Chapter 10 Management of neurological emergencies

Introduction

Neurological emergencies are common but require careful assessment to avoid the pitfalls of missing a serious diagnosis, for example headache presents a particular diagnostic challenge, to avoid missing the one subarachnoid haemorrhage amongst the other benign headaches. This chapter discusses the main neurological conditions and outlines assessment and management based upon current best guidance (Box 10.1).

The primary survey positive patient

The unconscious patient

Ensure the airway is clear and minimise the risk of aspiration by nursing the patient on their side. Give oxygen (15 litres via a non-rebreathing mask) and establish IV access if possible. Transfer to definitive care. Check the blood glucose and assess the Glasgow Coma Score (GCS; Box 10.2). Hypoglycaemia will respond either to 10% glucose IV or IM glucagon administration.

Box 10.2 Glasgow Coma Score

Maximum score = 15, Minimum score = 3

Poisoning and overdose are an important cause of unconsciousness. This is covered more fully in Chapter 14; however it is important that the patient is examined for evidence of IV drug use which might respond to naloxone therapy.

The fitting patient

The fitting patient can provide a significant challenge to the practitioner and attempts should be made to stop the fitting and assess further as required. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) has published guidance on fit management1 (Box 10.3).

Box 10.3 NICE guidance on fit management

If convulsive seizures lasting 5 minutes or longer or three or more seizures in an hour:

Always measure the blood sugar to exclude a hypoglycaemic episode.

Febrile seizures are any seizure occurring in an infant or young child (6 months to 5 years of age) with a fever, or history of recent fever, and without previous evidence of an afebrile seizure or underlying cause. These occur in between 2–4% of all children at some point and a positive family history occurs in up to 40%.2 They can often recur and parental education on treatment can decrease attendance at A&E.

Dealing with these cases can be difficult as parents are often very upset and frightened by the event, requiring a calm and reassuring approach by the healthcare professional. Most children have ceased fitting on arrival and benzodiazepines should be reserved for prolonged seizures – a useful guide is if the child is still fitting on the arrival of assistance. Parents should receive advice regarding febrile seizures after any episode (Box 10.4).

Box 10.4 Advice to parents following a febrile convulsion

Febrile convulsions are common, generally harmless and do not indicate epilepsy or cause brain damage

Febrile convulsions are common, generally harmless and do not indicate epilepsy or cause brain damage They often occur in the first 24 hours of a febrile illness but if they recur the child should be re-evaluated

They often occur in the first 24 hours of a febrile illness but if they recur the child should be re-evaluatedHeadache

The assessment of the patient with headache is difficult even for the most experienced clinician. Headache lends itself very well to assessment via the SOAPC system as by following a careful assessment process an accurate evaluation can be made.3

Subjective assessment

The history is often the most important factor in headache assessment with all information assisting in the final evaluation and decision-making (Box 10.5).

Headache history: The patient who has had regular headaches for many years is more likely to have a migrainous or tension type headache, while the acute onset of headache in a patient who has never had similar previously may indicate serious pathology such as a subarachnoid haemorrhage. In between is the grey area, which is more difficult to interpret accurately, and must trigger caution.

Headache history: The patient who has had regular headaches for many years is more likely to have a migrainous or tension type headache, while the acute onset of headache in a patient who has never had similar previously may indicate serious pathology such as a subarachnoid haemorrhage. In between is the grey area, which is more difficult to interpret accurately, and must trigger caution. Frequency and duration: This is important to distinguish the types of recurrent headache. Migraine often shows a regular pattern of recurrence, while frequent headaches in a short period of time followed by a long, sometimes years, period of remission may indicate cluster headaches. Tension headache has no particular pattern and is often at a background level constantly.

Frequency and duration: This is important to distinguish the types of recurrent headache. Migraine often shows a regular pattern of recurrence, while frequent headaches in a short period of time followed by a long, sometimes years, period of remission may indicate cluster headaches. Tension headache has no particular pattern and is often at a background level constantly. Time of onset: Migraine often causes the patient to wake whilst cluster headaches often occur at certain times. More serious causes have no specific time pattern.

Time of onset: Migraine often causes the patient to wake whilst cluster headaches often occur at certain times. More serious causes have no specific time pattern. Mode of onset: Migraine often has precipitants ranging from an aura (usually visual but may include other focal neurological symptoms), to a feeling of something wrong. Sudden onset or thunderclap headache is suspicious of conditions such as subarachnoid haemorrhage.

Mode of onset: Migraine often has precipitants ranging from an aura (usually visual but may include other focal neurological symptoms), to a feeling of something wrong. Sudden onset or thunderclap headache is suspicious of conditions such as subarachnoid haemorrhage. Site: Migraine, cluster headache and trigeminal neuralgia are commonly unilateral whilst tension headache feels like a tight band around the entire head. Subarachnoid haemorrhage can start locally but usually is generalised and may spread to the neck.

Site: Migraine, cluster headache and trigeminal neuralgia are commonly unilateral whilst tension headache feels like a tight band around the entire head. Subarachnoid haemorrhage can start locally but usually is generalised and may spread to the neck. Associated symptoms: Migraine can commonly give gastrointestinal symptoms, photophobia suggests migraine, meningitis or subarachnoid haemorrhage. Neurological symptoms can occur with migraine but suspicion should be raised about intracranial pathology.

Associated symptoms: Migraine can commonly give gastrointestinal symptoms, photophobia suggests migraine, meningitis or subarachnoid haemorrhage. Neurological symptoms can occur with migraine but suspicion should be raised about intracranial pathology. Precipitating and aggravating factors: Are there any specific triggers the patient can identify? Specific foods, classically chocolate and cheese, can trigger migraine. Aggravation by head movement or coughing/straining suggests raised intracranial pressure.

Precipitating and aggravating factors: Are there any specific triggers the patient can identify? Specific foods, classically chocolate and cheese, can trigger migraine. Aggravation by head movement or coughing/straining suggests raised intracranial pressure. Relieving factors: Patients with a migraine often prefer to lie down in a darkened room whilst patients with cluster headache prefer to move about.

Relieving factors: Patients with a migraine often prefer to lie down in a darkened room whilst patients with cluster headache prefer to move about.It is important to complete the history with a thorough assessment of the patient’s general health and wellbeing including smoking, alcohol and family history.

Objective assessment

Examination of the patient with headache should include a general examination as well as a detailed neurological exam (Box 10.6).

General systems examination: As numerous systemic problems can contribute to headache a full examination is important and may pick up rarer conditions such as endocrine disorders or Marfan’s syndrome.

General systems examination: As numerous systemic problems can contribute to headache a full examination is important and may pick up rarer conditions such as endocrine disorders or Marfan’s syndrome. Mental state/alertness: Depressive affect may be apparent, which is a risk for chronic headache conditions. Drowsiness or confusion suggest intracranial pathology or infection.

Mental state/alertness: Depressive affect may be apparent, which is a risk for chronic headache conditions. Drowsiness or confusion suggest intracranial pathology or infection. Skull: In infants the key finding to look for is a bulging fontanelle, which might indicate intracranial pathology. In adults, especially older, palpation of the temporal arteries may reveal evidence of arteritis. Look for evidence of head injury.

Skull: In infants the key finding to look for is a bulging fontanelle, which might indicate intracranial pathology. In adults, especially older, palpation of the temporal arteries may reveal evidence of arteritis. Look for evidence of head injury. Neck and other tests: Neck stiffness usually indicates meningeal irritation from infection or blood. Kernig’s and Bradzinski’s sign are useful tests for evidence of meningitis.

Neck and other tests: Neck stiffness usually indicates meningeal irritation from infection or blood. Kernig’s and Bradzinski’s sign are useful tests for evidence of meningitis. Eyes: Evidence of glaucoma should be sought as this can present with headache. Fundoscopy should be performed to look for papilloedema or optic atrophy. The cranial nerves controlling eye movements and visual fields can also be tested at this time.

Eyes: Evidence of glaucoma should be sought as this can present with headache. Fundoscopy should be performed to look for papilloedema or optic atrophy. The cranial nerves controlling eye movements and visual fields can also be tested at this time. ENT: It is important to ask about loss of smell and examine the ears for any obvious pathology such as otitis media. Many upper respiratory tract infections have a mild headache as part of their presentation and the throat should be examined for signs of tonsillitis.

ENT: It is important to ask about loss of smell and examine the ears for any obvious pathology such as otitis media. Many upper respiratory tract infections have a mild headache as part of their presentation and the throat should be examined for signs of tonsillitis.Analysis

The cause of most headaches will be clear from the history and examination may add little to the differential diagnosis. Box 10.7 gives the common differential diagnosis of headache. In general, all headaches of acute sudden onset will require immediate investigation in secondary care. The subacute causes of headache will require urgent investigation, either immediately if severe enough or in an urgent outpatient assessment.

Plan and communication

Suspected meningitis, subarachnoid haemorrhage

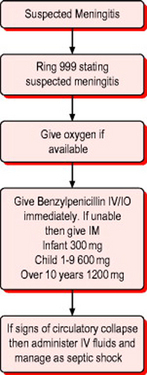

If meningitis is suspected then immediate treatment with benzylpenicillin is warranted unless there is a clear history of immediate anaphylactic reaction following administration previously (Fig. 10.1).

If migraine is suspected then treatment can be started with a non- steroidal anti-inflammatory medication such as diclofenac along with an anti-emetic such as metoclopramide or, if this has been tried and is unsuccessful, a triptan (e.g. sumatriptan) may be given if the patient is less than 65 years old and has no history of heart disease or hypertension.4

Transient ischaemic attack and stroke

Transient ischaemic attack (TIA) is a clinical syndrome characterised by an acute loss of focal cerebral or ocular function with symptoms lasting less than 24 hours. It is thought to be due to inadequate blood supply to these areas as a result of low flow, thrombosis, or embolism associated with diseases of the blood vessels, heart or blood.

Studies put its incidence at 174–216 per 100 000 of the UK population annually and it accounts for 11% of all deaths in England and Wales.5 Approximately 85% of strokes are due to ischaemia and 15% are due to haemorrhage.

The Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party has set out guidelines for the acute management of stroke and TIA6 which are used as the basis for this text.

Subjective and objective assessment

History and examination help define if the symptoms are consistent with a focal neurological deficit from brain ischaemia. Symptoms are more usually negative, e.g. loss of function, rather than positive, e.g. tingling or involuntary movements. Non-focal signs and symptoms such as loss of consciousness, dizziness, weakness, confusion and incontinence are rarely due to a TIA.7

The most sensitive features associated with diagnosing stroke are facial weakness, arm weakness and speech disturbance, with 80% of strokes demonstrating these three features (the FAST assessment – Box 10.8).8

Most areas will have a local protocol for the management of TIA in the acute stages. The difficulty can be distinguishing stroke and TIA in the early stages and unless the patient is clearly recovering hospital assessment is required (Box 10.9). If the patient has recovered then assessment and investigation should be arranged in a specialist clinic, usually within 7 days. In the meantime it is advised that patients have an anti-platelet commenced, with the evidence favouring aspirin 300 mg immediately followed by 75 mg daily due to the increased risk of stroke in the first few days post TIA. If the patient has recurrent episodes of TIA then the regimen should be changed in line with best practice which would generally recommend the addition of dipyridamole.10,11 If there is a second TIA within 7 days then the patient requires hospital admission.

There is often little to do in the emergency situation for patients who have had an acute stroke. Those who are unconscious, or primary survey positive, will require appropriate management and immediate transfer to hospital (Box 10.10). Those patients who are not primary survey positive should be assessed using a standard SOAPC approach (see Chapter 2) prior to dispatch to hospital.

Important observations should be recorded including blood pressure, pulse, heart rhythm, temperature, blood glucose and, if possible, oxygen saturations. Blood sugar is important as hypoglycaemia or diabetic coma can present with similar features to acute stroke.

1 National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. The epilepsies: diagnosis and management of the epilepsies in adults in primary and secondary care. London: NICE, 2004.

2 Warden CR, et al. Evaluation and management of febrile seizures in the out-of-hospital and emergency department settings. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;41:215-222.

3 Lance J W, Goadsby PJ. Mechanism and management of headache. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann, 1999.

4 Goadsby PJ, et al. Migraine – current understanding and treatment. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:257-268.

5 Mant J, et al. Health care needs assessment: the epidemiologically based needs assessment reviews, 2nd edn. Oxford: Radcliffe Medical Press, 2004.

6 Intercollegiate Stroke Working Party. National clinical guidelines for stroke, 2nd edn. London: Royal College of Physicians, 2004.

7 Shah K, Edlow J. Transient ischaemic attack: review for the emergency physician. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:592-603.

8 Joint Royal Colleges Ambulance Liason CommitteeTodd I. Clinical practice guidelines for use in UK ambulance services. London: JRCALC, 2004. Available online: http://www.nelh.nhs.uk/emergency (5 Mar 2007)

9 Bath PMW, Lees KR. ABC of arterial and venous disease – acute stroke. BMJ. 2000;320:920-923.

10 Tran H, Anand S. Oral antiplatelet therapy in cerebrovascular disease, coronary artery disease, and peripheral arterial disease. JAMA. 2004;292:1867-1874.

11 Antithrombotic Trialists’ Collaboration. Collaborative meta-analysis of randomised trials of antiplatelet therapy for prevention of death, myocardial infarction, and stroke in high risk patients. BMJ. 2002;324:71-86.