Pain management

INTRODUCTION AND OVERVIEW

One of the most common reasons for people presenting to a healthcare practitioner is the presence of pain. Many people in our community also experience persistent pain, with most studies showing that around 20% of the population suffer from some type of chronic pain problem.1 In the past 25 years, there have been some major shifts in our thinking regarding the treatment of pain. One is an increased understanding of the biological changes that occur in the presence of pain. These include neuroplastic changes within the central nervous system that need to be addressed as part of successful pain management. The other has been the increasing prominence of a holistic approach to assessment and treatment. This has come from two directions. Pain practitioners have increasingly recognised the limitations of a purely biomedical approach to pain management. Many patients have also demonstrated dissatisfaction with this type of approach. The large number of people using complementary and alternative treatments as part of their pain management indicates the limitations of currently available treatments as well as a desire for a more holistic approach.

BOX 38.4 Complex regional pain syndrome

TYPES OF PAIN

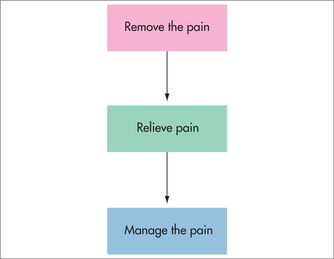

Pain is often divided clinically into acute, cancer and chronic non-cancer pain. This division reflects differences in treatment approach, although to some extent each of these aims applies to any type of pain (Fig 38.1). For acute pain, the emphasis is generally on removing the pain by identifying the cause and providing pain relief until healing occurs. In cancer pain, there is a stronger focus on pain relief, as removal of the cause of pain may be difficult. The emphasis in chronic non-cancer pain is generally on pain relief, with a stronger focus on pain management. In many chronic pain conditions, the specific cause of the pain cannot be identified with certainty, or may not be treatable. Using an acute pain approach in people with chronic non-cancer pain, with its ongoing search for a cause and removal of the pain, can be counter-productive, preventing people from accepting and dealing with their pain, and prolonging and even exacerbating their disability.

PAIN PATHOLOGY

BIOLOGICAL

Pain is a primary indicator of tissue pathology. From a biological perspective, pain can be divided into two pain types, based on underlying mechanisms (Box 38.1). Nociceptive pain is pain arising from pathology in somatic and visceral structures, such as bone fractures, appendicitis and renal calculi. Neuropathic pain is pain arising from pathology in neural structures, including the peripheral nervous system (e.g. diabetic neuropathic pain and postherpetic neuralgia) and the central nervous system (e.g. spinal cord injury pain and central post-stroke pain). Pain is initiated by damage or potential damage to somatic, visceral or neural tissues. However, a number of secondary changes including sensitisation at the periphery (peripheral sensitisation) and in the central nervous system (central sensitisation) are associated with trauma and the transmission of pain signals.2 These secondary processes further amplify the pain experience. This means that the treatment of pain often needs to address these secondary changes as well as the underlying cause or generator of the pain.

PSYCHOLOGICAL

Psychological processes are also extremely important in the experience of pain.3 Although many texts refer to psychogenic pain, pain caused by psychological factors is rare and the term may be unhelpful. On the other hand, psychological factors invariably contribute to pain and are a large determinant of the intensity and quality of the pain experience as well as the behaviours that arise as a result of nociceptive and neuropathic stimuli. Mood dysfunction is also a very common consequence of pain. Therefore psychological factors need to be considered and assessed in any person who presents with pain.

Brain imaging studies demonstrate that the perception of pain is not localised to any one brain structure or region, but involves the interaction of many regions that register and modify pain signals, including those involved with attention, mood, emotion, fear and cognition. It is therefore extremely difficult to separate the physical aspect of the pain experience from the suffering that accompanies it. ‘Pain’ can also be experienced vicariously. Empathy, or experiencing another’s pain, has been shown to produce changes in brain activity in the observer that are similar to those in the loved one who is actually experiencing the physical pain—apart from the localisation of any pain inputs.4

Concluding that mind and emotion affect the experience of pain does not imply that the pain is ‘imagined’ but that the relationship between pain perception and the extent of physical tissue damage is very variable. There is strong evidence indicating that the central nervous system is sensitised in many chronic pain states, and it is hypothesised that this sensitisation may be maintained by ‘sustained attention and arousal’.5,6 This means that a person with chronic pain can have accentuated pain in the presence of hypervigilance, preoccupation and neuronal hyperactivity, and may go some way to explaining why emotional state has such a major effect on symptomatology for people with chronic pain syndromes. These physiological and psychological changes provide a link between mind and body and a connection between mood, cognitions and the sensation of pain. From a therapeutic perspective, helping to diminish hypervigilance and reactivity to the experience of pain may explain on a clinical and neurological level the better outcomes of people with chronic pain syndromes who include psychological strategies such as stress management or mindfulness as part of their therapeutic approach. Other reasons why the relaxation response or improving emotional state and mental health may help with chronic pain include reduction in muscle tension, the anti-inflammatory effect of stress reduction, improved responsiveness to endorphins and effects on gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA).7,8

ENVIRONMENTAL INFLUENCES

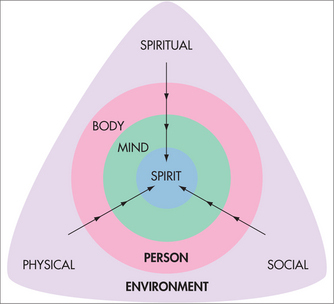

Pain does not occur in isolation but instead within a context that has a direct bearing on the experience of pain and the person’s response to pain. Environmental influences can be divided into three broad categories: physical, social and spiritual (Fig 38.2). Physical factors that arise from a person’s working or living situation and recreational activities may directly influence or cause pain. For example, for someone in a sedentary occupation with chronic pain, seating posture may have a large bearing on the presence of pain. Social factors such as relationships with family, friends, colleagues, employer or supervisor and cultural background can also strongly influence a person’s experience of pain and their pain behaviour. For example, the way a spouse or partner responds to a person’s pain is a major determinant of the way in which a person with pain will behave. Spiritual factors refer to non-physical, non-personal factors that may influence a person’s experience of pain. From a religious perspective, it is known that a person’s view of God affects their pain. For example, those who view God as punishing or cruel have worse pain outcomes than those who see God as forgiving.9 Many people without any religious affiliation also attribute improvement in their pain to an inherent, ‘supernatural’ ability of certain objects, people or a ‘higher power’. Whether these improvements are real or imagined and whether they are simply due to the physical or psychological properties of the intervention is a matter of ongoing debate and study. Nevertheless, it is difficult to consider a person’s pain from a holistic perspective without recognising and assessing the possible contribution of these factors to their pain experience.

ASSESSMENT OF PAIN

AIMS OF ASSESSMENT

One aim of pain assessment is first to identify the contribution of biological factors to pain, whether nociceptive or neuropathic. The distinction between nociceptive and neuropathic pain is made because the underlying mechanisms giving rise to pain appear to be different, with different pain characteristics and response to treatment (Table 38.1). Nociceptive pain is often dull or aching and, in the case of musculoskeletal pain, related to activity or position. Although not diagnostic, neuropathic pain is suggested by descriptors such as burning, electric and shock-like with pain present in a region of sensory disturbance. Neuropathic pain often occurs in the absence of stimulation, and minor stimulation such as light touch can lead to exaggerated pain (allodynia).

| Nociceptive | Neuropathic | |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms |

* Dysaesthesia: unpleasant abnormal sensations, e.g. ants crawling under the skin.

It is also important to assess the contribution of psychological, spiritual and environmental factors. Assessment of psychological function includes determining disturbances in mood such as anxiety or depression. It also includes assessing the patient’s cognitions, such as their beliefs regarding the cause of their pain, their expectations and preferences for pain management, fear avoidance behaviours, lack of belief in their ability to function normally (self-efficacy), the level of relief they need in order to return to previous activities and the strategies they use to cope with their pain. Assessment of spiritual factors may be as simple as finding out what activities and relationships are important to the person and how these have been affected by the pain. This may help understand what gives them strength, purpose and meaning in their life. Further enquiries about a person’s beliefs and spiritual practices and how they influence or have been influenced by their experience of pain may also be helpful. Obtaining an environmental history focuses on elucidating any factors in their environment that may be contributing to the pain problem. It includes determining the social context of the patient, such as significant relationships, work, hobbies and activities and how these may be acting to reinforce the pain or hinder recovery.

PAIN HISTORY

A clear history will then provide the basis for further examination and investigations that further refine these preliminary observations. In addition, the history will provide clues regarding other aspects of the person’s presentation. The patient’s manner, tone, emphasis of certain facts, expressions and language will all help to convey important aspects of their expectations, understanding of their problem and emotional state. Although there are many variations on taking pain history, the basic elements consist of:

EXAMINATION

As mentioned above, biological pain generators can be broadly divided into nociceptive or neuropathic. Therefore the physical examination can be broadly divided along these same lines into musculoskeletal (or visceral) and neurological (Box 38.3). Other body systems (e.g. cardiovascular, respiratory and gastrointestinal) may also require examination, depending on the individual’s presentation. For example, a poor cardiovascular history in a person with low back pain should alert the clinician to the possibility of an underlying vascular cause. This would then warrant careful examination of the vascular system and, potentially, further investigation.

BOX 38.3 Physical examination

Examination of pain behaviours

Examination of the painful region

INVESTIGATIONS

A wide range of investigations may be indicated to complete an assessment of a patient presenting with persistent pain (Box 38.5). Unfortunately, while most investigations can demonstrate sinister pathology (e.g. fracture, infection, cancer and progressive neurological problems), they are less helpful in identifying the specific mechanisms that may be contributing to persistent pain. For example, in patients with spinal pain, it has been demonstrated that there is a poor correlation between pain report and the presence of pathology on anatomical imaging, even using sophisticated techniques such as magnetic resonance (MR) imaging of the spine.10,11 In patients with sciatica, imaging is recommended in the acute stage only if there are ‘red flags’ such as possible infection or malignancy rather than disc herniation, or in the person with severe symptoms who does not respond to 6–8 weeks of conservative management.12

BOX 38.5 Investigations

Clinical neurophysiology

May be useful in further characterising any neurological deficit. Useful tests include:

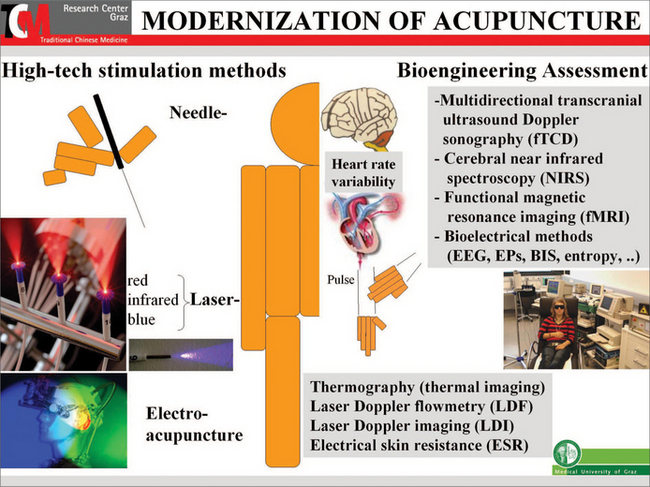

Thermography

Significant controversy surrounds the use of this technique in the assessment of persistent pain.13 Differences in skin temperature can be detected by using an infrared thermometer or thermal imaging.

However, measurement of temperature differences may be useful in conditions such as complex regional pain syndrome (CRPS) to detect autonomic dysfunction.14

MANAGEMENT OF PAIN

MINIMAL INTERVENTION: IS THIS A VALID OPTION?

Before examining available treatments, it is worth considering whether it is valid to ‘do nothing’ for the person with pain. A great danger for the practitioner facing the person in pain is feeling the need to do something to relieve the person’s suffering. While this is entirely appropriate in the acute pain setting, it may actually contribute to disability in those with persistent pain. In the semi-acute phase of low back pain, it has been demonstrated that long periods of rest have little benefit. Current guidelines indicate that the best approach is analgesia, short-term rest (up to 5 days) and encouragement to return to work (see Box 38.6). Over-medicalisation of chronic pain can lead to increased dependency on pharmacological approaches, increased healthcare practitioner visits, increased passivity and little gain in either pain relief or function.

BOX 38.6 Treatment of acute low back pain and sciatica12,15

HERBAL AND HOMEOPATHIC REMEDIES, VITAMINS AND SUPPLEMENTS

Complementary and alternative therapies are widely used in the management of chronic pain, and studies indicate that more than half the population use complementary approaches for the treatment of pain.16 However, many of the studies that have been done have low subject numbers, are not adequately controlled and have variability in design and outcome measures. Although there are a large number of remedies used, stronger evidence exists for:

PHARMACOLOGICAL

Although pharmacological approaches remain the mainstay of pain management (see Table 38.2), it is important to remember the holistic perspective on the management of pain. For example, where the experience of pain is being amplified by emotional, spiritual or existential concerns, the solution is to confront those issues as much as they can be and not merely to mask the problem with ever-escalating doses of medication while leaving the underlying issues unaddressed. Alternatively, providing sensitive and empathic emotional support is adjunctive to, but not a substitute for, the appropriate prescription of analgesics.

| Drug | Indications | Side effects |

|---|---|---|

| Paracetamol and NSAIDs | ||

| Paracetamol | ||

MAOIs: monamine oxidase inhibitors; NMDA: N-methyl-D-aspartate; NSAIDs: non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

The development of long-acting formulations such as slow- or controlled-release agents and transdermal patches has been an advance in providing more stable levels of analgesia. However, there are an increasing number of people now maintained on strong opioids who still report ongoing pain, with few gains in function and other effects such as alterations in endocrine function. This has led to increasing concerns and debate about the wisdom of this approach and has raised several issues.

In contrast to musculoskeletal pain, neuropathic pain generally responds poorly to anti-inflammatory medications, and opioids have reduced efficacy. Pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain relies on a number of other adjunctive medications.28 The two main classes are tricyclic antidepressants and anticonvulsants.

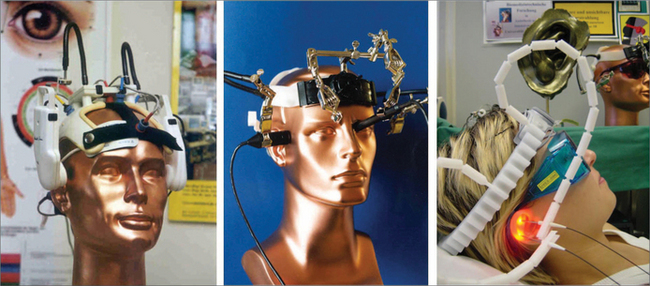

STIMULATION TECHNIQUES

PHYSICAL AND MANUAL THERAPIES

Although physical and manual therapies are widely used in the treatment of musculoskeletal pain problems (Table 38.3), there is continuing debate about their long-term effectiveness. There is stronger evidence for some approaches as indicated below:

| Nociceptive | Neuropathic |

|---|---|

| Pharmacological | |

As mentioned previously, the experience of pain is ‘holistic’ in that every part of our mental, emotional and physical make-up is affected when we experience chronic pain. Therefore the management of chronic pain needs to address the mind as well as the body. For this reason, mind–body practices such as mindfulness, hypnosis and relaxation therapies (see Box 38.7) can reduce hypervigilance, arousal and reactivity, and reduce anxiety or depression by helping to gently shift the focus of attention. Such adjunctive techniques have excellent long-term effects in the management of chronic pain and related symptoms for those who are motivated to use them.46–48

SPIRITUAL

There is wide variation in understanding as to what constitutes a spiritual approach to treatment (see Box 38.8), and very little evidence regarding the effectiveness of most treatments. Some people use the term to refer to treatments such as reiki, therapeutic touch or prayer that are believed to have a spiritual quality even when they are used simply with the aim of producing physical healing and symptomatic relief. On the other hand, spiritual approaches may refer to treatments or activities that are engaged in with the aim of addressing a person at a deeper, ‘spiritual’ level and trying to build qualities such as meaning, courage, gratitude and hope. For example, some people may find that music, art or a relationship with a higher power develops these qualities and gives them strength. People in pain can feel that they no longer have a meaningful purpose if activities and relationships they valued as important are lost or affected. It may be helpful to work with the person to develop a purpose beyond their pain which they recognise as meaningful. Using a spiritual approach then may include the process of identifying and fostering relationships and activities which strengthen a person’s spirit and provide the person with a purpose that again brings meaning and hope to their life. As mentioned previously, pain and suffering can actually be positive things by providing the person with the catalyst for change, and many people can emerge from pain and suffering with a deeper sense of meaning, strength and purpose.

SURGERY

Surgery has a major role in the treatment of pain, although results are usually poorer when the primary criterion for surgery is pain relief. Outcomes studies indicate that at 12 months there is little advantage of surgery over conservative management in the treatment of low back and sciatica.54 Therefore, while surgery may be indicated for those with severe pain, continuing neurological compromise and disability despite intensive conservative treatment, these studies suggest that the long-term outcomes between the two groups are similar. In addition, further surgical intervention in people with chronic back pain results in a decreasing likelihood of success with possible complications such as epidural fibrosis. Therefore, the promise of pain relief with re-operation is fraught with danger.

OTHER MEDICAL AND PARAMEDICAL APPROACHES

Because of the multifactorial nature of pain, treatment is often heavily reliant on input from other healthcare professionals. The treatment of pain, and chronic pain in particular, will often benefit from assessment and treatment in an interdisciplinary setting. Pain management centres can provide a comprehensive assessment with input from appropriately qualified practitioners such as rheumatologists, psychiatrists, neurologists, anaesthetists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, clinical psychologists, social workers, nurses and other specialties that have expertise in the underlying condition that may be giving rise to the pain. A comprehensive assessment may help to provide a holistic treatment plan that addresses the many factors involved in the pain problem. This can help to avoid the expense, frustration and disappointment that sometimes occur when people seek out a long list of various practitioners in the hope of finding the person who is going to take away their pain.

SELF-MANAGEMENT

Chronic pain is increasingly moving towards a self-management approach. Education by the primary care physician should encourage the person with chronic pain to manage the pain by themselves. Resources such as the book Manage Your Pain55 are available which provide the patient with active coping strategies to assist them to manage chronic pain effectively, with reduced reliance on healthcare professionals and medications. Other resources such as patient information sheets on acute low back pain and other acute musculoskeletal pain problems are available and can be downloaded from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia website (see the Resources list below).

CANCER PAIN: SPECIFIC ISSUES

Berman BM. Integrative approaches to pain management: how to get the best of both worlds. BMJ. 2003;326(7402):1320-1321.

Handbook for Health Professionals. Ch 17, Managing chronic pain. Department of Health and Ageing. Online. Available: http://www.aodgp.gov.au/internet/aodgp/publishing.nsf/content/pain-1.

National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Evidence-based management of acute musculoskeletal pain. Online. Available: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/cp94syn.htm.

National Health & Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Acute pain management: scientific evidence. Online. Available: http://www.nhmrc.gov.au/publications/synopses/cp104syn.htm.

Nicholas MK, Molloy A, Beeston L, et al. Manage your pain. Sydney: ABC Books, 2007.

Patel G, Euler D, Audette JF. Complementary and alternative medicine for non-cancer pain. Med Clin North Am. 2007;91(1):141-167.

Therapeutic guidelines: Analgesic. Version 5. Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd, 2007.

1 Blyth FM, March LM, Brnabic AJM, et al. Chronic pain in Australia: a prevalence study. Pain. 2001;89:127-134.

2 Siddall PJ, Cousins MJ. Persistent pain as a disease entity: implications for clinical management. Anesth Analg. 2004;99(2):510-520.

3 Turk DC. The role of psychological factors in chronic pain. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 1999;43:885-888.

4 Singer T, Seymour B, O’Doherty J, et al. Empathy for pain involves the affective but not sensory components of pain. Science. 2004;303(5661):1157-1162.

5 Eriksen HR, Ursin H. Subjective health complaints, sensitization, and sustained cognitive activation (stress). J Psychom Res. 2004;56(4):445-448.

6 Ursin H, Eriksen HR. Sensitization, subjective health complaints, and sustained arousal. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2001;933:119-129.

7 Elias AN, Wilson AF. Serum hormonal concentrations following transcendental meditation—potential role of gamma aminobutyric acid. Med Hypotheses. 1995;44(4):287-291.

8 Harte JL, Eifert GH, Smith R. The effects of running and meditation on beta-endorphin, corticotrophin-releasing hormone and cortisol in plasma, and on mood. Biol Psychol. 1995;40(3):251-265.

9 Rippentrop AE, Altmaier EM, Chen JJ, et al. The relationship between religion/spirituality and physical health, mental health, and pain in a chronic pain population. Pain. 2005;116(3):311-321.

10 Jensen MC, Brant-Zawadzki MN, Obuchowski N, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lumbar spine in people without back pain. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:69-73.

11 Schellhas KP, Smith MD, Gundry CR, et al. Cervical discogenic pain: prospective correlation of magnetic resonance imaging and discography in asymptomatic subjects and pain sufferers. Spine. 1996;21:300-312.

12 Koes BW, van Tulder MW, Peul WC. Diagnosis and treatment of sciatica. BMJ. 2007;334(7607):1313-1317.

13 LaBorde TC. Reimbursement for unproven therapies: the case of thermography. JAMA. 1993;270(21):2558-2559.

14 Rommel O, Habler H-J, Schurmann M. Laboratory tests for complex regional pain syndrome. Wilson P, Stanton-Hicks M, Harden RN, editors. CRPS: current diagnosis and therapy, progress in pain research and management, Vol. 32. Seattle: IASP Press, 2005.

15 de Jager JP, Ahern MJ. Improved evidence-based management of acute musculoskeletal pain: guidelines from the National Health and Medical Research Council are now available. Med J Aust. 2004;181(10):527-528.

16 Patel G, Euler D, Audette JF. Complementary and alternative medicine for noncancer pain. Med Clin North Am. 2007;91(1):141-167.

17 Chrubasik S, Eisenberg E, Balan E, et al. Treatment of low back pain exacerbations with willow bark extract: a randomized double-blind study. Am J Med. 2000;109(1):9-14.

18 Gagnier JJ, vanTulder M, Berman B, et al. Herbal medicine for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2:CD004504.

19 Clegg DO, Reda DJ, Harris CL, et al. Glucosamine, chondroitin sulfate, and the two in combination for painful knee osteoarthritis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(8):795-808.

20 Altman RD, Marcussen KC. Effects of a ginger extract on knee pain in patients with osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2001;44(11):2531-2538.

21 Soeken KL. Selected CAM therapies for arthritis-related pain: the evidence from systematic reviews. Clin J Pain. 2004;20(1):13-18.

22 Little CV, Parsons T, Logan S. Herbal therapy for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;1:CD002947.

23 Fortin P, Lew R, Liang M, et al. Validation of a meta-analysis: the effects of fish oil in rheumatoid arthritis. J Clin Epidemiol. 1995;48(11):1379-1390.

24 Pittler MH, Ernst E. Peppermint oil for irritable bowel syndrome: a critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93(7):1131-1135.

25 Gokhale L. Curative treatment of primary (spasmodic) dysmenorrhoea. Indian J Med Res. 1996;103:227-231.

26 Proctor ML, Murphy PA. Herbal and dietary therapies for primary and secondary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;3:CD002124.

27 Department of Health and Ageing. Substance abuse assessment. A manual of mental health care in general practice; 2003. Online. Available: http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-pubs-m-mangp-toc~mental-pubs-m-mangp-18~mental-pubs-m-mangp-18-as.

28 Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Backonja M, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132(3):237-251.

29 Proctor ML, Smith CA, Farquhar CM, et al. Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation and acupuncture for primary dysmenorrhoea. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;1:CD002123.

30 Bjordal J, Johnson M, Lopes-Martins R, et al. Short-term efficacy of physical interventions in osteoarthritic knee pain. A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2007;8(1):51.

31 Chow RT, Heller GZ, Barnsley L. The effect of 300 mW, 830 nm laser on chronic neck pain: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Pain. 2006;124(1/2):201-210.

32 Smith CA, Collins CT, Cyna AM, et al. Complementary and alternative therapies for pain management in labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD003521.

33 Melchart D, Linde K, Fischer P, et al. Acupuncture for idiopathic headache. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;1:CD001218.

34 Berman BM, Ezzo J, Hadhazy V, et al. Is acupuncture effective in the treatment of fibromyalgia? J Fam Pract. 1999;48(3):213-218.

35 Guerra de Hoyos JA, Andres Martin MdC, Bassas Y, Baena de Leon E, et al. Randomised trial of long term effect of acupuncture for shoulder pain. Pain. 2004;112(3):289-298.

36 Trinh KV, Phillips SD, Ho E, et al. Acupuncture for the alleviation of lateral epicondyle pain: a systematic review. Rheumatology. 2004;43(9):1085-1090.

37 Trinh KV, Graham N, Gross AR, et al. Acupuncture for neck disorders. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD004870.

38 Furlan AD, van Tulder M, Cherkin D, et al. Acupuncture and dry-needling for low back pain: an updated systematic review within the framework of the Cochrane collaboration. Spine. 2005;30(8):944-963.

39 Jull G, Trott P, Potter H, et al. A randomized controlled trial of exercise and manipulative therapy for cervicogenic headache. Spine. 2002;27(17):1835-1843.

40 Pengel LHM, Refshauge KM, Maher CG, et al. Physiotherapist-directed exercise, advice, or both for subacute low back pain: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007;146(11):787-796.

41 Cherkin DC, Eisenberg D, Sherman KJ, et al. Randomized trial comparing traditional Chinese medical acupuncture, therapeutic massage, and self-care education for chronic low back pain. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(8):1081-1088.

42 Chou R, Huffman LH, American Pain Society, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(7):492-504.

43 Schonstein E, Kenny DT, Keating J, et al. Work conditioning, work hardening and functional restoration for workers with back and neck pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;1:CD001822.

44 Sherman KJ, Cherkin DC, Erro J, et al. Comparing yoga, exercise, and a self-care book for chronic low back pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(12):849-856.

45 Keller E, Bzdek V. Effects of therapeutic touch on tension headache pain. Nurs Res. 1986;35(2):101-106.

46 Kabat-Zinn J, Lipworth L, Burney R. The clinical use of mindfulness meditation for the self-regulation of chronic pain. J Behav Med. 1985;8(2):163-190.

47 Carmody J, Baer RA. Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms of well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. J Behav Med. 2008;31(1):23-33.

48 Gonsalkorale WM, Miller V, Afzal A, et al. Long-term benefits of hypnotherapy for irritable bowel sundrome. Gut. 2003;52(11):1623-1629.

49 Morley S, Eccleston C, Williams AC. Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials of cognitive behaviour therapy and behaviour therapy for chronic pain in adults, excluding headache. Pain. 1999;80:1-13.

50 Suls J, Wan C. Effects of sensory and procedural information on coping with stressful medical procedures and pain: a meta-analysis. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1989;57(3):372-379.

51 Luebbert K, Dahme B, Hasenbring M. The effectiveness of relaxation training in reducing treatment-related symptoms and improving emotional adjustment in acute non-surgical cancer treatment: a meta-analytical review. Psycho-Oncology. 2001;10(6):490-502.

52 Miro J, Raich RM. Effects of a brief and economical intervention in preparing patients for surgery: does coping style matter? Pain. 1999;83(3):471-475.

53 Cepeda MS, Carr DB, Lau J, et al. Music for pain relief. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2:CD004843.

54 Peul WC, van Houwelingen HC, van den Hout WB, et al. Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(22):2245-2256.

55 Nicholas MK, Molloy A, Beeston L, et al. Manage your pain. Sydney: ABC Books, 2007.

56 World Health Organization. Cancer pain relief. Geneva: WHO, 1986.