Chapter 17 Managing adverse outcomes

Adverse events usually originate at a variety of systemic levels: the patient–clinician interaction, the team, the working environment and the organisation. Consideration of all of these factors is required when investigating and preventing adverse outcomes. The liability to make an error is strongly affected by the context and conditions of work, and the chain of events leading to an adverse outcome is usually complex. The root cause may be in several interlocking factors such as the use of locums, communication problems, supervision problems, excessive workload, resource limitations and training deficiencies. Analysis of accidents/adverse outcomes in mental health should explore not just the individual factors but also pre-existing organisational factors.

There are 2 types of errors leading to adverse outcomes:

Active failures

Active failures are those acts or omissions committed by individuals that have an immediate adverse consequence. Where possible, failsafe mechanisms are brought in to guard against human error; for example, sharps boxes or computerised prescribing programs that do not allow excessive doses to be prescribed. Active failures can be divided into three subgroups:

1. Action slips or failures, such as labelling the wrong blood sample. Departure from routine is a major factor in the absent-minded slips of action.1

2. Cognitive failures, such as memory lapses or making mistakes through ignorance.

3. Violations which are deviations from usual operating practice without good reason. These are more likely to occur secondary to low morale, poor modelling from senior staff or inadequate management.

Latent failures

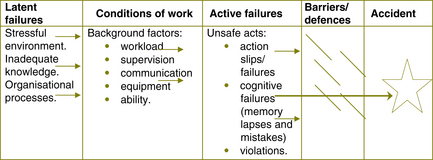

These are the factors that influence staff performance and may precipitate errors and affect patient outcomes. The process of latent failures increasing the likelihood of active failures can be shown diagrammatically (see Figure 17.1).2 The latent failures are transmitted along various organisational and departmental pathways to the workplace where they create local conditions that precipitate errors and violations. This model creates a more complicated picture where the environment in which an adverse event occurs is one where many factors are added, one to another, before the accident happens. Minimising the likelihood of adverse events occurring requires attention at all these levels by all staff, from the most junior to the most senior.

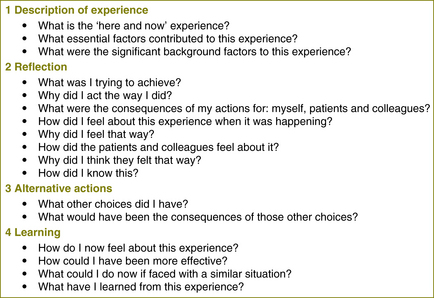

Reviews of this type can benefit from the use of reflective practice at a group level. Using John’s3 model or Rolfe’s et al (2001)4 and asking the questions within a group setting reduces the likelihood of blame occurring and can give a framework for exploring adverse outcomes.

Finally, a summary of error producing conditions ranked in order of increased likelihood of the event happening can be sobering (see Table 17.1).5

| Condition | Risk factor |

|---|---|

Rather than waiting for an adverse outcome, all mental health teams and mental health services should have an ongoing audit cycle asking questions about whether systems and processes are working. As a result of auditing, new procedures can be put in place which, hopefully, will reduce the likelihood of an adverse outcome. Despite best efforts, adverse outcomes will still occur. The immediate thought when adverse outcomes are considered is the death of a patient. However, adverse outcomes can include anything from the intervention not going quite to plan, to an unfortunate admission to hospital that could have been averted if the resources had been available, to a threat of an assault, etc. It is very important to review clinical practice, and that includes clinical risk management, at every opportunity and not only when the worst outcomes occur. This process should include:

Reviewing difficult cases where there were good outcomes will also improve risk management.

Personal structured reflection and review

For example, when working in a crisis situation, after the problem has been resolved, it is good practice to spend a moment or two with your colleagues reviewing how it all went. Ask each other if your communication was good, if you would have done things differently at different stages, and if you would do it differently next time, etc. This creates better working relationships, improves communication and is a marvellous opportunity for reflection whilst the event is still fresh. If working on one’s own, utilising John’s model for structured reflection6

provides a template to follow. It is brief and easily applied and allows an exploration of the conflict and contradictions between what is practised and what is desirable. Figure 17.2 is an adaptation of the model which can easily be adjusted for group settings after critical incidents.

Team reviews

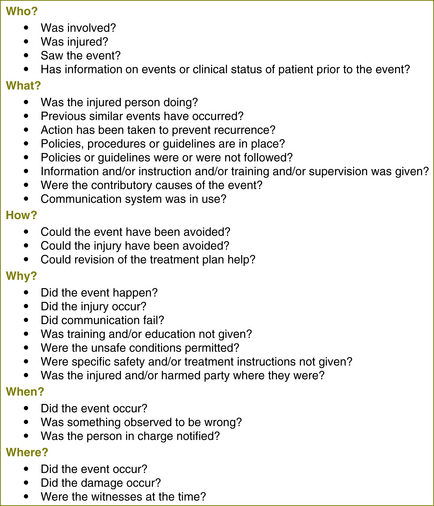

If the adverse outcome is one which does not require to be reported as a sentinel event, it should not simply be ignored but should be reviewed within the multidisciplinary team. Each team will have its own review process that they have decided upon. As described above, some teams choose to use John’s7 model adapted for group processes. These discussions should be carefully facilitated and the environment should be free of blame and supportive but as far as possible should explore the processes that lead to the adverse outcome. Figure 17.3 expands on the process of structured reflection and takes the review process into an analysis of systems issues.

Service review, sentinel events and external reviews

Services will have different definitions of what a sentinel event is. Some services divide sentinel events into categories A, B and C. After a serious event, there is usually a requirement for services to review what happened, to learn from the experience and to mitigate future risk. Through these reviews, system and processes, improvements can occur. Dependent on the nature of the event and also on other factors, such as breach of professional codes, external reviews may occur.

• consideration of whether employees need time off, and the time needed for interviews and planning for return to work

• ongoing service delivery impacts — becoming aware of a service moving into crisis, security needs and the impact of attention by the media.

• Defusing — this may be a simple process of supporting staff whilst they talk about the events of the day before they go home.

• Formal psychological debriefing — although debriefing should be made available, it should be considered with some caution as there are concerns in the literature that this may not be of benefit and, for some clinicians, may cause harm through a process of re-traumatisation.

• Offers of other support services for clinicians. This may include an Employee Assistance Program (EAP) which includes critical incident debriefing and emergency access out of normal hours. Staff may be offered other supports, such as a psychologist on site to drop in and talk to, senior management making themselves available, legal counsel and other additional support options, such as chaplains, etc.

Being involved in an internal or external review is not an easy process for any clinician. However, in a career working in mental health services, it is likely that this will be an experience which few clinicians will escape. Having some knowledge of the interview process and techniques can be comforting and reassuring. Below are some of the usual interview guidelines for the interviewer.

• Make no attempt to blame or find fault — a key skill at interview is to maintain an open mind and listen to the facts, then draw conclusions.

• Welcome and introduce the interviewee and support person to all interviewers.

• Advise staff to be interviewed of:

• Ask the interviewee if they have any questions before commencing the interview.

• Use a comfortable place to ensure the ease of the interviewee.

• Ask for the interviewee’s version of what happened. Only ask necessary questions.

• Avoid leading questions. Concentrate on facts not theory.

• Repeat the interviewee’s account as you (the interviewer) understand it.

• The interviewee may be emotional. Be empathic and reassuring; remind them:

• Close the interview on a positive note. Check for any further questions.

After an interview it is usual for a draft report to be released which should be read carefully for any factual errors.

After a death

The literature focuses mostly on the care and management of families subsequent to a suicide. However, the same general principles apply to other adverse outcomes. In recent times the practice of supporting the bereaved families of patients has become less common, possibly as a result of the fear of litigation. Avoiding survivors’ feelings of abandonment is an integral component of good clinical care and is also desirable, as further family suicides may follow the initial suicide. As well as being good practice, the offering of condolences, saying sorry and being supportive can substantially reduce the risk of further complaints. Saying sorry does not mean accepting blame. ‘Stonewalling’ many increase anger and grief.8 For bereaved family members to experience health practitioners as not caring after the death of a loved one tends to create an assumption that the health practitioner did not care to begin with. The provision of outreach to bereaved families is not only humane, but may be the best preventative measure against future complaints.9

The mental health worker should contact the family as soon as possible, preferably in person.10 The aim is to promote effective grieving, bearing in mind displacement of anger and other issues. Some families of patients who have committed suicide display hostility and the mental health worker needs to prepare for this. Open discussion in a private setting should allow the family to ask questions. Mental health workers need to remember that confidentiality continues beyond death.

The importance of continuing to document interventions even after a patient’s death should not be forgotten. This is still clinical work which needs to be recorded and communicated.

1 Reason J., Mycielska K. Absent-minded? The Psychology of Mental Lapses and Everyday Errors. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1982.

2 Adapted from:Vincent C., Taylor Adams S., Stanhope N. Framework for analysing risk and safety in clinical medicine. British Medical Journal. 1998;316:1154–1157.

3 Johns C. Achieving effective work as a professional activity. In: Schober J.E., Hinchliff S.M. Towards Advanced Nursing Practice. London: Arnold, 1995.

4 Rolfe G., Freshwater D., Jasper M. Critical Reflection for Nursing and the Helping Professions. Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan; 2001.

5 Adapted fromWilliams J. A database method for assessing and reducing human error to improve operational performance. In: Hagen W., ed. ILEEE Fourth Conference on Human Factors and Power Plants. New York: Institute for Electrical and Electronic Engineers; 1988:200–231.

8 Litman R.E. Hospital suicide: lawsuits and standards. Suicide and Life Threatening Behaviour. 1982;12:212–220.

9 Rachlin S. Double jeopardy: suicide and malpractice. General Hospital Psychiatry. 1984;6:302–307.

10 Kaye N.S., Soreff S.M. The psychiatrist’s role, responses and responsibilities when a patient commits suicide. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1991;148:739–743.