Management of Chronic Pain

DEFINITIONS OF PAIN AND RELATED TERMS

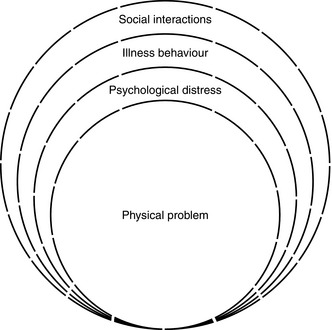

Pain: ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage’ (The International Association for the Study of Pain, http://www.iasp-pain.org/AM/Template.cfm?Section=Pain_Definitions). This definition emphasizes that pain is not only a physical sensation but also a subjective psychological event. It accepts that pain may occur in spite of negative physical findings and investigations. Pain has sensory, cognitive and motivational-affective dimensions and has been described as a biopsychosocial experience, as illustrated in Figure 46.1. This must be taken into account when assessing and planning a treatment strategy for the patient with pain.

Acute pain: pain associated with acute injury (including surgery) or disease.

Pain medicine: the diagnostic and therapeutic activities of medical practitioners.

CLASSIFICATION OF PAIN

Pain may be classified according to its aetiology.

Nociceptive Pain

Visceral Pain

Visceral hyperalgesia: increased sensitivity in the painful organ. Pain threshold is lowered in some patients with functional gastrointestinal disease and patients complain of abdominal pain in response to normally innocuous stimuli of the gut.

Visceral hyperalgesia: increased sensitivity in the painful organ. Pain threshold is lowered in some patients with functional gastrointestinal disease and patients complain of abdominal pain in response to normally innocuous stimuli of the gut.

Referred hyperalgesia from viscera, in which hypersensitivity is localized in the muscles and often associated with a state of sustained contraction. For example, patients with urinary colic typically display hypersensitivity in the muscles of the lumbar region.

Referred hyperalgesia from viscera, in which hypersensitivity is localized in the muscles and often associated with a state of sustained contraction. For example, patients with urinary colic typically display hypersensitivity in the muscles of the lumbar region.

Viscero-visceral hyperalgesia: pain in one visceral organ can be enhanced by pain in another visceral organ. Women with repeated urinary stones who were also dysmenorrhoeic manifested a higher number of colics than non-dysmenorrhoeic women.

Viscero-visceral hyperalgesia: pain in one visceral organ can be enhanced by pain in another visceral organ. Women with repeated urinary stones who were also dysmenorrhoeic manifested a higher number of colics than non-dysmenorrhoeic women.

Neuropathic Pain

Sympathetically Maintained Pain

In complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) type 1, minor injuries, including mild soft tissue trauma or a fracture, precede the onset of symptoms without any overt nerve lesion (Fig. 46.2). CRPS type II develops after injury to a peripheral nerve. Pain is the prominent feature and is characteristically spontaneous and burning in nature and associated with allodynia (abnormal sensitivity of the skin) and hyperalgesia. Autonomic changes may lead to swelling, abnormal sweating and changes in skin blood flow. Atrophy of the skin, nails and muscles can occur and localized osteoporosis may be demonstrated on X-ray or bone scan. Movement of the limb is usually restricted as a result of the pain, and contractures may result. Treatment is directed at providing adequate analgesia to encourage active physiotherapy and improvement of function. In cases with sympathetically maintained pain, sympathetic nerve block may be part of this treatment strategy.

MANAGEMENT OF CHRONIC PAIN

Patients present with pain as a result of many different pathological processes. Some examples of common painful conditions are listed in Table 46.1.

TABLE 46.1

Some Common Painful Conditions

Malignant Aetiology

Primary tumours

Metastases

Nonmalignant Aetiology

Musculoskeletal

Back pain

Osteoarthritis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Osteoporotic fracture

Neuropathic

Trigeminal neuralgia

Postherpetic neuralgia

Brachial plexus avulsion

Radicular pain of spinal origin

Peripheral neuropathy

Chronic regional pain syndrome (CRPS)

Visceral

Urogenital pain

Pancreatitis

Post-surgery

Phantom pain

Stump pain

Scar pain

Post-laminectomy

Ischaemic

Peripheral vascular disease

Raynaud’s phenomenon/disease

Intractable angina

Headaches

Cancer treatment-related: e.g. post-surgery, post-chemotherapy, post-radiotherapy pain

Assessment

Pain History

Key elements in a pain history include:

location and radiation, either verbally or graphically using a pain diagram

location and radiation, either verbally or graphically using a pain diagram

intensity, e.g. verbal rating scale, visual analogue scale, faces pain scale (children)

intensity, e.g. verbal rating scale, visual analogue scale, faces pain scale (children)

quality, to determine possible somatic or neuropathic aetiology, e.g. burning, shooting; validated screening tools such as The Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS) pain scale can be used

quality, to determine possible somatic or neuropathic aetiology, e.g. burning, shooting; validated screening tools such as The Leeds Assessment of Neuropathic Symptoms and Signs (LANSS) pain scale can be used

current medication (analgesics and others)

current medication (analgesics and others)

basic psychological assessment to include mood, coping skills, pain beliefs and self-reported disabilities; a Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale can assist as a screening tool but if full psychological evaluation is indicated, it should be performed either by a psychiatrist or by a clinical psychologist, preferably one who is an integral member of the pain management team

basic psychological assessment to include mood, coping skills, pain beliefs and self-reported disabilities; a Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale can assist as a screening tool but if full psychological evaluation is indicated, it should be performed either by a psychiatrist or by a clinical psychologist, preferably one who is an integral member of the pain management team

patient’s own ideas as to causation

patient’s own ideas as to causation

impairment and functionality (Brief Pain Inventory)

impairment and functionality (Brief Pain Inventory)

Quality of Life, e.g. EQ-5D as a standardized instrument for use as a measure of health outcome

Quality of Life, e.g. EQ-5D as a standardized instrument for use as a measure of health outcome

Medication

Many patients in pain are prescribed analgesic drugs. The pharmacology of these agents is discussed fully elsewhere (see Ch 5) and only aspects of particular relevance to their use in chronic pain are mentioned below.

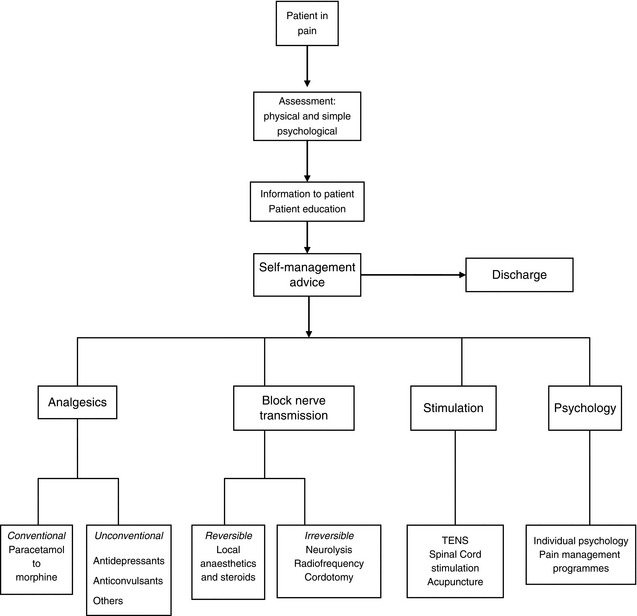

Cancer Pain

Approximately 75% of patients with advanced cancer develop significant pain before death. Most cancer pain responds to pharmacological measures, and successful treatment is based on simple principles that have been promoted by the World Health Organization and are extensively validated. Analgesic drugs should be taken ‘by mouth’, ‘by the clock’ (i.e. regularly) and ‘by the analgesic ladder’ (Fig. 46.4). Cancer pain is continuous and medication must be taken regularly. It is given orally unless intractable nausea and vomiting occur or there is a physical impediment to swallowing. The first step on the ‘analgesic ladder’ is a non-opioid, such as paracetamol, aspirin or a non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID). If this is inadequate, a weak opioid such as codeine is added. The third step is substitution of the weak opioid by a strong opioid. Inadequate pain control at one level requires progression to a drug on the next level, rather than to an alternative of similar efficacy. Adjuvant analgesics, such as tricyclic or SNRI antidepressants, NSAIDs or anticonvulsants, may be used at any stage.

Opioid Analgesics

Non-Cancer Pain: Weak opioid drugs, e.g. dihydrocodeine, are useful for moderate pain. However, they may be taken in excess, and often with only little benefit, by the patient with chronic non-malignant pain. Treatment in the pain management clinic may involve weaning the patient off such medication.

Opioid Drugs

Alternative Opioids and Alternative Routes of Administration: Oxycodone hydrochloride is a semisynthetic congener of morphine. It is available as an immediate-release and a sustained-release preparation. It is approximately twice as potent as morphine (i.e. 5 mg of oxycodone is equivalent to 10 mg of oral morphine). Its advantage in renal failure is the lack of detectable clinically relevant active metabolites, therefore avoiding accumulation. Prolonged release oxycodone is available in combination with prolonged release naloxone to counteract constipation.

Transdermal Drug Delivery: If a patient is unable to take medication by mouth, there are various alternative routes for opioid administration. A transdermal drug delivery system has been developed for fentanyl and buprenorphine. Fentanyl patches are applied to the skin and drug from the reservoir diffuses through the rate-controlling membrane and forms a subcutaneous depot from which the drug is taken up into the circulation. There is wide variation in absorption rates and time to steady-state serum concentrations of fentanyl. After removal of the patch, the terminal half-life has been shown to be 17 ± 2.3 h, indicative of the time taken for the drug to clear from the subcutaneous depot. Transdermal fentanyl is available in patches which deliver 12.5, 25, 50, 75 or 100 μg h–1 of fentanyl. They should be placed on unbroken skin, usually on the upper body, and need to be changed every 72 h. An appropriate dose of immediate-release morphine or a buccal or transnasal fentanyl preparation should be prescribed for breakthrough pain.

Subcutaneous Administration: Continuous subcutaneous administration is another alternative method of administration if oral medication cannot be taken. A small, portable battery-operated syringe driver fitted with a 20 mL syringe containing the total daily opioid dose is usually used. Because of its greater solubility, diamorphine is the drug of choice in the UK for this route of administration. A conversion ratio of 3 mg oral morphine to 1 mg subcutaneous diamorphine is used.

Spinal Administration: Opioids may be administered spinally, either epidurally or intrathecally, for:

Co-Analgesics

Anticonvulsants: Anticonvulsants are used in the treatment of neuropathic pain. The precise mechanism of action varies among different anticonvulsants. For example, it is thought that carbamazepine blocks sodium channels and that gabapentin and pregabalin act on the α2δ subunit of the calcium channel. Therefore, if one anticonvulsant at maximum dosage is ineffective, then it is worthwhile trying another. Gabapentin, pregabalin, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine and phenytoin are used in neuropathic pain and trigeminal neuralgia.

Tricyclic and SNRI Antidepressants: Tricyclic and SNRI antidepressants have a role in the management of pain, independent of their effect on mood. Tricyclic drugs and SNRIs are postulated to act as analgesics by reducing the reuptake of the amine neurotransmitters noradrenaline and serotonin into the presynaptic terminal, increasing the concentration and duration of action of these substances at the synapse and thereby enhancing activity in the descending inhibitory pain pathway. Tricyclics also block sodium channels and suppress ectopic neuroma discharge.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, such as fluoxetine, appear to be less effective analgesics.

Antiarrhythmic Drugs

Ketamine: Ketamine is an NMDA receptor antagonist which has been used successfully as an analgesic via intravenous, subcutaneous and oral routes. Psychometric side-effects may be a problem.

Capsaicin: Capsaicin is an alkaloid derived from chillies. It depletes substance P in local sensory nerve terminals. Local application may alleviate pain in painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy, osteoarthritis, postherpetic neuralgia, intercostobrachial neuralgia and psoriasis.

Cannabinoids: Animal studies suggest that cannabinoids reduce hyperalgesia and allodynia in neuropathic, inflammatory and cancer pain. Human trials have also reported modest benefit in neuropathic pain. Cannabinoids act on CB1 receptors, which are located in the brain, and their CB2 counterparts found peripherally. Further research is needed to identify which cannabinoids may produce analgesia without psychotropic side-effects.

Oral Corticosteroids: The mechanism by which corticosteroids produce analgesia is unknown. They reduce inflammatory mediators, specifically prostaglandins. They reduce peritumour oedema, thus relieving pain by reducing pressure on adjacent pain-sensitive structures. They are administered for cerebral metastases, spinal cord compression, superior vena caval compression and neural infiltration or compression. In cancer patients, they are also prescribed for their euphoric effect and to stimulate appetite.

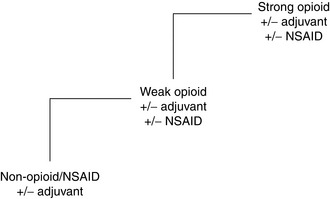

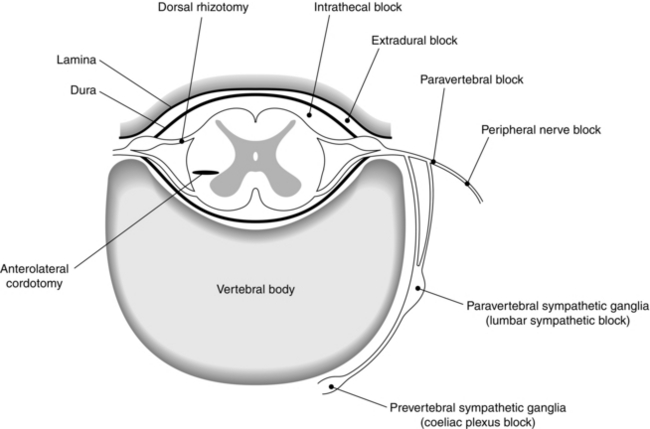

Interventional Pain Therapies

Potential sites for neural blockade are shown in Figure 46.5, and indications for neural blockade are listed in Table 46.2. Some comments about commonly performed nerve blocks are made in the section below. For a full description of the techniques of neural blockade, the reader should consult suggested texts in the further reading section.

TABLE 46.2

Indications for Neural Blockade

| Nerve Block | Indications |

| Trigger point injections | Myofascial pain, scar pain |

| Somatic nerve block | Nerve root pain, scar pain |

| Trigeminal nerve block and branches | Trigeminal neuralgia |

| Stellate ganglion block | SMP, CRPS |

| Coeliac plexus block | Intra-abdominal malignancy, especially pancreas |

| Superior hypogastric plexus block | Malignant pelvic pain |

| Lumbar sympathetic block | Ischaemic rest pain SMP, CRPS Phantom and stump pain |

| Epidural steroids/root canal injections | Nerve root pain, benign or malignant |

| Lumbar and cervical medial branch blocks | Back pain Whiplash cervical pain |

| Intrathecal neurolytics | Malignant pain |

| Percutaneous cervical cordotomy | Unilateral somatic malignant pain, short life expectancy |

SMP, sympathetically maintained pain; CRPS, complex regional pain syndrome.

Agents

Local Anaesthetics: Local anaesthetics block sodium channels and may be used for both diagnostic and therapeutic injections. They have been injected into muscle trigger points for the relief of myofascial pain and it has been shown that prolonged relief of pain may result sometimes from local anaesthetic blocks to peripheral nerves.

Neurolytic Techniques

Chemical Neurolysis: The commonest neurolytic agents used are phenol and ethyl alcohol. Phenol acts by coagulating proteins and destroys all types of nerves, both motor and sensory. It is available in water or in glycerol. Its most frequent indication is for lumbar sympathetic block for peripheral vascular disease. Large systemic doses cause convulsions followed by central nervous system depression and cardiovascular collapse. Alcohol is the neurolytic agent of choice for coeliac plexus block in patients with intractable abdominal pain due to pancreatic cancer, when the large volume required prohibits the use of phenol. It produces a higher incidence of neuritis than phenol and is not used for other blocks.

Radiofrequency Lesions: Radiofrequency lesioning is indicated for patients in whom non-invasive treatments have failed. A destructive heat lesion is produced by a radiofrequency current generated by a lesion generator. The radiofrequency electrode comprises an insulated needle with a small exposed tip. A high frequency alternating current flows from the electrode tip to the tissues, producing ionic agitation and a heating effect in tissue adjacent to the tip of the probe. The magnitude of this heating effect is monitored by a thermistor in the electrode tip. Damage to nerve fibres sufficient to block conduction occurs at temperatures above 45°C, although in practice most lesions are made with a probe tip temperature of 60–80°C. An integral nerve stimulator is used to ensure accurate positioning of the probe. Whereas the spread of neurolytic solutions is unpredictable, radiofrequency lesions are more precise. The size of the lesion depends on the tip temperature, the duration of the current and the length of the exposed needle tip. Lower-temperature lesions are now being used in an attempt to produce analgesia without nerve destruction in pulsed radiofrequency lesioning.

Stimulation-Induced Analgesia

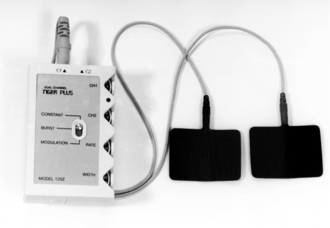

Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation

A small battery-powered unit is used to apply the electrical stimulus to the skin via electrodes (Fig. 46.6). These are placed over the painful area, on either side of it or over nerves supplying the region, and stimulation is applied at an intensity which the patient finds comfortable. Adverse effects are minimal, with allergy to the electrodes being the commonest problem encountered. TENS is used for a variety of musculoskeletal pains and has been advocated recently for refractory angina. Tolerance to TENS does occur sometimes. It may be possible to overcome this by changing stimulation variables.

British Pain Society, Opioids for persistent pain. http://www.britishpainsociety.org/book_opioid_main.pdf

British Pain Society, Cancer pain management. http://www.britishpainsociety.org/book_cancer_pain.pdf

Cousins M.J., Carr D.B., Horlocker T.T., Bridenbaugh P.O., eds. Neural blockade in clinical anesthesia and pain medicine, fourth ed., Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer, Lippincott, Williams and Wilkins, 2008.

McMahon S., Koltzenburg M., eds. Wall and Melzack’s textbook of pain, fifth ed., London: Elsevier, 2005.

Moore, A., Edwards, J., Barden, J., McQuay, H. Bandolier’s little book of pain. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003.

Singh, M.K., Patel, J., Chronic pain syndrome. http://emedicine. medscape.com/article/310834-overview.

Stannard C.F., Kalso E., Ballantyne J., eds. Evidence-based chronic pain management. John Wiley & Sons Ltd, Chichester, 2010.

Twycross, R., Wilcock, A. Symptom management in advanced cancer. Oxon: Radcliffe Medical Press; 2001.

Waldman, S.D., Winnie, A.P. Interventional pain management. Philadelphia: W B Saunders; 1996.