. Figure 17-4 shows a cross-sectional diagram of the anatomy seen in gastroschisis.

Gastroschisis is believed to be caused by involution of the right umbilical vein during the fourth week of development. The resulting ischemia leads to a full-thickness defect in the musculature of the abdominal wall. Figure 17-4 shows a cross-sectional diagram of the anatomy seen in gastroschisis.2 Preoperative Considerations

Both omphalocele and gastroschisis may be suspected prenatally with an elevated maternal serum α-fetoprotein (although this level can be normal or elevated because of other conditions) and can be diagnosed readily by prenatal ultrasonography in 75% to 80% of cases (after 14 weeks’ gestation when the fetal midgut returns to the abdomen). They can be differentiated sonographically by the presence of a sac, location of the defect, and presence of additional abnormalities. These methods have increasingly led to detection before birth and allow for prenatal education and family counseling.

Both omphalocele and gastroschisis may be suspected prenatally with an elevated maternal serum α-fetoprotein (although this level can be normal or elevated because of other conditions) and can be diagnosed readily by prenatal ultrasonography in 75% to 80% of cases (after 14 weeks’ gestation when the fetal midgut returns to the abdomen). They can be differentiated sonographically by the presence of a sac, location of the defect, and presence of additional abnormalities. These methods have increasingly led to detection before birth and allow for prenatal education and family counseling. If an omphalocele is discovered, it is important to search for associated anomalies by performing an amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling for karyotype analysis, as well as fetal echocardiography to find structural abnormalities.

If an omphalocele is discovered, it is important to search for associated anomalies by performing an amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling for karyotype analysis, as well as fetal echocardiography to find structural abnormalities. Steps are taken to stabilize the infant immediately following birth. A careful assessment of the oxygenation and ventilation is done because of an association with pulmonary hypoplasia, and the child is intubated if in respiratory distress. A nasogastric tube is placed to decompress the stomach. The patient is placed on the right side to preserve bowel perfusion. The sac is covered with moist gauze and plastic wrap. Care must be taken when handling the viscera because too much pressure can lead to abdominal compartment syndrome and mishandling of the intestines can lead to volvulus. These infants are often hypovolemic and are given aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation resulting from both evaporative and third-space fluid losses. With gastroschisis (or ruptured omphalocele) prophylactic broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics are administered. Temperature is controlled with a heating lamp. Routine blood work is ordered and a detailed physical exam is performed.

Steps are taken to stabilize the infant immediately following birth. A careful assessment of the oxygenation and ventilation is done because of an association with pulmonary hypoplasia, and the child is intubated if in respiratory distress. A nasogastric tube is placed to decompress the stomach. The patient is placed on the right side to preserve bowel perfusion. The sac is covered with moist gauze and plastic wrap. Care must be taken when handling the viscera because too much pressure can lead to abdominal compartment syndrome and mishandling of the intestines can lead to volvulus. These infants are often hypovolemic and are given aggressive intravenous fluid resuscitation resulting from both evaporative and third-space fluid losses. With gastroschisis (or ruptured omphalocele) prophylactic broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics are administered. Temperature is controlled with a heating lamp. Routine blood work is ordered and a detailed physical exam is performed. With an intact omphalocele sac, surgical repair is not immediately necessary. Conservative treatment allows time for the diagnosis of associated conditions and lowers the risk of increased intraabdominal pressure and wound complications associated with aggressive closure. However, with gastroschisis or a ruptured omphalocele, urgent surgical repair is required.

With an intact omphalocele sac, surgical repair is not immediately necessary. Conservative treatment allows time for the diagnosis of associated conditions and lowers the risk of increased intraabdominal pressure and wound complications associated with aggressive closure. However, with gastroschisis or a ruptured omphalocele, urgent surgical repair is required. With omphalocele, patients can undergo primary closure, staged closure, or nonoperative management with late closure. Those with gastroschisis may similarly undergo primary closure, or, if the abdominal cavity is too small to accommodate the protuberant bowel, staged closure. Infants with gastroschisis also may be able to undergo the recently developed sutureless repair.

With omphalocele, patients can undergo primary closure, staged closure, or nonoperative management with late closure. Those with gastroschisis may similarly undergo primary closure, or, if the abdominal cavity is too small to accommodate the protuberant bowel, staged closure. Infants with gastroschisis also may be able to undergo the recently developed sutureless repair.3 Operative Steps

1 Omphalocele

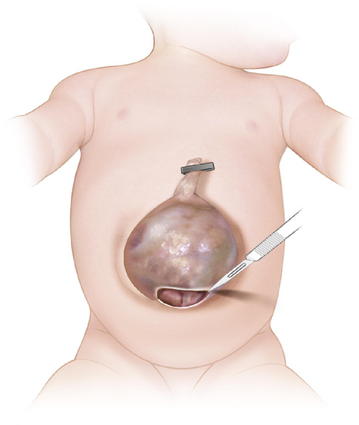

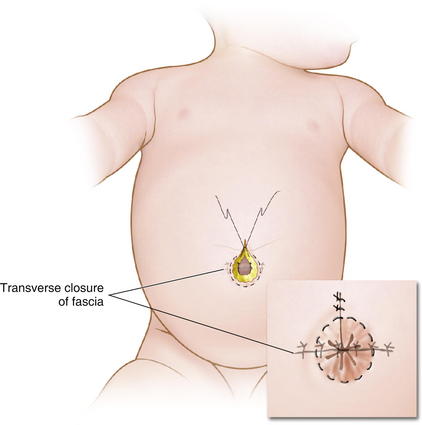

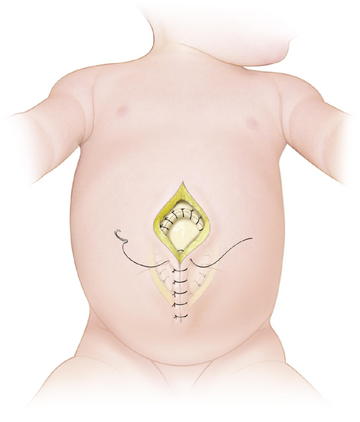

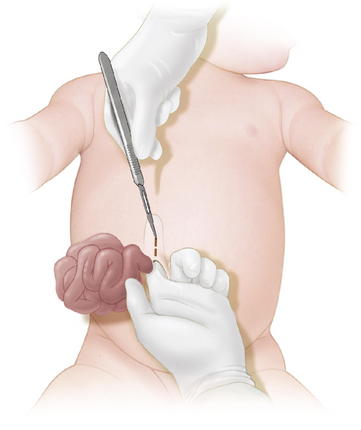

When possible, primary closure should be performed. This is sometimes possible for small or moderately sized defects. The omphalocele sac is excised (Fig.17-5). The umbilical arteries and vein are identified and ligated. The skin is then undermined enough for a secure fascial closure. The viscera are reduced. And the fascia is closed, usually in a transverse fashion. The skin often can be closed using a purse-string suture to try to recreate an umbilicus (Fig.17-6).

When possible, primary closure should be performed. This is sometimes possible for small or moderately sized defects. The omphalocele sac is excised (Fig.17-5). The umbilical arteries and vein are identified and ligated. The skin is then undermined enough for a secure fascial closure. The viscera are reduced. And the fascia is closed, usually in a transverse fashion. The skin often can be closed using a purse-string suture to try to recreate an umbilicus (Fig.17-6). Larger defects require gradual reduction of the viscera. There are several methods for staged closure of an omphalocele.

Larger defects require gradual reduction of the viscera. There are several methods for staged closure of an omphalocele. For the Gross technique, developed in 1948, the omphalocele sac is excised. The skin is undermined enough to provide minimal tension. Prosthetic material may be needed to bridge the fascial defect (Fig.17-7). The skin is then closed over the defect (Fig.17-8). The resulting ventral hernia is then repaired at a later time. In recent years, many surgeons who use this approach are using biologic mesh material for closure.

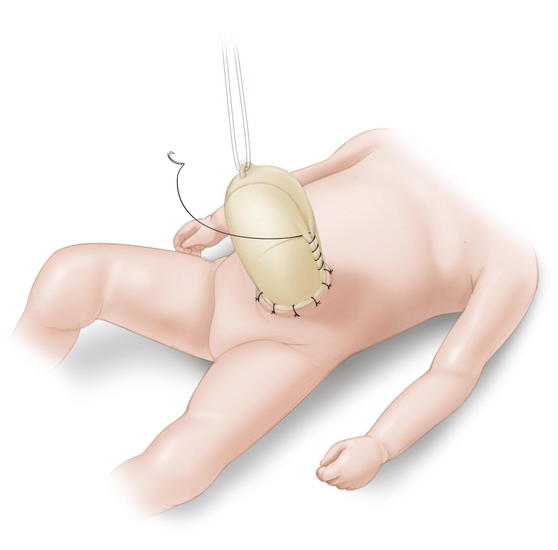

For the Gross technique, developed in 1948, the omphalocele sac is excised. The skin is undermined enough to provide minimal tension. Prosthetic material may be needed to bridge the fascial defect (Fig.17-7). The skin is then closed over the defect (Fig.17-8). The resulting ventral hernia is then repaired at a later time. In recent years, many surgeons who use this approach are using biologic mesh material for closure. The Schuster technique, developed in 1967, is particularly useful for large or ruptured omphaloceles. This technique involves using a silo to gradually reduce the herniated viscera over several days to a week. As much of the viscera as possible are returned to the abdomen. A nonabsorbable material such as silastic sheeting can be used as a silo, secured to either the fascia or skin with nonabsorbable suture. The silo is then closed over the top of the viscera and suspended perpendicularly to avoid kinks in the intestine, allowing gravity to pull the viscera back into the abdomen (Fig.17-9). The silo is tightened daily to assist in visceral reduction. Once the viscera are reduced within the abdominal cavity, the silo is removed and the fascia and skin are closed.

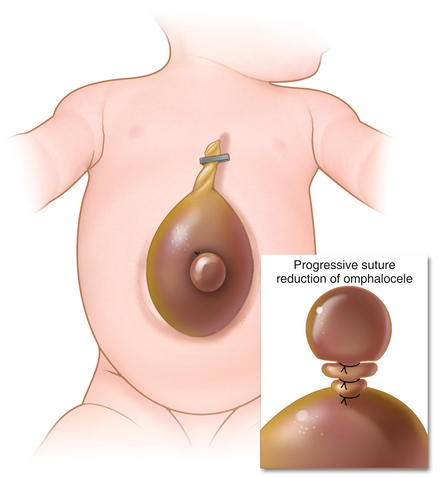

The Schuster technique, developed in 1967, is particularly useful for large or ruptured omphaloceles. This technique involves using a silo to gradually reduce the herniated viscera over several days to a week. As much of the viscera as possible are returned to the abdomen. A nonabsorbable material such as silastic sheeting can be used as a silo, secured to either the fascia or skin with nonabsorbable suture. The silo is then closed over the top of the viscera and suspended perpendicularly to avoid kinks in the intestine, allowing gravity to pull the viscera back into the abdomen (Fig.17-9). The silo is tightened daily to assist in visceral reduction. Once the viscera are reduced within the abdominal cavity, the silo is removed and the fascia and skin are closed. Sequential sac ligation is when the natural omphalocele sac itself is used as a silo. It requires a sac that is strong and not adherent to the viscera. Traction is applied to the sac to slowly reduce its contents. As the viscera are reduced into the abdominal cavity, the sac is twisted and ligated with umbilical ties (Fig.17-10).

Sequential sac ligation is when the natural omphalocele sac itself is used as a silo. It requires a sac that is strong and not adherent to the viscera. Traction is applied to the sac to slowly reduce its contents. As the viscera are reduced into the abdominal cavity, the sac is twisted and ligated with umbilical ties (Fig.17-10). Tissue expanders also have been used successfully in the closure of giant omphaloceles. The tissue expander is placed within the peritoneal cavity and slowly inflated with saline over several weeks, increasing the abdominal domain. The infant is eventually taken to the operating room (OR) for visceral reduction and fascial/skin closure.

Tissue expanders also have been used successfully in the closure of giant omphaloceles. The tissue expander is placed within the peritoneal cavity and slowly inflated with saline over several weeks, increasing the abdominal domain. The infant is eventually taken to the operating room (OR) for visceral reduction and fascial/skin closure. Nonoperative (escharotic) therapy is an option for those patients who are not good candidates for surgical intervention (premature, chromosomal abnormalities, significant congenital heart disease, or pulmonary hypoplasia) and the author’s preferred option for giant omphaloceles. The omphalocele sac is painted with an escharotic material, such as silver sulfadiazine. The authors have also used an Aquacel dressing (ConvaTec, Skillman, NJ) for this purpose. These materials prevent infection, form granulation tissue, and allow the sac surface to eventually epithelialize and contract over several months. The resulting ventral hernia is then electively repaired once the underlying cardiac, pulmonary, and/or other conditions have improved.

Nonoperative (escharotic) therapy is an option for those patients who are not good candidates for surgical intervention (premature, chromosomal abnormalities, significant congenital heart disease, or pulmonary hypoplasia) and the author’s preferred option for giant omphaloceles. The omphalocele sac is painted with an escharotic material, such as silver sulfadiazine. The authors have also used an Aquacel dressing (ConvaTec, Skillman, NJ) for this purpose. These materials prevent infection, form granulation tissue, and allow the sac surface to eventually epithelialize and contract over several months. The resulting ventral hernia is then electively repaired once the underlying cardiac, pulmonary, and/or other conditions have improved.2 Gastroschisis

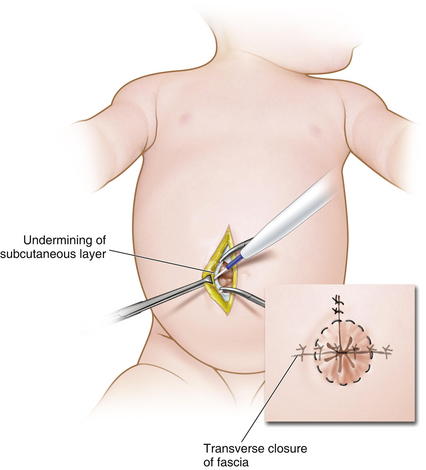

Primary closure of gastroschisis is possible in a majority of cases. Muscle relaxation is often used to assist with visceral reduction. Also, decompression of the stomach or bowel may aid in reducing the volume of the intestines. It may be difficult to reduce the herniated contents through a small defect, and thus, the neck of the defect may need to be enlarged superiorly (Fig.17-11). The bowel must be examined for possible atresias or perforations. The skin is then undermined enough to provide a secure closure. Because the risk of subsequent umbilical hernia is high after gastroschisis repair, the fascia lateral to the umbilical ring should be identified and used for placement of the suture (Fig.17-12). Care must be taken to avoid abdominal compartment syndrome by putting too much pressure on the reduced intestines. If atresia is noted, the bowel is reduced at the first operation and a second operation is done 4 to 6 weeks later to correct the atresia as the intraabdominal inflammation resolves.

Primary closure of gastroschisis is possible in a majority of cases. Muscle relaxation is often used to assist with visceral reduction. Also, decompression of the stomach or bowel may aid in reducing the volume of the intestines. It may be difficult to reduce the herniated contents through a small defect, and thus, the neck of the defect may need to be enlarged superiorly (Fig.17-11). The bowel must be examined for possible atresias or perforations. The skin is then undermined enough to provide a secure closure. Because the risk of subsequent umbilical hernia is high after gastroschisis repair, the fascia lateral to the umbilical ring should be identified and used for placement of the suture (Fig.17-12). Care must be taken to avoid abdominal compartment syndrome by putting too much pressure on the reduced intestines. If atresia is noted, the bowel is reduced at the first operation and a second operation is done 4 to 6 weeks later to correct the atresia as the intraabdominal inflammation resolves. As with omphalocele, staged closure, can be used when reducing the herniated viscera is too difficult or produces too much intraabdominal pressure. A silo is used to gradually reduce the bowel by decreasing the swelling and rigidity of the inflamed bowel and progressively stretching the abdominal cavity. The silo also prevents electrolyte, fluid, and heat losses. Recently, preformed spring-loaded silos that can be placed at the bedside without sutures or anesthesia have shown to be associated with fewer ventilator days, more rapid return of bowel function, and fewer complications (Fig.17-13).

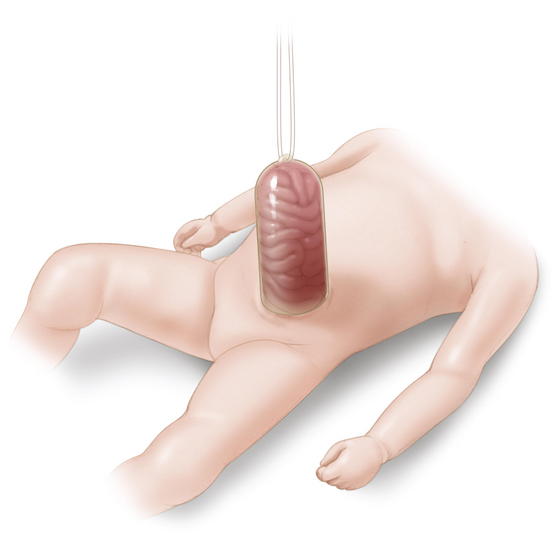

As with omphalocele, staged closure, can be used when reducing the herniated viscera is too difficult or produces too much intraabdominal pressure. A silo is used to gradually reduce the bowel by decreasing the swelling and rigidity of the inflamed bowel and progressively stretching the abdominal cavity. The silo also prevents electrolyte, fluid, and heat losses. Recently, preformed spring-loaded silos that can be placed at the bedside without sutures or anesthesia have shown to be associated with fewer ventilator days, more rapid return of bowel function, and fewer complications (Fig.17-13). Sutureless repair, developed by Sandler et al. (2004), allows the defect to naturally heal over the reduced bowel. The bowel is first manually reduced into the abdominal cavity (Fig.17-14, A, B). The umbilical cord is wrapped into a coil over the defect. The area is covered with a 2 × 2 gauze sponge and Tegaderm dressing (3M, St. Paul, MN) and allowed to heal over several days (Fig.17-14, C, D). This type of repair uses no sutures, eliminates the need for a trip to the OR, and may be cosmetically superior to traditional surgical repair.

Sutureless repair, developed by Sandler et al. (2004), allows the defect to naturally heal over the reduced bowel. The bowel is first manually reduced into the abdominal cavity (Fig.17-14, A, B). The umbilical cord is wrapped into a coil over the defect. The area is covered with a 2 × 2 gauze sponge and Tegaderm dressing (3M, St. Paul, MN) and allowed to heal over several days (Fig.17-14, C, D). This type of repair uses no sutures, eliminates the need for a trip to the OR, and may be cosmetically superior to traditional surgical repair.4 Postoperative Care

Postoperative care requires the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Larger defects require mechanical ventilation for days to weeks. It is important to monitor for signs of abdominal compartment syndrome (hypotension, oliguria, acidosis, intestinal ischemia, liver dysfunction) with intragastric or intravesical catheters. The intraabdominal pressure should not be above 15 to 20 mm Hg.

Postoperative care requires the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Larger defects require mechanical ventilation for days to weeks. It is important to monitor for signs of abdominal compartment syndrome (hypotension, oliguria, acidosis, intestinal ischemia, liver dysfunction) with intragastric or intravesical catheters. The intraabdominal pressure should not be above 15 to 20 mm Hg. After repair, ileus is common, resolving more quickly in patients with omphalocele than those with gastroschisis. A nasogastric tube is necessary initially and total parenteral nutrition is started early. In fact, many surgeons place a central venous catheter at the time of operation for this purpose. Once bowel function has returned, enteral feedings can begin. Elemental formula is best tolerated and once the infant’s caloric intake is adequate (usually around 3 to 4 weeks without complications) the patient is ready for discharge to home.

After repair, ileus is common, resolving more quickly in patients with omphalocele than those with gastroschisis. A nasogastric tube is necessary initially and total parenteral nutrition is started early. In fact, many surgeons place a central venous catheter at the time of operation for this purpose. Once bowel function has returned, enteral feedings can begin. Elemental formula is best tolerated and once the infant’s caloric intake is adequate (usually around 3 to 4 weeks without complications) the patient is ready for discharge to home. Gastroschisis also is associated with morbidity and mortality related to gastrointestinal dysfunction, such as short bowel syndrome and sepsis from intraabdominal, wound, or central line infection.

Gastroschisis also is associated with morbidity and mortality related to gastrointestinal dysfunction, such as short bowel syndrome and sepsis from intraabdominal, wound, or central line infection. With omphalocele, the long-term outcome is most dependent on the associated chromosomal/structural abnormalities with an overall mortality of 10% to 30%. Long-term complications include gastroesophageal reflux disease, feeding disorders, and adhesive bowel obstruction, but most of these issues improve over time. Most individuals without severe associated anomalies grow up to live normal lives.

With omphalocele, the long-term outcome is most dependent on the associated chromosomal/structural abnormalities with an overall mortality of 10% to 30%. Long-term complications include gastroesophageal reflux disease, feeding disorders, and adhesive bowel obstruction, but most of these issues improve over time. Most individuals without severe associated anomalies grow up to live normal lives. The long-term outcome for patients with gastroschisis has dramatically improved over the past few decades because of improved surgical technique and perioperative management, such as the use of staged closure and the availability of total parenteral nutrition. Overall mortality is now <10%, and is most often associated with intestinal atresia. Prognosis is most dependent on the condition of the exteriorized bowel. Those patients with intestinal atresia undergo additional surgical procedures, delayed enteral feedings, and have prolonged hospital stays.

The long-term outcome for patients with gastroschisis has dramatically improved over the past few decades because of improved surgical technique and perioperative management, such as the use of staged closure and the availability of total parenteral nutrition. Overall mortality is now <10%, and is most often associated with intestinal atresia. Prognosis is most dependent on the condition of the exteriorized bowel. Those patients with intestinal atresia undergo additional surgical procedures, delayed enteral feedings, and have prolonged hospital stays.5 Pearls/Pitfalls

If a fetus is discovered to have an abdominal wall defect, there is no evidence to suggest that early delivery or cesarean-section is beneficial. The mode and timing of delivery should be determined by fetal well-being and obstetric considerations. Serial ultrasound exams during pregnancy can aid in evaluating the condition of the bowel and whether the fetus is at risk.

If a fetus is discovered to have an abdominal wall defect, there is no evidence to suggest that early delivery or cesarean-section is beneficial. The mode and timing of delivery should be determined by fetal well-being and obstetric considerations. Serial ultrasound exams during pregnancy can aid in evaluating the condition of the bowel and whether the fetus is at risk. It is important to differentiate omphalocele from gastroschisis because this distinction greatly affects clinical management. A membranous sac covering the viscera is present in omphalocele (unless ruptured) and absent in gastroschisis. Omphalocele is a central defect, whereas gastroschisis is lateral to (usually to the right of) the umbilicus. The herniated viscera in omphalocele may include bowel, stomach, and liver, whereas gastroschisis may involve bowel, stomach, bladder, and gonads.

It is important to differentiate omphalocele from gastroschisis because this distinction greatly affects clinical management. A membranous sac covering the viscera is present in omphalocele (unless ruptured) and absent in gastroschisis. Omphalocele is a central defect, whereas gastroschisis is lateral to (usually to the right of) the umbilicus. The herniated viscera in omphalocele may include bowel, stomach, and liver, whereas gastroschisis may involve bowel, stomach, bladder, and gonads. Omphalocele can be repaired electively, while the presence of associated abnormalities is investigated. However, gastroschisis (and ruptured omphalocele) require urgent surgical repair because these entities leave the infant vulnerable to dehydration, hypothermia, electrolyte abnormalities, and infection.

Omphalocele can be repaired electively, while the presence of associated abnormalities is investigated. However, gastroschisis (and ruptured omphalocele) require urgent surgical repair because these entities leave the infant vulnerable to dehydration, hypothermia, electrolyte abnormalities, and infection. When repairing these abdominal wall defects, care must be taken to avoid too aggressive of a repair, which can potentially lead to abdominal compartment syndrome, causing more complications and putting the remaining bowel at risk. Avoidance of abdominal compartment syndrome decreases the risk of intestinal ischemia, necrotizing enterocolitis, and intestinal perforation, all of which can lead to devastating consequences for a vulnerable infant.

When repairing these abdominal wall defects, care must be taken to avoid too aggressive of a repair, which can potentially lead to abdominal compartment syndrome, causing more complications and putting the remaining bowel at risk. Avoidance of abdominal compartment syndrome decreases the risk of intestinal ischemia, necrotizing enterocolitis, and intestinal perforation, all of which can lead to devastating consequences for a vulnerable infant.Aspelund G.L.J. Abdominal wall defects. Current Paediatrics. 2006:192-198.

Henrich K., Huemmer H.P., Reingruber B., Weber P.G. Gastroschisis and omphalocele: treatments and long-term outcomes. Pediatr Surg Int. 2008;24:167-173.

Langer J.C. Abdominal wall defects. World J Surg. 2003;27:117-124.

Ledbetter D.J. Gastroschisis and omphalocele. Surg Clin North Am. 2006;86:249-260. vii

Mann S., Blinman T.A., Douglas Wilson R. Prenatal and postnatal management of omphalocele. Prenat Diagn. 2008;28:626-632.

Molenaar J.C., Tibboel D. Gastroschisis and omphalocele. World J Surg. 1993;17:337-341.

Puri P.H.M., editor. Pediatric Surgery. Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg, New York, NY, 2006;153-170.

Sandler A., Lawrence J., Meehan J., Phearman L., Soper R. J Pediatr Surg. 2004 May;39(5):738-741.