8 Malignant disease

Approach to the patient with cancer

Symptoms

Patients can present in a number of ways:

Performance status

This is a measurement of a patient’s overall functional status. It helps to predict how a treatment will be tolerated and also response to treatment. Performance status is commonly measured using the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group scale (Table 8.1) or the Karnofsky scale.

Table 8.1 Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status scale

| Status | Description |

|---|---|

| 0 | Asymptomatic, fully active and able to carry out all pre-disease performance without restrictions |

| 1 | Symptomatic, fully ambulatory but restricted in physically strenuous activity, able to carry out performance of light or sedentary nature e.g. light housework, office work |

| 2 | Symptomatic, ambulatory and capable of all self-care but unable to carry out any work activities. Up and about > 50% of waking hours; in bed < 50% of day |

| 3 | Symptomatic, capable of only limited self-care, confined to bed or chair > 50% of waking hours, but not bedridden |

| 4 | Completely disabled, cannot carry out any self-care. Totally bedridden |

Investigations

These should be aimed at confirming the presence of malignancy and assessing the extent of spread (i.e. staging the tumour). Although tumours may have a characteristic radiological appearance, biopsy with histology should always be performed, as the prognosis and treatments of different cancers vary greatly. Different tumours are staged in different ways. The most commonly used staging system for solid tumours is the TNM (tumour, node, metastases) system, which is updated every few years (Box 8.6, p. 269).

Cancer treatment

• Types of treatment

• Measuring response to treatment (Box 8.1)

Box 8.1 Definitions of response (RECIST)

| • Complete response | Complete disappearance of all detectable disease |

| • Partial response | At least a 30% decrease in the sum of diameters of target lesions, taking as reference the baseline sum diameters |

| • Stable disease | Neither sufficient shrinkage to qualify for PR nor sufficient increase to qualify for PD |

| • Progressive disease | At least a 20% increase in the sum of diameters of target lesions, or the appearance of new lesions |

Principles of radiation treatment

Administration of radiotherapy

Radiotherapy regimes

Side-effects are shown in Box 8.3.

Box 8.3 Potential side-effects of radiotherapy

Acute (during and up to 90 days)

| • Skin | Erythema, hair loss, dry desquamation, moist desquamation |

| • Gastrointestinal tract | Nausea, anorexia, mucositis, oesophagitis, diarrhoea, proctitis |

| • Genitourinary tract | Cystitis, urinary frequency, nocturia, urgency |

Late (after 90 days)

| • Skin | Pigmentation, telangiectasia, atrophy |

| • Bone | Necrosis, sarcoma |

| • Mouth | Xerostomia, osteoradionecrosis |

| • Bowel | Diarrhoea, stenosis, fistula |

| • Bladder | Fibrosis, fistula |

| • Vagina | Stenosis |

| • Lung | Fibrosis |

| • Heart | Pericardial reactions, cardiomyopathy |

| • CNS | Myelopathy |

| • Reproductive | Infertility, premature menopause, impotence |

Principles of chemotherapy

Chemotherapy drugs are commonly given in combination (Table 8.2); the rationale for this is two-fold. Firstly, if drugs with differing mechanisms of action are used, which act at differing stages of the cell cycle, this can maximize the number and types of cancer cells killed. In addition, some drug combinations may have synergistic effects. Secondly, the simultaneous use of multiple drugs reduces the risk of drug resistance developing and the survival chances of the tumour.

| Malignancy | Regimen | Components |

|---|---|---|

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | ABVD | Doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine |

| BEACOPP | Bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, prednisolone | |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | CHOP | Cyclophosphamide, hydroxy-doxorubicin, vincristine, prednisolone |

| Breast cancer | FEC | 5-FU, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide |

| FEC-T | 5-FU, epirubicin, cyclophosphamide followed by docetaxel | |

| TAC | Docetaxel, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide | |

| Lung cancer | PE | Cisplatin, etoposide |

| GC | Gemcitabine, carboplatin | |

| Stomach cancer | ECF | Epirubicin, cisplatin, 5-FU |

| Colorectal cancer | FolFOx | Oxaliplatin, 5-FU, folinic acid |

| OX | Oxaliplatin, capecitabine |

Administration of chemotherapy drugs

Available chemotherapeutic drugs

• DNA-damaging agents

• DNA repair inhibitors

Side-effects of treatment

| Emeto-genicity | On days of chemotherapy | Days after chemotherapy |

|---|---|---|

| Low | No antiemetic required routinely Metoclopramide 10 mg 3 times daily or domperidone 20 mg 3 times daily if the patient experiences nausea and vomiting |

|

| Moderate | Metoclopramide 20 mg IV oral 3 times daily or domperidone 20 mg oral 3 times daily Dexamethasone 4–8 mg IV/oral daily |

Metoclopramide or domperidone 20 mg 3 times daily for 3 days, then as required Dexamethasone 4 mg twice daily for 2 days |

| High | Granisetron 1 mg IV/oral 1–2 times daily Dexamethasone 8–16 mg IV/oral daily (in 1 or 2 divided doses) |

Metoclopramide or domperidone 20 mg 3 times daily for 3–5 days, then as required Dexamethasone 4 mg twice daily for 2–3 days Granisetron 1 mg twice daily for 2 days |

Box 8.5 Managing a febrile neutropenic patient

Principles of high-dose therapy

In chemosensitive tumours, the administration of high doses of chemotherapy maximizes their cytotoxic effect, but their limiting effect is bone marrow toxicity and susceptibility to infections. Haematopoietic stem cells are often infused into the patient to shorten the neutropenic period, which may last 2–3 weeks. The patient is reverse barrier-nursed in isolation, preferably in a negative air pressure-ventilated room.

Allogeneic stem cell transplantation

Transplant complications

Principles of endocrine therapy

Breast cancer (p. 270)

Prostate cancer (p. 276)

Principles of targeted treatments

The treatment of malignancy has been revolutionized by the advent of molecularly targeted treatments that inhibit the tyrosine kinase (TK) pathway. These treatments aim to exploit tumour-specific over-expression of epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR), deranged and chaotic tumour vasculature and supporting extracellular matrix. Inhibition is achieved directly (using small molecules) or indirectly (using monoclonal antibodies). These treatments present an opportunity in the future to provide patient-specific treatment, reduce side-effect profiles and improve outcome.

Selective targets (Table 8.4)

Monoclonal antibodies

Table 8.4 Targeted therapies (cytokine modulation) used in cancer treatment

| Drug | Target | Malignancy |

|---|---|---|

| Cetuximab | Anti-EGFR | Colorectal cancer Head and neck |

| Bevacizumab | Anti-VEGF | Colorectal cancer |

| Rituximab | Anti-CD20 | Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

| Alemtuzamab | Anti-CD52 | Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia |

| Trastuzumab | Anti-Her2 | Breast cancer |

| Imatinib | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Chronic myeloid leukaemia Gastrointestinal stromal tumours |

| Gefitinib | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor EGFR |

Non-small cell lung cancer |

| Erlotinib | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Non-small cell lung cancer Bronchoalveolar cancer |

| Dasatinib | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Chronic myeloid leukaemia |

| Sorafenib | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Renal cell cancer |

| Sunitinib | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Renal cell cancer |

| Nilotinib | Tyrosine kinase inhibitor | Chronic myeloid leukaemia |

| Bortezomib | Proteosome inhibitor | Myeloma |

| Panitumumab | EGFR | Metastatic colorectal cancer |

| Bexarotene | Retinoid X receptor agonist | Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma |

EGFR, epidermal growth factor receptor; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Immunotherapeutic agents

Common solid tumour management

Lung cancer

Treatment of non-small cell lung cancer

• Palliative treatment

Breast cancer

Investigations

Prognosis

In early breast cancer the prognosis can be predicted from the factors listed above, and the survival probability and benefit from adjuvant therapy by using the website www.adjuvantonline.com. The 10-year survival can vary from > 90% for small, low-grade, node-negative tumours to < 20% for large, high-grade tumours with more than three nodes involved, if no adjuvant treatment is given.

Local treatment

• Adjuvant systemic treatment

Treatment of metastatic breast cancer

Gastrointestinal cancers

Colorectal carcinoma

• Rectal tumours

Oesophageal cancer

Gastric cancer

Gynecological malignancy

Epithelial ovarian cancer

Endometrial cancer

Cervical cancer

Genitourinary malignancies

Prostate cancer

• Treatment for localized disease

• Treatment for metastatic disease

Bladder cancer

Testicular germ cell tumours

• Treatment of patients with advanced disease

Renal cell cancer (RCC)

Hodgkin’s lymphoma

| • lymphocyte-predominant (LP) |

| • nodular sclerosing (NS) |

| • mixed cellularity (MC) |

| • lymphocyte-depleted (LD). |

Treatment

Late complications of treatment

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL)

Indolent B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Intermediate and high-grade lymphoma

Burkitt’s lymphoma

Primary extranodal lymphoma

Management of leukaemia

Acute leukaemia

Acute myeloid leukaemia (AML)

• Treatment

Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia (ALL)

Chronic leukaemia

Chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML)

CML is a clonal malignant myeloproliferative disorder, which originates from an early haematopoietic progenitor cell. The progeny of this stem cell proliferates over a period of months to years and when the leukaemia is diagnosed the peripheral blood white cell count is characteristically raised with granulocytes at all stages of development. CML accounts for 14% of all leukaemias and its peak incidence is at 40–60 years. It very rarely occurs in children. CML is characterized cytogenetically by a balanced translocation between chromosomes 9 and 22, t(9;22)(q23;q11.2). The resultant chromosome is known as the Philadelphia chromosome (ph) and gives rise to a chimeric gene, BCR-ABL. This in turn translates into a fusion protein product with increased TK activity, which plays a pivotal role in the pathophysiology of CML.

• Treatment

Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL)

• Treatment of disease complications

Multiple myeloma

Diagnosis

Two out of three diagnostic features should be present:

A low β2 microglobulin and an albumin of about 35 g/L are of good prognostic value.

Treatment

• Patients eligible for HD chemotherapy and PBSCR

Treatment of complications

Oncological emergencies

Malignant hypercalcaemia

Malignant hypercalcaemia (see Box 15.3, p. 588) may complicate up to 10% of all cancers, especially breast, squamous cell carcinoma of lung and myeloma.

Palliative care and symptom control

Pain

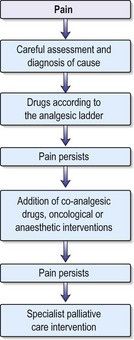

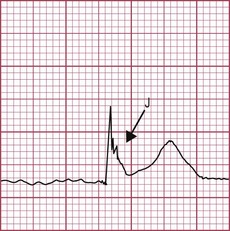

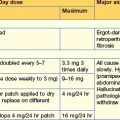

Around 70% of cancer patients experience moderate to severe pain during the course of their disease, but with conventional analgesia this can be well controlled in most. The principles of good pain management include careful assessment of the nature and cause of the pain, instigation of analgesics according to the WHO analgesic ladder and regular review of the effectiveness of the drugs prescribed (Fig. 8.1). WHO has developed a three-step analgesic ladder for cancer pain relief. If patients complain of pain, they should be started on medication as recommended on the first step of the ladder and then moved up to subsequent steps until their pain is under control.

Strong opioid drugs

Morphine is the most commonly used strong opioid and is given by mouth. It is available as an oral solution or as an immediate-release tablet and is given regularly every 4 hours. When a patient commences morphine, a starting dose of 5–10 mg is commonly used; however, if it is replacing a stronger analgesic, a higher starting dose is necessary. If the patient’s pain is relieved by morphine but the relief is not sustained until the next dose, the dose is increased by 50% until the pain is controlled. Once the patient’s 24-hour morphine requirements have been established, this dose can be converted to a controlled-release preparation, which is then administered once or twice a day. For example:

• Side-effects

Gastrointestinal symptoms

| Cause | Antiemetic |

|---|---|

| Gastric stasis | Metoclopramide (10–20 mg 4 times daily) |

| Treatment-related (chemotherapy*, radiotherapy†) | Domperidone (20 mg 3 times daily), dexamethasone (4 mg twice daily), metoclopramide, ondansetron (8 mg twice daily), granisetron (1 mg twice daily), levomepromazine (3.175 mcg–25 mcg/24 hours) |

| Bowel obstruction | Cyclizine (50 mg 3 times daily), haloperidol (1.5 mg 1–2 times daily), levomepromazine (3.175 mcg–25 mcg/24 hours) |

* Different chemotherapy regimes are classed as being of low, moderate and high emetogenicity. The type, combination and duration of antiemetic will be given prophylactically according to regime.

† If radiotherapy-induced nausea is due to small bowel being irradiated, a 5HT3 antagonist is usually necessary.

Respiratory symptoms

Breathlessness can be a very distressing symptom in cancer patients and the underlying cause should be identified and treated if possible. Antibiotics may be used to treat respiratory infections, pleural and pericardial effusions may be drained and symptomatic anaemia transfused. Breathlessness at rest may be partly relieved by regular doses of oral morphine starting at 5 mg every 4 hours. If the breathlessness is associated with anxiety, diazepam 5–10 mg daily may also be of benefit. If there is significant bronchospasm or obstruction, corticosteroids are helpful. Excessive respiratory secretions occur frequently in the terminal stages of cancer and are sometimes referred to as the death rattle. For these patients SC infusion of hyoscine hydrobromide 0.6–2 mg/24 hours may be helpful.

Benson JR, et al. Early breast cancer. Lancet. 2009;373:1463-1479.

Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG). Effects of chemotherapy and hormonal therapy for early breast cancer on recurrence and 15-year survival: an overview of the randomised trials. Lancet. 2005;365(9472):1687-1717.

Elwood PC, et al. Aspirin, salicylates and cancer. Lancet. 2009;373:1301-1309.

Guppy AE, Nathan PD, Rustin GJ. Epithelial ovarian cancer: a review of current management. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol). 2005;17(6):399-411.

Madoff RD. Rectal cancer: optimal treatments leads to optimal results. Lancet. 2009;373:811-820.

Sarssain C, et al. CNS complications of radiotherapy and chemotherapy-review. Lancet. 2009;374:1639-1651.

weeks, with intracavitary treatment given to boost the dose to the cervix.

weeks, with intracavitary treatment given to boost the dose to the cervix.