69 Lung Transplantation

Historical Perspective

Historical Perspective

Lung transplantation evolved from heart-lung transplantation as a method by which donor organs could be used more efficiently. Heart-lung transplantation was first performed in 19811 and was initially the procedure of choice for diseases that are now more commonly treated by transplant using either bilateral sequential lung transplantation or single-lung transplantation. The appeal of developing the isolated lung transplant technique was improvement in donor organ utilization. Specifically, by using each of the three thoracic organs available from a single donor (i.e., two lungs and a heart), donor organ utilization can be maximized while achieving acceptable outcomes.

Single-lung transplantation was first described in 1986.2 The advantage of the procedure is that it has allowed maximal donor utilization while being associated with good patient outcomes. The single-lung procedure has historically been accepted as the procedure of choice for common transplant indications such as emphysema and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and is currently performed as commonly as the bilateral procedure.3

Survival and Demographics

Survival and Demographics

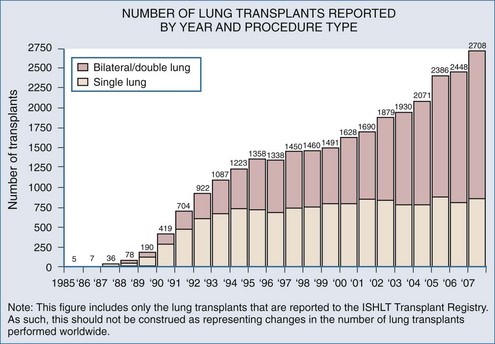

Worldwide, 1200 to 1400 patients receive a lung transplant each year. Despite the yearly increase in patients on the transplant waiting list (recently nearly 4000 patients), the number of transplant procedures performed each year has been relatively stable over the past several years (Figure 69-1).3 Significant discussion and research regarding methods to expand the donor pool are ongoing,4 but until strategies to increase lung donor procurement are actually employed, the number of transplants performed each year will likely remain stable.

Indications and Procedure Choice

Indications and Procedure Choice

Indications for lung transplant are listed in Table 69-1 according to the generally accepted procedure choice. Although there are many end-stage lung diseases that can potentially be amenable to lung transplantation, four diseases account for the vast majority of lung transplant recipients: emphysema (both cigarette-induced and due to alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency), cystic fibrosis, primary pulmonary hypertension, and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.3 Contraindications to transplant include evidence of extrapulmonary disease such as significant kidney, liver, or cardiac disease; poor nutritional or rehabilitation status; recent or current malignancy; and a poor psychosocial profile.

TABLE 69-1 Lung Transplant by Procedure Type (in Order of Frequency)

| Single-Lung Transplant | Double-Lung Transplant |

|---|---|

| Emphysema/chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) | Cystic fibrosis |

| Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis | Emphysema/COPD |

| Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency | Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency |

| Re-transplant | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis |

| Primary pulmonary hypertension | |

| Bronchiectasis |

Generally the procedure of choice is the one that can be performed safely while utilizing the available donor organs most efficiently. Emphysema is the most common lung transplant indication and has consistently been associated with the best survival post transplant.3 While some controversy exists regarding the optimal procedure choice (single versus double) in this group of patients,5 most patients with emphysema who have undergone a lung transplant have received a single-lung transplant. Bilateral lung transplant has traditionally been reserved for suppurative lung diseases, such as cystic fibrosis, and other bronchiectatic disease where replacing as much infected lung tissue as possible is the primary goal. Patients with primary pulmonary hypertension generally receive a bilateral lung transplant because this prevents the potentially life-threatening situation that occurs when, in performing a unilateral transplant, nearly all cardiac output flows to the allograft, given its relatively lower vascular resistance compared to the native primary pulmonary hypertension lung. In the early transplant period when single lungs were transplanted for this indication, the result in most centers was profound unilateral pulmonary edema in the allograft.

Donor Criteria

Donor Criteria

The expansion of lung transplantation as a therapy for end-stage lung disease is not limited by the number of potential recipients but rather by the availability of suitable donor organs. The standard, or “classic,” lung donor criteria are well known, if not closely followed, among lung transplant practitioners. Although some of these criteria certainly make good sense (i.e., a clear chest radiograph, no bronchoscopic evidence of aspiration), nearly all the others are controversial, often ignored, and not based on convincing research data.4 The standard or classic lung donor criteria are listed in Table 69-2. Whereas certain geographic regions in the United States, some countries in Europe, and Australia have adopted more aggressive donor management strategies that have resulted in more donor lungs, many areas with lung transplant programs have fewer than expected lung donors.

Postoperative Care

Postoperative Care

Ventilator and Respiratory Management

Single-Lung Versus Double-Lung Issues

Management of the mechanical ventilator after lung transplant surgery is heavily influenced by the type of lung transplant procedure performed (i.e., a single- or double-lung transplant). In recipients who receive a bilateral transplant, ventilator management is very similar to that for nontransplant patients. However, in single-lung recipients, the compliance differences between the native lung and the allograft mandate different ventilator strategies. Different strategies are particularly important in single-lung recipients with emphysema, rather than in single-lung recipients with fibrotic lung, owing to the tendency of the native emphysematous lung to hyperinflate under the influence of positive pressure. This tendency is the reason some programs have advocated double-lung transplants routinely for patients with emphysema because of their potential for increased mortality with single-lung transplant.6 Fortunately, proper ventilator management in single-lung recipients can prevent most of the problems with native lung hyperinflation, and concerns about this phenomenon should not influence procedure choice.7

Native lung hyperinflation is more common when acute lung injury is present in the allograft, because the compliance discrepancy between the native lung and the allograft is even more pronounced. In this rare circumstance, independent lung ventilation using a double-lumen endotracheal tube can be initiated and can provide a means to ventilate the native lung and allograft according to the compliance characteristics of each.8 Independent lung ventilation outside of the operating room setting is associated with difficulties, particularly relating to endotracheal tube malpositioning and subsequent acute lobar or total lung collapse. Prevention and recognition of tube dislodgment requires constant surveillance, generally endoscopically, and is difficult unless personnel skilled with endoscopic endotracheal tube management skills are available on a continuous basis. Under these circumstances, diligent nursing care is required, including the administration of appropriate sedation and/or paralytic agents as well as the avoidance of routine repositioning of the patient.

Extubation

The extubation criteria in a lung transplant recipient are similar to those for other types of ventilated patients, particularly postsurgical patients. The patient should certainly be free of any lingering effects of the anesthetic and able to meet standard extubation criteria.9 As more experience with lung transplant management has developed, the decision to extubate is being made sooner, and some centers are even trying to extubate patients in the operating suite soon after surgery.10 Other programs, however, are reluctant to extubate this quickly because of concerns about delayed ischemia-reperfusion injury that would compromise allograft function or uncertainty about whether anesthetic medications have been completely cleared. Regardless, the dogma about leaving patients ventilated for a predetermined amount of time is now being challenged.

Immunosuppressive Regimens

Commonly Used Agents

Different transplant centers use different immunosuppressive regimens. However, general comments can be made about the more commonly used medications. Some programs use an induction strategy that involves the early administration of antibody, either directed directly at the lymphocyte (“lymphocyte-depleting”) or against interleukin receptor sites.11 Most antibodies delivered are monoclonal and are better tolerated than the polyclonal antibodies used in the earlier transplant era. Regardless of which induction agent is preferred, a primary advantage of this strategy involves the early avoidance of nephrotoxic immunosuppressive agents (such as calcineurin inhibitors like cyclosporine or tacrolimus), while still providing adequate immunosuppression. This benefit is particularly important during the immediate postoperative period when renal insufficiency is common owing to purposeful intravascular volume depletion, use of nephrotoxic antibiotics and antiviral agents, and the effects of cardiopulmonary bypass (if used).

The third part of the immunosuppressive regimen involves the use of either azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil. Azathioprine is generally well tolerated and is usually associated with mild, reversible side effects such as leukopenia, anemia, thrombocytopenia, and liver function test abnormalities. Mycophenolate mofetil, a newer agent, can also cause leukopenia and anemia. In some circumstances, the drug can lead to nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain, all of which can be ameliorated by reducing the dose or temporarily stopping the drug. Monitoring of mycophenolic acid blood levels is being performed in some solid organ recipients,12,13 but the precise target levels in lung transplantation are unknown.

Infectious Disease Prophylaxis

Infection with CMV after transplant can lead to deleterious acute and chronic effects. Acutely, patients are at risk to develop CMV pneumonia which, in many instances, leads to severe morbidity and mortality. CMV syndrome, caused by CMV replication in the bloodstream, is heralded by the onset of malaise, fever, nausea, and vomiting. Furthermore, many believe that CMV infection (even asymptomatic) can lead to more long-term sequelae such as chronic allograft dysfunction (BOS).14

To prevent both the acute and chronic consequences of CMV infection, many programs have adopted an aggressive CMV prophylactic protocol. The more aggressive protocols include combination therapy using both ganciclovir and CMV hyperimmune globulin.15 The duration of therapy is dependent on CMV serology status of the donor and the recipient and is outlined in Table 69-3. Other less aggressive strategies are also used and, although less expensive and associated with less treatment-associated toxicity, likely lead to an increased incidence of CMV-related diseases.

| Recipient Positive | Recipient Negative | |

|---|---|---|

| Donor Positive | 6 wk GCV* (2 wk IV and 4 wk PO) | 12 wk GCV* (6 wk IV, PO) |

| CMV-IG 3 doses (1 dose every 2 wk) | CMV-IG† 7 doses in 6 wk | |

| Donor Negative | No prophylaxis used |

CMV IG, cytomegalovirus hyperimmune globulin; GCV, ganciclovir; IV, intravenous; PO, per os (oral).

* Intravenous dose 5 mg/kg q 12 h adjusted for creatinine clearance.

† 150 mg/kg within 72 h post transplant, then every 2 weeks for 4 doses, then 100 mg/kg every 4 weeks for 2 additional doses

Prophylactic use of antifungal agents is controversial and varies among centers.16 There are single-center studies that have demonstrated a reduction in invasive fungal disease after instituting a fungal prophylactic regimen.17 Programs that do use antifungal prophylaxis generally use medications in the azole class or aerosolized amphotericin.18,19 While there have been no conclusive studies in lung transplant to support an antifungal prophylactic strategy, some lung transplant physicians use these agents primarily for their ability to raise blood levels of the calcineurin inhibitors, which ultimately results in significant cost savings because the calcineurin inhibitor dose can be reduced.20 One concern with this strategy, however, is the potential to select for resistant fungal infections, particularly candidal species.

Intensive Care Unit Issues

Intensive Care Unit Issues

In the early postoperative period while the patient is mechanically ventilated, the use of sedative medications and paralytics is common. However, in most cases, when early allograft function is adequate, the routine use of paralytic medications can be avoided. Avoidance of these drugs is desirable given that paralyzing agents have been associated with prolonged paralysis, which in lung transplant recipients can impair ability to wean from mechanical ventilation and to participate fully in the postoperative physical therapy regimen. The deleterious effects of paralytic agents can be exacerbated by concomitant use of high-dose corticosteroids and aminoglycoside antibiotics,21 both of which are commonly used in the early postoperative period in lung transplant recipients.

Early Postoperative Complications

Ventilatory Instability

Problems with early allograft function lead to inadequate ventilation and oxygenation. These problems are usually temporary and are best managed through supportive measures. However, in the case of primary graft failure, oxygenation and ventilatory problems are more profound and require more complex management strategies. In the setting of a double-lung transplant, management should include the application of increased levels of PEEP and, if necessary, alterations of inspiratory-to-expiratory ratios. In single-lung recipients, one can selectively ventilate the native lung while other measures are taken to improve allograft performance. This strategy can be accomplished through the use of double-lumen endotracheal tubes, which allow independent lung ventilation.22 In cases of significant allograft dysfunction, positioning the patient on the side with the native lung “down” can lead to increased perfusion to that side (i.e., the side with less pulmonary edema) and can lead to improvements in oxygenation.

Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation

In instances in which none of the measures described results in hemodynamic and ventilatory stability, ECMO is an alternative treatment strategy.23–25 Although associated with significant morbidity, ECMO can rapidly restore hemodynamic and ventilatory stability. Important morbidity as a result of this therapy includes bleeding complications secondary to the anticoagulation necessary to maintain the ECMO circuit. Bleeding can occur anywhere and is particularly evident at the cannula insertion site. However, intracranial hemorrhage is the most catastrophic complication and the most common cause of death associated with ECMO.26 The preferred ECMO method in lung transplant recipients is generally the venoarterial route, although the venovenous route has been used as well.27 Insertion of the ECMO cannulas is best performed at the femoral site, because local control of bleeding can be achieved. Although associated with good hemodynamic stability, central cannulization often results in poorly controlled bleeding.

Operative Complications

Postoperative bleeding issues are similar to those present in other thoracic surgical patients and are best handled by correction of coagulopathies and replacement of red blood cells. As in other thoracic patients, careful chest tube output monitoring is essential in detecting and ultimately treating excessive bleeding. Return to the operating room for exploration in the presence of excessive bleeding is not uncommon after lung transplantation. Bleeding complications are generally more common in patients in whom dissection to free the native lung is difficult, such as in cystic fibrosis patients or in patients with fibrotic lung diseases. There is also a tendency toward more bleeding in patients who have required cardiopulmonary bypass.28

As improvements in surgical technique have developed, a decrease in airway, venous, and pulmonary artery anastomotic complications has occurred.29 Although uncommon, anastomotic complications in the immediate postoperative period generally involve the vascular connections rather than the bronchial anastomosis. Complications with the bronchial anastomosis, such as dehiscence or stricture, usually occur later in the postoperative period. Conversely, problems with venous30,31 or pulmonary artery anastomoses32 manifest immediately postoperatively and are life threatening, particularly if not detected promptly.

Pulmonary artery stricture, or narrowing, is fortunately very uncommon. When it does occur, problems with oxygenation are seen and usually occur in the absence of radiographic abnormalities. The diagnosis is initially one of exclusion, where more common causes of poor oxygenation are investigated first. Once no evidence of other causes of poor allograft function can be found, evaluation of the pulmonary artery anastomosis should occur and usually is best accomplished via pulmonary angiography. Pulmonary perfusion scanning can, in some instances, be helpful and is noninvasive. However, nonspecific alterations in allograft blood flow do not distinguish among the usual causes of postoperative allograft dysfunction. Pulmonary angiography, on the other hand, can anatomically demonstrate pulmonary artery narrowing and provides the means to measure pressure gradients across the pulmonary artery anastomosis.33 If a significant gradient across the pulmonary artery anastomosis were to exist, the suspicion of a pulmonary artery stricture would be high enough to warrant surgical re-exploration.

Of the complications associated with vascular anastomoses, problems with the venous anastomosis are most common. Because of the technical challenges associated with establishing the venous anastomosis and the low-flow state of the venous system, the venous anastomosis is susceptible to kinking or clot formation. Both of these complications cause impedance of venous return and backflow of blood into the pulmonary vasculature. This results in immediate and profound pulmonary edema that is refractory to all supportive measures. A clinical scenario of this kind should prompt immediate investigation, ideally via visualization and Doppler measurement of the venous anastomosis using transesophageal echocardiography.34,35

Key Points

Garrity ERJr, Villanueva J, Bhorade SM, Husain AN, Vigneswaran WT. Low rate of acute lung allograft rejection after the use of daclizumab, an interleukin 2 receptor antibody. Transplantation. 2001;71(6):773-777.

Liu V, Zamora MR, Dhillon GS, Weill D. Increasing lung allocation scores predict worsened survival among lung transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2010;10(4):915-920.

Meyers BF, Sundt TM3rd, Henry S, et al. Selective use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation is warranted after lung transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;120(1):20-26.

Weill D, Lock BJ, Wewers DL, et al. Combination prophylaxis with ganciclovir and cytomegalovirus (CMV) immune globulin after lung transplantation: effective CMV prevention following daclizumab induction. Am J Transplant. 2003;3(4):492-496.

Weill D, Torres F, Hodges TN, Olmos JJ, Zamora MR. Acute native lung hyperinflation is not associated with poor outcomes after single lung transplant for emphysema. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999;18(11):1080-1087.

Yonan NA, el-Gamel A, Egan J, Kakadellis J, Rahman A, Deiraniya AK. Single lung transplantation for emphysema: predictors for native lung hyperinflation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1998;17(2):192-201.

1 Reitz BA, Wallwork JL, Hunt SA, et al. Heart-lung transplantation: successful therapy for patients with pulmonary vascular disease. N Engl J Med. 1982;306(10):557-564.

2 Toronto Lung Transplant Group. Unilateral lung transplantation for pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med. 1986;314:1140-1145.

3 Trulock EP, Edwards LB, Taylor DO, et al. The Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Twentieth Official Adult Lung and Heart-Lung Transplant Report—2003. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2003;22:625-635.

4 Weill D. Donor criteria in lung transplantation: An issue revisited. Chest. 2002;121:2029-2031.

5 Weill D, Keshavjee S. Lung transplantation for emphysema: Two lungs or one. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20:739-742.

6 Yonan NA, el-Gamel A, Egan J, et al. Single lung transplantation for emphysema: Predictors for native lung hyperinflation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1998;17:192-201.

7 Weill D, Torres F, Hodges TN, et al. Acute native lung hyperinflation is not associated with poor outcomes after single lung transplant for emphysema. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999;18:1080-1087.

8 Gavazzeni V, Iapichino G, Mascheroni D, et al. Prolonged independent lung respiratory treatment after single lung transplantation in pulmonary emphysema. Chest. 1993;103:96-100.

9 Meade M, Guyatt G, Sinuff T, et al. Trials comparing alternative weaning modes and discontinuation assessments. Chest. 2001;120(6 Suppl):425S-437S.

10 Myles PS. Early extubation after lung transplantation. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1999;13:247-248.

11 Garrity ERJr, Villanueva J, Bhorade SM, et al. Low rate of acute lung allograft rejection after the use of daclizumab, an interleukin 2 receptor antibody. Transplantation. 2001;71:773-777.

12 Hesse CJ, Vantrimpont P, van Riemsdijk-van Overbeeke IC, et al. The value of routine monitoring of mycophenolic acid plasma levels after clinical heart transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2001;33:2163-2164.

13 Cantin B, Giannetti N, Parekh H, et al. Mycophenolic acid concentrations in long-term heart transplant patients: Relationship with calcineurin antagonists and acute rejection. Clin Transplant. 2002;16:196-201.

14 Westall GP, Michaelides A, Williams JT, et al. Bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome and early human cytomegalovirus DNAaemia dynamics after lung transplantation. Transplantation. 2003;75:2064-2068.

15 Weill D, Lock BJ, Wewers DL, et al. Combination prophylaxis with ganciclovir and cytomegalovirus (CMV) immune globulin after lung transplantation: Effective CMV prevention following daclizumab induction. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:492-496.

16 Paya CV. Prevention of fungal infection in transplantation. Transpl Infect Dis. 2002;4(Suppl 3):46-51.

17 Minari A, Husni R, Avery RK, et al. The incidence of invasive aspergillosis among solid organ transplant recipients and implications for prophylaxis in lung transplants. Transpl Infect Dis. 2002;4:195-200.

18 Reichenspurner H, Gamberg P, Nitschke M, et al. Significant reduction in the number of fungal infections after lung-, heart-lung, and heart transplantation using aerosolized amphotericin B prophylaxis. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:627-628.

19 Monforte V, Roman A, Gavalda J, et al. Nebulized amphotericin B prophylaxis for Aspergillus infection in lung transplantation: Study of risk factors. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2001;20:1274-1281.

20 Wimberley SL, Haug MTIII, Shermock KM, et al. Enhanced cyclosporine-itraconazole interaction with cola in lung transplant recipients. Clin Transplant. 2001;15:116-122.

21 Latronico N, Fenzi F, Recupero D, et al. Critical illness myopathy and neuropathy. Lancet. 1996;347:1579-1582.

22 Ost D, Corbridge T. Independent lung ventilation. Clin Chest Med. 1996;17:591-601.

23 Pereszlenyi A, Lang G, Steltzer H, et al. Bilateral lung transplantation with intra- and postoperatively prolonged ECMO support in patients with pulmonary hypertension. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;21:858-863.

24 Meyers BF, Sundt TMIII, Henry S, et al. Selective use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation is warranted after lung transplantation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;120:20-26.

25 Nguyen DQ, Kulick DM, Bolman RMIII. Temporary ECMO support following lung and heart-lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2000;19:313-316.

26 Miniati DN, Robbins RC. Mechanical support for acutely failed heart or lung grafts. J Card Surg. 2000;15:129-135.

27 Zenati M, Pham SM, Keenan RJ, et al. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for lung transplant recipients with primary severe donor lung dysfunction. Transpl Int. 1996;9:227-230.

28 Francalancia NA, Aeba R, Yousem SA, et al. Deleterious effects of cardiopulmonary bypass on early graft function after single lung allotransplantation: Evaluation of a heparin-coated bypass circuit. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1994;13:498-507.

29 Alvarez A, Algar J, Santos F, et al. Airway complications after lung transplantation: A review of 151 anastomoses. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2001;19:381-387.

30 Sarsam MA, Yonan NA, Beton D, et al. Early pulmonary vein thrombosis after single lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1993;12:17-19.

31 Malden ES, Kaiser LR, Gutierrez FR. Pulmonary vein obstruction following single lung transplantation. Chest. 1992;102:645-647.

32 Clark SC, Levine AJ, Hasan A, et al. Vascular complications of lung transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:1079-1082.

33 Despotis GJ, Karanikolis M, Triantafillou AN, et al. Pressure gradient across the pulmonary artery anastomosis during lung transplantation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1995;60:630-634.

34 Michel-Cherqui M, Brusset A, Lui N, et al. Intraoperative trans-esophageal echocardiographic assessment of vascular anastomoses in lung transplantation: A report on 18 cases. Chest. 1997;111:1229-1235.

35 Ross DJ, Vassolo M, Kass R, et al. Transesophageal echocardiographic assessment of pulmonary venous flow after single lung transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1993;12:689-694.