Lymphocytes

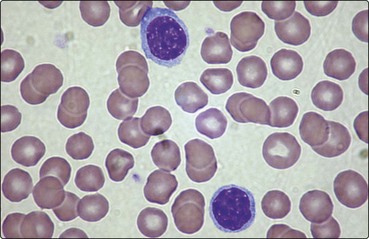

Most mature lymphocytes appear under the light microscope as cells with round nuclei and a thin rim of agranular cytoplasm (Fig 4.1). Although B- and T-cells are not distinguishable by their morphology, there are major differences in their mode of maturation and function.

T-lymphocytes

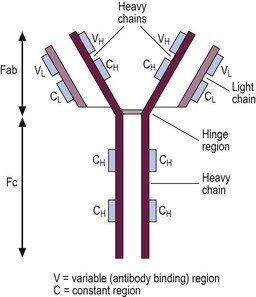

T-cells make up 75% of the lymphocytes of the blood and form the basis of cell-mediated immunity. They are less autonomous than their B-cell companions, needing the cooperation of antigen-presenting cells expressing self-histocompatibility molecules (human leucocyte antigens (HLA)) for the recognition of the antigen by the T-cell receptor (TCR) (Fig 4.2).

Fig 4.2 Interaction of T-lymphocyte and antigen-presenting cells.

The T-cell receptor complex (TCR) recognises the combination of processed antigen and major histocompatibility complex (MHC) molecule and the immune response is initiated.

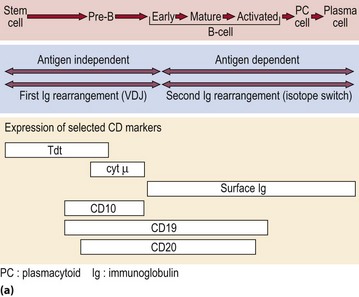

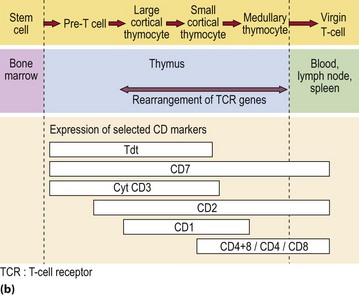

T-cells originate in the marrow but many are destroyed in subsequent processing by the thymus, the objective being to select the minority of cells which will recognise self-HLA but not react with self-tissue antigens. The maturation sequence is characterised by changing patterns of cell surface molecules (Fig 4.3). Mature T-cells are divisible into two basic types. About two-thirds of blood T-cells are ‘helper’ cells expressing the surface marker CD4, while the remainder express CD8 and are mostly of ‘cytotoxic’ type.

Fig 4.3 Maturation of B- and T-lymphocytes.

(a) B-lymphocyte maturation in the bone marrow. (b) T-lymphocyte development in the bone marrow and thymus.

It appears that helper cells recognise the combination of antigen and self-HLA class II molecules on the antigen-presenting cell, and cytotoxic cells bind with antigen in conjunction with HLA class I molecules on the target cell (Fig 4.2). TCR genes, like Ig genes, are subject to rearrangement of germ-line DNA. Following triggering of T-cells by specific antigen reacting with the TCR, the clonal proliferation of activated T-cells is sustained by the secretion of cytokines. Interleukin-2 is the main T-cell growth factor.

B-lymphocytes

B-cells are derived from the stem cells of the bone marrow. Unlike T-cells it is not clear whether they are subject to further processing at a site outside the marrow in humans. The various stages of B-cell maturation are illustrated in Figure 4.3. Each cell can be defined by its expression of membrane and cytoplasmic antigens in addition to the stage of immunoglobulin gene rearrangement. Within the lymphoid tissues, such as the lymph nodes and spleen, mature unactivated or virgin B-cells can be stimulated by antigen to undergo a morphological transformation into immunoblasts and, ultimately, plasma cells.

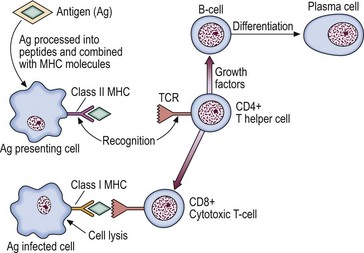

Stimulation of a single B-cell by antigen combining with its cell surface immunoglobulin variable region leads to a sequence of proliferation and differentiation resulting in a clone of immunoglobulin-secreting plasma cells. This adaptive immune response is antigen-specific and is facilitated by helper T-cells and cytokine-secreting macrophages. Memories of particular antigens are immortalised by ‘memory’ B-cells, allowing a prompt response to reinfection. The immunoglobulins secreted by lymphocytes and plasma cells are heterogeneous proteins, each designed to interact with a specific antigen in the defence of the body against infection (Fig 4.4). There are five subclasses of immunoglobulin (Ig), dependent on the type of heavy chain (IgG, IgA, IgM, IgD and IgE), with some further division of subclasses (e.g. IgG1–4). IgM is generally produced as the initial response to infection, followed by a more prolonged production of IgG. IgA is found in secretions, while IgE plays a role in delayed hypersensitivity reactions.

Changes in disease

A number of lymphoid malignancies are associated with lymphocytosis (Table 4.1). In acute lymphoblastic leukaemia and ‘spill-over’ of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma cells into the blood, the malignant lymphocytes are usually morphologically distinctive and confusion with a reactive lymphocytosis rarely occurs. In chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL), the lymphocytes often appear unremarkable although the presence of disrupted forms, termed ‘smear cells’, is characteristic.

Table 4.1

Common causes of a lymphocytosis

| Infections | Acute viral infections (e.g. pertussis, infectious mononucleosis, rubella) |

| Chronic infections (e.g. tuberculosis, toxoplasmosis) | |

| Malignancy | Chronic lymphocytic leukaemia and variants |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (minority) | |

| Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia |