Malaria

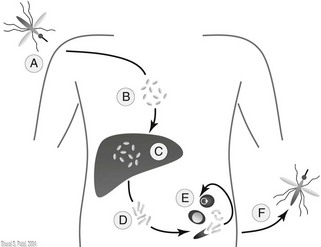

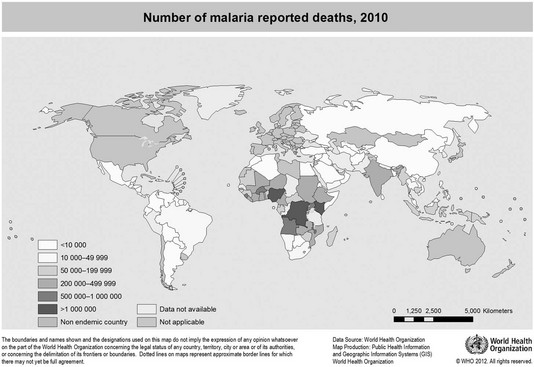

Malaria is a mosquito-transmitted, blood-borne, parasitic infection present throughout tropical and developing areas of the world. Parasites are transmitted by 30 to 40 (out of 430) species of the female Anopheles mosquito, which tends to bite between dusk and dawn. Estimated worldwide incidence is 500 to 800 million cases per year. Malaria infection causes a severe febrile illness that is potentially fatal, with most deaths occurring from Plasmodium falciparum infection in children in sub-Saharan Africa. Plasmodium sporozoites enter the bloodstream following inoculation from the mosquito and pass to the liver, where they develop into schizonts. Hepatic cells containing schizonts then rupture, releasing merozoites that then invade erythrocytes. These further develop into trophozoites or gametocytes within the erythrocyte. Free gametocytes invade the intestinal wall of feeding mosquitoes and develop into sporozoites, thus perpetuating the cycle of inoculation (Fig. 47-1). Pathologic presentations of malaria, such as fever and anemia, occur during the asexual phase of the parasitic infection, in which the malaria parasite invades the healthy erythrocytes (erythrocytic phase). Parasitic replication over the subsequent 2 to 3 days following initial infection of healthy erythrocytes is followed by cell rupture and subsequent exponential parasite reproduction.

Five species of malaria typically cause disease in humans:

1. Plasmodium vivax (worldwide distribution, but uncommon in sub-Saharan Africa)

2. P. falciparum (worldwide distribution, predominant in sub-Saharan Africa, Amazon basin, Haiti, limited in Asia and Oceania)

3. Plasmodium ovale (West Africa, Amazon basin)

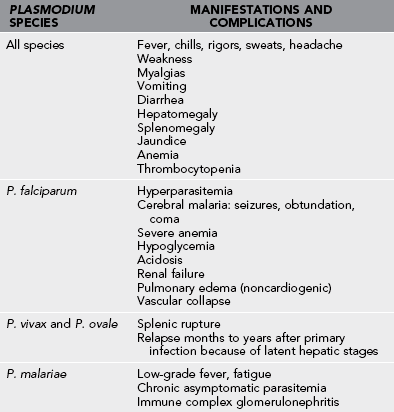

Clinical Manifestations and Complications (Table 47-1)

1. Clinical manifestations first evident 1 to 2 weeks after entry into endemic area (sooner if infected blood obtained through transfusion or shared needles)

2. No pathognomonic signs, but common symptoms (Table 47-2)

Table 47-2

Common Symptoms and Their Incidence in Malaria

| SYMPTOM | INCIDENCE (%) |

| Fever | 97 |

| Chills | 97 |

| Headaches | 94 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 62 |

| Abdominal pain | 56 |

| Myalgia | 50 |

| Backache | 9 |

| Dark urine | 3 |

3. Paroxysms of chills followed by high fever and sweating

a. May last several hours and occur every 2 to 3 days

b. Classic periodic attacks often not observed in severe P. falciparum malaria; fever possibly constant

5. Cerebral malaria (associated with high levels of P. falciparum parasitemia), characterized by high fevers, confusion, seizures, and eventually coma and death

6. Acute renal failure, pulmonary edema

7. Definitive diagnosis only by the presence of parasite-containing red blood cells (detected on thick and thin blood smears [see Plate 33])

8. Clinical attacks during the first 4 to 8 weeks after return from the area of exposure

9. Prolonged latent incubation times (up to 3 years) reported

10. Complications are more common with P. falciparum infection than with other species of malaria.

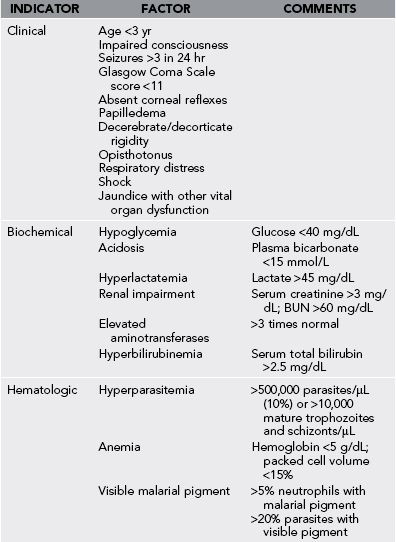

11. Factors indicating a poor prognosis for persons with severe malaria include clinical, biochemical, and hematologic features (Table 47-3).

Prevention

Chemoprophylaxis: General Principles

1. Determine the risk for malaria infection for a geographic location (Fig. 47-2).

a. Use the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Internet site (http://www.cdc.gov/travel/) for up-to-date changes in malaria risk worldwide.

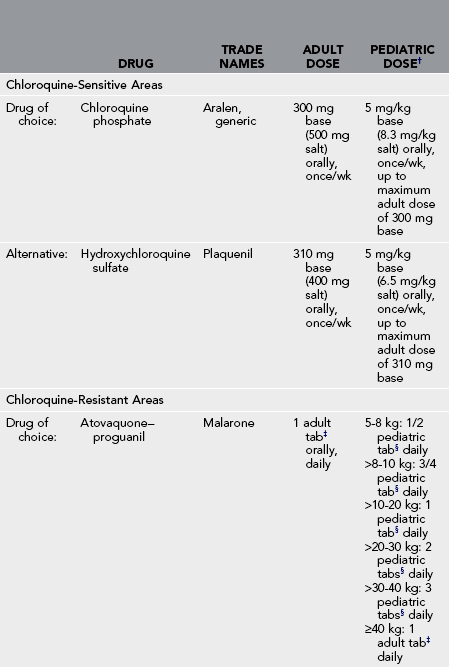

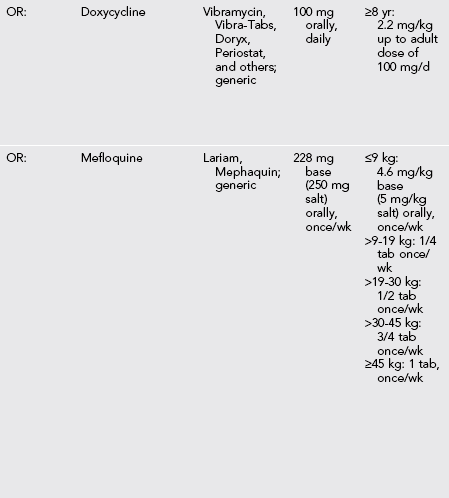

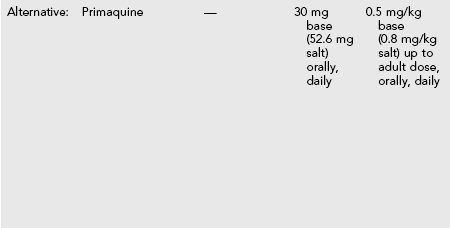

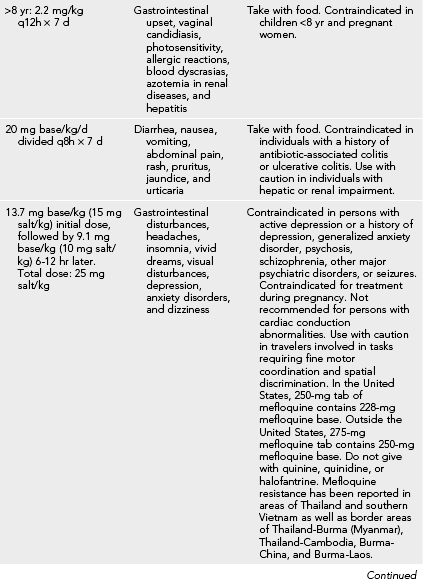

2. Chemoprophylaxis (Table 47-4) should be prescribed for nonimmune individuals, including children traveling to malaria-endemic areas. The health care provider must consider several factors when choosing an appropriate chemoprophylactic regimen for the traveler. These include destination-specific malaria risk and resistance patterns, age, underlying medical conditions, allergies, tolerability, and length of stay. Pediatric dosages are based on weight and should never exceed adult dosages.

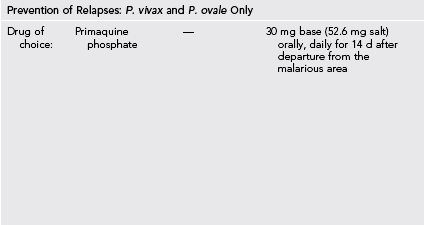

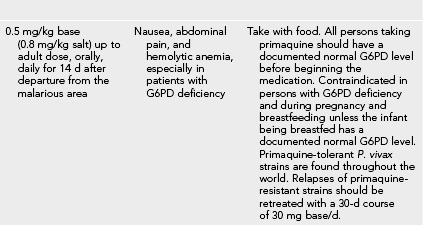

Table 47-4

Medications Used for Prevention of Malaria*

G6PD, Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase.

*Caused by Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium ovale, Plasmodium vivax, and Plasmodium malariae.

†Should never exceed adult dose.

‡Adult tabs contain 250 mg atovaquone and 100 mg proguanil hydrochloride.

§Pediatric tabs contain 62.5 mg atovaquone and 25 mg proguanil hydrochloride.

a. Be aware that resistance to multiple antimalarial drugs has made prevention and treatment of P. falciparum malaria a major problem in some endemic areas (Fig. 47-3).

FIGURE 47-3 Geographic distribution of mefloquine-resistant malaria. (From Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: CDC health information for international travel 2012: The yellow book, New York, 2012, Oxford University Press. From Map 3-11, http://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/pdf/yellowbook-2012-map3-11-distribution-mefloquine-resistant-malaria.pdf. Courtesy Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.)

3. Start administration of the antimalarial drug 1 to 2 weeks (chloroquine or mefloquine) or 1 to 2 days (doxycycline or atovaquone–proguanil) before departure to allow time to accomplish the following:

a. Become familiar with any drug side effects.

b. Switch to an alternative drug if necessary.

4. Maintain the antimalarial drug-dosing schedule during exposure.

5. Continue the antimalarial drug regimen for 4 weeks (chloroquine, mefloquine, and doxycycline) or 7 days (atovaquone–proguanil) after leaving the area of malaria infection.

Other Malaria Prevention Strategies

1. Apply behavioral modification strategies.

a. Limit exposure to mosquitoes (e.g., time spent outdoors, particularly at dusk and during nighttime).

b. Use physical barriers such as screens, doors, nets, and curtains.

c. Wear protective clothing (long sleeves and long pants when possible, sprayed or impregnated with insecticide).

d. Use mosquito bed nets (sprayed or impregnated with insecticide).

2. Insect repellents and insecticides are highly recommended as adjuncts to malaria chemoprophylaxis. They provide additional protection from insect-transmitted infections that have no vaccines or chemoprophylaxis. The most effective insect repellent for skin application contains N,N-diethyl-3-methylbenzamide (DEET). Examples include the following:

a. Ultrathon Insect Repellent: 35% DEET in polymer formulation; provides up to 12-hour protection against mosquitoes; also effective against ticks, biting flies, chiggers, fleas, and gnats

b. DEET Plus Insect Repellent: 17.5% DEET with 2.5% R 326; apply q4h for mosquitoes, q8h for biting flies

c. Skedaddle Insect Protection for Children: 10% DEET using molecular entrapment technology

3. Permethrin-containing spray insecticide is effective for external clothing and mosquito nets. Examples include the following:

b. Duranon Tick Repellent: permethrin in a formula lasting up to 2 weeks; repels ticks, chiggers, and mosquitoes

4. Partial immunity can be stimulated by repeated infections in residents of malaria-endemic areas; however, this immunity is gained at the expense of chronic anemia and is lost when residents go abroad for work or study.

5. Malaria vaccines are being investigated and may become available in the future.

Treatment of Uncomplicated Malaria

Presumptive Self-Treatment

1. If treatment is required, it implies failure of malaria chemoprophylaxis. Taking prophylactic medications does not exclude the possibility of becoming infected because no current drug or drug regimen provides 100% protection against malaria.

2. Presumptive self-treatment should be used only as an interim measure, and travelers should be advised to seek medical evaluation as soon as possible so that thick and thin blood smears can be obtained for precise diagnosis.

3. Presumptive self-treatment should be taken immediately if the traveler develops an influenza-like illness with fevers and chills and professional medical care is not available within 24 hours.

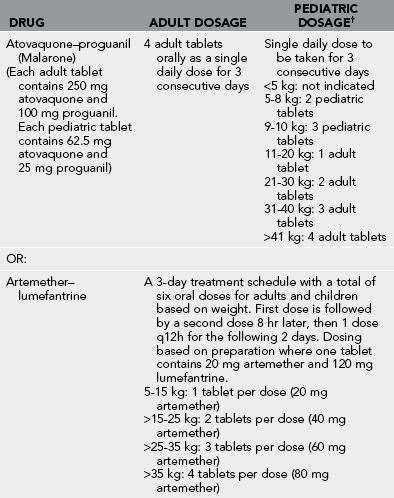

Note the drugs used for the treatment of presumed malaria infection (Table 47-5). Have the patient take a treatment dose of one of the antimalarial agents when signs and symptoms suggest an acute attack and prompt medical attention is not available.

General Approach

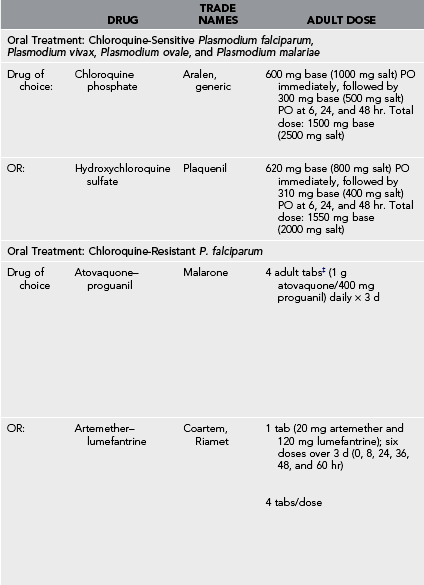

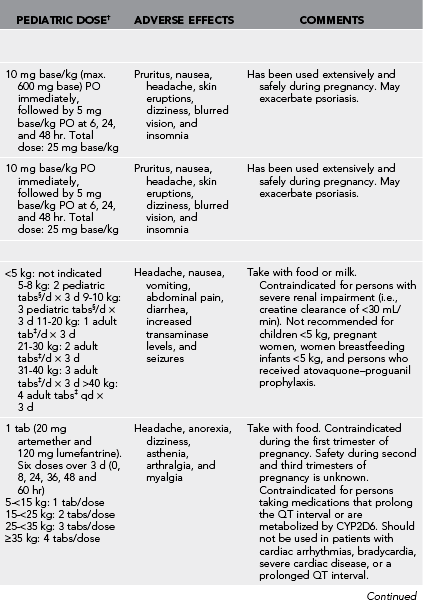

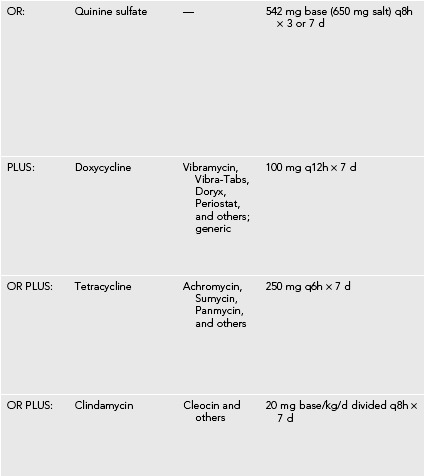

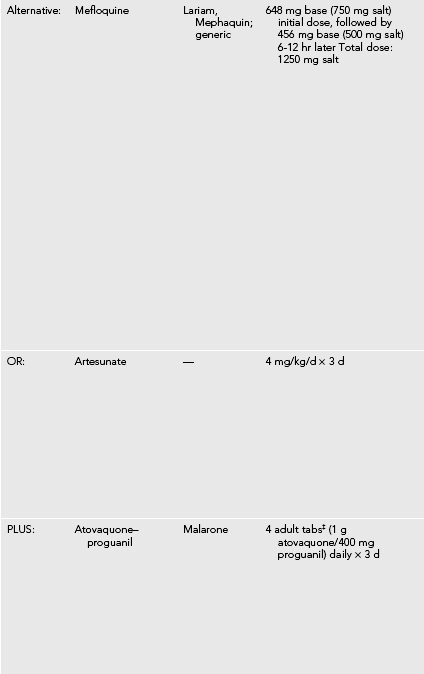

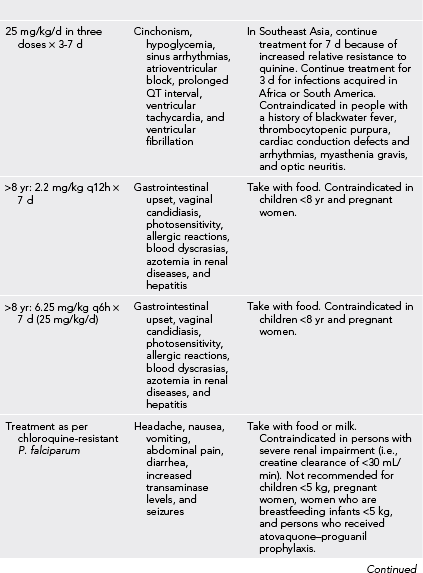

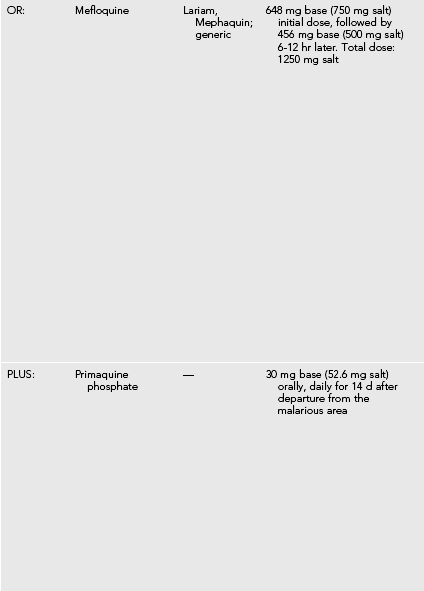

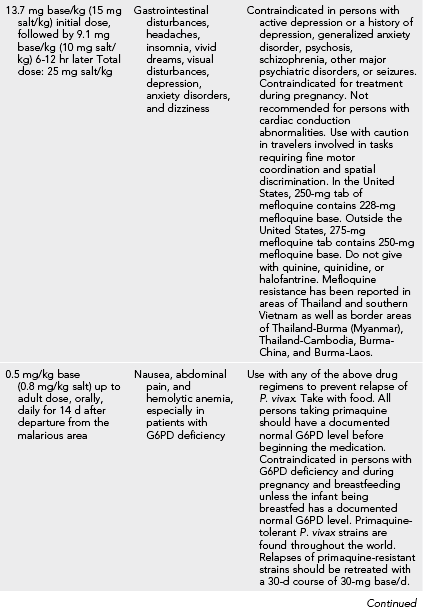

1. Malaria treatment consists of rapid and appropriate antimalarial therapy (Table 47-6), as well as supportive care.

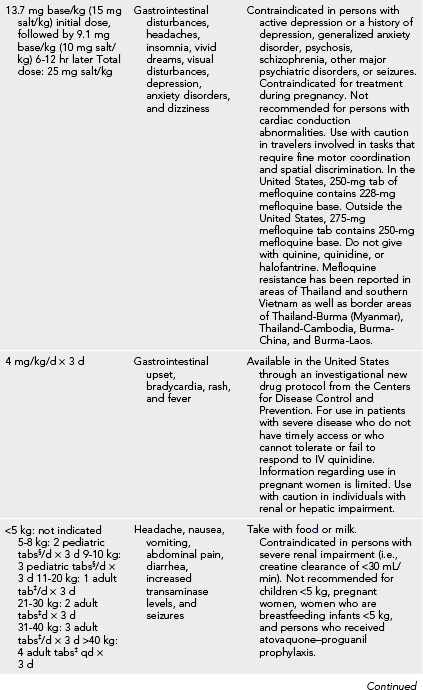

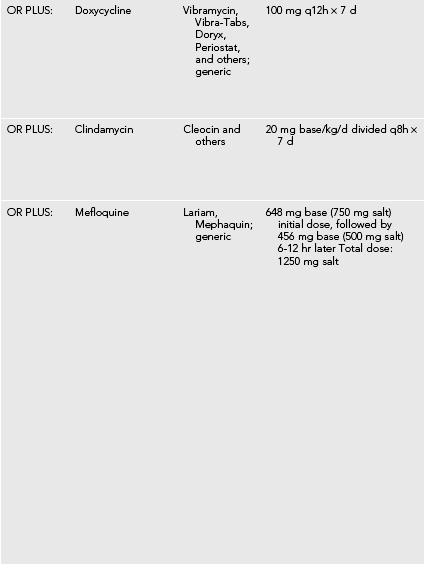

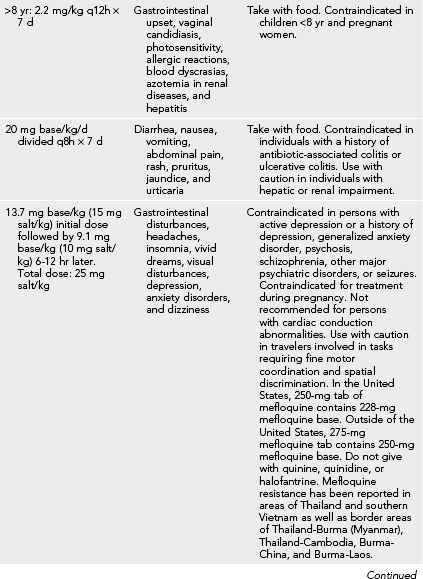

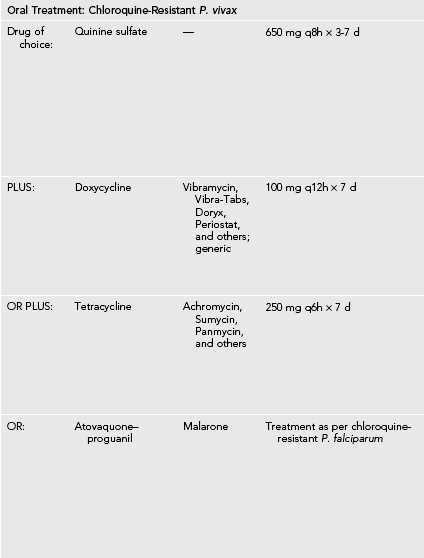

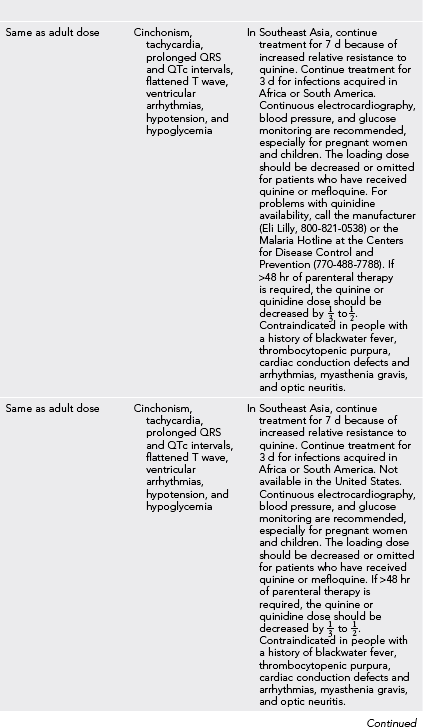

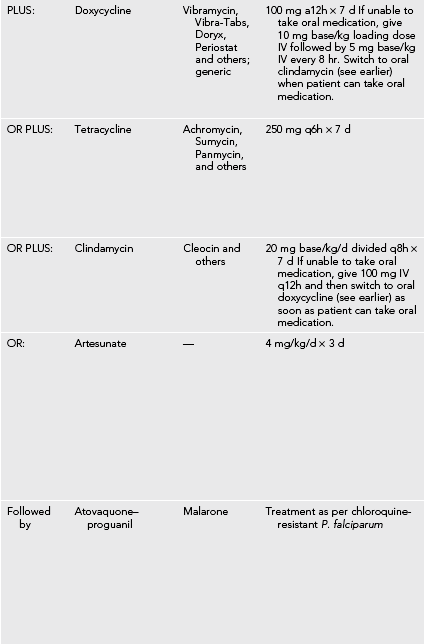

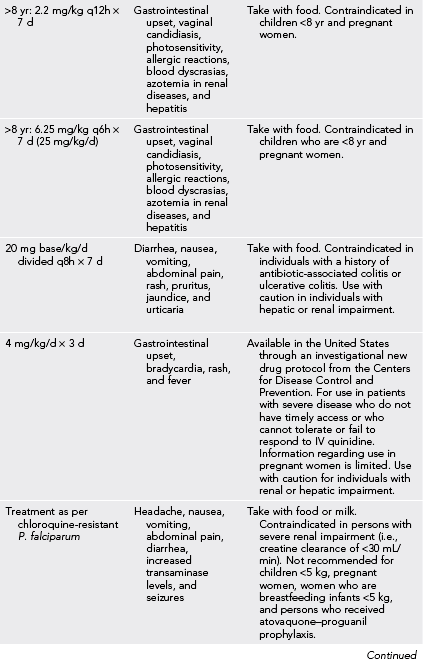

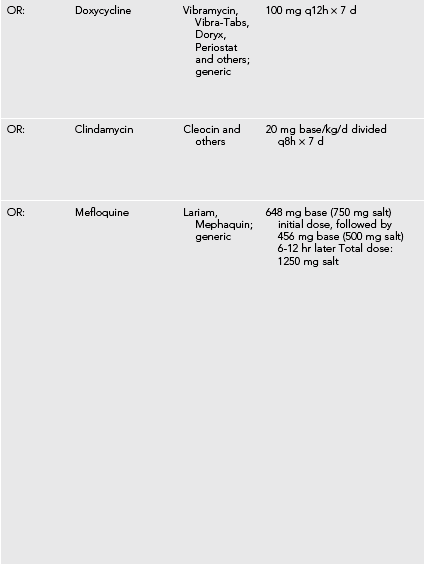

Table 47-6

Medications for the Treatment of Malaria*

G6PD, Glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; IV, intravenously.

*Caused by Plasmodium falciparum, Plasmodium ovale, Plasmodium vivax, and Plasmodium malariae in the United States.

†Should never exceed the adult dose.

‡Adult tabs contain 250 mg atovaquone and 100 mg proguanil hydrochloride.

§Pediatric tabs contain 62.5 mg atovaquone and 25 mg proguanil hydrochloride.

2. Therapeutic agents should be chosen based on prophylaxis used (if any), age of the patient, pregnancy and lactation status, species of malaria and their reported resistance patterns endemic to the region of likely inoculation, drug availability, cost, and side effects.

3. Care should be taken to assess for signs or symptoms of severe malaria (see Table 47-3).

4. Patient can be given acetaminophen (paracetamol) 1 g PO q6h to q8h or 15 mg/kg/dose q6h to q8h in children.

5. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs should be avoided because of the possible renal complications of malaria.

6. Oral hydration should be continued because patients often have insensible losses through fever, nausea, and vomiting.

Treatment of Chloroquine-Sensitive P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, and P. malariae

1. Chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine are the drugs of choice for infections with chloroquine-susceptible malarial parasites (see Table 47-6). These drugs have excellent oral absorption and can be administered via nasogastric tube in patients with impaired consciousness.

2. Parenteral quinidine or quinine is recommended for patients unable to take oral chloroquine.

3. Drug administration, blood pressure, cardiac rhythms, and blood glucose levels should be monitored closely during intravenous administration of quinidine or quinine.

4. It is reasonable in nondiabetic patients to give empiric dextrose IV before quinidine or quinine administration, because patients may be hypoglycemic as a result of the parasitic infection itself.

5. For patients with P. vivax or P. ovale infections, treatment should be followed by a course of primaquine.

Treatment of Chloroquine-Resistant P. falciparum

1. In the United States, quinidine is preferred over quinine because it is faster acting, blood levels can be followed, and it is more available.

2. Patients not improving initially with parenteral quinidine or quinine should have doxycycline, tetracycline, or clindamycin added to their regimen.

3. If tolerating oral medications (or via nasogastric tube), atovaquone–proguanil, artemether–lumefantrine, or mefloquine can also be used (see Table 47-6).

4. Outside of the United States, severe malaria should be treated with intravenous artesunate, or alternatively intramuscular artemether or oral artemisinin combination therapies (ACTs) because they clear parasitemia and coma more rapidly than do quinidine and quinine. Uncomplicated cases can be treated with a full course of oral ACTs alone. Parenteral quinidine and quinine, however, can also be used (see Table 47-6).

5. Duration of quinidine or quinine therapy should be at least 3 days in Africa or South America, and 7 days in Southeast Asia because of increased relative resistance.

6. Because of drug resistance, mefloquine should not be used to treat malaria infections acquired in Southeast Asia.

Treatment of Severe Malaria

1. Outside of the United States, artesunate IV or IM is the preferred therapy for severe P. falciparum malaria (see Table 47-6).

2. Alternatively, artemether 3.2 mg/kg IM first dose then 1.6 mg/kg IM q24h (adults and children) or quinine/quinidine IV or IM are acceptable if artesunate is not available (see Table 47-6).

Supportive Care for Severe Malaria

1. Patients should be assessed for severe anemia, dehydration, hypoglycemia, acidosis, anemia, hypoxemia, and pulmonary edema.

2. Patients receiving IV quinine derivatives should be placed on a cardiac monitor, if available, and have frequent blood pressure measurements.

3. Quinine or quinidine derivatives should be given with a continuous infusion of 5% to 10% dextrose, with blood glucose measurements every 4 to 6 hours.

4. Patients exhibiting renal failure treated with quinine derivatives should have their maintenance doses decreased by 30% to 50%.

5. Benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam, lorazepam) should be used for treatment of seizures. Phenobarbital should be avoided because it may worsen clinical outcomes and mortality. Antibiotics that treat bacterial meningitis should be initiated until a lumbar puncture can be performed to exclude the diagnosis of meningitis.

6. Broad-spectrum antibiotics should be started in conjunction with parenteral antimalarial therapy because patients with severe malaria may have concurrent bacterial infections and sepsis (see Appendix H).

7. Blood transfusion should be delayed until absolutely necessary (e.g., hemoglobin <5 g/dL with hemodynamic instability) because blood supplies in developing countries may be poorly monitored for quality and infection.

8. If blood products are to be given, consider exchange transfusion or interval loop diuretics to prevent fluid overload and pulmonary edema in the setting of acquired kidney injury.

9. Therapeutic efficacy can be monitored by checking sequential blood smears.