CHAPTER 59 Management of Atypical and Anaplastic Meningiomas

INCIDENCE AND PREVALENCE

The annual incidence of meningioma is approximately 6 per 100,000.1 These tumors occur mostly in middle-aged or elderly patients, but they can also occur in younger patients, mainly with neurofibromatosis type 2. Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas represent a small subgroup with histologic and clinical features suggesting aggressive behavior. Owing to the lack of one clear histopathologic classification in the past, there are numerous inconsistencies in the literature. Therefore the rates of atypical and anaplastic meningiomas reported in the literature vary considerably, ranging from 4.7% to 19.8% for atypical and from 1% to 7.2% for anaplastic tumors.1–8 It is known that the prevalence of benign meningiomas is higher in women. In atypical meningiomas there is an equal male:female ratio2,9,10 or even a slight female predominance.11,12 In contrast, anaplastic meningiomas seem to be more common in males.7,9,13,14 Further, atypical and anaplastic meningiomas appear earlier in life.9,13

Most studies either do not present exact data about the location of atypical and anaplastic meningiomas or mix the two types of tumors. Looking at the reported cases one can say that atypical meningiomas are located in 65% over the convexity, the falx, or the parasagittal region, in 31% on the skull base, in 2% on the tentorium, and in 2% in the posterior fossa.3,9–11,15–18 For anaplastic meningiomas, the percentages change to 77% (convexity, falx, and parasagital), 18% (skull base), 3% (tentorium), and 2% (posterior fossa).1,4,9,10,15,16,18–26 Sade and colleagues reported that 75% of atypical and 80% of anaplastic meningioma are found over the convexity and 25% and 20% respectively on the skull base.27 There are only a few reports of atypical and malignant spinal meningiomas, suggesting that tumors in this location have a different pathologic behavior as they rarely show malignant transformation or recurrence even if not totally resected.27–29 The differential meningeal embryogenesis may result in the predominance of one arachnoidal cell type over the other at certain location.27 Metastases for meningiomas are rare, even for anaplastic meningiomas. The lungs are the most common site for seeding but metastases were also found in the bone, liver, skin, and subcutaneous tissue.12,29–31

Atypical and anaplastic meningioma can occur after cranial irradiation for tumors or other conditions, especially in younger patients.32 It is reported that 2% of patients with a meningioma have a prior history of high-dose radiotherapy for intracranial neoplasm, including pituitary adenomas, medulloblastomas, astrocytomas, and acoustic neuromas.12,33 The incidence of 76% benign, 19% atypical, and 4% malignant among radiation-induced meningioma with high-dose therapy and 90% benign and 10% atypical after low-dose radiotherapy is reported.34 As radiation-induced atypical and anaplastic meningiomas show a different clinical course and seem to have different pathologies they are discussed in Chapter 4.

PATHOLOGY

As mentioned, the histopathologic classification or grading of atypical and anaplastic meningioma has been a topic of debate. At present, most studies refer to the 2000 WHO criteria for their classification, which have not changed with the 2007 edition (Table 59-1).14

TABLE 59-1 Classification and grading of meningiomas according to the histological subtype14

| Grade I (benign) | Grade II (aggressive) | Grade III (malignant) |

|---|---|---|

| Meningothelial | Atypical | Anaplastic |

| Fibrous (fibroblastic) | Clear cell | Rhabdoid |

| Transitional (mixed) | Chordoid | Papillary |

| Psammomatous | ||

| Angiomatous | ||

| Microcystic | ||

| Secretory | ||

| Lymphoplasmacyte-rich | ||

| Metaplastic |

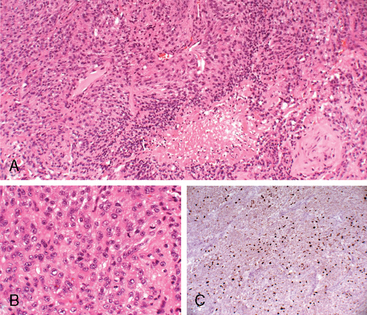

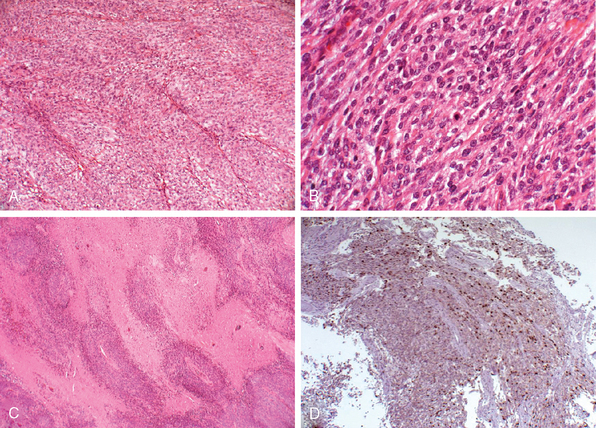

Meningiomas are classified as the atypical type if they show increased mitotic activity or three or more of the following histologic features: increased cellularity, small cells with a high nuclear: cytoplasmic ratio, prominent nucleoli, uninterrupted patternless or sheet-like growth, and foci of “spontaneous” or “geographic” necrosis. Increased mitotic activity is defined as 4 or more mitoses per 10 high-power (40×) fields (defined as 0.16 mm2) (Fig. 59-1). Anaplastic meningioma exhibit histologic features of frank malignancy far in excess of the abnormalities present in atypical meningioma. These include either obviously malignant cytology resembling that of carcinoma, melanoma or high-grade sarcoma, or a markedly elevated mitotic index of 20 or more mitoses per the high-power fields (defined as 0.16 mm2) (Fig. 59-2).14 Brain invasion, characterized by irregular, tongue-like protrusions of meningioma cells infiltrating underlying parenchyma, without an intervening layer of leptomeninges, connotes a greater likelihood of recurrence and can occur in histologically benign, atypical, and anaplastic meningioma. It is estimated as an adverse prognostic factor for tumor recurrence and is associated with a significant decrease in survival.35,36

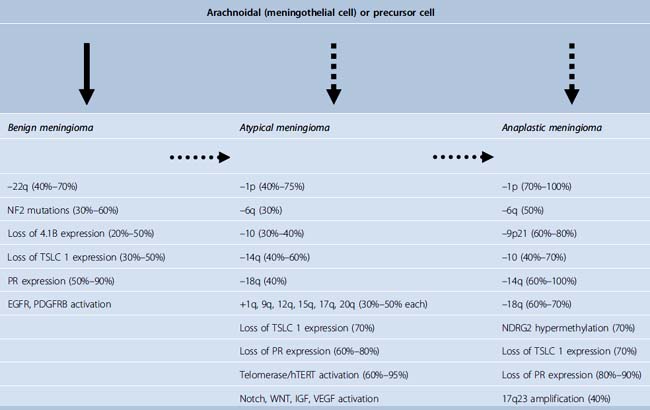

The clinical course and prognosis of atypical and anaplastic meningiomas seem to be heterogeneous.9,10 For example, the clinical behavior of radiation-induced meningiomas differs from similar meningiomas of the same pathologic grade.32 A differentiation or “de novo” atypical and anaplastic meningiomas versus meningiomas with progression has been proposed, as they seem to have different clinical courses.9,35 It is accepted that atypical and anaplastic meningiomas evolve by the accumulation of cytogenetic aberrations and that subsequent genomic changes result in a poorer clinical outcome. The hormone receptor status may also play a role in predicting the outcome. Therefore, a future classification may consider genetic as well as hormone receptor studies as part of the diagnosis.

PROGRESSION

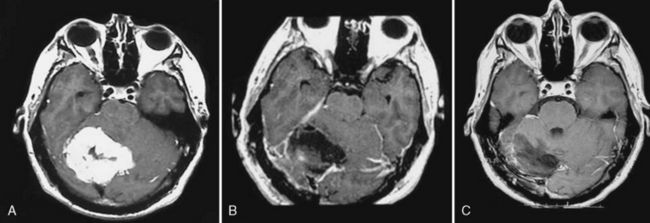

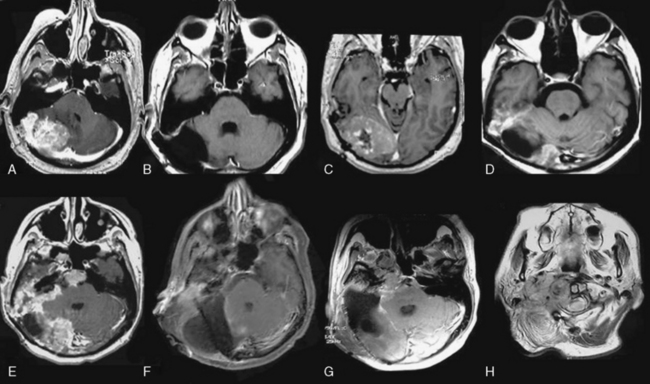

Meningiomas can progress from benign to atypical or anaplastic variants, as is well documented with gliomas.1,2,4,9,24,35 This phenomenon, in which a neoplasm changes irreversibly in one or more characteristics, has been termed tumor progression.37 Such a biologic and clinical progression reflects the sequential appearance of cytogenetically acquired changes.38,39 Glioblastomas can develop de novo or progress from a low-grade or anaplastic astrocytoma termed primary and secondary glioblastoma.14,40 Recently, the differentiation of such “de novo” and “transformed” types of atypical and anaplastic meningiomas has been proposed as they show a significant different overall survival.9,35 Between 0.16% and 2% of all meningiomas experience malignant progression, and the rate of progression in recurring tumors is higher in atypical than in benign meningiomas.2,4,10,24,35,41 Up to 28.5% of recurrent meningiomas transform to malignant varieties,1,2 and the risk of progression from atypical to malignant ranges from 26% to 33%.4,10 The period of time that elapses between the appearance of a tumor and its progression to malignancy is variable. Some describe it shorter for tumors progressing to the anaplastic variant than for tumors progressing from benign to atypical.2 Yang and colleagues found a mean period for malignant progression of 70.0 months from benign to atypical meningiomas and of 89.7 months from benign to anaplastic meningiomas.35 The period of progression from atypical to anaplastic is described to be considerably shorter (39.8 months),35 a fact that is confirmed by other studies.9 Tumors with malignant progression occur in atypical meningiomas in 35% to 38% and in 65% to 70% of anaplastic meningiomas. On the other hand, “de novo” atypical meningiomas occur in 62% to 75% in atypical and 25% to 30% in anaplastic meningiomas.9,35 Meningioma located over the convexities or of the parasagittal location seem to progress more often to malignancy than meningiomas of the skull base.9 The average number of operations performed in meningiomas with malignant progression is higher than in “de novo” aggressive meningiomas, which is due to their more aggressive behavior (Figs. 59-3 and 59-4).

Several studies show that progression in meningioma is associated with cytogenetic alterations and changes in the hormone receptor status, which might also be markers of malignant potential that influence tumor recurrence and poor prognosis.2,42–45

HORMONE RECEPTORS AND PROLIFERATION INDICES

Progesterone receptor expression in meningiomas relates to the tumor’s grade and recurrence. A progesterone receptor–positive status is more frequent in benign than malignant tumors46–48 and there is an association between recurrence and progesterone receptor–negative status.49 Overall survival and tumor recurrence in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas seem to be associated with a high Ki-67 labeling index.50 But significant overlap exists in the ranges for benign, atypical, and anaplastic meningiomas.51 Proliferative indices in progesterone receptor–positive meningiomas are lower than those in progesterone receptor–negative tumors.47,52 Thus, negative progesterone receptor and a higher mitotic activity indicate more aggressive behavior.43,46–49,52 Atypical meningiomas with progression from a benign tumor often have negative progesterone receptor and a higher proliferative index, which may explain the more aggressive behavior than the de novo atypical meningioma.9 Estrogen receptors seem to be more present in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas.43,52

GENETICS

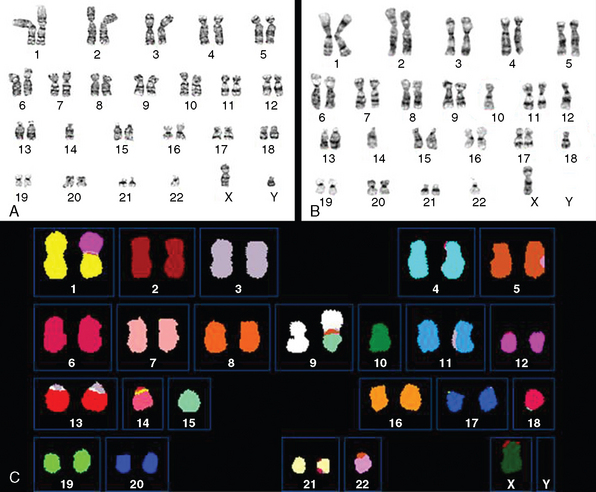

Genetic alterations in meningiomas are known to increase as the tumors become more aggressive.45,53,54 In general, karyotypic abnormalities are more extensive in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas including multiple translocations between different chromosomes and monosomy of multiple chromosomes. In addition to abnormalities of the chromosome 22, which were among the first cytogenetic alterations recognized in solid tumors,14 alterations of chromosomes 1, 6, 9, 10, 14, 16, 18, 19 and sex chromosomes are most often detected in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas.44,53–60 Partial loss or monosomy of chromosomes 1, 10, and 14 is associated with more aggressive behavior in meningiomas.53,54,60–70 Loss of chromosome 18 and loss of part or monosomy of chromosome 10 and an increased monosomy or derivative chromosome 1 in combination with monosomy of chromosome 14, which may represent a bad prognosis, occurs more frequently in meningiomas with progression9 (Fig. 59-5). Two of the most frequent early events in meningioma tumorigenesis involve the loss of expression of the neurofibromatosis 2 (NF2) and 4.1B genes. The 4.1B gene is shown to interact with the tumor suppressor in lung cancer-1 (TSLC1) protein expression, which was shown to be absent in 48% of benign, 69% of atypical, and 85% of anaplastic meningiomas.71 Overexpression of p53, which is probably a surrogate for p53 mutations,72,73 is described to be a predicting factor for the progression in meningioma.35,74,75 It is known that the expression of several genes linked to cell cycle regulation are up-regulated in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas and that expression of several members of the insulin-like growth factor (IGF) and wingless (WNT) signaling cascade is increased in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas with loss on chromosomes 10 and 14, suggesting that aberrations of these pathways may also play a role in progression.76 Cai and colleagues found that the combination of the deletion of 1p and 14q correlated with decreased survival in patients with atypical meningiomas.62 The WHO 2007 classification determines a stepwise change in the genetic characteristics of benign meningioma, as these become anaplastic (Table 59-2).14

IMAGING

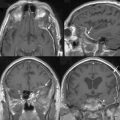

To date there is no specific imaging modality to diagnose atypical or anaplastic meningioma. Several features on their appearance in computed tomographic (CT) scanning have been described, but all of them are nonspecific and can also be seen in benign meningioma: marked edema, heterogeneous appearance, homogeneous dense contrast enhancement, irregular or nodular cerebral surface, mushrooming on the outer edge of the lesion, bone destruction, and absence of calcification.1,4,13,77 But CT still has a role to define the extent of bone invasion in preoperative planning.

Unfortunately, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) does not allow a precise diagnosis either.78 But recently, perfusion MRI was evaluated to differentiate benign and malignant meningiomas on the basis of the differences in perfusion of tumor parenchyma and/or peritumoral edema by measuring the cerebral blood volume (rCBV) and the corresponding relative mean time to enhance (rMTE) (in relation to the contralateral normal white matter) in both tumor parenchyma and peritumoral edema.79 Statistical significance was found only in the rCBV and rMTE in peritumoral edema with higher values in malignant meningiomas. Also, diffusion-weighted MRI findings of atypical/malignant meningiomas and benign meningiomas differ. Atypical/malignant meningiomas have lower intratumoral apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values than typical meningiomas. Mean ADC values for peritumoral edema do not differ between benign and atypical meningiomas.80,81 Magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS), which helps in the diagnosis and differentiation between lesions on MRI, has also been used to distinguish higher grade from benign meningiomas. But no specific spectral characteristics could be found for these subtypes of meningiomas,82 except for a peak in lactate and a probable increased choline/creatine ratio in higher-grade meningiomas.83,84

SURGICAL TREATMENT

The grade of surgical resection of all types of meningioma is the most important prognostic factor for recurrence.1,30,85–88 It allows definitive diagnosis and reduces the mass effect. As with benign meningiomas, the surgical excision should be as complete as possible, including if possible a margin of the dura mater around the tumor, any infiltrated soft tissue, and the bone infiltrated by the meningioma. The likelihood of gross total resection varies considerably by primary sites.89 Careful preoperative planning should include MRI in combination with MR angiography/venography if needed to evaluate dislocation and stenosis of parent vessels and the pattern of venous draining. CT scan should be performed for the evaluation of bony infiltration by the tumor. Digital subtraction angiography should be used if the arterial or venous system cannot properly be evaluated by MRI or if a revascularization procedure is considered during surgery. As “the first time is the best time,” the first surgery is the most important one, especially in higher-grade meningiomas. In further operations, a complete excision is becoming more difficult without significant morbidity because most patients underwent high dose or stereotactic radiation therapy, which in combination with a lack of an arachnoidal plane leads to significant adhesion of the meningioma to the brain parenchyma and the surrounding neurovascular structures. It is described that, once recurrence develops, prognosis is poor because of a high likelihood of treatment failure.12,90 In skull-base atypical and anaplastic meningiomas, appropriate skull-base approaches should be used for better exposure of the tumor. It should allow early devascularization of the tumor, removal of infiltrated bone, less or no brain retraction, and a short working distance. Rarely preoperative embolization is needed in these cases, but the decision should be made on a case-by-case basis. Eventually cerebral revascularization with a bypass should be considered if tumor infiltration of the wall of the internal carotid artery is presumed or if a total tumor excision is achievable only with the sacrifice of an important vessel.

RADIATION THERAPY

Historically, meningiomas were considered resistant to irradiation. Moreover, there has been apprehension regarding the malignant degeneration of irradiated tumors a well as about the relationship between irradiation and the ultimate development of meningiomas.89 The effect of radiation therapy on atypical and anaplastic meningioma is difficult to analyze. Because of the small numbers, a distinction between these two types is often not made. Moreover, because of the variation of histopathologic classification, a comparison of the different studies is difficult. Unfortunately, the exact grade of resection is often lacking or imprecise.

Conventional Fractionated Radiation Therapy

Although there is no prospective study to compare early postoperative radiation with radiation of recurrent tumor, the consensus in the literature favors early fractionated radiation therapy.7 The largest series of 119 patients with atypical and anaplastic meningiomas shows 5- and 10-year overall survival rates of 65% and 51%, respectively, with age greater than 60 years (P = 0.005), Karnofsky performance status (P = 0.01) and high mitotic rate (P = 0.047 being significant factors for the outcome.31 The grade of surgical resection in this study was not a significant prognostic factor, probably due to the difficulty to retrospectively assess the completion of resection.31 Others show significantly better outcome in patients with gross total resection and adjuvant radiation therapy.10 Goyal and colleagues showed a local tumor control of 87% at 5 and 10 years with external beam radiation therapy in 8 patients with atypical meningioma after gross total resection.3

Stereotactic Radiosurgery

The role of stereotactic radiosurgery is nowadays well defined for benign meningiomas. For higher-grade meningiomas, most studies report fairly good results with low complications. Local tumor control in atypical meningiomas is described to be between 64% and 68% at 5-year follow-up.91,92 Others report a 3-year survival rate associated with atypical and anaplastic meningiomas to be 24.4 and 13.9 months, respectively.93 Harris and colleagues reported their treatment results for 18 atypical and 12 anaplastic meningiomas that had undergone radiosurgery. Patients with atypical meningiomas had 5- and 10-year survival rates of 59%, whereas those with anaplastic meningiomas had rates of 59% and 0%, respectively.94 Ojemann and colleagues treated 37 lesions in 19 patients with recurrent atypical and anaplastic meningioma with 2- and 5-year progression rates of 48% and 34%, respectively.22

Brachytherapy

Brachytherapy may play a role in the therapy of atypical and anaplastic meningioma, but the data available in the literature are limited. Ware and colleagues reported 22 patients with recurrent atypical and anaplastic meningioma who were treated with surgery and brachytherapy with implantation of I-125 into the tumor bed.95 The median survival was 2.4 years, but 27% showed wound problems.

Proton Beam Therapy

Proton beam therapy seems to be promising, as it allows high dosages of radiation delivery to region near critical structures, but it has limited availability and its costs are high. Moreover, there are implicit limits to the size of tumor that can be treated. The delivery of higher target doses by 3D-treatment planning assisted combined photon and proton beam therapy with target doses greater than 60 Gy significantly improved local control rates and survival.12,96 Especially in atypical and anaplastic meningiomas, proton beam therapy should be considered because other treatment modalities have a high failure rate.

CHEMOTHERAPY

The role of chemotherapy in the treatment of atypical and anaplastic meningiomas remains unclear. Several chemotherapeutic agents have been used, mainly for meningiomas with progression or recurrence after radiotherapy or for unresectable tumors. The use of conventional chemotherapy with intravenous cyclophosphamide, Adriamycin, and vincristine as well as the treatment with interferon α-2B showed moderate success and the use of Tamoxifen has been shown to be ineffective.97 The use of the antiprogesterone agent mifepristone (RU-486) was first thought to be successful in stabilizing the disease, but in a phase III placebo-controlled trial no significant evidence of activity was found.98

Hydroxyurea, which inhibits meningioma cell growth in vitro by causing apoptosis, has been used as a treatment for recurrent and rapidly growing meningiomas.97 It has shown modest clinical activity against inoperable or recurrent benign meningioma with clinical and radiologic stabilization, but it is probably ineffective in higher-grade meningiomas.7,97 Novel therapeutic drugs such as antiplatelet derived growth factors and antiepidermal growth factor compounds are under investigation and may be used in the future for atypical and anaplastic meningiomas.7

OUTCOME

It is difficult to give clear answers about the clinical outcome of atypical and anaplastic meningiomas because in numerous studies they were combined for outcome analysis or no clear differentiation was made between the two types owing to the small number of tumors. Median survival time for anaplastic meningioma is described by Perry and colleagues to be 1.5 years, with a 5-year mortality rate of 68%.99 Yang found that the median survival rate for anaplastic meningiomas is 39.8 ± 7.8 months, and the 3- and 5-year survival rates are 55% and 35%, respectively.35 The mean overall and mean recurrence-free survivals in atypical meningiomas are reported to be 142.5 ± 6.0 months and 138.5 ± 7.0 months, respectively.35 Krayenbühl and colleagues reported an overall average survival time for patients with atypical and anaplastic meningiomas to be 4.54 years (range 0.07–15.95 years) and 1.48 years (range 0.18–13.26 years), respectively.9 Recently differences in outcome in “de novo” atypical and anaplastic meningiomas and tumors with malignant progression were found.9,35 Overall survival and recurrence-free survival are significantly worse in patients with malignant progression than in those without malignant progression (P = 0.007 and P = 0.005, respectively).35 The average survival time for patients with “de novo” atypical meningiomas was 5.36 years (range 1.02–15.95 years) compared with 1.95 years (range 0.07–7.71 years) for those with malignant progression (P = 0.01).9

[1] Jääskeläinen J. Seemingly complete removal of histologically benign intracranial meningioma: late recurrence rate and factors predicting recurrence in 657 patients. A multivariate analysis. Surg Neurol. 1986;26:461-469.

[2] Al-Mefty O., Kadri P.A., Pravdenkova S., et al. Malignant progression in meningioma: documentation of a series and analysis of cytogenetic findings. J Neurosurg. 2004;101:210-218.

[3] Goyal L.K., Suh J.H., Mohan D.S., et al. Local control and overall survival in atypical meningioma: a retrospective study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2000;46:57-61.

[4] Jääskeläinen J., Haltia M., Servo A. Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: radiology, surgery, radiotherapy and outcome. Surg Neurol. 1986;25:233-242.

[5] Jellinger K., Slowik F. Histological subtypes and prognostic problems in meningiomas. J Neurol. 1975;208:279-298.

[6] McLean C.A., Jolley D., Cukier E., et al. Atypical and malignant meningiomas: importance of micronecrosis as a prognostic indicator. Histopathology. 1993;23:349-353.

[7] Modha A., Gutin P.H. Diagnosis and treatment of atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: a review. Neurosurgery. 2005;57:538-550.

[8] Perry A., Stafford S.L., Scheithauer B.W., et al. The prognostic significance of MIB-1, p53, and DNA flow cytometry in completely resected primary meningiomas. Cancer. 1998;82:2262-2269.

[9] Krayenbühl N., Pravdenkova S., Al-Mefty O. De novo vs. transformed atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: comparisons of clinical course, cytogenetics, cytokinetics, and outcome. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:495-504.

[10] Palma L., Celli P., Franco C., et al. Long-term prognosis for atypical and malignant meningiomas: a study of 71 surgical cases. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:793-800.

[11] Huffmann B.C., Reinacher P.C., Gilsbach J.M. Gamma knife surgery for atypical meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(Suppl):283-286.

[12] Hug E.B., Devries A., Munzenride J.E., et al. Management of atypical and malignant meningiomas: role of high-dose, 3D-conformal radiation therapy. J Neurooncol. 2000;48:151-160.

[13] Mahmood A., Caccamo D.V., Tomecek F.J., Malik G.M. Atypical and malignant meningiomas: clinicopathological review. Neurosurgery. 1993;33:955-963.

[14] World Health Organization. World Health Organization Classification of Tumors of the Central Nervous System. Lyon: IARC Press, 2007.

[15] Kaba S.E., DeMonte F., Bruner J.M., et al. The treatment of recurrent unresectable and malignant meningiomas with interferon alpha-2B. Neurosurgery. 1997;40:271-275.

[16] Katz T.S., Amdur R.J., Yachnis A.T., et al. Pushing the limits of radiotherapy for atypical and malignant meningioma. Am J Clin Oncol. 2005;28:70-74.

[17] Maier H., Ofner D., Hittmair A., et al. Classic, atypical and anaplastic meningioma: three histopathological subtypes of clinical relevance. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:616-623.

[18] Ware M.L., Larson D.A., Sneed P.K., et al. Surgical resection and permanent brachytherapy for recurrent atypical and malignant meningioma. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:55-63.

[19] Alvarez F., Roda J.M., Perez Romero M., et al. Malignant and atypical meningiomas: a reappraisal of clinical, histological and computed tomographic features. Neurosurgery. 1987;20:688-694.

[20] Chamberlin M.C. Adjuvant combined modality therapy for malignant meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 1996;84:733-736.

[21] Inoue H., Tamura M., Koizumi H., et al. Clinical pathology of malignant meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1984;73:179-191.

[22] Ojemann S.G., Sneed P.K., Larson D.A., et al. Radiosurgery for malignant meningioma: results in 22 patients. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(Suppl. 3):62-67.

[23] Prayson R.A. Malignant meningioma. A clinicopathologic study of 23 patients including MIB1 and p53 immunohistochemistry. Am J Clin Pathol. 1996;105:719-726.

[24] Rohringer M., Sutherland G.R., Louw D.F., Sima A.A. Incidence and clinicopathological features of meningioma. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:665-672.

[25] Schrell U.M., Rittig M.G., Anders M., et al. Hydroxyurea for treatment of unresectable and recurrent meningiomas: Part II—Decrease in the size of meningiomas in patients treated with hydroxyurea. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:840-844.

[26] Thomas H.G., Dolman C.L., Berry K. Malignant meningioma: clinical and pathological features. J Neurosurg. 1981;55:929-934.

[27] Sade B., Chahlavi A., Krishnaney A., et al. World Health Organization grades II and III meningiomas are rare in the cranial base and spine. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:1194-1198.

[28] Akbay A., Altundag M.K., Ozisik Y., et al. Reverse seeding of recurrent intraspinal malignant meningioma. Oncology. 2002;62:386-388.

[29] Pinsker M.O., Buhl R., Hugo H.H., Mehdorn H.M. Metastatic meningioma WHO grade II of the cervical spine: case report and review of the literature. Zentralbl Neurochir. 2005;66:35-38.

[30] Milosevic M.F., Frost P.J., Laperriere N.J., et al. Radiotherapy for atypical or malignant intracranial meningioma. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1996;34:817-822.

[31] Pasquier D., Bijmolt S., Veninga T., et al. Atypical and malignant meningioma: Outcome and prognostic factors in 119 irradiated patients. A multicenter, retrospective study of the rare cancer network. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;71:1388-1393. [Epub ahead of print]

[32] Al-Mefty O., Topsakal C., Pravdenkova S., et al. Radiation-induced meningiomas: clinical, pathological, cytokinetic and cytogenetic characteristics. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:1002-1013.

[33] Mack E.E., Wilson C.B. Meningiomas induced by high-dose cranial irradiation. J Neurosurg. 1993;79:28-31.

[34] Musa B.S., Pple I.K., Cummins B.H. Intracranial meningiomas following irradiation – a growing problem? Br J Neurosurg. 1995;9:629-637.

[35] Yang S.Y., Park C.K., Park S.H., et al. Atypical and anaplastic meningiomas: prognostic implication of clinicopathological features. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2008;79:574-580.

[36] Perry A., Stafford S.L., Scheithauer B.W., et al. Meningioma grading: an analysis of histologic parameters. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1455-1465.

[37] Foulds L. Tumor progression. Cancer Res. 1957;17:355-356.

[38] Nowell P.C. The clonal evolution of tumor cell populations. Science. 1976;194:23-28.

[39] Nowell P.C. Mechanisms of tumor progression. Cancer Res. 1986;46:2203-2207.

[40] Kleihues P., Ohgaki H. Primary and secondary glioblastomas: from concept to clinical diagnosis. Neurooncol. 1999;1:44-51.

[41] Lamszus K., Vahldiek F., Mautner V.F., et al. Allelic losses in neurofibromatosis 2–associated meningiomas. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2000;59:504-512.

[42] Perry A., Gutmann D.H., Reifenberger G. Molecular pathogenesis of meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2004;70:183-202.

[43] Pravdenkova S., Al-Mefty O., Sawyer J., Husain M. Progesterone and estrogen receptors: opposing prognostic indicators in meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2006;105:163-173.

[44] Simon M., Kokkino A.J., Warnick R.E., et al. Role of genomic instability in meningioma progression. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1996;16:265-269.

[45] Weber R.G., Mostrom J., Wolter M., et al. Analysis of genomic alterations in benign, atypical, and anaplastic meningiomas: toward a genetic model of meningioma progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14719-14724.

[46] Gursan N., Gundogdu C., Albayrak A., Kabalar M.E. Immunohistochemical detection of progesterone receptors and the correlation with Ki-67 labeling indices in paraffin-embedded sections of meningiomas. Int J Neurosci. 2002;112:463-470.

[47] Nagashima G., Aoyagi M., Wakimoto H., et al. Immunohistochemical detection of progesterone receptors and the correlation with Ki-67 labeling indices in paraffin-embedded sections of meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1995;37:478-483.

[48] Roser F., Nakamura M., Bellinzona M., et al. The prognostic value of progesterone receptor status in meningiomas. J Clin Pathol. 2004;57:1033-1037.

[49] Fewings P.E., Battersby R.D.E., Timperley W.R. Long-term follow-up of progesterone receptor status in benign meningioma: a prognostic indicator of recurrence? J Neurosurg. 2000;92:401-405.

[50] Bruna J., Brell M., Ferrer I., et al. Ki-67 proliferative index predicts clinical outcome in patients with atypical or anaplastic meningioma. Neuropathology. 2007;27:114-120.

[51] Karamitopoulou E., Perentes E., Tolnay M., Probst A. Prognostic significance of MIB-1, p53, and bcl-2 immunoreactivity in meningiomas. Hum Pathol. 1998;29:140-145.

[52] Hsu D.W., Efird J.T., Hedley-Whyte E.T. Progesterone and estrogen receptors in meningiomas: prognostic considerations. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:113-120.

[53] Dezamis E., Sanson M. The molecular genetics of meningiomas and genotypic/phenotypic correlations. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2003;159:727-738.

[54] Zang K.D. Meningioma: a cytogenetic model of a complex benign human tumor, including data on 394 karyotyped cases. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 2001;93:207-220.

[55] Lamszus K., Kluwe L., Matschke J., et al. Allelic losses at 1p, 9q, 10q, 14q, and 22q in the progression of aggressive meningiomas and undifferentiated meningeal sarcomas. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1999;110:103-110.

[56] Leone P.E., Bello M.J., de Campos J.M., et al. NF2 gene mutations and allelic status of 1p, 14q and 22q in sporadic meningiomas. Oncogene. 1999;18:2231-2239.

[57] Menon A.G., Rutter J.L., von Sattel J.P., et al. Frequent loss of chromosome 14 in atypical and malignant meningioma: identification of a putative “tumor progression” locus. Oncogene. 1997;14:611-616.

[58] Sawyer J.R., Husain M., Pravdenkova S., et al. A role for telomeric and centromeric instability in the progression of chromosome aberrations in meningioma patients. Cancer. 2000;88:440-453.

[59] Sayagues J.M., Tabernero M.D., Maill A., et al. Incidence of numerical chromosome aberrations in meningioma tumors as revealed by fluorescence in situ hybridization using 10 chromosome-specific probes. Cytometry. 2002;50:153-159.

[60] Simon M., von Deimling A., Larson J.J., et al. Allelic losses on chromosomes 14, 10, and 1 in atypical and malignant meningiomas: a genetic model of meningioma progression. Cancer Res. 1995;55:4696-4701.

[61] Bello M.J., de Campos J.M., Kusak M.E., et al. Allelic loss at 1p is associated with tumor progression of meningiomas. Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 1994;9:296-298.

[62] Cai D.X., Banerjee R., Scheithauer B.W., et al. Chromosome 1p and 14q FISH analysis in clinicopathologic subsets of meningioma: diagnostic and prognostic implications. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:628-636.

[63] Ketter R., Henn W., Niedermayer I., et al. Predictive value of progression-associated chromosomal aberrations for the prognosis of meningiomas: a retrospective study of 198 cases. J Neurosurg. 2001;95:601-607.

[64] Lee J.Y., Finkelstein S., Hamilton R.L., et al. Loss of heterozygosity analysis of benign, atypical, and anaplastic meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 2004;55:1163-1173.

[65] Leuraud P., Dezamis E., Aguirre-Cruz L., et al. Prognostic value of allelic losses and telomerase activity in meningiomas. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:303-309.

[66] Lopez-Gines C., Cerda-Nicolas M., Barcia-Salorio J.L., Llombart-Bosch A. Cytogenetical findings of recurrent meningiomas: a study of 10 tumors. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1995;85:113-117.

[67] Lopez-Gines C., Cerda-Nicolas M., Gil-Benso R., et al. Association of loss of 1p and alterations of chromosome 14 in meningioma progression. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2004;148:123-128.

[68] Maillo A., Orfao S., Sayagues J.M., et al. New classification scheme for the prognostic stratification of meningioma on the basis of chromosome 14 abnormalities, patient age, and tumor histopathology. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3285-3295.

[69] Muller P., Henn W., Niedermayer I., et al. Deletion of chromosome 1p and loss of expression of alkaline phosphatase indicate progression of meningiomas. Clin Cancer Res. 1999;5:3569-3577.

[70] Pfisterer W.K., Hank N.C., Preul M.C., et al. Diagnostic and prognostic significance of genetic regional heterogeneity in meningiomas. J Neurooncol. 2004;6:290-299.

[71] Surace E.I., Lusis E., Murakami Y., et al. Loss of tumor suppressor in lung cancer-1 (TSLC1) expression in meningioma correlates with increased malignancy grade and reduced patient survival. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2004;63:1015-1027.

[72] Nagashima G., Aoyagi M., Yamamoto M., et al. P53 overexpression and proliferative potential in malignant meningiomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1999;141(1):53-61.

[73] Matsuno A., Fujimaki T., Sasaki T., et al. Clinical and histopathological analysis of proliferative potentials of recurrent and non-recurrent meningiomas. Acta Neuropathol. 1996;91:504-510.

[74] Amatya V.J., Takeshima Y., Sugiyama K., et al. Immunohistochemical study of Ki-67 (MIB-1), p53 protein, p21WAF1, and p27KIP1 expression in benign, atypical, and anaplastic meningiomas. Hum Pathol. 2001;32:970-975.

[75] Cho H., Ha S.Y., Park S.H., et al. Role of p53 gene mutation in tumor aggressiveness of intracranial meningiomas. J Korean Med Sci. 1999;14:199-205.

[76] Wrobel G., Roerig P., Kokocinski F., et al. Microarray-based gene expression profiling of benign, atypical and anaplastic meningiomas identifies novel genes associated with meningioma progression. Int J Cancer. 2005;20(114):249-256.

[77] Younis G.A., Sawaya R., DeMonte F., et al. Aggressive meningeal tumors: review of a series. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:17-27.

[78] Verheggen R., Finkenstaedt M., Bockermann V., Markakis E. Atypical and malignant meningiomas: evaluation of different radiological criteria based on CT and MRI. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien). 1996;65:66-69.

[79] Zhang H., Rödiger L.A., Shen T., et al. Perfusion MR imaging for differentiation of benign and malignant meningiomas. Neuroradiology. 2008;50:835-840.

[80] Filippi C.G., Edgar M.A., Uluğ A.M., et al. Appearance of meningiomas on diffusion-weighted images: correlating diffusion constants with histopathologic findings. Am J Neuroradiol. 2001;22:65-72.

[81] Hakyemez B., Yildirim N., Gokalp G., et al. The contribution of diffusion-weighted MR imaging to distinguishing typical from atypical meningiomas. Neuroradiology. 2006;48:513-520.

[82] Cho Y.D., Choi G.H., Lee S.P., Kim J.K. (1)H-MRS metabolic patterns for distinguishing between meningiomas and other brain tumors. Magn Reson Imaging. 2003;21:663-762.

[83] Buhl R., Nabavi A., Wolff S., et al. MR spectroscopy in patients with intracranial meningiomas. Neurol Res. 2007;29:43-46.

[84] Shino A., Nakasu S., Matsuda M., et al. Noninvasive evaluation of the malignant potential of intracranial meningiomas performed using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:928-934.

[85] Adegbite A.B., Khan M.I., Paine K.W., Tan L.K. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurosurg. 1983;58:51-56.

[86] Kallio M., Sankila R., Hakulinen T., Jääskeläinen J. Factors affecting operative and excess long-term mortality in 935 patients with intracranial meningioma. Neurosurgery. 1992;31:2-12.

[87] Sankila R., Kallio M., Jääskeläinen J., Hakulinen T. Long-term survival of 1986 patients with intracranial meningioma diagnosed from 1953 to 1984 in Finland. Cancer. 1992;70:1568-1576.

[88] Simpson D. The recurrence of intracranial meningiomas after surgical treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1957;20:22-39.

[89] Rogers L., Mehta M. Role of radiation therapy in treating meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23:E4.

[90] Dziuk T.W., Woo S., Butler E.B., et al. Malignant meningioma: an indication for initial aggressive surgery and adjuvant radiotherapy. J Neurooncol. 1998;37:177-188.

[91] Condra K., Buatti J., Mendenhall W., et al. Benign meningiomas primary treatment selection affects survival. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1997;39:427-436.

[92] Stafford S.L., Pollock B.E., Foote R.L., et al. Meningioma radiosurgery: tumor control, outcomes, and complications among 190 consecutive patients. Neurosurgery. 2001;49:1029-1038.

[93] Hakim R., Alexander E., Loeffler J.S., et al. Results of linear accelerator based radiosurgery for intracranial meningiomas. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:446-454.

[94] Harris A.E., Lee J.Y.K., Omalu B., et al. The effect of radiosurgery during management of aggressive meningiomas. Surg Neurol. 2003;60:298-305.

[95] Ware M.L., Larson D.A., Sneed P.K., et al. Surgical resection and permanent brachytherapy for recurrent atypical and malignant meningioma. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:55-63.

[96] Noël G., Bollet M.A., Calugaru V., et al. Functional outcome of patients with benign meningioma treated by 3D conformal irradiation with a combination of photons and protons. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;62:1412-1422.

[97] Newton H.B. Hydroxyurea chemotherapy the treatment of meningiomas. Neurosurg Focus. 2007;23:E11.

[98] Grunberg S.M., Rankin C., Townsend J., et al. Phase III double-blind randomized placebo controlled study of mifepristone (RU) for the treatment of unresectable meningioma. ASCO Proceedings. 56a:20, 2001.

[99] Perry A., Scheithauer B.W., Stafford S.L., et al. Malignancy” in meningiomas: a clinicopathologic study of 116 patients, with grading implications. Cancer. 1999;85:2046-2056.