21 Lumps in the groin and hernia

Case

A 69-year-old man presents with a mass to the left of his umbilicus. He had noted this would come up when he stood or if he coughed or strained. The mass was getting progressively larger over the previous 4 or 5 months. There was no recent history of abdominal pain, constipation, vomiting or abdominal distension. He did not have a chronic cough. Eighteen months earlier he had an anterior resection for a Dukes’ C carcinoma of the distal sigmoid colon, followed by a course of adjuvant chemotherapy. He was otherwise fit and well.

Introduction

The complaint of ‘a lump in the groin’ is commonly encountered in general clinical practice. The causes of this complaint are listed in Box 21.1. In the vast majority of cases, the cause is a hernia. The key clinical differentiation usually required is between a hernia and an enlarged inguinal lymph node. If a hernia is the problem, the clinician then has to decide whether it is inguinal or femoral.

History

The painless lump

The lump in the groin may have been a chance finding by the patient and may not be associated with symptoms. Each of the conditions listed in Box 21.1 may present as a painless lump. Indeed, pain does not occur with a saphena varix, lipoma of the cord, encysted hydrocoele of the cord, hydrocoele of the canal of Nuck, or testicular maldescent. Hernias, inguinal lymphadenopathy and femoral aneurysms may or may not be associated with pain. Historically, the development of a hernia may have been preceded by groin pain after a heavy lift or ‘strain’. However, many hernias appear without any such antecedent history.

The painful lump

Hernias can be associated with several types of pain.

Incarceration of the contents of a hernia within a hernial sac may be associated with intestinal obstruction, which is more commonly small bowel than large bowel. Small bowel obstruction is associated with central abdominal colicky pain, vomiting, abdominal distension and constipation (Ch 4).

Physical Examination

Anatomical localisation of the lump

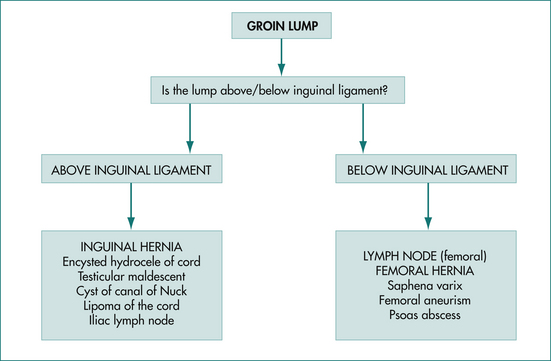

Figure 21.1 details the various groin lumps above and below the inguinal ligament.

Lumps in the inguinal region (above inguinal ligament)

Inguinal hernias

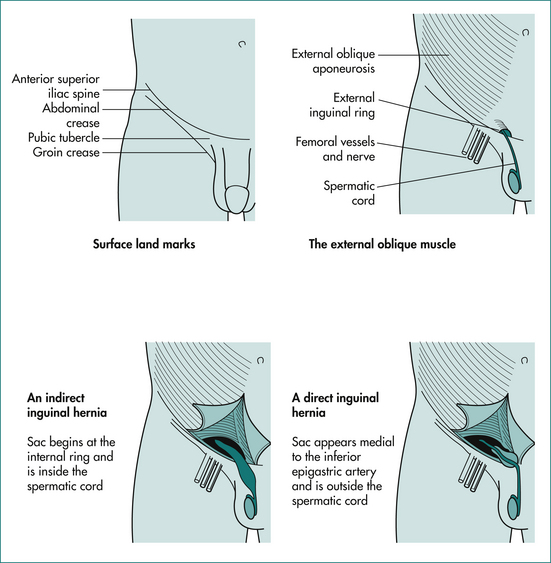

Inguinal hernias exit from the abdominal cavity and then pass along the inguinal canal together with the spermatic cord in the male. The inguinal canal passes medially from the deep inguinal ring, the surface marking of which is the midinguinal point (see above) to the superficial inguinal ring, which is just above and medial to the pubic tubercle (Fig 21.2).

Figure 21.2 Anatomy of the inguinal region and important landmarks.

From Browne NL. An introduction to the symptoms and signs of surgical disease. 3rd edn. New York: Oxford University Press; 1977.

It is imperative to examine the patient complaining of a lump in the groin while the patient is standing because a hernia may be apparent only in this position. Having examined in the standing position, have the patient lie down and determine if the hernia is reducible—coughing should also cause it to return. By placing the fingers along the line of the inguinal canal and asking the patient to cough, a cough impulse may be elicited; this is a pathognomonic sign of an inguinal hernia. This sign refers to the sudden expansion of a bulge beneath the examining fingers, which occurs when the increase of intraabdominal pressure blows some of the intraabdominal contents out into the hernial sac. If the examiner believes that the sign has been elicited, then it is worth trying to elicit the sign on the contralateral side for two reasons. First, inguinal hernias are not uncommonly bilateral. Secondly, the cough impulse of a hernia can be confused with a normal anterior movement of the whole of the lower anterior abdominal wall anteriorly with coughing. This anterior movement is not expansile.

Direct and indirect inguinal hernias

Inguinal hernias are defined as direct or indirect (Fig 21.2). With a direct hernia, the hernial sac enters the inguinal canal through a weakness in the tissues of the posterior wall of the inguinal canal. With an indirect hernia, the sac enters the inguinal canal through the deep inguinal ring. The distinction between the two types of inguinal hernias is of little practical importance. From the prognostic point of view, indirect hernias more commonly develop the complication of strangulation (a strangulated hernia is one in which the contents are ischaemic) as the neck is narrower. Indirect hernias more commonly pass down into the scrotum than do direct hernias. Direct inguinal hernias are more commonly bilateral and have a wider neck.

Reducible or irreducible?

An encysted hydrocoele of the cord within the inguinal canal should be suspected if traction on the ipsilateral testis causes the lump to move medially along the inguinal canal. An encysted hydrocoele of the cord distal to the superficial inguinal ring should be suspected on clinical examination by the presence of a transilluminable swelling in close proximity to the spermatic cord; this does not extend laterally into the superficial inguinal ring, making differentiation from an inguinal hernia relatively easy. If there is any doubt about the diagnosis of an encysted hydrocoele of the cord and a hydrocoele of the canal of Nuck, then the diagnosis can be confirmed by an ultrasound examination.

Lumps in the femoral region (below inguinal ligament)

Figure 21.1 details the various groin lumps below the inguinal ligament.

Anatomy of the femoral region

The femoral region is inferior to the inguinal ligament. The reference point in the femoral region is the femoral artery, which is located inferior to the midinguinal point as a pulsatile longitudinal cord. Deep to the femoral artery is the psoas muscle, which passes posteriorly to attach to the lesser trochanter of the femur. Lateral to the femoral artery is the femoral nerve. Medial to it is the femoral vein into which drains the long saphenous vein. Medial to the femoral vein is the femoral canal through which a femoral hernia emerges from the abdominal cavity. The femoral canal usually contains just fatty tissue and a few tiny lymph nodes. Within the femoral region are the inguinal lymph nodes. They are divided into two groups, deep and superficial, depending on whether they are deep or superficial to the deep fascia. The deep group lie around the femoral vein. The superficial group are placed horizontally just below and parallel to the inguinal ligament or vertically along the line of the long saphenous vein.

Physical examination of the femoral region

Diagnosis remains uncertain

The next step is to carefully examine the area drained by the inguinofemoral nodes as well as the reticuloendothelial system in general, as the enlarged lymph node may be part of a more generalised disease (e.g. lymphoma). As part of such a ‘lymphatic look’ it is vital to look carefully for a focus of infection or neoplasia as well as for any old scars that may represent a previously excised tumour. Boxes 21.2 and 21.3 list all of the areas that should be included in your ‘lymphatic look’.

An ultrasound may help to further define the nature of the lump.

Management of Groin Lumps

Management of femoral and inguinal hernias

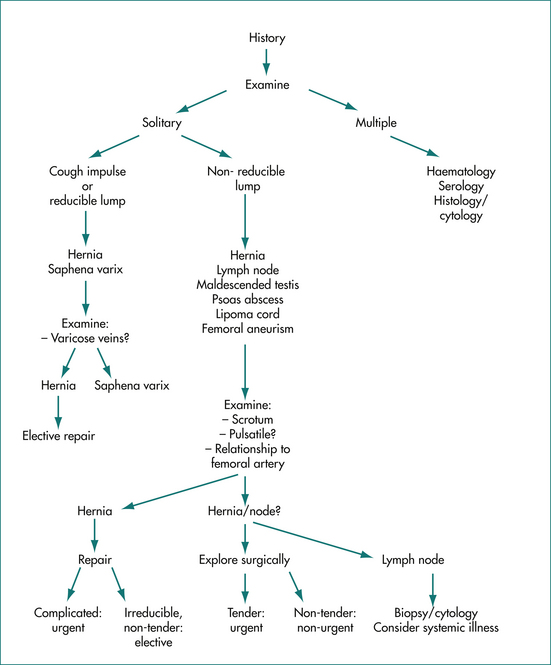

The preferred method of treatment is surgical repair (either open surgery or laparoscopic), the only method to cure an inguinal or a femoral hernia (see Fig 21.3). This has the benefit of relieving the inconvenience or discomfort of the hernia and, at the same time, preventing complications. Technically speaking, the hernia is always better to repair when it is small.

Management of an enlarged lymph node

An enlarged inguinal lymph node may be solitary, associated with other enlarged lymph nodes in the groin or associated with a more generalised process of the lymphatic system (see Fig 21.3).

Generalised lymphadenopathy

If the cause is not found by non-invasive investigations, then surgical biopsy may be required. Nodes other than inguinal lymph nodes are usually biopsied as non-specific inflammatory changes are commonly found in inguinal lymph nodes of normal patients.

Key Points

Avisse C., Delattre J.F., Flament J.B. The inguinal rings. Surg Clin North Am. 2000;80:49-69.

Corder A.P. The diagnosis of femoral hernia. Postgrad Med J. 1992;68:26-28.

Kingsnorth A., LeBlanc K. Hernias: inguinal and incisional. Lancet. 2003;362:1561-1571.

McIntosh A., Hutchinson A., Roberts A., et al. Evidence-based management of groin hernia in primary care—a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2000;17:442-447.

Oishi S.N., Page C.P., Schwesinger W.H. Complicated presentations of groin hernias. Am J Surg. 1991;162:568-570.

Talley N.J., O’Connor S. Clinical examination, 6th edn. Sydney: Churchill Livingstone; 2010.