Major Complications Associated With Laparoscopic Surgery

A number of complications may be associated with laparoscopic surgery. Several of these iatrogenic injuries are unique and peculiar to the laparoscopic procedure itself (i.e., separate from the major surgical objective). For example, total abdominal hysterectomy is associated with the risk of a number of complications inherent to the surgical procedure, whereas laparoscopic hysterectomy has risks associated with the laparoscopic approach plus the hysterectomy portion of the operation.

Vascular and Intestinal Injury

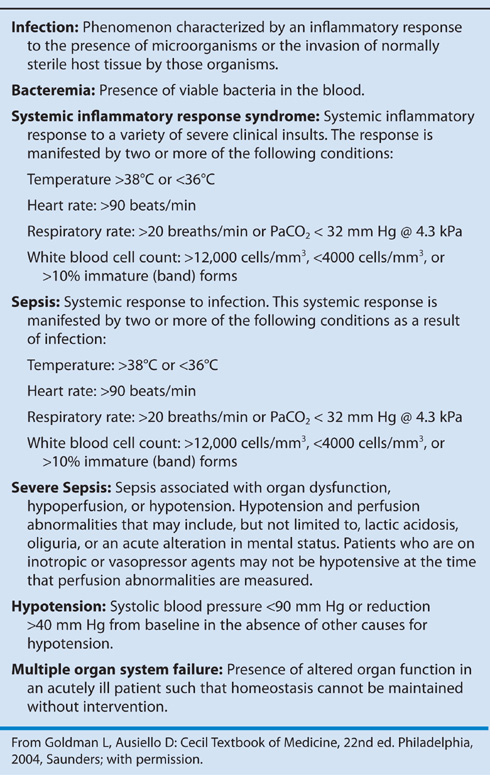

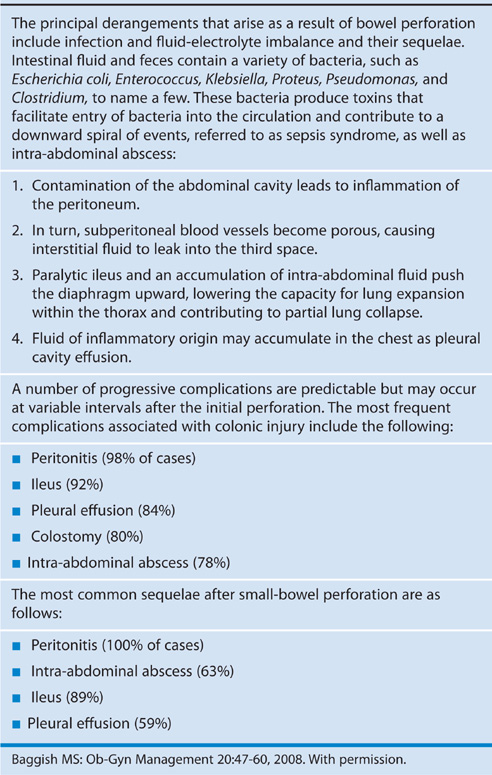

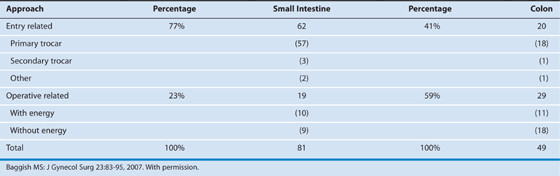

The two most serious laparoscopic complications are major vascular injury and intestinal damage. The former results in massive intra-abdominal hemorrhage and hypovolemic shock. This catastrophe must be managed in a timely, appropriate manner; otherwise, the patient will die (Fig. 122–1A through C). Small or large intestinal injury inevitably leads to immediate or delayed perforation (Fig. 122–2A, B). In some instances, significant damage to the bowel mesentery or directly to the blood vascular supply will result in ischemia followed by intestinal necrosis (Fig. 122–3A through D). As bowel contents spill into the abdominal cavity and then into the bloodstream, infection and sepsis follow. Sepsis syndrome is manifested by systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) (Tables 122–1 and 122–2). A cascade of events triggered by bacteremia and bacterial endotoxins and exotoxins eventuates in multiorgan failure. Necrotizing fasciitis may further complicate the picture in these cases. The condition progresses rapidly and is hallmarked by inordinate wound pain with cellulitis-like signs. Radiologic studies may show air within the abdominal wall (Fig. 122–3E, F). The bottom run of the downward spiral of events is septic shock (hypotension) and death. It is most convenient to subdivide these complications into those associated with the laparoscopic approach and those associated with the operative procedure (Table 122–3).

Laparoscopic Approach

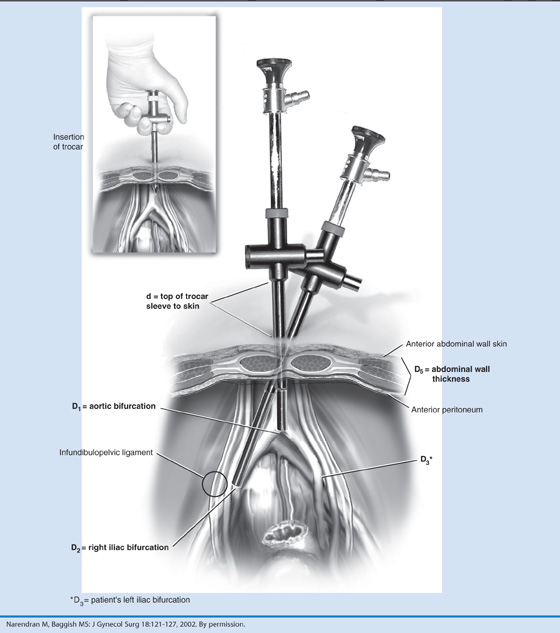

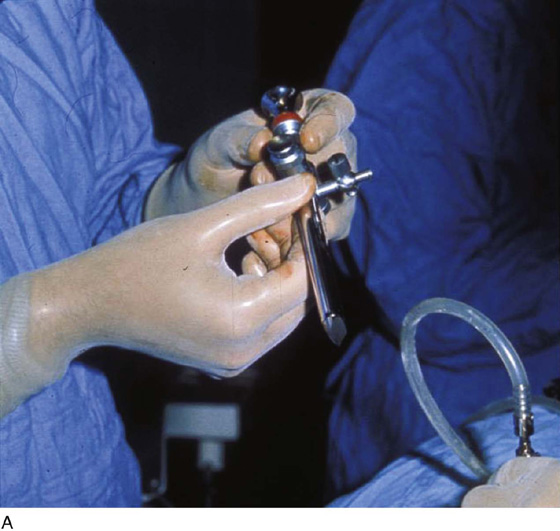

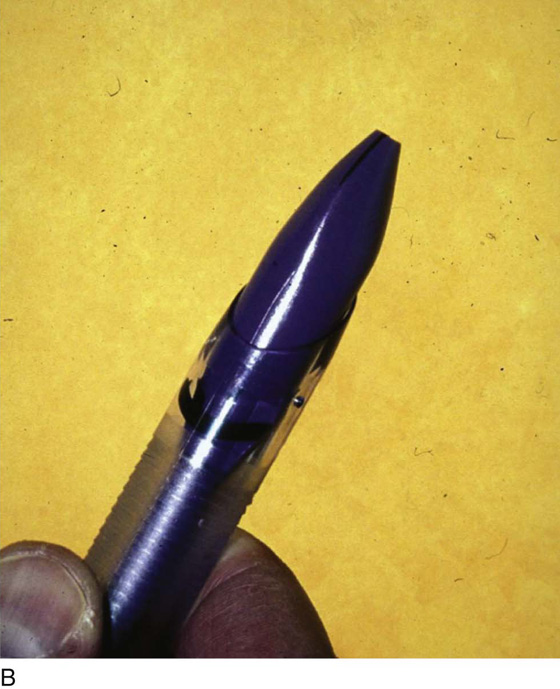

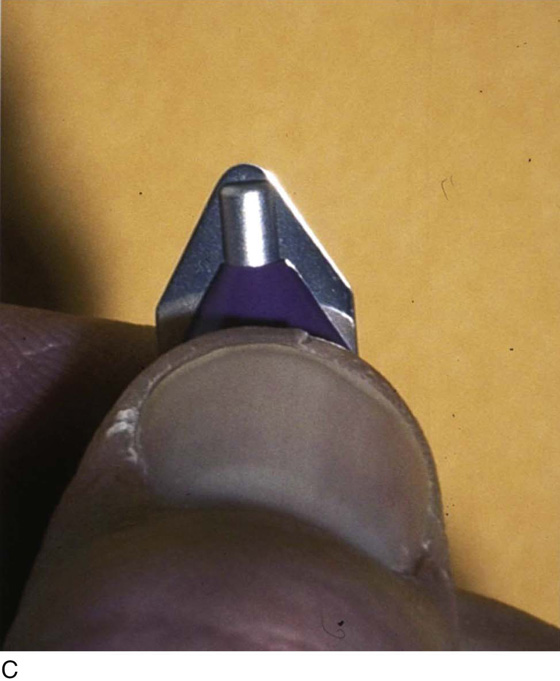

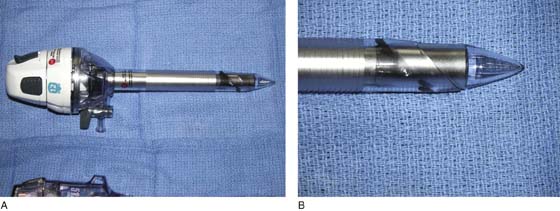

To gain access to the abdominal cavity, the laparoscope must be inserted through an appropriate sleeve or cannula (Fig. 122–4A through C). These generally range in size from 5 to 12 mm inner diameter. The sleeve is typically introduced directly by incision (usually infraumbilical) followed by dissection through the layers of tissue constituting the anterior abdominal wall. When the peritoneum is reached, it is tented up and incised or bluntly traversed. The sleeve is then introduced over a blunt trocar. This technique is described as open laparoscopy. An alternative technique introduces an inert gas (e.g., carbon dioxide) via a needle, which is thrust into the abdominal cavity. When sufficient gas has been introduced to create an adequate pneumoperitoneum, hallmarked by tympany on abdominal percussion, the sleeve is introduced into the peritoneal cavity over a sharp trocar. This is a de facto blind technique. Various alternations of the aforesaid technique have been described over the years, including a device that supposedly enables the operator to view each layer of the abdominal wall as the trocar is advanced (Fig. 122–5A, B).

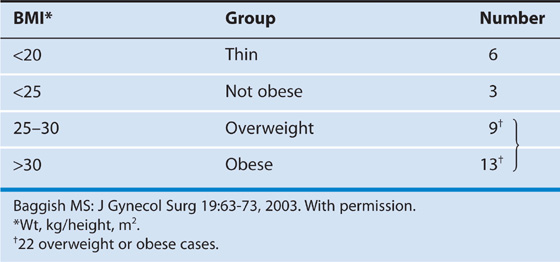

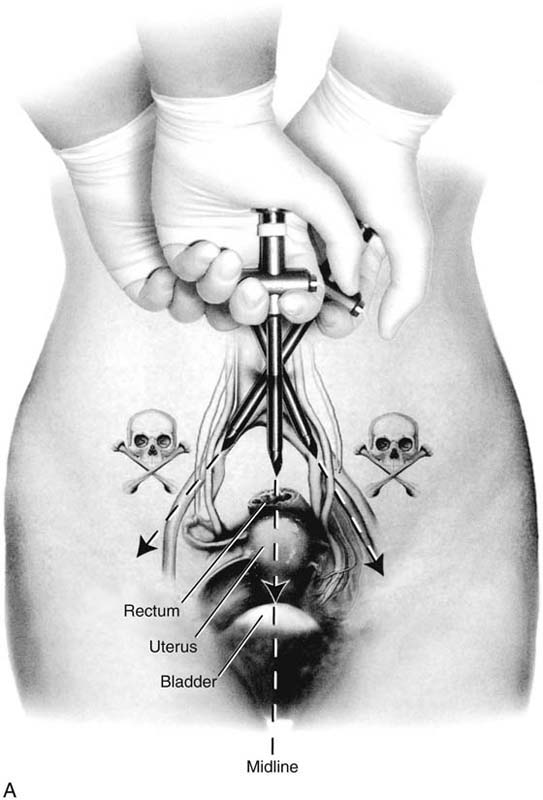

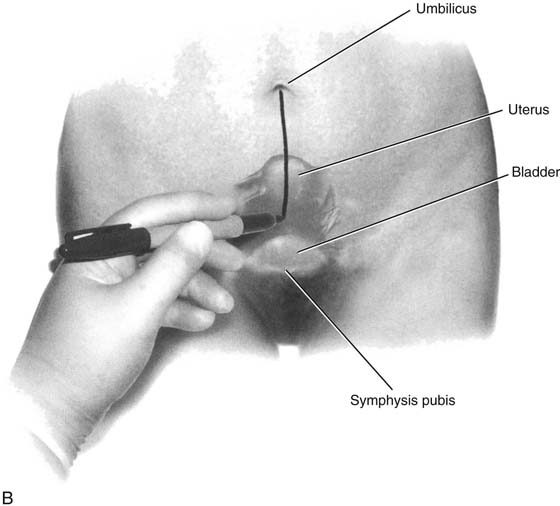

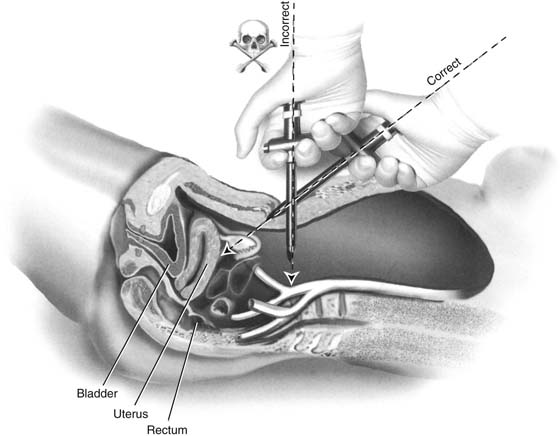

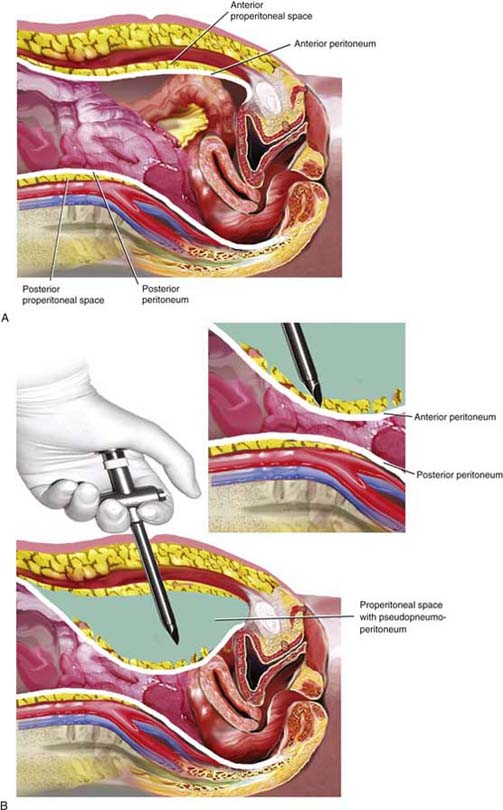

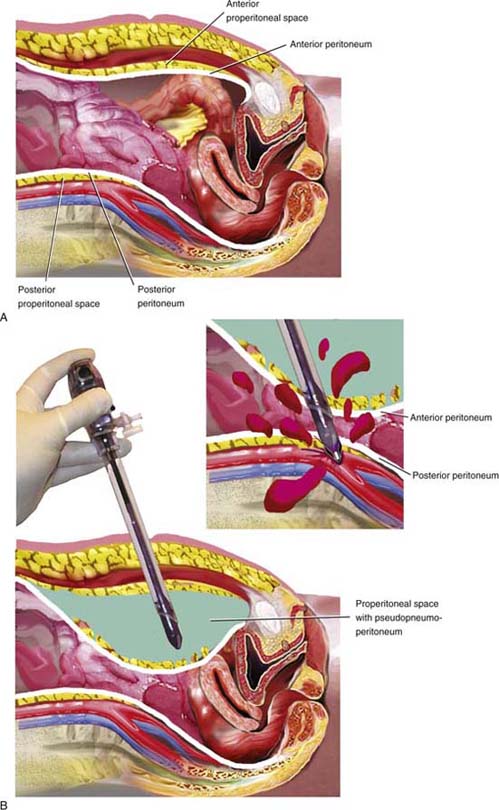

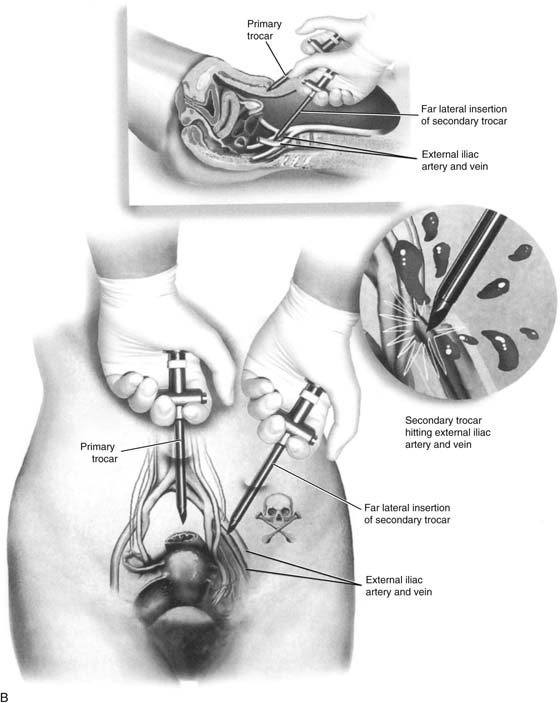

The basis for a “safe” trocar thrust as described in an earlier chapter in this section depends on two rules. First, the trocar must be thrust into them midline without deviation to the right or to the left of the midline (Fig. 122–6A, B). Second, the angle of entry of the trocar must be made at 45° to 60° (i.e., in the direction of the uterus) (Fig. 122–7). Deviation from these key provisions will ultimately lead to disastrous consequences for the patient and her physician. Individuals at the extremes of body mass index (i.e., the very lean and the obese) are particularly at risk for iatrogenic injury (Tables 122–4 and 122–5). The obese patient is the most high-risk patient, particularly if she has had prior intra-abdominal surgery and is likely to have adhesions (Tables 122–6). Trocar entry for these women may be difficult (Fig. 122–8 and 122–9).

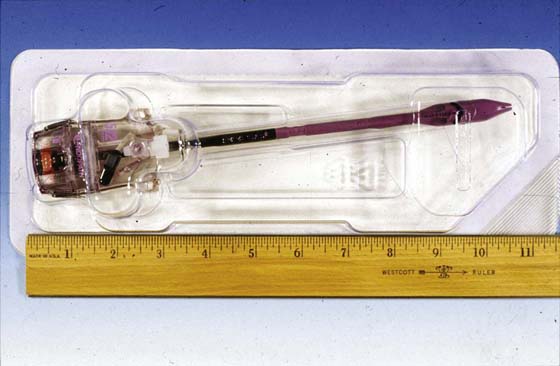

The surgeon should not resort to the use of extra long trocar devices (11 inches in length) (Fig. 122–10); these instruments are not necessary because a trocar of standardized length (8 inches in length) is more than adequate to gain entry (Fig. 122–11).

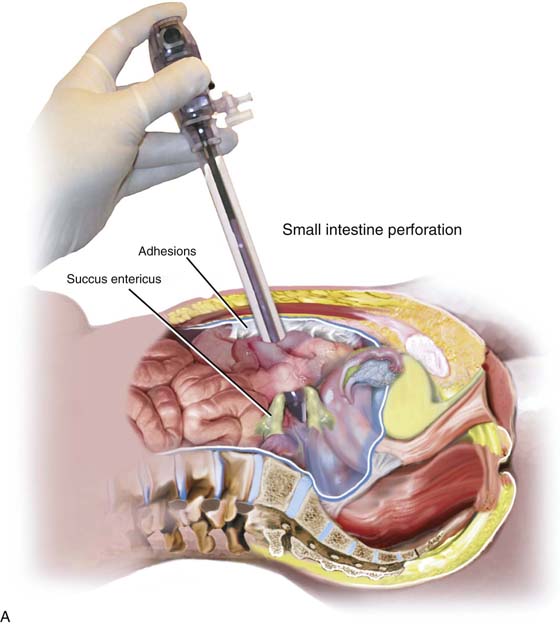

The surgeon is better advised to perform a laparotomy if a trocar of standard length is unable to provide entry into the abdominal cavity. A trocar that is thrust to the right or left of the midline may injure the iliac vessels or the vena cava (Fig. 122–12). A trocar that is thrust downward at 90° can and will injure the aorta or the left common iliac vein. Any primary trocar thrust has the potential for perforating the small intestines, whereas a deviant thrust may penetrate the large bowel (Fig. 122–13A). Because secondary trocars are placed under direct vision, injuries caused by these devices should not occur (Fig. 122–13B).

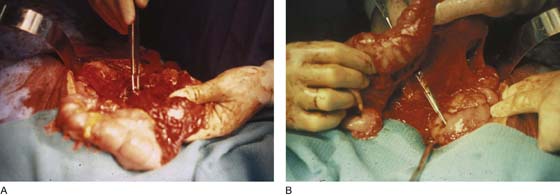

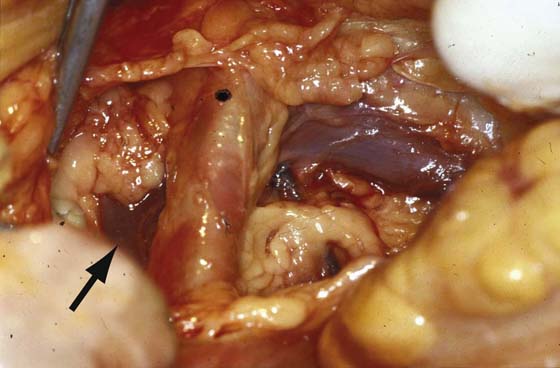

FIGURE 122–1 A. Autopsy of a young women who sustained a through and through trocar injury of the left common iliac artery and died of massive blood loss. The area below the forceps shows the laceration on the posterior wall of the artery. B. The probe passed by the coroner enters the posterior wall of the artery and exits through the anterior wall. Vascular clips can be seen on the left common iliac vein. C. The probe points to a laceration in the left common iliac vein. This was the fatal wound.

FIGURE 122–2 A. The forceps has been placed in a trocar wound of the omentum. B. The transverse colon has been elevated, permitting the scissors to trace the trajectory into a trocar-induced perforation of the duodenum.

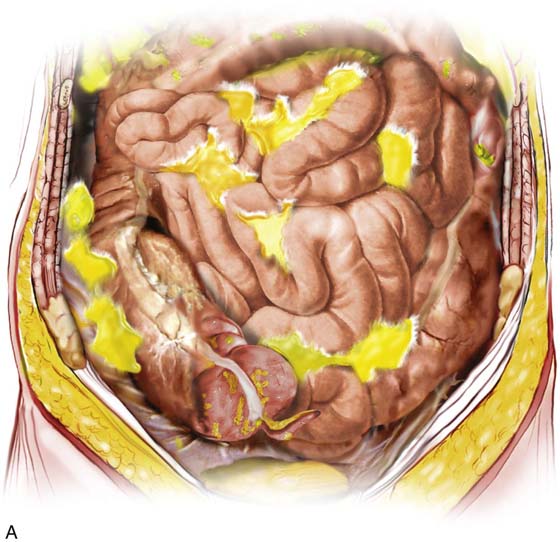

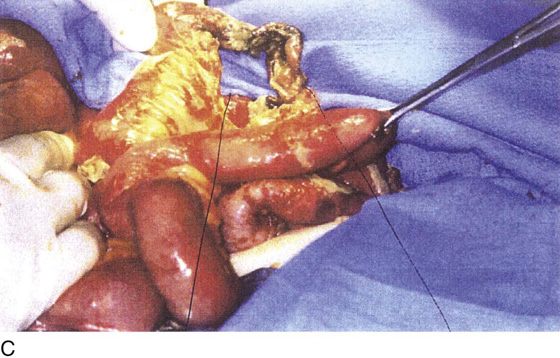

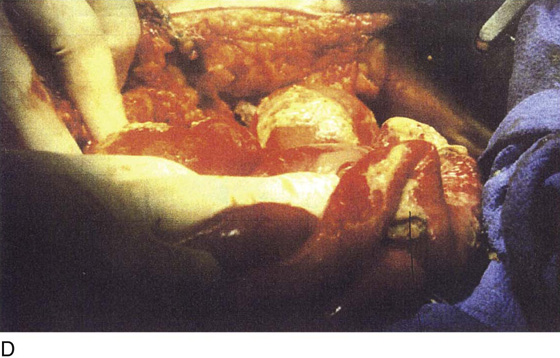

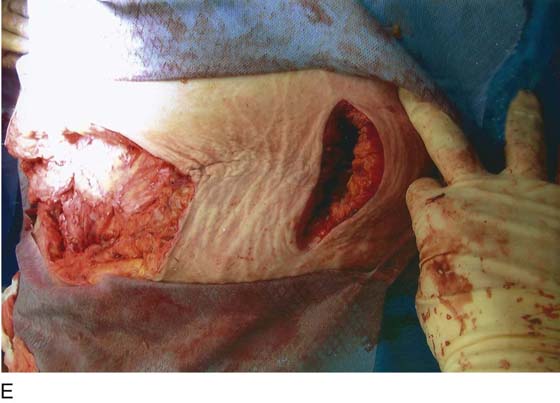

FIGURE 122–3 A. This 28-year-old para 3-0-0-3 underwent a postlaparoscopy emergency laparotomy. At the time of the laparotomy, the patient had extensive peritonitis and multiple small-bowel interloop abscess formations. Note the swollen, edematous small intestine. The patient also exhibited clinical signs of septic shock. B. The mesentery of the small intestine had been coagulated by plasma kinetic forceps and torn away from the intestine by blunt dissection during attempted adhesiolysis. Note the extensive ischemic and necrotic small bowel. C. Close-up at the necrotic segment of the small intestine shown in Fig. 122–3B. D. The small bowel is covered with fibrin secondary to extensive peritonitis. E. Necrotizing fasciitis is a byproduct of intestinal perforation and sepsis, particularly in obese patients. Group “A” streptococci or methicillin-resistant staphylococci rapidly spread along tissue planes while their toxins digest fat and fascia. This is clearly shown in this photo. The fat becomes grayish as the tissue undergoes cell death. F. Treatment consists of radical debridement of all dead or dying tissue. Frequent returns to the operating room are the rule before the infection is terminated. In this photo most of the fat of the anterior abdominal wall is gone, including the rectus sheath.

FIGURE 122–4 A. The 10-mm reusable trocar pictured here includes a pyramidal trocar fitted within the access sleeve. When properly sharp, this device can perforate bowel or one of the great retroperitoneal vessels. Frequently, the trocar is dull after multiple uses and is unlikely to create a major vessel injury. B. This figure illustrates the tip of a disposable trocar with the blade retracted (i.e., unarmed). C. In contrast to the trocar shown in Fig. 122–4A, the cutting blade of this disposable trocar (armed) is razor sharp. This device when misdirected can quite easily lacerate the wall of a major vessel.

FIGURE 122–5 A. This specialized trocar hypothetically allows one to view the layers of the abdominal wall as the device is thrust into the abdominal cavity. B. The conical tip of the trocar shown in Fig. 122–5A is pointed but not sharp. The clear color permits a semblance of vision of the abdominal wall tissues.

FIGURE 122–6 A. The trocar must be aimed at the midline to avoid injury to the iliac vessels. Deviation to the right or left places any and every patient at risk for major vessel injury. B. A convenient method to aid in the midline delivery of a trocar thrust is demonstrated here. A marking pen has been used to draw a straight line from the umbilicus to the symphysis pubis. (Baggish MS: J Gynecol Surg 19:63-73, 2003. By permission.)

FIGURE 122–7 Equal in importance for safe trocar entry is the angle for vectoring the trocar into the abdominal cavity. The correct angle is 45° to 60°. This changes the aim of the device in the direction of the uterus. A thrust at 90° will target the aorta or the left common iliac vein. (Baggish MS: J Gynecol Surg 19:63-73, 2003. By permission.)

FIGURE 122–8 A. Creation of a pneumoperitoneum in an obese woman may be difficult. Not infrequently, the pneumoperitoneum needle is placed into the peritoneal fat of the anterior abdominal wall. B. Gas inflated outside the peritoneal cavity creates a pseudopneumoperitoneum. A reusable trocar, if dull, will not penetrate the anterior peritoneum toward the posterior wall. A dull trocar usually will not injure the large retroperitoneal vessels.

FIGURE 122–9 A. A similar situation is shown here as in Fig. 122–8. B. In this case, a disposable trocar is depicted. Because the pseudopneumoperitoneal space is not capacious as compared with a true pneumoperitoneum, the shield fails to deploy, the trocar remains armed, and the sharp cutting blade penetrates into the posterior peritoneum, lacerating one of the large retroperitoneal vessels.

FIGURE 122–10 The long disposable trocar measures 11 inches in length and is a risky device. It should not be used because it increases the chance of major vascular injury.

FIGURE 122–11 The standard disposable trocar is 8 inches long and is capable of entering the abdominal cavity, even in obese women.

FIGURE 122–12 Close-up view of the mid and right retroperitoneum. The dot marks the right common iliac artery. The left common iliac vein crosses the midline from left to right over the L5 vertebral body. The arrow points to the right common iliac vein, which forms the inferior vena cava after it unites with the left common iliac vein just lateral to the proximal portion of the right common iliac artery.

FIGURE 122–13 A. This figure illustrates the uncommon circumstance of adhesions fixing a segment of small intestine to the anterior abdominal wall. The trocar penetrates the loop of bowel. The injury will not be detected unless the surgeon carefully observes as the sheath and the laparoscope are simultaneously withdrawn at the end of the procedure. B. Secondary trocars uncommonly cause major laparoscopic injuries because they are placed under direct vision. However, far lateral placement may cause injury to the external iliac vein or artery. (Baggish MS: J Gynecol Surg 19:63-73, 2003.)

TABLE 122–1  Definitions of Sepsis

Definitions of Sepsis

TABLE 122–3  One Hundred Thirty Cases of Intestinal Injury Associated With Laparoscopic Surgery

One Hundred Thirty Cases of Intestinal Injury Associated With Laparoscopic Surgery

TABLE 122–4  Patients (n = 31) With Major-Vessel Injury by Body Mass Index (BMI)*

Patients (n = 31) With Major-Vessel Injury by Body Mass Index (BMI)*

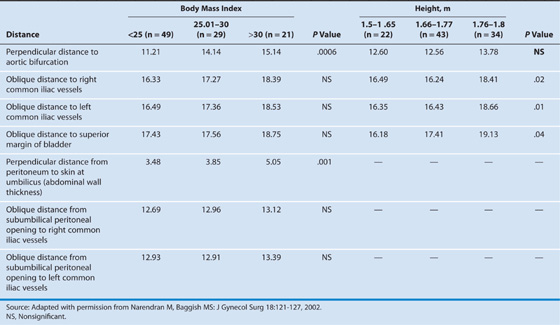

TABLE 122–5  Critical Measurements From Primary Trocar Entry Point to the Great Retroperitoneal Blood Vessels

Critical Measurements From Primary Trocar Entry Point to the Great Retroperitoneal Blood Vessels

TABLE 122–6  Mean Distances (cm) Between Umbilical Trocar Entry and Large Retroperitoneal Vessels

Mean Distances (cm) Between Umbilical Trocar Entry and Large Retroperitoneal Vessels

Operative Procedure

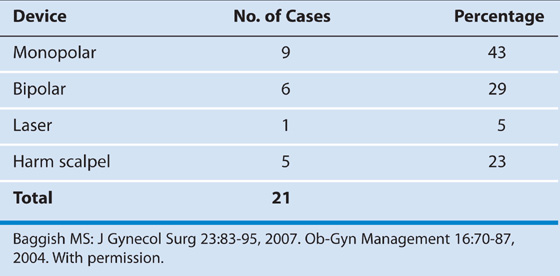

Injuries secondary to dissection are more likely to happen during laparoscopic operations than during laparotomy. Vision, particularly peripheral vision, is limited during laparoscopic procedures. Although the technique of bringing the laparoscope closer to the operative field magnifies the structures, the absence of a wide, panoramic, three-dimensional view limits depth perception and the ability to see surrounding structures. Finally, suturing and knot-tying are more difficult and more time consuming during laparoscopic procedures than during open techniques; thus energy devices (see Chapter 5) are more frequently employed during laparoscopy. High-power bipolar cutting and coagulating devices such as Plasma Kinetic Forceps (Gyrus ACMI, Southborough, Massachusetts) and LigaSure instruments (Covidien, Boulder, Colorado) are commonly used to obtain hemostasis; they do introduce the risk of thermal injury (Fig. 122–14A through D). Bipolar devices cause damage to structures by (1) spreading heat peripherally from the point of contact, and (2) directly grasping and cooking the wrong structure. Monopolar electrosurgical instruments are especially risky for high-frequency leaks, capacitative coupling, direct coupling, and insulation failure. Lasers and harmonic scalpel devices are also risky for creating thermal injuries beyond their intended target (Fig. 122–14E, Table 122–7). A seminal fact relates to minimally invasive operative procedures. The clinical pathway after laparoscopic surgery during the postoperative period is one of progressive clinical improvement. Each hour and each day should be marked by fewer symptoms and progressively improving signs. Deviation from the pathway should immediately signal the gynecologist to vigorously search for evidence of a complication related to his or her surgery (Fig. 122–15A, B). Early diagnosis of an injury will ameliorate the collateral damage. Failure to place a possible laparoscopic complication at the top of the differential diagnosis is an invitation to experience the most serious consequences (Tables 122–8, 122–9, and 122–10).

Ureteral Injury

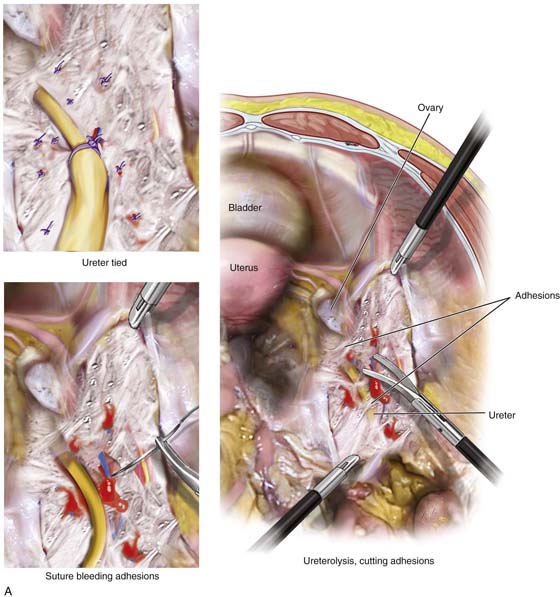

The third major complication associated with laparoscopic surgery is ureteral injury. The techniques used to avoid this type of injury are discussed in Chapter 37. Rarely are these complications caused by a trocar, although the ureter occasionally has been damaged as a collateral injury secondary to a major vessel or intestinal wound. Ureteral injuries generally will not result in mortality unless they are bilateral and neglected. However, an unrecognized ureteral obstruction or laceration may result in permanent kidney damage, leading to subsequent nephrectomy.

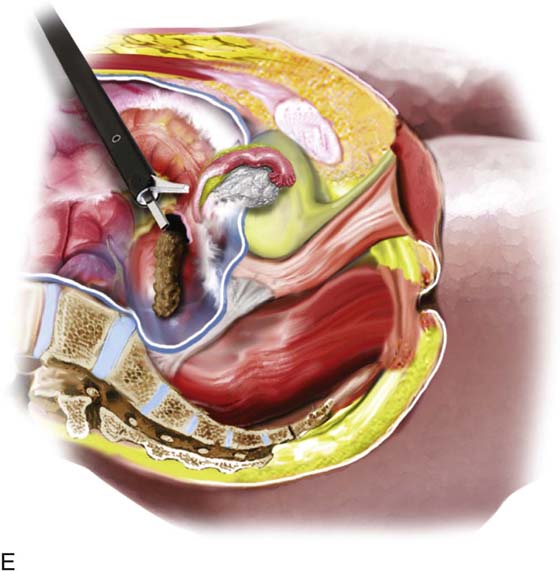

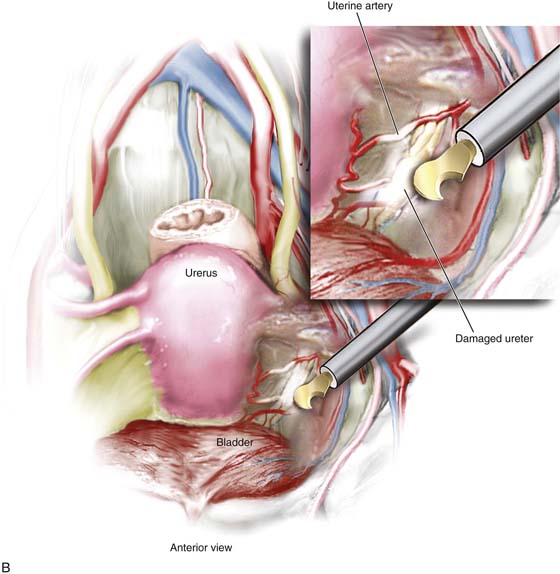

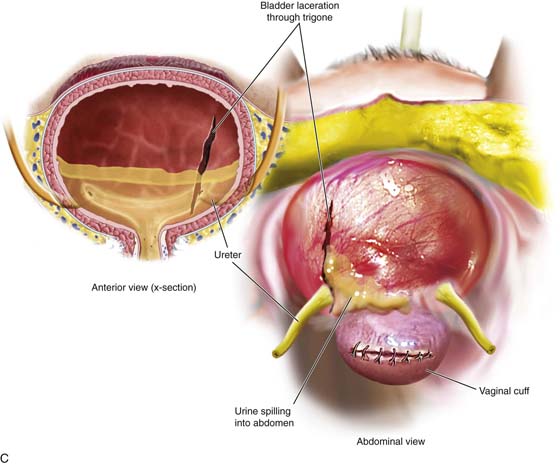

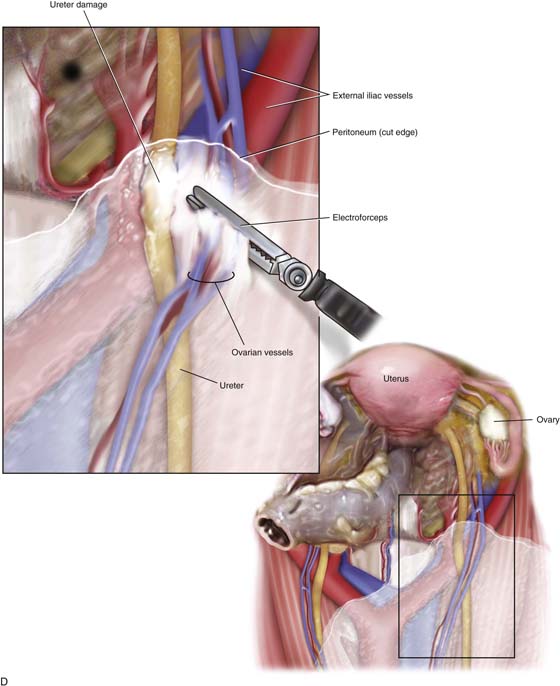

Ureteral injury is associated with the operative procedure and the sundry tools utilized for the purpose of hemostasis (Fig. 122–16A). Another major factor is related to lack of knowledge on the part of the surgeon relative to pelvic anatomy. Without this precise knowledge, surgeons are reluctant to explore the retroperitoneal space and isolate the ureter. As was noted in previous chapters, the ureter is vulnerable in three (Fig. 122–16B) principal locations: (1) where it crosses the common iliac vessels in concert with the ovarian blood supply, (2) where the uterine vessels cross over the ureter, and (3) where it enters the bladder, as well as within its intravesical course (Fig. 122–16C). Ancillary devices associated with ureteral injury include staplers, lasers, harmonic scalpels, and high-energy bipolar devices (LigaSure, plasma, kinetic forceps) (Fig. 122–16D). Less commonly, endo loops, sutures, and blunt dissection are associated with ureteral damage. The laparoscopic stapler is both wide and excessively long and accounts for an inordinately high number of ureteral injuries. This instrument typically obstructs and severs the ureter (Fig. 122–16E).

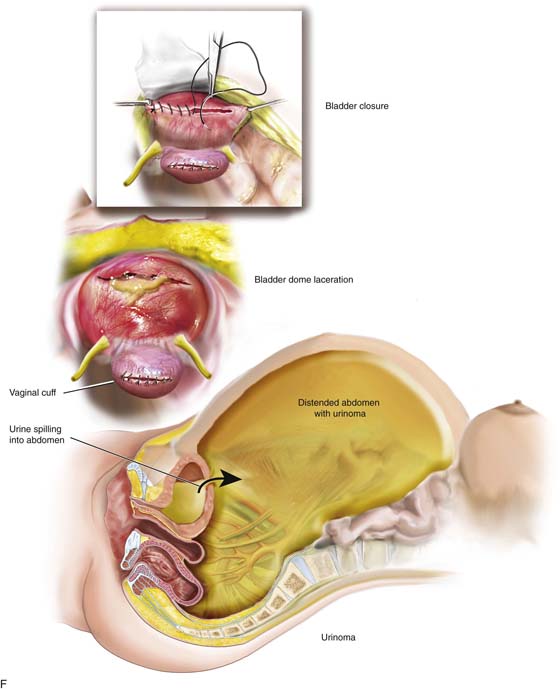

When a ureter or for that matter the bladder is lacerated or cut, urine spills into the abdominal cavity (Fig. 122–16F). The urine is partially absorbed via the peritoneum, leading to blood chemical derangements. The distention created by the accumulated fluid may be massive. A paracentesis should be performed to draw off the fluid, and a sample should always be sent to the laboratory for a creatine determination. An elevated creatine will cinch the diagnosis of urinoma.

Early recognition of ureteral obstruction or laceration is central or laceration is central to mitigate permanent kidney damage (Figs. 122–17 and 122–18). Symptoms of ureteral obstruction may range from severe abdominal and flank pain to minimal discomfort. Although any number of tests may be performed to enable a diagnosis to be made, the retrograde pyelogram is the most direct and important study (Fig. 122–19A through C). Once the diagnosis is secured, depending on the circumstances, treatment will take the form of passage of a stent or nephrostomy. Subsequent ureteroneocystotomy with or without psoas hitch will relieve the complication.

FIGURE 122–14 A. This high-power bipolar generator permits efficient bipolar coagulation and cutting. B. This contemporary multipurpose electrosurgical unit has monopolar, bipolar, and high output polar coagulation and cutting capability. C. This alligator-type Plasma Kinetic Forceps is utilized for hemostasis during robotic and major laparoscopic surgical procedures. D. This bipolar device (tripolar) coagulates tissue by extension of a sharp knife blade to instantly cut the thermally altered tissue. E. A harmonic cutting scissor-like device cuts into the sigmoid colon, creating a perforation and allowing fecal contents to spill into the peritoneal cavity.

FIGURE 122–15 A. The results of intestinal perforation include peritonitis and multiple-interloop abscess formation. B. A collateral injury is illustrated here. The deviant trocar thrust not only perforates the cecum but additionally lacerates the right common iliac artery.

FIGURE 122–16 A. The ureter is vulnerable to laceration or ligation during adhesiolysis. When adhesions are lysed, bleeding can ensue. Sutures placed to enable hemostasis can impinge upon or totally seal off the ureter if the latter is not secured. B. The harmonic scalpel creates hemostasis and cuts tissue. The hemostatic action generates heat through a variety of mechanisms, including friction. In the process of sealing and severing the uterine blood supply, the ureter may be thermally damaged as illustrated here. C. A bladder laceration that extends through the trigone is a very serious injury that requires expert management. Damage to the intravesical ureter or to the ureter at the ureterovesical junction must be ruled out. This will involve cystoscopic examination and retrograde pyelography. During the repair, ureteral stenting is recommended even if the ureter has not sustained injury. D. High-energy bipolar coagulation can and will create ureteral injury via thermal conduction through neighboring tissues. In the case illustrated here, a bipolar forceps coagulates the ovarian vessels, but heat spreads to encompass the nearby ureter, creating significant damage to that structure. E. The laparoscopic stapling device can cause ureteral injury when the instrument is applied across a vascular pedical without first securing the ureter. The long, broad jaws and staple cartridge do not permit discrete applications. F. This drawing illustrates a laceration in the superior portion of the bladder’s anterior wall (dome). The laceration was missed at the time of hysterectomy, and the patient developed a large urinoma. The laceration was subsequently repaired via a continuous through and through 2-0 chromic suture.

FIGURE 122–17 Ureteral injury is demonstrated by an IVP note that the left ureter is dilated. The left kidney shows hydronephrosis.

FIGURE 122–18 A further complication is demonstrated in this picture. The patient chronically seeped urine through a drain site situated in the left lower quadrant. When radiographic dye was instilled through the drain site, a ureterocutaneous fistula was diagnosed.

FIGURE 122–19 A. A retrograde urogram and intravenous pyelogram (IVP) were performed in this case. Note the normal right ureter. The left ureter shows disruption and extravasation of dye. The ureter was in fact severed. B. Retrograde urogram of the left ureter showing disruption and displacement of the ureter, as well as extravasation of dye. C. Close-up view of the left ureter shown in Fig. 122–19A and B.

TABLE 122–7  Energy Devices Associated With Intestinal Injury

Energy Devices Associated With Intestinal Injury

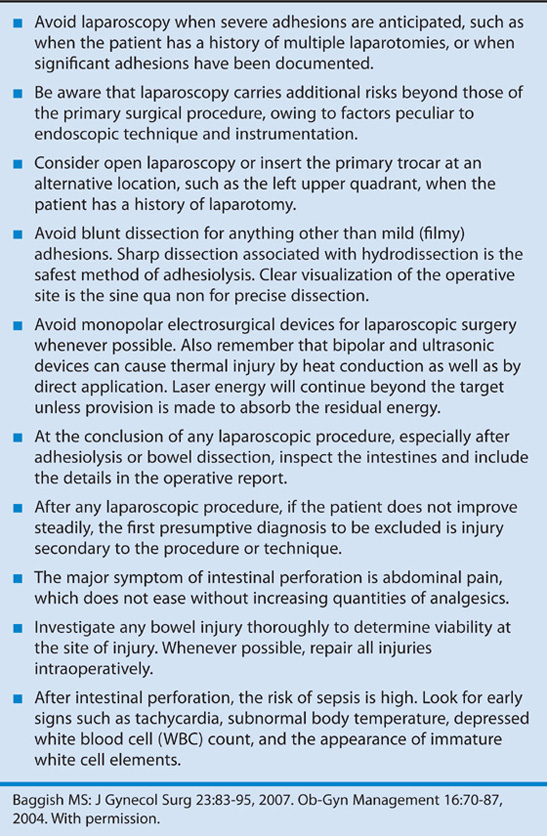

TABLE 122–8  Ten Ways to Lower the Risk of Intestinal Injury

Ten Ways to Lower the Risk of Intestinal Injury

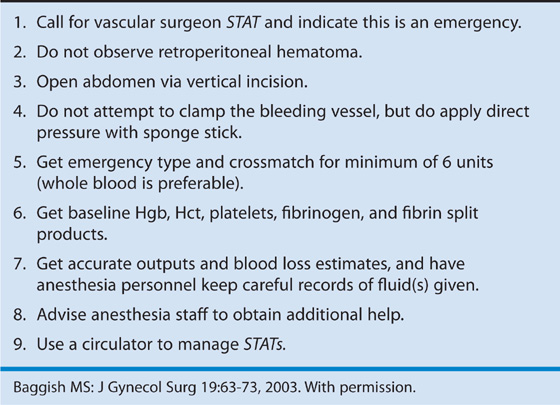

TABLE 122–9  Recommended Management for Gynecologists

Recommended Management for Gynecologists

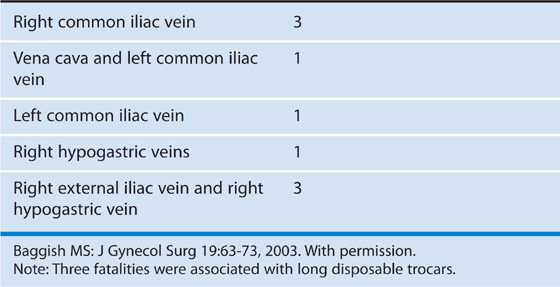

TABLE 122–10  Fatalities Always Involved Venous Injuries (7/31; 23%)

Fatalities Always Involved Venous Injuries (7/31; 23%)

Effects of Intestinal Perforation: Infection, Fluid-Electrolyte Imbalance, Sepsis Syndrome

Effects of Intestinal Perforation: Infection, Fluid-Electrolyte Imbalance, Sepsis Syndrome