Chapter 147 Management of Neurocysticercosis

A number of parasitic infections can invade the central nervous system (CNS) despite the protection provided by the blood–brain barrier. Included are trypanosomiasis, malaria, toxoplasmosis, free-living amoebal infections, echinococcosis, schistosomiasis, and helmintic infections, among others.1–8 Of these, neurocysticercosis (NCC) is the most common one in developing countries in Latin America, east and south Asia, and in sub-Saharan Africa; however, its incidence has increased in industrialized countries due to immigration of infected individuals.9–11 NCC is highly correlated to poor sanitation and shortage of economic resources.12,13 It is also the most common parasitic infection of the CNS and the most frequent cause of acquired epilepsy in developing countries,14,15 and is an emerging public health issue in industrialized countries.16

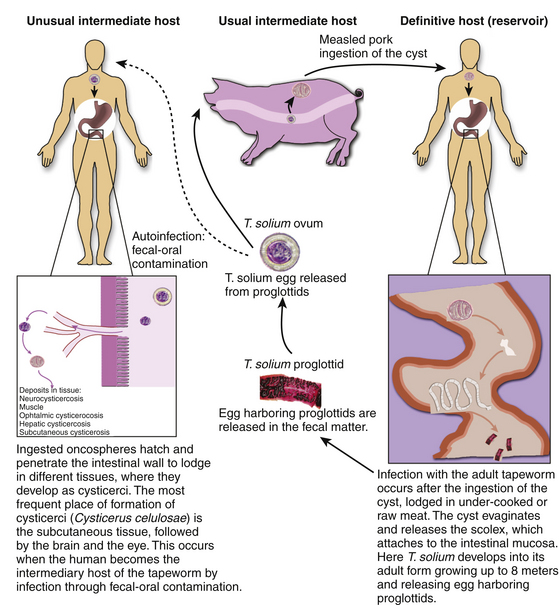

Neurocysticercosis is the consequence of infection of the human CNS by the pork tapeworm, Taenia solium, in its larval stage when the human becomes the intermediary host.17 This occurs after the ingestion of eggs released from gravid proglottids, which are shed by adult tapeworms.18 Lack of hygiene and sanitary measures promote the spread of this parasitic disease due to contamination of foodstuffs with feces of human carriers of the tapeworm.19

Historical Background

The larval stage (Cysticercus cellulosae) of the porcine tapeworm Taenia solium, has been recognized in pigs for more than two millennia, and intestinal parasites were identified as worms. In ancient Greece, Hippocrates, Aristotle, and Theophrastus called them “flat worms,” likely based on Aristotle’s Historia Animalum20 due to their resemblance to a tape or band, while Celsus, Pliny, and Galen called these parasites Lumbricus latus or wide worm.21

The Taenia solium species of tapeworm was described initially by Villanovani with a term that reflected the notion that an individual could only carry one of these parasites.22 In 1683 Tyson described the head of taenias, and later pictures of the scolex of these parasites were published.21,23

In 1855, Kuchenmeister identified the relationship between the ingestion of cysticerci and the development of teniasis.21,24 In an anecdote, the method to identify cysticerci is found in a play by Aristophanes of Athens entitled, “The Knights,” where he describes “let us force a stake into his mouth as cooks do, and then, by pulling out his tongue, we will examine boldly at our ease his wide opened mouth to see if he is measled”.21,25 van Benedem 1853 demonstrated the formation of cysticerci in swine after feeding them with eggs of T. solium and finding evidence of cysticercosis in the muscle after slaughtering them.26

More accurate reports of cysticercosis in the nervous system in humans were made by Rumler in 1558 when he described a “tumor in the dura mater of an epileptic patient”.21,27 Panarolus described cysts in the corpus callosum,28 as well as Wharton, who identified multiple cysts in adipose tissue and muscle, thinking that they were glands.25 As a disease, Malpighi described the animal nature of this parasite as well as its cyst and scolex in 1968.25

The concept of cysticercus cellulosae was described initially by Zeder; however, it was later determined that this was a phase of the larva during development of the cysticercus.21,29 Evidence of the life cycle of the parasite, and its interaction with specific communities was clearly established in Dixon’s study where he found infestations in British soldiers 5 years after their stay in India. He found a high prevalence of neurologic symptoms associated with cysticercosis.30 Currently, the international consensus defines teniasis as the intestinal infestation stage, and cysticercosis is defined as the larva infestation, which occurs in multiple tissues throughout the body.

Epidemiology

The incidence of NCC varies by continent; however, it is the most frequent parasitic disease that affects the CNS.14 It is endemic in countries of Africa, Central and South America, and Southeast Asia.31–34 Symptoms of the disease can present between 2 months and 30 years after the initial infection.

Subcutaneous nodules may be present in infected patients. However, the extraneural form of this disease usually has a benign course. Involvement of the CNS is generally a consequence of cerebral pathology, with lesser involvement of the spine.11 Neurologic implications of this disease are relevant: NCC is the cause of 12% of hospitalizations and the most common cause of acquired or late onset epilepsy in countries of Latin America.35,36 Patients suffer severe neurologic complications at productive ages. Further, it is considered that more than 50,000 deaths worldwide are related to NCC, making this disease a major public health issue.37,38

Parasitic Life Cycle

The etiologic agent of cysticercosis is the Taenia solium at its larval stage, the cysticercus cellulosae Taenia solium has a two-host complex life cycle. The human is the definitive host for the adult and the pig is the intermediate host for the larval cysticercus. However, the human can also serve as the intermediate host after ingestion of T. solium eggs.6,17

Humans become infected with tapeworm after ingesting pork meat containing cysticerci, the larval form of the parasite in the first stage of infection. In the small intestine, the scolex evaginates and attaches to the mucosa where it grows into the adult form of the tapeworm in the second stage; humans develop intestinal teniasis. The adult tapeworm is hermaphrodite and has multiple segments, each containing a branched uterus laden with infective eggs called proglottids, which it sheds into the fecal matter approximately 4 months after attachment during the third stage of infection. The adult tapeworm can be live up to 25 years. They remain viable several weeks in contaminated soil after excretion. The eggs are disseminated in the environment and are later ingested by pigs and humans. This entails fecal–oral transmission of infective eggs to humans as autoinfection or transmission to other individuals. Another possible but unlikely mechanism of development of cysticercosis is by retrograde peristalsis with the subsequent penetration of the mucosa by the larvae (Fig. 147-1). All of these mechanisms occur because of poor hygiene, such as failure to wash hands before meals and after defecation, or contamination of water or food with feces of carriers of the adult tapeworm.

A high proportion of tapeworm carriers as well as their family members develop cysticercosis after ingestion of the infective eggs.13,39 In the intestine, the egg becomes the oncosphere that penetrates the intestinal mucosa entering local lymphatic and mesenteric vessels and different tissues and organs during the fourth stage. It lodges mainly in subcutaneous tissue, the brain, and muscle. The fifth stage is the postoncospheral form, followed by the sixth and last stage, the cysticerci, that gives clinical manifestations according to the tissue and location of implantation.13,40

Cysticerci are vesicles with two main parts: the vesicular wall and the scolex. The scolex has a similar structure to the adult form of T. solium, consisting of an armed rostellum and a body. They usually lodge in anatomic sites with abundant vascular supply, such as the cortex or basal ganglia. The macroscopic view of cysticerci varies according to their location in the CNS. For example, in the brain parenchyma the cysticercus measures approximately 10 mm, but in the subarachnoid space, they can grow up to 50 mm. Meningeal cysts adhere to the pia or float freely, particularly in the sylvian fissure. With time, cysticerci tend to shrink, and the meninges become thickened and fibrotic. Some cysts appear as a grape-like cluster, attached to each other by several membranes and giving rise to the racemose form of the disease. Racemose cysticercosis consists of a large multiloculated mass of cysticerci that lack an invaginated scolex. They are usually in the basilar cisterns and the fourth ventricle. In ventricular cysticercosis, a single cyst is found adhering to the ependymal wall or the choroid plexus; however, it is possible to see them floating in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).41

Pathogenesis and Microscopic Appearance

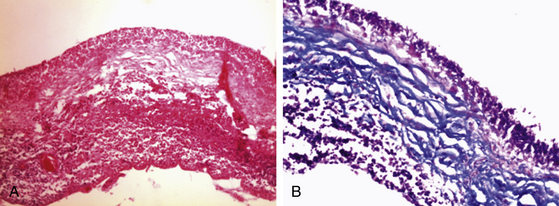

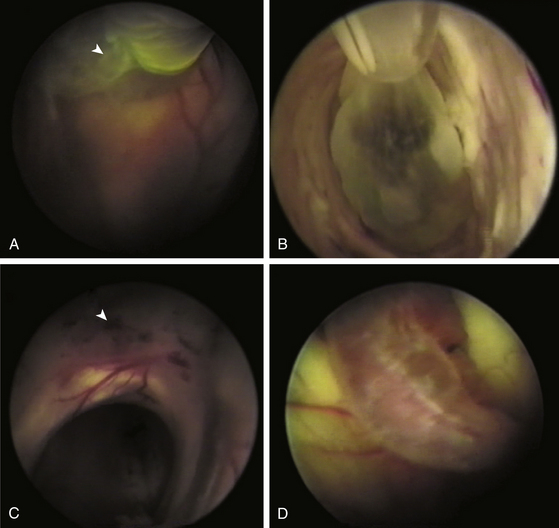

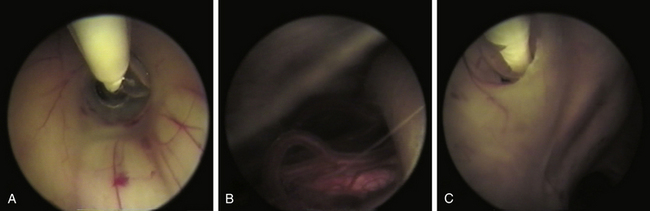

In the CNS, cysticerci induce an inflammatory response in surrounding tissues. Initially, in the vesicular stage of the cysticercus, inflammatory reaction is minimal; it has a transparent membrane, clear fluid inside, and integrity of the larva and scolex. In the colloidal stage, the cyst shows degenerative changes due to factors such as inflammatory reaction and pharmacologic therapy. When the disease is the colloidal stage, the scolex is lost and inflammatory cells, mainly mononuclear/macrophages, penetrate the cyst. In this stage, the fluid becomes turbid and viscous. Later, in the nodular stage, the cyst is enclosed by a zone of granulation tissue with a dense capsule of collagen, which shows astrocytic gliosis, microglial proliferation and activation, edema, perivascular cuffing, and presence of necrotic tissue and cholesterol clefts. Old nodules may be fibrotic and sometimes become mineralized (calcifications). Ventricular cysticerci usually cause granular ependymitis, especially with high doses of cysticidal treatment. Degeneration of racemose cysticerci may cause a granulomatous inflammatory reaction in the subarachnoid space with accumulation of collagen, lymphocytes, multinucleate giant cell, eosinophils, and hyalinized parasitic membranes that have as a consequence leptomeningitis, chronic basilar arachnoiditis, opto-chiasmal arachnoiditis, or hydrocephalus. Consequently, CSF absorption capacity declines, causing hydrocephalus.42 Endoscopically, it is possible to visualize an inflammatory reaction in the choroid plexus and ventricular wall in ventricular cysticercosis. Microscopically, it is possible to identify a disrupted ependymal lining that is replaced by subependymal glial cells. This is an important cause of CSF blockage in narrow spaces such as the cerebral aqueduct and interventricular foramina.

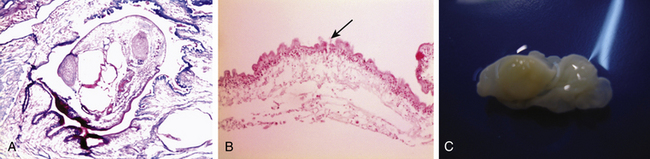

Microscopically, the parasite has a scolex has a rostellum provided with four suckers and a double row of 22-32 hooklets. The cystic wall consists of three different layers (Figs. 147-2 and 147-3):

• External layer (cuticular), 3 μm thick, eosinophilic, with hair-like protrusions called microtrichia

• Inner reticular layer (fibrillary), which may contain mineral concretions.

Initially the parasite is able to evade the host’s immune response by secreting humoral factors that inhibit activation of complement and lymphocytes, the secretion of cytokines, and secretion of prostaglandins that decrease inflammation and manipulate the immune reaction to activate production of T-helper 2 molecules. The cysticercus secretes proteases that cleave interleukins and structural components in its wall that inhibit complement activation.11 On the other hand, patients with acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) respond differently to the parasite. It has been reported that the incidence of NCC in patients with AIDS has increased, while other reports have found that there is no predisposition of these patients to NCC, suggesting that humoral immunity is more relevant to combat NCC than cellular immunity.

Deposits of immunoglobulin (Ig) E and IgG have been found surrounding cysticerci. Moreover, there are numerous reports of patients that have lesions at different stages, suggesting that the immune reaction against these parasites is heterogeneous while also presenting the possibility of reinfection.35,42,43

Clinical Manifestations

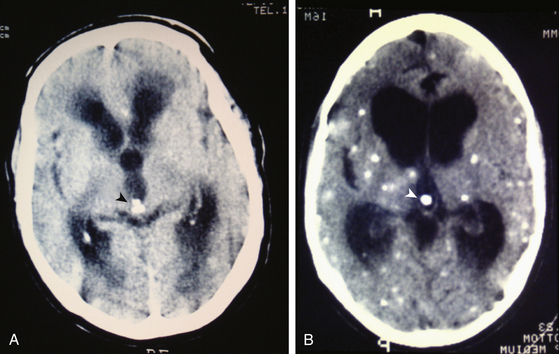

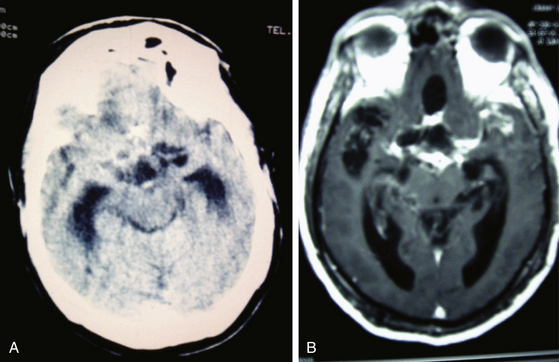

Leptomeningitis is the next most frequent clinical manifestation presenting with hydrocephalus or basilar arachnoiditis44 (Fig. 147-4). Also, when cysticerci are present in the ventricles or subarachnoid space, the flow of CSF can be obstructed by granular ependymitis and by occlusion of interventricular foramina by parasites. As a consequence, patients suffer hydrocephalus and intracranial hypertension, which may become chronic and carries numerous complications and disability.35,41,43,45,46

Another important condition related to chronicity, high level of complications, and disability, is intracranial hypertension due to hydrocephalus. This condition occurs as a consequence of arachnoidits, granular ependymitis, or the presence of cysticerci in the ventricular cavity. The Bruns phenomenon is a usual condition when csycticerci are free and floating in the ventricular space, with acute clinical manifestations, requiring emergent surgical intervention. Cysticercal encephalitis is a rare presentation and is most common in children and young women.47 It occurs as a consequence of a massive cysticercal infection accompanied with important edema probably due to the host’s immune reaction or, in our experience, also in reaction to drug therapy, with hyper-reaction after the parasite died. The clinico-topographic presentation follows: parenchymal, meningeal, ventricular, cerebrovascular disease (vasculitis), encephalitis, disseminated, neurocognitive disorders, and spinal (radicular pain, transverse myelitis or medullar syndrome).

Diagnosis

Until now the best way to understand the clinical spectrum of NCC is through diagnostic criteria, based in clinical, radiologic, immunologic, and epidemiologic data.48,49 These diagnostic criteria are listed in Table 147-1.

CST, cerebrospinal fluid; CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance image; NCC, neurocysticercosis.

Laboratory Studies

Cerebrospinal fluid examination. Abnormalities in cytochemical examination of the CSF are found in approximately 80% of patients with the active NCC. These abnormalities have a clear correlation with the form and location of the parasites. The most usual finding is the mononuclear pleocytosis, with an average of 300 cells/mm3, but may be higher in cases of cysticercal meningitis. Elevated protein levels (50–300 mg/dl) and normal glucose levels are also found in CSF analysis. Low levels of glucose levels have been associated with poor prognosis. However, normal CSF does not rule out the diagnosis of NCC.

In patients where imaging studies do not provide conclusive diagnostic information, immunodiagnostic testing is an important tool. However, a real problem is the variability of the humoral immune response of the host against cysticerci as well as the evasion of the immune system by the parasite; consequently, these tests have a high rate of false-positive and -negative results.

The first immunologic test described was Nieto’s reaction by complement fixation with sensitivity of 83%, but only 22% in cases with parenchymal cysticercosis with normal cytochemical analysis of CSF. Complement fixation tests have less sensitivity in cases of ventricular or subarachnoid cysticercosis.50

IgM detection by ELISA (enyzme-linked immunoassay) has a sensitivity of around 95% and 87% in active and inactive cases of NCC, respectively.51 CSF examination is preferable to serum, due to a 30% rate of false-negative results and a high false-positive rate due to cross-reactivity with other parasites.52 Immunoblotting diagnostic techniques in serum and CSF have been used since an 18-kDa band has been identified in the antigen protein profile; however, it cross-reacts with antigens of Taenia crassiceps.53

Other bands (GP13, GP14, GP24, and GP 39-42) are also recognized antigens, in the EITB assay (enzyme-linked immunoelectrotransfer blot). Some authors reported high sensitivity and specificity in the diagnosis of cysticercosis, but evidence is still lacking. This test may yield false negative results in the case of a single cerebral cyst, and may be positive in cases of teniasis.54,55

Recently, more attention has been focused on prevention in endemic areas. Indeed, the high prevalence of teniasis and its relation to NCC suggests that the fecal–oral route of infection is of great importance. The detection of T. solium carriers through stool specimen testing is paramount to preventing dissemination of the disease in respective communities. Because detection of T. solium eggs detection is not easy, immune-diagnostic testing in serial stool specimens may prove useful. This is the case of ELISA coproantigen detection test, and a more specific test such as DNA hybridization for egg identification.11

Neuroimaging Diagnosis

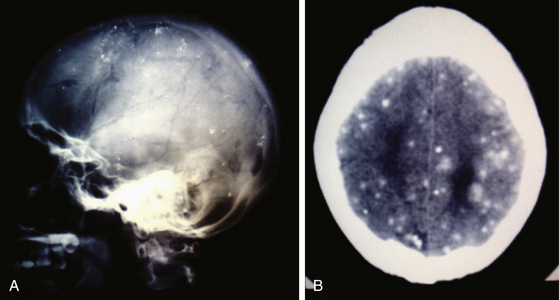

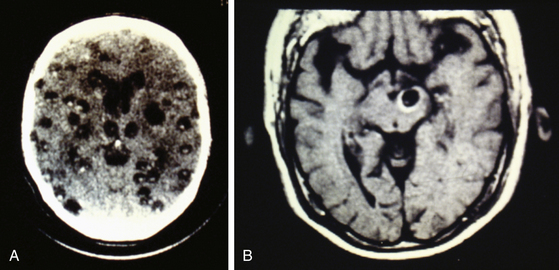

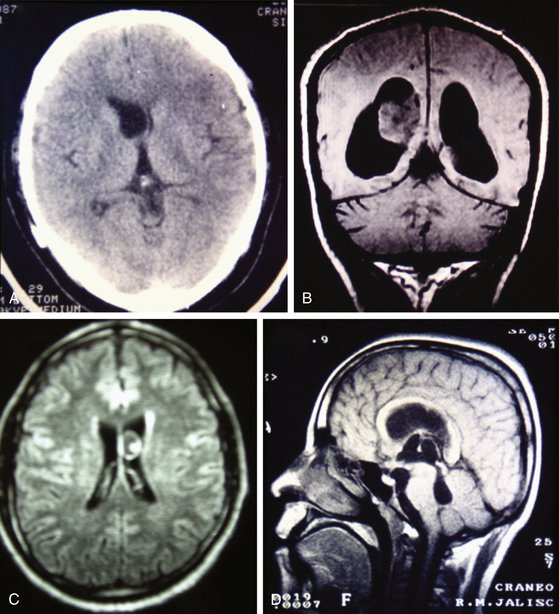

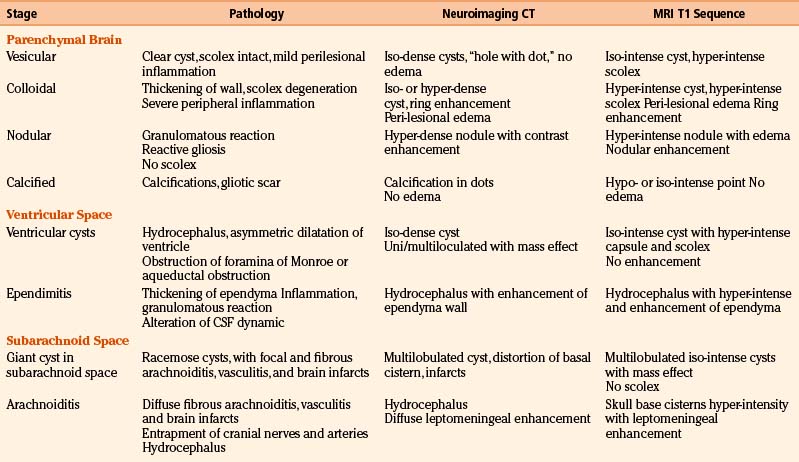

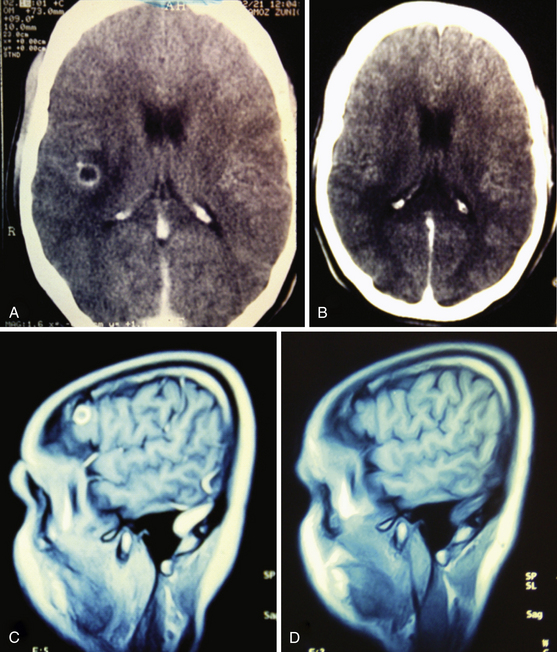

Radiologic diagnosis of chronic inactive NCC can be considered upon discovery of ellipsoidal calcifications in skull x-rays or computerized axial tomography scans (CT scans) (Fig. 147-5). CT scans are still the best option in radiologic studies to identify calcifications in the parenchyma as well as in the intraventricular space. Neuroimaging studies show viable cysticerci as a hyperdense nodule with the scolex included, resembling a hole with a dot (Fig. 147-6). Active cysts appear as ring-enhancing lesions in studies with contrast. When big lesions are identified with these characteristics, it is important to consider in the differential diagnosis pyogenic abscess, fungal abscess, tuberculomas, abscess by tocoplasma, and primary brain tumors.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is currently the gold standard for diagnosis by imaging. It is better than CT scan for diagnosis in patients with cysticerci lodged in the brain stem (Fig. 147-6B), skull base, intraventricular space (Fig. 147-7), and spinal lesions, but it fails to detect small calcifications. This is an important point because in some patients, calcifications are the only evidence of chronic inactive NCC. In selected cases, spectroscopy is useful to differentiate NCC from primary brain tumors. Functional MRI (fMRI) is useful in operative planning to preserve primary functional areas of the brain during resection of these lesions. It is necessary to keep in mind that characteristics of these lesions depend mainly on the developmental stage of the parasite and on the pathophysiologic form of presentation of the disease. Besides visualization of the cyst, it is possible to find hydrocephalus (Fig. 147-8), ischemic infarctions (complemented by angiography), and abnormal enhancement of the leptomeninges (Fig. 147-9). MRI is a more sensitive test for the diagnosis of active NCC since 40% of patients with active disease have normal CT scans.35,41,43,56 Imaging findings according to different techniques are found in Table 147-2.

Pharmacologic Treatment

Cysticidal Treatment

Praziquantel (isoquinolein-pirazine) has been used to treat human cysticercosis for approximately 30 years. It has been used previously in schistosomiasis and it has adequate absorption and low toxicity. It penetrates the blood–brain barrier and reaches one-seventh of the concentration in serum in CSF. For this reason, the drug is a good choice for parenchymal and subarachnoid NCC. Praziquantel is effective in eliminating 70% of parenchymal cysticerci after a 15-day course of treatment at daily doses of 50 mg/kg. Recent studies show that a short treatment can be effective based on pharmacokinetics. The cysticidal effect is achieved by several intermittent peaks of the drug in contact with the parasite, depending on plasma level and half-life. Based on this, authors suggest high frequent doses of praziquantel for up to 6 hours (three doses of 25–30 mg/kg at 2-hour intervals on a single day) are sufficient to eliminate the parasite. Close surveillance of the patient is mandatory with this treatment due to potential toxicity of parasitic proteins released after the elimination of the parasite, which may start an acute immune reaction.35,57,58

Albendazole (benzimidazole) is another good choice for cysticidal therapy. It is advantageous to praziquantel since it destroys subarachnoid and ventricular cysts as it reaches higher concentrations in the CSF. Also, it has less pharmacologic interactions, allowing for concomitant use of steroidal anti-inflammatory agents, and is less expensive. Albendazole therapy destroys 75% to 90% of parenchymal brain cysts, after a treatment of 15 mg/kg/day for 1 month. Similarly, studies have shown that a short course therapy of 1 week is also effective.25,59

Recently, the use of ivermectine has been proposed as an alternative treatment for parasites that demonstrate resistance to conventional treatment. However, there are only a few case reports where this has been used as cysticidal therapy and consistent evidence is lacking46,60 (Fig. 147-10).

Anti-Inflammatory Therapy

Corticosteroid therapy should be considered because inflammation is a characteristic feature of NCC in the active stages of the disease. An important inflammatory reaction is also present within the first 3 days of pharmacologic treatment, specifically in brain parenchyma. A local cellular immune reaction results after rupture of the cyst consisting of eosinophils and lymphocytes followed by macrophages. This reaction may be different depending on the location of the lesion and the host. For example, it is possible that the patient presents with severe arachnoiditis or hydrocephalus after pharmacologic treatment of an intraventricular cyst. Other related complications include cranial neuropathies due to entrapment of nerves with progressive chronic changes. In these cases the use of 30 mg/kg/day of dexamethasone is recommended, followed by a chronic oral therapy with prednisone (50 mg/day). Not all cases require corticosteroid treatment; thus each case should be evaluated individually. Absolute indications for corticosteroid during cysticidal treatment are giant subarachnoid cysticerci, intraventricular cysts, spinal cysts, and multiple parenchymal brain cysts.35 Aspirin can be used for the treatment of patients with evidence of vasculitis.

Symptomatic Therapy

The vast majority of patients with NCC will require symptomatic therapy depending on the chief complaint and clinical presentation. Anticonvulsant therapy is frequently needed in these patients. Seizure control is more effective after cysticidal therapy; however, seizures may present during pharmacologic treatment of the disease even if the patient did not present them initially. Long-term benefit of seizure control has been questioned recently in a report by the Cochrane Foundation.61 In some patients with seizures, it will be possible to discontinue anticonvulsant therapy after 2 years without seizures and evidence of elimination of cysticerci. Nevertheless, a prospective study demonstrated recurrence of seizures in around 50% of these patients. Development of calcifications as a result of treatment, recurrent seizures, and multiple brain cysts have been reported as factors of poor prognosis.62

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are effective in the control of headache; however, when the headache has a vascular component, beta-blockers and vasodilators should be used. Tricyclic antidepressants and anxiolytics are used when there is a component of tension headache. Headache also develops during pharmacologic treatment due to the local inflammatory process, edema, and intracranial hypertension. Mannitol can be used when patients present neurologic signs of intracranial hypertension.

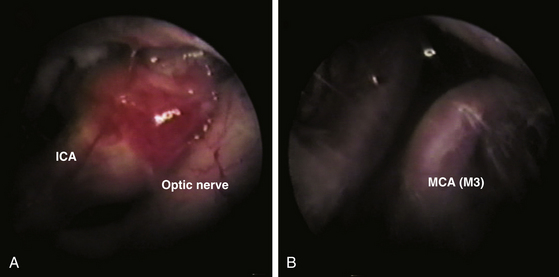

Surgical Treatment

Currently surgical treatment is the primary treatment for NCC in selected cases because pharmacologic treatment is not innocuous and the advent of new surgical techniques have decreased morbidity and mortality associated with surgical procedures.35,43,46 Minimally invasive techniques have been shown to be effective as a principal strategy in many cases63 that are complemented with cysticidal therapy (Fig. 147-11). Discouraging results reported in various surgical series were related to patient profiles and not to surgical morbidity. Patients had severe disease, previous attempts of treatment had failed, and had received high doses of cysticidal drugs along with secondary effects. This yielded a surgical mortality of approximately 21% in the long-term follow-up of these patients.45 One of the most common procedures has been the control of intracranial pressure in cases of hydrocephalus with the implantation of a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt, which had a high dysfunction rate due to the high cellular and protein contents in the CSF, as well as the contents of remnants of cysticerci, secondary ependymitis, and eventually infection. Other series reported mortality as high as 50%, directly related to the number of surgical interventions necessary for shunt revision.35 In patients with NCC, failure in shunt function is also related to the presence of transit inversion of CSF with inflammatory cells and granulomatous infiltration of the ependymal wall.

1. Severe intracranial hypertension secondary to mass effect of cysts in the parenchyma, subarachnoid space or in the ventricles.

2. Ventricular or subarachnoid cysts accessible with endoscopic or minimally invasive techniques.

3. Obstructive hydrocephalus, considering resection of cysts that block the flow of CSF. This should be complemented with third ventriculostomy (Fig. 147-12). Intracranial pressure monitoring will determine the implantation of a permanent ventriculoperitoneal shunt in those cases that do not resolve intracranial hypertension or those where the third ventriculostomy fails.

4. Medullary syndrome due to compression and mass effect of cysts.43,46

Surgical treatment will be complemented with cysticidal treatment in all cases. Features of poor prognosis include: location of cysts in the basal cisterns in patients younger than 40 years with severe inflammatory reaction, patients with ventricular granulomatous septa, and patients requiring multiple procedures for review and change of shunts. Patients with cysticercal encephalitis, which is more common in young adults and children,47 may eventually require bilateral decompressive craniectomy, when the intracranial pressure is not controlled with medical treatment.

Simplified descriptions for the treatment of different types of NCC are included in Tables 147-3, 147-4, and 147-5.

| Clinical Presentation | Management Strategy |

|---|---|

| Small and asymptomatic | Pharmacologic treatment Imaging follow-up |

| Symptomatic Mass effect/parenchymal brain cyst included Racemose giant cyst with increase in size |

Surgical excision before cysticidal therapy (minimally invasive neurosurgery) |

TABLE 147-4 Management of Parenchymal Brain and Spinal Cysts

| Clinical Presentation | Management Strategy |

|---|---|

| Small incidental or mildly symptomatic cyst | Pharmacologic treatment |

| Giant cyst with mass effect Evolutive increase Primary symptomatic or deteriorated after medical treatment |

Surgical excision before cysticidal therapy (minimally invasive neurosurgery) |

TABLE 147-5 Management of Intraventricular Cysts (Before Cysticidal Therapy)

| Clinical Presentation | Management Strategy |

|---|---|

| Free or adherent | Endoscopic excision |

| Obstruction by cyst, ventricular dilatation | Endoscopic excision/third ventriculostomy |

| Hydrocephalus | Endoscopic exploration and excision Third ventriculostomy Septum fenestration |

| Inflammatory ependymitis | No patency of third ventriculostomy Recurrence of increased ICP Ventriculoperitoneal shunt |

ICP, intracranical pressure.

Prevention and Sanitary Recommendations

Neurocysticercosis is highly correlated with conditions of poverty and its social impact, and mainly in insufficient sanitary measures in developing countries. Consequently, education on sanitation and hygiene is the most important strategy for the control of this disease. It should be oriented toward control and eradication of the parasite in carriers. Hand-washing procedures before each meal and after defecation, as well as consumption of clean and boiled water in endemic areas will be paramount. Installation of latrines or other hygienic measures for disposal of human waste are pivotal to control dissemination of this disease. Adequate care of porcine herds to prevent human infection with the intestinal form will also be important. These elemental measures will have an important preventive impact and should be complemented with cysticidal treatment to endemic populations to eliminate human infection with the adult tapeworm and the subsequent infection of humans and pigs. Currently, NCC is a public health issue even in developed countries due to the migration of people carrying the parasite from endemic areas. This makes cysticercosis the parasitic disease with largest impact on the CNS.38,64

Alarcon F. Neurocysticercosis: its aetiopathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Rev Neurol. 2006;43(Suppl 1):S93-S100.

Carpio A. Neurocysticercosis: an update. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2(12):751-762.

Coker-Vann M.R., et al. ELISA antibodies to cysticerci of Taenia solium in human populations in New Guinea, Oceania, and Southeast Asia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1981;12(4):499-505.

Colli B.O., et al. Surgical treatment of cerebral cysticercosis: long-term results and prognostic factors. Neurosurg Focus. 2002;12(6):e3.

Commission on Tropical Diseases of the International League against Epilepsy. Relationship between epilepsy and tropical diseases. Epilepsia. 1994;35(1):89-93.

Corona T., et al. Single-day praziquantel therapy for neurocysticercosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(2):125.

DeGiorgio C.M., et al. Neurocysticercosis. Epilepsy Curr. 2004;4(3):107-111.

Del Brutto O.H., et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for neurocysticercosis. Neurology. 2001;57(2):177-183.

Del Brutto O.H. Prognostic factors for seizure recurrence after withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs in patients with neurocysticercosis. Neurology. 1994;44(9):1706-1709.

Garcia H.H., Del Brutto O.H. Taenia solium cysticercosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2000;14(1):97-119. ix

Garcia H.H., et al. Albendazole therapy for neurocysticercosis: a prospective double-blind trial comparing 7 versus 14 days of treatment. Cysticercosis Working Group in Peru. Neurology. 1997;48(5):1421-1427.

Garcia H.H., et al. New concepts in the diagnosis and management of neurocysticercosis (Taenia solium). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72(1):3-9.

Gimenez-Roldan S., Diaz F., Esquivel A. [Neurocysticercosis and immigration]. Neurologia. 2003;18(7):385-388.

Medina M.T., et al. Neurocysticercosis as the main cause of late-onset epilepsy in Mexico. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(2):325-327.

Miller B.L., et al. Cerebral cysticercosis: an overview. Bull Clin Neurosci. 1983;48:2-5.

Ramirez-Zamora A., Alarcon T. Management of neurocysticercosis. Neurol Res. 2010;32(3):229-237.

Ramos-Kuri M., et al. Immunodiagnosis of neurocysticercosis. Disappointing performance of serology (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) in an unbiased sample of neurological patients. Arch Neurol. 1992;49(6):633-636.

Roman G., et al. A proposal to declare neurocysticercosis an international reportable disease. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(3):399-406.

Rosas N., Sotelo J., Nieto D. ELISA in the diagnosis of neurocysticercosis. Arch Neurol. 1986;43(4):353-356.

Sinha S., Sharma B.S. Neurocysticercosis: a review of current status and management. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16(7):867-876.

Sorvillo F.J., DeGiorgio C., Waterman S.H. Deaths from cysticercosis, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(2):230-235.

Sotelo J., Marin C. Hydrocephalus secondary to cysticercotic arachnoiditis. A long-term follow-up review of 92 cases. J Neurosurg. 1987;66(5):686-689.

Sotelo J., Del Brutto O.H. Review of neurocysticercosis. Neurosurg Focus. 2002;12(6):e1.

Walker M., Zunt J.R. Parasitic central nervous system infections in immunocompromised hosts. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(7):1005-1015.

White A.C.Jr. Neurocysticercosis: updates on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:187-206.

1. Shahlaie K., et al. Parasitic central nervous system infections: echinococcus and schistosoma. Rev Neurol Dis. 2005;2(4):176-185.

2. Herman J.S., Chiodini P.L. Gnathostomiasis, another emerging imported disease. Clin Microbiol Rev.. 2009;22(3):484-492.

3. Kennedy P.G. Human African trypanosomiasis-neurological aspects. J Neurol. 2006;253(4):411-416.

4. Kennedy P.G. Diagnostic and neuropathogenesis issues in human African trypanosomiasis. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36(5):505-512.

5. Medana I.M., Turner G.D. Human cerebral malaria and the blood-brain barrier. Int J Parasitol. 2006;36(5):555-568.

6. Sinha S., Sharma B.S. Neurocysticercosis: a review of current status and management. J Clin Neurosci. 2009;16(7):867-876.

7. Visvesvara G.S., Stehr-Green J.K. Epidemiology of free-living ameba infections. J Protozool. 1990;37(4):25S-33S.

8. Walker M., Zunt J.R. Parasitic central nervous system infections in immunocompromised hosts. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(7):1005-1015.

9. Miller B.L., et al. Cerebral cysticercosis: an overview. Bull Clin Neurosci. 1983;48:2-5.

10. Sorvillo F.J., DeGiorgio C., Waterman S.H. Deaths from cysticercosis, United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 2007;13(2):230-235.

11. White A.C.Jr. Neurocysticercosis: updates on epidemiology, pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Annu Rev Med. 2000;51:187-206.

12. Sarti E., et al. Prevalence and risk factors for Taenia solium taeniasis and cysticercosis in humans and pigs in a village in Morelos, Mexico. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1992;46(6):677-685.

13. Carpio A. Neurocysticercosis: an update. Lancet Infect Dis. 2002;2(12):751-762.

14. DeGiorgio C.M., et al. Neurocysticercosis. Epilepsy Curr. 2004;4(3):107-111.

15. Medina M.T., et al. Neurocysticercosis as the main cause of late-onset epilepsy in Mexico. Arch Intern Med. 1990;150(2):325-327.

16. Wallin M.T., Kurtzke J.F. Neurocysticercosis in the United States: review of an important emerging infection. Neurology. 2004;63(9):1559-1564.

17. Garcia H.H., Del Brutto O.H. Taenia solium cysticercosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2000;14(1):97-119. ix

18. Garcia H.H., et al. New concepts in the diagnosis and management of neurocysticercosis (Taenia solium). Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72(1):3-9.

19. Medina M.T., DeGiorgio C. Introduction to neurocysticercosis: a worldwide epidemic. Neurosurg Focus. 2002;12(6):1.

20. Scarborough J. Theophrastus on herbals and herbal remedies. J Hist Biol. 1978;11(2):353-385.

21. Flisser A. Taeniasis and cysticercosis due to Taenia solium. In: Sun T., editor. Progress in Clinical Parasitology. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 1994:77-116.

22. Villanovani A. De lumbricus et ascaridibus. Opera omnia. 1585, Basileae.

23. Tyson E. Lumbricus latus. Discourse read before the Royal Society. Philosoph Trans R Soc. 1683;13:113-144.

24. Kuchenmeister F. Experimentelles nachweis, dass cysticercus cellulosae innerhalb des menschlichen darmkanales sich in Taenia Sollium umwandelt. Wiener medizinische Wochen-schrift. 1855;5:1-4.

25. Flisser A., Madrazo I., Delgado H. Cisticercosis Humana. Mexico City: Manual Moderno; 1997.

26. Van Beneden P. Note sur des experiences relatives au developpement des cysticerques. Ann Sci Nat. 1854:1-104.

27. Rumler J. Secto a me, in capite pustulae supra duram meningen apparuerunt, erosa ipsa et cerebro pero foramina eminente pluribus in locis. Observationes Medicae. 1558.

28. Panarolus D. Iatrologismorum, seu medicinalium observationum pentecostae quinque. Rome: F Moneta; 1652.

29. Zeder J. Anleitung zur naturgeschichte der eingeweidewurmer. Bamberg; 1803.

30. Dixon H., Lipscomb F. Cysticercosis: an analysis and follow-up of 450 cases. Proc R Soc Med. 1962;55(3):1-58.

31. Ramirez-Zamora A., Alarcon T. Management of neurocysticercosis. Neurol Res. 2010;32(3):229-237.

32. Coker-Vann M.R., et al. ELISA antibodies to cysticerci of Taenia solium in human populations in New Guinea, Oceania, and Southeast Asia. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1981;12(4):499-505.

33. Fleury A., et al. High prevalence of calcified silent neurocysticercosis in a rural village of Mexico. Neuroepidemiology. 2003;22(2):139-145.

34. Mafojane N.A., et al. The current status of neurocysticercosis in Eastern and Southern Africa. Acta Trop. 2003;87(1):25-33.

35. Sotelo J., Del Brutto O.H. Review of neurocysticercosis. Neurosurg Focus. 2002;12(6):e1.

36. Commission on Tropical Diseases of the International League against Epilepsy. Relationship between epilepsy and tropical diseases. Epilepsia. 1994;35(1):89-93.

37. Gemmell M., et al. Guidelines for Surveillance, Prevention, and Control of Taeniasis/Cysticercosis. WHO/VPH/83.49: World Health Organization; 1983.

38. Roman G., et al. A proposal to declare neurocysticercosis an international reportable disease. Bull World Health Organ. 2000;78(3):399-406.

39. Goodman K.A., Ballagh S.A., Carpio A. Case–control study of seropositivity for cysticercosis in Cuenca, Ecuador. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1999;60(1):70-74.

40. Pawlowsky Z. Taenia solium: basic biology and transmission. In: Singh G., Prabhakar S. Taenia solium Cysticercosis: from Basic to Clinical Science. Wallinword, UK: CABI Publishing; 2002:1-23.

41. Del Brutto O.H. [Neurocysticercosis: up-dating in diagnosis and treatment]. Neurologia. 2005;20(8):412-418.

42. Ellison D., Love S., Chimelli L., et al. Parasitic infections of the CNS. In: Ellison D., Love S. eds. Neuropathology: A Reference Text of CNS Pathology. St. Louis: Mosby; 2004:367-389.

43. Alarcon F. Neurocysticercosis: its aetiopathogenesis, clinical manifestations, diagnosis and treatment. Rev Neurol. 2006;43(Suppl 1):S93-S100.

44. Sotelo J., Marin C. Hydrocephalus secondary to cysticercotic arachnoiditis. A long-term follow-up review of 92 cases. J Neurosurg. 1987;66(5):686-689.

45. Colli B.O., et al. Surgical treatment of cerebral cysticercosis: long-term results and prognostic factors. Neurosurg Focus. 2002;12(6):e3.

46. Perez-Lopez C., et al. Update in neurocysticercosis treatment. Rev Neurol. 2003;36(9):805-811.

47. Aguilar-Rebolledo F. Perfil de la neurocisticercosis en niños mexicanos. Cir Ciruj. 1998;66:89-98.

48. Del Brutto O.H., et al. Proposed diagnostic criteria for neurocysticercosis. Neurology. 2001;57(2):177-183.

49. Sanchez A.L., et al. A population-based, case-control study of Taenia solium taeniasis and cysticercosis. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1999;93(3):247-258.

50. Rosas N., Sotelo J., Nieto D. ELISA in the diagnosis of neurocysticercosis. Arch Neurol. 1986;43(4):353-356.

51. Cotero C., Dávalos Morales E. Epidemiología SNVE (Secretaría de Salud, México). 2004;16(21):1-3.

52. Graham D., Lantos P., Greenfield’s Neuropathology, Oxford: Hodder Arnold Publishers, 2002:vol. 2

53. Rossi N., et al. Inmunodiagnostico de la neurocisticercosis: estudio comparativo de extractos antigénicos de Cysticercus cellulosae y Taenia crassiceps. Rev Cubana Med Trop. 2000;52(3):157-164.

54. Ordoñez G., Medina M., Sotelo J. Immunoblot análisis of serum and CSF from patients with various forms of neurocysticercosis. Neurol Infect Epidemiol. 1996;1:57-61.

55. Ramos-Kuri M., et al. Immunodiagnosis of neurocysticercosis. Disappointing performance of serology (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) in an unbiased sample of neurological patients. Arch Neurol. 1992;49(6):633-636.

56. Suss R.A., Maravilla K.R., Thompson J. MR imaging of intracranial cysticercosis: comparison with CT and anatomopathologic features. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1986;7(2):235-242.

57. Del Brutto O.H., et al. Single-day praziquantel versus 1-week albendazole for neurocysticercosis. Neurology. 1999;52(5):1079-1081.

58. Corona T., et al. Single-day praziquantel therapy for neurocysticercosis. N Engl J Med. 1996;334(2):125.

59. Garcia H.H., et al. Albendazole therapy for neurocysticercosis: a prospective double-blind trial comparing 7 versus 14 days of treatment. Cysticercosis Working Group in Peru. Neurology. 1997;48(5):1421-1427.

60. Diazgranados-Sanchez J.A., et al. [Ivermectin as a therapeutic alternative in neurocysticercosis that is resistant to conventional pharmacological treatment]. Rev Neurol. 2008;46(11):671-674.

61. Salinas R., Prasad K. Drugs for treating neurocysticercosis (tapeworm infection of the brain). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (2):2000. CD000215

62. Del Brutto O.H. Prognostic factors for seizure recurrence after withdrawal of antiepileptic drugs in patients with neurocysticercosis. Neurology. 1994;44(9):1706-1709.

63. Perneczky A., Reisch R., Key Hole Approaches in Neurosurgery, vol. 1;New York, Springer-Verlag Wien, 2008.

64. Gimenez-Roldan S., Diaz F., Esquivel A. [Neurocysticercosis and immigration]. Neurologia. 18(7), 2003. 385–358