Chapter 43 Management of Exacerbations in Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease

Epidemiology

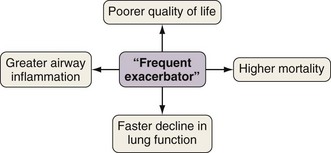

Exacerbations generally become both more frequent and more severe as the severity of the underlying COPD progresses. On average, patients with moderate to severe COPD, typical of those attending secondary care, will have one or two exacerbations requiring additional treatment annually. However, annual exacerbation incidence rates differ greatly among individual patients, and those prone to more frequent exacerbations experience a particular burden of disease (Figure 43-1). The best determinant of future exacerbation history is past exacerbation frequency, such that some patients appear more intrinsically susceptible and some more resistant to these important events.

Pathophysiology

Defining the role of airway infection in causing COPD exacerbation is problematic. Recent advances in molecular biology have isolated respiratory viruses and potentially pathogenic bacteria from the airways of most patients during exacerbations (Box 43-1). However, certainly for patients with more severe underlying disease, bacteria also are often present in the stable state (bacterial colonization). Therefore the presence of an organism at exacerbation does not assume a role in causing that exacerbation. More recent studies suggest that a change in the colonizing bacterial strain may be the precipitating cause. However, not all strain changes are associated with exacerbation, and vice versa. Reflecting this, as discussed later, antibiotics are not of universal benefit during exacerbations. Rhinovirus is the most often identified viral pathogen, and thus exacerbations are more common during the winter months, when viral circulation in the community is higher. The role of atypical organisms such as Chlamydia and Mycoplasma species appears minimal.

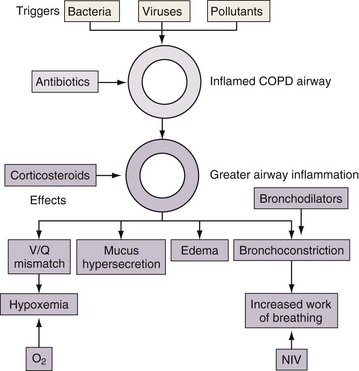

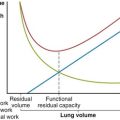

Understanding the pathophysiology of exacerbations in COPD explains the rationale for the various therapies employed. Bronchodilators may be helpful for increased bronchoconstriction and hyperinflation, corticosteroids may reduce airway inflammation, and antibiotics may be appropriate in exacerbations caused by bacteria (Figure 43-2).

Diagnosis

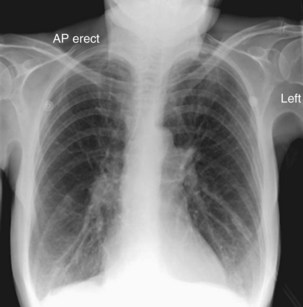

Although investigations are not helpful in the diagnosis of exacerbation, diagnostic tests help assess the severity of the presentation and exclude other conditions in patients with underlying COPD that may mimic or complicate exacerbation. Such diagnoses include pneumonia, pneumothorax, pulmonary embolus, and cardiac failure, and appropriate investigations include chest radiography, electrocardiography, oxygen saturation (SaO2) values, and arterial blood gas (ABG) analysis. Simple venous blood tests include complete blood count, urea and electrolytes, and C-reactive protein. A typical chest radiograph at exacerbation (Figure 43-3) should appear much the same as the patient’s radiograph in the stable state. Spirometry is not generally helpful because absolute values may be misleading, changes at exacerbation are small, and patients acutely dyspneic have difficulty performing the maneuvers. Sputum microscopy and culture may help to refine empirical antibiotic therapy in those not initially improving. For the patient with mild exacerbation responding to an increase in inhaled bronchodilators, it may be appropriate to omit further investigation.

Treatment

Pharmacotherapy

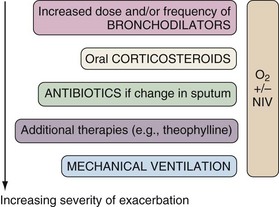

The principles of therapy at the time of COPD exacerbation are twofold: to modify the course of the event and to support the patient’s respiratory function so that disease-modifying therapies can work. Treatment is given in proportion to the clinical severity of the event, and the sequential approach is illustrated in Figure 43-4. Many guidelines exist to guide appropriate therapy, including recently updated evidence-based statements from the UK National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE). Attention to comorbidities is also important, and in the recovery phase the clinician should consider interventions that may reduce the risk of subsequent exacerbations.

Noninvasive Ventilation

However, NIV is not a substitute for invasive ventilation when required. Therefore, the management plan should consider suitability for invasive ventilation should NIV fail, and some patients may have relative contraindications to NIV or can have respiratory failure of such severity that they should be immediately assessed for invasive ventilation (Box 43-2). Most patients suitable for NIV are able to tolerate the treatment (Figure 43-5).

Other Therapies

Methylxanthine drugs such as theophylline have a variety of potentially beneficial effects on respiratory and cardiac function, but a meta-analysis failed to show any benefit in lung function or symptoms with methylxanthines during COPD exacerbations. Despite this and well-recognized problems with drug interactions, side effects, and a narrow therapeutic range necessitating the monitoring of drug levels, theophyllines are still sometimes used in patients who are not demonstrating sufficient progress on otherwise maximal therapy. One action of theophyllines is as phosphodiesterase (PDE) inhibitors, and newer, selective PDE4 inhibitors are currently undergoing trials (see Chapter 42).

Clinical Course and Prevention

Vaccination against influenza and pneumococcus (S. pneumoniae) is recommended.

The finding that exacerbation susceptibility varies among COPD patients means it is particularly important to target exacerbation reduction interventions at those most likely to develop these events. The simplest way is to ask patients how many courses of systemic (antibiotic and corticosteroid) therapy they received for exacerbations over the past 12 months. Patients receiving two or more such courses (“frequent exacerbators”) are likely to remain frequent exacerbators in the future and should be offered all appropriate exacerbation reduction interventions (see Figure 43-1).

Web Resources and Guidelines/Protocols

World Health Organization (WHO) Global Initiative for Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD). www.goldcopd.com.

American Thoracic Society (ATS)/European Respiratory Society (ERS) standards for the diagnosis and treatment of COPD. www.ersnet.org.

United Kingdom National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) COPD guidelines. www.nice.org.uk.

Cochrane Airways Group (up-to-date, accurate systematic reviews and meta-analyses). www.cochrane-airways.ac.uk.

Anthonisen NR, Manfreda J, Warren CP, et al. Antibiotic therapy in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Ann Intern Med. 1987;106:196–204.

Hurst JR, Vestbo J, Anzueto A, et al. Susceptibility to exacerbation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:1128–1138.

Lightowler JV, Wedzicha JA, Elliott MW, et al. Non-invasive positive pressure ventilation to treat respiratory failure resulting from exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2003;326:185–187.

Niewoehner DE, Erbland ML, Deupree RH, et al. Effect of systemic glucocorticoids on exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1941–1947.

Saint S, Bent S, Vittinghoff E, Grady D. Antibiotics in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. A meta-analysis. JAMA. 1995;273:957–960.

Seemungal TAR, Donaldson GC, Bhowmik A, et al. Time course and recovery of exacerbations in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1608–1613.

Sethi S, Evans N, Grant BJB, et al. New strains of bacteria and exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:465–471.

Wedzicha JA, Martinez FJ. Lung biology in health and disease, Vol 228. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations. New York: Informa Healthcare, 2009.