16 Making the apprenticeship model and work-based learning more effective

The apprenticeship

In the nineteenth century and earlier, doctors were trained as apprentices to practising doctors. The master accepted the pupil, who paid for the privilege and was taught and instructed in the methods and secrets (Calman 2006). In the late nineteenth and early part of the twentieth century the lack of attention to the scientific basis of medicine in undergraduate education and the varying quality of the apprenticeship experience offered led to a significant shift towards a university-based education. The emphasis was placed on more formal and theoretical education in the classroom and on the didactic lecture.

Principles

• taking responsibility for seeking out and engaging in learning experiences

• being actively involved in the context of the task being undertaken in the work situation

• reflecting on their learning experiences with mentors, supervisors, teachers and peers

• interacting with colleagues and other members of the healthcare team

• receiving on-going feedback from mentors, supervisors, teachers and peers.

Advantages

Learning on the job in the clinical environment offers a number of advantages:

• WBL focuses on real problems in the context of professional practice. Relevance, a key principle for effective learning as described in the FAIR model in Chapter 2, is a feature. It provides students/trainees with the satisfaction of doing a ‘real job’ in an authentic work setting rather than engaging in an academic exercise.

• WBL requires active participation and feedback – two other elements in the FAIR model. In WBL students learn more effectively through doing and through opportunities to practise, particularly when feedback is provided.

• WBL by its very nature can be designed to meet the needs of the learner – individualisation is the fourth component of the FAIR model.

• WBL offers a multi-professional experience that can help students and trainees to work as a member of a team and develop their professional identity.

• Experience on the job can help students and trainees to make a career choice.

• Students’ on-the-job experience, such as shadowing house officers in their final year as medical students, may prepare them for their subsequent posting after qualification. It helps them to become familiar with the work environment in the context of healthcare delivery. It may also help to enhance employment prospects for a particular post.

Implementation

• Plan the experience carefully, matching the learning experiences to the expected learning outcomes. What conditions are the student or trainee expected to see and what procedures are they expected to carry out? Unless planned carefully the school of experience is no school at all.

• Make the expectations explicit and draw up and agree a learning plan with the students/trainees.

• Monitor the learners’ progress and provide constructive and timely feedback.

• Recognise the potential contributions of other members of the healthcare team to the students’ and trainees’ on-the-job experiences. The development of satisfactory relationships is an essential part of the exercise.

• Recognise the importance of the education environment. Students or trainees who are made to feel welcome are more likely to engage actively in the full range of learning opportunities provided and are more likely to play an active role within the team (Fig. 16.1). The concept of the education environment is explored in Chapter 18.

• Make medical students an integral part of the patient’s care. This may involve the student participating in ward rounds and in some aspects of the patient’s management. A student’s notes for example may become part of a patient’s records, although this and other students’ participation can present a legal challenge.

• The learner may benefit from a job aid that provides step-by-step guidelines on the task expected of them. This is particularly important when the task is lengthy or complex, and when the consequence of error is high. The job aid may be presented in print format or electronically through a mobile device.

• A study guide can help the student or trainee to understand what is expected of them in the work place and how they can obtain the maximum educational benefit from their experiences. The guide will help to relate these experiences to the other elements of the training programme and to relate theory to practice. Additional learning experiences such as the use of simulators that may enrich their experiences in the clinical setting are identified. The use of study guides is described in Chapter 13.

Problems and pitfalls

Problems and difficulties may be encountered when WBL is implemented:

• The learning may be opportunistic and based solely on the patients seen by the student or trainee. Some repetition of experiences is useful but unnecessary repetition should be avoided. Otherwise the learner is in danger of becoming like the golfer who continues to practise his or her mistakes but does not improve their game.

• The level of responsibility allocated to students or trainees in the delivery of the health care to the patients may present a problem. It is important that learners are not given tasks beyond their capabilities or authority.

• A conflict is sometimes perceived between the educational needs of the doctor in training and the service delivery demands. In WBL the relationship between the education and service components should be made explicit and the education integrated with the service delivery.

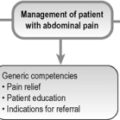

• The learners’ progress needs to be carefully monitored and appropriate feedback provided. Inappropriate or lack of feedback is a common criticism in WBL (Fig. 16.2). The assessment of the students’ progress and their achievement of the learning outcomes can be challenging. Non-traditional methods of assessment may be required and these are discussed in Chapter 31.

• There may be funding implications for the medical school in undergraduate education where money follows the student and in postgraduate training for the hospital where the employment of junior staff may attract high insurance premiums.

Reflect and react

1. The work environment has powerful learning potential and can meet the criteria for effective and efficient learning. Is this potential fully achieved with your trainees?

2. As a teacher or trainer think about how you can facilitate and guide learning on the job and provide feedback to the trainee or student.

3. Is there a study guide available to support the student’s or trainee’s learning? If not, consider preparing one. Extracts from a study guide prepared to support junior doctors during their paediatric training are given in Appendix 4.

Laidlaw J.M., Harden R.M., Robertson L.J., et al. The design of distance-learning programmes and the role of content experts in their production. Med. Teach.. 2003;25:182-187.

The preparation of a study guide for trainee surgeons is described.

Mitchell H.E., Harden R.M., Laidlaw J.M. Towards effective on-the-job learning: the development of a paediatric training guide. Med. Teach.. 1998;20:91-98.

Swanwick T. Informal learning in postgraduate medical education: from cognitivism to ‘culturism’. Med. Educ.. 2005;39:859-865.

Calman K. Medical Education: Past, Present and Future. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2006.

An interesting account of the history of medical education.

Hargreaves D.H., Bowditch M.G., Griffin D.R. On-The-Job Training for Surgeons. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press; 1997.

Hargreaves D.H., Southworth G.W., Stanley P., Ward S.J. On-The-Job Training for Physicians. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press; 1997.