M

Macewen, William (1847–1924). Eminent Scottish surgeon; Professor at Glasgow University, knighted in 1902. Advocated and practised tracheal intubation, usually oral, for laryngeal obstruction, e.g. due to diphtheria; he performed this by touch without anaesthetic. Was the first to advocate tracheal intubation instead of tracheotomy for head and neck surgery, in 1880. The tube was inserted before introduction of chloroform, and the patient allowed to breathe spontaneously. Packing around the tube achieved a seal.

Macintosh, Robert Reynolds (1897–1989). New Zealand-born anaesthetist, he became the first British Professor of Anaesthetics in Oxford in 1937. Lord Nuffield, a friend of Macintosh, had insisted that such a chair be set up as a precondition for endowing further chairs in Medicine, Surgery and Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Established Oxford as a centre for anaesthesia, and helped to establish anaesthesia as a medical specialty. Wrote books and articles about many aspects of local and general anaesthesia, and designed many pieces of equipment, including his laryngoscope, spray, endobronchial tube, vaporisers and devices for locating the epidural space. Also helped research the hazards of aviation and seafaring. Knighted in 1955, and received many other medals and awards.

McKesson, Elmer Isaac (1881–1935). US anaesthetist, practising in Toledo, Ohio. Founder and member of many US and international anaesthetic bodies. Also inventor and manufacturer of expiratory valves, pressure regulators, flowmeters, suction equipment, vaporisers and intermittent flow anaesthetic machines. A major proponent of the use of N2O in modern anaesthesia.

McMechan, Francis Hoeffer (1879–1939). US anaesthetist, practising in Cincinnati. A pioneer of the development of anaesthesia in the USA. Founded the American Association of Anesthetists in 1912, and instrumental in founding the National Anesthetic Research Society (subsequently the International Anesthesia Research Society) whose publication (which became Anesthesia and Analgesia) he edited.

Macrolides. Group of antibacterial drugs containing a lactam ring but distinct from β-lactams. Interfere with RNA-dependent protein synthesis. Includes erythromycin, azithromycin, clarithromycin and telithromycin. All have similar antibacterial activities (Gram-positive and some Gram-negative bacteria, mycoplasma, rickettsia and toxoplasma) but varying properties otherwise; thus the latter three drugs have longer durations of action than erythromycin and cause less nausea and vomiting.

Macrophage colony-stimulating factor, see Granulocyte colony-stimulating factor

Magill breathing system, see Anaesthetic breathing systems

Magill, Ivan Whiteside (1888–1986). Irish-born anaesthetist, responsible for much of the innovation in, and development of, modern anaesthesia. With Rowbotham in Sidcup after World War I, he developed endotracheal anaesthesia as an alternative to insufflation techniques, originally for facial plastic surgery. Introduced his own anaesthetic breathing system, forceps, laryngoscope and connectors, and developed blind nasal intubation. A pioneer of anaesthesia for thoracic surgery, he developed one-lung anaesthesia, endobronchial tubes and bronchial blockers. Also introduced bobbin flowmeters, portable anaesthetic apparatus and other equipment.

Co-founder of the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, he also helped establish the DA examination, the Faculty of Anaesthetists and the FFARCS examination. Worked at the Westminster and Brompton Hospitals, London. Knighted in 1960, and received many other medals and awards.

Magnesium. Largely intracellular ion, present mainly in bone (over 50%) and skeletal muscle (20%); the remainder is found in the heart, liver and other organs. 1% is in the ECF. Normal plasma levels: 0.75–1.05 mmol/l (although the value of measurement has been questioned, since most magnesium is intracellular). Deficiency is common in critical illness. Required for protein and nucleic acid synthesis, regulation of intracellular calcium and potassium, and many enzymatic reactions, including all those involving ATP synthesis/hydrolysis. Inhibits voltage-gated calcium channels, acting as a physiological antagonist; also an antagonist at NMDA receptors.

Herroeder S, Schonnher ME, De Hert SG, Hollman MW (2011). Anesthesiology; 114: 971–93

Magnesium sulphate. Drug with varied clinical indications, reflecting its numerous sites of action, e.g. non-competitive inhibition of phospholipase C-mediated calcium release; antagonism of NMDA receptors; inhibition of voltage-gated calcium channels and sodium/potassium pumps; and attenuation of catecholamine release from the adrenal glands. Its actions thus include neuronal/myocardial membrane stabilisation and bronchial and vascular smooth muscle relaxation. Magnesium chloride is also used.

as an anticonvulsant drug in pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Thought to act by reducing cerebral vasospasm seen in the condition. Also causes systemic vasodilatation, helping to lower BP. Superior to diazepam and phenytoin in preventing primary eclampsia, as well as preventing recurrence of seizures.

as an anticonvulsant drug in pre-eclampsia and eclampsia. Thought to act by reducing cerebral vasospasm seen in the condition. Also causes systemic vasodilatation, helping to lower BP. Superior to diazepam and phenytoin in preventing primary eclampsia, as well as preventing recurrence of seizures.

severe asthma resistant to conventional bronchodilator therapy.

severe asthma resistant to conventional bronchodilator therapy.

perioperative management of phaeochromocytoma.

perioperative management of phaeochromocytoma.

cardiac arrhythmias (e.g torsade de pointes), especially those caused by hypokalaemia.

cardiac arrhythmias (e.g torsade de pointes), especially those caused by hypokalaemia.

• Dosage: 2–4 g (8–16 mmol) iv over 5–15 min, followed by 1–2 g/h.

cardiac conduction defects, drowsiness, reduced tendon reflexes, muscle weakness, hypoventilation and cardiac arrest may occur with increasing hypermagnesaemia.

cardiac conduction defects, drowsiness, reduced tendon reflexes, muscle weakness, hypoventilation and cardiac arrest may occur with increasing hypermagnesaemia.

Overdosage may be treated with iv calcium.

Herroeder S, Schonnher ME, De Hert SG, Hollman MW (2011). Anesthesiology; 114: 971–93

Magnesium trisilicate. Particulate antacid, used in dyspepsia. Has been used to increase gastric pH preoperatively in patients at risk from aspiration of gastric contents, but may itself cause pneumonitis if inhaled. Has also been used to reduce risk of peptic ulceration on ICU, e.g. by hourly nasogastric administration to keep pH above 3–4.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI; Nuclear magnetic resonance, NMR). Imaging technique, particularly useful for investigating CNS, pelvic and musculoskeletal pathology, where tissue movement is minimal. By using gating techniques it can also be used in other parts of the body, including the chest; accurate measurements of the heart’s dimensions and movement have been obtained.

Involves placement of the patient within a powerful magnetic field, causing alignment of atoms with an odd number of protons or neutrons, e.g. hydrogen. Radiofrequency pulses are then applied, causing deflection of the atoms with absorption of energy. When each pulse stops, the atoms return to their aligned position, emitting energy as radiofrequency waves. Computer analysis of the emitted waves provides information about the chemical make-up of the tissue studied. MRI can provide graphic tissue slices in any plane, or may be used to analyse metabolic processes, e.g. distribution and alterations of intracellular phosphate (spectroscopy). So-called functional MRI (fMRI) techniques demonstrate regional differences in tissue oxygenation and cerebral blood flow. Interventional MRI involves surgery within the MRI suite to allow scanning during operative procedures.

• Problems and anaesthetic considerations:

sedation/anaesthesia may be required, especially in children or nervous adults, since the subject has to lie within a very small space and the scans are accompanied by loud knocking noises. Problems include those of radiology in general, in addition to the above. Scans originally took up to 2–3 h but are shorter with newer machines.

sedation/anaesthesia may be required, especially in children or nervous adults, since the subject has to lie within a very small space and the scans are accompanied by loud knocking noises. Problems include those of radiology in general, in addition to the above. Scans originally took up to 2–3 h but are shorter with newer machines.

Malaria. Tropical disease caused by the protozoan plasmodium (P. vivax, P. ovale or P. falciparum), and spread by the anopheles mosquito, which carries infected blood between individuals. Although not endemic in the UK, individual cases occur not uncommonly because of widespread air travel. Usual presentation is within 4 weeks of travel from an infected area, although onset may be delayed by many months. In milder forms, periodic release of the organism from the liver and reticuloendothelial system into the bloodstream causes relapsing fever, rigors and malaise (typically cycles of pyrexia lasting 3 days [tertian] or 4 days [quartan], or having no pattern [subtertian], depending on the infecting organism).

rigors, fever, vomiting, headache.

rigors, fever, vomiting, headache.

confusion, convulsions, coma. 80% of deaths result from cerebral malaria.

confusion, convulsions, coma. 80% of deaths result from cerebral malaria.

hypoglycaemia; thought to be caused by increased insulin secretion; it may also result from quinine therapy.

hypoglycaemia; thought to be caused by increased insulin secretion; it may also result from quinine therapy.

bronchopneumonia, acute lung injury, pulmonary oedema.

bronchopneumonia, acute lung injury, pulmonary oedema.

diarrhoea, endotoxaemia from bowel bacteria.

diarrhoea, endotoxaemia from bowel bacteria.

anaemia, thrombocytopenia, intravascular haemolysis, DIC. Diagnosis is made by examining blood films, or rarely, bone marrow, for parasites.

anaemia, thrombocytopenia, intravascular haemolysis, DIC. Diagnosis is made by examining blood films, or rarely, bone marrow, for parasites.

use of insect repellents, mosquito nets over beds, etc.

use of insect repellents, mosquito nets over beds, etc.

drug prophylaxis, e.g. mefloquine, doxycycline or malarone.

drug prophylaxis, e.g. mefloquine, doxycycline or malarone.

vaccination: a vaccine has been developed that can halve the infection rate.

vaccination: a vaccine has been developed that can halve the infection rate.

chloroquine and primaquine for mild infections.

chloroquine and primaquine for mild infections.

quinine; usually reserved for resistant organisms or severe falciparum infection.

quinine; usually reserved for resistant organisms or severe falciparum infection.

Malaria may be transmitted by blood transfusion; those with known infection or recent travel to an endemic area are therefore excluded from being donors.

Greenwood BM, Bojang K, Whitty CJM, Targett GAT (2005). Lancet; 365: 1487–98

– primary:

– local, e.g. pressure effects, ulceration, haemorrhage.

– systemic, e.g. anaemia, cachexia, susceptibility to infection, electrolyte disturbances (e.g. hypercalcaemia), endocrine effects (e.g. Cushing’s syndrome caused by bronchial carcinoma, carcinoid syndrome, myasthenic syndrome).

– metastatic, e.g. lung, liver, bone.

effects of previous treatment:

effects of previous treatment:

– surgery/radiotherapy, e.g. scarring, deformities.

– cytotoxic drugs, corticosteroids, opioid analgesic drugs and antidepressant drugs.

possible effects of anaesthesia on the immune system and cancer, e.g. administration of blood during bowel cancer resection may decrease survival.

possible effects of anaesthesia on the immune system and cancer, e.g. administration of blood during bowel cancer resection may decrease survival.

Malignant hyperthermia (MH). Condition first described by Denborough in 1961, consisting of increased temperature and rigidity during anaesthesia. Incidence is reported between 1:5000 and 1:200 000. Results from abnormal skeletal muscle contraction and increased metabolism affecting muscle and other tissues. Susceptibility shows autosomal dominant inheritance; in 50–70% of affected families the predisposing genetic loci are found on the long arm of chromosome 19, coding for the ryanodine/dihydropyridine receptor complex at the T-tubule/sarcoplasmic reticulum complex of striated muscle. This receptor regulates calcium flux in and out of the sarcoplasmic reticulum; this control is lost in MH, resulting in a massive influx of calcium leading to uncontrolled muscle contraction. MH susceptibility is also genetically related to central core disease, a rare muscular dystrophy. Several other gene mutations have been implicated, thus reducing the sensitivity of genetic analysis as a test for MH.

MH follows exposure to triggering agents, particularly the volatile anaesthetic agents and suxamethonium, although it is thought that a single dose of the latter by itself will not cause the syndrome. It may occur in patients who have had previously uneventful anaesthetics. MH may also be triggered by stress and strenuous exercise. Thus patients’ sensitivity to triggering agents may vary at different times. Reactions have been reported up to 11 h postoperatively.

• Features are related to muscle abnormality and hypermetabolism, but not all may be present:

sustained muscle contraction; results from breakage of the normal impulse/contraction sequence (excitation/contraction uncoupling) relating to abnormal calcium ion mobilisation, and is unrelieved by neuromuscular blocking drugs. Masseter spasm may be an early sign.

sustained muscle contraction; results from breakage of the normal impulse/contraction sequence (excitation/contraction uncoupling) relating to abnormal calcium ion mobilisation, and is unrelieved by neuromuscular blocking drugs. Masseter spasm may be an early sign.

muscle breakdown with release of potassium, myoglobin and muscle enzymes, e.g. creatine kinase. Hyperkalaemia may cause cardiac arrhythmias.

muscle breakdown with release of potassium, myoglobin and muscle enzymes, e.g. creatine kinase. Hyperkalaemia may cause cardiac arrhythmias.

increased O2 consumption, leading to cyanosis.

increased O2 consumption, leading to cyanosis.

increased CO2 production and hypercapnia. Hyperventilation may occur in the spontaneously breathing patient.

increased CO2 production and hypercapnia. Hyperventilation may occur in the spontaneously breathing patient.

rapidly increasing body temperature (e.g. > 0.5°C every 10 min) and sweating.

rapidly increasing body temperature (e.g. > 0.5°C every 10 min) and sweating.

dantrolene is the only available specific treatment. 1 mg/kg is given iv, repeated as required up to 10 mg/kg.

dantrolene is the only available specific treatment. 1 mg/kg is given iv, repeated as required up to 10 mg/kg.

– hyperventilation with 100% O2. Anaesthesia is maintained with TIVA.

– correction of acidosis with bicarbonate, according to the results of blood gas interpretation.

– cooling with cold iv fluids, fans, sponging and irrigation of body cavities. Other causes of hyperthermia should be considered.

– treatment of hyperkalaemia if severe.

– diuretic therapy (mannitol or furosemide) and urinary alkalinisation to reduce renal damage caused by myoglobin.

– treatment of any arrhythmias as they occur.

– corticosteroids (e.g. dexamethasone 4 mg) have been advocated.

– close monitoring in an ICU for 36–48 h postoperatively. Creatine kinase levels should be measured 12-hourly for 36–48 h, and the urine analysed for myoglobin.

– acute kidney injury and DIC are treated as necessary.

Treatment with dantrolene should be instituted as soon as the diagnosis is suspected. Arterial blood gas interpretation and measurement of plasma potassium should be performed early to detect acidosis and hyperkalaemia.

serum creatine kinase elevation and myoglobinuria are suggestive, but not diagnostic. The former is not reliable as a screening test. Creatine kinase and myoglobin may both increase after suxamethonium administration in normal patients.

serum creatine kinase elevation and myoglobinuria are suggestive, but not diagnostic. The former is not reliable as a screening test. Creatine kinase and myoglobin may both increase after suxamethonium administration in normal patients.

muscle biopsy may appear normal histologically.

muscle biopsy may appear normal histologically.

pretreatment with oral dantrolene is now thought to be unnecessary.

pretreatment with oral dantrolene is now thought to be unnecessary.

sedative premedication is sometimes given to reduce ‘stress’, but this is controversial.

sedative premedication is sometimes given to reduce ‘stress’, but this is controversial.

avoidance of known triggering agents: volatile agents and suxamethonium. N2O is considered safe. Many other drugs have been implicated at some time, but the above are the only definite triggers. TIVA is a useful technique. Local anaesthetic techniques may be used, but MH may still occur. All local anaesthetic agents are considered as safe as each other. Some would avoid phenothiazines and butyrophenones because of the neuroleptic malignant syndrome, but there is no evidence that the two conditions are related.

avoidance of known triggering agents: volatile agents and suxamethonium. N2O is considered safe. Many other drugs have been implicated at some time, but the above are the only definite triggers. TIVA is a useful technique. Local anaesthetic techniques may be used, but MH may still occur. All local anaesthetic agents are considered as safe as each other. Some would avoid phenothiazines and butyrophenones because of the neuroleptic malignant syndrome, but there is no evidence that the two conditions are related.

dantrolene and supportive treatments should be readily available.

dantrolene and supportive treatments should be readily available.

Mallampati score, see Intubation, difficult

Malnutrition. Nutrient deficiency, usually of several dietary components. Protein depletion with near-normal energy supply may lead to kwashiorkor, with hypoproteinaemia and oedema. Protein and energy depletion may lead to marasmus, with normal plasma protein concentration.

• Body reserves during total starvation under basal conditions:

carbohydrate: about 0.5 kg, mainly as liver and muscle glycogen; lasts < 1 day.

carbohydrate: about 0.5 kg, mainly as liver and muscle glycogen; lasts < 1 day.

protein: 4–6 kg, mainly as muscle; lasts 10–12 days.

protein: 4–6 kg, mainly as muscle; lasts 10–12 days.

fat: 12–15 kg, as adipose tissue; lasts 20–25 days.

fat: 12–15 kg, as adipose tissue; lasts 20–25 days.

Protein breakdown is reduced by even small amounts of glucose, possibly via resultant insulin secretion, inhibiting protein catabolism.

• Malnutrition is common to some degree in hospital patients. It may be associated with:

decreased intake, e.g. vomiting, malabsorption, anorexia, poor diet, nil-by-mouth orders.

decreased intake, e.g. vomiting, malabsorption, anorexia, poor diet, nil-by-mouth orders.

decreased utilisation, e.g. renal failure.

decreased utilisation, e.g. renal failure.

increased basal metabolic rate, e.g. trauma, burns, severe illness, pyrexia.

increased basal metabolic rate, e.g. trauma, burns, severe illness, pyrexia.

Thus common perioperatively, especially in severe chronic illness, GIT disease/surgery, alcoholics, the elderly and the mentally ill. May result in impaired wound healing, bedsores, increased susceptibility to infection, weakness, anaemia, hypoproteinaemia, electrolyte disturbances and dehydration, vitamin deficiency disorders and predisposition to hypothermia. Respiratory muscle weakness may predispose to respiratory complications.

Long-term nutrition, via enteral or parenteral routes, is thought to be beneficial preoperatively (at least 14 days). The place of short-term feeding is less certain. Progress may be monitored by weight or skin thickness measurements.

Managing Obstetric Emergencies and Trauma course (MOET course). Training programme, devised in 1998, designed for medical staff working within obstetrics, obstetric anaesthesia, and accident and emergency medicine. Similar to other acute life support courses in its systematic approach and structure.

Mandatory minute ventilation (MMV). Ventilatory mode used to assist weaning from ventilators. The required mandatory minute ventilation is preset, and the patient allowed to breathe spontaneously, with the ventilator making up any shortfall in minute volume. Thus with the patient breathing adequately, the ventilator is not required. However, a minute ventilation made up of rapid shallow breaths will also ‘satisfy’ the ventilator, despite alveolar ventilation being inadequate. In addition, not all ventilators allow spontaneous minute ventilation to exceed the preset one (extended mandatory minute ventilation; EMMV). Thus MMV is less popular than IMV.

Mandibular nerve blocks. Performed for facial and intraoral procedures.

• Anatomy: the mandibular division (V3) of the trigeminal nerve passes from the Gasserian ganglion through the foramen ovale.

motor nerves to the muscles of mastication and tensor muscles of the palate and eardrum.

motor nerves to the muscles of mastication and tensor muscles of the palate and eardrum.

sensory nerves (see Fig. 76; Gasserian ganglion block):

sensory nerves (see Fig. 76; Gasserian ganglion block):

– meningeal branch: passes through the foramen spinosum and supplies the adjacent dura.

– buccal nerve: supplies the skin and mucosa of the cheek.

– auriculotemporal nerve; supplies the anterior eardrum, ear canal, temporomandibular joint, cheek, temple, temporal scalp and parotid gland.

– lingual nerve: passes alongside the tongue to supply its anterior two-thirds, the floor of the mouth and lingual gum.

• Blocks:

mandibular: a needle is inserted at right angles to the skin between the coronoid and condylar processes, just above the bone. After contacting the pterygoid plate, it is redirected posteriorly until paraesthesiae are obtained, and 5 ml local anaesthetic agent injected (N.B. the pharynx lies 5 mm internally).

mandibular: a needle is inserted at right angles to the skin between the coronoid and condylar processes, just above the bone. After contacting the pterygoid plate, it is redirected posteriorly until paraesthesiae are obtained, and 5 ml local anaesthetic agent injected (N.B. the pharynx lies 5 mm internally).

1–2% lidocaine or prilocaine with adrenaline is most commonly used. Systemic absorption of adrenaline may cause symptoms, especially if high concentrations are used, e.g. 1:80 000. Immediate collapse following dental nerve blocks is thought to result from retrograde flow of solution via branches of the external carotid artery, reaching the internal carotid; perineural spread to the medulla has also been suggested.

See also, Gasserian ganglion block; Maxillary nerve blocks; Nose; Ophthalmic nerve blocks

Mandragora (Mandrake). Plant, supposedly human-shaped, thought to hold magic powers, including the ability to induce sleep and relieve pain. Contains hyoscine and similar alkaloids. According to legend, its scream on uprooting killed all who heard it, hence the supposedly ‘safe’ method of collection: a dog is tied to the plant at midnight, whilst its owner retreats to a safe distance with ears stopped with wax. The dog is enticed to run after food, pulling out the mandrake and dying in the process.

Mannitol. Plant-derived alcohol. An osmotic diuretic; it draws water from the extracellular and intracellular spaces into the vascular compartment, expanding the latter transiently. Not reabsorbed once filtered in the kidneys, it continues to be osmotically active in the urine, causing diuresis. Used mainly to reduce the risk of perioperative renal failure (e.g. during vascular surgery, surgery in obstructive jaundice) and to treat cerebral oedema. Efficacy in the latter depends on integrity of the blood–brain barrier that may be altered in neurological disease, although some benefit is derived from the systemic dehydration produced. Has also been used to lower intraocular pressure. It may also act as a free radical scavenger. Oral mannitol has been used (together with activated charcoal) as an osmotic agent to increase intestinal removal of poisons.

Temporarily increases cerebral blood flow; ICP may rise slightly before falling, especially after rapid injection. Excessive brain shrinkage in the elderly may rupture fragile subdural veins. A rebound increase in ICP may occur if treatment is prolonged, due to eventual passage of mannitol into cerebral cells; the effect is small after a single dose. A transient increase in vascular volume and CVP may cause cardiac failure in susceptible patients.

• Dosage: 0.25–2 g/kg by iv infusion of 10–20% solution over 20–30 min. Effects occur within 30 min, lasting 6 h. 0.25–0.5 g/kg may follow 6-hourly for 24 h, unless diuresis has not occurred, cardiovascular instability ensues or plasma osmolality exceeds 315 mosmol/kg.

Available as 10% and 20% solutions with osmolality 550 and 1100 mosmol/kg respectively.

Mann–Whitney rank sum test, see Statistical tests

Manslaughter. Unlawful killing of another person; a criminal charge (as opposed to the civil charge of negligence) that has been applied to anaesthetists in cases where the care provided was so poor as to constitute a reckless or grossly negligent act or omission. Examples have included fatal cardiac arrest following disconnection of the breathing system and inadequate immediate postoperative care.

MAO, see Monoamine oxidase

MAOIs, see Monoamine oxidase inhibitors

Mapleson classification of breathing systems, see Anaesthetic breathing systems

Marey’s law. Increased pressure in the aortic arch and carotid sinus causes bradycardia; decreased pressure causes tachycardia.

Marfan’s syndrome. Connective tissue disease, inherited as an autosomal dominant gene. Prevalence is 1:20 000.

tall stature, with long thin extremities. High arched palate. Joint dislocations, kyphoscoliosis, pes excavatum, inguinal and diaphragmatic herniae are common.

tall stature, with long thin extremities. High arched palate. Joint dislocations, kyphoscoliosis, pes excavatum, inguinal and diaphragmatic herniae are common.

cataracts and subluxation of the ocular lens (50%).

cataracts and subluxation of the ocular lens (50%).

– aortic regurgitation (< 90%).

– pneumothorax.

– tracheal intubation may be difficult (high arched palate).

Death usually results from aortic dilatation and its complications. Careful preoperative assessment for congenital heart disease and its sequelae is required.

Masks, see Facemasks; Oxygen therapy

Mass. Precise definitions vary, but include: the inertial resistance to movement of a body, and the amount of matter contained in a body. Under conditions of differing gravity, mass remains constant, whereas weight varies. SI unit is the kilogram.

Mass spectrometers may be used for on-line gas analysis during anaesthesia.

Masseter spasm. Increase in jaw tone occurring after suxamethonium. More common in children and after halothane induction, although the incidence is hard to determine because of diagnostic variability. A 1:100–1:3000 incidence has been reported, but is controversial. A protective effect of thiopental has been suggested. Spasm may represent a normal dose-related response to suxamethonium, but has been associated with MH susceptibility, especially if spasm is severe and prolonged, and associated with markedly raised serum creatine kinase and myoglobinuria. May also be seen in dystrophia myotonica following suxamethonium and acetylcholinesterase inhibitors.

Management of spasm is controversial: termination of anaesthesia and referral for muscle biopsy, treatment with dantrolene, and proceeding with caution have all been recommended.

Mast cells. Basophilic cells in connective and subcutaneous tissues, involved in inflammatory reactions and immune responses. Storage granules contain lytic enzymes (e.g. tryptase) and inflammatory mediators, e.g. histamine, kinins, heparin, 5-HT, hyaluronidase, leukotrienes, platelet aggregating and leucocyte chemotactic factors. Release is caused by: tissue injury; complement activation; drugs (e.g. atracurium); and cross-linkage of surface IgE molecules by antigen (i.e. true anaphylaxis). Also involved in presentation of antigen to lymphocytes. Occur in excess in mastocytosis, either in the circulation or as tissue infiltrates.

Maternal mortality, see Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths

Maxillofacial surgery. Anaesthesia may be required for elective surgery (e.g. for facial deformities, tumours) or because of facial trauma, infection or airway obstruction. General considerations are as for ENT, plastic and dental surgery, in particular problems of access, protection of the airway and the potential for long and bloody surgery. Bradycardia may occur during procedures around the face (see Oculocardiac reflex).

Maxillary nerve blocks. Performed for facial and intraoral procedures.

• Anatomy: the maxillary division (V2) of the trigeminal nerve passes from the Gasserian ganglion through the foramen rotundum into the pterygopalatine fossa, dividing into sensory branches and continuing as the infraorbital nerve (see Fig. 76; Gasserian ganglion block). Branches:

via the pterygopalatine ganglion to the nose, nasopharynx and palate via nasal, nasopalatine, greater and lesser palatine and pharyngeal nerves.

via the pterygopalatine ganglion to the nose, nasopharynx and palate via nasal, nasopalatine, greater and lesser palatine and pharyngeal nerves.

greater palatine: supplies the posterior hard palate and palatal gingiva of adjacent teeth.

greater palatine: supplies the posterior hard palate and palatal gingiva of adjacent teeth.

zygomatic nerve: supplies the temple, cheek and lateral eye.

zygomatic nerve: supplies the temple, cheek and lateral eye.

posterior superior alveolar nerve: supplies the molar/premolar teeth.

posterior superior alveolar nerve: supplies the molar/premolar teeth.

• Blocks:

maxillary nerve: a needle is inserted extraorally 0.5 cm below the midpoint of the zygoma and directed medially until bone is contacted. It is redirected anteriorly and advanced a further 1 cm, anterior to the lateral pterygoid plate. 3–4 ml local anaesthetic agent is injected. May also be blocked via the intraoral route: the needle is inserted behind the posterior border of the zygoma and directed upwards, medially and posteriorly 3 cm. Up to 5 ml solution is injected within the pterygopalatine fossa.

maxillary nerve: a needle is inserted extraorally 0.5 cm below the midpoint of the zygoma and directed medially until bone is contacted. It is redirected anteriorly and advanced a further 1 cm, anterior to the lateral pterygoid plate. 3–4 ml local anaesthetic agent is injected. May also be blocked via the intraoral route: the needle is inserted behind the posterior border of the zygoma and directed upwards, medially and posteriorly 3 cm. Up to 5 ml solution is injected within the pterygopalatine fossa.

for the Cadwell–Luc approach, the mucosa and periosteum above the upper premolars may be infiltrated with 5–10 ml solution, to block branches of the anterior superior alveolar nerve. Topical application of, e.g. lidocaine may assist the block. Further solution may be injected into the mucosa of the maxillary sinus once opened. Alternatively, maxillary or infraorbital nerve blocks may be performed.

for the Cadwell–Luc approach, the mucosa and periosteum above the upper premolars may be infiltrated with 5–10 ml solution, to block branches of the anterior superior alveolar nerve. Topical application of, e.g. lidocaine may assist the block. Further solution may be injected into the mucosa of the maxillary sinus once opened. Alternatively, maxillary or infraorbital nerve blocks may be performed.

1–2% lidocaine or prilocaine with adrenaline is most commonly used. Systemic absorption of adrenaline may cause symptoms, especially if high concentrations are used, e.g. 1:80 000.

[George Caldwell (1834–1918), US ENT surgeon; Henri Luc (1855–1925), French ENT surgeon]

Maximal breathing capacity, see Maximal voluntary ventilation

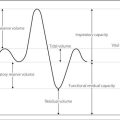

Maximal voluntary ventilation (Maximal breathing capacity). Maximal minute volume of air able to be breathed, measured over 15 s. Normally about 120–150 l/min. Equals approximately 35 × FEV1. Rarely used, since very tiring to perform.

MCH/MCHC/MCV. Mean cell haemoglobin/Mean cell haemoglobin concentration/Mean cell volume, see Erythrocytes

MEA syndrome, see Multiple endocrine adenomatosis

Population mean is denoted by µ; sample mean by  .

.

Means of more than one sample group may be compared using statistical tests.

See also, Median; Mode; Standard error of mean; Statistical frequency distributions; Statistics

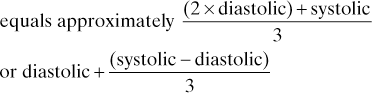

Mean arterial pressure (MAP). Average arterial BP throughout the cardiac cycle. The area contained within the arterial waveform pressure trace above MAP equals the area below it.

Mechanocardiography. Recording of the mechanical pulsations of the CVS; includes tracings of the JVP and venous waveform, arterial waveform and recordings at the apex using an externally applied transducer. Has been used to investigate cardiovascular disease, especially valvular disease, and to determine systolic time intervals.

Median. Expression of the central tendency of a set of measurements or observations.

Half the population lies above it, half below. Equals the mean for a normal distribution.

Median nerve (C6–T1). Arises from the medial and lateral cords of the brachial plexus in the lower axilla, lateral to the axillary artery. Passes down the front of the arm to the antecubital fossa, first lateral to the brachial artery, then crossing it anteriorly at mid/upper arm to lie medially. Entering the forearm, it crosses the ulnar artery anteriorly, separated from it by pronator teres’s deep head. Passes between flexor digitorum superficialis and profundus; at the wrist it lies between the tendons of palmaris longus (medially) and flexor carpi radialis (laterally).

May be blocked at the brachial plexus, elbow, forearm and wrist.

See also, Brachial plexus block; Elbow, nerve blocks; Wrist, nerve blocks.

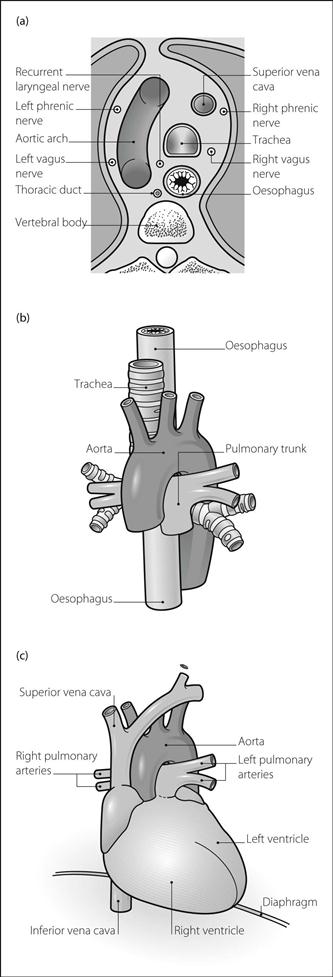

Mediastinum. Region of the thorax between the two pleural sacs. It is in contact with the diaphragm inferiorly, and continuous with the tissues of the neck superiorly. Lies between the vertebral column posteriorly and sternum anteriorly. Contains the heart, great vessels, trachea, oesophagus, thoracic duct, vagi, phrenic and recurrent laryngeal nerves, sympathetic trunk, thymus and lymph nodes (Fig. 104).

superior mediastinum: above a horizontal line level with T4/5 and the angle of Louis.

superior mediastinum: above a horizontal line level with T4/5 and the angle of Louis.

inferior mediastinum: below this line. Composed of anterior (between heart and sternum), middle (containing pericardium and contents) and posterior (between heart and vertebrae) portions.

inferior mediastinum: below this line. Composed of anterior (between heart and sternum), middle (containing pericardium and contents) and posterior (between heart and vertebrae) portions.

Thus mediastinal enlargement may be caused by:

enlargement of any of the above constituent structures (central).

enlargement of any of the above constituent structures (central).

spinal and vertebral masses (posterior).

spinal and vertebral masses (posterior).

thymic, thyroid, teratoma and dermoid tumours (anterior). Tumours (e.g. bronchial carcinoma) may involve local structures within the mediastinum, e.g. recurrent laryngeal or phrenic nerves, pericardium. Bleeding from the aorta following chest trauma or dissection may cause widening of the superior mediastinum.

thymic, thyroid, teratoma and dermoid tumours (anterior). Tumours (e.g. bronchial carcinoma) may involve local structures within the mediastinum, e.g. recurrent laryngeal or phrenic nerves, pericardium. Bleeding from the aorta following chest trauma or dissection may cause widening of the superior mediastinum.

• Main anaesthetic considerations:

preoperative state, e.g. related to the primary malignancy. Tracheal compression and airway obstruction, superior vena caval obstruction, phrenic and recurrent laryngeal nerve involvement and drug/radiotherapy effects may be present.

preoperative state, e.g. related to the primary malignancy. Tracheal compression and airway obstruction, superior vena caval obstruction, phrenic and recurrent laryngeal nerve involvement and drug/radiotherapy effects may be present.

classically, induction of anaesthesia is inhalational, but some advocate iv induction. Reinforced tracheal/bronchial tubes are often preferable.

classically, induction of anaesthesia is inhalational, but some advocate iv induction. Reinforced tracheal/bronchial tubes are often preferable.

one-lung anaesthesia and even extracorporeal circulation may be required during resection.

one-lung anaesthesia and even extracorporeal circulation may be required during resection.

Medical emergency team (MET). Team consisting of medical and nursing staff skilled in resuscitation (in its broadest sense) responding to standardised calling criteria, including abnormal physiological variables (e.g. systolic BP < 90 mmHg), specific conditions or ‘any time urgent medical assistance is required’. May replace existing cardiac arrest teams on the basis that prevention of cardiac arrest or severe physiological deterioration is likely to have a better outcome than treatment applied after cardiac arrest. Its effect on preventing cardiac arrest, decreasing ICU admission and improving mortality has not been proven.

Lee A, Bishop G, Hillman KM, Daffurn K (1995). Anaesth Intens Care; 23: 183–6

See also, Acute life-threatening events – recognition and treatment; Outreach team; Postoperative care team

Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). UK government agency formed in 2003 from the Medicines Control Agency and Medical Devices Agency. Responsible for regulating medicines and medical devices and ensuring their safety, via approval/regulation/monitoring of clinical trials, reporting/investigating adverse drug reactions and licensing/testing medicinal products and devices.

Medicolegal aspects of anaesthesia. In the UK, these usually concern matters of civil law, e.g. negligence, breach of contract or battery; proof must be according to ‘balance of probabilities’. Criminal law is involved less commonly, e.g. involving murder or manslaughter due to criminal neglect or reckless disregard of clinical duties; proof must be ‘beyond reasonable doubt’.

Anaesthesia is considered a high-risk specialty because of common minor claims (e.g. damage to teeth) and very expensive major claims.

perioperative deaths: those occurring within 24 h of anaesthesia are reported to the coroner, who may order an inquiry or inquest, although the time interval is not specified by law. Once reported, organs may not be harvested for transplantation without the coroner’s permission.

perioperative deaths: those occurring within 24 h of anaesthesia are reported to the coroner, who may order an inquiry or inquest, although the time interval is not specified by law. Once reported, organs may not be harvested for transplantation without the coroner’s permission.

fitness to practise: investigated by a committee of the General Medical Council (GMC) that regulates licensing to practise medicine in the UK; although not a civil court, the process may be broadly similar.

fitness to practise: investigated by a committee of the General Medical Council (GMC) that regulates licensing to practise medicine in the UK; although not a civil court, the process may be broadly similar.

Similar considerations apply to ICU, although claims arising from ICU itself are less common; however ICU may be required for critical illness arising from negligent practice. Specific ICU issues with medicolegal implications include competence (whether the patients are able to make their own decisions), non-provision of life-sustaining treatment or withdrawal of treatment (justified if it is in the patient’s best interests to be allowed to die) and brainstem death. The need for attention to detail and proper record-keeping is just as important as in general anaesthetic practice.

In general, risks are reduced by: checking of anaesthetic equipment; use of the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist; adequate preoperative assessment and preparation (including warning patients of risks); consultation with senior colleagues when appropriate; adherence to generally accepted techniques, including adequate monitoring; careful writing of clinical notes and anaesthetic record-keeping, with copies kept for later use; and full and honest explanation with patients and/or relatives when anything goes wrong.

See also, Abuse of anaesthetic agents; Anaesthetic morbidity and mortality; Ethics; Sick doctor scheme

Meglitinides. Oral hypoglycaemic drugs used in the management of diabetes mellitus. Stimulate insulin release from the functioning β cells of the pancreas. Taken just before meals. Two available agents are nateglinide and repaglinide; the former is only licensed for use in combination with metformin. Common side effects include headache and upper respiratory tract infections.

Melatonin. Hormone synthesised and released by the pineal gland. Formed from the amino acid tryptophan, its formation is promoted by darkness and inhibited by light. Actions include control of circadian rhythms, modulation of seasonal changes in physiology, timing of puberty and thermoregulation. Its function of regulating sleep has resulted in its use in combating sleep deprivation in ICU patients.

Membrane potential. Electrical potential difference across a cell membrane, present in almost all living eukaryotic cells. Results from the differential distribution of charged particles across cell membranes. The distribution of each particle is determined by its permeability across the membrane, the distribution of other particles (e.g. Donnan effect) and active transport systems, e.g. sodium/potassium pump. Membranes are impermeable to proteins (negatively charged), which thus remain intracellular; membranes are poorly permeable to sodium ions and moderately permeable to chloride and potassium ions.

Electrochemical gradients exist across the cell membrane for each ion; the membrane potential at equilibrium for each is calculated by the Nernst equation. Membrane potentials at given intracellular/extracellular concentrations of sodium, chloride and potassium ions together are calculated by the Goldman constant-field equation.

Changes in membrane permeability may alter, or be altered by, membrane potential, e.g. during action potentials.

Membranes. Biological membranes share certain features:

resting membrane potential is created by differential permeability for certain ions, together with active transport pumps. Most membranes are relatively permeable to chloride and potassium ions, less so to sodium ions, and relatively impermeable to proteins and anions. Non-charged substances (e.g. CO2 and non-ionised drugs) are able to cross freely, as is water.

resting membrane potential is created by differential permeability for certain ions, together with active transport pumps. Most membranes are relatively permeable to chloride and potassium ions, less so to sodium ions, and relatively impermeable to proteins and anions. Non-charged substances (e.g. CO2 and non-ionised drugs) are able to cross freely, as is water.

function of cells is dependent on the features of their membrane proteins, which may be altered by electrical signals or chemicals, e.g. drugs, hormones, neurotransmitters. The action of anaesthetic agents is thought to involve alteration of membrane configuration within the nervous system.

function of cells is dependent on the features of their membrane proteins, which may be altered by electrical signals or chemicals, e.g. drugs, hormones, neurotransmitters. The action of anaesthetic agents is thought to involve alteration of membrane configuration within the nervous system.

Mendelson’s syndrome, see Aspiration pneumonitis

Meninges. Tissue layers surrounding the brain and spinal cord, composed of:

pia mater: delicate vascular layer, closely adherent to the brain and cord, following their surfaces into clefts, sulci, etc. Surrounded by CSF within the arachnoid. Thin projections of the latter cross the subarachnoid space to the pia. Blood vessels lie within the space.

pia mater: delicate vascular layer, closely adherent to the brain and cord, following their surfaces into clefts, sulci, etc. Surrounded by CSF within the arachnoid. Thin projections of the latter cross the subarachnoid space to the pia. Blood vessels lie within the space.

Within the vertebral canal, the denticulate ligament passes laterally from the pia along its length and attaches at intervals to the dura. The subarachnoid septum lies posteriorly, attaching to the arachnoid intermittently. The pia terminates as the filum terminale, which passes through the caudal end of the dural sac and attaches to the coccyx.

dura mater: composed of two fibrous layers: the outer is adherent to the periosteal lining of the skull; the inner attaches to the outer but is separated by venous sinuses. The inner layer forms sheets within the skull:

dura mater: composed of two fibrous layers: the outer is adherent to the periosteal lining of the skull; the inner attaches to the outer but is separated by venous sinuses. The inner layer forms sheets within the skull:

The dura also forms two layers within the vertebral canal: the external adherent to the inner periostium of the vertebrae and the internal lying against the outer surface of the arachnoid. The space between the two dura layers is the epidural space. Projections and fibrous bands are present within the epidural space, especially in the midline. Dura projects intermittently to the posterior longitudinal ligament of the vertebrae, especially lumbar. Dura ends at about S2.

All layers donate a thin covering ‘sleeve’ to cranial nerves and spinal nerves as they leave the CNS. These dural cuffs, which contain CSF, may accompany spinal nerves through the intravertebral foramina.

Meningitis. Inflammation of the meninges. Usually infective:

viral: usually coxsackie, echo, herpes and mumps viruses. Usually has good prognosis, unless associated with generalised encephalitis.

viral: usually coxsackie, echo, herpes and mumps viruses. Usually has good prognosis, unless associated with generalised encephalitis.

bacterial: Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcal meningitis), Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcal meningitis) and Haemophilus influenzae are the most common organisms. Mortalilty is high unless treated; adhesions, hydrocephalus and cranial nerve damage are still possible after treatment.

bacterial: Neisseria meningitidis (meningococcal meningitis), Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcal meningitis) and Haemophilus influenzae are the most common organisms. Mortalilty is high unless treated; adhesions, hydrocephalus and cranial nerve damage are still possible after treatment.

others, e.g. TB, listeria, fungi.

others, e.g. TB, listeria, fungi.

Aseptic meningitis may also occur; it may be caused by malignant infiltration, chemical irritation (e.g. alcoholic solutions used to clean the skin before lumbar puncture) and occasionally drugs (e.g. NSAIDs, H2 receptor antagonists).

fever, nausea, vomiting, headache, photophobia, convulsions, coma.

fever, nausea, vomiting, headache, photophobia, convulsions, coma.

cranial nerve lesions or signs of cerebral oedema may be present.

cranial nerve lesions or signs of cerebral oedema may be present.

may be associated with systemic involvement, e.g. effects of severe sepsis in meningococcal disease.

may be associated with systemic involvement, e.g. effects of severe sepsis in meningococcal disease.

CT scan is usually required to exclude space-occupying lesions and raised ICP before lumbar puncture.

CT scan is usually required to exclude space-occupying lesions and raised ICP before lumbar puncture.

CSF: Typical findings include:

CSF: Typical findings include:

– viral: increased lymphocytes, slightly raised protein and normal glucose.

Treatment is directed at the underlying organism. Recent UK guidelines suggest cefotaxime or ceftriaxone (both 2 g iv) as soon as possible (i.e. before definitive microbiological diagnosis). Ampicillin 2 g is added if > 55 years, to cover listeria or vancomycin ± rifampicin if penicillin-resistant pneumococcus is suspected. Dexamethasone (e.g. 0.15 mg/kg iv qds for 4 days) reduces mortality and neurological morbidity.

Important because of its innocuous early course, rapid progression and potentially disastrous outcome; the latter is thought to be related to the extremely toxic endotoxin present in the outer wall of the organism. An important cause of morbidity and mortality in children and young adults; epidemics (e.g. in schools/colleges) occur periodically. Asplenia and complement deficiency are specific risk factors. Shows seasonal variation (approximately 40% of cases occurring between January and March). The organism is present in the nasopharynx of about 5% of otherwise healthy subjects, increasing to about 30% during epidemics. Case mortality is 10–12% in the UK.

non-specific (especially initially), e.g. cough, sore throat, fever, vomiting, headache.

non-specific (especially initially), e.g. cough, sore throat, fever, vomiting, headache.

signs and symptoms of meningitis: may develop in about 85% of cases but bacteraemia and severe SIRS may occur without overt meningitis being present, and has a higher mortality.

signs and symptoms of meningitis: may develop in about 85% of cases but bacteraemia and severe SIRS may occur without overt meningitis being present, and has a higher mortality.

petechial rash: present in up to 80% of patients, although sometimes limited to the mucous membranes. May become maculopapular. DIC is common. Vasculitic lesions or extensive skin digit or limb necrosis (purpura fulminans) may also occur.

petechial rash: present in up to 80% of patients, although sometimes limited to the mucous membranes. May become maculopapular. DIC is common. Vasculitic lesions or extensive skin digit or limb necrosis (purpura fulminans) may also occur.

MODS and septic shock may occur.

MODS and septic shock may occur.

adrenocortical insufficiency due to sepsis or adrenal haemorrhage.

adrenocortical insufficiency due to sepsis or adrenal haemorrhage.

Diagnosis is often suggested by the history and clinical examination, although similar rashes can occur with staphylococcal, streptococcal or Haemophilus influenzae infections. Blood cultures reveal the meningococcus in up to 80% of untreated cases. The organism may also be isolated from the skin lesions or CSF. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is increasingly used to identify the organism.

iv antibiotic therapy as for meningitis.

iv antibiotic therapy as for meningitis.

limb fasciotomies or amputation may be necessary.

limb fasciotomies or amputation may be necessary.

others: specific anti-endotoxin antibodies and anti-cytokine therapies, corticosteroids and other treatments of severe sepsis have been studied but their place is uncertain.

others: specific anti-endotoxin antibodies and anti-cytokine therapies, corticosteroids and other treatments of severe sepsis have been studied but their place is uncertain.

If exposed before the patient has received appropriate antibiotics, close contacts (including ICU staff) should receive prophylaxis, e.g. with rifampicin or ciprofloxacin. At-risk subjects may be protected by immunisation with a polysaccharide vaccine against types A and C meningococci; the B serogroup has a number of subtypes and an effective vaccine against it has not yet been developed. Public health officials should be contacted (it is a notifiable disease) to organise contact tracing and prophylaxis.

Stephens DS, Greenwood B, Brandtzaeg P (2007). Lancet; 369: 2196–210

Mental Capacity Act 2005. Act providing a framework for decision making on behalf of adults without capacity; came into force in England and Wales in April 2007. Largely building on pre-existing common law, the Act confers formal statutory status on advance directives (termed advance decisions) and creates new ‘lasting powers of attorney’ and ‘court-appointed deputies’ with the ability to make medical decisions on behalf of adults > 16 years who lack capacity.

Mepivacaine hydrochloride. Amide local anaesthetic agent, first used in 1956. Similar to lidocaine, but more protein-bound. Does not cause vasodilatation. Not available in the UK. Used in 1–2% solutions for epidural anaesthesia and 4% solution for spinal anaesthesia, in the same doses as lidocaine. Maximal safe dose is 5 mg/kg; toxic plasma level is about 6 µg/ml. Rarely used in obstetrics because of greater fetal protein-binding and longer fetal half-life than alternative drugs.

Meptazinol hydrochloride. Synthetic opioid analgesic drug, first investigated in 1971. Has partial agonist properties, and therefore antagonises respiratory depression caused by morphine. Causes less respiratory depression or sedation than morphine. Analgesic effects are almost completely reversed by naloxone. 100 mg is equivalent to 10 mg morphine or 100 mg pethidine.

Meropenem. Broad-spectrum carbapenem and antibacterial drug, similar to imipenem but not broken down by renal enzymatic action. Less likely to cause convulsions than imipenem, thus more useful in CNS infections.

• Dosage: 500 mg–1 g iv over 5 min tds (2 g in meningitis or infection in cystic fibrosis).

Mesmerism. Treatment of various maladies (including postoperative pain relief) by ‘animal magnetism’, the transmission between individuals of healing force derived from the ubiquitous magnetic fluid that pervaded the universe. Named after Mesmer, who originally passed magnets over his patients’ bodies to treat them. He later used only his touch, and then speech, to achieve the same effects. Investigated in Paris by a French Royal Commission in 1784, which included Benjamin Franklin and Lavoisier; mesmerism was declared to have no scientific foundation, relying on suggestion alone. It continued to be popular until the 1840s, when the importance of psychological suggestion by the therapist was emphasised, leading to the concept of hypnotism.

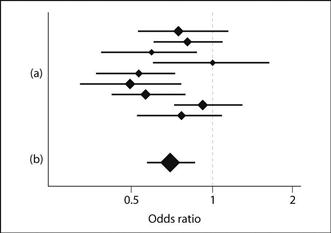

Meta-analysis (Systematic review). Technique for determining the efficacy of a treatment by combining trials that may individually have been too small to show a statistically significant difference. Requires careful inclusion of all randomised controlled trials (RCTs) of the particular treatment, some of which may not have been published. The RCTs are then scored according to their methodology, excluding any that are inadequately randomised or blinded. The results of the remaining RCTs are then pooled to increase the overall number of subjects and power; the outcome of each RCT is expressed in a standard format (e.g. odds ratio, number needed to treat, absolute or relative risk reduction) and the value for the combined data given. Typically, each separate RCT’s result is shown on a graph, with horizontal lines representing confidence intervals; the size of the central mark represents the sample size (forest plot; Fig. 105). The combined result therefore has smaller confidence intervals and larger central mark than the constituent RCTs, representing the greater certainty of the combined result and the larger number of subjects. Those trials whose confidence intervals cross the line of equivalence (for odds ratio, a value of one) are statistically ‘non-significant’ whilst those that do not are ‘significant’. In the example given, the overall conclusion is that there is a statistically significant difference, as demonstrated by the combined confidence intervals not crossing the line.

differing definitions of selection criteria for RCTs.

differing definitions of selection criteria for RCTs.

use of different outcomes in the component studies.

use of different outcomes in the component studies.

the ability for single RCTs to influence unduly the overall result in certain circumstances.

the ability for single RCTs to influence unduly the overall result in certain circumstances.

Thus there have been some famous examples of treatment effects apparently demonstrated by meta-analysis that have not been supported by subsequent huge RCTs, e.g. the ‘beneficial’ effect of magnesium sulphate following MI. However, meta-analysis has had notable successes too, e.g. by demonstrating clearly the reduction in mortality when β-adrenergic receptor antagonists are given following MI despite conflicting results of the many small RCTs that previously existed.

Metabolism. Physical and chemical reactions occurring in an organism in order to sustain life. Involves anabolism (building up; i.e. incorporation of substrate into living cells) and catabolism (breaking down; usually concerned with energy liberation). Metabolic pathways are mediated by enzymes, subject to various control mechanisms (e.g. hormonal). Basic pathways may be discussed in terms of dietary substrate:

carbohydrates: digested to monosaccharides, absorbed and passed to liver and muscle. Glucose is converted to glycogen for storage or broken down via glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid cycle and cytochrome oxidase system to CO2 and water with liberation of energy that is stored in ATP and other compounds.

carbohydrates: digested to monosaccharides, absorbed and passed to liver and muscle. Glucose is converted to glycogen for storage or broken down via glycolysis, tricarboxylic acid cycle and cytochrome oxidase system to CO2 and water with liberation of energy that is stored in ATP and other compounds.

fats: digested to fatty acids and glycerol, which pass to the liver. Stored as adipose tissue or oxidised to CO2, water and energy.

fats: digested to fatty acids and glycerol, which pass to the liver. Stored as adipose tissue or oxidised to CO2, water and energy.

proteins: digested to amino acids; form new proteins, e.g. enzymes, secretions, cellular components such as muscle. Subsequently broken down to urea.

proteins: digested to amino acids; form new proteins, e.g. enzymes, secretions, cellular components such as muscle. Subsequently broken down to urea.

Metaraminol tartrate/bitartrate. Vasopressor drug, acting directly via α-adrenergic receptors, and indirectly via adrenaline and noradrenaline release. Increases cardiac output and SVR, and thus arterial BP. Used to raise BP following epidural/spinal anaesthesia and cardiogenic shock. May cause excessive hypertension in hyperthyroidism and monoamine oxidase inhibitor therapy, and myocardial ischaemia in ischaemic heart disease.

• Dosage:

2–10 mg sc or im; acts within 10 min and lasts 1–1.5 h.

2–10 mg sc or im; acts within 10 min and lasts 1–1.5 h.

in severe hypotension or shock: 0.5–5 mg iv, titrated to effect; acts within 1–2 min, lasting for 20–30 min.

in severe hypotension or shock: 0.5–5 mg iv, titrated to effect; acts within 1–2 min, lasting for 20–30 min.

Methadone hydrochloride. Synthetic opioid analgesic drug, formulated in 1947. Due to its long duration of action (up to 24 h), used for chronic pain management, maintenance in opioid addicts and cough suppression in palliative care. Has similar actions and side effects to morphine, but is generally milder with less sedation. Elimination half-life exceeds 18 h. Accumulation may be problematic.

Methaemoglobinaemia. Increased circulating haemoglobin in which the iron atom of haem is in the ferric (Fe3+) state (normally < 1%). Levels determined by co-oximetry.

• May be:

– deficiency of reducing enzymes (especially cytochrome b5 oxidase), that normally convert endogenously formed methaemoglobin to haemoglobin. Usually autosomal recessive inheritance; heterozygotes may be at risk of acute acquired methaemoglobinaemia.

– abnormal haemoglobin chains, with fixation of iron in Fe3+ state; autosomal dominant inheritance.

– glucose 6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency.

acquired: drugs and chemicals, e.g. prilocaine, chlorate, quinones, nitrites, phenacetin, sulphonamides, aniline dyes.

acquired: drugs and chemicals, e.g. prilocaine, chlorate, quinones, nitrites, phenacetin, sulphonamides, aniline dyes.

• Effects:

because methaemoglobin is dark (brownish), patients appear to have cyanosis when levels exceed 10–12% (at normal haemoglobin concentrations). Inaccurate readings of haemoglobin saturation may occur with pulse oximetry (as the level of methaemoglobin increases, measured arterial O2 saturation tends towards 85% since both oxygenated and deoxygenated forms absorb light equally at 660 nm and 940 nm).

because methaemoglobin is dark (brownish), patients appear to have cyanosis when levels exceed 10–12% (at normal haemoglobin concentrations). Inaccurate readings of haemoglobin saturation may occur with pulse oximetry (as the level of methaemoglobin increases, measured arterial O2 saturation tends towards 85% since both oxygenated and deoxygenated forms absorb light equally at 660 nm and 940 nm).

the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve of the unaffected haem is shifted to the left, reducing O2 delivery to tissues. Patients already anaemic are more at risk. Dyspnoea and headache are common at > 20% methaemoglobin, although rate of formation is also important.

the oxyhaemoglobin dissociation curve of the unaffected haem is shifted to the left, reducing O2 delivery to tissues. Patients already anaemic are more at risk. Dyspnoea and headache are common at > 20% methaemoglobin, although rate of formation is also important.

Methanol poisoning, see Alcohol poisoning

Methionine and methionine synthase. Methionine (an amino acid) is the main source of methyl groups in the body, and is involved in many biochemical reactions, including myelination. It is also the precursor of glutathione, depleted in the liver by toxins, e.g. paracetamol poisoning, hence its use in the latter. Formation from homocysteine by methionine synthase is involved in folate metabolism, and thymidine and DNA synthesis.

Methionine synthase containing vitamin B12 as a cofactor is inhibited by N2O, which interacts directly with the vitamin. Prolonged exposure to N2O may result in features of folate/vitamin B12 deficiency, e.g. subacute combined degeneration of the cord and megaloblastic anaemia. Myelination may also be affected. Significant effects are thought to be minimal up to 8 h normal anaesthetic use, but biochemical changes have been found after a few hours. Megaloblastic changes have been found in dentists who use N2O. Effects on DNA synthesis may mediate teratogenesis after prolonged exposure in animal models, but teratogenicity in humans during routine anaesthesia is considered negligible.

Methohexital sodium (Methohexitone). IV anaesthetic drug, first used in 1957 and discontinued in the UK in 2000. A methyl barbiturate, presented as a white powder with 6% anhydrous sodium carbonate. pH of 1% solution: 10–11. pKa is 7.9; thus a greater proportion remains unionised in plasma than with thiopental. Used mainly for day-case surgery and short procedures, including electroconvulsive therapy (because of its pro-convulsant properties).

Properties are similar to those of thiopental but pain on injection, involuntary movement, hiccup and laryngospasm are more likely. Adverse effects of intra-arterial injection are less than with thiopental, due to the more dilute solution. Recovery is within 3–4 min of a single dose of 1.0–1.5 mg/kg, with half-life 2–4 h.

Methotrexate. Antimetabolite cytotoxic drug; inhibits dihydrofolate reductase, thus blocking purine and pyrimidine synthesis and preventing cell division. Used in the treatment of various malignancies, including acute lymphoblastic leukaemia; also used in severe psoriasis and rheumatoid arthritis. May accumulate in pleural or ascitic fluid, producing systemic toxicity subsequently. Excreted renally; thus NSAIDs are contraindicated since reduced renal function may increase toxicity.

Methoxamine hydrochloride. Vasopressor drug, acting via selective α1–adrenergic receptor stimulation. Used (1–2 mg iv) to raise BP (e.g. during epidural or spinal anaesthesia) and to treat SVT. Causes a reflex bradycardia via the baroreceptor reflex. Discontinued in 2001 because of falling global demand.

Methoxyflurane. CHCl3CF2OCH3. Inhalational anaesthetic drug, first used in 1960. Cheap and non-explosive, but withdrawn from practice because of high-output renal failure caused by fluoride ion production. Has high boiling point (105°C) and therefore difficult to vaporise. Very soluble in blood (blood/gas partition coefficient of 13); induction and recovery are therefore slow. Extremely potent (MAC 0.2) and a powerful analgesic. Formerly used for general anaesthesia and draw-over analgesia, e.g. during labour, using the Cardiff fixed output (0.35%) inhaler. Still available for use in Australia and New Zealand for pre-hospital analgesia.

N-Methyl-D-aspartate receptors (NMDA receptors). Receptors in the CNS activated by glutamate (but requiring glycine as a co-agonist) and to a lesser extent aspartate; involved in the plasticity of the CNS to afferent impulses, especially pain. Activation by sustained or repeated C-fibre stimulation leads to intracellular phosphorylation of proteins and causes opening of specific membrane ion channels (opposed by magnesium). This leads to an increase in intracellular calcium concentration and increased response to glutamate by a positive feedback mechanism. Thus input via NMDA receptors is thought to lead to a hyperexcitable state (‘wind-up’) whereby repeated stimuli cause increasing degrees of pain sensation and expansion of the receptive field of individual sensory neurones involved in pain pathways. NMDA receptor antagonists are thought to prevent these phenomena and may thus have a role in pre-emptive analgesia. Also has a major role in long-term neuronal potentiation and depression involved in memory and learning. The only NMDA antagonist available for use in the UK is ketamine, which is used in low doses (e.g. 0.1–0.2 mg/kg) before skin incision to reduce postoperative pain.

NMDA receptor-mediated calcium influx is also thought to contribute to neuronal cell death following cerebral ischaemia and in neurodegenerative disorders. An autoimmune encephalitis due to antibodies directed at NMDA receptors has been described.

Petrenko AB, Yamakura T, Baba H, Shimoji K (2003). Anesth Analg; 97: 1108–16

α-Methyldopa. Antihypertensive drug, originally thought to act via uptake into catecholamine synthetic pathways and formation of a ‘false transmitter’, α-methylnoradrenaline. The latter is now thought to have a direct antihypertensive action of its own, possibly via stimulation of central inhibitory α-adrenergic receptors, or reduction of plasma renin activity. Superseded by newer drugs, but it is still occasionally used, e.g. in pre-eclampsia (shown to be non-teratogenic).

• Dosage:

250 mg orally bd/tds, titrated to response (maximum 3 g/day).

250 mg orally bd/tds, titrated to response (maximum 3 g/day).

leucopenia, hepatitis, haemolytic anaemia. 10–20% of patients have a positive direct Coombs’ test that may interfere with blood compatibility testing (see Haemolysis). A SLE-like syndrome has been reported.

leucopenia, hepatitis, haemolytic anaemia. 10–20% of patients have a positive direct Coombs’ test that may interfere with blood compatibility testing (see Haemolysis). A SLE-like syndrome has been reported.

Methylenedioxyethylamfetamine, see Methylenedioxymethylamfetamine

Methylenedioxymethylamfetamine (MDMA; ‘Ecstasy’). Synthetic amfetamine-like stimulant drug, abused recreationally, especially in association with prolonged dancing. Psychological effects include feelings of euphoria and increased intimacy with others. Toxicity has been associated with collapse and sudden death, particularly when combined with extreme physical exertion and dehydration. Has been associated with hyperthermia (thought to involve central 5-HT pathways and not peripheral mechanisms as in MH), arrhythmias and hepatic failure. With increasing awareness that concurrent dehydration may be harmful, cases of hyponatraemia caused by excessive water intake have been reported. Degeneration of central neurones has also been reported after prolonged exposure. Most cases of acute critical illness involve hyperthermia that may be associated with severe acidosis, DIC and rhabdomyolysis.

Management of acute toxicity is mainly supportive. Hyperthermia is treated with active cooling; dantrolene has been used.

Methylmethacrylate. Acrylic cement used in orthopaedic surgery for fixation of prostheses. Thought to be the cause of hypotension, hypoxaemia or cardiovascular collapse upon prosthesis insertion, although the mechanism is unclear.

direct cardiotoxicity of the monomer.

direct cardiotoxicity of the monomer.

activation of the coagulation cascade within the pulmonary vasculature.

activation of the coagulation cascade within the pulmonary vasculature.

fat or air embolism resulting from insertion of lipid-soluble cement into the bone cavity under pressure.

fat or air embolism resulting from insertion of lipid-soluble cement into the bone cavity under pressure.

Donaldson AJ, Thomson HE, Harper NJ, Kenny NW (2009). Br J Anaesth; 102: 12–22

Methylnaltrexone bromide. Peripherally acting mu opioid receptor antagonist licensed as a treatment for opioid-induced constipation in patients receiving palliative care. Does not cross the blood–brain barrier, thus devoid of central effects.

Methylprednisolone, see Corticosteroids

α-Methyl-p-tyrosine (Metirosine). Antihypertensive drug; inhibits conversion of tyrosine to dopa, thus blocking catecholamine synthesis. Available on a named patient basis in the UK. Has been used to reduce the incidence and severity of hypertensive episodes in phaeochromocytoma, e.g. before or instead of surgery. Should not be used in essential hypertension.

Meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, see Infection control; Staphylococcal infections

Metoclopramide hydrochloride. Antiemetic drug, acting via dopamine receptor antagonism at the chemoreceptor trigger zone. Also a prokinetic drug, increasing gastric emptying and lower oesophageal sphincter pressure via a peripheral cholinergic action, but will not reverse the effects of opioid analgesic drugs in this respect unless given iv. It also decreases the sensitivity of visceral afferent nerves to local emetics and irritants. Has little effect on PONV if 10 mg is given iv on induction of anaesthesia, but significantly reduces PONV if 20 mg is given towards the end of surgery. Half-life is about 4–6 h.

• Dosage:

10 mg iv, im or orally tds as required. Total daily dose: 0.5 mg/kg.

10 mg iv, im or orally tds as required. Total daily dose: 0.5 mg/kg.

has been used in very high doses (up to 5 mg/kg iv) to treat vomiting caused by cytotoxic therapy; thought to antagonise central 5-HT3 receptors.

has been used in very high doses (up to 5 mg/kg iv) to treat vomiting caused by cytotoxic therapy; thought to antagonise central 5-HT3 receptors.

• Side effects: extrapyramidal effects and dystonic reactions (particularly affecting the face), especially following iv administration in children or young adults. Hypotension and tachy- or bradycardia may occur after rapid injection. Has been associated with methaemoglobinaemia and sulphaemoglobinaemia if taken chronically or in high dosage.

Metocurine, see Dimethyl tubocurarine chloride/bromide

Metoprolol tartrate. β-Adrenergic receptor antagonist, available for oral and iv administration. Relatively selective for β1-receptors. Uses and side effects are as for β-adrenergic receptor antagonists in general.

• Dosage:

acute administration: 2–4 mg slowly iv, repeated up to 10 mg.

acute administration: 2–4 mg slowly iv, repeated up to 10 mg.

acute coronary syndromes: 5 mg iv every 2 min up to 15 mg if haemodynamically tolerated; then 15 min later 50 mg orally qds for 48 h.

acute coronary syndromes: 5 mg iv every 2 min up to 15 mg if haemodynamically tolerated; then 15 min later 50 mg orally qds for 48 h.

Metre. SI unit of length. Originally defined according to the length of a platinum–iridium bar kept at Sèvres, France, but redefined in 1960 according to the speed of light in a vacuum, following doubts as to the bar’s constant length over time: 1 metre = the distance occupied by 1 650 763.73 wavelengths of a specified orange-red light from gaseous krypton-86.

Metronidazole. Antibacterial drug, active against a wide range of anaerobic bacteria and protozoa. Used in many infections, especially gastrointestinal and gynaecological. Undergoes hepatic metabolism and renal excretion, with a half-life of 8.5 h. Tinidazole has similar actions but a longer duration of action and is given once daily.

• Dosage:

1 g pr tds for 3 days, then bd.

1 g pr tds for 3 days, then bd.

• Side effects: disulfiram-like reaction, nausea, vomiting, urticaria; rarely drowsiness, ataxia; on prolonged dosage peripheral neuropathy, convulsions, leucopenia, urine discoloration.

Mexiletine hydrochloride. Class Ib antiarrhythmic drug; reduces fast sodium entry and shortens the refractory period. Chemically related to lidocaine, but active orally. Half-life is 10 h. Used to treat ventricular arrhythmias.

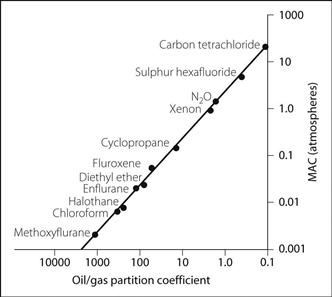

Meyer–Overton rule. Describes the positive correlation between anaesthetic potency of inhalational anaesthetic agents and lipid solubility. Can be seen if MAC is plotted against oil/gas partition coefficients at 37°C for various agents, using logarithmic scales (Fig. 106).

See also, Anaesthesia, mechanism of

Fig. 106 Meyer–Overton rule

digits, extending to their dorsal surface at their tips.

digits, extending to their dorsal surface at their tips.