Chapter 45 Malignant melanoma

DevCan: Probability of developing or dying of cancer software, version 6.2.1, Statistical Research and Applications Branch, NCI, 2007. Available at: http://srab.cancer.gov/devcan. Accessed July 28, 2010.

Tucker MA: Melanoma epidemiology, Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 23:383–395, 2009.

Meyle KD, Guldberg P: Genetic risk factors for melanoma, Hum Genet 126:499–510, 2009.

Genetic factors include past medical history of melanoma, familial medical history of melanoma in a first-degree relative, Fitzpatrick type I or II skin, large congential nevi, the presence of dysplastic (atypical) nevi, >50 benign nevi (>2 mm in size), xeroderma pigmentosum, and familial dysplastic mole syndrome (FDMS). In FDMS, which is defined as occurring in families with atypical nevi and two or more blood relatives with melanoma, the estimated prevalence of melanoma approaches 85% by age 48. It is noteworthy that variations in the melanocortin receptor 1 (MCR1) gene, which is a component of pigment diversity, also confer an increased risk of melanoma. Variants differ in their associations with melanoma and nonmelanoma skin cancer, but both red hair and non–red hair variants confer increased risk.

Friedman RJ, Farber MJ, Warycha MA, et al: The “dysplastic” nevus. Clin Dermatol 27:103–115, 2009.

Elder, DE: Dysplastic nevi: an update, Histopathology 56:112–120, 2010.

La Porta C: Cancer stem cells: lessons from melanoma, Stem Cell Rev 5(1):61–65, 2009.

Key Points: Diagnosis of Malignant Melanoma

Bauer J, Bastian B: Genomic analysis of melanocytic neoplasia, Adv Dermatol 21:81–99, 2005.

Campos-do-Carmo G, Ramos-e-Silva M: Dermoscopy: basic concepts, Int J Dermatol 47:712–719, 2008.

Piris A, Mihm MC Jr: Progress in melanoma histopathology and diagnosis, Hematol Oncol Clin North Am 23:467–480, 2009.

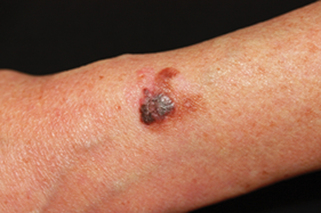

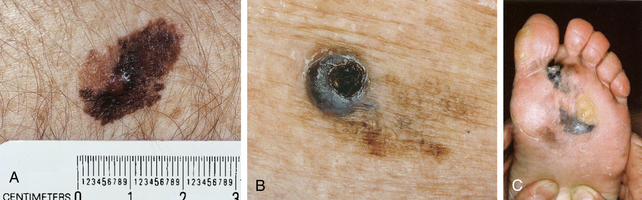

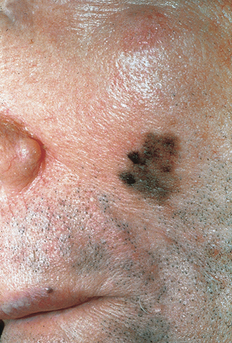

Pathology remains the gold standard for the diagnosis of melanoma. To establish a histologic diagnosis, the suspect lesion should be completely excised with a 1- to 3-mm margin of skin to the depth of the subcuticular fat. If this is not possible, due to anatomic location or size of the lesion, an incisional or punch biopsy to the depth of the subcuticular fat should be performed on the thickest or most atypical portion of the lesion. It is noteworthy that biopsy of lentigo maligna can be problematic, because there are often skip areas, as well as areas of regression, in these lesions that may lead to misdiagnosis. The best biopsy technique to establish the diagnosis of lentigo maligna is usually multiple punch biopsies from different sites or broad shave biopsy from multiple areas.

Zitelli JA: Surgical margins for lentigo maligna, Arch Dermatol 2004 140:607–608, 2004.

To date there is little evidence that early dissection in SLN positive patients improves their survival compared to patients who receive nodal dissection when clinically detectable nodes develop. SLN remains a very controversial topic, and several points need to be emphasized. First, there is little evidence to suggest that melanoma cells migrate in an orderly fashion toward the draining lymph node, and the presence of melanoma cells within a lymph node may merely be an indicator of systemic metastatic disease. Second, surgical alteration of a patient’s regional lymphatic structure may impair the body’s immune response to melanoma. Third, at present we are unable to determine what constitutes relevant nodal disease. In this regard, 60% of patients with primary melanoma <1.0 mm in depth demonstrate positive SLN through polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis. These patients have a very favorable survival rate and rarely go on to develop nodal disease. Therefore, the presence of microscopic metastases does not correlate with the clinical course. Fourth, SLN biopsies require close collaboration between the nuclear radiologist, surgeon, and pathologist. Patient selection is also paramount. This procedure is less reliable if a wide excision has been performed; therefore, patients considered candidates should be referred for this procedure prior to the wide excision, which can be carried out simultaneously with the SLNB. Fifth, lymphatic flow is markedly varied in different persons, and it is difficult to predict with any degree of certainty which nodal basin serves a particular area of skin. Lastly, proponents of SLNB argue that SLN may identify patients who may be candidates for adjuvant therapy (see below). Nevertheless, to date no effective adjuvant therapy exists for metastatic melanoma.

Zitelli JA: Sentinel lymph node biopsy: an alternate view, Dermatol Surg 34:544–549, 2008.

Baran R, Kechijian P: Hutchinson’s sign: a reappraisal, J Am Acad Dermatol 44:87–90, 2001.

Wolchok JD, Saenger YM: Current topics in melanoma, Curr Opin Oncol 19:116–120, 2007.

A number of new mAbs are directed against various targets, including vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), tumor necrosis family costimulatory receptors (e.g., DR4, DR5, glucocorticoid-induced tumor necrosis factor receptor [GITR], CD134 [OX40], CD137 [4-1BB], and CD40), and integrins also are currently being investigated in clinical trials.

Tawbi H, Nimmagadda N: Targeted therapy in melanoma, Biologics 3:475–484, 2009.