Chapter 3 Malignancies of the Temporal Bone—Limited Temporal Bone Resection

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Videos corresponding to this chapter are available online at www.expertconsult.com.

Historically, carcinoma of the temporal bone was an ominous diagnosis. Advancements in diagnostic and surgical technique have led to greatly improved outcomes. The successful resection of T1 disease has shown survival outcomes of 95%, and the treatment of T2 and T3 disease has shown survivals of 85% when a clear surgical margin is combined with postoperative radiation therapy.1

A multidisciplinary approach to the diagnosis and treatment of these lesions offers the best possible outcome. Surgery and postoperative radiation represent the principal treatment arms; however, interest in a possible combined role for chemotherapy is increasing.2 The type of resection needed is determined by the extent of disease. A sound oncologic resection can be achieved through a lateral temporal bone resection, subtotal temporal bone resection, or total temporal bone resection with such additional simultaneous procedures as parotidectomy, facial nerve resection, mandibulectomy, and cervical lymphadenectomy as indicated. When the surgery has been planned, reconstructive options should be explored. Great strides have been made over the past century in the surgical and nonsurgical management of temporal bone neoplasms, but they remain a significant treatment challenge.

TUMOR CONSIDERATIONS

The incidence of tumors of the temporal bone is 200 new cases per year with a frequency of 6 cases per 1 million. Squamous cell carcinoma accounts for 86% of these tumors. Possible etiologic factors include industrial exposure to petroleum-based products, topical disinfectants, and chronic infection. Basal cell carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, adenocarcinoma, and ceruminous carcinoma occur less frequently.3–5 Tumors of mesenchymal origin are as rare, with rhabdomyosarcoma occurring most frequently.6 Salivary gland tumors can originate from ectopic rests of salivary tissue within the middle ear (pleomorphic adenoma has been described in that location), or from minor salivary glands within the EAC, but both are rare.7

Salivary gland tumors are more likely to involve the temporal bone through direct extension from the parotid gland. The anatomic relationship between the temporal bone and parotid gland is responsible for this tendency. The parotid gland is located in close proximity to the mastoid and tympanic portions of the temporal bone. It communicates directly with the cartilaginous EAC through the fissures of Santorini and foramen of Huschke.8 The stylomastoid foramen, carotid canal, jugular foramen, petrotympanic fissure, and eustachian tube provide avenues for intratemporal extension. In primary temporal bone carcinoma, these anatomic pathways are particularly significant as routes for extension beyond the temporal bone to the adjacent parotid tissue and soft tissue at the base of the skull base.

In rare cases of temporal bone involvement by benign tumors of the parotid gland, symptoms of a facial mass, trismus, or compression of the parapharyngeal space by tumor usually precede temporal bone involvement.9 Additionally, benign masses have a tendency to compress or remodel adjacent tissue, rather than invade it. This tendency allows for extirpation of a benign parotid neoplasm, in some cases, without requiring a formal temporal bone resection. These lesions can be removed through traditional parotidectomy techniques. Disarticulation of the mandibular condyle, resection of the EAC, or mastoidectomy may be necessary to assist with resection. Pleomorphic adenoma of the tail of the parotid gland can manifest as a subcutaneous mass of the floor of the lateral portion of the EAC. This situation is best managed with combined superficial parotidectomy with mastoidectomy and postauricular canalplasty.

Temporal bone involvement by malignancies of salivary gland origin is aggressive and involves adjacent tissue more readily. Tumors can develop insidiously and relatively asymptomatically, with 75% manifesting with a painless mass and only 6% to 13% manifesting with facial nerve palsy. Symptoms may not be present until after temporal bone invasion has occurred. Pain, dysphagia, and dysphonia can occur after direct invasion of the skull or involvement of the lower cranial nerves at the jugular foramen. Direct extension into bone, fissures, and foramina are potential routes of spread. Mass lesions of the poststyloid parapharyngeal space can traverse the carotid canal and jugular foramen, and neurotrophic tumors, such as adenoid cystic carcinoma, follow the facial nerve as an avenue toward the stylomastoid foramen. Carcinoma of the auricle, anterior scalp, or face that has spread to the intraparotid lymphatics can involve the temporal bone in a similar fashion. In a review of 27 cases of advanced and recurrent parotid neoplasms requiring temporal bone resection, Leonetti and colleagues9 found that adenocarcinoma occurred most commonly followed by adenoid cystic carcinoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

The close proximity of vital structures within and adjacent to the temporal bone requires an accurate assessment of the involved anatomy. CT and MRI are indispensable in this regard. The ability of CT to detail bony structures and the superb soft tissue contrast offered by MRI play complementary roles during the work-up. Together, CT and MRI are helpful in establishing tumor extent, the involvement of critical structures, and the best surgical plan.10

The use of high-resolution CT with fine cuts is recommended. Images with a thickness of 0.625 to 1.25 mm produce the best assessment of the skull base. Direct axial and coronal scans should be obtained. When advanced scanning technologies are available, reconstructed images provide resolution that is equivalent to the original data set. CT is essential to preoperative staging. Arriaga and colleagues11 showed that CT can “achieve 98% accuracy in predicting pathologic involvement in temporal bone resection specimens.” CT scans have limitations, however. Distinguishing mucosal inflammation from tumor and the extension of tumor without bony erosion remains difficult. In previously operated areas, positron emission tomography (PET) combined with CT has proven useful for distinguishing scar from neoplasm in identifying tumor recurrence and guiding treatment.12

A four-vessel angiogram with venous runoff should be used in cases of carotid encasement, or when disease mandates dissection of the petrous carotid. Arterial stenosis and contour irregularity at the site of the lesion suggest malignant involvement. Close inspection of the carotid canal on CT and CT angiography is useful for carotid assessment. Temporary balloon occlusion coupled with a cerebral blood flow quantification study helps to determine when carotid sacrifice would be tolerated. Quantification studies include PET, functional MRI, and xenon-CT. Xenon-CT is the best-studied modality.13 An occlusional cerebral blood flow less than 30 mL/100 g/min requires carotid bypass with prophylactic or intraoperative saphenous grafting or consideration of preoperative carotid stenting.14 Cerebral blood flow less than 30 mL/100 g/min or the development of neurologic symptoms during the test indicates a high risk of perioperative stroke. These findings either preclude the surgical option or require that prophylactic revascularization be done if surgery is performed. The venous side of imaging must not be ignored. If the torcular Herophili is not patent, permitting venous drainage from the ipsilateral sigmoid-transverse system to the opposite sigmoid-transverse-jugular system, venous infarction may occur. Specific attention should be focused on the adequacy of contralateral venous drainage.

STAGING

The American Joint Committee on Cancer states that a staging system should provide a sound basis for therapeutic planning for cancer patients by describing the survival and resultant treatment of different groups in comparable form. A lack of uniformity regarding preoperative staging and treatment plans made the study of temporal bone cancer difficult. This situation has changed with the demonstration that CT accurately predicts the degree of neoplastic involvement. The supplementation of these observations with clinical findings enabled the formation of a reliable system for staging carcinoma of the EAC.11 Attempts to modify this system have been made. Moody and coworkers15 proposed upstaging patients with preoperative facial nerve paralysis or paresis to T4 status when the primary tumor originates in the EAC. They proposed that the extension of tumor through tissue separating the facial nerve and EAC and tumor involving the horizontal segment of the nerve are ominous signs.15 Although this and other modifications to the original system by Arriaga and colleagues11 have been suggested, the original system has provided a useful framework for staging these lesions (Table 3-1), and validation of the various systems is still pending.

TABLE 3-1 Arriaga—University of Pittsburgh Tumor Lymph Node Metastasis Staging System Proposed for Squamous Cell Carcinoma of the External Auditory Canal

| T STATUS |

| T1—Tumor limited to external auditory canal without bony erosion or evidence of soft tissue extension |

| T2—Tumor with limited external auditory canal bony erosion (not full-thickness) or radiographic finding consistent with limited (<0.5 cm) soft tissue involvement |

| T3—Tumor eroding osseous external auditory canal (full-thickness) with limited (<0.5 cm) soft tissue involvement, or tumor involving middle ear or mastoid, or patients presenting with facial paralysis |

| T4—Tumor eroding cochlea, petrous apex, medial wall of middle ear, carotid canal, jugular foramen, or dura, or with extensive (>0.5 cm) soft tissue involvement |

| N STATUS |

| Involvement of lymph nodes is a poor prognostic finding and automatically places patient in advanced stage (i.e., stage III [T1, N1] or stage IV [T2, T3, and T4, N1] disease) |

| M STATUS |

| Distant metastasis indicates poor prognosis and immediately places patient in stage IV |

SURGICAL TREATMENT

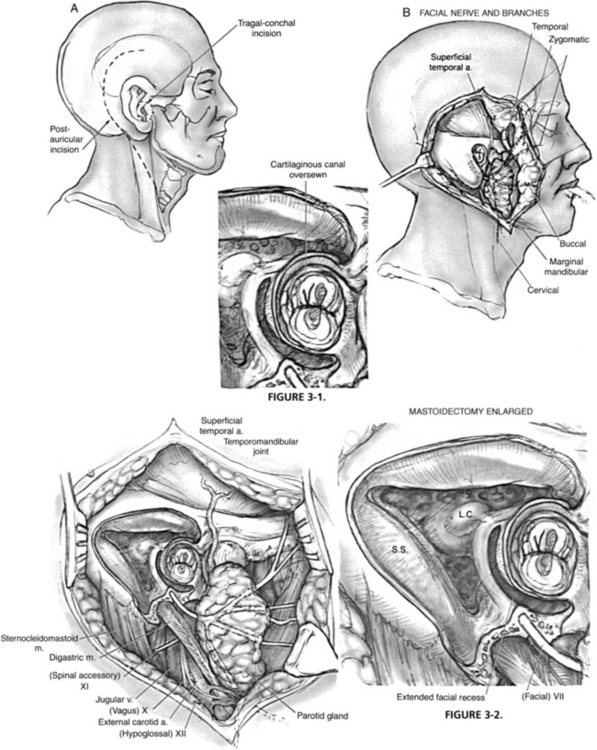

Partial temporal bone resection includes removal of the entire external auditory meatus. It is indicated for cancer of the temporal bone that is limited to the external canal. The facial nerve, stapes, and promontory provide the medial limit of resection. The incisions and soft tissue management for all temporal bone resections depend on the planned management of the pinna. If the pinna is extensively involved and is to be sacrificed, a postauricular incision combined with a preauricular incision permits excision of the pinna—usually the pinna is resected in continuity with the temporal bone resection and parotidectomy specimen. If the pinna can be preserved, a circumferential incision around the soft tissue of the ear canal is performed, and the opening is sutured closed to prevent contamination by tumor spillage during manipulation of the specimen (Fig. 3-1).

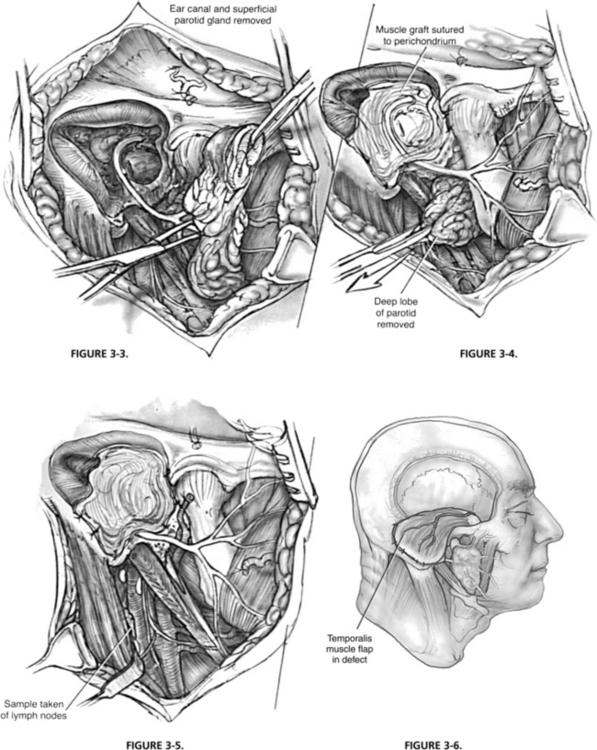

When the superior and inferior approaches to the glenoid fossa have been completed, the incudostapedial joint is separated; the tensor tympani is cut, and the ligamentous attachments of the ossicles are divided. At this point, the anterior portion of the external canal is its only remaining attachment (Figs. 3-2 and 3-3). This bone is fractured free of the carotid with gentle pressure or tapping with an osteotome. If a chisel is used, it is important to angle the instrument lateral to the carotid so that inadvertent injury of the vessel can be avoided. When the specimen has been removed, and the middle ear has been fully exposed, the eustachian tube is obliterated by filling it with muscle or fascia.

Absorbable knitted fabric (Surgicel) can be packed extraluminally to occlude the sinus. Brisk bleeding from the inferior petrosal sinus and condylar vein occurs with opening of the jugular bulb, and the surgeon should be prepared with additional Surgicel packing. Although the initial packing involves significant material, the surgeon can gradually remove most of the packing leaving only the small portions occluding the openings of the inferior petrosal sinus and condylar vein in the bulb, and limit the risks to the lower cranial nerves in the pars nervosa of the jugular bulb from excessive packing and pressure. An additional strategy to prevent bleeding from the jugular bulb is preoperative coil embolization of the openings of the inferior petrosal sinus and condylar vein.16 The final resection margins proceed along the floor of the middle fossa connecting the glenoid fossa, internal auditory canal, and posterior-superior mastoid.

When the cancer has progressed beyond the limits of a subtotal temporal bone resection, a total temporal bone resection may be indicated. This topic is addressed in more detail in Chapter 4. Total temporal bone resection is rarely performed because of the high level of morbidity and a lack of well-documented survival benefit except in specific circumstances, such as verrucous squamous carcinoma, in which the aggressiveness is entirely local and indolent. The surgery involves freeing the temporal bone at the petrous apex. Before extirpation, the intratemporal portion of the internal carotid artery must be dissected to the foramen lacerum, and the internal jugular vein must be ligated. Sacrifice or reconstruction of the internal carotid artery may be performed based on the results of preoperative testing.

RECONSTRUCTION

Partial temporal bone resections may be reconstructed with split-thickness skin grafts lining the mastoid and middle ear and sutured to the remaining soft tissue of the meatus. The graft should be placed to line the ear canal and mastoid bowl. Its medial extent can be carefully draped over the oval window or stapes remnant. Reconstruction of the ossicular chain can be done later. This reconstruction may require frequent postoperative care, however, and delayed healing can affect the timing of postoperative radiation. Vascularized temporal-parietal fascia or postauricular soft tissue (Palva flap) can be used to provide a vascularized bed for skin graft healing. Alternatively, the cavity can be obliterated with temporalis muscle or another rotational flap, such as a pectoralis major or sternocleidomastoid flap; however, this most likely would preclude reconstruction of the conductive hearing mechanism (Figs. 3-4, 3-5, and 3-6).

COMPLICATIONS

Hemorrhage is a common risk in temporal bone resection. The otologic surgeon should be very familiar with the different techniques to control unplanned venous bleeding from the sigmoid sinus, superior petrosal sinus, and jugular bulb. With the sigmoid sinus, gentle pressure with absorbable gelatin sponge (Gelfoam) or Cottonoid is usually adequate. Great care must be exercised to not allow packing to dislodge within the lumen of the sigmoid sinus, unless the jugular vein has already been ligated in the neck. The jugular bulb does not respond to the same hemostatic strategies as the sigmoid sinus because the vessel wall is much thinner. Venous bleeding can be responsible for massive blood loss, and losses of 2500 mL can be encountered. As mentioned previously, excessive bleeding most commonly occurs at the inferior petrosal sinus, but this bleeding can be controlled with proper technique. The excessive use of packing at the jugular foramen can result in injury to CN IX, X, and XI, so this should be done with caution.17

Injury to the carotid artery should be managed with direct pressure and placement of temporary clips proximal and distal to the insult. Systemic and intra-arterial heparin should be given. The injury should be repaired with 8-0 monofilament suture. If minor leaks persist after closure, topical hemostatic agents can be applied. If successful repair of the vessel cannot be achieved, the preoperative balloon occlusion test should be used to guide management. Vascular surgery and neurosurgical consultation are imperative. If there is significant carotid involvement, preoperative stent placement has been suggested to avoid vascular complications.14

If dura has been excised or violated, the resulting defect must be repaired immediately. Primary closure should be instituted whenever possible. If necessary, the dural defect should be obliterated with fat, fascia, or free tissue transfer. Postoperative leakage of cerebrospinal fluid can be managed conservatively for 7 to 10 days with appropriate measures. Bed rest, elevation of the head of the bed, stool softeners, and placement of a lumbar drain can be useful in reducing intracranial pressure.18 If the leak persists beyond this period, the wound should be explored surgically, and closure of the dural defect should be reattempted.

RADIATION

The rarity of temporal bone malignancy makes the study of treatment protocols difficult, but encouraging results have been reported. T1 lesions successfully treated with surgery alone have a 95% 5-year survival, with no benefit from the addition of radiation. Some T2 and T3 lesions treated with radiation after complete surgical removal have shown an 85% 5-year survival. The 5-year survival of patients with more advanced lesions decreases to less than 50%. Cancer requiring a total temporal bone resection carries a dismal prognosis, with a 50% 1-year survival and reports of 0% 2-year survival.5,6,19

CHEMOTHERAPY

Nakagawa and coworkers2 published data that suggest a possible role for preoperative chemoradiation therapy in the treatment of T3 and T4 squamous cell carcinoma when staged according to the Arriaga system. The radiation-enhancing effect of chemotherapy may be useful in reducing the tumor burden and improving control of the surgical margin. Nakagawa and coworkers2 showed improved survival rates for T4 lesions not involving dura, pyramidal apex, carotid canal, or lymph nodes that are as good as survival rates in patients with T3 lesions. The poor outcomes associated with the treatment of advanced temporal bone malignancy mandate further investigation into the possible role of chemotherapy as a treatment modality.

REHABILITATION OF LOWER CRANIAL NERVE DEFICITS

The impact of radiation sequelae such as xerostomia on swallowing should not be underestimated.20 Nonetheless, postoperative radiation is a crucial part of the comprehensive management of a patient with temporal bone carcinoma.

1. Kinney S.E., et al. Malignancies of the temporal bone: Limited temporal bone resection. In: Brackmann D.E., Shelton C., Arriaga M.A., et al, editors. Otologic Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1994.

2. Nakagawa T., Kumamoto Y., Natori Y., et al. Squamous cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal and middle ear: An operation combined with preoperative chemoradiotherapy and a free surgical margin. Otol Neurotol. 2006;27:242-249.

3. Moffat D., De la Cruz A., Evans P.H.R. Management of tumours of the temporal bone. In: Evans P.H.R., editor. Principles and Practice of Head and Neck Oncology. London: Martin Dunitz, 2003.

4. Brackmann D.E., Arriaga M.A. Posterior fossa skull base neoplasms. In Cummings C., Fredrickson J., Krause C., Schuller D., editors: Cummings Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 4th ed, St. Louis: Mosby, 2005.

5. Prasad S., Janecka I.P., et al. Malignancies of the temporal bone: Radical temporal bone resection. In: Brackmann D.E., Shelton C., Arriaga M.A., editors. Otologic Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1994.

6. Marsh M.M., Jenkins H.A. Temporal bone neoplasms and lateral cranial base surgery. In Cummings C., Fredrickson J., Krause C., Schuller D., editors: Cummings Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery, 4th ed, St. Louis: Mosby, 2005.

7. Peters B.R., Maddox H.E., Batsakia J.G. Pleomorphic adenoma of the middle ear and mastoid with posterior fossa extension. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988;114:676-678.

8. Prasad M., Kraus D. Acinic cell carcinoma of the parotid gland presenting as an external auditory canal mass. Head Neck. 2004;26:85-88.

9. Leonetti J.P., Smith P.G., Anand V., et al. Subtotal petrosectomy in the management of advanced parotid neoplasms. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;108:270-276.

10. Glenn L. Innovations in neuroimaging of skull base pathology. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2005;38:613-629.

11. Arriaga M., et al. Staging proposal for external auditory meatus carcinoma based on preoperative clinical examination and computed tomography findings. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1990;99:714-721.

12. Shintani S.A., Foote R.L., Lowe V.J., et al. Utilizing of PET/CT imaging performed early after surgical resection in the adjunct treatment planning from head and neck cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2008;70(2):322-329.

13. Janecka I.P., Sekhar L.N., Horton J.A. General blood flow evaluation. In: Cummings C.W., Fredrickson J., Krause C., Schuller D., editors. Otolaryngology–Head and Neck Surgery Update II. St. Louis: Mosby–Year Book; 1990:54-63.

14. Sanna M., Khrais T., Menozi R., et al. Surgical removal of jugular paraganglioma after stenting of the intratemporal internal carotid artery: A preliminary report. Laryngoscope. 2006;116:742-746.

15. Moody S.A., Hirsch B.E., Myers E.N. Squamous cell carcinoma of the external auditory canal: An evaluation of a staging system. Am J Otol. 2000;21:582-588.

16. Carrier D., Arriaga M.A., Dahlen R. Preoperative embolization of anastomosis of the jugular bulb: A new adjuvant in jugular foramen surgery. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 1997;18:1252-1256.

17. Brackmann D.E., Arriaga M.A., et al. Surgery for glomus and jugular foramen tumors. In: Brackmann D.E., Shelton C., Arriaga M.A., editors. Otologic Surgery. Philadelphia: Saunders, 1994.

18. Nuss D.W., Constantino P.D. Cerebrospinal fluid leaks: Comprehensive diagnosis and management. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;108:539.

19. Pensak M., Willging J.P. Tumors of the temporal bone. In: Jackler R., editor. Neurotology. St. Louis: Mosby, 1994.

20. Koukourakis M.I., Danieldis V. Preventing radiation induced xerostomia. Cancer Treat Rev. 2005;31:546-554.