Problem 51 Management of a young man who is HIV positive

The partner is also found to be HIV antibody positive and has similar hepatitis serology. The partner describes a painless lesion on the tip of his penis which has been present for 10 days (Figure 51.1).

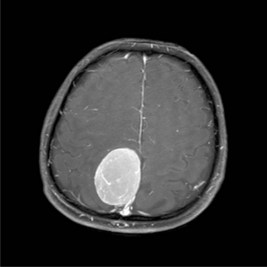

On examination he appears thinner than previously and looks depressed. He is afebrile. His oral mucosa is coated with numerous thick white plaques (Figure 51.2). He has generalized lymphadenopathy, the nodes being 1–2 cm in size. You refer him to a hospital infectious diseases clinic. His blood screens reveal his haemoglobin has dropped to 112 g/L but his complete blood count is otherwise normal, his CD4+ lymphocyte count has dropped to 210 cells/µL and the HIV viral load is >200 000 copies/µL.

Answers

A.5 The classic cause of a painless genital ulcer is the chancre of primary syphilis. Figure 51.1 shows an erythematous painless ulcer on the edge of the glans (the foreskin is retracted in the photograph). Where the foreskin rests on the primary ulcer, a secondary ulcer has occurred, termed a ‘kiss-lesion’. This is a classic appearance of primary syphilis. This ulcer is highly infectious, containing millions of spirochaetes. Even without treatment, this ulcer will heal in 10–14 days, followed later by lesions of secondary syphilis. For many years syphilis has been extremely rare; however, since 2005 there have been increasing numbers of cases of primary syphilis among men who have sex with men. Other possible diagnoses include herpes simplex ulcers (usually painful) or cancer (the history is too short). Diagnosis of primary syphilis requires demonstrating the spirochaetes in the lesion with dark field microscopy or polymerase chain reaction for treponemal DNA. Treatment is one single dose of 1.8 g IM benzathine penicillin. The partner must also receive treatment, even if his serology is negative.

In many countries, diagnosis of HIV infection requires notification of public health authorities.

A.7 Figure 51.2 illustrates white plaques of oral candida infection on the hard palate. The patient’s CD4+ count is 210 cells/µL indicating advanced immunodeficiency; he has developed accompanying constitutional symptoms, lymphadenopathy and an opportunistic infection (oral candidiasis). He has symptomatic HIV infection with uncontrolled HIV replication as demonstrated by his high viral load. He should be managed in conjunction with a clinic specializing in HIV medicine.

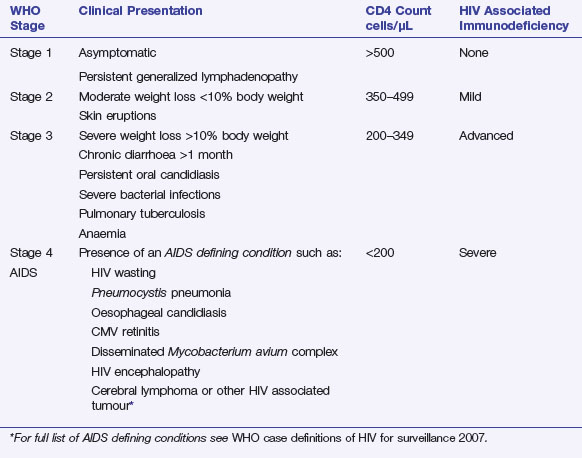

Principles of HIV Management

The World Health Organization divides HIV infection into four stages for clinical and surveillance purposes (Table 51.1). This patient has CD4+ count of 210 cells/µL, weight loss and persistent oral candidiasis. He has stage 3 disease with advanced HIV-associated immunodeficiency. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) is said to be present when a patient has stage 4 immunodeficiency and an ‘AIDS defining condition’ has been diagnosed. This patient does not have AIDS, but he does have advanced immunodeficiency (stage 3) due to his HIV infection.