Management of delivery

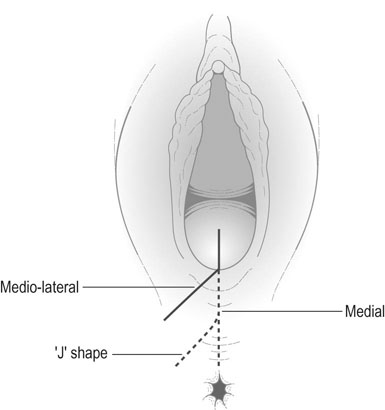

Repair of episiotomy or perineal injury

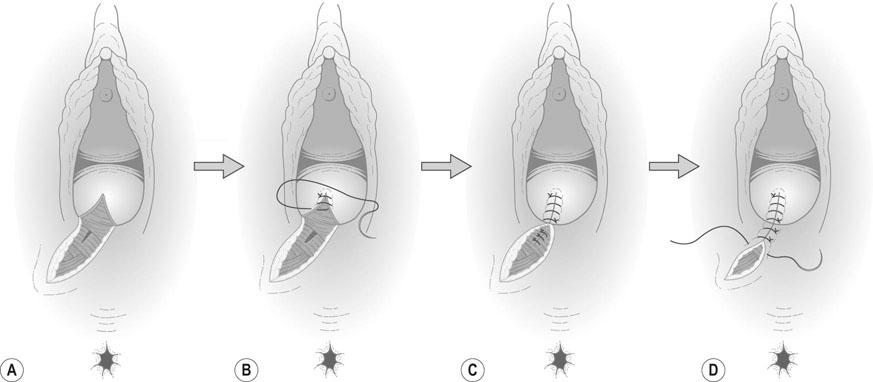

Third and fourth degree injuries

• 3a: less than 50% of the external sphincter is disrupted

• 3b: more than 50% of the external sphincter is disrupted

• 3c: both the external and internal sphincter are disrupted.

Fourth degree tears involve tearing the anal and/or rectal epithelium in addition to sphincter disruption.

A number of risk factors have been identified, though their value in prediction or prevention of sphincter injury is limited (Box 12.1). It is important to examine a perineal injury carefully after delivery so as not to miss sphincter damage. This may increase the rate of sphincter damage, but it will help to reduce the rate of long-term morbidity.

Malpresentations

Breech presentation is discussed in Chapter 8.

Face presentation

Diagnosis

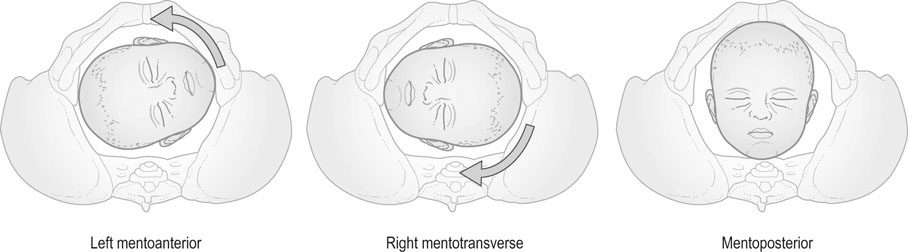

Face presentation is rarely diagnosed antenatally, but is usually identified during labour by vaginal examination when the cervix is sufficiently dilated to allow palpation of the characteristic facial features. However, oedema may develop that may obscure these landmarks. If in doubt, ultrasound will confirm or exclude the diagnosis. The position of a face presentation is defined with the chin as the denominator and is therefore recorded as mentoanterior, mentotransverse and mentoposterior (Fig. 12.5).

Brow presentation

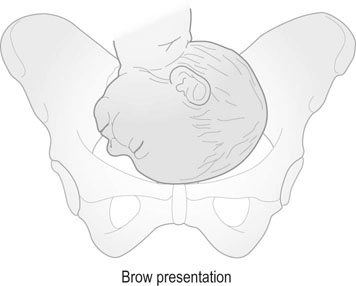

A brow presentation is described when the attitude of the fetal head is midway between a flexed vertex and face presentation (Fig. 12.6) and is the most unfavourable of all cephalic presentations. The condition is rare and occurs in 1 in 1500 births. If the head becomes impacted as a brow the presenting diameter, the mentovertical diameter (13 cm), is incompatible with vaginal delivery.

Malposition of the fetal head

The occipitoposterior position

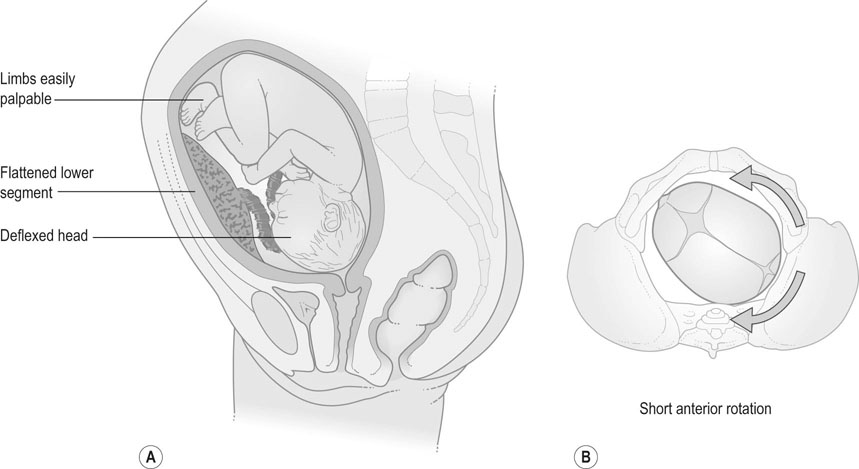

Some 10–20% of all cephalic presentations are OP positions at the onset of labour either as a direct OP or, more commonly, as an oblique right or left OP position. During labour the head usually undertakes the long rotation through the transverse to the OA position but a few, about 5%, remain in the OP position. Where the OP position persists, progress of the labour may be arrested due to the deflexed attitude of the head that results in larger presenting diameters (11.5 cm × 9.5 cm) than are found with OA positions (9.5 cm × 9.5 cm). Prolonged and painful labour associated with backache are characteristic feature of a posterior fetal position (Fig. 12.7).

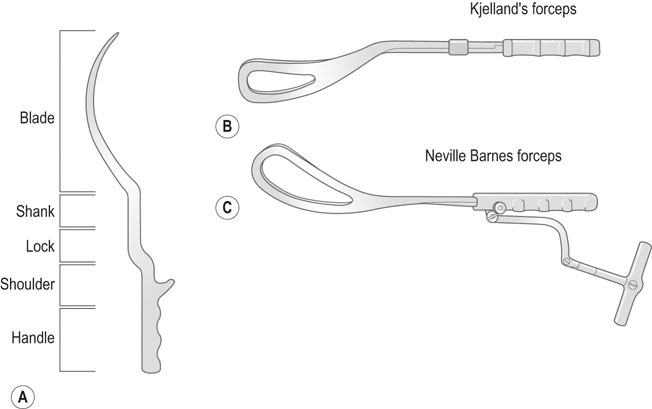

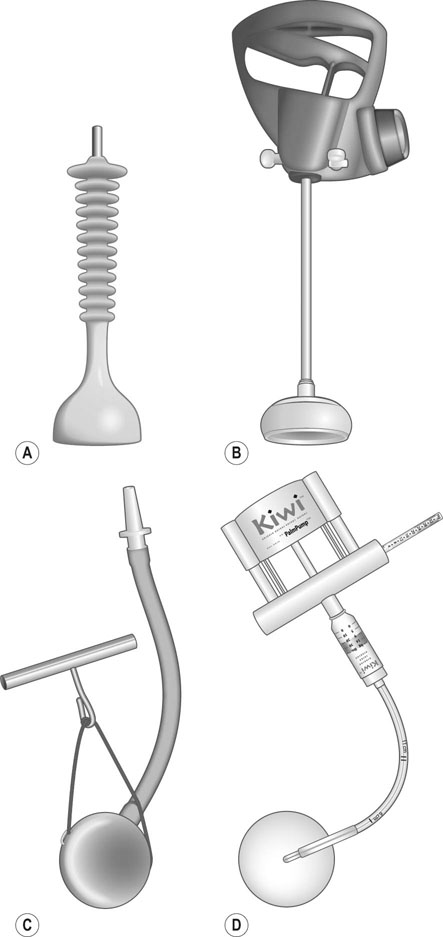

Instrumental delivery

There are two main types of instruments employed for assisted vaginal delivery: the obstetric forceps (Fig. 12.8) and the obstetric vacuum extractor (ventouse; Figure 12.9). The forceps were introduced into obstetric practice some three centuries ago whereas the vacuum extractor as a practical alternative to the forceps only became popular over the past half century.

Indications for instrumental delivery

The common indications for forceps or vacuum assisted delivery are:

Clinical factors that may influence the need for assisted vaginal delivery include the resistance of the pelvic floor and perineum, inefficient uterine contractions, poor maternal expulsive effort, malposition of the fetal head, cephalopelvic disproportion and epidural analgesia.

Method of instrumental delivery

Non-rotational instrumental delivery

Forceps

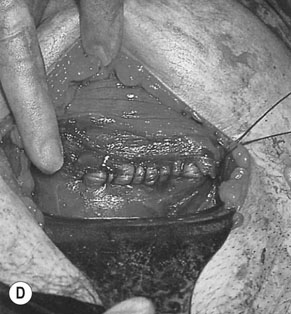

Examples of the types of forceps used when no anterior rotation of the head is required are the Neville Barnes and Simpson’s forceps (Fig. 12.8). Both of these forceps have cephalic and pelvic curves. The two blades of the forceps are designated according to the side of the pelvis to which they are applied. Thus the left blade is applied to the left side of the pelvis (Fig. 12.10A). There is a fixed lock between the blades (Fig. 12.10B). The two sides of the forceps should lock at the shank without difficulty. The sagittal suture should be perpendicular to the shank, the occiput 3–4 cm above the shank and only one finger space between the heel of the blade and the head on either side. Intermittent traction is applied coinciding with the uterine contractions and maternal bearing down efforts in the direction of the pelvic canal (Fig. 12.10C) until the occiput is on view and then the head is delivered by anterior extension (Fig. 12.10D).

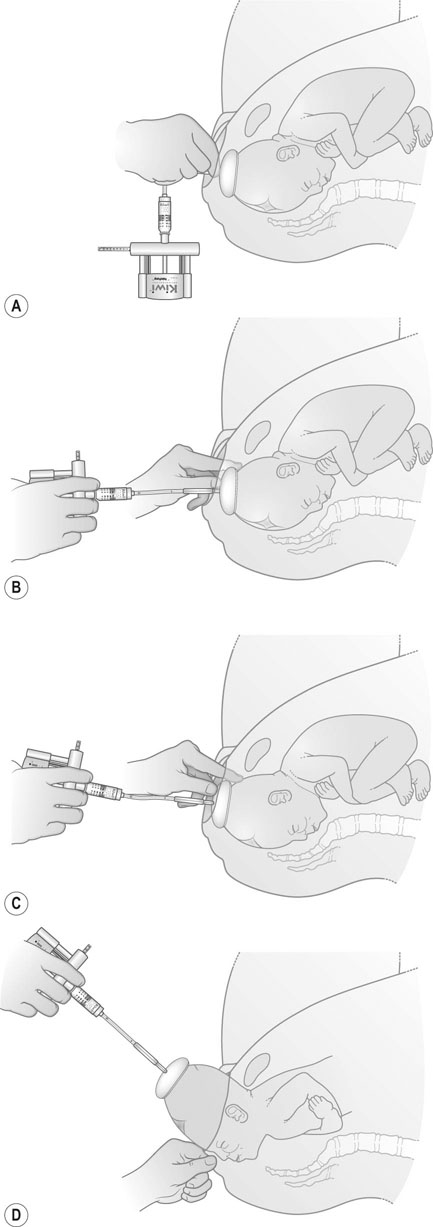

Vacuum delivery

All vacuum extractors consist of a cup that is attached to the baby’s head, a vacuum source that provides the means of attachment of the cup and a traction system or handle that allows the operator to assist the birth (Fig 12.9). As with forceps, there are two main design types of vacuum devices, the so-called ‘anterior’ cups for use in non-rotational OA extractions and the ‘posterior’ cups for use in rotational OP and OT deliveries. The cup is applied to the baby’s head at a specific point on the vertex (the flexion point) (Fig 12.11A), and traction is directed along the axis of the pelvis (Fig 12. 11B) until the head descends to the perineum (Fig 12.11C). With crowning, traction is directed upwards and the head is delivered (Fig 12.11D).

Rotational instrumental delivery

For example, Kjelland’s forceps (Fig. 12.8) has a sliding lock and minimal pelvic curve so that rotation of the fetal head with the forceps can be achieved without causing damage to the vagina by the blades. For rotational vacuum assisted delivery a ‘posterior’ cup (Fig. 12.9) will allow the operator to manoeuvre the cup towards and over the flexion point thereby facilitating auto-rotation of the head to the OA position at delivery.

Caesarean section

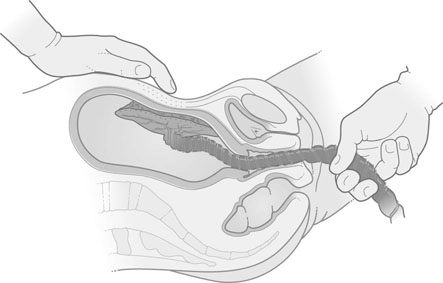

Caesarean delivery is the method by which a baby is born through an incision in the abdominal wall and uterus. There are two main types of caesarean section, namely, the more common and preferred lower uterine segment operation (Fig. 12.12) and the much less common ‘classical’ caesarean section that involves incising the upper segment of the uterus.

Indications for caesarean section

• non-reassuring fetal status (‘fetal distress’)

• abnormal progress in the first or second stages of labour (dystocia)

• intrauterine growth restriction due to poor placental function

• malpresentations: breech, transverse lie, brow

• placenta praevia and/or severe antepartum haemorrhage, e.g. abruptio placentae

• previous caesarean section, especially if more than one

• severe pre-eclampsia and other maternal medical disorders

Depending on the urgency of the clinical indication, caesarean sections have been classified into four categories based on time limits within which the operation should be performed. The most urgent, category 1 describes indications where there is immediate threat to the life of the woman or fetus; category 2 where maternal or fetal compromise is present but is not immediately life-threatening; category 3 where there is no maternal or fetal compromise but early delivery is required; and category 4 refers to elective planned caesarean section.

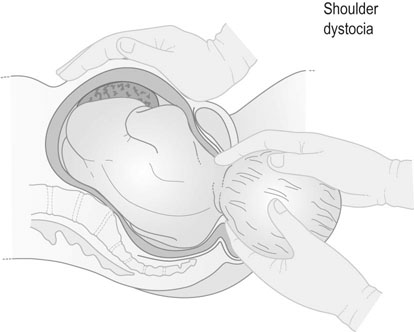

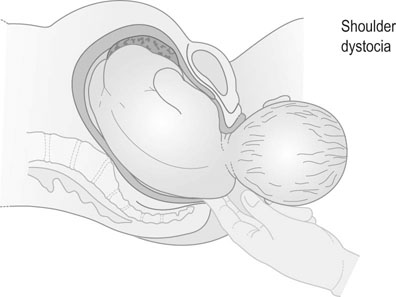

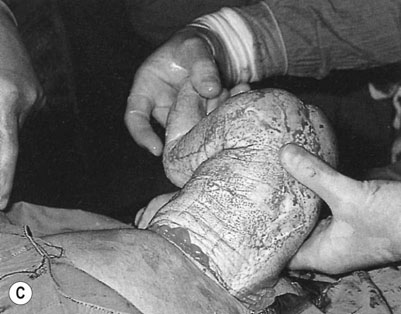

Shoulder dystocia

Normally, delivery of the anterior shoulder is achieved with gentle downward traction (Fig. 12.13) and then followed by upward traction to deliver the posterior shoulder (Fig. 12.14). If this is not successful, the recommended first line treatment for shoulder dystocia is McRobert’s manoeuvre (Box 12.2). The woman is placed in the recumbent position with the hips slightly abducted and acutely flexed with the knees bent up towards the chest. At the same time an assistant applies directed suprapubic pressure to help dislodge the anterior shoulder and for it to be in the oblique diameter of the pelvic inlet. A generous episiotomy is also performed. McRobert’s manoeuvre is successful in the majority of cases of shoulder dystocia. Other more complex manoeuvres are described such as rotation of the fetal shoulders to one or other oblique pelvic diameter, manual delivery of the posterior arm and Wood’s ‘screw’ manoeuvre.

Abnormalities of the third stage of labour

Postpartum haemorrhage

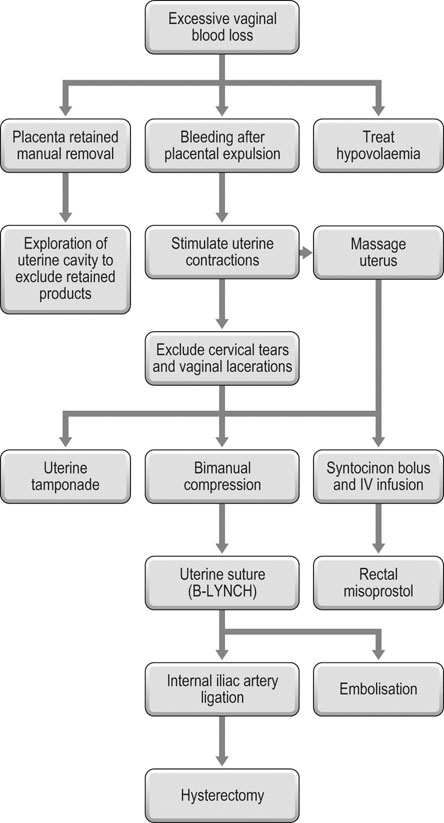

Primary postpartum haemorrhage is defined as bleeding from the genital tract in excess of 500 mL in the first 24 hours after delivery (Fig. 12.15).

Primary postpartum haemorrhage

Predisposing causes

• uterine overdistension, e.g. multiple pregnancy, polyhydramnios

• prolonged labour, instrumental delivery

• antepartum haemorrhage: placenta praevia and abruption

• multiple fibroids, uterine abnormalities

• lacerations to perineum, vagina and cervix

• uterine rupture and caesarean scar dehiscence

• haematomas of the vulva, vagina and broad ligament

• tissue: retained placenta or placental tissue

• thrombin: acquired in pregnancy, e.g. HELLP syndrome, sepsis or DIC.

Controlling the haemorrhage

• Massage the uterus to ensure it is well contracted.

• Attempt delivery of the placenta by controlled cord traction.

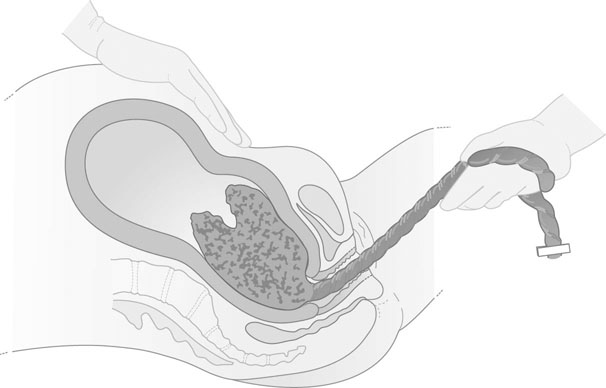

• If this fails proceed to manual removal of the placenta under spinal, epidural or general anaesthesia when the mother is adequately resuscitated.

If the placenta has been expelled:

• Massage and compress the uterus to expel any retained clots.

• Inject IV oxytocin 5 units immediately and commence an IV infusion of 40 units in 500 mL of Hartmann’s solution.

• If this fails to control the haemorrhage administer ergometrine 0.2 mg by IV injection (other than those with hypertension or cardiac disease).

• If bleeding continues administer misoprostol 1000 µg rectally (note this will take 20–25 minutes to work).

• Intramuscular or intramyometrial injection of 15-methyl prostaglandin F2α 0.25 mg can be given and repeated every 15 minutes for up to a maximum of eight doses.

• Collect blood sample to check for Hb %, coagulation disorders and for cross matching.

• Check that the placenta and membranes are complete. If they are not, manual exploration and evacuation of the uterus is indicated.

• At the same time the vagina and cervix should be examined with a speculum under good illumination and any laceration should be sutured.

• Replacement of blood loss and resuscitation: it is essential to replace blood loss throughout attempts to control uterine bleeding. Hypovolaemia should be actively treated with intravenous crystalloid, colloid, blood and blood products.

If the above measures fail, there are a number of surgical techniques that can be implemented including:

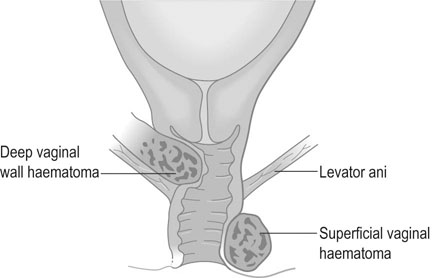

Vaginal wall haematomas

Profuse haemorrhage may sometimes occur from vaginal and perineal lacerations and bleeding from these sites should be controlled as soon as possible. Venous bleeding may be controlled by compression alone but arterial bleeding will require vessel ligation. Vaginal wall haematomas may occur in one of two sites (Fig. 12.17):

• Superficial: The bleeding occurs below the insertion of the levator ani and the haematoma will be seen to distend the perineum, causing the mother considerable pain. The haematoma must be drained and any visible bleeding vessels ligated although they are rarely identified. For this reason a drain should be inserted before the wound is re-sutured.

• Deep: The bleeding occurs deep to the insertion of the levator ani muscle and is not visible externally. It is more common after instrumental delivery than after spontaneous birth and presents with symptoms of continuous pelvic pain, retention of urine and unexplained anaemia. It can usually be diagnosed by vaginal examination as a bulge into the upper part of the vaginal wall. Alternatively, ultrasound examination will confirm the diagnosis. The haematoma is evacuated by incision and a large drain is inserted into the cavity. The vagina should be firmly packed and an in-dwelling catheter inserted into the bladder. Antibiotic therapy should be administered and, if necessary, a blood transfusion is instituted.