Lung Abscess

After reading this chapter, you will be able to:

• List the anatomic alterations of the lungs associated with lung abscess.

• Describe the causes of lung abscess.

• List the cardiopulmonary clinical manifestations associated with lung abscess.

• Describe the general management of lung abscess.

• Describe the clinical strategies and rationales of the SOAPs presented in the case study.

• Define key terms and complete self-assessment questions at the end of the chapter and on Evolve.

Anatomic Alterations of the Lungs

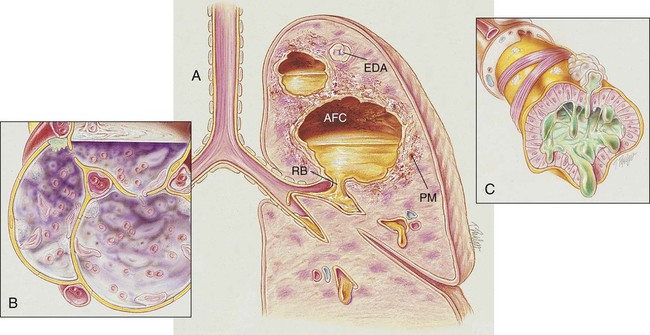

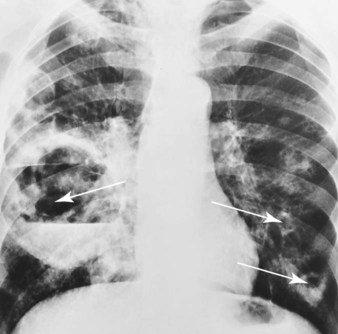

During the early stages of a lung abscess, the pathology is indistinguishable from that of any acute pneumonia. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes and macrophages move into the infected area to engulf any invading organisms. This action causes the pulmonary capillaries to dilate, the interstitium to fill with fluid, and the alveolar epithelium to swell from the edema fluid. In response to this inflammatory reaction, the alveoli in the infected area become consolidated (see Figure 15-1).

As the inflammatory process progresses, tissue necrosis involving all the lung structures occurs. In severe cases the tissue necrosis ruptures into a bronchus and allows a partial or total drainage of the liquefied contents into the cavity. An air- and fluid-filled cavity also may rupture into the intrapleural space via a bronchopleural fistula and cause pleural effusion and empyema (see Chapter 23, Pleural Diseases). This may lead to inflammation of the parietal pleura, chest pain, atelectasis, and decreased chest expansion. After a period of time, fibrosis and calcification of the tissues around the cavity encapsulate the abscess (see Figure 16-1).

The major pathologic or structural changes associated with a lung abscess are as follows:

Etiology and Epidemiology

A lung abscess is commonly associated with the aspiration of gastric and oral fluids. Aspiration can cause either (1) chemical pneumonia, (2) anaerobic bacterial pneumonia, or (3) a combination of both (see Chapter 15). The aspiration of acidic gastric fluids is associated with immediate injury to the tracheobronchial tree and lung parenchyma—often likened to a flash burn. Common anaerobic organisms found in the normal flora of the mouth, upper respiratory tract, and gastrointestinal tract include the following:

Box 16-1 on p. 247 summarizes organisms known to cause lung abscess.

General Management of Lung Abscess

Medications and Procedures Commonly Prescribed by the Physician

Antibiotics

When lung abscesses are caused by methicillin-susceptible strains of Staphylococcus aureus, nafcillin or oxacillin (with or without rifampin) may be used. In the case of methicillin-resistant strains of S. aureus, vancomycin (with or without rifampin) is commonly administered. Good alternative choices are cephalosporins and clindamycin. (See Appendix III, Antibiotics.)

Respiratory Care Treatment Protocols

Oxygen Therapy Protocol

Oxygen therapy is used to treat hypoxemia, decrease the work of breathing, and decrease myocardial work. The hypoxemia that develops in lung abscess is usually caused by pulmonary capillary shunting. Hypoxemia caused by capillary shunting is often refractory to oxygen therapy (see Oxygen Therapy Protocol, Protocol 9-1).

Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol

Because of the excessive mucous production and accumulation associated with a ruptured lung abscess, a number of bronchial hygiene treatment modalities may be used to enhance the mobilization of bronchial secretions (see Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol, Protocol 9-2).

CASE STUDY

Lung Abscess

Admitting History and Physical Examination

Respiratory Assessment and Plan

S “I can’t stop coughing.” Complains of low-grade fever, loss of appetite, weight loss (6 lb).

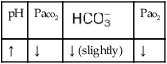

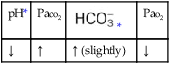

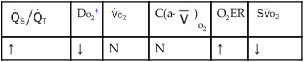

O Cachectic. BP 160/90, HR 120, RR 22, T 100.6° F orally. Teeth carious. Flat to percussion over RLL. Crackles, rhonchi, and bronchial breath sounds over RLL. CXR: 4-cm diameter cavity with fluid level and consolidation RLL. ABGs: pH 7.51, Paco2 29,  22, and Pao2 61. Excessive amount of foul-smelling, thick brown and gray sputum.

22, and Pao2 61. Excessive amount of foul-smelling, thick brown and gray sputum.

• Lung abscess and consolidation, RLL (CXR)

• Acute alveolar hyperventilation with mild hypoxemia (ABG)

P Oxygen Therapy Protocol: 2 L/min per nasal cannula. Spo2 spot check to verify appropriateness of O2 therapy. O2 titration if necessary. Bronchopulmonary Hygiene Therapy Protocol: Deep breathe and cough, with postural drainage to right lower lobe q6h. Aerosolized Medication Protocol: Trial period of med nebs: 2.0 cc acetylcysteine with 0.5 mL albuterol  hour before postural drainage q6h × 3 days, then reevaluate.

hour before postural drainage q6h × 3 days, then reevaluate.

Discussion

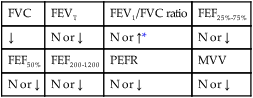

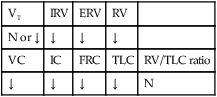

This case illustrates some of the classic clinical manifestations of a lung abscess. For example, the Alveolar Consolidation (see Figure 9-9), which was identified on the chest x-ray film, surrounding the abscess likely played a role in producing the patient’s fever and increased heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate. In addition, the pneumonic consolidation also contributed to the patient’s alveolar hyperventilation and hypoxemia, the bronchial breath sounds, and the reduced lung volumes and capacities and flow rates identified on his PFT.

In addition, the clinical manifestations associated with Excessive Bronchial Secretions (see Figure 9-12) also were seen in this case. Not only did the excessive airway secretions contribute to the patient’s hypoxemia, secondary to the decreased  ratio and pulmonary shunting, but they also contributed to the increased airway resistance (caused by the secretions) that resulted in the rhonchi, sputum production, and reduced air-flow rates seen in the PFT.

ratio and pulmonary shunting, but they also contributed to the increased airway resistance (caused by the secretions) that resulted in the rhonchi, sputum production, and reduced air-flow rates seen in the PFT.

The primary treatments started by the respiratory care practitioner were directed to the patient’s excessive secretions. Lung Expansion Therapy (see Protocol 9-3) was not employed in this case. One could argue that it should have been, given the chest x-ray film infiltrates, which could have represented atelectasis just as well as pneumonia. The appropriate respiratory care of patients with lung abscesses closely resembles that of those with bronchiectasis (see Chapter 13). Identification of this patient’s lung abscess in the right lower lobe allowed targeted chest physical therapy to be practiced. The suggestion that a Social Service representative see the patient to instruct him regarding his personal hygiene was entirely appropriate. Finally, extraction of his carious teeth was suggested by the Dental Service, hopefully, to eradicate this source of infection once and for all.

values will be lower than expected for a particular Pa

values will be lower than expected for a particular Pa

)

)

)O2, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;

)O2, Arterial-venous oxygen difference; DO2, total oxygen delivery; O2ER, oxygen extraction ratio;  , pulmonary shunt fraction;

, pulmonary shunt fraction;  mixed venous oxygen saturation;

mixed venous oxygen saturation;  oxygen consumption.

oxygen consumption.

22, and Pa

22, and Pa