Problem 27 Management of acute coronary syndrome

The patient has never been diagnosed with, or been investigated for, coronary artery disease.

Current medication is perindopril 10 mg daily for hypertension.

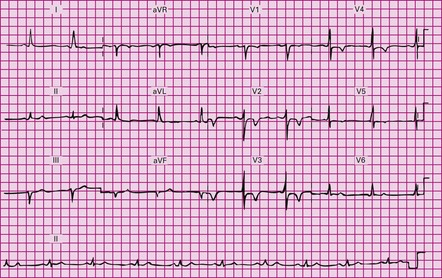

You interpret the ECG (Figure 27.1), and your consultant asks you your opinion.

Q.8

Could the patient be having a non-ST elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)?

You have made your diagnosis, now you need to decide what to do about it.

Thirty minutes later the troponin-I comes back at 1.8 µg/L (normal range <0.04 µg/L).

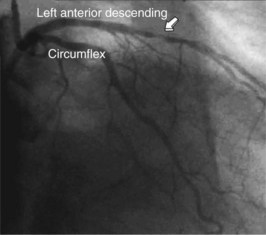

The day after presentation the patient is taken to the cardiac catheterization laboratory where a coronary angiogram is performed (Figure 27.2). It shows a severe stenosis of the left anterior descending coronary artery and this is treated with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) with the use of a bare metal stent. A left ventriculogram is also performed and shows normal left ventricular systolic function. No heparin is required after a PCI, so the heparin infusion is stopped.

Answers

Whether inspiration or changes in posture change the severity of the pain.

A.4 An acute coronary syndrome (ACS).

A.6 Sinus rhythm, normal axis and anterior T wave inversion.

A.10 The biomarker elevation enables us to now diagnose a NSTEMI – i.e. a myocardial infarction.

A.14 Discharge medications include the following combination:

Revision Points

, http://circ.ahajournals.org/cgi/reprint/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185752. ACC/AHA NSTEACS guidelines

, http://www.escardio.org/guidelines-surveys/esc-guidelines/GuidelinesDocuments/guidelines-NSTE-ACS-FT.pdf. European Society of Cardiology NSTEACS guidelines

, http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/full/360/21/2237. Very short review of NSTEACS management