Management of labour

Stages of labour

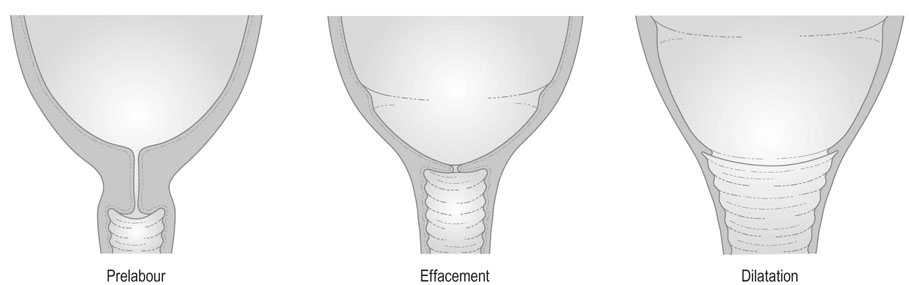

• The first stage commences with the onset of regular painful contractions and cervical changes until it reaches full dilatation and is no longer palpable. The first stage is divided into an early latent phase when the cervix becomes effaced and shorter from 3 cm in length and dilates up to 3 cm, and an active phase when the cervix dilates from 3 cm to full dilatation or 10 cm.

• The second stage is the duration from full cervical dilatation to delivery of the fetus. This is subdivided into a pelvic or passive phase when the head descends down the pelvis, and an active phase when the mother gets a stronger urge to push and the fetus is delivered with the force of the uterine contractions and the maternal bearing down effort.

• The third stage is the duration from the delivery of the new born to delivery of the placenta and membranes.

Onset of labour

The clinical signs of the onset of labour are:

• Regular, painful contractions that increase in frequency and duration and that produce progressive cervical dilatation.

• The passage of blood-stained mucus from the cervix called the ‘show’ is associated with but not on its own an indicator of the onset of labour.

• Similarly, rupture of the fetal membranes can be at the onset of labour, but this is variable and may occur without uterine contractions. If the latent period between rupture of membranes (ROM) to onset of painful uterine contractions is greater than 4 hours it is called prelabour rupture of membranes (PROM) and this can occur at term or in the preterm period when it is called preterm prelabour rupture of membranes (PPROM).

The initiation of labour

• The uterine myocytes contract and shorten, unlike the process in striated muscle, where cells contract but then return to their precontraction length.

• Ion channels within the myometrium influence the influx of calcium ions into the myocytes and promote contraction of the myometrial cells.

• Other hormones produced in the placenta directly or indirectly influence myometrial contractility, e.g. relaxin, activin A, follistatin, human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) and CRH, by influencing the production of cyclic AMP that causes relaxation of myometrial cells.

The integrity of the cervix is essential to retain the products of conception. It contains myocytes and fibroblasts, and towards term becomes soft and stretchable due to an increase in leucocyte infiltration and a decrease in the amount of collagen with the increase in proteolytic enzyme activity. Increased production of hyaluronic acid reduces the affinity of fibronectin for collagen. The affinity of hyaluronic acid for water causes the cervix to become soft and stretchable, i.e. ripening of the cervix.

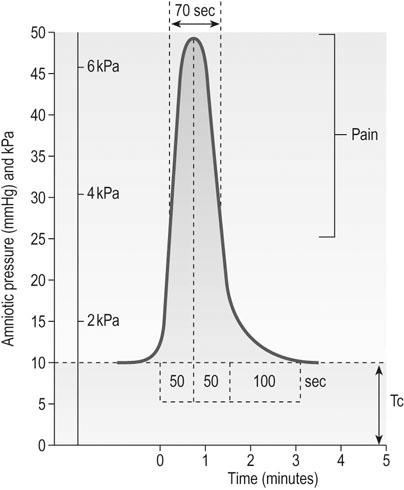

Uterine activity in labour: the powers

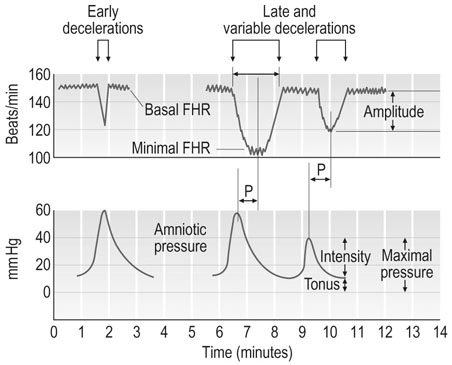

The uterus exhibits infrequent, low-intensity contractions throughout pregnancy. As full term approaches, uterine activity increases in frequency, duration and strength of contractions. By palpation or external tocography one can identify the frequency and duration of contractions, but intrauterine pressure catheters are needed to assess the strength of contractions. It is likely that labour is established if two contractions each lasting for >20 seconds are observed in 10 minutes. Normal resting tonus in labour starts at around 10–20 mmHg and increases slightly during the course of labour (Fig 11.1). Contractions increase in intensity with progress of labour which in some ways are characterized by the duration of contractions. WHO recommends contraction recording on the partograph based on the frequency and duration of contractions.

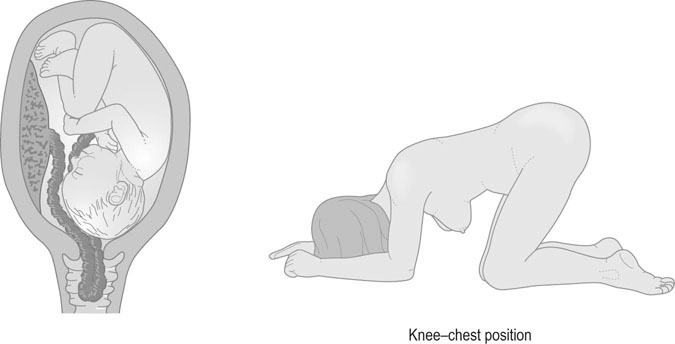

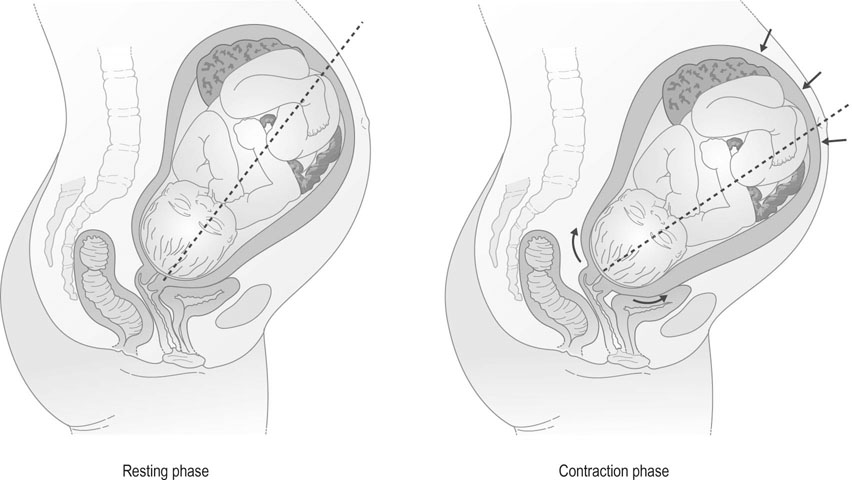

Progressive uterine contractions cause effacement and dilatation of the cervix as the result of shortening of myometrial fibres in the upper uterine segment and stretching and thinning of the lower uterine segment (Fig. 11.2). This process is known as retraction. The lower segment becomes elongated and thinned as labour progresses and the junction between the upper and lower segment rises in the abdomen. Where labour becomes obstructed, the junction of the upper and lower segments may become visible at the level of the umbilicus; this is known as a retraction ring (also known as Bandl’s ring).

The realignment of the uterine axis promotes descent of the presenting part as the fetus is pushed directly downwards into the pelvic cavity (Fig. 11.3).

The passages

The shape and structure of the bony pelvis has already been described (see Chapter 6). The size and shape of the pelvis vary from woman to woman and not all women have a gynaecoid pelvis; some may have platypelloid, anthropoid or android pelvis thus influencing the outcome of labour. Softening of the sacroiliac ligaments and the pubic symphysis allow expansion of the pelvic cavity, and this feature along with the dynamic changes of the head diameter brought about by flexion, rotation and moulding facilitate normal progress and spontaneous vaginal delivery.

The mechanism of labour

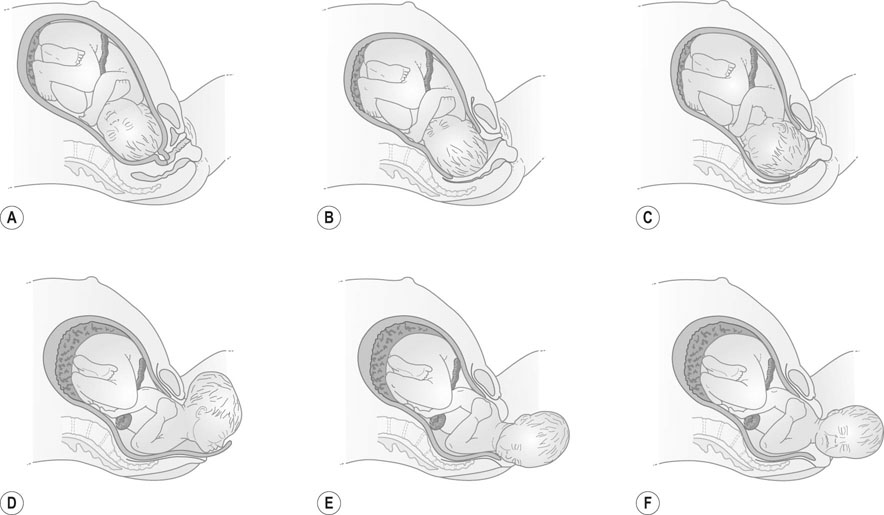

The process of normal labour therefore involves the adaptation of the fetal head to the various segments and diameters of the maternal pelvis and the following processes occur (Fig. 11.4):

1. Descent occurs throughout labour and is both a feature and a prerequisite for the birth of the baby. Engagement of the head normally occurs before the onset of labour in the majority of primigravid woman, but may not occur until labour is well established in a multipara. Descent of the head provides a measure of the progress of labour.

2. Flexion of the head occurs as it descends and meets the medially and forward sloping pelvic floor, bringing the chin into contact with the fetal thorax. Flexion produces a smaller diameter of presentation, changing from the occipito-frontal diameter, when the head is deflexed, to the suboccipitobregmatic diameter when the head is fully flexed.

3. Internal rotation: The head rotates as it reaches the pelvic floor and the occiput normally rotates anteriorly from the lateral position towards the pubic symphysis. This is due to the force of contractions being transmitted via the fetal spine to the head at the point the spine meets the skull which is more posterior and due to the medially and forward sloping pelvic floor. Occasionally, it rotates posteriorly towards the hollow of the sacrum and the head may then deliver as a face–to–pubis delivery.

4. Extension: The acutely flexed head descends to distend the pelvic floor and the vulva, and the base of the occiput comes into contact with the inferior rami of the pubis. The head now extends until it is delivered. Maximal distension of the perineum and introitus accompanies the final expulsion of the head, a process that is known as ‘crowning’ when the head is seen at the introitus but does not recede in between contractions.

5. Restitution: Following delivery of the head, it rotates back to be in line with its normal relationship to the fetal shoulders. The direction of the occiput following restitution points to the position of the vertex before the delivery.

6. External rotation: When the shoulders reach the pelvic floor, they rotate into the anteroposterior diameter of the pelvis. This is accompanied by rotation of the fetal head so that the face looks laterally at the maternal thigh.

7. Delivery of the shoulders: Final expulsion of the trunk occurs following delivery of the shoulders. The anterior shoulder is delivered first by traction posteriorly on the fetal head so that the shoulder emerges under the pubic arch. The posterior shoulder is delivered by lifting the head anteriorly over the perineum and this is followed by rapid delivery of the remainder of the trunk and the lower limbs.

The third stage of labour

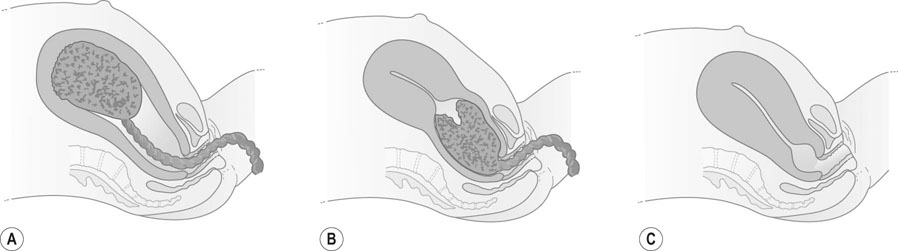

The third stage of labour starts with the completed expulsion of the baby and ends with the delivery of the placenta and membranes (Fig. 11.5).

The management of normal labour

Examination at the commencement of labour

On admission, the following examination should be performed:

• Full general examination, including temperature, pulse, respiration, blood pressure and state of hydration; the urine should be tested for glucose, ketone bodies and protein.

• Obstetrical examination of the abdomen: Inspection is followed by palpation to determine the fetal lie, presentation and position, and the station of the presenting part by estimating fifths of head palpable. Auscultation of the fetal heartbeat is by a stethoscope or by using a Doptone device which enables the mother and her partner to hear.

• Vaginal examination in labour should be performed only after cleansing of the vulva and introitus and using an aseptic technique with sterile gloves and an antiseptic cream. Once the examination is started, the fingers should not be withdrawn from the vagina until the examination is completed.

The following factors should be noted:

• The position, consistency, effacement and dilatation of the cervix.

• Whether the membranes are intact or ruptured and, if ruptured, the colour and quantity of the amniotic fluid.

• The fetal presentation (e.g. vertex, breech), position (e.g. LOA, ROA, ROP, etc.) of the presenting part and its relationship to the level of the ischial spines (e.g. station −1 or +1 etc.).

In vertex presentation the degree of caput (soft tissue scalp swelling), moulding (0, +1. +2 and +3) and synclitism (sagittal suture bisects the pelvis) should be noted.

General principles of the management of the first stage of labour

The guiding principles of management are:

• Observation of the progress of labour and intervention if it is slow.

• Monitoring the fetal and maternal condition.

• Pain relief during labour and emotional support for the mother.

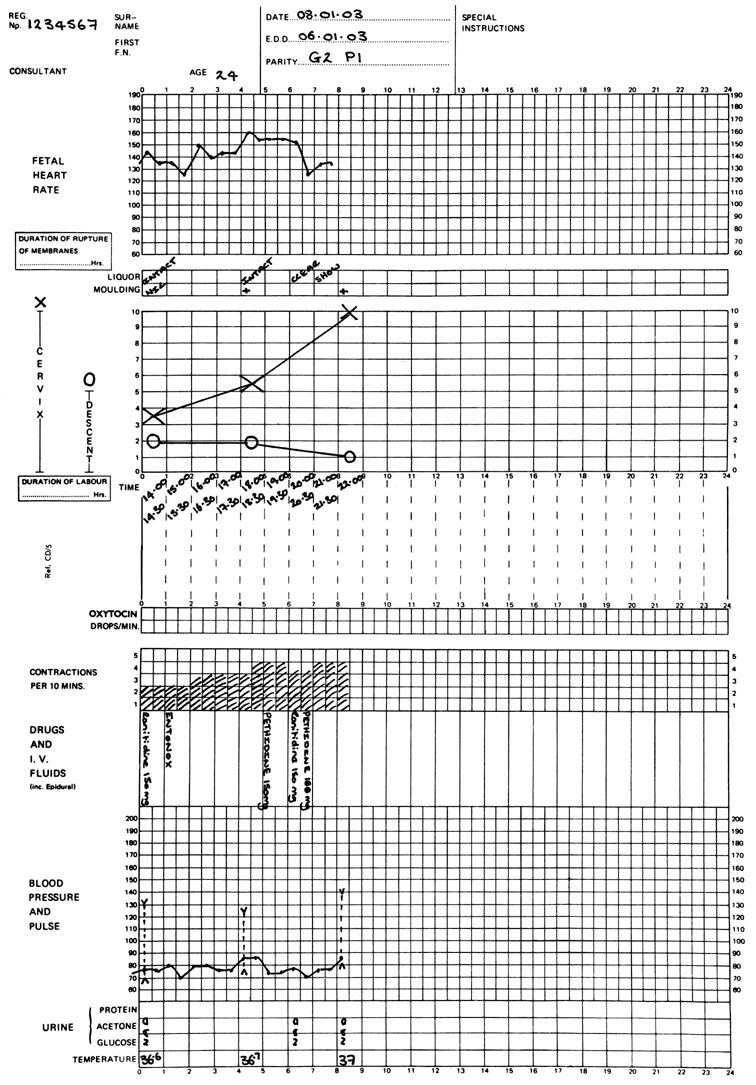

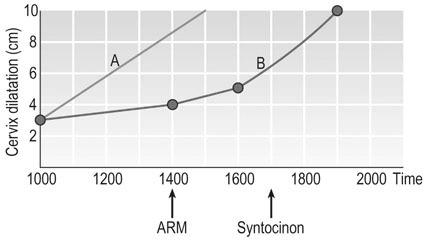

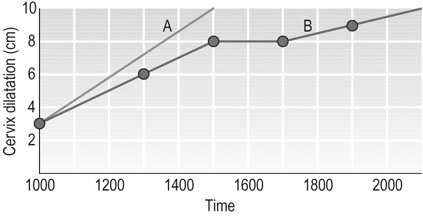

Observation: the use of the partogram

The introduction of graphic records of progress of cervical dilatation and descent of the head was a major advance in the management of labour. It enables the early recognition of a labour that is non-progressive. The partogram (Fig. 11.6) is a single sheet of paper on which there is a graphic representation of progress in labour. On the same sheet other observations related to labour can be entered. There are sections to enter the frequency and duration of contractions, fetal heart rate (FHR), colour of liquor, caput and moulding, station or descent of the head, maternal heart rate, BP and temperature. The partogram should be started as soon as the mother is admitted to the delivery suite and this is recorded as zero time regardless of the time at which contractions started. However, the point of entry on to the partogram depends on a vaginal assessment at the time of admission to the delivery suite. The value of this type of record system is that it draws attention visually to any aberration from normal progress in labour.

Pain relief in labour

Regional analgesia

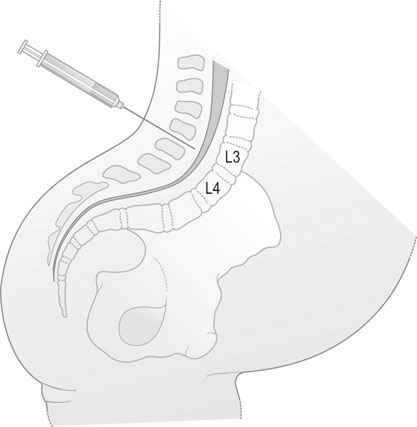

A fine catheter is introduced into the lumbar epidural space and a local anaesthetic agent such as bupivacaine is injected (Fig. 11.7). The addition of an opioid to the local anaesthetic greatly reduces the dose requirement of bupivacaine, thus sparing the motor fibres to the lower limbs and reducing the classic complications of hypotension and abnormal fetal heart rate.

• Insertion of an intravenous cannula and preloading with no more than 500 mL of saline or Hartmann’s solution.

• Insertion of the epidural cannula at the L3–L4 interspace and injection of the local anaesthetic agent at the minimum dose required for effective pain relief.

• Monitor blood pressure, pulse rate and fetal heart rate and adjust maternal posture to achieve the desired analgesic effect.

The complications of epidural analgesia include:

• Hypotension: this can be avoided by preloading and the use of low-dose anaesthetic agents and opioid solutions.

• Accidental dural puncture: occurs in fewer than 1% of epidurals.

• Postdural headache: about 70% of mothers will develop a headache if a 16 or 18 gauge needle is used. A postdural headache that persists for more than 24 hours should be treated with an epidural blood patch.

Contraindications to regional anaesthesia include:

Other forms of regional anaesthesia

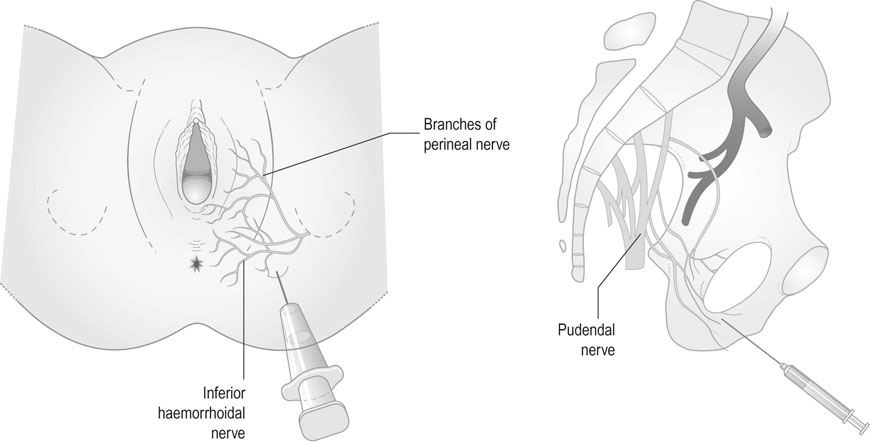

Pudendal nerve blockade involves infiltration around the pudendal nerve as it leaves the pudendal canal and the inferior haemorrhoidal nerve (Fig. 11.8). It was a widely used form of local anaesthesia for operative vaginal deliveries in the past but is now less frequently used as it has been replaced by epidural anaesthesia.

Fetal monitoring

Intermittent auscultation

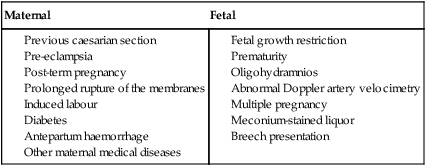

The clinical guidelines for the use of electronic fetal monitoring have been produced by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists in the UK and Australia and New Zealand and by similar bodies in USA and Canada as well as by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence in the UK. They have great similarities and minor differences that are unlikely to influence clinical outcome. Admission cardiotocogram or routine CTG using electronic monitoring is not recommended for women classified as low risk. The specific indications for continuous electronic fetal monitoring are listed in Table 11.1.

Fetal cardiotocography

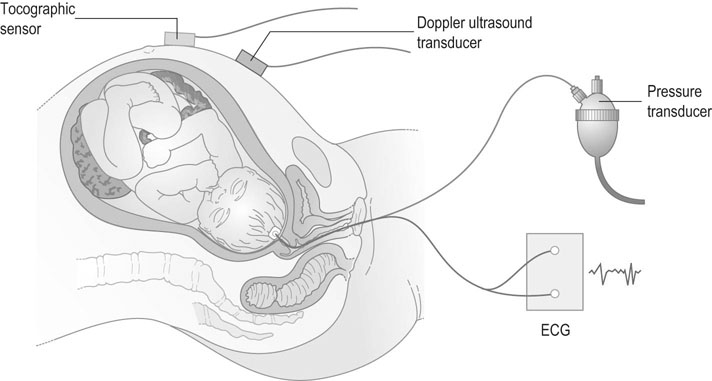

Uterine activity is recorded either with a pressure transducer applied over the anterior abdominal wall between the fundus and the umbilicus or by inserting a fluid-filled catheter or a pressure sensor into the uterine cavity through the cervical canal (Fig. 11.9). External tocography gives an accurate measurement of the frequency and duration but only relative information of intrauterine pressure. Accurate measurements of pressure needs an intrauterine catheter or transducer and is not used as a routine in most centres due to lack of evidence of its clinical benefit.

Basal heart rate

The definition of normality in the pattern of the fetal heart rate is easier than defining what is abnormal. The normal heart rate varies between 110 and 160 beats/min (Fig. 11.10). A rate faster than 160 is defined as fetal tachycardia and a rate less than 110 is fetal bradycardia.

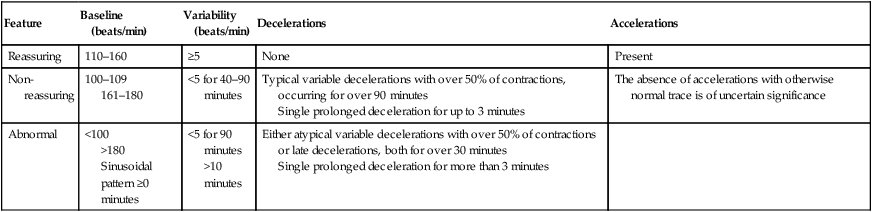

Transient changes in fetal heart rate (Tables 11.2 and 11.3)

Accelerations

Table 11.2

Classification of FHR trace features

| Feature | Baseline (beats/min) | Variability (beats/min) | Decelerations | Accelerations |

| Reassuring | 110–160 | ≥5 | None | Present |

| Non-reassuring | 100–109 161–180 |

<5 for 40–90 minutes | Typical variable decelerations with over 50% of contractions, occurring for over 90 minutes Single prolonged deceleration for up to 3 minutes |

The absence of accelerations with otherwise normal trace is of uncertain significance |

| Abnormal | <100 >180 Sinusoidal pattern ≥0 minutes |

<5 for 90 minutes >10 minutes |

Either atypical variable decelerations with over 50% of contractions or late decelerations, both for over 30 minutes Single prolonged deceleration for more than 3 minutes |

Table 11.3

Definition of normal, suspicious and pathological FHR traces and recommended actions

| Category | Definition | Action |

| Normal | An FHR trace in which all four features are classified as reassuring | Continue intermittent or continuous monitoring as indicated by risk factors |

| Suspicious | An FHR trace with one feature classified as non-reassuring and the remaining features classified as reassuring | Exclude factors indicating need for immediate delivery (cord prolapse, uterine rupture, abruption). Treat dehydration, hyperstimulation, hypotension and change position. Continue CTG |

| Pathological | An FHR trace with two or more features classified as non-reassuring or one or more classified as abnormal | Exclude factors indicating need for immediate delivery (cord prolapse, uterine rupture, abruption). Treat dehydration, hyperstimulation and change position. Deliver if prolonged bradycardia. Either obtain further information on fetal status by fetal blood scalp sampling or deliver. |

Preterm delivery

Spontaneous preterm labour

Aetiology

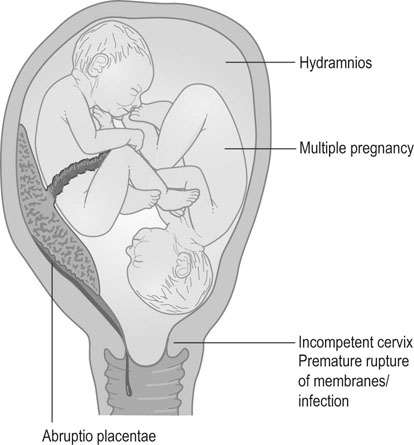

Some of the major factors associated with the preterm labour are shown in Figure 11.11. There is an association with poor social conditions and nutritional status and also with antepartum haemorrhage, multiple pregnancy, uterine anomalies, cervical incompetence and PROM, which is often associated with infection. A previous history of preterm delivery is the best single predictor. The relative risk is about 3 and the risk increases if there has been more than one preterm delivery. Complications during a pregnancy may also precipitate preterm labour; this includes over distension of the uterus, such as multiple pregnancy and hydramnios. Other factors, such as haemorrhage in either the first or early second trimester, increase the risk of subsequent preterm labour. Severe maternal illness, particularly febrile illness, may also promote the early onset of labour.

Social factors involve maternal age (under 20 or over 35 years), primiparity, ethnicity, marital status, cigarette smoking, substance abuse and heavy, stressful work (Box 11.1). Active social intervention appeared to reduce the incidence of preterm labour in early studies but has not received unanimous support due to lack of good scientific evidence.

The preterm infant

Survival

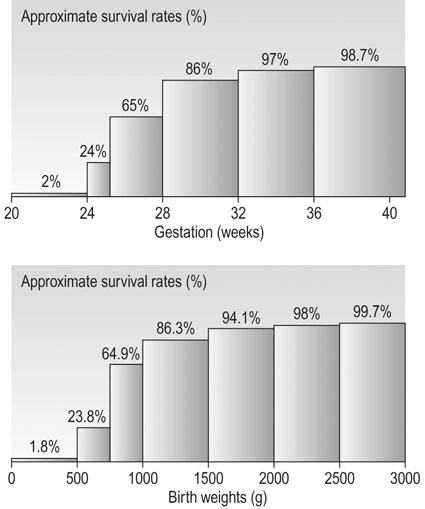

If the cause is of infective origin it may affect the mother but the effect is predominantly on the fetus. Improvements in neonatal services provide good chance of intact survival if the new born is in good condition and is of reasonable birth weight. Each day of delay in birth after 24 weeks increases the chance of survival by 3–6%, and hence the need to conserve the pregnancy as long as possible. An infant born with a birth weight of less than 500 g has little chance of survival whereas one born weighing 1500 g is nearly as likely to survive as a full-term infant. Between 500 and 1000 g, every 100 g increment produces a significant increase in survival (Fig. 11.12). The major causes of death in very-low-birth weight infants are infection, respiratory distress syndrome, necrotizing enterocolitis and periventricular haemorrhage.

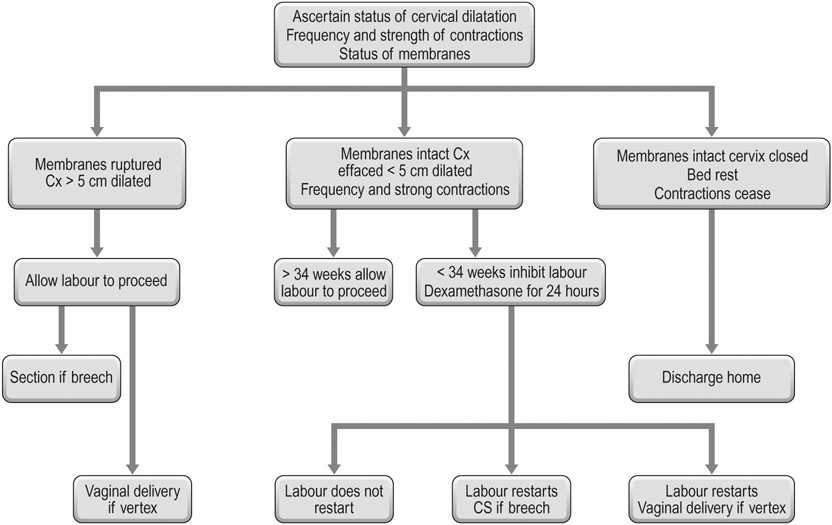

The management of preterm labour

Treatment

Once the woman is admitted to hospital in established preterm labour, a decision must be made as to the approach to management. The long-term advantages of preventing preterm labour are uncertain, although every day of delay in the early preterm period increases the chance of survival and reduces morbidity and more dependence on intensive care. There is no controversy in postponing delivery long enough for the administration of corticosteroids to enable the production of fetal lung surfactant with the aim of reducing the chance of hyaline membrane disease (HMD) and respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) (Fig. 11.13).

Drug therapy to delay the delivery can be divided into groups operating on different principles (Box 11.2).

β-Adrenergic agonists

The most commonly used drugs are ritodrine, salbutamol and terbutaline. The drugs should not be used where there is a known history of cardiovascular disease and hypertension.

The dosage can be reduced slowly after the administration of corticosteroids to the mother. It is unlikely that any major benefit will accrue to the fetus if the gestational age exceeds 34 weeks. It is necessary to continue treatment till the mother is transferred to a tertiary care centre with neonatal intensive care facilities. Oral maintenance therapy remains unproven and is not recommended.

Prelabour rupture of the membranes

• The tensile strength of the fetal membranes, which may be weakened by infection.

• The support of the surrounding tissues, which is reflected in the dilatation of the cervix; the greater the dilatation of the cervix, the greater the likelihood that the membranes will rupture.

Management

If there is a positive culture or evidence of maternal infection, the appropriate antibiotic should be administered. If there is evidence of infection, labour should be induced using an oxytocic infusion and delivery expected in the interest of the fetus and the mother. If there is no evidence of infection, conservative management with erythromycin cover should be adopted. Tocolysis is generally ineffective in the presence of ruptured membranes if contractions are already well established and one should consider whether the underlying triggering factor may be infection. If gestation is over 28 weeks the infant probably has a better chance of survival if delivered. Most women with PROM will deliver spontaneously within 48 hours.

Induction of labour

Indications

The major indications for induction of labour are:

• prolonged pregnancy (in excess of 42 weeks gestation)

• placental insufficiency and intrauterine growth restriction

• antepartum haemorrhage: placental abruption and antepartum haemorrhage of uncertain origin

Prolonged pregnancy is defined as pregnancy exceeding 294 days from the first day of the last menstrual period in a woman with a 28-day cycle. The perinatal mortality rate doubles after 42 weeks and trebles after 43 weeks compared with 40 weeks gestation. Although, routine induction of labour has a minimal effect on the overall perinatal mortality rate, it is offered after 41+ weeks as an adverse outcome is not an acceptable option for the individual mother. Conservative management of prolonged pregnancy is preferred by some and it involves at least twice weekly monitoring of the fetus with ultrasound assessment of liquor volume and non-stress test (NST) or antenatal CTG. Induction is undertaken if there is suspicion of fetoplacental compromise. However, many women request induction of labour on the basis of the physical discomfort of the continuing pregnancy. The chance of successful vaginal delivery should be considered and explained to the mother based on parity and cervical score. Artificial separation of membranes just past 40 weeks reduces the number who may need induction after 41 weeks.

Methods of induction

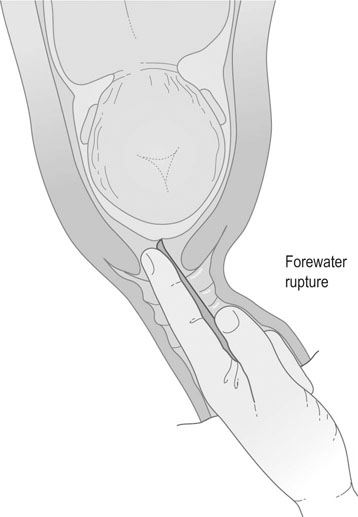

Forewater rupture

Rupture of the membranes should be performed under conditions of full asepsis in the delivery suite. Under ideal circumstances, the cervix should be soft, effaced and at least 2 cm dilated. The head should be presenting by the vertex and should be engaged in the pelvis. In practice, these conditions are often not fulfilled, and the degree to which they are adhered to depends on the urgency of the need to start labour. The mother is placed in the supine or lithotomy position and, after swabbing and draping the vulva, a finger is introduced through the cervix, and the fetal membranes are separated from the lower segment: a process known as ‘stripping the membranes’. The bulging membranes are then ruptured with Kocher’s forceps, Gelder’s forewater amniotomy forceps or an amniotomy hook (Fig. 11.14). The amniotic fluid is released slowly and care is taken to exclude presentation or prolapse of the cord. The fetal heart rate should be monitored for 30 minutes before and following rupture of the membranes.

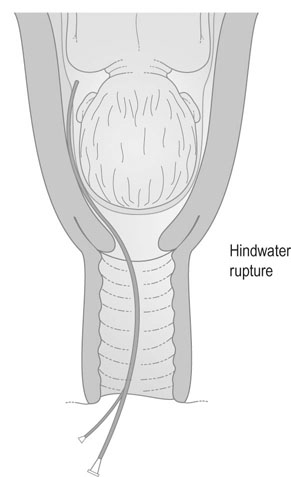

Hindwater rupture

An alternative method of surgical induction involves rupture of the membranes behind the presenting part. This is known as hindwater rupture. A sigmoid-shaped metal cannula known as the Drewe–Smythe catheter is introduced through the cervix and penetrates the membranes behind the presenting part (Fig. 11.15). The theoretical advantage of this technique is that it reduces the risk of prolapsed cord. In reality, the risk is even lower with forewater rupture than with spontaneous rupture of the membranes, and the technique of hindwater rupture is now rarely used.

Medical induction of labour following amniotomy

The principal hazards of combined surgical and medical induction of labour are:

• Hyperstimulation: Excessive or too frequent and prolonged uterine contractions reduce uterine blood flow and result in fetal asphyxia, i.e. contractions should not occur more frequently than every 2 minutes and should not last in excess of 1 minute. The Syntocinon infusion should be discontinued if excessive uterine activity occurs or if there are signs of pathological FHR pattern of concern.

• Prolapse of the cord: This should be excluded by examination at the time of forewater rupture, or subsequently if severe variable decelerations occur on the FHR trace.

• Infection: A prolonged induction–delivery interval increases the risk of infection in the amniotic sac with consequent risks to both infant and mother. If the liquor becomes offensive and/or maternal pyrexia occurs, the labour should be terminated unless the delivery is imminent and the infant delivered.

Medical induction of labour and cervical ripening

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommends the use of prostaglandins for all inductions of labour including when the cervix is favourable.

Prostaglandins

• Orally: Doses of 0.5 mg are increased to 2 mg/h until contractions are produced. However this is not used in current practice due to the side effects of vomiting and diarrhoea.

• By the vaginal route: The most commonly used method is to insert prostaglandin pessaries or xylose gel into the posterior fornix. Nulliparous women with an unfavourable cervix (Bishop’s score of less than 4) are given an initial dose of 2 mg gel and multiparous women and nulliparae with a Bishop’s score of more than 4 an initial dose of 1 mg. This is repeated if necessary after 6 hours and again the following day up to a maximum dose of 4 mg until labour is established or the membranes can be ruptured and the induction continued with oxytocin. The pessaries come as 3 mg doses. If there is no response to the first pessary in 6 hours in the form of regular contractions or cervical changes, a second pessary is inserted. If the mother does not start labour or there is no cervical change another pessary is inserted the next day.

The recent WHO (2011) guidelines on induction of labour recommend oral misoprostol 25 µg every 2 to 4 hours. Misoprostol (prostaglandin E1) is not licensed in many countries for use in obstetrics, and the 25 or 50 µg formulations are not available so a 200 µg formulation needs to be divided or dissolved and the appropriate dose taken. The use of prostaglandins is contraindicated in the presence of a previous uterine scar. Some use the prostaglandin E2 pessaries or gel with caution but not prostaglandin E1 as there is increased incidence of uterine rupture that will compromise the fetus and the mother. The mother should be properly counselled before these drugs are used.

Inefficient uterine activity

Management

The general principles of management of abnormal uterine activity involve:

• Adequate pain relief, particularly in the presence of hypertonic uterine inertia and principally with epidural analgesia.

• Adequate fluid replacement by intravenous infusion of dextrose saline or Hartmann’s solution.

• Stimulation of coordinated uterine activity using a dilute infusion of oxytocin.

In the presence of hypotonic uterine inertia, uterine activity may be stimulated by encouraging mobilization of the mother and, if the membranes are intact, by artificial rupture of the membranes; an oxytocic infusion will also usually stimulate labour and delivery.

Cord presentation and cord prolapse

Cord presentation (Fig. 11.18) occurs when any part of the cord lies alongside or in front of the presenting part. The diagnosis is usually established by digital palpation of the pulsating cord, which may be felt through the intact membranes. When the membranes rupture, the cord prolapses and may appear at the vulva or be palpable in front of the presenting part.