Chapter 11 MALABSORPTIVE DISORDERS AND COELIAC DISEASE

INTRODUCTION

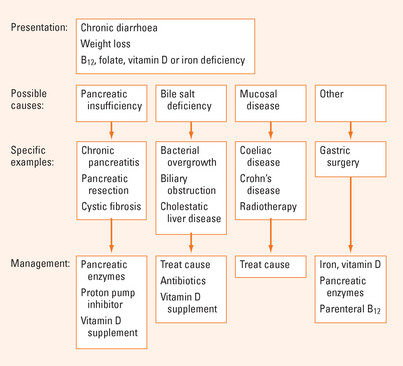

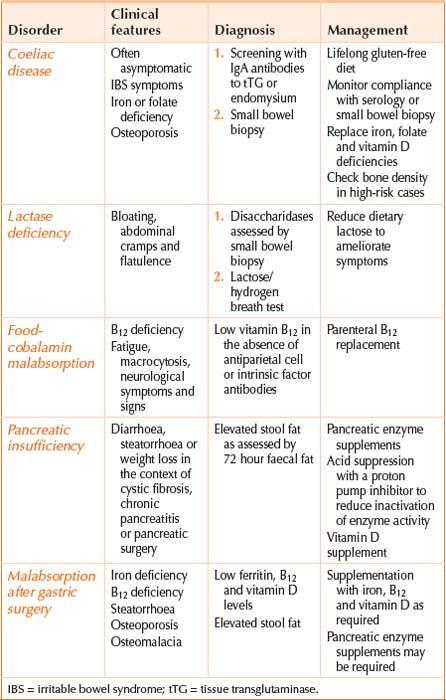

The body obtains nutrients from food by the absorption of food components that have been broken down by digestion. Malabsorption is the failure of the processes of digestion and absorption, and may present with weight loss, bloating, diarrhoea and a myriad of specific vitamin and nutrient deficiencies. Identification of the underlying cause and replacement of vitamin and nutrient deficiencies are the cornerstones of management (see Figure 11.1). An aetiologic classification of malabsorption is listed in Table 11.1 with the types commonly seen in clinical practice summarised in Table 11.2.

| Pancreatic insufficiency |

BILE SALT DEFICIENCY

Bacterial overgrowth

In health, the bacteria that are cultured from the small intestinal lumen are transiently present in counts of less than 104 per mL of jejunal content. Stasis of luminal contents due to impaired motility or structural abnormalities can result in bacterial overgrowth. Excess bacteria can produce malabsorption by deconjugating bile salts, rendering them inadequate for micelle formation and fat digestion. Bacterial-induced B12 deficiency may also occur.

MUCOSAL DISEASE

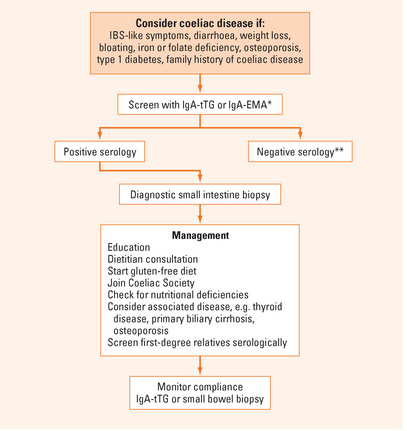

Coeliac disease

In patients with coeliac disease, wheat proteins known as gluten and their equivalents in rye and barley trigger an immune response in the mucosa of the small intestine. These proline-rich proteins resist digestion and are deamidated by an enzyme known as tissue transglutaminase in the intestinal mucosa. Antigen presenting cells with specific HLA heterodimers on their surface (HLA-DQ2 in 95% and HLA-DQ8 in 5% of cases) present the antigen to CD4+ T cells resulting in an immune response that leads to mucosal damage characterised by intraepithelial lymphocytosis, villous atrophy and crypt hyperplasia. This mucosal damage or enteropathy is most marked in the proximal small intestine and impairs absorption.

Diagnosis

A flow diagram summarising the diagnosis and management of coeliac disease is shown in Figure 11.1.

Testing for coeliac disease is only reliable in individuals consuming a gluten-containing diet.

In studies comparing controls with coeliac cases known to have villous atrophy on small intestine biopsy, antibodies to endomysium (IgA-EMA) and tissue transglutaminase (IgA-tTG) have been shown to have a 90%–100% sensitivity and specificity and are the recommended tests for serological screening. The IgA antigliadin antibody has approximately an 80%–90% sensitivity and specificity. The sensitivity of all of these assays is lower in cases with lesser degrees of histologic abnormality (e.g. intraepithelial lymphocytosis or crypt hyperplasia only). In IgA-deficient individuals serologic testing with IgG antibodies to the same antigens is known to have a much lower sensitivity for coeliac disease (around 30%).

A small intestine biopsy on a gluten-containing diet is essential to confirm a diagnosis of coeliac disease. An increased number of lymphocytes in the small intestine epithelium (intraepithelial lymphocytosis) is the earliest abnormality on routine histology, but only a minority of patients (10%) with this finding will have coeliac disease, as assessed by positive serology. Crypt hyperplasia and partial or complete villous atrophy are typical findings that are diagnostic in the presence of positive serology.

MALABSORPTION AFTER GASTRIC SURGERY

Partial or total gastrectomy is commonly associated with malabsorption of fat, iron, vitamin B12 and vitamin D. Gastric atrophy with loss of acidity, rapid transit, impaired pancreatic stimulation and asynchronous pancreatic and biliary secretions contribute. Monitoring after surgery facilitates early replacement of any deficiencies.

FOOD-COBALAMIN MALABSORPTION

The most common cause of B12 deficiency is food-cobalamin malabsorption, where vitamin B12 (also known as cobalamin) cannot be liberated from food or intestinal transport proteins (70% of cases). Age-related gastric atrophy, metformin use, acid suppression with proton pump inhibitors, gastrectomy and alcohol abuse can contribute to food-cobalamin malabsorption. Less common causes of B12 deficiency include a dietary deficiency of B12 in strict vegetarians (5% of cases) and pernicious anaemia (20% of cases). Testing for antibodies to intrinsic factor and parietal cells will identify pernicious anaemia, which causes an autoimmune gastritis of the gastric body and fundus with impaired acid and intrinsic factor secretion. Antibodies to intrinsic factor have 50% sensitivity and 90% specificity for the diagnosis of pernicious anaemia, respectively, while antiparietal cell antibodies have a 90% sensitivity and 50% specificity. Currently B12 deficiency is treated by parenteral vitamin B12 replacement but there is increasing evidence that oral replacement may be satisfactory in many cases provided large doses of 0.5–1 mg are taken daily.

Andres E, Loukili NH, Noel E, et al. Vitamin B12 (cobalamin) deficiency in elderly patients. CMAJ. 2004;171(3):251-259.

Dewar DH, Ciclitira PJ. Clinical features and diagnosis of celiac disease. Gastroenterology. 2005;128(4 Supplement 1):S19-S24.

DiMagno EP. Gastric acid suppression and treatment of severe exocrine pancreatic insufficiency. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;15(3):477-486.

Riley SA, Marsh MN. Maldigestion and malabsorption. In Feldman M, Freidman LS, Brandt LJ, editors: Sleisenger and Fordtran’s gastrointestinal and liver disease: pathophysiology, diagnosis, management, 8th edn., Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2006.