Chapter 3 Management of the Patient with Rhinitis

Types of Rhinitis

Rhinitis has traditionally been classified into two broad categories: allergic rhinitis, which implies a rhinitis primarily related to immune-mediated inflammation; and nonallergic rhinitis, which implies a nonimmune mechanism that triggers the patient’s symptoms. While much is understood and has been written about the pathophysiology, diagnosis and treatment of allergic rhinitis, a relative paucity of information is present for nonallergic rhinitis. In addition, many patients experience symptoms that are triggered by both immune and nonimmune mechanisms, and these patients are often classified as having mixed rhinitis, with characteristics of both allergic and nonallergic disease. Recognizing both allergic and nonallergic patterns in rhinitis is essential for the clinician in recommending appropriate treatment plans for patients experiencing nasal symptoms (Box 3.1).

It is clear that patients with nasal symptoms can have other sources for their symptoms than purely inflammation. Lund et al have recently suggested a classification of rhinitis into four types: structural; infectious; allergic; and “other.”1 This system recognizes that anatomic and infectious factors may also play a role in the expression of symptoms among patients. Structural rhinitis, for example, involves the presence of anatomic abnormalities such as deviation of the nasal septum and hypertrophy of the inferior turbinates that can interfere with air flow through the nose. Infectious rhinitis includes both acute and chronic rhinosinusitis, which have significant impact on nasal inflammation and nasal symptoms. In fact, current classification schemes do not differentiate infectious rhinitis from infectious rhinosinusitis, recognizing the key role that nasal disease plays in the sinus pathology among these patients. The remaining two categories in the system devised by Lund et al, allergic rhinitis and “other” rhinitis, correspond to the categories of allergic and nonallergic rhinitis discussed above. While nasal obstruction due to anatomic deformity or variability can be important, surgical management of these conditions is beyond the scope of the present textbook. The management of patients with acute and chronic rhinosinusitis is presented in Chapter 4.

▪ Allergic Rhinitis

The term allergic rhinitis (AR) refers to a condition manifested by nasal inflammation, and triggered by an immunologic response of the nasal and sinus mucosa. This immunologic response is primarily mediated by immunoglobulin E (IgE), and expressed through the influence of a number of humoral and cellular mediators. AR has traditionally been divided into two categories based upon the temporal course of the development and presentations of the symptoms: seasonal allergic rhinitis (SAR), which refers to immune-mediated nasal symptoms triggered by seasonal increases in environmental antigens, such as tree, grass and weed pollens and outdoor molds; and perennial allergic rhinitis (PAR), which refers to nasal symptoms occurring throughout the year, and generally attributed to indoor antigens such as animal dander, dust mites, cockroach, and indoor molds.2

Seasonal Allergic Rhinitis (SAR)

In most parts of the developed world, there are three distinct times of the year in which patients with SAR may become symptomatic. These three times of symptom expression correspond to the periods at which various plant families pollinate, and can broadly be correlated with the spring, summer, and fall seasons. As a general rule, in more temperate climates these pollen seasons are relatively distinct, with tree pollen commonly present in the spring, grass pollen in the summer, and weed pollen in the fall. In addition, mold spores are often present in warmer weather, and can be present for much of the year in warmer and more humid climates.

ARIA Classification of Allergic Rhinitis

While most of the literature on the diagnosis and treatment of allergic rhinitis has utilized this dichotomous classification based on seasonality of symptoms, expert opinion has recently suggested a new system for the classification of AR. This approach, which is based upon the chronicity and severity of symptoms of AR, was presented through a report entitled the ARIA Guidelines (Allergic Rhinitis and Its Impact on Asthma).3 The ARIA report suggests that a similar system should be used for the classification of allergic rhinitis to that used in classifying asthma.

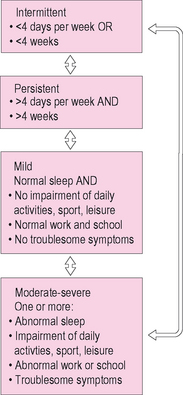

The ARIA approach has four diagnostic categories that are used to classify the severity and chronicity of symptoms: (1) mild intermittent AR; (2) moderate-severe intermittent AR; (3) mild persistent AR; and (4) moderate-severe persistent AR (Figure 3.1). In this system, chronicity is divided into two categories: intermittent and persistent. Intermittent AR is defined as a symptomatic period lasting less than 4 days a week or less than 4 weeks a year. Persistent AR is defined as symptomatic periods lasting more than 4 days a week and occurring more than 4 weeks a year. In classifying the severity of rhinitis, the ARIA system defines two levels based upon the clinician’s assessment of the impact of rhinitis symptoms on daily function, sleep, or quality of life. Mild disease is characterized by symptoms that are bothersome to the patient, but do not cause significant impact on sleep, daily function, or quality of life. Moderate-severe disease differs from mild disease, in that it is characterized by symptoms that interfere with daytime function, adversely impact sleep quality or duration, or cause a decrease in global or disease-specific quality of life. Based upon an evaluation of severity and chronicity, the ARIA guidelines suggest a pattern of pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions.

▪ Nonallergic Rhinitis

Nonallergic rhinitis, in contrast to allergic rhinitis, refers to nonimmune-mediated nasal inflammation or irritation that promotes nasal symptoms such as congestion and rhinorrhea. Nonallergic rhinitis is a syndrome that cannot be explained by any uniform or consistent pathophysiologic mechanism. This condition involves many differing physiologic processes, and is often considered a “diagnosis of exclusion” among patients with nasal symptoms. Various triggers for the expression of nonallergic symptoms in the nose include infection, hormonal variability, pharmacologic agents, and autonomic dysregulation.4

Bachert recently divided nonallergic rhinitis into five categories based on their underlying etiology. He described these five categories as: (1) irritative-toxic (occupational) rhinitis; (2) hormonal rhinitis; (3) drug-induced rhinitis; (4) idiopathic (vasomotor) rhinitis; and (5) other forms (e.g., nonallergic rhinitis with eosinophilia (NARES)).5 Bachert provided specific information regarding the mechanisms and triggers for these various types of nonallergic rhinitis.

Drug-induced Rhinitis

Bachert notes that many medications can affect nasal physiology. Many classes of medications, including angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, beta-blockers and other antihypertensive agents, oral contraceptives, psychotropic medications, topical nasal decongestants, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medications, and phospodiasterase type-5 inhibitors (PDE-5) have been shown to have effects on the nose (Box 3.2).

Nonallergic Rhinitis with Eosinophilia (NARES)

Patients with NARES present with paroxysmal sneezing episodes, profuse watery rhinorrhea, nasal pruritis, nasal congestion, and hyposmia/anosmia. In contrast to allergic rhinitis patients, however, these patients fail to demonstrate any evidence for allergy on testing, yet have numerous eosinophils on nasal smears.6 Although its etiology is unknown, NARES shares clinical characteristics with Samter’s triad (aspirin sensitivity, asthma, and nasal polyposis), and may reflect a variant of that disease.

Epidemiology and Burden of Rhinitis

Overview

As noted above, rhinitis can be defined as an inflammatory or irritative disorder of the nasal membranes. Rhinitis presents with a pattern of symptoms that usually includes sneezing, nasal itching, rhinorrhea, and nasal congestion.7 In addition, patients with rhinitis will often complain of changes in the sense of smell, facial pressure or fullness, headache, and aural blockage. During periods of increased symptoms, patient with rhinitis experience a significant impact on both function and quality of life.

While nasal symptoms of rhinitis can be bothersome to patients and significantly interfere with normal function, the comorbidities of rhinitis can be quite serious and even life-threatening. Rhinitis represents inflammation in one part of the respiratory system, and can be associated with other common and serious respiratory illnesses such as rhinosinusitis and asthma.8 In fact, among patients with asthma, the prevalence of rhinitis in that population approaches 90%.9 In addition, rhinitis appears to play a role in the severity of symptoms among individuals with obstructive sleep apnea.10 Furthermore, the treatment of patients with chronic rhinosinusitis is often less successful among patients with allergic rhinitis than it is among their nonallergic counterparts. Because of its functional impairment and its serious comorbidities, rhinitis is therefore not a trivial disease, but one that can have serious medical and functional consequences.

Burden of rhinitis

The economic impact of rhinitis is significant. Direct costs annually attributable to the treatment of allergic rhinitis alone were estimated in 2003 to range between US$2 and 5 billion.11 In addition, the indirect costs of AR significantly contribute to the economic burden of the disease, with an estimated US$5–10 billion annually attributable to the morbidity of this common disease.11 In another recent estimate, over US$6 billion was outlayed specifically for prescription medications used for treating the symptoms of allergic rhinitis.12 Worldwide treatment of rhinitis would certainly account for a significant increment in these US figures.

In addition to the direct and indirect financial costs of allergic and nonallergic rhinitis, quality of life, daytime function, and sleep are frequently compromised among patients, not only by the disease states but also by treatments whose adverse effects further adversely impact function. Patients with allergic and nonallergic rhinitis experience a wide range of cognitive and social issues that can be disruptive in their daily activities and interpersonal relationships. Fatigue, confusion, distractibility and other cognitive symptoms are common among patients with rhinitis, and can be worsened by treatment with pharmacologic agents such as sedating antihistamines. Among children with allergic rhinitis similar effects can be seen, resulting in decrements in learning and attention in the classroom.13 In addition, patients with AR experience disruption in normal patterns of sleep, which can contribute to daytime symptoms.14

Prevalence of Rhinitis

Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis are common illnesses. Prevalence studies worldwide suggest that the rates of AR within the population vary between 10% and 20%.15,16 It has been reported that 58 million Americans annually experience symptoms of allergic rhinitis, while 19 million Americans experience symptoms of nonallergic rhinitis.15 As was noted earlier, many patients have both nonallergic and allergic triggers for their symptoms. This mixed rhinitis can occur in up to 44% of patients with AR.15

In addition to these absolute values, there is evidence that the prevalence of AR is increasing. Several studies have shown that the rates of AR have increased at least twofold over the past two decades.17,18 While several hypotheses have been suggested to explain this increasing prevalence, the reasons for this steady increase remain speculative.

Managing the Patient with Allergic Rhinitis

▪ Pathophysiology

Allergic rhinitis is an immune-mediated inflammatory condition that affects the mucosa of the nose, paranasal sinuses, and related mucosal structures. The primary mechanism underlying AR involves a type-I hypersensitivity reaction that is directed by various cellular and humoral agents. It is mediated through processes under the control of T-helper 2 cells, and involves a complex interaction of various inflammatory mechanisms. A full review of the immunology of the allergic response is presented in Chapter 1.

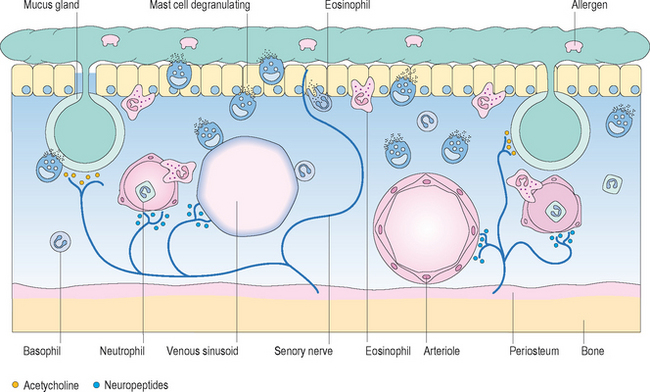

The allergic response in the nose is initiated when individuals come into contact with antigens to which they have been previously sensitized. IgE molecules that had been synthesized during the sensitization process to these antigens are present on the surface of mast cells, and have specific determinants available to bind to these antigens. When antigen particles bind to adjacent IgE molecules, a sequence of biochemical events occurs, resulting in degranulation of mast cells and release of preformed mediators such as histamine into the nasal tissues. This process of degranulation and histamine release is the primary process responsible for initiation of the immediate allergic response.19

Histamine binds to specific histamine-1 (H1) receptors on the surface of target cells in the nose, leading to local effects in the nasal mucosa, including transudation of plasma, engorgement and edema of the mucosa, stimulation of mucous glands to produce increased mucus secretions, and other direct inflammatory events.20 In addition, histamine, as well as other mediators and neuropeptides released during the allergic response, cause stimulation of fine sensory nerves in the nasal mucosa, resulting in irritative effects such as sneezing and itching (Figure 3.2).2 These events occur rapidly after exposure to a sensitized antigen, often leading to the development of symptoms within 5–10 minutes of contact. Symptoms of allergic rhinitis, such as sneezing, itching, rhinorrhea, and nasal congestion, occur as a result of these inflammatory processes that occur after exposure, and characterize the “early-phase” response to allergic stimulation.

Figure 3.2 Acute-phase mucosal response to antigen.

(Reproduced with permission from Holgate ST. Allergy, 2nd edn, figure 4.9, p. 59, published by Mosby, 2001.)

In addition to these immediate effects that occur rapidly after exposure, a second, delayed process of inflammation occurs in many patients with AR. This delayed expression of nasal symptoms is referred to as the “late-phase” response, and results in expression of symptoms at 2–4 hours after exposure or more. While the early phase response occurs primarily as a response to histamine, the late phase response is directed by other mediators such as cysteinyl leukotrienes and inflammatory cells such as eosinophils and basophils.2 An appreciation of this biphasic response in AR is important in understanding the method of presentation among patients with AR and various treatment options specific for these inflammatory processes.

▪ Presentation

While allergic rhinitis can develop at any age, the majority of patients with allergic rhinitis first present with symptoms in middle childhood. Recent prevalence data suggest that up to 40% of children may express symptoms of AR in early childhood.21 Other studies suggest that the mean age for diagnosis of allergic rhinitis is between the ages of 9 and 11 years.16 Symptoms tend to be experienced most significantly among patients between 10 and 40 years of age, and decline somewhat thereafter. It is uncommon for patients under age 2 to experience symptoms related to allergic rhinitis. In addition, while patients may first express symptoms of allergic rhinitis in their older years, the onset of rhinitis symptoms among patients older than 55 years of age would strongly favor a diagnosis of nonallergic rhinitis.

In addition, due to the significant mucosal inflammation of the nasal and sinus membranes, and due to their concurrent nasal obstruction and congestion, many patients with both AR will report a decreased sense of smell or taste, facial pressure or pain, and temporal or frontal headache.22 These symptoms of pressure and anosmia are also common among patients with chronic sinonasal polyposis and acute and chronic rhinosinusitis.

In patients with SAR, the waxing and waning of symptoms follows the pollen counts during those seasons in which the patient has allergic sensitization to the pollens present in the environment. These symptoms will usually lag for a few days following the seasonal pollen fluctuations, and can be blunted by the use of various medications. This seasonal change in patient symptoms offers an important element of the clinical history that can be used by the clinician in confirming a diagnosis of allergic rhinitis. Seasonal changes in chronically stable symptoms among patients with PAR also suggest a seasonal component to the patient’s PAR.

In those patients with PAR, symptoms are generally present throughout all seasons of the year. The diagnosis of PAR based on history alone can often be more difficult than that of SAR due to the absence of a clear seasonality to the patient’s symptoms. In addition, patients with PAR often experience a somewhat different cluster of symptoms than those noted by the patient with SAR. Among patients with PAR, nasal obstruction and postnasal drainage appear more commonly than the sneezing and itching often seen more frequently among patients with SAR.22 In addition, since both chronic rhinosinusitis and nonallergic rhinitis can have similar symptom patterns to PAR, it can be difficult to diagnose PAR without confirmatory testing.

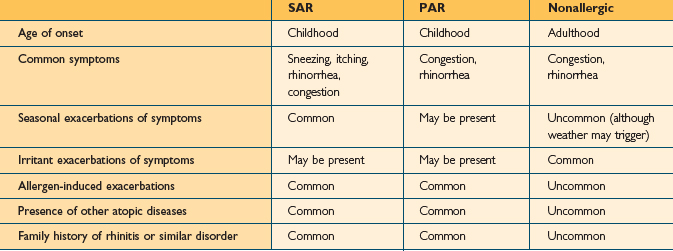

While AR and nonallergic rhinitis both present with symptoms related to nasal inflammation and irritation, the pattern of symptoms is usually different in the two conditions. The type of symptoms noted in patients with nonallergic rhinitis depends on the pathophysiological processes involved and the mechanisms of nasal irritation or inflammation. For example, patients with vasomotor rhinitis present predominantly with clear rhinorrhea, while those with rhinitis of pregnancy present with congestion. The presentation of patients with nonallergic rhinitis will be discussed later. Table 3.1 displays some common differences between the presentations of patients with AR and nonallergic rhinitis.

▪ Diagnosis

History

The evaluation of the patient with symptoms of rhinitis in large part depends on a thorough and careful history. Patients with both allergic and nonallergic rhinitis will present with characteristic symptoms that can be elicited through the history. In addition, the patient’s history can often distinguish AR from nonallergic rhinitis (Table 3.1).

While not all patients with AR complain of seasonal triggers or fluctuations related to time of the year, seasonal variability of the patient’s nasal symptoms is also important to assess. The symptoms of SAR demonstrate a clear relationship with the increase of pollen in the environment during discrete seasons of the year. This variability of symptoms is an important component of the history among patients with rhinitis, and suggests a diagnosis of SAR. Patients with PAR may also have a seasonal worsening of symptoms, but will have significant symptoms between traditional pollen seasons. Many patients with AR will present with complaints characteristic of both SAR and PAR.

Physical Examination

The physical examination of the patient with symptoms of rhinitis involves not only a careful evaluation of the nose itself, but also a comprehensive evaluation of the head, neck, and chest as well. The physical examination begins with an inspection of the face. The clinician will examine the face for external signs suggesting nasal inflammation. These signs include facial puffiness, edema, facial asymmetry, or infraorbital discoloration (Figure 3.3). The eyes are examined for evidence of conjunctival injection, irritation or erythema. Infraorbital darkening of the skin implies venous stasis due to nasal congestion. Allergic patients often demonstrate fine creases in the eyelids, noted as Dennie’s lines. These fine creases occur due to spasms of Mueller’s muscles, and are often seen in children with AR.

Figure 3.3 Facial appearance of a child with rhinitis.

(Reproduced with permission from Zitelli BJ. Atlas of pediatric physical diagnosis, 3rd edn, published by Mosby, 1997.)

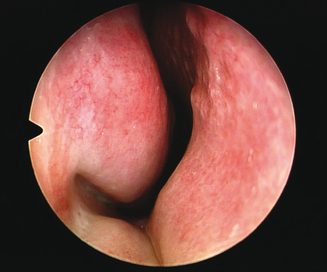

The clinician then examines the interior structure of the nose. The anterior portion of the nasal septum is inspected for asymmetry, spurring, or presence or excoriation or perforation. The clinician notes any signs of deformity that may interfere with nasal airflow. In addition, the clinician again notes any sign of collapse of the lateral nasal soft tissues and assesses the degree of concurrent nasal obstruction. Finally the clinician assesses the size of the inferior turbinates, and estimates the degree to which they obstruct nasal airflow (Figure 3.4). It is very important for the clinician to also instill a small amount of a nasal decongestant such as oxymetazoline into the nose bilaterally to assess the reduction in the size and bulk of the turbinates after administration. A significant amount of reversibility will predict a good response to nasal medications in treating this airway obstruction.

Finally, since asthma can be present in up to 40% of patients with AR,9 the clinician examines the chest with auscultation. While in many patients with asthma the chest examination may be unremarkable, in patients with significant disease or those undergoing an acute exacerbation of asthma, examination of the chest with both normal and forced expiration may demonstrate end-expiratory wheezing. In cases where asthma is suspected on the basis of history, pulmonary function testing may be useful in securing a diagnosis.

Allergy Testing

In many patients with rhinitis, it can be difficult from history and physical examination alone to determine whether the rhinitis symptoms are related to allergy or are a manifestation of nonallergic rhinitis. In these cases, testing can be performed to clarify the diagnosis. In addition, allergy testing can be performed to aid with environmental control, or if the clinician plans to implement immunotherapy as part of the comprehensive treatment of the patient with AR. Several methods of allergy testing have been developed and are used in clinical practice around the world. Both in vivo and in vitro techniques are available for the testing of allergic sensitivities in adults and children, and offer complementary qualities that can be used in the evaluation of specific patients. Rapid screens can be used to identify the presence or absence of allergic sensitivities, while more comprehensive testing can be used for treatment planning in those patients who are allergic.23

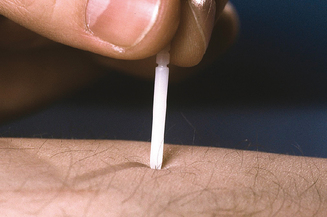

The most common methods used for assessment of the patient with suspected AR involve skin testing. The skin is chosen as the most common site for testing since it is readily available, easily examined, and contains a mast cell population that reacts to the presence of antigen in a similar manner to the nasal mucosa. Skin testing can be performed using epicutaneous methods, as in prick/puncture testing, or using percutaneous techniques, as with intradermal testing.24 The allergens that are used for testing are chosen on the basis of the common seasonal and perennial antigens present in the geographic locale of the patient being tested.

The most commonly employed skin tests used in both the USA and internationally for the assessment of allergy are prick tests (Figure 3.5). In prick testing, the nurse or technician introduces a small volume of each antigen to be tested into the superficial epidermis. Various devices and methods have been developed to perform these tests. When an allergic patient is exposed to an antigen on the skin to which that patient has been previously sensitized, the area into which the antigen is introduced will develop erythema and induration around the site of introduction. When used in the context of proper controls, this reaction implies the presence of an antigen-specific immune response. The presence of a reaction is recorded for each antigen tested. This reaction can simply be noted as positive or negative, or can be graded or measured. The size of the reaction can be used to estimate in a semiquantitative manner the strength of the allergic response.24

Intradermal testing can also be used for the assessment of allergic sensitivity. Intradermal tests can be employed as single-strength challenges following negative prick testing, or can be utilized in a sequential manner as in intradermal dilutional testing (IDT).24 In intradermal testing, the nurse or technician injects a small amount of antigen into the superficial dermis in order to raise a wheal of discrete size, often 4 mm. As described with prick testing, if the patient is sensitive to the specific allergen being tested, an increase in the size of the wheal to 7 mm will be seen.

Techniques have been developed to employ a blend of prick and intradermal techniques in order to estimate quantitatively the degree of allergic sensitivity for specific antigens. One such technique, modified quantitative testing (MQT), has been used increasingly, and has shown good sensitivity, specificity, and utility.24–26

In contrast to skin testing, in vitro tests can be used to assess the presence or absence of allergic sensitivity. While total IgE level has been suggested as a marker for assessing the presence of allergy, its use is of questionable utility.27 The assessment of IgE levels to specific antigens, however, allows a quantitative assessment of the strength of the allergic response. These specific IgE tests, often generically referred to as “RAST tests” (radioallergosorbent testing), involve the laboratory assessment of levels of IgE antibody specific to each antigen being tested. The amount of specific IgE can be measured for each antigen, and has been shown to correlate well with the degree of responsiveness on the skin.28

▪ Treatment

Environmental Control Measures

In patients with AR, a systematic approach focused on decreasing exposure to offending antigens can be effective in decreasing the level of patient symptoms. Avoidance of antigens that are known to trigger an exacerbation of disease can reduce the total antigenic burden, and can lead to improved outcomes with fewer symptoms and improved disease-specific quality of life. Environmental control strategies are conceptually straightforward, although they can be difficult to implement successfully. While patients can often be successful in avoiding or decreasing exposure to perennial antigens such as cat dander, it may be more difficult to limit exposure to widespread environmental antigens such as pollen.29 Despite the relative difficulty in applying these principles, the successful integration of environment control strategies can be useful in decreasing patient symptoms.

There have been several studies that have looked at reducing exposure to perennial antigens such as dust mite and cat dander. In one recent study, young children who implemented strict methods at reducing dust mite exposure were less likely to become sensitized to this antigen than those who did not practice such techniques.30 Measures often recommended to reduce exposure to dust mite antigen include the use of allergen-impermeable covers for mattresses and pillows. In addition, the use of effective air filters, such as high-efficiency filtration (HEPA filters), can also be of benefit. In more extreme cases the removal of carpeting and curtains can be useful, although this strategy is expensive and of questionable benefit.31 Methods that can be effective at reducing indoor levels of mold antigen involve keeping the home at a low humidity level and the removal of indoor plants.

Pharmacotherapy

Antihistamines

Antihistamines were first developed in the 1930s and 1940s, although they did not come into widespread use until the 1950s, when many of the toxic effects of the original compounds were eliminated. The initial antihistamines in common clinical use, including diphenhydramine, chlorpheniramine, and tripolidine, were noted to have clinical effect in reducing symptoms of AR, yet were accompanied by significant adverse effects such as sedation and somnolence. These early antihistamines, also described as “first-generation” antihistamines, demonstrated significant lipophilicity and can be demonstrated to freely cross the blood–brain barrier and affect central histamine receptors.32 These agents therefore had direct effect on central H1 receptors, resulting in significant sedation, impaired cognition, and decreased psychomotor function. These agents also demonstrated poor receptor selectivity, binding to both cholinergic and muscarinic receptors. This poor selectivity is responsible for side effects such as cognitive slowing, dry mouth, blurred vision, and increased thickness of mucus.

The major role for antihistamines in the management of the patient with AR is in relieving the irritative symptoms of allergic rhinitis, especially the sneezing and itching that are commonly associated with SAR. In general, antihistamines demonstrate better efficacy with SAR than they do with PAR. In addition, antihistamines demonstrate some effect on reducing rhinorrhea, although the newer agents are less effective than the first-generation antihistamines due to the anticholinergic properties of the latter. Antihistamines have little effect on nasal obstruction, however, and are therefore not appropriate monotherapy for the patient in whom nasal congestion or stuffiness is a major symptom. In these patients, antihistamines are frequently used concurrently with medications from other classes when nasal congestion is a primary symptom of AR. A major class of medications includes dual antihistamine/decongestant products, used to treat both the irritative and obstructive symptoms of rhinitis. Antihistamines do not have benefit in the management of patients with nonallergic rhinitis. Since nonallergic rhinitis is not mediated through histamine release from mast cells, antihistamines do not have clinical effect among these patients.

While older antihistamines such as diphenhydramine continue to be available in pharmacies, current treatment guidelines for AR recommend against the use of these sedating antihistamines.33 These agents offer no advantage in potency or treatment efficacy over the safer current medications. In those unusual circumstances in which clinicians do recommend a sedating antihistamine is preferential, they should advise their patients about the risk for significant sedation and cognitive and psychomotor impairment, and should note the reason for recommending this medication and the subsequent discussion with the patient in the medical record.

Decongestants

In addition to topical decongestant medications, oral decongestants are also used commonly for nasal obstruction. The medication that has traditionally had the most widespread use is pseudoephedrine, although the ease with which it can be used to synthesize methamphetamine has restricted its availability. An alternate medication, phenylephrine, is being more widely recommended as an oral decongestant since it cannot be used for synthesis of methamphetamine. It appears to have lesser clinical efficacy than pseudoephedrine, however, in the treatment of nasal congestion. Another oral decongestant, phenylpropanolamine (PPA), was removed from the market in the USA in 2003 when it was shown to have an epidemiological association with an increased risk of hemorrhagic stroke among young women using the medication as a diet aid.34

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids are highly effective in the treatment of AR, and have a role in both the management of acute exacerbations of AR as well as in the control of chronic AR. Corticosteroids can be used systemically or topically in patients with AR. While parenteral use of corticosteroids has been used frequently in the past, it is not recommended under current guidelines due to increased risk of systemic side effects when compared with oral corticosteroids.7 Oral corticosteroids such as prednisone and methylprednisolone are appropriate for the management of severe AR, and can be used for short periods of time with little risk. Oral corticosteroids are also of benefit in treating patient with AR who have exacerbations of chronic rhinosinusitis or asthma.

Topical intranasal corticosteroids are being used increasingly for the treatment of AR. Comparative studies have shown these agents to be more efficacious then antihistamines in the management of patients with AR.35 Safety studies have demonstrated the topical intranasal corticosteroids to be safe and well tolerated.36 These medications have been shown to have only limited side effects both in the nose and systemically, and newer agents such as mometasone furoate and fluticasone propionate have been demonstrated in year-long prospective studies to be free of growth suppression over one year of use in children. They also have demonstrated lower systemic absorptions and decreased systemic bioavailability and to be free of suppression of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. These topical intranasal corticosteroids would therefore be predicted to be less likely to provoke systemic effects than agents with higher systemic absorptions.

Leukotriene modifiers

Leukotriene receptor antagonists (LTRA) have shown benefit in the treatment of both SAR and PAR. Both montelukast and zafirlukast have been shown to have benefit in the treatment of the symptoms of AR, although the only approved LTRA for the treatment of AR in the USA is montelukast. Montelukast does display efficacy in the treatment of both SAR and PAR, and relieves both nasal and non-nasal symptoms among these patients. Several studies have demonstrated that montelukast has similar efficacy in the treatment of SAR to antihistamines such as loratadine.37,38

Anti-IgE

Since the allergic response is initiated by antigen binding to IgE antibody molecules on the surface of mast cells, theoretically an agent that reduces the amount of IgE bound to these cells would be expected to decrease degranulation and histamine release. One medication that has been shown to decrease IgE in this manner, omalizumab, is available for the treatment of refractory asthma among patients with elevated serum levels of total IgE. This medication, which is administered parenterally, decreases the amount of serum IgE, resulting in decreased mast cell-bound IgE and a blunting of the allergic response. Omalizumab has shown good efficacy in the treatment of severe asthma, decreasing the number of exacerbations on an annual basis. Preliminary studies have also demonstrated efficacy in AR,39 although its practical use in AR is limited by its high cost. Future applications of monoclonal anti-IgE molecules in AR will likely be developed, but at present it is not a recommended treatment for rhinitis.

Rational Pharmacotherapeutic Management of Allergic Rhinitis

As noted earlier, patients with AR have a chronic disease that will cause them to have symptoms for a significant number of years. In patients with mild SAR, intermittent use of medications during the seasons in which the individual is symptomatic would appear to be a practical and efficacious approach to therapy. In patients with irritative symptoms of SAR, oral antihistamines offer good relief and newer agents can be used safely and without adverse effects throughout the season. Short-term use of oral decongestants can be used for obstructive symptoms in these SAR patients as well. More refractory or prolonged congestion can successfully be managed using topical intranasal corticosteroids, or even a brief course of oral corticosteroid medications.

Summary

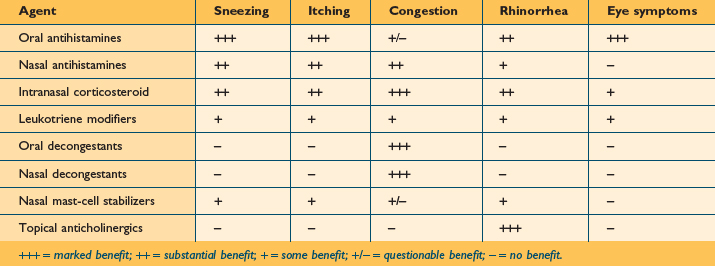

As noted, pharmacotherapy remains the mainstay in the treatment of patients with AR. There are a variety of topical and systemic medications available for treating AR, and new medications and treatment approaches will likely be noted over the coming decade. Table 3.2 provides a summary of the currently available classes of medications used for treating the symptoms of both AR and nonallergic rhinitis, and offers an estimate of the relative efficacy of each of these classes in the treatment of the various nasal and non-nasal symptoms associated with these diseases.

Immunotherapy

In traditional SC immunotherapy, very low concentrations of antigen are injected subcutaneously over a period of 3–5 years. The concentration of antigen is steadily increased over the period of several months until the patient is receiving a maximally tolerated concentration of each antigen to which the patient is allergic. This concentration is then held stable as the patient continues SC injections weekly, biweekly, or monthly over several years. While SC immunotherapy can rarely be accompanied with local or systemic adverse reactions, which at times can be serious, the safety of SC immunotherapy in treating AR has been well established.40

A large experience from the European allergy community suggests that immunotherapy can also be safely and effectively delivered through the SL route. Several large-scale placebo-controlled studies have demonstrated the efficacy of SL immunotherapy for the treatment of AR.41,42 In addition, SL immunotherapy does not appear to be associated with the risk of anaphylaxis, as can be seen with SC immunotherapy. Mild local and systemic reactions have been noted, but are generally not sufficient to discontinue treatment. The SL route of administering immunotherapy will likely become more common and mainstream within the USA over the next decade.

While the precise mechanisms through which immunotherapy is able to decrease allergic responsiveness are not fully understood, it is felt that immunotherapy decreases T-cell responsiveness, stimulates a shift from T-helper 1 to T-helper 2 populations, and decreases antibody responsiveness through decreasing specific IgE and increasing specific IgG4 levels with treatment.43 The onset of action with immunotherapy is generally seen within 3–6 months after the initiation of treatment. In order to stimulate persistent immune change, treatment for at least 3–5 years is suggested.

Guidelines-based Therapy

As can be seen through the above discussion, there are numerous treatment options available for the management of the patient with AR. While clinicians will generally select various treatment options based on their experience and familiarity, consistent approaches to the selection of therapies for AR based on evidence can improve patient outcomes. A recent study by Bousquet and colleagues suggested that adherence to guidelines-based recommendations in the treatment of AR can lead to more effective treatment and improved quality of life.44

Several guidelines have been developed over the past two decades that can be used to effectively treat patients with AR. In 1998, the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters reported that intranasal corticosteroids are the most effective class of treatment for the symptoms of AR. This committee also reported that nonsedating antihistamines should be utilized as appropriate first-line therapy for patients in which the irritative symptoms of AR are primary. When nasal congestion was present to a significant degree, the committee reported that either an oral decongestant or an intranasal steroid could be used as a complementary or alternative therapy.7 Similar guidelines were reported by the European Academy of Allergology and Clinical Immunology (EAACI).

In 2001, the World Health Organization (WHO) impaneled an international committee of allergy specialists to examine current treatment options for patients with AR. The guidelines that were developed as a result of the deliberations of this panel are published as the ARIA Guidelines.3 ARIA is an acronym for “Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma,” and describes treatment guidelines for AR that parallel those used in the treatment of asthma. The conceptual framework for the ARIA guidelines is based on the model of the upper and lower airways as an integrated unit. ARIA argues that allergic rhinitis represents an inflammatory disease of the upper airway, just as asthma represents an inflammatory disease of the lower airway. The classification of AR follows similar rules to that used with the classification of asthma, and the treatment for AR also follows similar guidelines.

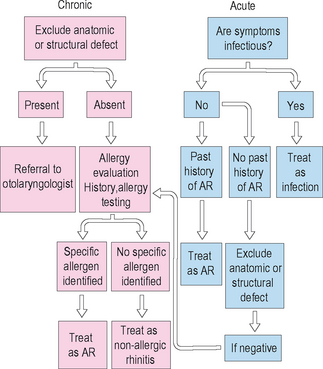

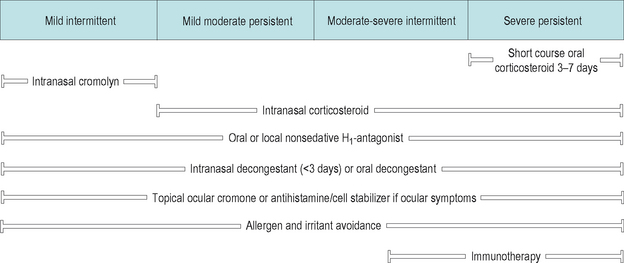

The ARIA guidelines depart from the traditional scheme of classifying AR into seasonal AR and perennial AR. They present a model in which AR is divided into four distinct categories based upon the severity and chronicity of the disease. The ARIA guidelines then recommend a stepped care approach to therapy based upon the classification of patient symptoms (Figure 3.6).

Figure 3.6 ARIA treatment guidelines for allergic rhinitis.

(Reproduced with permission from Bousquet J, et al. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108 (5 suppl):S147–S334.)

Three treatment patterns can be seen in the ARIA guidelines.

All patients should have education concerning their AR and management of environmental exposures. In patients with severe disease oral corticosteroids can be utilized for treatment of severe symptoms or exacerbations. In addition, immunotherapy is recommended in patients with significant persistent disease to decrease allergic sensitization (Figure 3.6).

Managing the Patient with Nonallergic Rhinitis

▪ Presentation

While the patient with allergic rhinitis usually displays classic symptoms that strongly suggest the diagnosis of SAR or PAR, the symptom pattern among patients with nonallergic rhinitis can be much less specific, more variable, and more difficult to classify. Again, while classic symptoms of rhinitis such as sneezing, itching, congestion, and rhinorrhea are seen in both AR and nonallergic rhinitis, irritative symptoms such as sneezing and itching are generally uncommon among nonallergic patients, except among those patients with NARES syndrome. The symptom pattern among patients with nonallergic rhinitis usually is characterized by nasal congestion, anterior or posterior nasal rhinorrhea, or both.

▪ Diagnosis

History

In evaluating the patient with rhinitis, a thorough medical history is essential. The patient’s current list of prescription and over-the-counter medications must be evaluated for any agents that might be causing a drug-induced rhinitis. Agents such as antihypertensives, beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, contraceptives, and erectile dysfunction medications are of particular interest. In addition, the patient’s use of herbal medications and alcohol must be evaluated. Patients often fail to consider over-the-counter medications and herbal preparations as true medications, so the clinician must be diligent in pursuing the use of these agents. Finally, the use of topical nasal decongestants is a frequent trigger for chronic nasal congestion, and the patient must be specifically asked about use of this class of medications.

▪ Treatment

Overview

In contrast to the treatment of patients with AR, no specific evidence-based guidelines have been developed to treat patients with nonallergic rhinitis. In addition, treatment can be somewhat more challenging and less effective than the treatment of AR. For that reason flexibility and the use of complementary treatment strategies are necessary elements of the treatment of patients with nonallergic rhinitis.

Pharmacotherapy

Corticosteroids

Oral corticosteroids can also be effective in the treatment of NARES. In these patients, oral treatment can often be used to initiate therapy and promote a reduction in the prominent nasal mucosal edema. Reduction in edema is essential in allowing topical medical therapies to access the mucosa and allow efficacy.

Conclusions

Figure 3.7 illustrates an algorithm for distinguishing allergic and nonallergic rhinitis clinically. Application of similar algorithms can be important to assist the clinician in reaching the most appropriate diagnosis and instituting efficacious therapy. It is critical that clinicians arrive at the correct diagnosis in the patient with rhinitis so that the most effective method of treatment can be selected for that patient.

1 Lund VJ, Aaronson A, Bousquet J, et al. International Consensus Report on the diagnosis and management of rhinitis. Allergy. 1994;19:5-34.

2 Baroody FM. Allergic rhinitis: broader disease effects and implications for management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;128:616-631.

3 Bousquet J, Van Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev N, ARIA Workshop Group, World Health Organization. Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108:S147-S334.

4 Scadding GK. Nonallergic rhinitis: diagnosis and management. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;1:15-20.

5 Bachert C. Persistent rhinitis – allergic or nonallergic? Allergy. 2004;59(suppl 76):11-15.

6 Mullarkey MF, Hill JS, Webb DR. Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis: their characterization with attention to the meaning of nasal eosinophilia. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1980;65:122-126.

7 Dykewicz MS, Fineman S, Skoner DP, et al. Diagnosis and management of rhinitis. Complete guidelines of the Joint Task Force on Practice Parameters in Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 1998;81:478-518.

8 Meltzer EO, Szwarcberg J, Pill MW. Allergic rhinitis, asthma, and rhinosinusitis: diseases of the integrated airway. J Manag Care Pharm. 2004;10:310-317.

9 Corren J. Allergic rhinitis and asthma: how important is the link? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1997;99:S781-S786.

10 Staevska MT, Mandajieva MA, Dimitrov VD. Rhinitis and sleep apnea. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2004;4:193-199.

11 Reed SD, Lee TA, McCrory DC. The economic burden of allergic rhinitis: a critical evaluation of the literature. Pharmacoeconomics. 2004;22:345-361.

12 Stempel DA, Woolf R. The cost of treating allergic rhinitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2002;2:223-230.

13 Juniper EF, Rorhbaugh T, Meltzer EO. A questionnaire to measure quality of life in adults with nocturnal allergic rhinoconjunctivitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:484-490.

14 Krouse HJ, Davis JE, Krouse JH. Immune mediators in allergic rhinitis and sleep. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2002;126:607-613.

15 Settipane RA. Demographics and epidemiology of allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2001;22:185-189.

16 Naclerio R, Solomon W. Rhinitis and inhalant allergens. JAMA. 1997;278:1842-1848.

17 Rusznak C, Davalia JL, Davies RJ. The impact of pollution on allergic disease. Allergy. 1994;49:21-27.

18 Davies RJ, Rusznak C, Devalia JL. Why is allergy increasing? – environmental factors. Clin Exp Allergy. 1998;28(suppl 6):8-14.

19 Gomez E, Corrado OH, Baldwin DL, et al. Direct in vivo evidence for mast cell degranulation during allergen-induced reactions in man. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1986;78:637-645.

20 Naclerio RM. Allergic rhinitis. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:860-869.

21 Wright AL. The epidemiology of the atopic child: who is at risk for what? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;113:S2-S7.

22 Krouse JH. Seasonal and perennial rhinitis. In Krouse JH, Chadwick SJ, Gordon BR, et al, eds. Allergy and immunology: an otolaryngic approach. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2002.

23 Krouse JH, Stachler RJ, Shah A. Current in vivo and in vitro screens for inhalant allergy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2003;36:855-868.

24 Krouse JH, Mabry RL. Skin testing for inhalant allergy 2003: current strategies. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:S33-S49.

25 Krouse JH, Krouse HJ. Modulation of immune mediators with MQT-based immunotherapy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:746-750.

26 Peltier J, Ryan MW. Comparison of intradermal dilutional testing with the Multi-Test II applicator in testing for mold allergy. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;134:240-244.

27 Salkie ML. Role of clinical laboratory in allergy testing. Clin Biochem. 1994;27:343-355.

28 Fadal RG. Experience with RAST-based immunotherapy. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1992;25:43-60.

29 Scadding GK, Church MK. Rhinitis. In Holgate ST, Church MK, Lichtenstein LM, editors: Allergy, 2nd edn., London: Mosby, 2001.

30 Arshad SH, Bateman B, Matthews SM. Primary prevention of asthma and atopy during childhood by allergen avoidance in infancy: a randomized controlled study. Thorax. 2003;58:489-493.

31 Terreehorst I, Hak E, Oosting AJ, et al. Evaluation of impermeable covers for bedding in patients with allergic rhinitis. N Engl J Med. 2003;17:237-246.

32 Tashino M, Sakurada Y, Iwabuchi K, et al. Central effects of fexofenadine and cetirizine: measurement of psychomotor performance, subjective sleepiness, and brain histamine H1-receptor occupancy using 11C-doxepin positron emission tomography. J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;44:890-900.

33 Casale TB, Blaiss MS, Gelfand E, et al. First do no harm: managing antihistamine impairment in patients with allergic rhinitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2003;111:S835-S842.

34 Kernan WN, Viscoli CM, Brass LM, et al. Phenylpropanolamine and the risk of hemorrhagic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1826-1832.

35 Stempel DA, Thomas M. Treatment of allergic rhinitis: an evidence-based evaluation of nasal corticosteroids versus nonsedating antihistamines. Am J Manag Care. 1998;4:89-96.

36 Benninger MS, Ahmed N, Marple BF, et al. The safety of intranasal steroids. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2003;129:739-750.

37 van Adelsberg J, Philip G, Pedinoff AJ, et al. Montelukast improves symptoms of seasonal allergic rhinitis over a 4-week treatment period. Allergy. 2003;58:1268-1276.

38 Nayak AS, Philip G, Lu S, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of montelukast alone or in combination with loratadine in seasonal allergic rhinitis: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial performed in the fall. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2002;88:592-600.

39 Berger WE. Treatment of allergic rhinitis and other immunoglobulin E-mediated diseases with anti-immunoglobulin E antibody. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2006;27:S29-S32.

40 Hurst DS, Gordon BR, Fornadley JA, et al. Safety of home-based and office allergy immunotherapy: a multicenter prospective study. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121:553-561.

41 Wilson DR, Torres Lima M, Durham SR. Sublingual immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis: systemic review and meta-analysis. Allergy. 2005;60:4-12.

42 Wilson DR, Torres LI, Durham SR. Sublingual immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2003. CD002893.

43 Verhagen J, Blaser K, Akdis CA, et al. Mechanisms of allergen-specific immunotherapy: T-regulatory cells and more. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2006;26:207-231.

44 Bousquet J, Lund VJ, van Cauwenberge P, et al. Implementation of guidelines for seasonal allergic rhinitis: a randomized controlled trial. Allergy. 2003;58:724-726.