Management of chronic impairments in individuals with nervous system conditions

MYLA U. QUIBEN, PT, PhD, DPT, GCS, NCS, CEEAA

After reading this chapter the student or therapist will be able to:

1. Analyze how the aging process may affect people with lifelong functional limitations and challenges in life participation.

2. Analyze the unique challenges faced by people with chronic motor impairments such as those associated with cerebral palsy, genetic malformations, developmental disabilities, postpolio syndrome, spinal cord injury, and traumatic or acquired head injury during the aging process.

3. Evaluate this population of patients/clients with sensitivity and skill, incorporating precautions and effectiveness of interventions.

4. Provide a framework for the examination process for individuals with chronic conditions.

5. Present holistic intervention considerations for individuals with chronic motor impairments.

6. Identify gaps in knowledge and research in the management of aging individuals with chronic neuromuscular conditions.

7. Appreciate the complexity of examination, evaluation, and management of the aging patient with chronic motor impairments.

The aging process typically leads to gradual physiological changes in muscle strength, flexibility, and joint mobility and changes in balance and endurance. Physical activity and a healthy lifestyle have been shown to address age-related changes by delaying the decline and deterioration; however, age-related changes such as osteoarthritis and vascular changes are still likely to occur to varying degrees despite a healthy lifestyle. Healthy but sedentary older individuals report more problems in activities of daily living (ADLs) than do those who continue to be physically active and who previously had an active lifestyle.1–3

In the realm of chronic problems in life participation, individuals who experienced the effects of polio in their younger years give clinicians an enlightening example of the chronic interaction among neurological and functional impairments, recovery, effects of aging, and health care. As a chronic condition, individuals who dealt with polio can teach therapists to reconsider and reevaluate their approach to individuals who are now experiencing activity limitations, impairments, and ineffective postures and movement. The challenges of aging with chronic body system problems or impairments are encountered by individuals who have postpolio syndrome (PPS); those who acquired CNS insult at birth (developmental disabilities including cerebral palsy [CP; see Chapter 12] and Down syndrome [see Chapter 13]); and those who acquired injury through disease or trauma sometime in the life span development process (traumatic brain injury [TBI; see Chapter 24], multiple sclerosis [MS; see Chapter 19], and spinal cord injury [SCI; see Chapter 16]).

The discussion of chronic impairments brings several questions to the forefront:

What is the course of age-related medical conditions common in individuals with chronic impairments?

What is the course of age-related medical conditions common in individuals with chronic impairments?

Do age-related conditions vary among the developmental or genetic diseases or among conditions occurring at one point during the life span?

Do age-related conditions vary among the developmental or genetic diseases or among conditions occurring at one point during the life span?

What are the prevalence and/or incidence of secondary conditions in individuals with chronic impairments?

What are the prevalence and/or incidence of secondary conditions in individuals with chronic impairments?

Have specific treatment protocols for health provision for this population been identified?

Have specific treatment protocols for health provision for this population been identified?

What is the state of dissemination of information related to aging and health to people affected by these conditions?

What is the state of dissemination of information related to aging and health to people affected by these conditions?

How has the effect of aging with chronic body system problems changed the ability of these individuals to participate in life as well as their perceived quality of life?

How has the effect of aging with chronic body system problems changed the ability of these individuals to participate in life as well as their perceived quality of life?

This chapter aims to provide a holistic view of the management of the chronic problems of individuals with nervous system impairments, with consideration given to the effects of aging and compensation over time. Movement emerges from the interaction among the individual, task, and environment,4 with several variables and degrees of freedom. Therefore physical therapists (PTs) and occupational therapists (OTs) need to examine and address multisystem impairments and contributions to movement while appreciating the changing dynamics of a highly complex movement system.

Diagnoses with underlying chronic consequences

Developmental conditions

With increasing life expectancy, mainly as a result of innovations in health care, a unique group of individuals with chronic conditions are subject to age-related changes. Individuals with developmental disabilities constitute a growing segment of the aging society. This is a broad topic, in part because of the many conditions that are categorized as developmental disability. According to the Administration on Developmental Disabilities and the Administration for Children and Families,5 developmental disabilities are severe, chronic functional limitations attributable to mental or physical impairments or a combination of both, that manifest before age 22 years and that are likely to continue indefinitely. These result in substantial limitations in three or more of the following areas: self-care, receptive and expressive language, learning, mobility, self-direction, capacity for independent living, and economic self-sufficiency. These individuals also have a continuous need for individually planned and coordinated services.6 The definition envelops a wide range of conditions leading to significant and lifelong disabilities. This group includes those with genetic and neurological conditions, two of the more common of which are CP (see Chapter 12) and Down syndrome (DS; see Chapter 13).

The question of whether unexpected changes among people with neurodevelopmental disabilities occur as they age and how these changes compromise functioning with progressive aging is of massive importance with the emergence of a population of individuals with developmental disabilities with increased life expectancy and concurrent increase in older-age–related diseases. According to Heller7 the number of adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities aged 60 years and older is projected to nearly double from 641,860 in 2000 to 1.2 million by 2030 owing to increasing life expectancy and the aging of the Baby Boomer generation. With the aging of adults with developmental and genetic disorders a new societal issue looms, as individuals with developmental disabilities have a lifelong need for external support. Much is unknown about the long-term effects of aging and maturation in adults with these conditions.

Adults with several types of developmental disabilities have life expectancies similar to those of the general population, excluding adults with particular neurological conditions and with more severe cognitive deficits. Recent studies show the mean age at death ranges from the mid-50s for adults with severe disabilities or DS, to the early 70s for those with mild to moderate intellectual disabilities.8–10

Concurrent with an increased life span, some evidence exists that certain individuals with developmental disabilities have experienced an increase in age-related diseases. Of the limited information available, research has shown that aging affects certain genetic and neurologically based intellectual and developmental disabilities that may increase the risk of age-related pathologies and lead to an increased occurrence of coincident conditions.11 Of several developmental conditions, DS has been the subject of a substantial body of research. DS is known for resulting in advanced aging that includes a higher risk for Alzheimer disease and select organ dysfunctions.11–13

Evidence exists that adults with CP, considered a life span disability, lose functional abilities earlier than individuals who are able-bodied.14 For CP, evidence is also increasingly pointing to specific age-related outcomes such as the effects of deconditioning, limitations with performance reserve, and possibly a shorter life span.11 In adults with CP, secondary conditions commonly described in research primarily are related to the long-term effects on the musculoskeletal system, such as pain, degenerative joint disease, and osteoporosis.11,15,16 Secondary impairments in CP can progress subtly and may not appear until late adolescence or adulthood.15 Age-related health conditions are also seen in other genetic and neurological disorders as the affected individuals age. However, the nature of these risks lacks extensive substantiation in the literature.

Overall, knowledge of adult health issues for older people with developmental disabilities is limited.7 Several reasons contribute to the lack of knowledge. Limited health care programs exist for this population, likely because this is an emerging population. Most of the existing literature is in the pediatric domain rather than dealing with age-related issues. Although these individuals were likely seen by therapists for various functional limitations throughout their lives, the professional training that health care providers have received regarding the care of these individuals has focused on early childhood and school-aged children. As a result, many adolescents and adults with developmental disabilities have difficulty accessing appropriate health care information regarding secondary conditions resulting from their specific disabilities. Moreover, in general, older individuals with developmental disabilities have more difficulty in finding, accessing, and paying for high-quality health care.7 Communication difficulties also limit the understanding of the experiences of aging adults with developmental disabilities. Evidence exists, however, showing that obesity and inactivity are more common in individuals with developmental disabilities than in the general population.17 Bazzano and colleagues17 identified several reasons for this health discrepancy, including individual and community factors, physical challenges, segregation from the community, lack of accessible fitness facilities and developmentally appropriate community programs, and cognitive deficits.

Given trends of increasing survival and longevity observed among individuals with developmental disabilities, it is sensible to consider a more in-depth look at the aging process among a variety of neurodevelopmental conditions and the need for a holistic approach. Although some literature exists regarding life span changes with these disorders, particularly DS and CP, there is lack of confirming evidence for most of these conditions. Horsman and colleagues14 advocate for research on the expectations regarding aging for adults with CP, including preventive measures to lessen the effects of secondary impairments. This recommendation applies to developmental life span conditions and other chronic conditions that are subject to age-related changes that may be magnified or made worse by existing impairments and limitations. Evidence-based research is necessary to better understand the long-term effects of aging on adults with developmental and chronic conditions. The challenge then is to provide a holistic examination that involves a multisystem approach and to provide appropriate referrals as necessary to address the multiple needs of individuals with developmental disabilities.

Neurological conditions acquired in the life span: spinal cord injury, traumatic brain injury, postpolio syndrome

In the realm of management of chronic movement dysfunction, PPS—the late effects of polio—becomes a model case for other chronic neuromuscular conditions. There is much to learn from the complex nature of the late effects of polio and the effects of aging on an already stressed system. The cause must be briefly discussed to further understand the possible effects of aging. PPS can affect polio survivors years after recovery from the initial polio infection and is characterized by multifaceted symptoms that lead to decline in physical functioning.18 PPS manifests with progressive or new muscle weakness or decreased muscle endurance in muscles that were initially affected by the polio infection and in muscles that were seemingly unaffected; generalized fatigue; and pain.18 The exact cause of PPS remains unknown on the basis of review of the literature. Although it is not clear what exactly causes the new symptoms, there appears to be a consensus that insufficient evidence implicates the reactivation of the previous poliovirus.19 Underlying causes have been proposed in a variety of hypotheses from several authors, with aging playing a key role.20–24

The suggestion that aging contributes to PPS is supported in the literature.21,25,26 By the fifth decade of life, loss of anterior horn cells begins, and by age 60 years the loss of neurons may be as high as 50%.27 Age-related changes superimposed on the already limited motor neuron pool after polio appear to be important factors in the development of PPS. With the effects of the normal aging process, the remaining anterior horn cells are further reduced to a point at which the deficits caused by the initial insult cannot be overcome. The loss of even a few neurons from a greatly exhausted neuronal pool potentially results in a disproportionate loss of muscle function.20,28 The loss of motor neurons from aging alone may not be a considerable factor in PPS because studies20 have failed to link chronological age and the onset of new symptoms. Rather, it is the length of the interval between the onset of polio and the appearance of new symptoms that seems to be more critical.

Another plausible hypothesis alludes to overuse and fatigue of the already weakened muscles as a factor in the development of new muscle weakness.19,29,30 A study by Trojan and colleagues30 provides support to this hypothesis. Their results suggest that length of time since acute polio, joint and muscle pain, physical activity, and weight gain are factors associated with PPS. Years of overuse after recovery from polio causes a metabolic failure leading to an inability to regenerate new axon sprouts. The exact cause of degeneration of axon sprouts is not known. Evidence to support this hypothesis can be inferred from muscle biopsies, electrodiagnostic tests, and clinical response to exercise.20 McComas and colleagues31 suggested that neurons that demonstrated histological recovery from the initial virus were possibly not physiologically normal and were potentially vulnerable to premature aging and failure.

Other proposed hypotheses include persistence of dormant poliovirus that was reactivated by unknown mechanisms, an immune-mediated response, hormone deficiencies, and environmental contaminants.20 Another hypothesis points to the loss of anterior horn cells during the initial polio as a factor.19,21 Findings from Trojan and colleagues30 support the hypothesis that the severity of the initial motor unit involvement, seen as weakness in acute polio, is critical in predicting PPS. Individuals at greatest risk for PPS had severe attacks of paralytic polio, although individuals with milder cases also had symptoms.20 These hypotheses have not been completely examined, and currently the evidence is not strong enough to support any one possible cause. Clinically it is difficult to assume that only one factor causes symptoms. The chronicity of the disease lends weight to the possibility that more than one factor contributes to the individual’s symptoms.

McNaughton and McPherson32 state that the simple descriptive labels “late problems after polio” and “of late deterioration after polio” are less limiting and do not imply a direct link with the previous polio diagnosis. Post-Polio Health International33 uses the terminology “late effects of polio and polio sequelae” as the most inclusive category. Late effects of polio and polio sequelae pertain to health problems that are a result of chronic impairments from polio and may include degenerative arthritis from overuse, bursitis, or tendinitis. A subcategory under this heading is PPS leading to decreased endurance and decreased function.

Currently no definitive test exists in the literature to diagnose the late effects of polio or PPS. It remains a diagnosis of exclusion, and as such the diagnostic process for PPS is challenging and may be long. Halstead and Gawne34 identified cardinal symptoms of PPS as new or increased muscle weakness, fatigue, and muscle and joint pain with neuropathic electromyographic changes in an individual with a definite diagnosis of polio. Diagnostic electromyography (EMG) may be required or used when the muscle pattern or history is atypical.

The criteria most commonly used for establishing a medical diagnosis of PPS were developed by Halstead35 and are as follows:

1. A confirmed history of paralytic polio in childhood or adolescence

2. Partial to complete muscle strength and functional recovery

3. A period of at least 15 years of neurological and functional stability

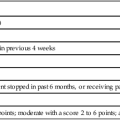

4. Onset of two or more new health problems listed in Table 35-1

TABLE 35-1

| NO. | % | |

| HEALTH PROBLEMS | ||

| Fatigue | 117 | 89 |

| Muscle pain | 93 | 71 |

| Joint pain | 93 | 71 |

| Weakness | ||

| Previously affected muscles | 91 | 69 |

| Previously unaffected muscles | 66 | 50 |

| Cold intolerance | 38 | 29 |

| Atrophy | 37 | 28 |

| ADL PROBLEMS | ||

| Walking | 84 | 64 |

| Climbing stairs | 80 | 61 |

| Dressing | 23 | 17 |

ADL, Activity of daily living.

Modified from Halstead L, Wiechers D, editors: Research and clinical aspects of the late effects of poliomyelitis, White Plains, NY, 1987, March of Dimes, p 17.

5. No other medical conditions to explain these new health problems

Dalakas36 identified additional inclusion criteria in the diagnosis: residual asymmetrical muscle atrophy, with weakness, areflexia, and normal sensation in at least one limb and normal sphincteric function and deterioration of function after a period of functional stability unexplained by primary or secondary condition.

Several individuals who recovered from polio during the early epidemics were encouraged to exercise for years and to use heroic compensatory methods for function. An exhaustive regimen of daily stretching and strengthening, demanding compliance from individuals and their support systems, was strongly encouraged. Orthotics and assistive devices were promoted as a means toward independent mobility. The outcomes of rigorous training were individuals who adapted and compensated with their remaining capabilities. Compensations include use of muscles at high levels of their capacity, substitution of stronger muscles with increased energy expenditure for the task, use of ligaments for stability with resulting hypermobility, and malalignment of the trunk and limbs. With the late effects of polio or a diagnosis of PPS, many of these individuals may have extreme difficulty dealing with these new problems because of the attitude of “working hard” to reeducate weakened muscles and compensate for loss of function after the initial diagnosis.37–40 The new symptoms of PPS, which limits their motor function and likely impairs established personal and societal roles, require that they not work hard or overexert themselves. These two approaches are contradictory and can leave an individual frustrated and confused over therapeutic recommendations.

Spinal cord injury and traumatic brain injury

For persons with SCI and TBI, a trend is seen toward increasing awareness on the effects of aging on the functional status of this group. Owing to medical advances, patients are now living 20 to 50 years past their time of injury. Numerous studies have been done describing quality-of-life issues for people with TBI; however, those studies seldom look specifically at changes in functional levels or what can be done to ameliorate the declines.41–43

McColl and colleagues,44 studying the impact of aging on people after SCI, have identified major categories of problems related to aging, such as musculoskeletal problems and joint, sensory, and connective tissue changes; chronic urinary tract infections; heart, respiratory, and other chronic diseases; secondary complications of the initial lesions, such as syringomyelia; and problems related to social and cultural acceptance and access or barriers. Evidence on specific age-related changes is presented in the section on examination.

Decreases in perceived health status and in functional abilities with increases in additional assistance for ADLs have been documented for aging individuals with SCI.45–49 In a study of 150 people aging with an SCI, nearly 25% reported decreases in the ability to perform functional activities that they had been able to handle after the acute rehabilitation phase. The subjects who reported decreases in functional ability were generally older (45 years compared with 36 years) and had longer postinjury periods (18 versus 11 years). The most common symptoms reported by the individuals with decreases in functional status were related to fatigue, pain, and muscle weakness. The ADLs reported to be more difficult were transfers, bathing, and dressing. To maintain their functional levels, those with declines in functional ability reported needing additional equipment.45

The need for further assistance with ADLs was echoed in a study by Gerhart and colleagues of individuals with SCI 20 years after the initial injury.46 The study showed that 22% of the subjects reported an increased need for support with ADLs. Compared with a general group of nondisabled men and women aged 75 to 84 years in which 78% of the men and 64% of women did not need help with ADLs, the population of persons with SCI needed increasing support to remain independent, and the need for help occurred at a younger age. On average, those with quadriplegia required more help with ADLs around the age of 49 years, whereas those with paraplegia were able to maintain their functional level until age 54 years. The groups showing functional decreases reported greater fatigue, increased muscle weakness, pain, stiffness, and weight gain.46 Other studies support the findings that 5, 10, and 15 years after the initial SCI, an association with the need for additional help with increasing age existed.47

Liem and colleagues,48 referencing an international data set of people with SCI, investigated a subset of 352 people at least 20 years after their injury. Thirty-two percent of the subjects reported needing increased help with transfers and housework compared with their functional abilities at acute hospital discharge. With increasing age, women had a higher incidence of reported musculoskeletal impairments, which may have been related to biomechanical differences between men and women (e.g., 40% lower upper body strength).

In addition to the need for ADL support, neurogenic bowel and bladder symptoms also worsen with age in some people with SCIs. With changes in general health status, polypharmacy, decreased activity, and poor nutritional patterns, bowel problems (particularly constipation) become more of an issue. Although constipation seems like a minor issue relative to paralysis, those with SCIs report significant abdominal distention and pain, an increased incidence of perineal and sacral skin breakdown, and in some cases autonomic dysreflexia. In addition to the discomfort of chronic bowel dysfunctions, the required bowel care programs may take more time, which can lead to increased psychosocial issues associated with anxiety about bowel accidents in social and work situations and may take time away from social activities for both the person with an SCI and the caregiver. For those with continuing bowel problems that interfere with life and work activities, a colostomy may be an option that increases independence from caregiver support during the bowel program.50 Another complicating factor related to bowel dysfunction is the typical treatment for pain complaints. Because the origin of pain is often illusive, the most common treatment involves oral medications rather than referrals for therapeutic interventions. Pain medications, especially opioids, increase gastrointestinal difficulties in nondisabled populations,51 and the problem for patients with SCI is compounded.

Charlifue and colleagues,52 drawing on the National Spinal Cord Injury Database of 7981 individuals with SCIs that occurred from 1973 to 1998, found a slight decrease in perceived health status the longer one lived after SCI. Evidence was also found that those injured later in life had a higher number of rehospitalizations after injury than those injured at a younger age. Despite palpable problems with the statistical issues within the sample, the study clearly indicated that the best predictor of a complication is a previous history of that complication. On the basis of their results, Charlifue and colleagues52 suggest that prevention of complications is the best approach to improve quality of health and quality of life for people aging with SCI.

Individuals with TBI are often neglected by professional health care and insurance providers after the acute rehabilitation period. According to Levin,53 before 1980, individuals with brain injuries were considered “dead on arrival.” Persons who would have died from the TBI several decades ago are now living into old age and are coping with the changes caused by the aging process superimposed on their physical limitations and cognitive problems. Of great concern is the possible relationship between a history of brain injury and increased cognitive changes along the dementia continuum.54 Cognitive decline in the nondisabled population is a problem, but the additive effect for a person with a previous TBI may seriously impair the person’s coping mechanisms when dealing with his or her own health and self-care needs.55

Extensive work has been done on rehabilitation programs and quality-of-life issues related to head injury and, to a lesser extent, cerebral vascular accidents.56 (See Chapters 23 and 24 for interventions for head injury and hemiplegia.) Unfortunately, the focus of rehabilitation after a TBI has been on the acute and rehabilitation stages of treatment and not the chronic problems that follow this group of patients into their older years. As with other chronic conditions, few patients see a therapist after they are discharged from rehabilitation unless they have new acute events such as musculoskeletal problems or a medical condition that causes a change in functional status.

Although TBI is a lifetime disability, little attention has been paid to the needs of aging persons with a TBI who may have recurring needs for physical and cognitive rehabilitation and retraining over the life span. Individuals who sustain a TBI in the older years will likely have different needs from those injured at a younger age. In a study on the effect of age on functional outcome in mild TBI, Mosenthal and colleagues57 found that those injured later in life (after age 60) had longer inpatient rehabilitation periods and lagged behind younger patients in functional status at the point of discharge; however, similar to the younger individuals who sustained a head injury, the over-60 individuals showed measurable improvement during the 6-month study period. Therefore, aggressive management of older patients with TBI is recommended, and older patients may require continuing management owing to the overlying issues of the aging process.57 This is echoed in the National Institutes of Health (NIH) consensus document on the treatment of people with TBI, which suggests that specialized interdisciplinary treatment programs need to be put in place to deal with the medical, rehabilitation, family, and social needs of people with TBIs who are over the age of 65 years. The document also concludes that access to and funding for long-term rehabilitation is necessary to meet long-term needs; however, it recognizes that changes in payment methods by private insurance and public programs may jeopardize the recommendations.58

Although the authors of the NIH document recognize the need to deal with the aging processes associated with TBI, there continues to be a lack of services and trained professionals available, especially at the community level.59 As with the SCI population, work is now being done to investigate the relationships among TBI, aging, and health. Breed and colleagues60 found that older individuals with TBI were more likely than their age-matched nondisabled peers to report metabolic, endocrine, sleep, pain, muscular, or neurological and psychiatric problems. Their findings support those of Hibbard and colleagues61 and Beetar and colleagues,62 which suggest that medical personnel need to be prepared to treat a broad range of health issues in the aging TBI population. Fewer of the studies on long-term outcomes and issues in TBI extend to the 10- and 15-year postinjury periods that have been examined for patients with SCIs. In studies 5 years after the initial TBI, improvements in physical and social functions were noted in most areas for at least the first 2 years after injury, with the exception that those with a history of alcohol or drug abuse did less well. One could assume that continued abuse of alcohol or drugs would bode ill for individuals aging with a TBI.63 In one study of 946 children and adolescents who sustained a TBI, Strauss and colleagues64 found that patients with severe and permanent mobility and feeding deficits had higher mortality rates, with a 66% chance of surviving to age 50 years. In contrast, survivors with fair or good mobility had a life expectancy only 3 years shorter than that of the general population. However, because both severely and mildly injured individuals with a TBI can live well into and beyond their 50s, the impact of aging on the physical and cognitive deficits must be dealt with assertively to prevent superimposed disability.

Examination of individuals with chronic impairments

Estimates of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services indicate that 40 to 54 million Americans have some type of chronic condition or disability.65,66 Conditions are diverse and may be related to trauma or chronic conditions such as MS.66 Trends of increasing survival and longevity are now being observed among individuals with chronic conditions as they experience aging processes. It is timely to consider how to manage individuals with chronic impairments.

Examination of individuals with chronic impairments and disabilities is challenging to say the least. Not only are the impairments and functional limitations diverse, but the combinations of these impairments and limitations are many and unique to each individual owing to societal, personal health, environmental, and psychological considerations. Moreover, the effects of aging will likely affect individuals differently depending on existing impairments, functional limitations, current health status, and each individual’s attitude toward health and maintaining their functional status and lifestyle. This entails a more thorough, methodical, multisystem examination with a meticulous health interview and wellness model (see Chapter 2).

Examination: systems model

Bottomley67 identifies essential components of a comprehensive geriatric assessment as psychosocial, functional, mental, and social health elements. These components are applicable to individuals with chronic neuromuscular impairments, who with aging are experiencing new symptoms or a magnification of preexisting impairments. Box 35-1 shows a sample examination template for this population.

Challenges of examination of individuals with chronic conditions

Assessment of individuals with chronic nervous system conditions is challenging because of the diversity of impairments, the nonspecific nature of symptoms, and the complex interaction of several factors, including the heterogeneous effects of aging. Depending on their underlying health conditions, individuals with chronic conditions may have higher risks than others of developing preventable health problems.66 In comparing nondisabled individuals with persons with disabilities, Iezzoni68 found that the latter group is much more likely to have higher obesity and overweight rates and higher rates of depression, anxiety, and stress. Twenty-seven percent of adults with major physical and sensory impairments are obese, compared with 19% of those without major impairments.68 Thirty-four percent of individuals with major difficulties in walking reported frequent depression or anxiety compared with 3% among those without disabilities.68 Information on predisposition to conditions such as these is important for the health care provider during the health interview and examination process.

The absence of specific medical diagnostic tests adds to the dilemma, as does the continuing uncertainty of the underlying cause and the lack of curative intervention. Health care professionals’ limitations in knowledge of age-related medical disorders that are common in people with these conditions, including the prevalence and incidence of medical conditions with neurodevelopment disabilities also add to the complexity. Box 35-2 provides several important pointers for examining this population of patients and clients.

The individual with chronic impairments who is currently facing an active pathology likely has adapted to his or her existing system impairments and activity limitations. Depending on their underlying health conditions, some individuals with chronic conditions may have higher risks than others of developing preventable health problems.66 Thus, from an examination viewpoint, the critical task of the health care provider is determining what new changes to the individual’s current abilities and disabilities have been brought on by the active pathology. These changes will likely affect the current functional abilities (e.g., mobility, ADLs), as will preexisting system impairments such as deficits in strength and endurance, pain, and so on. Regardless of the level of deficit, these individuals have some prior knowledge of deficits that affect function, which may help or may hinder their willingness to participate.

PTs may develop diagnostic focuses regarding functional limitations different from those of OTs. These variances depend on the functional activity limitations identified by the patient and the professional.69,70 An example of the physical therapy diagnostic process can be found in Appendix 35-A.

Health history

Therapists typically collect health history information as part of a comprehensive examination. The history information along with the symptom investigation and review of systems and physical examination will provide guidance in the differential diagnosis process (see Chapters 7 and 8) and in the choice of examination and intervention techniques.

The information from the history will be useful in determining the possible cause of current difficulties or symptoms for which the patient/client is now seeking intervention (Box 35-3). Fatigue or pain may be present from unnecessary and inefficient movement strategies or from high levels of activity. Information on the habitual sleeping, sitting, standing, and walking postures along with ineffective use of devices may alert the clinician to possible factors contributing to the patient’s current symptoms or difficulties.

Systems review

A systems approach to the examination is essential because individuals with chronic conditions have a multitude of possible impairments with superimposed age-related conditions. This situation is best illustrated when examining individuals with PPS. The patient presentation in this condition is a complex interaction of all systems along with the effects of aging, previous interventions, and environmental, psychosocial, and medical aspects of care. The initial diagnosis of polio, which is critical in the diagnostic criteria, will need to be established. This may be difficult because approximately 10% to 15% of individuals who were believed to have or were diagnosed with polio did not have it, and some individuals with mild weakness were diagnosed as having nonparalytic polio.35,71

Boissonnault72 discusses the review of systems as a vital component in the PT’s role in medical screening and differential diagnosis (see Chapter 7). OTs are responsible for this same vital component. Possible multisystem involvement warrants review of all systems to determine if current problems are associated with existing comorbid conditions or occult disease or are indeed late manifestations of the initial disease process, as in the case of polio.

Providing further substantiation for the need for a methodical and multisystem approach are findings of high rates of secondary conditions related to obesity and inactivity common in individuals with developmental disabilities. These secondary conditions include type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and metabolic syndrome, diagnoses that affect multiple systems.17 Individuals with developmental disabilities also have four to six times the preventable mortality of the general population.9,73 As therapists are entering into the decade of becoming primary care providers, anyone with a preexisting functional problem may walk into a PT or OT clinic searching for help. The importance of medical screening cannot be overemphasized.

Tests and measures

Critical to the examination process is the determination of secondary conditions. Secondary conditions have been defined as injuries, body system impairments, functional limitations, or disabilities that occur as a result of a primary condition or pathology15,74–78 as well as physical problems that were caused by small insults to one of the body systems not related to the primary condition. Musculoskeletal problems account for many of these secondary conditions; thus the musculoskeletal examination is of critical importance in individuals with developmental disabilities. Gajdosik and Cicerello77 outlined numerous conditions that may affect the adult with CP; some can lead to significant loss in function and pain from complications such as fractures and osteoporosis. Other musculoskeletal conditions, including scoliosis, subluxations, dislocations, patella alta, foot deformities, pelvic obliquities, and contractures, further complicate the life progression of an adult with developmental disabilities.77 Frequently these chronic conditions may have their origins in childhood, but because of the lack of sensory awareness may go undetected until later adolescence, adulthood, or well into advancing age when the body no longer has the ability to compensate for these abnormal biomechanical forces. Furthermore, as the aging process progresses, less regeneration of damaged tissue occurs, leading to greater cumulative trauma in joints and other load-sensitive structures.78 Again, these conditions need to be closely monitored over time to ensure appropriate intervention, optimizing an individual’s function and minimizing damage to various tissues.

Fatigue

Fatigue is one of the most common symptoms reported by individuals with chronic conditions such as PPS79 and MS.80 Movement and performance of daily activities are more energy consuming for individuals with disabilities and may cause greater fatigue.81 Evidence also points to individuals with disabilities aging faster than those without disabilities; cardiovascular data from individuals with SCI indicate that persons with SCI may age faster than those without SCI.82,83 Cook and colleagues81 identified the lack of age-specific general population norms as an obstacle in the understanding and estimation of the influence of aging on the fatigue of individuals with neuromuscular conditions.

It is likely that that an earlier increase in fatigue with age might be observed in other chronic neuromuscular conditions; however, the effects of chronological age on fatigue in individuals with disabilities are not entirely clear.81 In a recent study, Cook and colleagues81 assessed fatigue and age in four clinical populations of individuals with PPS, SCI, MS, and muscular dystrophy (MD), comparing self-reported fatigue experience in different age cohorts with age-matched, U.S. population norms. A total of 1836 surveys were used in data analysis.

The authors concluded that individuals with disabilities reported higher levels of fatigue than the general U.S. population, regardless of age or disability type.81 Interestingly, the authors noted that the causes of fatigue likely vary by disability type—that is, MS, PPS, and MD are more likely to cause fatigue through a combination of central neurological processes, the effect of sleep disorders such as periodic limb movements (PLMs),84 or increased physical effort, whereas in SCI fatigue may be a side effect of medications or result from sleep disorders.81

Results revealed not only that individuals with disabilities have a higher risk of experiencing fatigue than those without disabilities, but also that the risk for increased fatigue, compared with normative values, increases with age.81 The reported mean fatigue levels were the highest observed in older PPS age cohorts among the disability samples. In the MS group, fatigue was higher than in any other clinical group except PPS. The highest fatigue reported in the MS sample was in the 35- to 44-year-old age cohort, with lower fatigue in older cohorts except for those 75 years of age and older, but the older group had a small sample size. In the SCI group, peak reported fatigue was in the 55- to 64-year-old age cohort. The results for the SCI group younger than 55 years old were very similar to those for the general population.81

In the general population, very little change in fatigue levels for most adults was found moving from young (65 years) to middle (75 years) old age, whereas in the disability samples the authors saw a slight but consistent increase toward greater fatigue at this point in the life span.81 This increase in fatigue could be associated with current physical decline associated with disease progression.81 The authors concluded that more research is needed to determine the specific effects of fatigue on the functioning of persons aging with disabilities and to further explore interventions that may shield against or reduce any negative effects that occur.81

Bruno and colleagues79 state that fatigue has been identified as the most commonly reported, most debilitating, and least studied symptom in the postpolio sequelae. Generalized fatigue is typically described as overwhelming exhaustion or flulike aching accompanied by marked changes in level of energy, endurance, and mental alertness.20 The lack of energy with minimal activity is often described as “hitting a wall,” thus the term “polio wall.” Polio survivors differentiated between the fatigue associated with weakness and a “central fatigue” that leads to attention and cognitive problems.79 Severe fatigue affects not only physical function but mental function as well—hence the controversial suggestion that the fatigue associated with postpolio is caused by impaired brain function rather than the diffuse degeneration of motor units and motor junctions.79

Descriptors for fatigue associated with PPS are significantly different.85 The fatigue of PPS may not appear at the time of the activity, and recovery does not occur with typical rest periods. It has also been described as a sudden and total wipeout. In a few instances headaches and sweating appear, suggestive of autonomic nervous system overload.86 Fatigue commonly occurs in the late afternoon or early evening. Fatigue that tends to last all day is atypical in PPS35 and should alert the therapist to consider other possible diagnoses.

Similar to the fatigue of PPS, MS fatigue profoundly disrupts multiple aspects of general well-being.80 Krupp87 reported that 67% of individuals with MS reported fatigue as a major limiting factor in their social and occupational responsibilities compared with no reports in healthy adults. The fatigue of MS is unique in that it is exacerbated by heat, as are many MS symptoms. Fatigue may be acute, chronic, or intermittent or persistent, whether related to a specific diagnosis such as MS, CP, or polio or having no relation to the initial medical diagnosis. It is necessary to consider the role of other symptoms related to the specific medical diagnosis during the examination of fatigue.

Pain

Individuals with chronic diseases often have pain as a common symptom, most likely from long-term atypical biomechanical forces on joints and muscles or from long-standing disease processes. Many developmental disabilities have a component of disordered movement, from hypomobility in the case of DS to hypermobility in the case of spastic CP. These abnormal joint stresses and strains cause long-term damage to the musculoskeletal system.77,88,89 The natural degradation of joint structures with aging coupled with weakness and atypical ground reaction forces leads to higher incidence of musculoskeletal pain.90–92 Please refer to Chapter 32 for additional discussion of pain.

Joint pain in itself usually results primarily from long-term microtrauma from abnormal biomechanical forces. An example might be the overuse of the shoulder girdle muscles and joint from a lifetime of use of Loftstrand crutches to compensate for lower-extremity impairments after polio. Joint pain is frequently associated with physical activity but is rarely associated with inflammation. Interventions are complicated by the presence of osteoporosis, lack of compensatory substitutions to rest the injured part, and, often, poor response to exercise. Failing joint fusions, uneven limb size, progressive scoliosis, poor posture, and abnormal mechanics may also contribute to pain.93

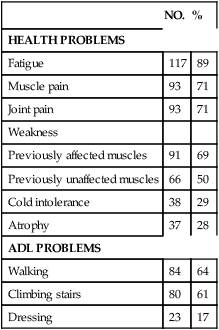

More than 65% of individuals with PPS have reported neck, shoulder, and back pain radiating to the hip and leg.94 This pain is expected because the incidence of major postural abnormalities and gait deviations is also high, as shown in Table 35-1.

Strength

Weakness and postpolio syndrome.

Weakness may occur in both previously affected and clinically unaffected muscles; however, it is primarily prominent in muscles most severely affected in the initial infection.35 It is typically asymmetrical and may be proximal, distal, or patchy.93 Weakness is primarily observed in repetitive and stabilizing contractions rather than with single maximum efforts. The decreased ability of the muscles to recover rapidly after contracting may be a factor. Recovery of quadriceps muscle strength after fatiguing exercise was significantly less in symptomatic PPS subjects compared with asymptomatic and control subjects.95 Overuse of muscles in relation to their limited capacity has long been associated with these new problems.96–98 New weakness and atrophy have been attributed to metabolic overload of the giant motor units, with more pruning of muscle fibers than axon sprouting.99,100

New muscle involvement may also cause signs and symptoms such as muscle fasciculations, cramps, atrophy, and elevation of muscle enzymes in the blood. Yet many of these physical signs and symptoms are also present in other neuromuscular problems such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS; see Chapter 17). Fasciculations occur at rest and during contraction and tend to persist even when muscle pain and fatigue have been resolved. Muscle cramps are common in fatigued muscles and are alleviated by decreased activity. The new weakness may or may not be accompanied by atrophy. New postpolio muscular atrophy of muscles is sometimes reported. It is very noticeable when it occurs in the gastrocnemius or the anterior tibialis owing to the effect on everyday ambulation. Elevation of muscle enzymes, indicative of muscle damage, has been found in individuals with PPS and has been related to the intensity of work.97,101,102

Superimposed pathological problems have been proposed as a possible cause of the later exhibition of new signs and symptoms in postpolio survivors. Several conditions may contribute to weakness, including arthritis, fibromyalgia, deconditioning from disuse, and coronary heart disease.103

Range of motion and muscle length

Box 35-4 lists the secondary conditions that may develop in an individual with CP. These impairments not only cause pain but also limit mobility and interfere with performance of ADLs and leisure activities. Thus a thorough evaluation of musculoskeletal status and periodic monitoring are imperative to maintaining quality of life and social participation for these individuals.

Mobility and posture

Asymmetrical or abnormal gait patterns, crutch walking, and propelling manual wheelchairs for several decades are frequently the major sources of the pain, weakness, and fatigue in people with chronic movement dysfunctions after a medical problem such as TBI, SCI, CP, PPS, or cerebrovascular accident (CVA). The incidence of pain in a group of 114 patients with confirmed PPS increased from 84% in those who were ambulatory without orthotics to 100% in those who used crutches or wheelchairs for locomotion.94 A high prevalence of osteoarthritis in patients with PPS was documented in the hand and wrist by radiography.104 More than twice the number of subjects with PPS had osteoarthritis of the wrist or hand than would be expected in a healthy population of the same age. The risk factor was significantly increased with lower-extremity muscle paralysis and use of assistive devices.

In an electromyographic study of walking in clients with PPS, Perry105 demonstrated overuse and substitution activity of the vastus lateralis, biceps femoris, and gluteus maximus muscles when the soleus is nonfunctional. Such substitution and overcompensation in the long term, however, lead to microtrauma of ligaments and joint structures and exhaustion of neuromuscular units.

Environmental temperature intolerance

Regulation of body temperature is often a problem for individuals with MS (see Chapter 19). Earlier, it was noted that a feature of fatigue unique to MS is that the fatigue is exacerbated by heat. Other MS symptoms may also be aggravated by heat. The Uthoff phenomenon106 is an adverse response to external heat, causing fatigue or deterioration of symptoms; it often occurs with exercise. Specific recommendations for cooling during exercise intervention may be necessary to counteract the deleterious effects of heat. It is important that the examiner meticulously determine during the health interview the symptomatic effects, if any, of increased temperature in the aging individual with MS.

Sensory deficits per se are not hallmark features of polio; however, cold intolerance is a commonly reported late-onset symptom. Involved extremities in individuals with PPS are frequently abnormally cold as a result of sympathetic nerve cell involvement leading to decreased vasoconstriction and venoconstriction with heat loss to the environment.107 The impairment may become worse with PPS. Environmental adaptation can create an easy solution to this problem as long as the individual with PPS is aware first of the problem and second of the adaptations necessary to avoid thermoinstability within the extremities. Preventing versus responding to the inadequate vasoresponse to cold empowers the individual to develop environmental control.

Sleep disturbances

It is common knowledge that elderly individuals report and manifest sleep disorders.108,109 Thus, this body system problem certainly can be associated with aging individuals with chronic movement dysfunction. Disturbances in sleep are a common symptom in persons with chronic neuromuscular diseases. Sleep deprivation is a contributing factor to fatigue in individuals with MS. Similarly, more than 50% of individuals with PPS have been found to have sleep disturbances.110 These disturbances may be caused by pain, stress, hypoventilation, or obstructive apnea.111–113 Bruno114 proposed a high incidence of abnormal movements in sleep in nearly two thirds of polio survivors, with 52% reporting sleep disturbance caused by these movements. All seven of subjects with PPS in the study demonstrated abnormal movements in sleep. The author points to the importance of eliminating sleep disorders as a cause of fatigue before the diagnosis of postpolio sequelae is made, particularly because it remains a diagnosis of exclusion.114

In addition to the typical symptoms of muscular weakness, pain, and fatigue associated with PPS, some individuals also develop sleep disorders such as periodic limb movements (PLMs).84 PLMs in sleep are repetitive episodes of muscular contractions with durations of 0.5 to 5 seconds; frequencies of five or more per sleep hour are deemed pathological. The association of PLMs with insomnia or daily sleepiness suggests the diagnosis of PLM disorder.84 Whereas PLM has been related to the pathophysiology of PPS,114 the occurrence of PLM in PPS is not well known.84 In a recent retrospective study of 99 patients with PPS, researchers assessed the frequency of PLMs during sleep, including other sleep-quality variables such as total sleep time, efficiency of sleep, apnea-hypopnea index, and awaking index.84 Sixteen patients showed a PLM index that was considered pathological. The authors concluded that a close relationship between PLM and PPS exists; however, the prevalence of PPS with or without PLM and its combination with apnea-hypopnea is not clearly established, a finding in agreement with the conclusions of Jubelt and colleagues.84,115

Life-threatening conditions

In the case of PPS, bulbar muscle dysfunction93 may also result from the new weakness. Life-threatening conditions such as hypoventilation, dysphagia, sleep apnea,116 and cardiopulmonary insufficiency require management by medical specialists.111,117,118 These problems occur in people with previous bulbar poliomyelitis who may or may not be using ventilatory assistance and in those with severe kyphosis or scoliosis. Respiratory failure may occur primarily in individuals with residual respiratory insufficiency and minimal reserves.115

Functional assessment

Performance in functional activities often provides a better picture of the losses stemming from chronic impairments. Decreases in strength are not usually revealed in a single-effort maximum contraction such as required in the manual muscle test. Resistive force during testing is a necessary element for two grades, 5 (normal, “N”) and 4 (good, “G”), whereas the other four grades are nonresistive and mostly nonfunctional, and few examiners are now tested for reliability.119 In a 1-year follow-up using quantitative muscle force testing, no differences were found in muscle strength, work capacity, endurance capacity, or recovery from fatigue of the quadriceps in either asymptomatic or symptomatic groups with PPS.120 Nevertheless, there is at best a slow decline in functional ability, which clients may describe as loss of muscle strength. Clinically, individuals seeking therapy report functional loss or limitation more easily than a specific loss of muscle strength.

Functional assessment of individuals with chronic movement limitations provides a more practical and clearer picture of the abilities and limitations related to the initial condition or stemming from new impairments. Functional activities are visible and reportable performances of relevant tasks in the context of the individual’s culture.121 Functional tasks imply a specific goal and can range from simple to complex activities. In functional motor performance, the specific task and environmental context is as important as the individual functional movement (refer to Chapter 8). Consideration for these factors is necessary during examination. Detailed functional assessment is outlined by Howle122 and Zabel.123

Decreases in functional activities over time for varied chronic conditions35,45–49,124 have been documented in the literature. As early as 5 years and up to 20 years after the initial SCI, individuals have reported decreases in functional activities and increased need for assistance with ADLs.45–48 An association with the need for increasing support with advancing age in individuals with SCI is seen in the literature.45–47

According to Agre and Rodriquez,125 postpolio survivors with significant weakness perform daily activities at a different level of effort than other individuals; muscles of polio survivors may have to work near maximal effort during activities that individuals without polio can execute at relatively lower levels of effort. Individuals with PPS commonly report difficulty in walking, stair climbing,35 and dressing (Table 35-2). Westbrook124 described a 5-year follow-up study examining physical and functional abilities and health status of 176 individuals with PPS. During the course of the study, most subjects reported increases in muscle weakness, muscle and joint pain, and changes in walking. Notably, the participants reported more difficulty in four of the eight daily living activities (stair climbing, walking on level surfaces, transfers in and out of bed, and meeting the demands of home or work). Most of the participants (87%) also reported problems in meeting the demands of their job and completing household tasks. Clearly, the ability to perform motor tasks essential to completing one’s goals and desires is multifactorial. Therefore, functional limitations are usually related to a combination of systems impairments.

TABLE 35-2

| POSTURE | ABNORMAL DEVIATION | NO. | % |

| Sitting (n = 111) | Absent lumbar curve | 64 | 54 |

| Forward head (loss of cervical curves) | 50 | 45 | |

| Uneven pelvic base* | 29 | 26 | |

| Structural scoliosis | 38 | 34 | |

| Standing (n = 76) | Absent lumbar curve | 52 | 68 |

| Uneven pelvic base* | 40 | 53 | |

| Weight bearing on stronger leg | 29 | 38 | |

| Walking (n = 76) | Abnormal gait deviations | 76 | 100 |

| Major lateral trunk oscillations | 33 | 43 | |

| Obvious forward lean | 40 | 53 |

*Pelvic asymmetry was ½ inch or more.

Modified from Smith L, McDermott K: Pain in post-poliomyelitis: addressing causes versus effects. In Halstead L, Wiechers D, editors: Research and clinical aspects of the late effects of poliomyelitis, White Plains, NY, 1987, March of Dimes.

In persons with PPS, to determine whether the cause of the new weakness is overuse or possibly disuse, a detailed assessment is required of home, work, recreational, and community activities.126 This paradigm of multidimensional assessment is applicable to all individuals with chronic movement problems. If the client is merely asked what his or her activity level is, the response may lead to assumptions that weakness is from disuse. With specific questioning, one usually finds that the client is doing an extraordinary amount of physical activity. It is vital to establish a total picture of the client’s activities in sitting, standing, walking, lifting, carrying, climbing stairs, using a telephone or a computer, and performing daily activities such as self-care and home management.

Psychosocial considerations

Over the past years, several authors have addressed the prevalence of PPS, its causes, and the effects of aging on the development of PPS.* Some literature addresses the effects of aging on developmental and genetic disabilities, yet information on how aging affects individuals with existing impairments is still not conclusive. Because persons who are aging with chronic disabilities is an emerging population owing to improvement in health care delivery and nutrition, evidence on the consequences of the aging process remains uncertain. Similarly, the psychological effects are not as widely addressed in the literature. Not much is known about the quality of life of older adults with congenital or childhood-acquired disabilities. Psychological adjustment is difficult with any disease with an unpredictable course, and differentiating organic psychological problems from adjustment issues may complicate the management of individuals with chronic diseases.

Postpolio syndrome

Although the physical manifestations of and interventions for PPS are recognized, psychological symptoms become evident in polio survivors. Bruno and Frick37 described psychological symptoms such as chronic stress, depression, anxiety, compulsiveness, and type A behavior in polio survivors; these symptoms not only cause distress but limit these individuals in making lifestyle changes to manage late-onset symptoms. Currie and colleagues103 made generalizations about adults with childhood-onset or congenital disabilities spanning a range of disability types. Understanding the background of individuals with PPS and a few of the myths that helped to shape their lives is beneficial in their care. Fear of the disease was rampant during the early epidemics. Despite safety measures, children and adolescents contracted polio. Part of the coping strategy was encouraging the child to high levels of physical achievement; approval and rewards were gained by walking farther or faster and keeping up with or exceeding the performance of other children. The best treatment available for all polio victims at that time was from the March of Dimes, which entailed hospitalization for months at a time away from the individuals’ families and communities. The situation led to feelings of abandonment, anxiety, and total dependence on strangers. The “polio patient” was expected to be a “good patient” and to “work hard.” Indeed, these patients did work hard to reeducate weakened muscles and compensate for lost function.37–40 Courage, determination, and cheerfulness were attributes to be prized, self-pity was viewed unfavorably, and talking about the functional loss was not encouraged. Later in the recovery process, parents made decisions to have their children undergo multiple surgical procedures to allow removal of heavy braces so that they would “look normal” and “fit in.” One can understand why clients react so negatively to the suggestion of orthotics.

Coping strategies

The psychosocial issues confronting persons with PPS often are more disruptive than the physical problems.22,23,71,132–134 An increasing population of polio survivors is experiencing, with aging, an unanticipated late onset of new symptoms. Associated with loss of physical function and independence are social and psychological problems stemming from the inability to perform personal and societal roles. Previous research suggests that well-established, often compulsive behavior patterns may impair the ability to deal effectively with the new threats to functional independence. Bruno and Frick24 confirmed the presence of psychological stress in survivors, noting that type A behavior and stress could precipitate or exacerbate postpolio sequelae. In a later study in 199137 the same researchers suggested that the acute experience conditioned survivors into lifelong patterns of compulsive type A behavior, a behavior pattern that impairs the ability to cope with new late postpolio symptoms. Kuehn and Winters135 also noted that symptom distress and intensity were less in individuals with greater coping resources. In this study135 in Sweden of 113 patients with postpolio sequelae, results revealed that the prevalence of distress was highest in the physical dimensions of physical mobility, pain, and energy and lowest in social isolation. The high scores for the triad of dimensions were similar to the findings of previous studies.116

Individuals with PPS developed several styles to cope with their disability. Maynard and Roller136 described coping styles according to severity of muscular involvement. Survivors with little or no obvious physical involvement were able to hide atrophy with clothing and avoided activities that revealed the weakness. Many individuals invested much energy in projecting normality and were so adept at denial that they disconnected themselves from the polio experience; often spouses do not know of the history of polio. This group can develop the most severe cases of PPS. The denial renders them detached from other individuals with PPS and thus difficult to assist.

In a 5-year study of 176 individuals with PPS, it was unexpectedly found that participants’ stress levels decreased over time.124 The author hypothesized that eventually, lifestyle modifications and treatment contributed to the coping process. Kuehn and Winters135 in their study found that more than half of their subjects of working age had gainful employment. Moreover, no difference in employment rate as a result of distribution of polio involvement was found, implying that this was not a deciding factor. The authors hypothesize that persons with severe polio involvement were either forced to choose or encouraged to take up an appropriate profession early in life, whereas those with less involvement had not needed such planning. Nevertheless, vocational issues encompassing satisfactory accessibility and equipment are an important part of management.

Response to new diagnosis.

The response to the diagnosis of PPS can range from relief to despair. Relief comes to polio survivors who have been told their symptoms were psychosomatic. Despair occurs when survivors are given a program of lifestyle changes and management suggestions that are opposed to the adage they followed during the initial infection. The proposed philosophy shift from “no pain, no gain” to energy conservation and rest may be viewed unfavorably or with disdain. Polio survivors who have led active lives may have significant difficulty adjusting their lifestyle to new symptoms and decreasing abilities, and psychological support may be indicated.137

The stresses of the diagnostic process also add to the challenges. Most health care professionals have limited understanding of the initial polio experience and the late effects of polio, and therefore the diagnostic process of PPS may take time and involve a series of physician consultations.37,38,138–140 Publicity from support groups has helped refer clients to PPS clinics or to specialists with knowledge of PPS.140

Fear of the threat to independence, inadequate knowledge about the physiological changes, and the expectation of functional loss may contribute to the anxiety of polio survivors. Individuals with PPS will feel anxious about the prospects of changing roles with their families, friends, and co-workers.38,136,139 Defenses and coping strategies that have been successfully used for years have broken down, and the individual experiences overwhelming anxieties and conflicts.139

Compliance.

The patient-clinician relationship is an important determinant of compliance. Several authors24,37,141 have identified compliance as a significant problem in type A polio survivors. Although a few individuals with PPS readily accept suggestions for lifestyle changes, a few immediately make changes, and a few refuse to consider any changes at all, most will eventually make changes but will require support, patience, and time to process. Compliance is an issue encountered not only in individuals with PPS but in many individuals with chronic conditions. Clinicians’ sensitivity, support, and respect will play a major role in the response of the patient/client to management suggestions. Acknowledging the individual’s current activities, values, and goals is an important step in establishing a relationship with the patient/client. Allowing clients to express feelings about the new challenges, their prior high levels of physical achievement, and previous treatment is equally important.

A health care provider perceived to be knowledgeable, interested, and concerned significantly increases compliance with recommendations.142 Compliance of the client with PPS may be improved by the therapist’s ability to suggest management strategies that are accepted as conventional and the ability to alleviate pain in the initial examination. Conservative management should be attempted first before more aggressive or life-changing interventions such as orthoses, mobility changes, or motorized carts, which they may have used in the past and eventually discarded. Therapists can also be a source of information about support groups.140 Support groups offer information about every facet of living with chronic impairments, and these members may be positive role models to help not only the newly diagnosed individual in the transition process but also the aging individual with chronic disease and impairments deal with issues with maturation and advancing age.

Health-related disparities in aging adults with chronic disabilities

Individuals aging with chronic impairments and conditions are exposed to the effects of aging and maturation differently than the general population. Persons with disabilities often start at the lower end of the health continuum owing to secondary conditions that overlap with the primary disability.143 Few will argue that despite medical advances and public health initiatives, the reality is that health disparities, including decreased access to high-quality health care, health promotion, disease prevention, and health literacy, are still present and reflect areas that need to be addressed. Outlined here are some health disparities facing adults with chronic disabilities and conditions.

Compared with the general population, higher rates of disability and obesity are seen among adults with developmental delay.66,144,145 Of adults with major physical and sensory impairments, 27% are obese, compared with 19% of those without major disability.68

Compared with the general population, higher rates of disability and obesity are seen among adults with developmental delay.66,144,145 Of adults with major physical and sensory impairments, 27% are obese, compared with 19% of those without major disability.68

Cardiovascular disease is one of the most common causes of death among aging adults with developmental delay.17,146,147

Cardiovascular disease is one of the most common causes of death among aging adults with developmental delay.17,146,147

Evidence supports the earlier appearance of age-related health conditions in individuals with developmental delay. Conditions include cognitive decline, incontinence, and sensory losses.148 Examples of health conditions that may be influenced by aging in persons with developmental delay were discussed earlier regarding individuals with CP149 (who may have increased issues with musculoskeletal deformities, progressive cervical spine degeneration, dental problems, bladder or bowel dysfunction, or osteoporosis) and individuals with DS (who have a higher prevalence of early-onset Alzheimer disease compared with the general public).13,150

Evidence supports the earlier appearance of age-related health conditions in individuals with developmental delay. Conditions include cognitive decline, incontinence, and sensory losses.148 Examples of health conditions that may be influenced by aging in persons with developmental delay were discussed earlier regarding individuals with CP149 (who may have increased issues with musculoskeletal deformities, progressive cervical spine degeneration, dental problems, bladder or bowel dysfunction, or osteoporosis) and individuals with DS (who have a higher prevalence of early-onset Alzheimer disease compared with the general public).13,150

Generally, individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities have poorer health and more difficulty in finding, accessing, and paying for higher-quality health care.7

Generally, individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities have poorer health and more difficulty in finding, accessing, and paying for higher-quality health care.7

Adults with developmental disabilities also have limited access to medical care, which may result in lack of obesity screening, counseling, and management.151

Adults with developmental disabilities also have limited access to medical care, which may result in lack of obesity screening, counseling, and management.151

Higher rates of depression, anxiety, and strong fears and stress are seen in persons with chronic disabilities. Iezzoni68 found that 34% of adults with major impairments in walking reported frequent depression or anxiety, compared with 3% in those without disabilities.

Higher rates of depression, anxiety, and strong fears and stress are seen in persons with chronic disabilities. Iezzoni68 found that 34% of adults with major impairments in walking reported frequent depression or anxiety, compared with 3% in those without disabilities.