Chapter 15

Male Genitalia and Hernias

If a man’s urine is like the urine of an ass, like beer yeast, like wine yeast or varnish, that man is sick … and through a bronze tube in the penis pour oil and beer and licorice.

From the Sushruta Samhita (ca. 3000 BCE)

General Considerations

Since the beginning of recorded history, the external genitalia and the urologic system have been of special interest to people. Kidney stones and urologic surgery were well described in antiquity. One of the earliest reported kidney stones was found in a young boy who lived about 7000 BCE.

Circumcision is one of the oldest known surgical procedures in medicine. Male circumcision has been widely practiced as a religious rite since ancient times. An initiatory rite of Judaism, circumcision is also practiced by Muslims, for whom it signifies spiritual purification. Although the origin is unknown, circumcision is often depicted on the walls of temples dating from 3000 BCE. In the Egyptian Book of the Dead, it is written, “The blood falls from the phallus of the Sun God as he starts to incise himself.” By the time of the Roman takeover of Egypt in 30 BCE, the practice of circumcision had a ritual significance, and only circumcised priests could perform certain religious rites. The Hindus regarded the penis and testicles as a symbol of the center of life and sacrificed the prepuce as a special offering to the gods.

The Bible has many urologic references. In Genesis 17 : 7, Abraham makes a covenant with God for the Jews. He is told in Genesis 17 : 14, “And the uncircumcised male who is not circumcised in the flesh of his foreskin, that soul shall be cut off from his people; he hath broken My covenant.” In Leviticus 12 : 3, the Jews were told, “And in the eighth day the flesh of his foreskin shall be circumcised.” Leviticus 15 : 2–17 deals with discharges that render a man unclean. Today, it is estimated that 1 in every 6 men worldwide is circumcised. There are more than 15 million postinfancy circumcisions a year, and thus it is one of the most common surgical procedures.

The Bible, Hindu literature, and Egyptian papyri described a disease now presumed to be gonorrhea. The Mesopotamian tablets described a variety of cures, such as this: “If a man’s penis on occasions of his pleasure hurts him, boil beer and milk and anoint him from the pubis.” Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine (1000 CE) was considered the authoritative medical text for centuries and described placing a louse in the penis to counteract a penile discharge.

Gonorrhea was probably first named by Galen in the second century CE. Gonorrhea is the Greek translation of “a flow of offspring.” Galen apparently thought that the purulent discharge was a leakage of semen. Many terms have been used to describe gonorrhea throughout the years. Perhaps the most common is clap, a name used for the past 400 years. It is thought that the term clap was derived from a specific area in Paris known for prostitution called Le Clapier.

Benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) is the most common benign neoplasm in aging men. It has been estimated that by 60 years of age, the prevalence is greater than 50%, and by 85 years of age, the prevalence approaches 90%. In addition, by 80 years of age, 1 in every 4 men requires some form of treatment for relief of symptomatic BPH. More than 300,000 surgical procedures are performed in the United States annually for BPH, most commonly a transurethral resection of the prostate.

Cancer of the genitourinary system is common. In the United States, in 2011, prostate cancer accounted for 29% of all cancer cases in men. It accounted for 11% of all cancer deaths and was the second most common cause of cancer deaths after lung and bronchus cancer (28%). In 2011, there were 240,890 new cases of prostate cancer and 33,720 deaths from the disease in the United States.

For reasons that remain unclear, the highest incidence rate for prostate cancer is in African American men and Jamaican men of African descent (54.8 per 100,000); for white persons, it is 23.7 per 100,000. The lowest incidence rate is in Asians and Pacific Islanders (10.7 per 100,000). For a 50-year-old man with a 75-year life expectancy, the lifetime risk for development of microscopic prostate cancer is 42%; the risk for development of clinically evident prostate cancer is 10%; and the risk for development of fatal prostate cancer is 3%. Genetic studies suggest that strong familial predisposition may be responsible for 5% to 10% of prostate cancers. Some recent studies have shown that a diet high in processed meat or dairy foods may be a risk factor, and obesity appears to increase the risk of aggressive prostate cancer. Approximately 95% of all prostate cancers arise from an area of the gland where it can be readily detected by rectal examination. More than 90% of all prostate cancers are discovered in the local or regional stages, for which the 5-year survival approaches 100%. During the past 25 years, the 5-year relative survival rate for all stages combined has increased from 69% to 99.6%. According to the most recent data, 10-year survival is 95% and the 15-year survival is 82%. Obesity and smoking are associated with an increased risk of dying from prostate cancer.

Cancer of the urinary bladder accounted for an additional 6% of cancer cases but only 4% of all cancer deaths in men and less than 1% in women. In 2011, there were 69,250 new cases (52,020 in men, 17,230 in women) of cancer of the urinary bladder in the United States and 14,990 deaths from the disease. Cancer of the urinary bladder is the fourth most common malignancy among men and the eighth most frequent among women. Approximately 260,000 new cases of urinary bladder cancer are diagnosed worldwide every year. The highest incidence rates for bladder cancer are found in industrialized countries such as the United States, Canada, France, Denmark, Italy, and Spain. The lowest rates are in Asia and South America, where the incidence is only approximately 30% as high as in the United States. Cigarette smoking is an established risk factor for cancer of the urinary bladder. It is estimated that approximately 50% of these cancers in men and 30% in women are linked to smoking. Occupational exposures may account for up to 25% of all urinary bladder cancers. Most of the occupationally accrued risk is attributable to exposure to a group of chemicals known as arylamines. Occupations with high exposure to arylamines include dye workers, rubber workers, leather workers, truck drivers, painters, and aluminum workers. People who live in communities with high arsenic levels in the drinking water also have an increased risk of cancer of the urinary bladder.

Although testicular cancer accounts for only 1% of all cancers in men, testicular carcinoma is the most common cancer in men in the 15- to 35-year-old age group. There were 8290 new testicular cancer cases in 2011 and 350 related deaths. Testicular cancer is four times less common in African-American men than in white men. The risk for development of testicular cancer in a man’s lifetime is approximately 1 per 500. Approximately 90% of all testicular tumors manifest as an asymptomatic testicular mass. Once these tumors are detected and treatment is begun, the cure rate can approach 90%, even when the tumor has spread beyond the testicle. Many patients have oligospermia or sperm abnormalities before therapy. Virtually all become oligospermic during chemotherapy with platinum-based agents. Many recover sperm production, however, and can father children, often without the use of cryopreserved semen. In a population-based study, 70% of patients actually fathered children. Men in whom testicular cancer has been cured have approximately a 2% to 5% cumulative risk of developing a cancer in the opposite testicle during the 25 years after initial diagnosis. The most important prognostic factor has been shown to be early detection by routine physical examination and self-examination. All men should be instructed in testicular self-examination.

There were 60,920 new cases of renal cancer in 2011. These included 92% renal cell carcinoma, 7% renal pelvis carcinoma, and 1% Wilms tumor, a childhood cancer that develops before the age of 5 years. The American Cancer Society reported 13,120 deaths from all types of renal cancer. Tobacco use is a strong risk factor for renal cancer with the largest increased risk for cancer of the renal pelvis, particularly in heavy smokers.

Erectile dysfunction (ED) is an extremely common problem. It has been estimated that more than 30 million American men have some degree of ED and that nearly a million new cases can be expected to develop annually. Studies have shown that ED affects not only a man’s physical and sexual satisfaction but also his general quality of life, with especially strong links to depression. In the Massachusetts Male Aging Study, 52% of men from 40 to 70 years of age had some degree of ED. Seventeen percent reported minimal dysfunction, 25% reported moderate dysfunction, and 10% reported complete dysfunction. This study also revealed the progressive nature of ED with increasing age. At 40 years of age, 5% of the American male population has complete ED, and at 70 years of age, 15% of the population has complete ED. Sixty-seven percent of men 70 years of age have some degree of ED. As the population continues to age, clinicians will treat more and more male patients for ED in the future.

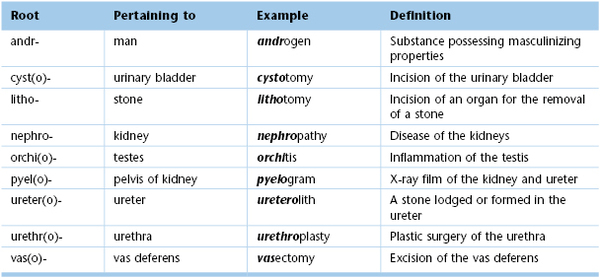

Structure and Physiologic Characteristics

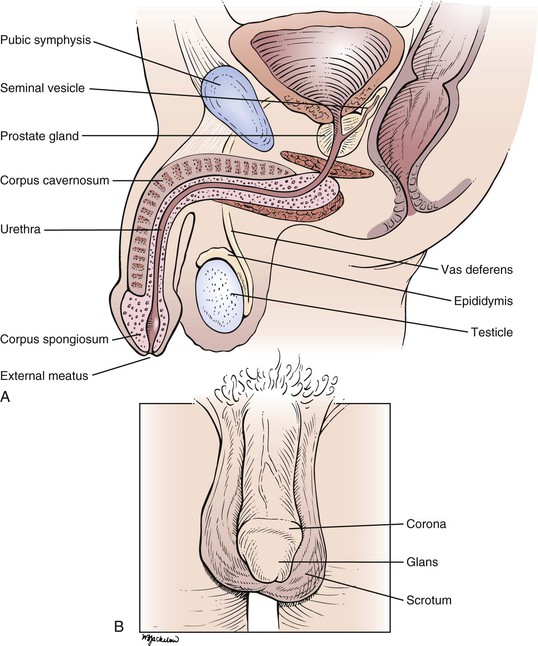

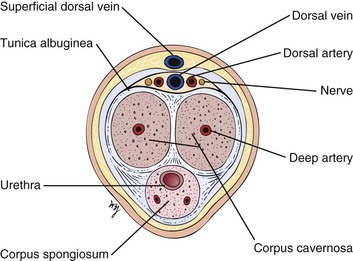

Cross-sectional and frontal views of the male genitalia are shown in Figure 15-1.

The penis is composed of three elongated, distensible structures: two paired corpora cavernosa and a single corpus spongiosum. The urethra runs through the corpus spongiosum. The penis has two surfaces, dorsal and ventral (urethral), and consists of the root, the shaft, and the head. The shaft is composed of erectile tissue that, when engorged with blood, produces a firm erection necessary for sexual intercourse. The corpora cavernosa also contain smooth muscle that contracts rhythmically during ejaculation.

On the dorsal aspect of the penis in the midline runs the dorsal vein, with an artery and a nerve on either side. The distal end of the corpus spongiosum expands to form the head, or glans penis. The glans penis covers the end of the corpora cavernosa. The glans has a prominent margin on its dorsal aspect, the corona. A slitlike opening on the tip of the glans is the external meatus of the urethra.

The skin of the penis is smooth, thin, and hairless. At the distal end of the penis, a free fold of skin called the prepuce (foreskin) covers the glans. Secreted mucus and sloughed epithelial cells called smegma collect between the prepuce and the glans, providing a lubricant during sexual intercourse. The prepuce can be retracted to expose the glans as far as the corona. During circumcision, the prepuce is removed.

The root of the penis lies deep to the scrotum, in the perineum. At the root, the corpora cavernosa diverge. Each corpus cavernosum is enveloped in a dense, fibroelastic covering called the tunica albuginea, and these tunicae fuse to form the median septum of the penis. A cross section through the penis is shown in Figure 15-2.

Figure 15–2 Cross-sectional view through the penis.

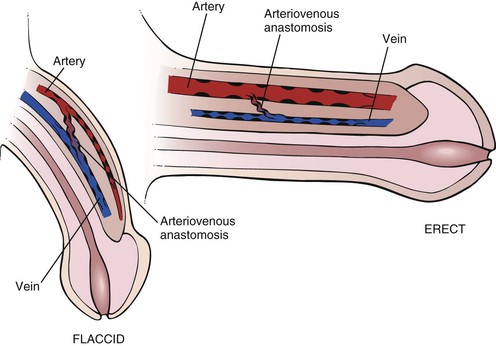

The blood supply to the penis is from the internal pudendal artery, from which the dorsal and deep arteries of the corpora cavernosa are derived. The veins drain into the dorsal vein of the penis. In the flaccid state, the venous channels and arteriovenous anastomoses are widely patent, whereas the arteries are partially constricted.

Erection is a complex hemodynamic and neurophysiologic event. In the flaccid state, the smooth muscles of the penile arteries and sinusoid spaces are contracted. The erectile state begins in the brain and requires relaxation of the smooth muscles of the penis. From the brain center, neural signals are sent to the corpora cavernosa, where synthesis and release of the neurotransmitter nitric oxide occur. Nitric oxide is the primary mediator responsible for endothelial and cavernous smooth muscle relaxation. Nitric oxide activates guanylate cyclase to produce cyclic guanosine monophosphate (GMP), which decreases intracellular calcium levels, allowing smooth muscle relaxation and an increase in arterial inflow and corporal veno-occlusion in the penis. Venous outflow is decreased because distention of the blood-filled sinusoidal spaces compresses the veins against the inner layer of the rigid tunica albuginea. In the erect state, the arteriovenous channels are closed, and the arteries are widely opened. Muscular pillars are present in the walls of the arteries, veins, and arteriovenous anastomoses, which aid in occluding the lumina. Phosphodiesterase, predominantly type V in penile tissue, catalyzes the conversion of cyclic GMP to GMP and results in detumescence. There are some new medications that selectively inhibit phosphodiesterase V. These agents enhance the effect of the nitric oxide–mediated increase in cyclic GMP levels and significantly improve erectile function and sexual function in men. The anatomy of erection is illustrated in Figure 15-3.

Figure 15–3 Anatomy of erection.

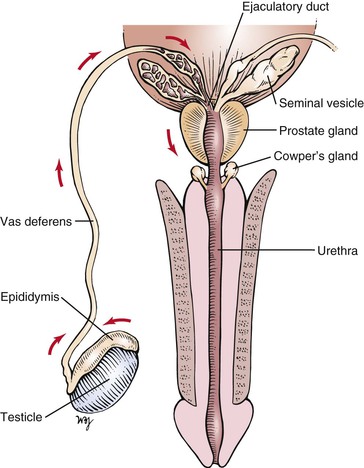

The urethra extends from the internal urinary meatus of the bladder to the external meatus of the penis. The urethra can be divided into three portions: the prostatic (posterior) portion, the membranous portion, and the cavernous (anterior) portion. The short posterior portion passes through the prostate gland. The common ejaculatory duct and several prostatic ducts enter at the distal end of this portion. The external urethral sphincter surrounds the membranous urethra, and on either side lie Cowper’s bulbourethral glands. The anterior urethra is the longest portion and passes through the corpus spongiosum. The ducts of Cowper’s glands enter the anterior urethra near its proximal end.

The scrotum is the pouch containing the testes; it is suspended externally from the perineum. The scrotum is divided into halves by the intrascrotal septum, one testis lying on each side. The wall of the scrotum contains involuntary smooth muscle and voluntary striated muscle. A major role of the scrotum is temperature regulation of the testes. The testes are maintained at approximately 2° C lower than the temperature of the peritoneal cavity, a condition necessary for spermatogenesis. The size of the scrotum is variable according to the individual and his response to ambient temperature. During exposure to cold temperatures, the scrotum is contracted and very rugate. In a warm environment, the scrotum becomes pendulous and smoother.

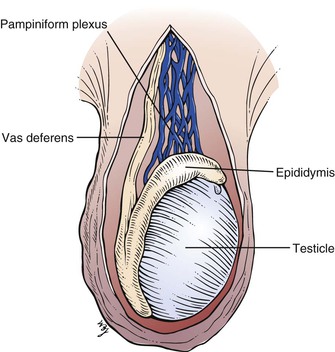

The testes, or testicles, are ovoid, smooth, and approximately 1.5 to 2 inches (3.5 to 5 cm) in length. The left testicle commonly lies lower than the right. The testes are covered with a tough fibrous coat called the tunica albuginea testis. Each testicle has a long axis directed slightly anteriorly and upward and contains long, microscopic, convoluted seminiferous tubules that produce sperm. The tubules end in the epididymis, which is comma-shaped and located on the posterior border of the testis. It consists of a head that is swollen and overhangs the upper pole of the testicle. The inferior portion, or tail, of the epididymis continues into the vas deferens. The testicular artery enters the testicle in its posterior midportion. The veins draining the testicle form a dense network called the pampiniform plexus, which drains into the testicular vein. The right testicular vein drains directly into the inferior vena cava, whereas the left drains into the left renal vein. The lymphatic drainage of the testes is to the preaortic and precaval nodes, not to the inguinal nodes. This is important to recognize because the testes are embryologically intra-abdominal organs, and neoplasms and inflammations of the testis produce adenopathy of these nodal chains. In general, inguinal adenopathy is rare.

The relationship of the testicle and epididymis is illustrated in Figure 15-4.

Figure 15–4 Anatomy of the testicle and epididymis.

The vas deferens is a cordlike structure, easily felt in the scrotum. The vas deferens, testicular arteries, and veins form the spermatic cord, which enters the inguinal canal. The vas deferens passes through the internal ring and, after a convoluted course, reaches the fundus of the bladder. It passes between the rectum and the bladder and approaches the vas deferens of the opposite side near the seminal vesicles. Near the base of the prostate, the vas deferens joins with the duct of the corresponding seminal vesicle to form the ejaculatory duct, which passes through the prostate gland to enter the posterior urethra.

The prostate gland is approximately the size of two almonds, or approximately 1.5 inches (3.5 cm) long by 1.2 inches (3 cm) wide. Traversing the gland in the midline is the posterior urethra. On either side is an ejaculatory duct. The prostate is commonly divided into five lobes. The posterior lobe is clinically important because prostate carcinoma frequently affects this lobe. In the presence of cancer, the midline groove between the two lateral lobes may be obliterated. The middle and lateral lobes are above the ejaculatory ducts and are typically involved in benign hypertrophy. The anterior lobe is of little clinical importance.

The sources and direction of seminal fluid flow in the male genitalia are illustrated in Figure 15-5.

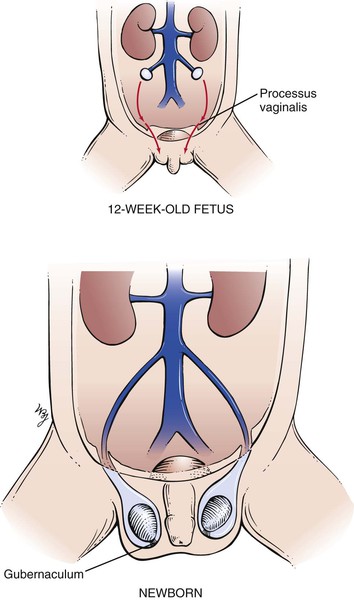

Figure 15–5 Sources and direction of seminal fluid flow.

The descent of the testes is important to review at this time. In the normal full-term male newborn, both testes are in the scrotum at birth. The testes descend to this position just before birth. At approximately the twelfth week of gestation, the gubernaculum develops in the inguinal fold and grows through the body wall to an area that will ultimately lie in the scrotum. This tract marks the location of the future inguinal canal. A dimple called the processus vaginalis forms in the peritoneum and follows the course of the gubernaculum. By the seventh month of gestation, the processus vaginalis has reached the aponeurosis of the external oblique muscle. Each testis then begins its descent from the abdominal cavity through the internal ring to lie in the abdominal wall. During the eighth month, the testes descend along the inguinal canal; at birth, they are in the scrotum. At birth, the gubernaculum is barely distinguishable, and the processus vaginalis becomes obliterated within the spermatic cord. In approximately 5% of male infants, there is imperfect descent of the testis (cryptorchidism). The descent of the testes is illustrated in Figure 15-6.

Figure 15–6 Descent of the testes.

The genital development stages for boys are illustrated in Figure 21-42 (and discussed in Chapter 21, The Pediatric Patient).

Review of Specific Symptoms

The most common symptoms of male genitourinary disease are as follows:

Pain

Sudden distention of the ureter, renal pelvis, or bladder may cause flank pain. Any patient with flank pain should be asked the following questions:

“Where did the pain begin? Can you point to the area?”

“Do you feel the pain in any other area of your body?”

“Did the pain start suddenly?”

“Have you ever had this type of pain before?”

“What seems to make the pain worse? Less?”

Gradual enlargement of an organ is usually painless. An aching pain in the costovertebral angle may be related to sudden distention of the renal capsule, which results from acute pyelonephritis or obstructive hydronephrosis. The spasmodic, colicky pain from upper ureteral dilatation may cause referred pain to the testis on the same side. Lower ureteral dilatation may cause pain referred to the scrotum. The pain of ureteral distention is severe, and the patient is restless and uncomfortable in any position. Bladder distention causes lower abdominal fullness and suprapubic pain, with an intense desire to urinate. Pain in the groin may result from pathologic processes in the spermatic cord, testicle, or prostate gland; from lymphadenitis of any cause; from hernia; from herpes zoster; or from a disorder that is neurologic in origin.

Testicular pain can result from nearly any disease of the testis or epididymis. Such diseases include epididymitis, orchitis, hydrocele, spermatic cord torsion, and tumor. Referred pain from the ipsilateral ureter must always be considered. Priapism is a painful, persistent erection of the penis that is not a result of sexual excitation. The sustained erection results from thrombosis of veins in the corpora cavernosa. This occurs in patients with sickle cell anemia or leukemia. The exact mechanism is unknown, but it appears to result from a blockage of venous drainage from the penis while the arteries remain patent. Chronic priapism often results in organic ED.

Dysuria

Pain on urination, called dysuria, is frequently described as “burning.” Dysuria is evidence of inflammation of the lower urinary tract. The patient may describe discomfort in the penis or in the suprapubic area. Dysuria also implies difficulty in urination. This may result from external meatal stenosis or from a urethral stricture. Painful urination is usually associated with urinary frequency and urgency. When the patient describes pain or difficulty in urination, ask the following questions:

“How long have you noticed a burning sensation on urination?”

“How often do you urinate each day?”

“How does your urination feel different?”

“Do you have a discharge from your penis?”

“Does the urine seem to have gas bubbles in it?”

Fecaluria is the presence of fecal material in the urine and is rare. The passage of feculent-smelling material results from either an intestinovesicular fistula or an urethrorectal fistula. These fistulas occur as a consequence of ulceration from the bowel to the urinary tract. Diverticulitis, carcinoma, and Crohn’s disease are frequent causes.

Pus in the urine, or pyuria, is the body’s response to inflammation of the urinary tract. Bacteria are the most common cause of inflammation resulting in pyuria, although pyuria is also seen in patients with neoplasms and kidney stones. Cystitis and prostatitis are common causes of pyuria.

Changes in Urine Flow

Changes in urine flow include frequency and incontinence. Urinary frequency is the most common symptom of the genitourologic system. Frequency is defined as passing urine more often than normal. Nocturia is urinary frequency at night. There are several causes of frequency: decreased bladder size, bladder wall irritation, and increased urine volume. If an obstructed bladder cannot be completely emptied at each voiding, its effective capacity is diminished. The following questions, in addition to the ones pertaining to dysuria, should be asked to help define the problem.

“Do you find that you must wake up at night to urinate?”

“Can you estimate the amount of urine passed each time you urinate?”

“Do you have sudden urges to urinate?”

“Have you found that despite an urge to urinate, you cannot start the stream?”

“Has there been a change in the caliber of the stream?”

“Have you found that you must wait longer for the stream to start?”

“Do you have the sensation that after urination has stopped, you still have to urinate?”

Prostatic hyperplasia is the most common cause of reduced usable bladder capacity in men. Symptoms include frequency of urination, nocturia, urgency, weak stream, intermittent stream, and a sensation of incomplete emptying. Long-standing prostatic hypertrophy can lead to a complete inability to urinate, necessitating catheterization (a condition known as urinary retention), or can lead to urinary tract infections or to bladder stones. Most bladder diseases, such as cystitis, cause frequency as a result of irritation of the bladder mucosa. Polyuria, or voiding large amounts of urine, is usually accompanied by excessive thirst, or polydipsia. Diabetes mellitus and diabetes insipidus are common causes of polydipsia.

Urinary incontinence is the inability to retain urine voluntarily. The urge to urinate may be so intense that incontinence may result. In addition to the questions regarding dysuria and frequency, ask the following:

“Do you involuntarily lose small amounts of urine?”

“Do you lose your urine constantly?”

“Do you lose your urine when lifting heavy objects? Laughing? Coughing? Bending over?”

In patients with chronically distended bladders, as in those with prostatic hypertrophy, there is always a large amount of residual urine. The pressure within the bladder is constantly elevated. A slight increase in intra-abdominal pressure raises the intravesicular pressure sufficiently to overcome bladder neck resistance, and urine escapes. Leakage may be steady or intermittent. This type of incontinence is overflow incontinence. Stress incontinence is leakage that occurs only when the patient strains. The primary defect is a loss of muscular support in the urethrovesicular region. Residual urine is insignificant. Any increase in intra-abdominal pressure causes leakage. This type of incontinence is more common in women and is discussed in Chapter 16, Female Genitalia.

Polyuria is the production of increased amounts of urine, frequently greater than 2 to 3 L/day. The normal daily urine output varies from 1 to 2 L/day. The most important diseases to differentiate are diabetes mellitus, diabetes insipidus, and psychologic diabetes insipidus. Ask the following questions:

“How long have you been passing large amounts of urine?”

“How often do you have to urinate at night?”

“Is there any variability in the urine flow from day to day?”

“Do you have excessive thirst?”

“Do you prefer water or other fluids?”

“What happens if you don’t drink? Will you still have to urinate?”

Patients with diabetes mellitus have a high osmotic load and have polyuria. Increased appetite is also common. Diabetes insipidus is caused by a vasopressin deficiency related to a lesion in the hypothalamus or pituitary gland. In these patients, the urine cannot become concentrated despite a rise in plasma osmolality. Patients with psychogenic diabetes insipidus, which is more common, have polyuria related to compulsive drinking of water. It is seen in patients with psychologic problems. The onset of polyuria is abrupt in patients with psychogenic diabetes insipidus, and they have no preference for the type of fluid they drink. In contrast, patients with true diabetes insipidus prefer water. Because true diabetes insipidus is related to intracranial lesions, it is not surprising that affected individuals suffer from headaches and visual disturbances, especially visual field abnormalities.

Red Urine

Red urine is often indicative of hematuria, or blood in the urine. However, there are many causes of red urine, and it should not automatically be assumed that red urine indicates bleeding. Vegetable dyes, drugs such as phenazopyridine (Pyridium®), and excessive ingestion of beets can cause red urine. When it is determined that the urine is red as a result of the presence of blood, the hematuria is termed gross hematuria. Hematuria may be the first symptom of serious disease of the urinary tract. Ask the following questions of any patient with the symptom of red urine:

“How long have you noticed red urine?”

“Have you had red urine previously?”

“Have you noticed clots of blood in the urine?”

“Did you have an upper respiratory infection or a sore throat a few weeks ago?”

“Are you aware of any bleeding problems?”

Individuals who participate in strenuous activities may traumatize blood cells as these cells travel through the small vessels in the feet. A condition called march hemoglobinuria may result, causing intravascular hemolysis and hemoglobinuria. The temporal relationship of blood in the urine is an important factor. Blood only at the beginning, or initial hematuria, usually has a source in the urethra. Blood only at the end of urination, or terminal hematuria, indicates a disorder at the bladder neck or the posterior urethra. Blood evenly distributed throughout urination is total hematuria and implies disease above the prostate gland or a massive hemorrhage at any level. Blood staining of undergarments without blood in the urine indicates pathologic processes in the external urethral meatus. Weight loss and hematuria are seen in renal cell carcinoma. Red urine that occurs 10 to 14 days after an upper respiratory infection may indicate acute glomerulonephritis.

Penile Discharge

Discharge from the penis is a continuous or intermittent flow of fluid from the urethra. Ask the patient whether he has ever had a discharge and, if he has, whether it was bloody or purulent. Bloody penile discharges are associated with ulcerations, neoplasms, or urethritis. Purulent discharges are thick and yellowish-green and may be associated with gonococcal urethritis or chronic prostatitis. Determine when the discharge was first noted. Figure 15-7 shows a purulent penile discharge in a man with gonococcal urethritis. Gonorrhea is caused by Neisseria gonorrhoeae. After exposure, approximately 25% of men and more than 50% of women contract the disease. In men, the acute symptoms of dysuria and a purulent urethral discharge begin 2 to 10 days after exposure. In women, a vaginal discharge and dysuria develop days to weeks after exposure; however, in up to 50% of women, the infection may be asymptomatic.

Figure 15–7 Purulent penile discharge of gonorrhea.

Tactful direct questioning about any history of or exposure to sexually transmitted diseases is essential. The interviewer should determine the patient’s sexual orientation1 and the type of sexual exposure—oral, vaginal, or anal—because this information can help determine the types of bacteriologic cultures necessary. It is appropriate to ask whether the patient has more than one sexual partner and whether the partner or partners have any known illnesses. The sexual history questions suggested in Chapter 1, The Interviewer’s Questions, may be helpful.

Penile Lesions

A history of lesions on the penis should alert the examiner to the possibility of venereal disease. The differential diagnosis ranges from benign conditions to those that currently have no cure. It is important to take a thorough history, focusing on recent sexual exposures, recent travels, hygienic habits, whether the lesion is pruritic or painful, and the possible preexistence of other skin disorders. Ask the patient whether he has had gonorrhea, syphilis, herpes, trichomoniasis, venereal warts, or other sexually transmitted diseases.

Genital Rashes

Male genital rashes are very common. They may be confusing to identify and are often difficult to treat. Some rashes may occur exclusively on the genitalia; others, which are typically found on other parts of the body, have an atypical appearance when present on the genitalia. The skin over the genitalia is thin and moist, so typical dry scaliness may not be present.

The most common inflammatory reaction affecting the male genitalia is psoriasis. The patient develops bright red, well-defined, scaling plaques. Often the entire scrotum, inguinal folds, and penis are involved. The penis is a common location for psoriasis and, in some cases, it is the sole area of involvement. Psoriatic lesions on the penis are typically red, scaly, papules or raised plaques on the glans and shaft, with the exception of uncircumcised men who often lack the scale when lesions are located on the glans. Psoriatic patches on other body parts usually facilitate the diagnosis. Supportive findings include red scaly plaques on the elbows, knees (see Fig. 5-53), gluteal cleft (see Fig. 5-54), scalp (see Fig. 5-56) and periumbilicus, as well as pitting of the nail plates (see Fig. 5-14). Figure 15-8 shows psoriasis of the penis.

Figure 15–8 Psoriasis.

Another form of genital rash is contact dermatitis. It may develop from soaps or disinfectants. Irritants used for facial actinic keratoses may inadvertently be transferred to the genitalia. Itching is a major symptom.

Fixed drug eruptions are unique reactions that appear in the same area of the body each time the responsible drug is given. Fixed drug reactions manifest as a sudden onset of multiple, well-defined, macular, eczematous, bullous patches. When the genitalia are involved, these eruptions typically occur on the distal penis and glans and may be very painful. Drugs known to cause these eruptions include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, sulfonamides, and laxatives containing phenolphthalein, tetracycline, and barbiturates. Figure 15-9 shows a fixed drug reaction. More than 500 medications have been implicated in fixed drug reactions; therefore, the examiner should take a careful medication history.

Figure 15–9 Fixed drug reaction.

Lichen planus is an inflammatory disorder characterized by violaceous, flat, shiny papules ranging from 0.75 to 3 inches (2 to 8 mm) in diameter that are faintly erythematous to violet in color. The glans penis is frequently involved. Typical penile lichen planus is asymptomatic and commonly resolves with residual hyperpigmentation. An oral examination may also reveal the classic serpiginous white streaks on the buccal mucosa (see Fig. 9-15). Figure 15-10 shows lichen planus of the penis.

Figure 15–10 Lichen planus.

Scrotal Enlargement

It is not uncommon for a man to complain of enlargement of his scrotum, but it is often difficult for him to determine which anatomic structures in the scrotum are enlarged. Ask these questions:

“When did you first notice the enlargement?”

“Have you sustained any injury to your groin?”

“Does the enlargement change in size?”

Swellings in the scrotum can be related to testicular or epididymal enlargement, a hernia, a varicocele, a spermatocele, or a hydrocele. Testicular enlargement can result from inflammation or tumor. Most of the time, enlargement is unilateral. Painful scrotal enlargement can result from acute inflammation of the epididymis or testis, torsion of the spermatic cord, or a strangulated hernia. Varicoceles are often a cause of decreased male fertility.

Groin Mass or Swelling

If a patient describes a mass in the groin, ask the following questions:

The most common cause of swelling in the groin is a hernia. Hernias are reduced in size after the patient has been lying down. Adenopathy from any infection of the external genitalia may produce inguinal swelling. Carcinoma of the testis produces inguinal node enlargement only if the scrotal skin is involved.

Erectile Dysfunction

ED, or impotence, is defined as the persistent inability to achieve or maintain a penile erection sufficient for satisfactory sexual performance. The typical patient is at least 50 years old, is usually married or in a long-term monogamous relationship, and has had a year or more of gradually progressive ED. Often he is otherwise in good mental and physical health. Because penile erection is a neurovascular phenomenon, however, there are a number of neurologic and vascular conditions that can lead to ED. Vascular disease such as atherosclerotic stenosis or occlusion of the cavernosal arteries, or vascular problems secondary to smoking, can cause ED. Antihypertensives, antidepressants, antiandrogens, histamine type 2 receptor blockers, and recreational drugs are commonly associated with ED. Diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and alcohol use are risk factors in ED. ED frequently provides insight into the patient’s emotional problems.

A delicate approach must be taken. It is necessary to use tact and appropriate language that will be understood by the patient. Explaining that ED is a common problem often sets the tone. Deep-seated problems necessitate careful questioning. The interviewer may discover latent homosexuality; guilt and taboos experienced early in life may have left a lasting impression, affecting sexual performance. It is most important to classify the origin of the ED, because there are specific therapies for different causes.

Start by asking some of the following questions:

“Are you satisfied with your sexual function?” If not, “What are the reasons?”

“What is your relationship status? Is it a happy one?”

“Is your partner satisfied with your sexual function?” If not, “What are the reasons?”

“When was the last time you had a satisfactory erection?”

“Over the last 4 weeks, how would you rate your confidence that you could get and keep an erection?”

A careful history is the most essential component in the evaluation of ED. Key and direct questions are important:

“How much do or did you enjoy sexual intercourse?”

“When you have sexual stimulation or intercourse, how often do you ejaculate?”

“How easily can you reach an orgasm (climax)?”

“How strong is your sex drive?”

Some other questions may help determine the cause of ED. Psychogenic causes for ED should be suspected in men who have a history of unusual anxiety, stress, or sexual abuse or in those with ethnic, cultural, sexual, or religious inhibitions. ED is often psychogenic in men younger than 40 years. Ask the following questions:

“Do you have early morning erections or nighttime emissions?”

An affirmative answer to any of these questions reassures the interviewer that the ED is probably psychologic in origin. Letting the patient discuss his problems may allow him to vent some of his anxieties, but the patient’s confidence must first be secured by guaranteeing confidentiality. The interviewer must also resolve his or her own sexual anxieties to have a confident and straightforward discussion. An open dialogue about the anxieties surrounding sexual intercourse may be productive. The interviewer must be careful not to impose his or her own moral standards on the patient, however. Improving communication between partners is also helpful.

Infertility

Infertility is the inability to conceive or to cause pregnancy. Infertility is a common problem found in as many as 10% of all marriages. A couple is said to be infertile when after 1 year of normal intercourse without the use of contraceptives, pregnancy does not occur. It has been estimated that almost 30% of all infertility is attributable to a male factor. Any patient with a history of infertility should be questioned regarding a history of mumps, testicular injury, venereal disease, history of diabetes, history of a varicocele (see Fig. 15-27), exposure to radiation, or any urologic surgical procedure. Diabetic men may be infertile because of retrograde ejaculation, or ejaculation into the urinary bladder. Determine the frequency of sexual intercourse and any difficulty in achieving or maintaining an erection. Document a careful history of general work habits, medications taken, alcohol consumption, and sleeping habits.

Impact of Erectile Dysfunction on the Man

ED is the inability of a man to achieve or maintain an erection sufficient to accomplish coitus. ED may be either erectile or ejaculatory. This inability may also be partial or complete. Men may complain of difficulty in achieving or maintaining an erection or of premature ejaculation. The prevalence of some degree of ED ranges from 20% to 30% of the married population. As a man ages, there is a natural loss of both libido and potency. In general, this does not occur before 50 years of age. Some men remain sexually vigorous well into old age. If a patient suffering from ED has occasional erections or can achieve orgasm during masturbation, he may have a primarily emotional problem. In almost 90% of patients complaining of ED, the inadequacy is found to be caused by emotional rather than anatomic factors.

Hearing about a friend’s sexual activities, especially if they are exaggerated, can deflate a patient’s ego and heighten his sense of inadequacy. The cultural environment of the patient must set the standard for adequacy. It is almost impossible to compare Western and Eastern cultural patterns. In 1948, Alfred Kinsey and his colleagues obtained factual data on Anglo-American sexual patterns. The frequency of sexual intercourse varied from 1 to 4 times per week. The period of maximum sexual activity was from 20 to 30 years of age. It was shown that there were marked variations among individuals as well as among socioeconomic groups. The lower the socioeconomic group, the more frequent the sexual encounters.

Boredom, anxiety, peer pressure, aging, deterioration of the stereotypical male role, and female “aggressiveness” are factors contributing to psychogenic ED. Diabetes mellitus is one of the more common causes of organic ED. Patients with multiple sclerosis, spinal cord tumors, degenerative diseases of the spinal cord, and local injuries suffer from a gradual loss of potency. Certain medications can cause ED: beta-blockers, carbonic anhydrase inhibitors, and antihypertensive agents, for example.

Guilt, anxiety, and hypochondriasis are common in men with psychogenic ED. Sexual indifference in a woman may make the man feel more insecure in his own marital adjustment, worsening his ED. The man’s self-image may be poor. It is common for a man with marginal difficulties to worry incessantly about his next attempt at coitus. His fear of failure generates enormous anxiety, which reinforces his inadequacy, and a vicious circle is begun. Each failure worsens the next attempt. If the act of coitus is not satisfactory to the patient or his partner, embarrassment and guilt develop.

Some men may be able to maintain erections but have difficulty in ejaculation. They may become physically exhausted and have to stop intercourse before ejaculating. The ejaculatory ducts may become so inflamed or even ulcerated that if ejaculation does occur, blood is present in the semen. This produces further anxiety and emotional upset that aggravate the situation.

Regardless of the cause, ED has vast implications. The man may feel emasculated and develop an inferiority complex. Anger and depression are common. If the patient’s ED is associated with an anatomic defect, there may be additional changes in his self-image related to the physical disease. If sexual problems are not resolved, personality changes may develop in the patient. Fear of losing his sexual partner can interfere with his work. Sleep and rest may be disturbed. If sexual maladjustment continues, neurotic complaints may ensue. Without proper guidance, the man may experience complete ED, and suicidal tendencies may develop.

Physical Examination

The only equipment necessary for the examination of the male genitalia is disposable latex gloves. Although wearing protective gloves may decrease the examiner’s sensitivity, disposable latex gloves should always be worn.

Many students are concerned about the possibility that a patient will have an erection during the examination. Although this is possible, it is rare for a man to become sexually excited because he is usually somewhat uncomfortable under these circumstances. If the examination is performed in an objective manner, it should not be a source of stimulation to the patient. If the man does develop an erection, do not proceed with the examination.

Examination of the male genitalia is performed with the patient first lying down and then standing. This postural change is important, because hernias or scrotal masses may not be apparent in the lying-down position.

The examination of the male genitalia consists of the following:

• Inspection and palpation with the patient lying down

Inspection and Palpation with the Patient Lying Down

Inspect the Skin and Hair

While the patient is lying down, the skin in the groin should be inspected for the presence of a superficial fungal infection, excoriations, and other rashes. Excoriations may indicate a scabies infection.

Observe the distribution of hair. Inspect the pubic hair for the presence of crab lice or nits (egg cases) attached to the hair. Are any burrows of scabies present?

Inspect the Penis and Scrotum

In the examination of the penis and scrotum, note the following:

Figure 15-11 shows ectopic sebaceous glands on the shaft of the penis. The glands appear as pinhead-sized, whitish-yellow papules. These are commonly seen in normal men on the corona, the inner foreskin, and the shaft of the penis. Their appearance is very similar to Fordyce’s spots of the oral mucosa (see Fig. 9-18). Ectopic sebaceous glands also may be found in normal women on the labia minora and labia majora (see Fig. 16-13).

Figure 15–11 Ectopic sebaceous glands on the penis.

Pearly penile papules are very common around the coronal sulcus and have no racial predilection. They are thought to be embryonic remnants of a copulative prehensile organ. These fine papules are small, asymptomatic lesions that develop after puberty in 10% to 15% of men. They are skin colored, filiform in shape, and arranged in rows at the junction of the glans penis and sulcus coronarius; they are more common in uncircumcised men. They should not be confused with condylomata acuminata. Figure 15-12 shows pearly penile papules.

Figure 15–12 Pearly penile papules.

Figure 15-13 shows the penis of a patient with the chancre of primary syphilis. Although the typical syphilitic chancre is described as nontender, approximately 30% of patients with primary syphilis describe some pain or tenderness. Usually only a single lesion is present. The edge of the chancre is usually indurated. Moderate nontender inguinal adenopathy was present in this patient.

Figure 15–13 Chancre of primary syphilis.

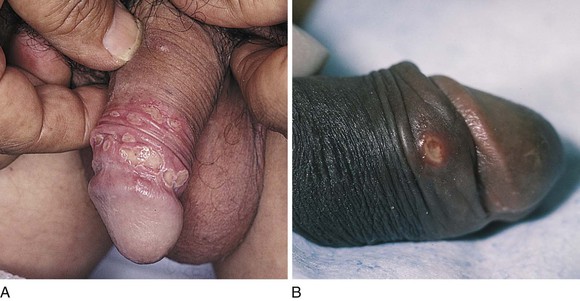

Figure 15-14 shows chancroid in two patients. In contrast to the chancre of syphilis, the ulceration of chancroid is extremely painful. The ulceration has a purulent, grayish surface that becomes granulating. Characteristically, the base of the ulcer and its vicinity are not infiltrated. There is usually moderate tender adenopathy associated with the genital lesions. Another important difference between the ulceration of chancroid and the chancre of syphilis is the frequent presence of multiple lesions in the former, as shown in Figure 15-14A. The patient in Figure 15-14B had a similar lesion on the other side of his penis.

Figure 15–14 Chancroid. A, Note the multiple lesions. B, This patient had another lesion on the other side of his penis.

Venereal warts, or condylomata acuminata, may be found near the meatus, on the glans, in the perineum, at the anus, and on the shaft of the penis. Condylomata acuminata are the characteristic lesions of human papillomavirus (HPV) infection. Typically, these papules have a verrucous surface resembling cauliflower. They are highly contagious, with transmission occurring in 30% to 60% of patients after a single exposure. Figure 15-15 shows a patient with condylomata acuminata on the shaft of his penis (see also Fig. 15-40).

Figure 15–15 Condylomata acuminata of the shaft of the penis.

Are there any papules on the penis or scrotum? Figure 15-16 shows the classic genital papular lesions in a patient with scabies.2

Figure 15–16 Scabies in the groin and on the penis.

Balanitis is inflammation of the glans penis. It is most often caused by Candida infection and is found mostly in uncircumcised men. The warmth and moisture in this area facilitate the growth of the yeast organisms. The infection begins as flat erythema on the inner side of the foreskin and glans. Pustules develop that break open and leave a moist, bright red, eroded surface. If the infection involves the glans and foreskin, the term balanoposthitis is used. Figure 15-17 shows Candida balanitis. Notice the erosions on the distal shaft and glans penis. The foreskin has been retracted.

Figure 15–17 Candida balanitis.

The scrotum is inspected for any sores or rashes. Pinpoint, dark red, slightly raised, telangiectatic lesions on the scrotum are common in individuals older than 50 years. They are angiokeratomas and are benign. Fabry’s disease, which is a rare, sex-linked inborn error of glycosphingolipid metabolism, is characterized by pain, fever, and diffuse angiokeratomas in a “bathing suit” distribution, especially around the umbilicus and scrotum. The scrotum of a 15-year-old patient with Fabry’s disease and multiple angiokeratomas is shown in Figure 15-18.

Figure 15–18 Angiokeratomas in a patient with Fabry’s disease.

The patient in Figure 15-19 has acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) and Kaposi’s sarcoma. Notice the marked penile and scrotal edema, as well as the lesions of Kaposi’s sarcoma on his thighs and scrotum.

Inspect the Perineum

The examiner elevates the patient’s scrotum to inspect the perineum carefully for any inflammation, ulceration, warts, abscesses, or other lesions.

Inspect for Groin Masses

Ask the patient to cough or strain while you inspect the groin. A sudden bulge may indicate an inguinal or femoral hernia.

Inspection and Palpation with the Patient Standing

Ask the patient to stand while you sit in front of him.

Inspect the Penis

If the patient is not circumcised, the foreskin should be retracted. Some examiners ask the patient to retract it himself; others prefer to determine the tightness of the foreskin. The cheesy, white material under the foreskin is smegma and is normal.

The glans is inspected for ulcers, warts, nodules, scars, and signs of inflammation.

Inspect the External Meatus

The examiner should note the position of the external urethral meatus. It should be central on the glans. To inspect the meatus, the examiner places his or her hands on either side of the glans penis and opens the meatus. The technique for examining the meatus is demonstrated in Figure 15-20.

The meatus should be observed for any discharge, warts, and stenosis. Figure 15-21 shows a patient with meatal condylomata acuminata.

Figure 15–21 Condylomata acuminata of the urethral meatus.

On occasion, the urethral meatus opens on the ventral surface of the penis; this birth defect is called hypospadias. Instead of opening at the tip of the glans penis, a hypospadiac urethra opens anywhere along the urethral groove running from the tip of the penis along the ventral aspect of the shaft to the junction of the penis with the scrotum or perineum. Mild hypospadias most often occurs as an isolated birth defect without detectable abnormality of the remainder of the reproductive or endocrine system. However, a minority of infants, especially those with more severe degrees of hypospadias, will have additional structural anomalies of the genitourinary tract. A less common birth defect is epispadias, in which the meatus is located on the dorsal surface of the penis.

Palpate the Penis and Urethra

Palpate the shaft from the glans to the base of the penis. The presence of scars, ulcers, nodules, induration, and signs of inflammation must be noted. To palpate the corpora cavernosa, hold the penis between the fingers of both your hands and use your index fingers to note any induration. Figure 15-22 illustrates the method of palpation of the shaft of the penis.

Figure 15–22 Technique for palpation of the penis.

The presence of nontender induration or fibrotic areas under the skin of the shaft is suggestive of Peyronie’s disease. Patients with this condition may also complain of penile deviation during erection. The erect penis has a deviation in the long axis, making sexual intercourse difficult or impossible. The patient or his partner may also complain of pain during intercourse. The site of predilection is the dorsal aspect of the penis, especially in the middle or proximal third. Figure 15-23 shows the erect penis of a patient with Peyronie’s disease.

Figure 15–23 Peyronie’s disease.

The urethra should be palpated from the external meatus through the corpus spongiosum to its base. To palpate the base of the urethra, the examiner elevates the penis with the left hand while the right index finger invaginates the scrotum in the midline and palpates deep to the base of the corpus spongiosum. The pad of the examiner’s right index finger should palpate the entire corpus spongiosum from the meatus to its base. This technique is demonstrated in Figure 15-24. If a discharge is present, “milking the urethra” may allow a drop to be placed on a glass slide for microscopic evaluation.

Figure 15–24 Technique for palpation of the base of the urethra.

The foreskin, if retracted, should be replaced. Paraphimosis is a condition in which the foreskin can be retracted but cannot be replaced and becomes caught behind the corona.

Inspect the Scrotum

The scrotum is now reevaluated while the patient is standing. Observe the contour and contents of the scrotum. Two testicles should be present. Normally the left testicle is lower than the right. The presence of any fullness not seen while the patient was lying down should be noted.

Palpate the Testes

Each testis is palpated separately. Use both hands to grasp the patient’s testicle gently. While your left hand holds the superior and inferior poles of the testicle, your right hand palpates the anterior and posterior surfaces. The technique for palpation of the testicle is demonstrated in Figure 15-25.

Figure 15–25 Technique for palpation of the testicle.

Note the size, shape, and consistency of each testicle. No tenderness or nodularity should be present. Normal testicles have a firm, rubbery consistency. The size and consistency of one testicle are compared with those of the other. Does one testicle feel heavier than the other? If a mass is present, can the examining finger palpate above the mass within the scrotum? Because inguinal hernias arise from the abdominal cavity, the examining finger is unable to get above such a mass. In contrast, the examining finger can frequently get above a mass that arises from within the scrotum.

Palpate the Epididymis and Vas Deferens

Next, locate and palpate the epididymis on the posterior aspect of the testicle. The head and tail should be carefully palpated for tenderness, nodularity, and masses.

The spermatic cord is palpated from the epididymis up to the external abdominal ring. The patient is asked to elevate his penis gently. If the penis is elevated too much, the scrotal skin is reduced, and the examination is more difficult. Hold the scrotum in the midline by placing both your thumbs in front of and both your index fingers on the perineal side of the patient’s scrotum. Using both hands, simultaneously palpate both spermatic cords between your thumbs and index fingers as you pull your fingers laterally over the scrotal surface. The most prominent structures in the spermatic cord are the vasa deferens. The vasa are firm cords approximately 0.08 to 0.15 inches (2 to 4 mm) in diameter and feel like partially cooked spaghetti. The sizes are compared, and tenderness or beading is noted. Absence of the vas deferens on one side is often associated with absence of the kidney on the same side. The technique of spermatic cord palpation is demonstrated in Figure 15-26.

Figure 15–26 Technique for palpation of the spermatic cord.

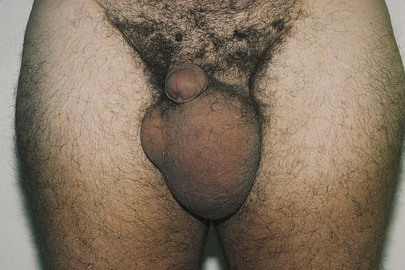

A common enlargement of the spermatic cord resulting from dilatation of the pampiniform plexus is a varicocele. These varicosities are usually on the left side, and the impression on palpation has been likened to feeling a bag of worms. Because the varicocele is gravity dependent, it is usually visible only while the patient is standing or straining. The patient is asked to turn his head and cough while the spermatic cords are held between the examiner’s fingers, as indicated previously. A sudden pulsation, especially on the left side, suggests the diagnosis of a varicocele. Although the diagnosis is usually made from palpation, large varicoceles may be discovered on mere inspection, as can be seen in the patient in Figure 15-27.

Figure 15–27 Varicocele.

Transilluminate Scrotal Masses

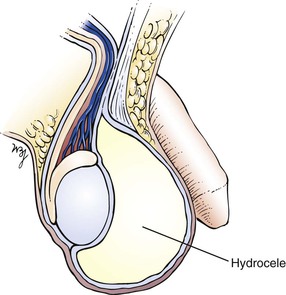

If a scrotal mass is detected, transillumination is necessary. In a darkened room, a light source is applied to the side of scrotal enlargement. Vascular structures, tumors, blood, hernias, and normal testicles appear opaque on transillumination. Transmission of the light as a red glow indicates a serous fluid–containing cavity, such as a hydrocele or a spermatocele. A hydrocele is an abnormal collection of clear fluid in the tunica vaginalis. The testicle is contained within this cystic mass, preventing actual palpation of the testis itself. By transillumination, it may be possible to view the orientation of the normal-sized testicle within the hydrocele. A spermatocele is a pea-sized, nontender mass that contains spermatozoa and is usually attached to the upper pole of the epididymis. A hydrocele, seen only as massive scrotal enlargement, is shown in Figure 15-28. Transillumination of a hydrocele in another patient is shown in Figure 15-29. A cross section of a hydrocele is illustrated in Figure 15-30.

Figure 15–28 Hydrocele.

Figure 15–29 Transilluminated hydrocele.

Hernia Examination

Inspect Inguinal and Femoral Areas

Although hernias may be defined as any protrusion of a viscus, or part of it, through a normal or abnormal opening, 90% of all hernias are located in the inguinal area. Commonly, a hernial impulse is better seen than felt.

Instruct the patient to turn his head to the side and to cough or strain. Inspect the inguinal and femoral areas for any sudden swelling during coughing, which may indicate a hernia. If a sudden bulge is seen, ask the patient to cough again, and compare the impulse with that of the other side. If the patient complains of pain while coughing, determine the location of the pain, and reevaluate the area.

Palpate for Inguinal Hernias

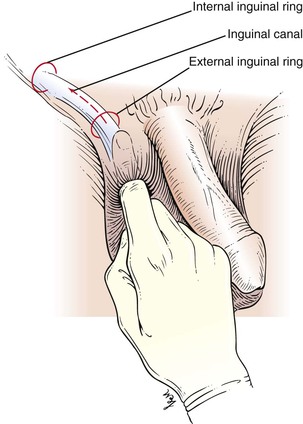

To palpate for inguinal hernias, the examiner places his or her right index finger in the patient’s scrotum above the left testis and invaginates the scrotal skin. There should be sufficient scrotal skin to reach the external inguinal ring. The finger should be placed with the nail facing outward and the pad of the finger inward. This is demonstrated in Figure 15-31. The examiner’s left hand may be placed on the patient’s right hip for better support.

Figure 15–31 Technique for examination for inguinal hernias.

The examiner’s right index finger should follow the spermatic cord laterally through the external inguinal ring, into the inguinal canal parallel to the inguinal ligament, and upward toward the internal inguinal ring, which is superior and lateral to the pubic tubercle. The external ring may be dilated and allow the finger to enter easily. The correct position of the right hand is shown in Figure 15-32 and is illustrated in Figure 15-33.

Figure 15–32 Technique for palpation of inguinal hernias.

With your index finger placed either against the external ring or in the inguinal canal, ask the patient to turn his head to the side and to cough or strain down. If a hernia is present, a sudden impulse against either the tip or the pad of the examining finger is felt. If a hernia is detected, have the patient lie down, and observe whether the hernia can be reduced by gentle, sustained pressure on the mass. If the hernia examination is performed with adequate scrotal skin and is done slowly, it is painless. The characteristics of hernias are discussed in the next section.

After the left side is evaluated, repeat the procedure by using your right index finger to examine the patient’s right side. Some examiners prefer to use the right index finger to examine the patient’s right side and the left index finger for the patient’s left side. Try both techniques to see which one is more comfortable for you.

If there is a large scrotal mass that appears opaque on transillumination, an indirect inguinal hernia may be present in the scrotum. Auscultation of the mass can be performed to determine whether bowel sounds are present in the scrotum, a useful sign in diagnosing an indirect inguinal hernia.

Examination of the prostate is discussed in Chapter 14, The Abdomen. If the rectal examination has not yet been performed, this is the appropriate time to examine the rectum and prostate.

Clinicopathologic Correlations

Gross hematuria that is usually painless is often the first indication of a urinary tract tumor, commonly located in the bladder. Table 15-1 lists the common causes of gross hematuria in different age groups and by sex.

Table 15–1

Causes of Hematuria by Age and Sex

| Age (Years) | Male | Female |

| Younger than 20 | Congenital urinary tract anomaly Acute glomerulonephritis Acute urinary tract infection |

— |

| 20–40 | Acute urinary tract infection Kidney stone Bladder tumor |

— |

| 40–60 | Bladder tumor Kidney stone Acute urinary tract infection |

Acute urinary tract infection Kidney stone Bladder tumor |

| Older than 60 | Prostatic disorder Bladder tumor Acute urinary tract infection |

Bladder tumor Acute urinary tract infection |

Scrotal disorders are relatively common. In a man with scrotal swelling, a careful history and a thorough physical examination often provide enough information for a correct diagnosis. Intrascrotal masses are common findings on physical examination. Although most masses are benign, testicular cancer is the leading solid malignancy in men younger than 35 years of age.

Some of the important considerations in the history include the patient’s age, time of onset of symptoms (if any), associated problems (e.g., fever, weight loss, dysuria), past medical history, and sexual history.

Intrascrotal masses can be categorized as acute or nonacute, intratesticular or extratesticular, and neoplastic or nonneoplastic.

Epididymitis is the most common cause of acute scrotal swelling. It accounts for more than 600,000 visits to physicians annually in the United States. It occurs in young, sexually active men and in older men with associated genitourinary problems. Patients usually complain of recent onset of testicular pain that is associated with fever, dysuria, and scrotal swelling. On examination, the epididymis is tender and indurated. The testis may also be enlarged and tender; this variant is called epididymo-orchitis.

Trauma is the third major cause of acute scrotal swelling. Trauma may produce a scrotal or testicular hematoma. An important fact to keep in mind is that 10% to 15% of patients with testicular tumors seek medical attention after trauma.

The most common types of intrascrotal pathologic conditions are the nonacute, nonneoplastic lesions. These include hydrocele, spermatocele, and varicocele. A hydrocele (see Fig. 15-28) is a collection of fluid within layers of the tunica vaginalis. It manifests as a painless swelling of the scrotum. A hydrocele may be congenital, acquired, or idiopathic. Acquired hydroceles may result from trauma, infection, renal transplantation, and neoplasm. Idiopathic hydroceles are the most common; patients may have no symptoms or may complain of a dull ache or scrotal heaviness. In general, hydroceles are anterior to the testis. They are smooth walled and can be transilluminated. Figure 15-29 depicts a transilluminated hydrocele.

Spermatoceles are cystic collections of fluid in the epididymis. They are frequently found on routine physical examination because they usually produce no symptoms. Because they are fluid filled, they can often be transilluminated.

A varicocele is a common intrascrotal mass resulting from abnormal dilatation of the veins of the pampiniform plexus. A man with a varicocele is usually asymptomatic but may have a history of infertility or a sensation of heaviness in the testicle or pain in the scrotum. Varicoceles are most frequently diagnosed when a patient is 15 to 30 years of age, and rarely develop after the age of 40. They occur in 15% to 20% of all males, and it is a common cause of male infertility. The varicocele can best be visualized by observing the patient in a standing position. A mass resembling a bag of worms may be seen and palpated superior to the testis. These varicosities typically enlarge during a Valsalva maneuver and are reduced when the patient lies down. Varicoceles are found predominantly on the left side. A right-sided varicocele suggests some obstruction of the inferior vena cava, whereas an acute left-sided varicocele may indicate a left-sided hypernephroma or other left renal tumor. Figure 15-27 shows a patient with a varicocele. Notice the markedly dilated veins in the scrotum.

Most testicular neoplasms are asymptomatic, but some patients may seek medical attention because of acute pain related to trauma, hemorrhage, hydrocele, and epididymitis. Other men may present with weight loss, fever, abdominal pain, lower extremity edema, or bone pain resulting from advanced metastatic disease. A history of cryptorchidism is important because of a high association between this condition and testicular malignancies. The most common finding on physical examination is a nodule or a painless swelling of one testicle. Approximately 1% to 3% of testicular neoplasms are bilateral. If found early, testicular carcinoma is almost always curable. Extratesticular tumors are uncommon and are usually benign. Pure seminomas constitute approximately 40% of all testicular cancer cases. Forty percent of testicular cancers have mixed histologic characteristics. As suggested by the American Cancer Society, all men between the ages of 15 and 35 should perform monthly a testicular self-examination.3 The patient is instructed to perform this test during or after a shower. This way, the scrotal skin is warm and relaxed. It is best to do the test while standing:

Any change in the shape of the testicle, the presence of a painless lump, or a swelling in the scrotum should be evaluated by a clinician.

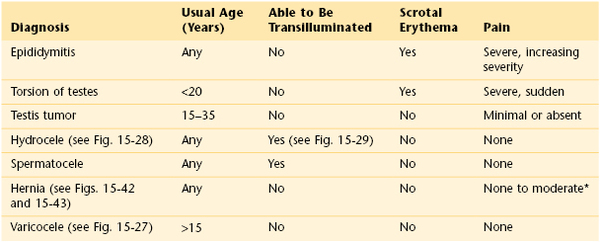

Table 15-2 provides a differential diagnosis of common scrotal swellings.

Table 15–2

Differential Diagnosis of Common Scrotal Swellings

* Unless the hernia is incarcerated, in which case pain may be severe.

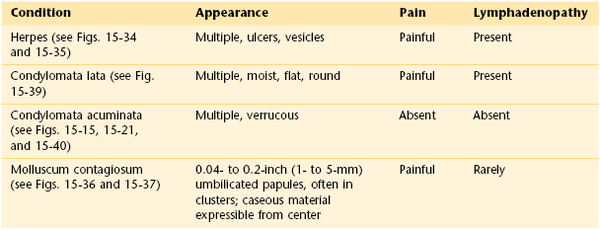

Sexually transmitted diseases are common. Of every 100 outpatient visits to a venereal disease clinic, 25% of men have gonorrhea, 25% have nongonococcal urethritis, 4% have venereal warts, 3.5% have herpes, 1.7% have syphilis, and 0.1% have chancroid. The incidence of both gonococcal and nongonococcal urethritis has increased dramatically since the early 1980s. On college campuses, 85% of urethritis is nongonococcal in origin.

Genital lesions of venereal diseases may be ulcerative or nonulcerative. The incidence of genital lesions has changed greatly since the 1950s. At one time, chancroid was common and herpes was rare; today, herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) infection is common, and chancroid is rare. Figure 15-34 shows the vesicular stage of a herpetic infection. Another example of HSV-2 infection is shown in Figure 15-35. Anal ulcerative lesions are becoming more common, particularly among gay men.

Figure 15–34 Herpes simplex virus type 2 infection.

Figure 15–35 Herpes simplex virus type 2 infection.

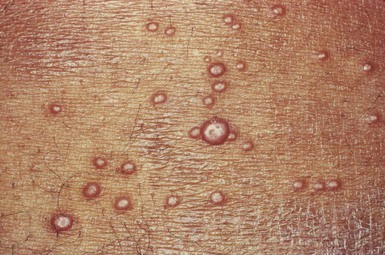

Molluscum contagiosum is a common, usually self-limited, cutaneous eruption affecting the skin and mucous membranes. It is often seen in the pediatric population and is caused by a large DNA poxvirus. Adults can acquire the infection through sexual contact with infected adults. The characteristic lesions are flesh-colored papules that range in size from pinpoint to 0.4 inch (1 cm) in diameter. The central depression is the most important diagnostic sign. The painful lesions may occur anywhere on the body: on the face and trunk in children and around the genitals of adults. Any adult with this disease must be screened for other sexually transmitted diseases. The lesions, as the name indicates, are highly contagious. As the lesions develop, there may be a surrounding patch of eczema. In patients with AIDS, the lesions become widespread, attaining sizes up to 0.8 inch (2 cm) in diameter. Figure 15-36 shows lesions of molluscum contagiosum of the penis. Figure 15-37 is a close-up photograph of the classic, umbilicated lesions of molluscum contagiosum. Table 15-3 lists a differential diagnosis of genital papular lesions.

Figure 15–36 Lesions of molluscum contagiosum of the penis.

The primary lesion of syphilis is the chancre (see Fig. 15-13), which occurs from 10 days to 3 weeks after infection at the site of the inoculation. The chancre is a painless ulcer with an indurated edge. It usually heals spontaneously within a month. If the patient is not treated for syphilis, the disease may evolve to the secondary stage. This occurs approximately 2 months after the appearance of the chancre. The patient may present with a widespread, nonpruritic, maculopapular rash over the genitalia, trunk, palms, and soles. There is a tendency for cropping of the lesions. The healed chancre may still be evident. There is also generalized lymphadenopathy. In the genital and perianal areas, the papules may coalesce and erode. These large, moist, painful papules, which look as if they were “pasted” on the skin, are called condylomata lata. They are covered with an exudate and are teeming with active spirochetes. If untreated, the patient may recover but may have a relapse of the eruption within 2 years. After this period, there is a long latent period during which the disease may progress to cardiovascular syphilis or neurosyphilis, a condition known as tertiary syphilis.

The skin lesions of syphilis are important to recognize. Figure 15-38 shows the typical skin lesions of secondary syphilis on the feet. Figure 15-39 shows condylomata lata in the perineum of the same patient. The healing chancre of primary syphilis is also seen on the penis of this patient.

Figure 15–38 Secondary syphilis lesions on the feet.

HPV infection of the genital tract is one of the most common sexually transmitted diseases among young adults and is the cause of venereal warts. In the United States, it is estimated that 20 million people have genital HPV infections at any one time, with 5.5 million acquiring it annually. Risk factors associated with HPV infection include younger age, belonging to an ethnic minority, alcohol consumption, and a high frequency of anal or vaginal sexual encounters. The annual cost burden in the United States of genital HPV infection is $6 billion, which makes it the second most costly sexually transmitted disease after human immunodeficiency virus infection. Condylomata acuminata are typically caused by HPV type 6 or HPV type 11, which are considered low-risk HPV types because these strains are rarely found in association with genital dysplasias or invasive cancer. Patients with immunodeficiencies are at higher risk for persistent HPV infection and progressive disease. Figure 15-40 shows the classic cauliflower lesions of condylomata acuminata on the penis of a renal transplant recipient (see also Figs. 15-15 and 15-21).

Figure 15–40 Condylomata acuminata of the penis.

Reiter’s syndrome is defined as the classic triad of nongonococcal urethritis, arthritis, and conjunctivitis. It most often affects men (20 : 1) during the third decade of life, and there is a high prevalence of human leukocyte antigen–B27. It is one of the most common causes of acute inflammatory arthritis in men. Approximately one third of patients with Reiter’s syndrome have a prodromal enteric or urethral inflammation. The most common enteric pathogens are Shigella, Salmonella, Yersinia, and Campylobacter; the most common urogenital pathogens are Chlamydia and Ureaplasma. Reiter’s syndrome is often associated with a psoriasis-like dermatitis on the palms and soles known as keratoderma blennorrhagicum. This painless, papulosquamous, “barnacle-like” eruption is pictured in Figure 15-41.

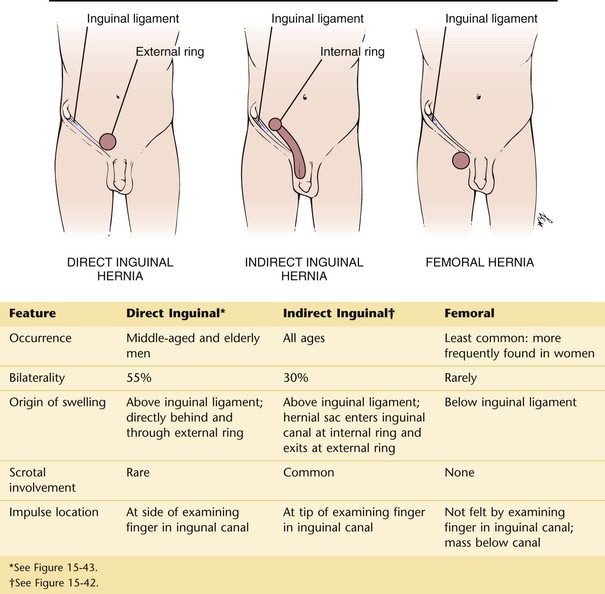

Hernias are common. The major types of external hernias are indirect and direct inguinal hernias and femoral hernias. Figure 15-42 shows a patient with a left indirect inguinal hernia. Figure 15-43 shows a patient with a small right direct inguinal hernia. Figure 15-44 illustrates and lists the major differences in the types of hernias.

Figure 15–42 Left indirect inguinal hernia.

Figure 15–43 Right direct inguinal hernia.

Figure 15–44 Differential diagnosis of hernias.

The bibliography for this chapter is available at studentconsult.com.

Bibliography

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2011. American Cancer Society: Atlanta; 2011.

American Cancer Society. Cancer facts and figures 2013. American Cancer Society: Atlanta; 2013.

American Cancer Society. Do I have testicular cancer? Testicular self-examination. [Available at] http://www.cancer.org/cancer/testicularcancer/moreinformation/doihavetesticularcancer/do-i-have-testicular-cancer-self-exam [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

American Cancer Society. Testicular cancer. [Updated May 14, 2012. Available at] http://www.cancer.org/acs/groups/cid/documents/webcontent/003142-pdf.pdf [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Baldwin K, Ginsberg P, Harkaway RC. Under-reporting of erectile dysfunction among men with unrelated urologic conditions. Int J Impot Res. 2003;15(2):87.

Bosl GJ, et al. Cancer of the testis. DeVita VT Jr, Hellman S, Rosenberg SA. Cancer: principles and practice of oncology. ed 7. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia; 2005.

Brown JS, et al. The sensitivity and specificity of a simple test to distinguish between urge and stress urinary incontinence. Ann Intern Med. 2006;144:715.

Brydøy M, et al. Paternity following treatment for testicular cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1580.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender health. [Updated December 19, 2012. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/lgbthealth/index.htm [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Male latex condoms and sexually transmitted diseases. Condoms and STDs: fact sheet for public health personnel. [Updated December 4, 2012. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/condomeffectiveness/latex.htm [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually transmitted diseases surveillance 2011. [Updated January 23, 2013. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats11/default.htm [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Trends in sexuality transmitted diseases in the United States: 2009 national data for gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis. [Updated November 22, 2010. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats09/trends.htm [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vaccine information statement (interim) human papillomavirus (HPV) Gardasil. [February 22, 2012. Updated May 17, 2013. Available at] http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/hcp/vis/vis-statements/hpv-gardasil.html [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Conron KJ, Mimiaga MJ, Landers SJ. A population-based study of sexual orientation identity and gender differences in adult health. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:1953.

Del Mistro A, Chieco Bianchi L. HPV-related neoplasias in HIV-infected individuals. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:1227.

Espey DK, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1975–2004, featuring cancer in American Indians and Alaska Natives. Cancer. 2007;110:2119.

Feldman HA, et al. Impotence and its medical and psychological correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 1994;151:54.

Fosså SD, et al. Risk of contralateral testicular cancer: a population-based study of 29,515 U.S. men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2005;97:1056.

Garland SM, et al. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent ano-genital diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1928.

Hebernick D, et al. Sexual activity in the United States: results from a national probability sample of men and women ages 14-94. J Sex Medicine. 2010;7(Suppl 5):255.

Hodges FM. The ideal prepuce in ancient Greece and Rome: male genital aesthetics and their relation to lipodermos, circumcision, foreskin restoration, and the kynodesme. Bull Hist Med. 2001;75:375.

Johannes CB, et al. Incidence of erectile dysfunction in men 40 to 69 years old: longitudinal results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 2000;163:460.

Kuthe A. Phosphodiesterase 5 inhibitors in male sexual dysfunction. Curr Opin Urol. 2003;13:405.

Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281:537.

Leitzmann MF, et al. Ejaculation frequency and subsequent risk of prostate cancer. JAMA. 2004;291:1578.

Lin K, Sharangpani R. Screening for testicular cancer: an evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:396.

Markland AD, et al. Incontinence. Med Clin North Am. 2011;95:539.

McVary KT. Clinical practice: erectile dysfunction. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:2472.

Medline Plus. Testicular self examination. [Available at] http://www.nlm.nih.gov/medlineplus/ency/article/003909.htm [Updated January 24, 2013. Accessed February 18, 2013] .

Montgomery JS, Bloom DA. The diagnosis and management of scrotal masses. Med Clin North Am. 2011;95:235.

Montorsi F, et al. Pharmacological management of erectile dysfunction. BJU Int. 2003;91:446.

National Cancer Institute. Testicular cancer screening. Health professional version. [Updated January 26, 2012. Available at] http://www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/screening/testicular/healthprofessional/allpages [Accessed January 31, 2013] .

Qaseem A, et al. Clinical guidelines: hormonal testing and pharmacologic treatment for erectile dysfunction: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:639.

Rosen RC, et al. The International Index of Erectile Function (IIEF): a multidimensional scale for assessment of erectile dysfunction. Urology. 1997;49:822.

Schouten VW, et al. Erectile dysfunction prospectively associated with cardiovascular disease in the Dutch general population: results from the Krimpen Study. Int J Impot Res. 2008;20:92.

U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for testicular cancer. U.S. Preventive Services Task Force reaffirmation recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154:483.

Van den Belt-Dusebout AW, Nuver J, de Wit R, et al. Long-term risk of cardiovascular disease in 5-year survivors of testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:467.

Wampler SM, Llanes M. Common scrotal and testicular problems. Prim Care. 2010;37:613.

Wein AJ, et al. Campbell-Walsh urology. Elsevier Saunders: Philadelphia; 2012.