14 Malnutrition

Clinical Presentation

Chronic malnutrition is identified by low height for age, also known as stunting. Chronically malnourished children are shorter than other children their age and may fail to meet their long-term growth potential. Acute malnutrition is characterized by low weight for height and low MUAC with or without symmetric edema. Severe acute malnutrition is defined as severe wasting, nutritional edema, or both. An acutely malnourished child has low body fat reserves and may also have limited protein stores. Children with severely low levels of serum protein often develop symmetric edema. Table 14-1 displays criteria used to define moderate and severe malnutrition. This chapter uses the World Health Organization (WHO) definitions to classify the severity of malnutrition. It is common for stunting and wasting to occur concomitantly. Children with combined chronic and acute malnutrition are both short for age and thin for height.

Table 14-1 World Health Organization Criteria for Defining Moderate and Severe Malnutrition

| Moderate Malnutrition | Severe Malnutrition | |

|---|---|---|

| Height for age | −3 to −2 SD below the mean (85th to 89th percentile) | <−3 SD below the mean (<85th percentile) |

| Weight for height | −3 to −2 SD below the mean (70th to 79th percentile) | <−3 SD below the mean (<70th percentile) |

| Symmetric edema | No | Yes |

SD, standard deviation.

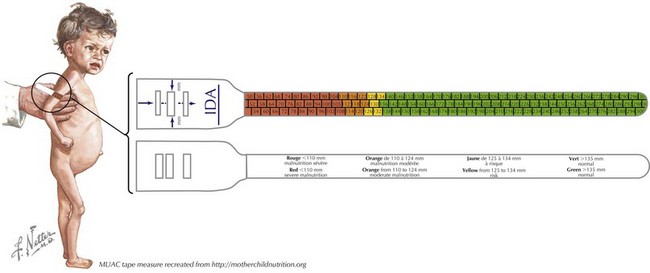

Scales for assessing weight, stadiometers for measuring height, and tape measures for evaluating MUAC are all essential tools in settings where severe malnutrition is diagnosed and managed. Growth charts (discussed in Chapter 13) are also necessary to allow for the quantification of the degree of malnutrition. In very low-resource settings when scales are not available, MUAC tapes alone may be used to screen for and follow up severe acute malnutrition (Figure 14-1).

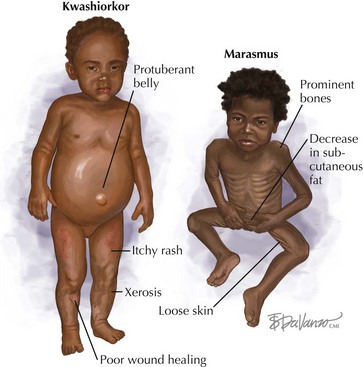

The three common forms of protein-energy malnutrition are marasmus, kwashiorkor, and a mixed form called marasmic kwashiorkor. Whereas marasmus is typically considered to be a reflection of caloric deficiency, kwashiorkor is thought to be reflective primarily of a deficiency of protein. Marasmus can be recognized visually by decreased subcutaneous fat leading to prominent bones and the appearance of “loose skin,” especially around the buttocks. Kwashiorkor is characterized by bilateral pitting edema and a protuberant belly (Figure 14-2). Malnutrition is commonly associated with visible hair and skin changes. The hair is commonly thin, scanty, straight, and lightly pigmented. Skin changes are varied and commonly include xerosis, itchy rashes, and poor wound healing.

Other physical examination findings that are commonly seen with severe malnutrition are outlined in Table 14-2.

Table 14-2 Common Physical Examination Findings in Severe Acute Malnutrition

| Physical Finding | Significance |

|---|---|

| Low height for age |

MUAC, mid-upper arm circumference.

Differential Diagnosis

When diagnosing malnutrition, underlying causes should be investigated. Infections with HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, and parasites commonly cause or exacerbate malnutrition. Failure to identify and treat these underlying conditions would prohibit appropriate recovery. Other common causes of severe malnutrition can be found in Chapter 17, specifically Table 17-1.

Physiologic Changes Accompanying Malnutrition

Profound physiologic changes occur in children with severe acute malnutrition. All body systems undergo significant functional changes with severe malnutrition. Table 14-3 outlines some of the most significant physiologic changes that occur with severe acute malnutrition and the treatment approaches that are necessary to avoid complications related to these physiologic abnormalities.

Table 14-3 Major Physiologic Changes with Severe Acute Malnutrition

| Body System | Major Physiologic Changes | Treatment Approaches |

|---|---|---|

| Cardiovascular |

IV, intravenous.

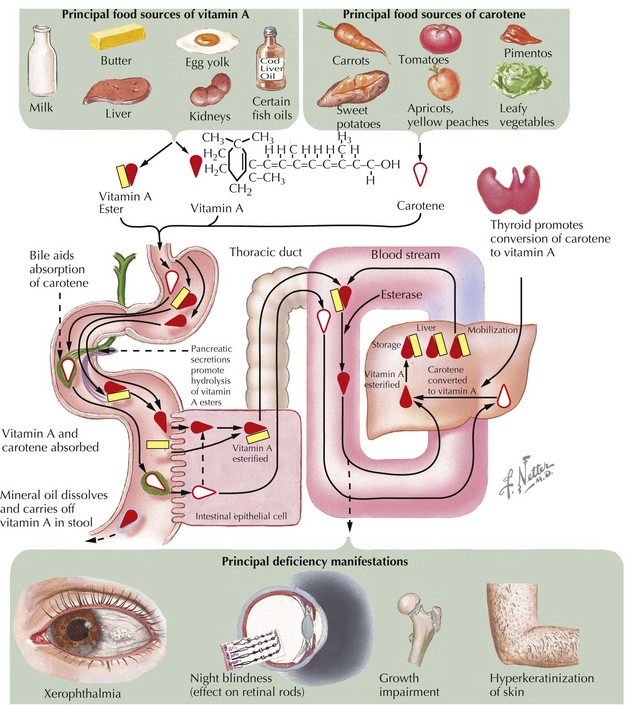

Micronutrient deficiencies are also common among children with severe malnutrition. Vitamin A deficiency should be assumed to be present, and high-dose vitamin A should be provided on day 1 of treatment. For infants younger than 6 months of age, a high-dose vitamin A is 50,000 IU; 100,000 IU should be given to infants between 6 and 12 months, and 200,000 IU should be given to children over 12 months of age. When clinical signs of vitamin A deficiency are present, an additional large dose of vitamin A should be given on day 2 of rehabilitation and a third dose about 2 weeks later. Ocular signs of vitamin A deficiency are often easily recognizable and include night blindness, conjunctival xerosis with foamy white Bitot’s spots, keratomalacia, and corneal ulceration (Figure 14-3).

Management

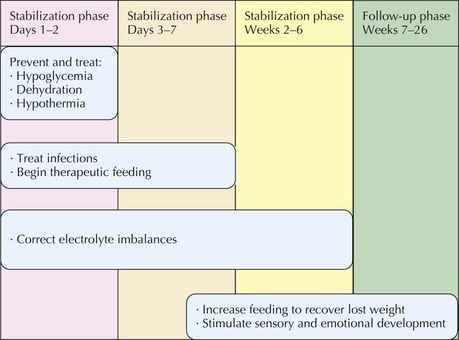

A severely malnourished child is also often severely ill, and management must progress through stages of recovery. The first week of treatment for severe malnutrition is referred to as the stabilization phase because appropriate management during this period makes the child less vulnerable to malnutrition-related death and is critical for survival. There are physiologic differences between a healthy child and a severely malnourished child that must be taken into account in devising management plans during at least the first 6 weeks of rehabilitation. Close follow-up of a malnourished child should continue for at least 6 months after presentation with severe malnutrition. Figure 14-4 outlines the main goals of each phase of management of a severely malnourished child.

Ashworth A. Efficacy and effectiveness of community-based treatment of severe malnutrition. Food Nutr Bull. 2006;27(3 suppl):S24-S48.

Chagan M, Berkley JA, Rollins N, et al. Blantyre Working Group: Case management of HIV-infected severely malnourished children: challenges in the area of highest prevalence. Lancet. 2008;371(9620):1305-1307.

Collins S, Dent N, Binns P, et al. Management of severe acute malnutrition in children. Lancet. 2006;368(9551):1992-2000.

World Health Organization. Community-Based Management of Severe Acute Malnutrition. Available at www.who.int/nutrition/publications/severemalnutrition/en/

World Health Organization. Management of Severe Malnutrition: A manual for Physicians and Other Senior Health Workers. Geneva: WHO Library; 2009.