Chapter 38 Management of dental emergencies

There are many kinds of dental emergencies, some of which can be extremely subjective. Whereas a small carious lesion or infected extraction socket may cause excruciating pain for one person, a fractured jaw may be asymptomatic and only discovered as an incidental finding after routine X-rays. Emergency departments in teaching hospitals will nearly always have an accredited on-call dentist or in rural settings may refer all dental emergencies to a local dental emergency service or individual dentist. As dental emergencies are rarely life-threatening, commonsense measures such as antibiotics, sedatives and analgesics where appropriate should get the patient through the night or weekend until an appointment can be arranged for the next working day.

TOOTHACHE

Dental caries

Dental caries may be minor or extensive and may undermine an existing dental restoration or artificial crown.

Erosion or abrasion

Erosion or abrasion areas at the tooth/gum junction may produce extreme hypersensitivity.

INFECTED GUMS

Gingivitis/periodontitis

Poor oral health may lead initially to marginal gingivitis, progressing over many years to moderate or severe periodontitis and associated problems with the bone surrounding the teeth. Advanced periodontal disease may lead to tooth mobility, bad breath, oral bleeding, periodontal abscess formation, extrusion, drifting or exfoliation of teeth and generalised mouth pain. Periodontal disease may be an early clinical clue for systemic diseases such as HIV infection and diabetes or follow treatment in the case of graft versus host disease (GVHD) in bone marrow transplantation and radiation therapy of the head and neck.

MOUTH SORES AND ULCERATION

Oral ulceration and mouth sores may be the result of a myriad of precipitating factors including stress, acidic foods and even specific foods. Sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS), a detergent commonly found in toothpastes, has also been implicated.

FACIAL SWELLINGS

The most common cause of facial swellings is dental abscess formation. A dental abscess is an infection around the root of a tooth or in the gum which causes an accumulation of pus. At this stage there is often associated pain but not necessarily swelling. If the infection is left unchecked, the accumulated pus attempts to drain and will track via the path of least resistance, accumulating further as an intra- or extraoral swelling that may not necessarily be overlying the abscessed tooth. Local lymphadenopathy is common, with marked facial swellings caused by dental abscess formation.

HEART DISEASE AND DENTAL CARE

POST-EXTRACTION INSTRUCTIONS

General advice to the patient

These activities may disturb the healing blood clot.

Immediately after a tooth is extracted, the patient may experience discomfort and notice some swelling. This is normal. The initial healing period typically takes 1–2 weeks, and some swelling and residual bleeding should be expected in the 24 hours following an extraction. It is important not to dislodge the blood clot that forms on the wound. Occasionally, this clot can break down, leaving what is known as a dry socket. This can cause temporary pain and discomfort that will subside as the socket heals through a secondary healing process.

Response/advice

ORAL BLEEDING

Generally warfarin or antiplatelet medications need not be stopped prior to dental extractions or deep cleaning. However, appropriate local measures should be adopted in addition to checking with the patient’s cardiologist, in the case of an underlying cardiovascular disease, or haematologist if the concern is due to a blood dyscrasia. Most patients can be managed in a general dental practice setting and do not need to be admitted to hospital. St Vincent’s Hospital has adopted dental recommendations from the United Kingdom as the basis for new prescribing and formulary guidelines.2

Patients being treated with oral anticoagulant medication who have an international normalisation ratio (INR) below 4.0 may have dental extractions without interruption to their treatment. Local measures, which include suturing and packing the extraction site with absorbable gelatine sponge, are generally sufficient to prevent post-extraction bleeding. However, excessive post-extraction or oral bleeding for other reasons may still occur. The most common cause of post-extraction bleeding for the patient with no known systemic problems is failure to follow instructions from the dentist.

TRAUMATIC INJURIES TO TEETH

Traumatic injuries to teeth can be divided into five categories.

Fracture

Response/advice

If the traumatic injury is the result of a minor accident, provide analgesia if required until the next working day. If, however, the injury is the result of a motor vehicle accident, assault or other significant incident, an OPG X-ray should be taken, if available. Often, undisplaced and asymptomatic fractures of the body of the mandible, ramus, condylar head or coranoid process may be detected with an OPG. With grade 3–5 fractures where there are no other bodily injuries present other than minor local lacerations, provide analgesia until the next working day. Should the patient be admitted or require observation in the emergency department for any length of time, contact the on-call dentist.

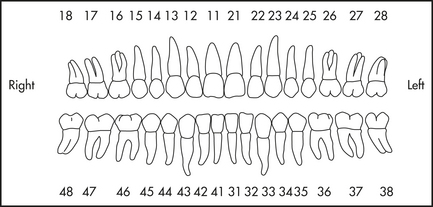

DENTAL NOMENCLATURE

The international numbering system of teeth (Federation Dentaire Internationale—FDI) should be used in any written or verbal communication. The mouth can be divided into four quadrants. In the adult dentition (Figure 38.1) the maxillary right is quadrant 1; the maxillary left, quadrant 2; the mandibular left, quadrant 3; and the mandibular right, quadrant 4. The individual teeth are numbered from the central incisor outwards to the third molar. This provides an easy-to-use two-digit code to indicate the tooth or region of concern. Deciduous or baby teeth follow a similar pattern. The maxillary right is quadrant 5; the maxillary left, quadrant 6; the mandibular left, quadrant 7; and the mandibular right, quadrant 8. The complete deciduous dentition has only five teeth in each quadrant as opposed to eight teeth in each quadrant in the adult dentition.

1 Therapeutic guideline: oral and dental. Version 1. Therapeutic Guidelines Limited; 2007. Also online. Available: http://www.tg.com.au.

2 Online. Available: http://www.ukmi.nhs.uk/med_info/documents/Dental_Patient_on_Warfarin.pdf; http://www.ukmi.nhs.uk/med_info/documents/Dental_Patient_on_Antiplatelet_Medication.pdf.

Copies of information sheets referred to in this chapter are available from mailto:pfoltyn@stvincents.com.au