Chapter 14 Managing chronic risk

Chronic risk as a term is used predominantly to refer to a risk of suicide which remains present in a patient in a sub-acute form but which can become acute from time to time. It is also used for patients with repeated self-harming behaviour which at times is difficult to differentiate from acute suicidal risk. This behaviour is frequently linked to the diagnosis of borderline personality disorder (BPD) but is also seen in other personality disorders, dysthymia and chronic depression. The focus of this chapter is to look at the risk as it relates to patients with BPD although some of the techniques can be utilised in patients with other diagnoses when the same psychodynamic features are present.

• Bateman A, Fonagy P 2006 Mentalization-based Treatment for Borderline Personality Disorder: a Practical Guide. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

• Krawitz R et al 2004 Professionally indicated short-term risk-taking in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Australasian Psychiatry, 12(1):11–22.

• Linehan MM 1993 Cognitive Behavioural Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. The Guilford Press, New York.

Professionally indicated short-term risk-taking

Before embarking on the development of a plan for managing chronic risk, it is timely to remember that a diagnosis of BPD should not be made lightly. It is likely that a patient will have been assessed and treated within a mental health service for some weeks or months before the diagnosis is made and detailed assessments and formulations will have been undertaken. The clinical picture needs to be clear before management approaches for chronic risk can be put in place.

The risks most frequently associated with the BPD diagnosis are self-damaging acts and suicide attempts. Between 70 and 75% of people with BPD have a history of at least one self-injurious act and estimates of suicide rates vary, but tend to be about 9%.1 Given the high frequency of suicide attempts, death by suicide is a genuine risk. This risk has been reported to be of the same magnitude as that noted in patients with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder (BPAD).2 This data highlights the risk clinicians face when working with BPD. Self-harm exists on a continuum with suicide for the patient with BPD.3 The behaviour is not necessarily seen as being risky by patients. It is often the clinician or family member who sees the danger. The dynamic which leads to either self-harming behaviour or attempted suicide is difficult to explain simply. Individuals with BPD can experience a sense of badness which can be overwhelming. Self-harm can be understood as a way of using a physical act to relieve unbearable emotional states. The similarities with entrapment, which is a risk factor for suicide, are clear. Subsequent to the event, the patient often feels relieved and experiences a greater sense of self-coherence. Suicide attempts often occur when the patient is temporarily unable to mentalise (see glossary). The patient often believes that one part of them will survive the suicide attempt and that an alien/bad part will be destroyed.4 Suicidality can vary from zero lethality and intent to un-ambivalent intent.5

For these patients, the behaviour is adaptive until such time that other ways of expressing distress are learned. For patients with BPD, the behaviour is likely to persist over time. This has substantial relevance to the issue of hospitalisation as it is unlikely to change the level of risk substantially. Paradoxically, hospitalisation can increase the risk.6, 7

There are two important factors to consider in deciding how active to be in response to a suicidal crisis:8

1. the short-term risk of suicide if staff do not actively intervene

2. the long-term risk of suicide and of a life not worth living, if staff do actively intervene.

The response to the patient in any given case requires a good knowledge of dynamic risk factors and of the functions of suicidal behaviour for the patient. These are more clearly identified in patients well known to the service. For patients less well known, treatment will be more conservative and active.

Certain responses may in the short term decrease the probability of suicide, but that response may actually increase the likelihood of future suicide.9 When suicidal ideation and threats are enacted because of the consequences they bring — that is, they function to get others actively involved (e.g. get help, solve problems, obtain admission to hospital, etc) — clinicians need to be careful that their response does not inadvertently reinforce the high-risk suicide behaviours they are trying to stop. Conversely when the suicidal behaviour is elicited in response to a situation or stimulus event, rather than by the consequences it brings, the behaviour will not be reinforced by responding to it. The nature of BPD is that the risk is likely to persist over time.

With a chronically suicidal patient, staff can expect a number of repeated suicidal behaviours before that behaviour comes under control. However, ‘it is ultimately essential that the behaviour comes under the patient’s control and not that of staff or of the community’.10 ‘Chronic suicide behaviour can be seen as being a mode of adaptation to life, an extremely common state among individuals with BPD.’11

If the patient is assessed to be an acute risk for suicide, then clinicians are ethically and legally required to take a directive role in preventing the patient from actually committing suicide — management of the short-term crisis is needed until the self-destructive phase passes. In contrast, chronic suicidal states driven by abnormal personality functioning represent a seriously disturbed yet consistent mode of relating to others and the environment by engaging others into assuming responsibility for suicidal behaviour and thus avoiding appropriate levels of personal responsibility for behaviour. Interventions for chronic suicide should assist and teach the patient to again assume realistic self-responsibility. Otherwise, traditional paternalistic and directive interventions may actually reinforce the destructive interpersonal dynamics of the individual with BPD and provoke further suicidal behaviour. ‘Reducing risk to people with personality disorder involves placing a high degree of choice and personal responsibility with the patient.’12

‘For both clinical and ethical/legal reasons, it is important that clinicians recognise the distinction between acute and chronic suicidal states.’13 This differentiation needs to be clearly assessed and documented. If a chronic suicidal state is affirmed, clinicians need to actively employ a treatment approach based on the interpersonal context and avoid the use of traditional management approaches (longer-term voluntary or involuntary hospitalisation). Involuntary hospitalisation should only be considered when the chronic suicidal state crosses the boundary into an acute suicidal state. ‘With the patient’s informed consent, informing family members that their relative is chronically suicidal allows them to have realistic expectations for therapeutic progress.’14

It is important not to treat acute and chronic suicidal behaviour in the same way. Whatever the roots of chronic suicidality, prolonged inpatient care is likely to perpetuate and worsen their difficulties as independent, autonomous functioning decreases and dependency intensifies.15,16 However, there is a dilemma for clinicians:

we understand that repeated hospitalisation is not therapeutic, and that the patient needs to take responsibility for self, but patients certainly do commit suicide and to some extensive degree we are morally responsible for our patients, especially when their judgment is disturbed.17

Such cautionary practice can lead to a worsening downward spiral of regressive attempts to get patients to take responsibility for their lives. Giving responsibility back to the patient, even though the immediate suicide risk may increase for a time, is the best hope.18

When is taking a calculated risk appropriate?19

When the clinician reaches an informed, considered opinion that precautionary, close-monitored management is no longer beneficial and is likely to lead to long-term worsening of the patient’s condition, the responsibility for personal safety should be given back to the patient. This is not only ethically defensible but therapeutically necessary. Clinicians must consider, in making this decision, if depressive, psychotic or substance abuse features have been treated appropriately.

How to take a calculated risk

• Short- and long-term risks and benefits of treatment have been clinically considered and are documented. (See the section on risk/benefit analyses in Chapter 10.) A formal consultation with an experienced colleague documenting support for the treatment plan, acknowledging the hazards of prolonged hospitalisation and that taking calculated risks is in the patient’s best interest, is essential. The risk/benefit analysis should be reviewed regularly.

• The patient is assessed for acute or chronic suicide behaviour and this is documented. By the time clinicians are considering a professionally indicated short-term risk-taking approach, the patient will have (usually) had a history of a standard approach to suicidality and self-harm that will have been counterproductive, with negative outcomes.20

• A reasonable community treatment plan is devised. This should be based on a therapeutic alliance and help the patient to maintain a sense of responsibility without being rejected or rescued. It should include guidelines for crisis clinicians, pathways to respite and hospitalisation and the patient’s individualised crisis strategies. It should be reviewed regularly.

• The patient understands and agrees to the planned treatment, and understands that taking a calculated risk is an important step in the treatment. Documentation must include that the patient is mentally competent to consent. (Depressed mood and delusions do not necessarily impair a patient’s competency to make a reasonable decision. The issue of competency is beyond the scope of this book. Advice should be taken for definitions of competency.)

• Family and close friends need to be fully informed about the treatment plan and the inherent risks and benefits. The risks and benefits of prolonged hospital care should also be explained. The family agreement should be obtained and documented.

• It is important to be able to respond to changed circumstances. Changes in the pattern of suicidality, mental state changes, acute stressors and so forth should lead to an urgent review.

‘At some future time will a malpractice action be brought asserting that overly restrictive, regression–inviting management negligently promoted, not prevented, suicide?’21

There is a paradox in working with potentially suicidal borderline patients. Clinicians require the courage to face the possibility of a patient’s death without losing confidence in their ability or their profession. Patients recognise this courage and grow more confident in its presence. Conversely timidity teaches the patient that life is just as scary as they always thought it was and may heighten the risk of actual suicide.22

Crisis plan

• List and number the usual crisis situations, early warning signs and triggers; that is, feeling like self-harming, actual self-harming.

• Detail, under each crisis, the client’s own response; for example, using self-soothing, coping strategies.

• Detail the mental health service response to each crisis for when the client is unable to manage independently.

Crisis cards, as forms of advanced directives, are sometimes used in these situations.23

Clinical tips at times of crisis25

• make a systematic attempt to place some of the responsibility for the patient’s actions back with the patient with an aim of re-establishing self-control

• make clear that the staff are able and willing to respond to the emergency

• remain calm — anxiety in the therapist reduces his ability to mentalise (see glossary)

• sensitively monitor counter-transference and other responses

• assess the immediacy of the threat and consider it in terms of previous acts of self-harm or suicide attempts

• be aware of the well-known risk factors for suicide (see Table 9.1, page 80–81)

• keep talking to the patient about the feeling and its immediate precipitants

• be clear about the patient’s role whilst the suicide risk remains high

• following the episode, ensure a thorough review in a number of contexts, including individual therapy, group therapy and with the multidisciplinary team (MDT).

Example

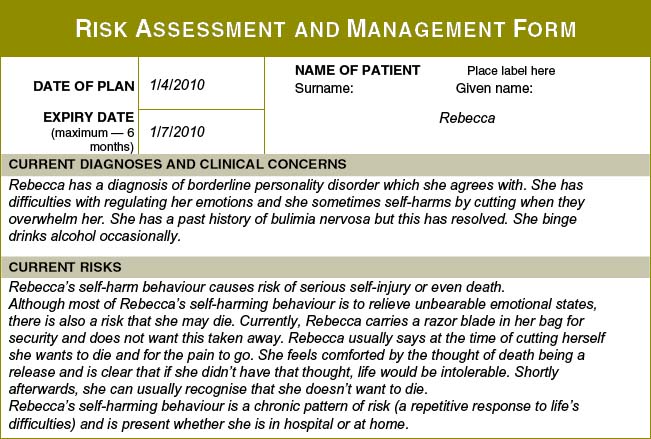

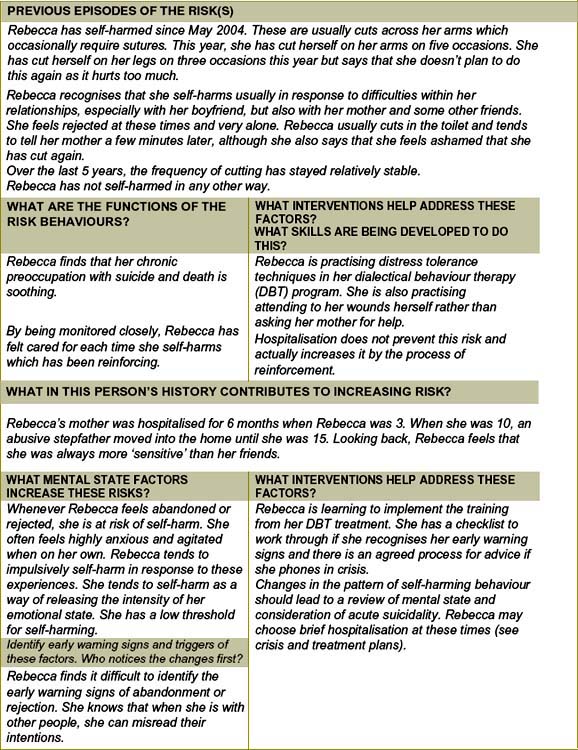

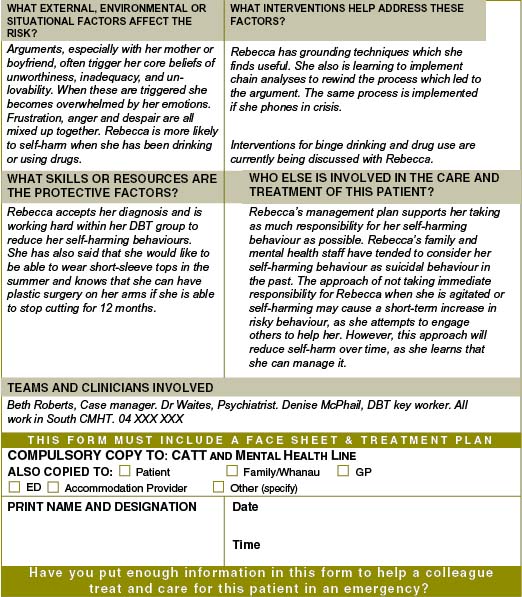

Figure 14.1 provides an example of a completed risk plan. As has been described earlier, these plans should be written using easily understood language, with minimal use of jargon. Descriptions of behaviours and mental states, such as ‘she struggles to like her mum’, are much more useful than using phrases such as ‘she cannot introject good objects’. For patients with BPD, this is especially important as the patient needs to ‘own the plan’ and be an active participant in it.

1 Linehan M.M. Cognitive Behavioural Treatment of Borderline Personality Disorder. New York: The Guilford Press; 1993.

2 Stone M.H. Paradoxes in the Management of Suicidality in Borderline Patients. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 1993;47(2):255–272.

3 Linehan M.M. Suicidal people: One population or two? Annals of New York Academy of Science. 1986;487:16–33.

4 Bateman A., Fonagy P. Mentalization-based Treatment for Borderline Personality Disorder: a Practical Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press,; 2006.

5 Krawitz R, et al. Professionally indicated short-term risk-taking in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Australasian Psychiatry. 2004;12(1):11–22.

6 Maltsberger J.T. Calculated risks in the treatment of intractably suicidal patients. Psychiatry. 1994;57:199–212.

7 Paris J. Is hospitalisation useful for suicidal patients with borderline personality disorder? Journal of Personality Disorder. 2004;18(3):240–247.

11 Fine M.A., Sansone R.A. Dilemmas in the management of suicidal behaviour in individuals with borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychotherapy. 1990;44(2):160–171.

12 Crawford M.J., Price K., Rutter D., Moran P., Tyrer P., Bateman A., Fonagy P., Gibson S., Weaver T. Dedicated community-based services for adults with personality disorder: Delphi study. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2008;193:342–343.

13 Fine and Sansone, above, n 11.

14 Fine and Sansone, above, n 11.

15 Maltsberger J.T. Calculated risks in the treatment of intractably suicidal patients. Psychiatry. 1994;57:199–212.

19 Maltsberger J.T. Calculated risk-taking in the treatment of suicidal patients: ethical and legal problems. Death Studies. 1994;18:439–452.

23 Sutherby K., Szmukler G.I., Halpern A., Alexander M., Thornicroft G., Johnson C., Wright S. A study of ‘crisis cards’ in a community psychiatric service. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1999;100:56–61.

24 Adapted fromBateman A., Fonagy P. Psychotherapy for Borderline Personality Disorder. Oxford: Oxford Medical Publications, Oxford University Press; 2004. Appendix 2.