Chapter 6 Management of Alopecia

Summary

Introduction

With current techniques, hair transplants can look totally natural and without signs that a procedure has been performed.1 Hair transplantation has, however, a poor reputation because so many patients in the past have had less than acceptable results.2 Scalp reconstruction with flaps and excisions and the use of tissue expanders for male patients with genetic hair loss are now rarely used except in the management of difficult secondary cases.3–20

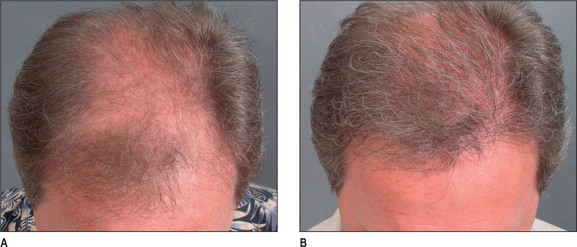

Improvements in results in the past 15 years are due to the work of many in the field, and in particular, Dr Carlos Uebel from Brazil,21,22 who was one of the first to popularize the use of small natural-appearing grafts in large numbers performed at a single session. Today, rather than transferring a few hundred grafts at each session requiring numerous procedures, it is not unusual to transfer 1500, 2000, and even 3000 grafts in a single session.

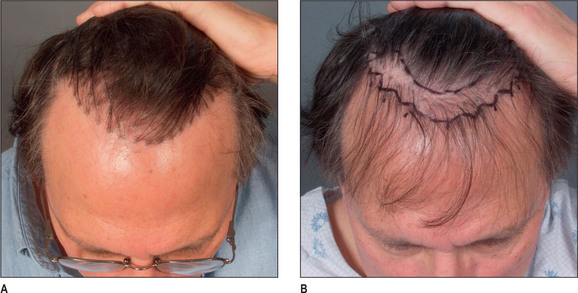

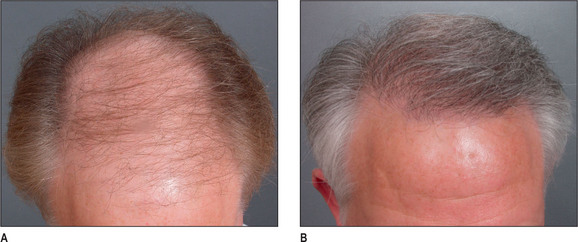

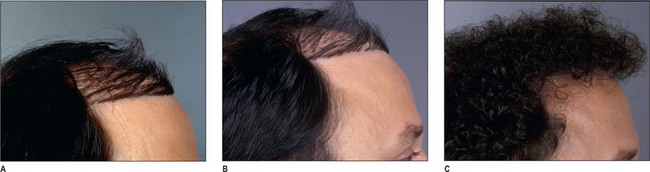

Importance of Type of Graft and Design of a Natural Hairline

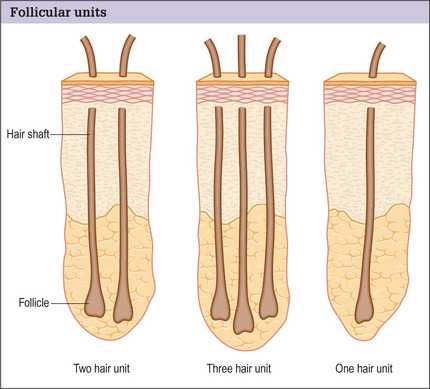

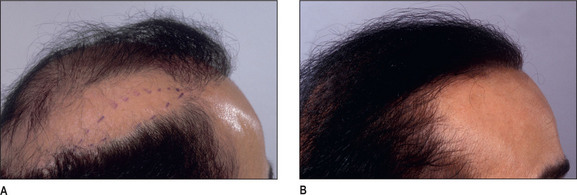

A discussion of transplantation usually refers to micro or mini grafts.23 Current nomenclature uses the term follicular grafts,24–26 which are clusters of one to three hairs that emerge from the scalp as a unit. Grafts often used to contain 10, 20, and even 40 hairs per each graft, so creating an unnatural appearance (Fig. 6.1A&B), and the hairline was often poorly designed. A successful and aesthetically pleasing hair restoration is as demanding as any other aesthetic facial procedure.

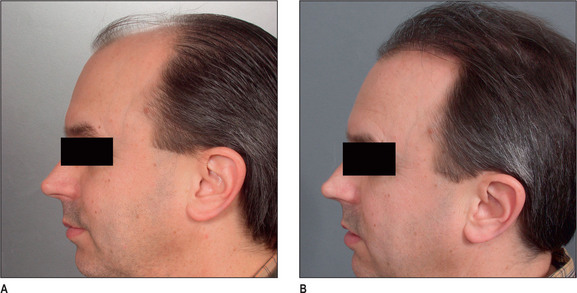

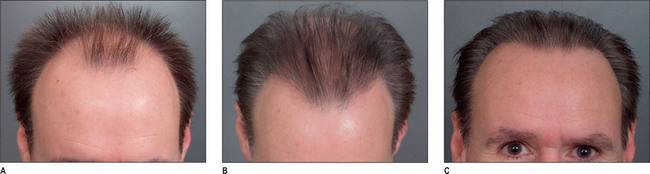

The frontotemporal recession is an important component of creating a mature natural hairline in males.27 This anatomic landmark is formed by the junction of two lines, consisting of the frontal and temporal hairlines, which converge in an acute angle. It is critical in creating a natural-appearing male hair transplant to maintain this normal frontotemporal recession. In hair restorations where the frontotemporal angle is not created, the patient frequently has an un-natural result, creating either a feminine or immature male hairline.

Other important components of a natural hairline include the transition anteriorly from fine to thicker hair with increasing density, and a significant degree of irregularity along the hairline margin. Normal hairlines should not appear straight and regular. Perfectly straight hairlines are characteristic of unnatural-appearing hair transplants. Unsatisfactory results with hair transplants usually demonstrate a fundamental lack of knowledge of these critical points required to create a natural-appearing hairline.28

Indications

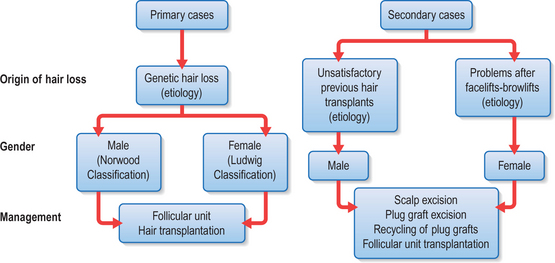

Most patients seeking hair restoration due to genetic hair loss are male. Approximately 15% of patients who have primary alopecia in my current practice are women and demonstrate typical genetic pattern hair loss. The other main group of patients have had previous hair transplantation with poor results;29–31 these patients are more difficult to treat and fall into two groups:

Most women with hair loss may not be good candidates for hair transplants and may suffer from metabolic autoimmune disorders

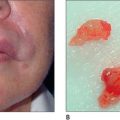

One of the main indications in women is secondary or traumatic alopecia after procedures such as facelifts or forehead lifts. In these patients hair loss results from excessive tension or undermining of the hair follicle.32 Such women are ideal for hair transplantation because scars or abnormally high hairlines can be readily corrected. The most common area needing hair transplantation is probably the temporal and preauricular area.

Male Androgenic Alopecia

In most men, hair loss is related to androgenic alopecia. This form of alopecia is a response to androgens, which reduce the rate of hair growth as well as the diameter of the hair shaft.33 Also, the growth phase of hair referred to as anagen is shortened. It is believed that testosterone is converted by the enzyme 5-alpha reductase to dihydrotestosterone (DHT),34 which targets the hair and causes genetic hair loss. In most men with hair loss, the hair follicles in the frontal and crown regions appear to be most susceptible to DHT, leading to androgenic alopecia. In most patients, 30–50% of the hair has been lost before it becomes apparent. As the average normal head has 100 000–150 000 hairs, a significant amount of hair loss is necessary before it becomes apparent.

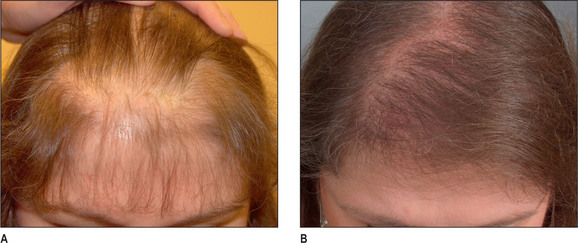

Female Hair Loss

Female hair loss is frequently more diffuse, and many women are not good candidates for hair restoration because of a lack of good donor hair.35 However, a subgroup of women present with hair loss similar to androgenic alopecia36 and usually have good hair density in the lateral and posterior areas of the scalp. Many of these women have a history compatible with that seen in male pattern hair loss and report many family members with either thin hair or balding scalps.

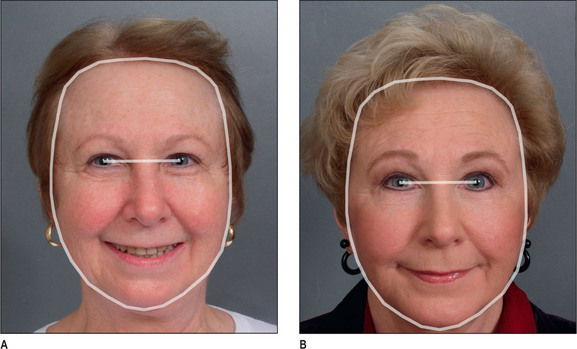

Unlike male pattern hair loss of the genetic form, women with genetic hair loss tend to maintain a low frontal hairline with an anterior margin of hair (Fig. 6.2A&B). This is very different from men where there is progressive elevation of the frontal hairline and increasing temporal recession over time. Women, however, frequently maintain a frontal hairline for life, and this factor requires hair transplantation to be performed, beginning from the frontal hairline and continuing posteriorly to fill in the defect.

Patient Selection

As in all areas of aesthetic surgery, realistic expectations of what can be accomplished with hair restoration are important.

Preoperative History and Considerations

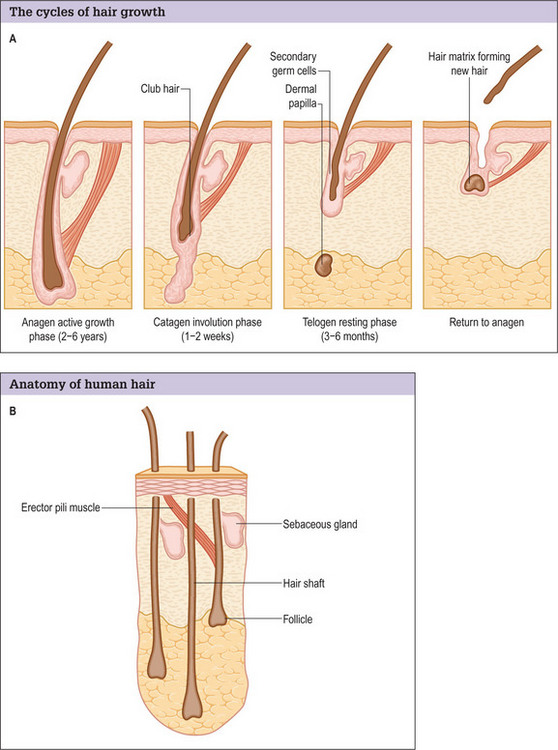

Hair normally passes through three cycles (Fig. 6.3A&B).37

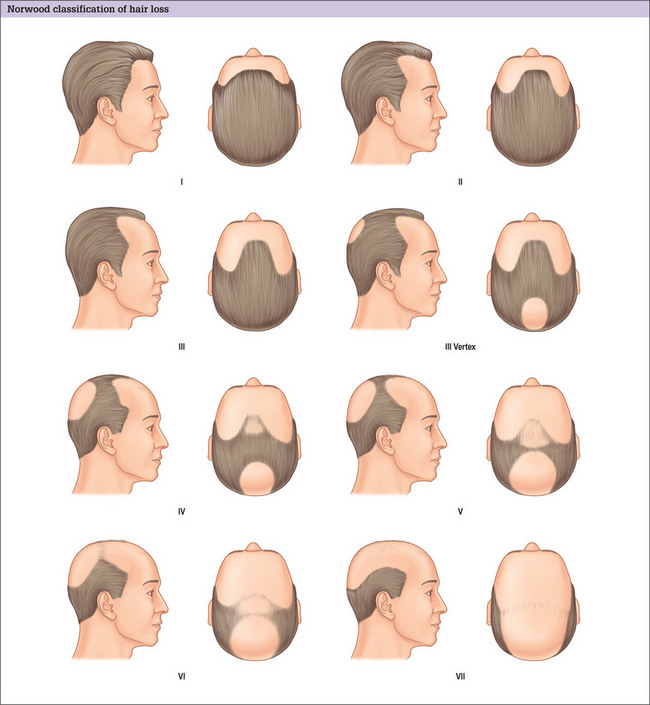

Classification of Alopecia

The major classification of alopecia used by most physicians today is the Norwood classification, which is a modification of Hamilton’s original description (Fig. 6.4).38 There are many other classifications, but most divide baldness into six to seven primary groups, with sub-groups included.39,40 These classifications can be useful, but most patients do not fit into a single specific classification or hair loss type exactly.

Ludwig has described a system for classifying androgenic alopecia in women.41

Hair Type

Goals of Transplantation

Hairline

It is important that the patient understands that the goal is to create a hairline that is harmonious with their facial characteristics and to create balance. One term that is frequently used is facial framing (Fig. 6.6A&B). This creates a more balanced appearance in the anatomic components of the face. Typically, the face can be divided into equal thirds, but in a patient who has a receding hairline, the eyes appear to have a more centralized appearance; creating a lower hairline produces better balance by framing the facial characteristics.

During the consultation, it is useful to draw the proposed transplantation pattern on the patient’s scalp and to allow the patient to see it (i.e. the most appropriate hairline) in a mirror. Patients given a marking pen will frequently draw the hairline in a relatively low position, which is usually not appropriate because a relatively youthful hairline now may lead to problems and dissatisfaction later. A demonstration of the Norwood classification allows patients to understand the normal nature of androgenic alopecia as hair recedes. A natural hairline will age appropriately with the patient as temporal recession and elevation in the frontal hairline progresses. For most patients the frontal hairline should be at least 8–10 cm above the glabella (Fig. 6.7A&B).

Special Cases

Operative Approach

Surgical Anatomy

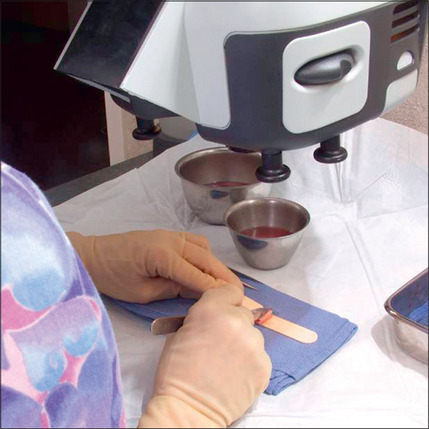

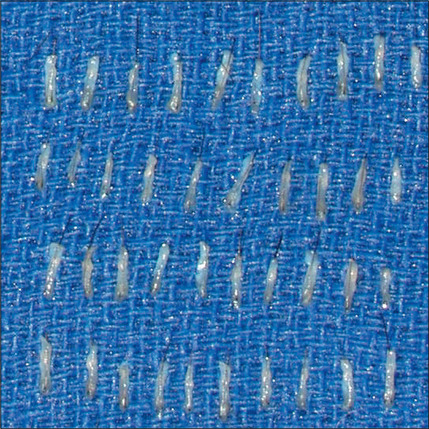

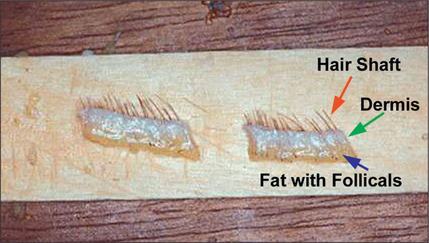

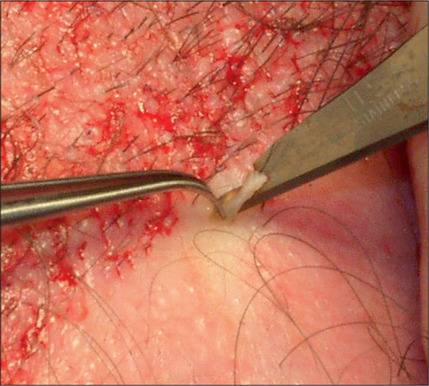

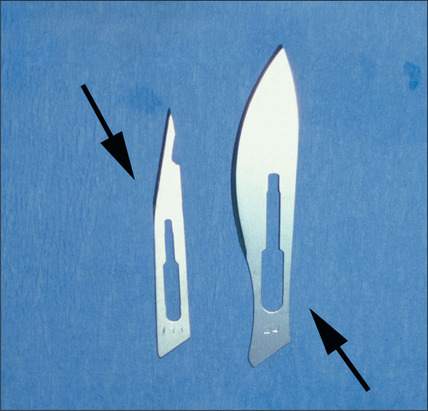

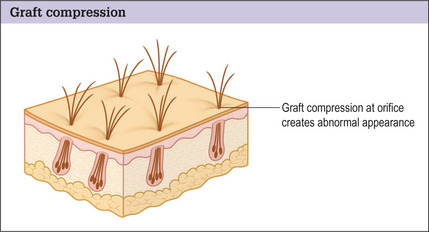

Hair is now known to grow in follicular units in which there is a clustering of 1–4 hairs (Fig. 6.9). The number of hairs varies greatly, based on the patient’s hair type and hair characteristics. To create a natural result, it is critical to use these follicular units to avoid unnatural bunching of hair, and to use magnification during the dissection and preparation of these grafts to create appropriate follicular units (Figs 6.10 and 6.11). A team approach is therefore required with skilled individuals who cut the grafts and assist in their placement during procedures that often entail 2000–3000 grafts per session.

Surgical Technique

Although the equipment and instrumentation for hair transplant is relatively simple, the technique itself can be relatively complex, especially when large numbers of grafts are being transplanted at one time. The technique described here has been developed by Carlos Uebel of Brazil and has significantly simplified the performance of large transplantation sessions using small, natural-appearing grafts.

Box 6.1 Logistics of hair transplantation

Creating an appropriate environment

Anesthesia

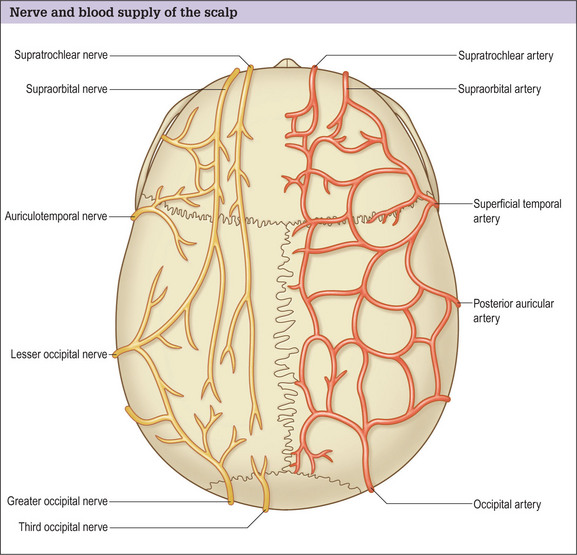

Hair transplantation can be carried out in the office with local anesthesia and acquiring good anesthesia is relatively simple. Knowledge of the anatomy of the nerves in the scalp allows a satisfactory level of local anesthesia in both the donor and the recipient areas (Fig. 6.25).

Anesthesia is achieved with a dilute epinephrine solution, initially blocking the occipital nerves posteriorly in the donor site (Fig. 6.26). This is followed by tumescence of a very dilute solution in the area to distend the posterior scalp off the galea.

In the recipient area anteriorly, anesthesia is accomplished with both a ring block and occasionally, supraorbital nerve blocks, which facilitate the injection of the ring block.

Scalp Excisions

In the past, however, scalp excisions were often performed in conjunction with hair transplantation42–45 to reduce the total surface that required transplantation. The most frequent technique was midline excision of non-hairbearing scalp with advancement of the lateral hairbearing scalp flaps toward the midline. Usually this only partially reduces the area requiring transplantation and creates several problems. Advancing lateral flaps superiorly creates an abnormal hair pattern with divergence of the hair away from midline, resulting in a midline scar, which creates a slot deformity; even with aggressive mobilization there is significant stretch back, leading to a wide scar, with hair diverging away from the scar.46 The final result was often far less than optimal. Attempts have been made to reduce the amount of stretch back or scar widening using various techniques47,48 by reducing the tension of the incision closure with unique sutures and elastic membranes internally.

Scalp excisions for secondary alopecia

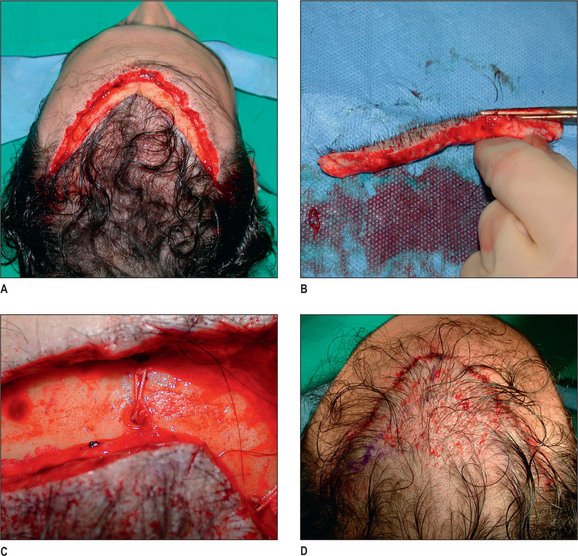

Scalp excisions are particularly useful in secondary cases. Patients who have had large plug grafts placed too low on the forehead or temporal region cannot usually be treated with just further hair grafting. Patients who have had plug grafts can be treated with:

In selected patients, the best option is complete excision of the unsightly anterior plugs with superior advancement of the forehead followed by regrafting (Fig. 6.27A-D). At the time of the excision, the large plug grafts are recut into micrografts and reinserted at the same time.

Tissue Expansion in Alopecia Management

Tissue expansion is no longer considered to be a primary modality for the treatment of male pattern baldness, and is mainly used for reconstructed scalp surgery. Although several authors have developed specific expanders for hair restoration and specific flaps to be used in conjunction with the expansion process (Fig. 6.29A&B), none of these techniques are in mainstream use.

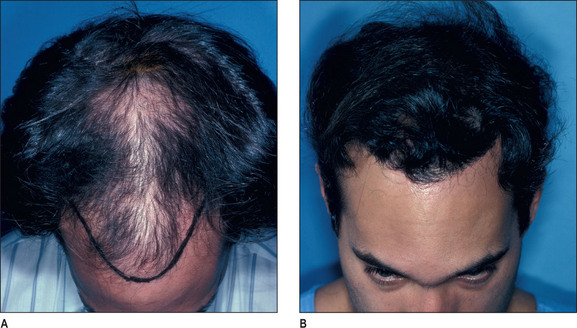

Primary Hair Transplantation: Case Study 1 (Figs 6.30 and 6.31A-C)

Operative Approach

Primary Hair Transplantation: Case Study 2 (Fig. 6.31A-D)

Preoperative considerations

Operative Approach

Discussion

Secondary Hair Transplantation: Case Study 3 (Fig. 6.32A-C)

Preoperative considerations

This patient had to wear a hairpiece to cover his scalp.

Is there adequate donor hair?

Operative Approach

Operative Approach

With proper attention to the angle of the grafts, the appearance can be dramatically improved.

Complications and Side Effects

Hair transplantation has a low incidence of complications when properly performed.

Postoperative Care

Immediate Postoperative Period

Once the grafts have been inserted, an appropriate dressing is often applied and then removed after 24 hours. Most patients can wash their hair within 24 hours: carefully at the recipient site, and normally at the donor site. For the first 6 days after the transplant the patient is instructed to blot soap on to the recipient site and rinse it with a cup. After 6 days, a normal stream from the shower can hit directly onto the recipient site. It is important for the patient to progressively increase their aggressiveness in washing.

1. Orentreich N. Autografts in alopecia and other selected dermatological conditions. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1959;83:463.

2. Fisher J. Revision of the unfavorable result in hair transplantation. Plast Surg. 2005:167-178.

3. Manders E.K., Graham W.D.III, Schenden M.J.L. Skin expansion to eliminate large scalp defects. Ann Plast Surg. 1984;12:305.

4. Juri J. Use of parieto-occipital flaps in the surgical treatment of baldness. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1975;55:456.

5. Juri J., Juri C., Arufe H.N. Use of rotation scalp flaps for treatment of occipital baldness. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1978;61:23.

6. Elliott R.A. Lateral flaps for instant results in male pattern baldness. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;60:699.

7. Flemming R.W., Mayer T.G. Short and long scalp flaps in the treatment of male pattern baldness. Arch Otolaryngol. 1981;107:403.

8. Ohmori K. Free scalp flap. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1980;65:42.

9. Adson M.D., Anderson R.D., Argenta L.C. Scalp expansion in the treatment of male pattern baldness. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1987;79:906.

10. Elliott R.A. Lateral flaps for instant results in male pattern baldness. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1977;60:699.

11. Mayer T.G., Fleming R.W., Patterson A.S. Aesthetic and reconstructive surgery of the scalp. St Louis: CV Mosby, 1992;39-45.

12. Manders E.K., Graham W.P.III. Alopecia reduction by scalp expansion. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1984;10:967.

13. Argenta L.C., Marks M.W., Anderson R.R.D. Treatment of male pattern baldness by tissue expansion. In: Courtiss E.H., editor. Male aesthetic surgery. 2nd edn. St. Louis: CV Mosby; 1991:212-225.

14. Anderson R.D. The expanded ‘BAT’ flap for treatment of male pattern baldness. Ann Plast Surg. 1993;31:385.

15. Anderson R.D. New expanded scalp flap techniques for elimination of male pattern baldness. In: Unger W.P., editor. Hair transplantation. 3rd edn. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1995:673.

16. Fisher J. Discussion: correction of the cornrow transplant and other common problems in surgical hair restoration. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:1528.

17. Under M.G. The Y-shaped pattern of alopecia reduction and its variations. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1984;10:980.

18. Unger M.G., Unger W.P. Midline alopecia reduction combined with hair transplantation. Head Neck Surg. 1985;7:303.

19. Alt T.H. Scalp reduction as an adjunct to hair transplantation. Review of the relevant literature and presentation of an improved technique. J Dermol Surg Oncol. 1980;6:1011.

20. Nahai F, Fisher J. Reoperation, refinement and treatment of complications after hair transplantation. The art of aesthetic surgery, principles and techniques. 47; 1766–1785.

21. Uebel C.O. Micrografts and minigrafts: a new approach to baldness surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 1991;27:476.

22. Uebel C.O. Hair replacement surgery: micrografts and flaps. New York: Springer-Verlag, 2000.

23. Nordstrom R.E.A. Micrografts’ for improvement of the frontal hairline after hair transplantation. Aesthetic Plast Reconstr Surg. 1981;5:97.

24. Bernstein R.M., Rassman W.R. Follicular transplantation, patient evaluation and surgical planning. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:771.

25. Berstein R.M., Rassman W.R. The aesthetics of follicular transplantation. Dermatol Surg. 1997;23:785.

26. Bernstein R.M., Rassman W.R. The logic of follicular unit transplantation. Dermatol Clin. 1999;17:277.

27. Fisher J. Hair restoration. In: Plastic Surgery 59:658

28. Guyuron B, Dinarso Evans & Pershing. Treatment of soft tissue. Hair transplantation. 7:883–890.

29. Vogel J.E. Correction of the cornrow hair transplantation and other common problems in surgical hair restoration. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:1528.

30. Epstein J.S. Revision of surgical hair restoration: repair of undesirable results. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999:104-222.

31. Swinehart J.M. Hair repair surgery. Corrective measures for improvement of older large-graft procedures and scalp scars. Dermatol Surg. 1999;25:523-528.

32. Berrera A. The use of micrografts and mini grafts for the correction of the postrhytidectomy lost sideburn. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:2277.

33. Schweikert H.U., Wilson J.D. Androgen metabolism in isolated human hair roots. In: Orfanos C.E., Montagna W., Stuttgen G., editors. Hair Research. New York: Springer-Verlag; 1981:210-214.

34. Kaufman K.D. 5a-Reductase inhibitors. Dermatol Ther. 1998;8:42.

35. DeVillez R.L., Jacobs J.P., Szpunar C.A., Warner M.L. Androgenetic alopecia in the female. Treatment with 2% topical minoxidil solution. Arch Dermatol. 1994:130-303.

36. Halsner U., Lucas M. New aspects in hair transplantation for females. Dermatol Surg. 1995;21:605.

37. Nigman A.M. The human hair cycles. J Invest Dermatol. 1959;33:307.

38. Norwood O.T. A classification of male pattern baldness. South Med J. 1975;68:1359.

39. Hamilton J.B. Patterned loss of hair in man: types and incidence. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1951;53:708.

40. Bouhanna P., Dardour J.C. Hair Replacement Surgery. New York: Springer-Verlag, 1996.

41. Ludwig E. Classification of the types of androgenic alopecia (common baldness) arising in the female sex. Br J Dermatol. 1977;97:319.

42. Unger M.G. The Y-shaped pattern of alopecia reduction and its variations. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1984;10:980.

43. Unger M.G., Unger W.P. Midline alopecia reduction combined with hair transplantation. Head Neck Surg. 1985;7:303.

44. Alt T.H. Scalp reduction as an adjunct to hair transplantation. Review of the relevant literature and presentation of an improved technique. J Dermatol Surg Oncol. 1980;6:1011.

45. Marzola M. Combination of lateral scalp reductions and preauricular flaps and hair replacement without punch grafts. In: Unger W., Nordstrom R., editors. Hair Transplantation. 2nd edn. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1988:691-705.

46. Nordstrom R.E. Stretch-back in scalp reductions for male pattern baldness. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1984;73:422.

47. Frechet P. Scalp extension. In: Unger W.P., editor. Hair Transplantation. 3rd edn. New York: Marcel Dekker; 1995:625-657.

48. Nordstrom R.E.A., Greco M., Raposio E. The ‘Nordstrom suture’ to enhance scalp reductions. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;107:577.