Chapter 65 Lung Cancer

Epidemiology, Surgical Pathology, and Molecular Biology

Epidemiology

Incidence and Survival

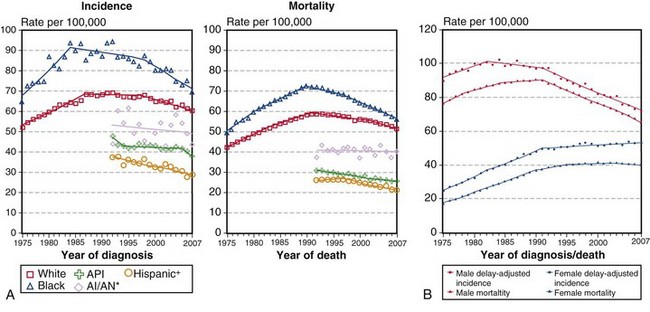

When the mortality rates (deaths due to disease within a calendar year) for lung cancer in women and men are plotted against the calendar years for the last 50 years, one notes a marked difference in the pattern of the curves (Figure 65-1). The incidence rates for men show a marked rise from the early 1950s to the beginning of the 1990s, whereas rates for women lag by about a quarter of a century and then show an identical rise, essentially parallel to those for men, and continuing into the 21st century. By the 1950s, death due to lung cancer far exceeded prostate and colon cancer deaths among men, and by 1990, lung cancer deaths among women exceeded breast and gynecologic cancer deaths. Usually cancer mortality follows cancer incidence; however, in the case of lung cancer, owing to the very high cancer fatality rate (mortality from cancer for persons given a diagnosis of cancer), lung cancer mortality exceeds the most common cancers in both men and women. As a result of the Surgeon General’s 1964 report on smoking, men began to stop smoking in the succeeding 20 to 30 years; the incidence and mortality of lung cancer began to decline from a peak in the early 1990s to a level that approximates the mortality rate of the 1970s. The phenomenon of social smoking among women lagged behind that for men; subsequently, both the incidence of lung cancer in women and its associated mortality continue to rise into the present day.

(A, Incidence data for whites and blacks are from the SEER nine areas—San Francisco, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, Seattle, Utah, Atlanta. Incidence data for Asian/Pacific Islanders, American Indians/Alaska Natives, and Hispanics are from the SEER thirteen areas—the SEER nine areas plus San Jose–Monterey, Los Angeles, Alaska/Native Registry, and Rural Georgia. Mortality data are from U.S. mortality files, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. Rates are age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population [19 age groups, Census P25-1103]. Regression lines are calculated using the Joinpoint Regression program Version 3.4.3, April 2010, National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint analyses for whites and blacks during the 1975-2007 period allow a maximum of 4 joinpoints. Analyses for other ethnic groups during the period 1992 to 2007 allow a maximum of 2 joinpoints. *Rates for American Indians/Alaska Natives are based on the contract health service delivery area [CHSDA] counties. †Hispanic is not mutually exclusive of whites, blacks, Asians/Pacific Islanders, and American Indians/Alaska Natives. Incidence data for Hispanics are based on the NHIA [North American Association of Central Cancer Registries/NAACCR Hispanic Identification Algorithm] and exclude cases from the Alaska Native Registry. Mortality data for Hispanics exclude cases from Connecticut, the District of Columbia, Maine, Maryland, Minnesota, New Hampshire, New York, North Dakota, Oklahoma, and Vermont. B, Data from SEER nine areas and U.S. mortality files [National Center for Health Statistics, CDC]. Rates are age-adjusted to the 2000 U.S. standard population [19 age groups, Census P25-1103]. Regression lines are calculated using the Joinpoint Regression Program Version 3.4.3, April 2010, National Cancer Institute [http://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html].

Surgical Pathology and Cytopathology

Adenocarcinoma

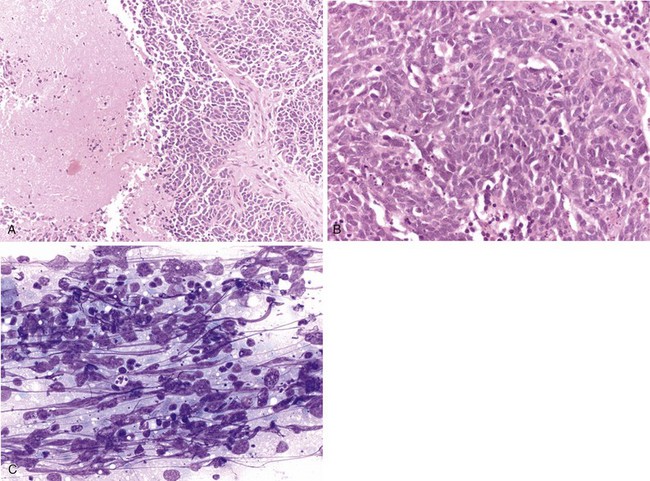

Adenocarcinomas are tumors that produce malignant-appearing glands with tubular, acinar, or papillary differentiation and whose cells may demonstrate mucin production and secretion (Box 65-1). On gross examination, the tumors may manifest peripherally with pleural retraction (puckering), as central or endobronchial masses, as diffuse pleural involvement resembling a malignant mesothelioma, arising or associated with a scar, or as a diffuse parenchymal pneumonic-like tumor. The histologic pattern and organization may show a well-differentiated acinar pattern with intracytoplasmic vacuoles or more poorly differentiated features with solid malignant growth pattern and minimal mucin expression, as demonstrated by histochemical and/or immunohistochemical staining assays. In some cases, the intracytoplasmic vacuole distends the cytoplasm and compressively deforms the nucleus to the cell margin, forming a “signet-ring” cell. The tumors may arise at various levels of the airway with malignant changes in respiratory, bronchiolar, and alveolar epithelium. Malignant transformation of these various epithelia may be associated with protean histologic and cytologic characteristics and growth patterns of invasion.

Box 65-1

Classification of Adenocarcinoma in Resected Specimens

Modified from Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, et al: International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma, J Thorac Oncol 6:244–285, 2011.

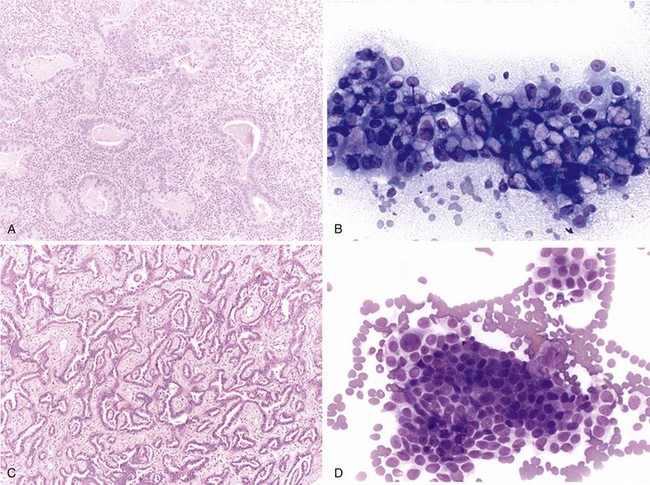

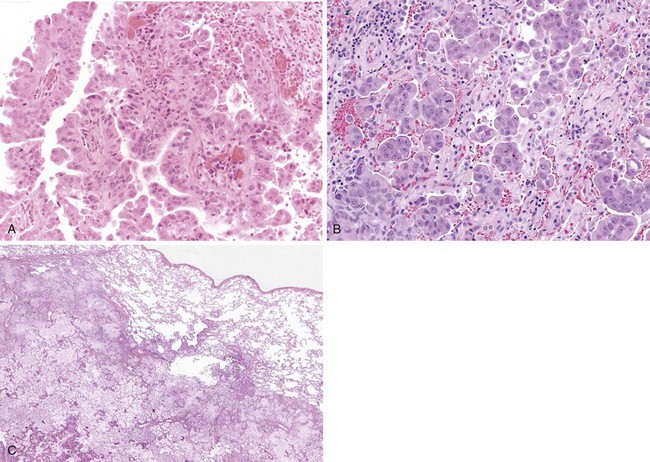

The nature of tumor growth and progression depends on whether the cell of origin is a bronchial gland, ciliated columnar cell, goblet cell, nonciliated bronchiolar cell, or type II pneumocyte. The histologic growth pattern may show a mixture of various types including acinar, papillary, solid, and lepidic (growth along alveolar interstitium), and the cytologic features may include mucinous and nonmucinous differentiation (Figures 65-2 and 65-3). The grading of adenocarcinomas is based on the histopathologic assessment of the extent of glandular differentiation and architectural pattern, cytologic expression and pleomorphism, nuclear characteristics and stratification, and mitotic activity and tumor necrosis. Most adenocarcinomas tend to be of mixed pattern, are intermediate in differentiation or moderately differentiated, and show a predominant acinar-type glandular arrangement. As expected, predominantly solid adenocarcinomas tend to demonstrate high-grade, poorly differentiated cytologic features with prominent mitotic activity and tumor necrosis. Adenocarcinomas may have clear cell features resulting from the accumulation of intracellular glycogen or mucins, and such tumors must be differentiated from metastatic clear cell renal carcinomas; the presence of intracytoplasmic lipid and glycogen is diagnostic of renal tumors of the clear cell type.

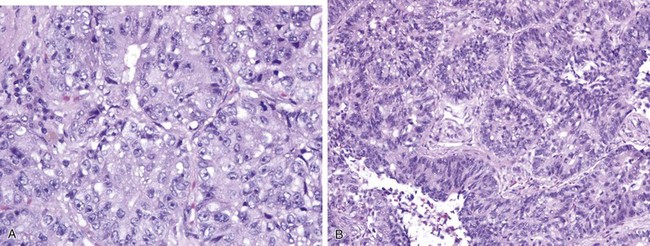

Squamous Cell Carcinoma

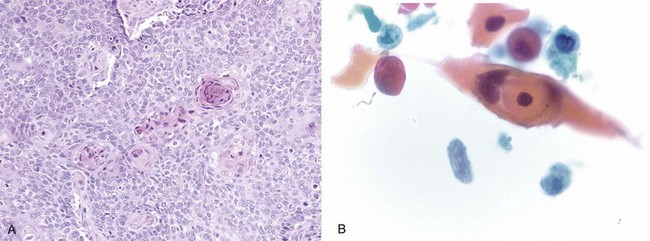

Squamous cell carcinoma is a malignant tumor arising from bronchial epithelium with a strong etiologic association with cigarette smoking, in contrast with adenocarcinoma. It most commonly is central in location and arises from the main, lobar, or segmental bronchi. Squamous cell carcinomas usually appear as white or gray masses with a variable degree of fibrosis, frequently associated with central necrosis and cavitations. Histologic hallmarks of squamous origin, namely keratinization and intercellular bridges, are seen in relation to the degree of the differentiation; although readily appreciated in well-differentiated tumors, they may be only focally present or even absent in poorly differentiated ones (Figure 65-4). In selected cases, when squamous nature cannot be ascertained by routine light microscopy, immunohistochemistry studies are invaluable. Squamous cell carcinomas usually are immunoreactive for high-molecular-weight keratin, CK5/6, and p63 and generally are nonreactive for TTF-1, CK7, and neuroendocrine markers (CD56, synaptophysin, chromogranin). Although not widely used, electron microscopy also can highlight features of squamous differentiation, such as prominent desmosomes and cytoplasmic aggregates of intermediate keratin filaments.

Small Cell Carcinoma and Neuroendocrine (Carcinoid) Tumors

Neuroendocrine tumors, those that contain dense core neurosecretory granules composed of serotonin, histamine, and other bioactive amines, include small cell and large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas and typical and atypical carcinoid tumors. As a group, these tumors represent about one fifth of primary lung neoplasms, with small cell carcinoma being the most common in this category. These tumor types share a histologic pattern of uniform to pleomorphic cells in an organoid arrangement of tumor nests and trabecula (Figure 65-5). Carcinoid tumors may be considered as well-differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas with little to no mitotic activity (less than 2 mitotic figures per 2-mm2 microscopic field) or tumor necrosis. Carcinoid tumors may occur in nonsmokers, in whom they manifest as a vascular rich endobronchial mass, although some carcinoid tumors may have a peripheral localization and have spindle cellular features. The tumors are low-grade malignancies with approximately 15% nodal metastases at diagnosis; nevertheless, affected patients have a greater than 90% 5-year survival. The atypical carcinoid tumors are neuroendocrine carcinomas of intermediate grade that have an organoid arrangement with more irregular and atypical cytologic pattern, identifiable tumor necrosis, and countable mitotic activity (2 to 10 mitoses per 2-mm2 microscopic field). In contrast with typical carcinoid tumors, atypical carcinoid may have nearly 50% lymph node metastases on presentation and a lower 5-year survival rate.

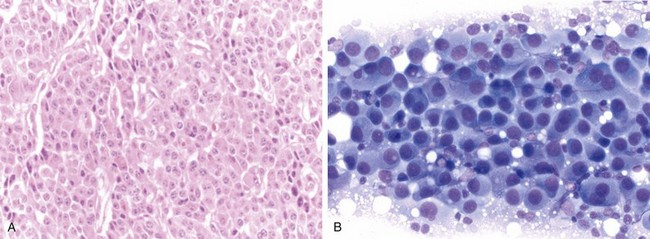

The key histopathologic features in the diagnosis of small cell carcinoma are nuclear morphologic features, such as finely granular chromatin, absence of prominent nucleoli, fragility, molding, and extensive crush artifact, as well as indistinct cytoplasmic borders and high mitotic figure count (more than 10 per 10 high-power fields) (Figure 65-6). Large zones of geographic necrosis also are common. Classically, a great deal of emphasis was placed on the small cell size or nuclear size, as suggested by the nomenclature. The usefulness of this criterion is questionable, however, in view of the wide variability in size, with frequent overlap with large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas. Large cell neuroendocrine carcinomas show a low-power neuroendocrine architecture, as seen in carcinoid tumors; however, the cell morphology closely resembles that of non–small cell carcinomas, with vesicular chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and abundant cytoplasm—features completely different from those of small cell carcinoma (Figure 65-7). Additionally, these tumors are highly mitotic (more than 10 mitotic figures per 10 high-power fields) and often show extensive necrosis, similar to that in small cell carcinomas, and in keeping with their high-grade nature.

Large Cell Carcinoma

By definition, large cell carcinoma of lung is an undifferentiated carcinoma lacking morphologic evidence of small cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, or adenocarcinoma. In other words, it represents a diagnosis of exclusion. These tumors typically are composed of sheets and nests of large polygonal cells with moderate amount of cytoplasm, vesicular chromatin and prominent nucleoli (Figure 65-7). Although the classification is purely based on morphologic grounds, judicious use of ancillary studies (as discussed previously), especially with small biopsy specimens, is of significant value in separating the poorly differentiated squamous cell carcinomas and adenocarcinomas from the truly undifferentiated large cell carcinoma. These tumors share similar demographic and clinical features with other non–small cell carcinomas of the lung, because they commonly are seen in elderly men with smoking history.

Alberg AJ, Samet JM. Epidemiology of lung cancer. Chest. 2003;123:21S–49S.

American Cancer Society. 2010 Cancer facts & figures. Atlanta: American Cancer Society; 2010.

Brambilla E, Gazdar A. Pathogenesis of lung cancer signalling pathways: roadmap for therapies. Eur Respir J. 2009;33:1485–1497.

Cadranel J, Zalcman G, Sequist L. Genetic profiling and epidermal growth factor receptor directed therapy in non-small cell lung cancer. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:183–193.

Camidge DR, Hirsch FR, Varella-Garcia M, Franklin WA. Finding ALK-positive lung cancer: what are we really looking for? J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:411–413.

Han SW, Kim TY, Hwang PG, et al. Predictive and prognostic impact of epidermal growth factor receptor mutation in non-small cell cancer patients treated with gefitinib. J Clin Oncol. 23, 2005. 2493–2402

Haura EB, Camidge DR, Reckamp K, et al. Molecular origins of lung cancer: prospects for personalized prevention and therapy. J Thorac Oncol. 2010;5:S207–S213.

Husain AN, Colby TV, Ordonez NG, et al. Guidelines for pathologic diagnosis of malignant mesothelioma. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133:1317–1331.

Idowu M, Powers CN. Lung cancer cytology: potential pitfalls and mimics—a review. J Clin Exp Pathol. 2010;3:367–385.

Inamura K, Takeuchi K, Togashi Y, et al. EML4-ALK fusion is linked to histologic characteristics in a subset of lung cancers. J Thorac Oncol. 2008;3:13–17.

Mitsudomi T, Kosaka T, Endoh H, et al. Mutations of the epidermal growth factor receptor gene predict prolong survival after gefitinib treatment in patients with non-small-cell lung cancer with postoperative recurrence. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:2513–2520.

Mok TS, Wu YL, Thongprasert S, et al. Gefitinib or carboplatin-paclitaxel in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:947–957.

Osann KE. Lung cancer in women: the importance of smoking, family history of lung cancer, and medical history of respiratory disease. Cancer Res. 1991;51:4893–4897.

Rekhtman N. Neuroendocrine tumors of the lung. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2010;134:1628–1638.

Rekhtman N, Brandt SM, Sigel CS, et al. Suitability of thoracic cytology for new therapeutic paradigms in non-small cell lung carcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:451–458.

Samet J, Humble C, Pathak D. Personal and family history of respiratory disease and lung cancer risk. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986;134:466–470.

Schwartz AM, Henson DE. Diagnostic surgical pathology in lung cancer: ACCP evidence-based clinical practice guidelines, ed 2. Chest. 2007;132:78–91.

Shaw AT, Yeap BY, Mino-Kenudson M, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with non-small cell lung cancer who harbor EML4-ALK. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:4247–4251.

Soda M, Choi YL, Enomoto M, et al. Identification of the transforming EML4-ALK fusion gene in non-small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2007;448:561–566.

Takano T, Ohe Y, Sakamoto H, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor gene mutations and increase copy numbers predict gefitinib sensitivity in patients with recurrent non-small cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:6829–6837.

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Muller-Hermelink HK, et al. Pathology and genetics. Tumors of the lung, pleura, thymus, and heart. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2004.

Travis WD, Brambilla E, Noguchi M, et al. International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer/American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:244–285.

U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. How tobacco smoke causes disease: the biology and behavioral basis for smoking attributable disease: a report of the Surgeon General. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office of Smoking and Health; 2010.

U.S. Public Health Service Smoking and health. Report of the Advisory Committee to the Surgeon General. PHS publication no. 1103. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Public Health Service, CDC; 1964.