Lumbar Spine Fusion

Chris Izu, Haideh V. Plock, Jessie Scott and Paul Slosar, Adam Cabalo

In the early 1900s two surgeons began performing lumbar fusions. Dr. Russell Hibbs and Dr. Fred Albee pioneered the posterior approaches for arthrodesis.1,2 Over the subsequent decades, many surgeons improved fusion techniques, with extension of the fusion laterally to incorporate the transverse processes and the sacral ala.3–6 The patient’s autogenous iliac crest is the standard source of bone graft material.7,8 A rapid evolution has occurred in the development and use of spinal fixation devices. Although tracing the historical evolution of these devices is beyond the scope of this chapter, they can simply be categorized as anterior or posterior fixation devices. The most common and most controversial are the pedicle screw and rod/plate systems. Anterior fixation devices include screw and rod/plate systems, as well as the recently introduced interbody cages. This chapter describes the indications for elective lumbar fusions and discusses the various methods of arthrodesis.

Surgical Indications and Considerations

In the elective patient population, most indications for lumbar arthrodesis are based on the presence of severe, disabling back or leg pain. Posttraumatic cases of segmental instability or potential neurologic injury also may require fusions, but this chapter focuses on patients with degenerative spinal pathology.

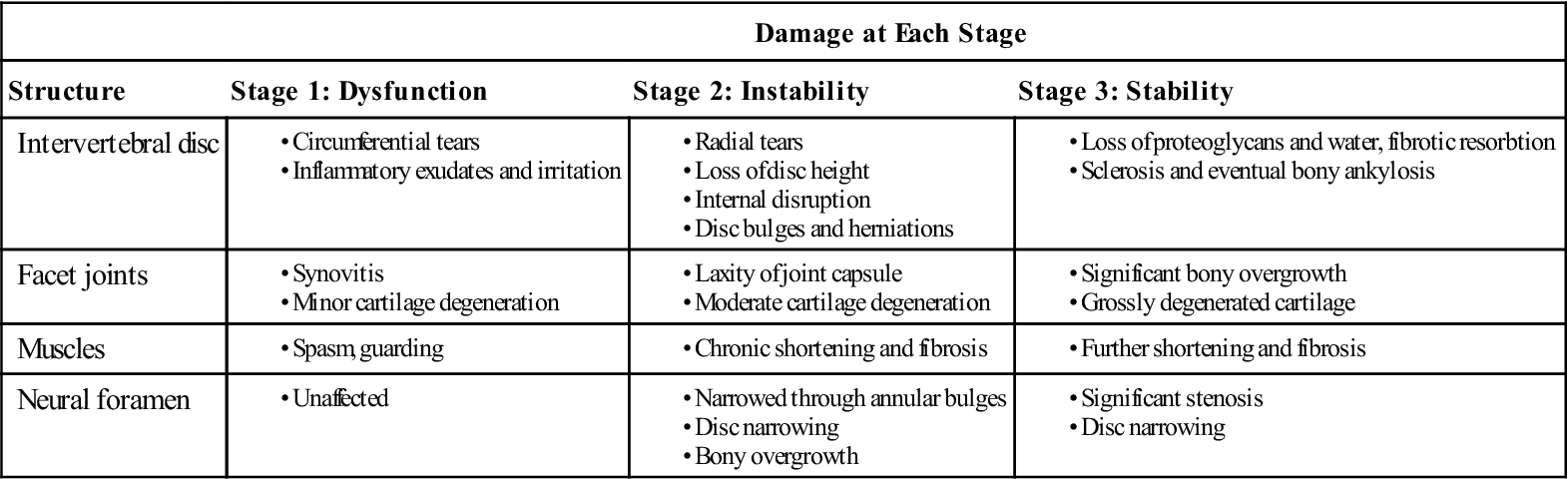

Patients with low back pain experience symptoms resulting from tissue aggravation during the degenerative cascade.9 Trauma or overuse causes the disc wall to begin to develop microtears; this eventually results in a loss of disc height that alters the alignment of the facet joints. This may lead to pain, with accompanying spasm and guarding. The joints begin to develop synovitis, articular cartilage degeneration, and adhesions. This alters the spinal motion mechanics at that segment, further stressing the annulus of the disc and accelerating the degenerative process of the facet. Increased wearing of the cartilage and hypermobility of the facet also occur. The superior and inferior facet surfaces begin to enlarge. As the joint becomes more disrupted, normal motion at that segment becomes impossible. The disc begins to undergo greater strain. The disc wall weakens further, begins to bulge, and can eventually herniate. The disc continues to lose fluid and height, causing narrowing of the neural foramen, or foraminal stenosis. This process is outlined in Table 16-1.

TABLE 16-1

< ?comst?>

| Damage at Each Stage | |||

| Structure | Stage 1: Dysfunction | Stage 2: Instability | Stage 3: Stability |

|

Intervertebral disc

|

|||

|

Facet joints

|

|||

|

Muscles

|

|||

|

Neural foramen

|

|||

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Patients with severe back pain that is refractory to conservative care may be candidates for surgical evaluation. Conservative care should include a rigorous attempt at exercise-based dynamic stabilization training, therapeutic injections, and medications. Surgical treatment should only be discussed with the patient after a firm diagnosis has been made.

Diagnostic Tests

Spinal radiographs show osteophytes and segmental disc space narrowing in patients with degenerative spondylosis. A defect in the pars interarticularis is seen in patients with spondylolysis. Anterolisthesis, or a forward slippage of one vertebra on the next, is the hallmark radiographic finding in spondylolisthesis. Flexion and extension films can help to detect hypermobility or excessive motion in degenerative lumbar conditions.

Computed tomography (CT) reliably evaluates the bone or spondylosis compression against the nerves. Computer-enhanced reformatted CT images are as effective in evaluating spinal stenosis as myelography. CT scanning is more sensitive than magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in the evaluation of bony stenosis, whereas MRI gives useful information about the health of the discs and nerves. Combining the two imaging modalities gives a very accurate, thorough picture of the lumbar spinal pathoanatomy.

Provocative discography can be a useful diagnostic tool in the work-up of patients with painful degenerative lumbar disc disease. The lumbar discs are deep within the abdominal cavity and do not have true dermatomal pain patterns in axial discogenic cases. Overlapping sclerodermal referred pain patterns in the lumbar spine make the localization of the true pain generator difficult. Discography has evolved as a test to examine the lumbar discs morphologically and, most importantly, provocatively. On injection into the disc, the patient must communicate to the discographer if that disc is concordantly painful. Many degenerative discs are either not painful or discordantly painful. This information can be useful for the surgeon and the patient contemplating lumbar arthrodesis. The test is not used as frequently as in the past, as authors have described conflicting results and there is emerging concern that the injection itself may cause eventual disc deterioration.10

Diagnosis

Among patients undergoing elective lumbar arthrodesis, painful degenerative disc disease is the most prevalent diagnosis. Confirmatory diagnostic testing often includes MRI scanning and discography for equivocal cases. Overlap occurs among patients who have had previous surgery and have a diagnosis of “failed back surgery syndrome,” a nonspecific diagnosis. Before surgery is contemplated, every effort must be made to arrive at a diagnosis that specifically isolates the source of pain.

Patients often have numerous diagnoses, each of which may be valid. For example, a 45-year-old man who had a laminotomy performed 5 years ago for a herniated nucleus pulposus comes to his physician complaining of 50% low back pain and 50% right leg pain and numbness. Diagnostic imaging is significant for L4 to L5 segmental degeneration with osteophytes and narrowing of the disc space. A multiplanar CT scan reveals moderate spondylosis (bone spurs) with stenosis along the right neural foramen. Discography is concordant with pain reproduction at the L4 to L5 disc. The appropriate diagnoses include painful degenerative disc disease, lumbar spondylosis with stenosis, and postlaminectomy syndrome.

The absolute requisite for a successful lumbar surgery outcome is matching concordant patient symptoms with the appropriate surgical procedure. Patients who cannot manage their pain with conservative measures and have demonstrable, concordant pathology on diagnostic testing may benefit from lumbar arthrodesis.

Types of Fusions

Instrumentation Versus Noninstrumentation

The goal of a lumbar arthrodesis is the successful union of two or more vertebra. Controversy exists over the most efficient way to achieve this result. Instrumentation can be used to immobilize the moving segments while the fusion becomes solid. One of the original and most popular systems is the Harrington hook/rod construct. Although this distraction type of fixation immobilizes the spine in certain planes, it causes a loss of physiologic lordosis, or a “flat-back syndrome,” in many patients.

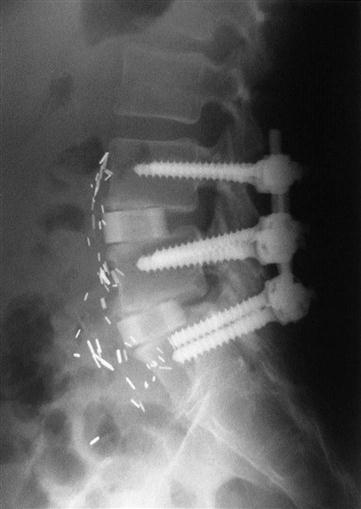

Today, most spine surgeons use pedicle screw constructs to immobilize the vertebrae rigidly while preserving the normal lumbar lordosis2 (Fig. 16-1). Typically, external orthosis bracing is not needed in these cases. As well-controlled studies emerge, data support the use of internal fixation for fusion.11 Most studies support the use of pedicle screw fixation to obtain a more reliable bony union, although complication rates tend to be higher with these devices as well.12,13

Some surgeons do not routinely use pedicle screws for arthrodesis. In most of these situations (when pedicle screws are used) the patient must wear a lumbar orthosis for an extended period postoperatively. To immobilize the L5 to S1 motion segment effectively, an orthosis with a thigh-cuff extension must be applied. Patients with noninstrumented fusions may take an extensive amount of time to stabilize and become comfortable in their rehabilitation. Conversely, most patients with internal fixation become mobile and independent more rapidly, making early rehabilitation more predictable.

Posterior Fusion

Posterolateral Lumbar Fusion

Different surgeons use different techniques to perform a lumbar fusion. The traditional approach is through a midline posterior incision. If necessary the surgeon performs a laminectomy/laminotomy to address the pertinent pathology. Most surgeons perform a posterolateral fusion, which means that the transverse processes, pars interarticularis, and, if needed, the sacral alae are decorticated. The patient’s own iliac crest bone graft or a bone graft substitute is then placed on the decorticated surfaces, forming a fusion bed contiguous with all the surfaces to be fused. Pedicle screws and rods or plates may be placed to immobilize the motion segments rigidly and augment the formation of a solid union.

The problems with a posterolateral fusion are both mechanical and physiologic. The fusion is attempting to form at a mechanical disadvantage because of tension. Bone heals more reliably under protected physiologic loads of compression, not tension. Also, the available area for the bone union to occur is limited to the remaining posterolateral bone surfaces. After extensive decompression of the neural elements (laminectomy), the available fusion area is reduced and often poorly vascularized. These local factors reduce the likelihood of a successful arthrodesis. Nicotine use negatively influences the formation of posterolateral lumbar fusions.

Finally, the usual source of pain in these patients is the disc itself, hence the term discogenic. In routine cases of posterolateral fusions the disc is not radically resected. Biomechanical studies have shown that people bear load through the middle and posterior thirds of the disc. Several reports describe a persistently painful disc under a solid posterior fusion.14 As surgeons recognized the biomechanical and physiologic aspects of the discs, they began performing interbody fusions.15

Interbody Fusion

Posterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion.

Interbody fusions evolved to address many of the drawbacks of traditional posterolateral fusions. Radical excision of the disc and anterior column support with rigid bone grafting are performed. The available area for successful bone union is greatly increased by using the interbody space.

Using a posterior lumbar approach, a surgeon performs a posterior lumbar interbody fusion (PLIF). After a wide laminectomy the posterior two thirds of the disc is resected and an interbody graft is placed into the evacuated disc space. This provides anterior interbody stability through a posterior approach. PLIF is a technically demanding procedure associated with a higher incidence of postsurgical nerve injuries.

Transforaminal Lumbar Interbody Fusion.

In an effort to reduce the incidence of nerve injury performed through a PLIF, a transforaminal lumbar interbody fusion (TLIF) technique was developed. Studies have shown the results of TLIF with posterior pedicle screw instrumentation to be equivalent to that of anterior-posterior fusions with an anterior lumbar interbody fusion (ALIF). However, despite the intention of reducing nerve injury through a transforaminal approach, nerve root injury has been reported as a complication of the procedure.16 In addition to nerve root injury, TLIFs can cause a kyphotic alignment in the lumbar spine.

After exposing the spine through either a midline or paramedian posterior approach, the facet joint and pars interarticularis above the proposed fusion level is resected. This allows access to the posterolateral aspect of the disc. Care is taken to avoid injury to both the existing and transversing nerve root. A standard discectomy and insertion of an interbody device is then performed.

Anterior Lumbar Interbody Fusion.

Because the risks associated with PLIF were too great for routine use, many surgeons moved to ALIF. Using the same principles of disc excision and interbody bone grafting, many surgeons achieved excellent results. However, ALIF alone cannot withstand the forces across the grafts, so many collapse or do not fuse. Surgeons who perform ALIF have learned to protect the grafts with posterior instrumentation, leading to a predictable fusion rate and good clinical results.

From a technical standpoint, anterior lumbar surgery is most easily and safely accomplished through a retroperitoneal approach. After the anterior disc is exposed, it is relatively simple to perform a discectomy and insert the bone graft of the surgeon’s choice. Posterior fusion and instrumentation can be placed through a separate posterior approach on either the same day or in a staged procedure. A circumferential fusion is accomplished in this manner (see Fig. 16-1).

Lateral Interbody Fusion.

An alternative to performing an ALIF is through a lateral interbody approach. The use of a lateral approach avoids the need for exposure of the great vessels and therefore has less potential for vascular injury. However, it does not come without inherent risks, the most notable of which is nerve stretch injury. The most common is an L4 nerve root injury.17 The lateral approach cannot be used for the L5-S1 intervertebral disc as the pelvis blocks access.

With a lateral approach, the disc is accessed through the psoas muscle under neuromonitoring to avoid injury to the lumbar plexus. After gaining access to the disc, a procedure similar to an ALIF is carried out including discectomy and insertion of an interbody graft.

Interbody Cages.

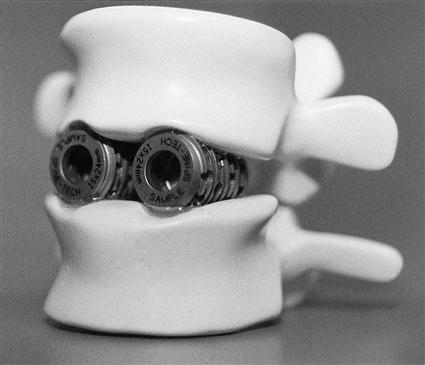

Ongoing technologic advances have been made in interbody cages. Essentially, these devices are hollow cylinders made of titanium, carbon, or bone (Fig. 16-2). They are filled with autogenous bone graft or a bone graft substitute and inserted between the vertebral bodies. Newer devices have implemented bone ingrowth surfaces and large footprint areas to aid in the fusion process and decrease rates of subsidence.

Research is moving rapidly to find a reliable substitute for the autogenous bone graft, most likely with the use of bone-morphogenic protein. There are other biologic alternatives available to surgeons that can be used to fill the interbody fusion cages and reduce the need for bone graft harvest.

Surgical Procedure

The basic lumbar fusion is the posterolateral fusion. The patient is placed in a prone position on a Jackson frame, allowing the abdomen to hang free. This decompresses the lumbar epidural veins and minimizes bleeding. A skin incision is made over the operative levels, and the paraspinal muscles are stripped off the posterior elements (spinous process, lamina, and transverse processes). Deep retractors hold back the muscles to allow the surgeons to expose the bone for fusion. Using small curettes or a high-speed burr, the surgeon decorticates the dorsal aspect of the transverse processes and facet joints in preparation for the bone graft placement. Through a separate fascial incision, the surgeon harvests the necessary amount of cortical and cancellous bone graft from the posterior iliac crest. This bone graft material is then carefully placed in the recipient site.

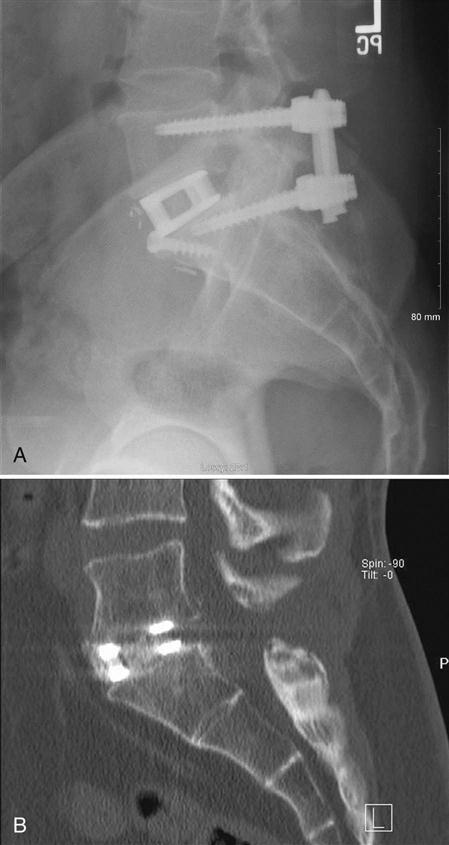

If screws are used to augment the fusion, a pilot hole is made over the entry site of the pedicle with a burr (Fig. 16-3). Usually probes are placed in the pedicles and a radiograph is taken to confirm the position of the pedicle probes. After confirmation, the pedicles are tapped and appropriate length screws are placed into the pedicles. Again, an intraoperative radiograph is taken to confirm the position of the screws. The rods or plates are connected to the screws, and lordosis is preserved in the construct. The wound is usually irrigated with an antibiotic solution to minimize the chance of infection and closed over a deep suction drain. The drain is removed when the postsurgical drainage is minimal. Patients are mobilized out of bed as tolerated on the first or second day after surgery.

Therapy Guidelines for Rehabilitation

Description of Rehabilitation and Rationale for Using Instrumentation

Opinion about the degree of rehabilitation needed after spinal surgery ranges from the optimistic view that no rehabilitation is needed to others who argue for aggressive exercise- and education-based programs. As noted earlier there has also been mounting evidence that failing to address psychosocial factors in this population may also be neglecting an integral part of the rehabilitation and recovery process. This chapter is written from the point of view that the patient who has undergone surgery needs not only a program that will protect the surgical area and create an effective healing environment, but also addresses relevant and contributing changes in motor control dealing with both the active subsystems and neural control subsystems as outlined by Panjabi18,19 (Box 16-1). Although the surgery itself deals with improving the passive subsystem, which include such anatomic structures as the vertebral bodies, facets, and ligaments, capsule, it is our job as specialists in rehabilitation to address these other systems.20 It is also important to realize that those individuals with more chronic pain symptoms will most likely exhibit altered pain processing, which may be addressed through including cognitive-behavioral interventions during the recovery process.

The following guidelines are not intended to substitute for sound clinical reasoning but rather serve as a foundation on which a trained physical therapist (PT) can base the rehabilitation of a patient after spinal fusion. It is assumed that the therapist will know the basics of spine and extremity evaluation in order to monitor the patient for symptoms that require prompt reevaluation, along with addressing relevant contributing factors in other body regions that have a significant impact on the lumbar spine.

Preoperative and Planning Phase

Before an individual elects to undergo lumbar spinal fusion, it is generally assumed that conservative measures have not had a significant impact on the patient’s condition and that they have gone through an extensive therapy program. Hopefully the individual has been taught stabilization-based exercises and has begun to address other relevant physical and cognitive dysfunctions. Once surgery is deemed necessary by the patient and rehabilitation team, preoperative management may be very useful in determining functionally relevant outcomes along with realistic goals.21 This is also the time to start on patient education regarding issues such as:

• Initial postoperative exercises

• Gait training with any necessary assistive devices

• Donning and doffing any required braces

• General overview and prognosis of the postoperative rehabilitation process

An effective preoperative program before lumbar fusion surgery should also address any other relevant patient concerns and include other advice from the members from other disciplines included in the rehabilitation team. A tour of the facility and operating room along with meeting with individuals who have already undergone such a procedure may also help to decrease patient anxiety surrounding the surgery and hospital experience.21 For the rehabilitation specialists, an understanding of the specific procedure performed is essential for safe rehabilitation. Before beginning a rehabilitation program, the therapist must know whether the patient has had a fusion with or without instrumentation. Patients who were operated on with instrumentation can generally be progressed more aggressively in the first phase of rehabilitation. Patients who were operated on without instrumentation require more time for the bony fusion to take place. Generally a callus should form within 6 to 8 weeks; the surgeon monitors this by radiograph and usually does not refer to outpatient therapy before a callus has formed. The therapist also must know the surgical approach and the levels fused. After a motion segment is fused, increased stress is placed on the levels above and below the fusion. This creates risk for acceleration of the degenerative cascade at the adjacent levels. Obviously the more levels that have been fused, the greater the stress placed on the remaining segments. When the fusion includes the L5-S1 motion segment, abnormal forces are then translated to the sacroiliac joints. To minimize these forces, the therapist must be sure that normal motion exists at all remaining segments, including the thoracic spine, shoulders, and lower extremities (LEs).

During a posterior fusion, the multifidi are retracted from the spine. This partially tears the dorsal divisions of the spinal nerves, resulting in partial denervation of the multifidi.5,22 If an anterior fusion also has been performed, then a midline skin incision will be apparent and the abdominal muscular incision is lateral. The incision passes through the obliques, also partially denervating them. For this reason the therapist should teach the patient the proper way to recruit the transverse abdominis (TA), multifidi, and pelvic floor muscles and watch for any substitution patterns to promote proper spinal stabilization.

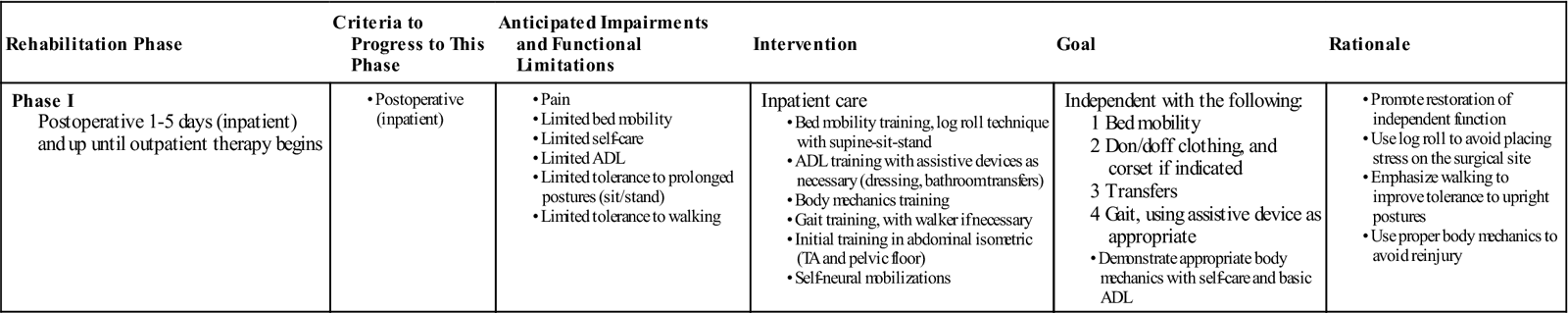

Phase I

TIME: 1 to 5 days after surgery (inpatient) and up to 6 weeks

GOALS: Patient education about daily movements, abdominal stabilization, neural mobilization, and home care principles (Table 16-2)

TABLE 16-2

< ?comst?>

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

Inpatient Phase

Most patients remain in the hospital for several days after fusion surgery. Physical therapy management during this phase consists of teaching patients the proper way to get in and out of bed, dress and perform other self-care activities, and walk (perhaps with a walker for the first 1 or 2 days). Strenuous abdominal stabilization exercises are not recommended at this time; however, attempts should be made to perform light TA and pelvic floor contractions to begin to practice them in different positions. The patient may use a large “sigh” or more forceful exhalation such as “blowing out a candle” to start to facilitate other abdominal muscles that assist with bracing. The therapist also can teach basic and simple neural mobilization for the nerves involving the lumbosacral plexus. Because of the sensitivity of the nervous system, more focus should be on activities such as “sliders” versus “tensioners.” These are described well by Bulter.12 Patients and their family should leave the hospital with an understanding of the home care required until they begin their outpatient physical therapy, especially in the absence of home PT during the interim. If the physician requests bracing of any kind, then the patient should understand the way to get in and out of the brace and when to wear it. ![]() Patients will be given instructions from the physician to avoid driving, prolonged sitting, lifting, bending, and twisting. These, along with any other specific precautions, should be understood by the patient. The PT should reinforce this information and teach patients the proper way to avoid these activities by hip hinging or pivoting. This information should be provided in written and visual form, because many patients may be medicated or overwhelmed by the recent surgery and therefore have difficulty recalling or applying what they have just been taught. Most patients are referred for physical therapy anywhere between 4 to 7 weeks after their discharge from the hospital.

Patients will be given instructions from the physician to avoid driving, prolonged sitting, lifting, bending, and twisting. These, along with any other specific precautions, should be understood by the patient. The PT should reinforce this information and teach patients the proper way to avoid these activities by hip hinging or pivoting. This information should be provided in written and visual form, because many patients may be medicated or overwhelmed by the recent surgery and therefore have difficulty recalling or applying what they have just been taught. Most patients are referred for physical therapy anywhere between 4 to 7 weeks after their discharge from the hospital.

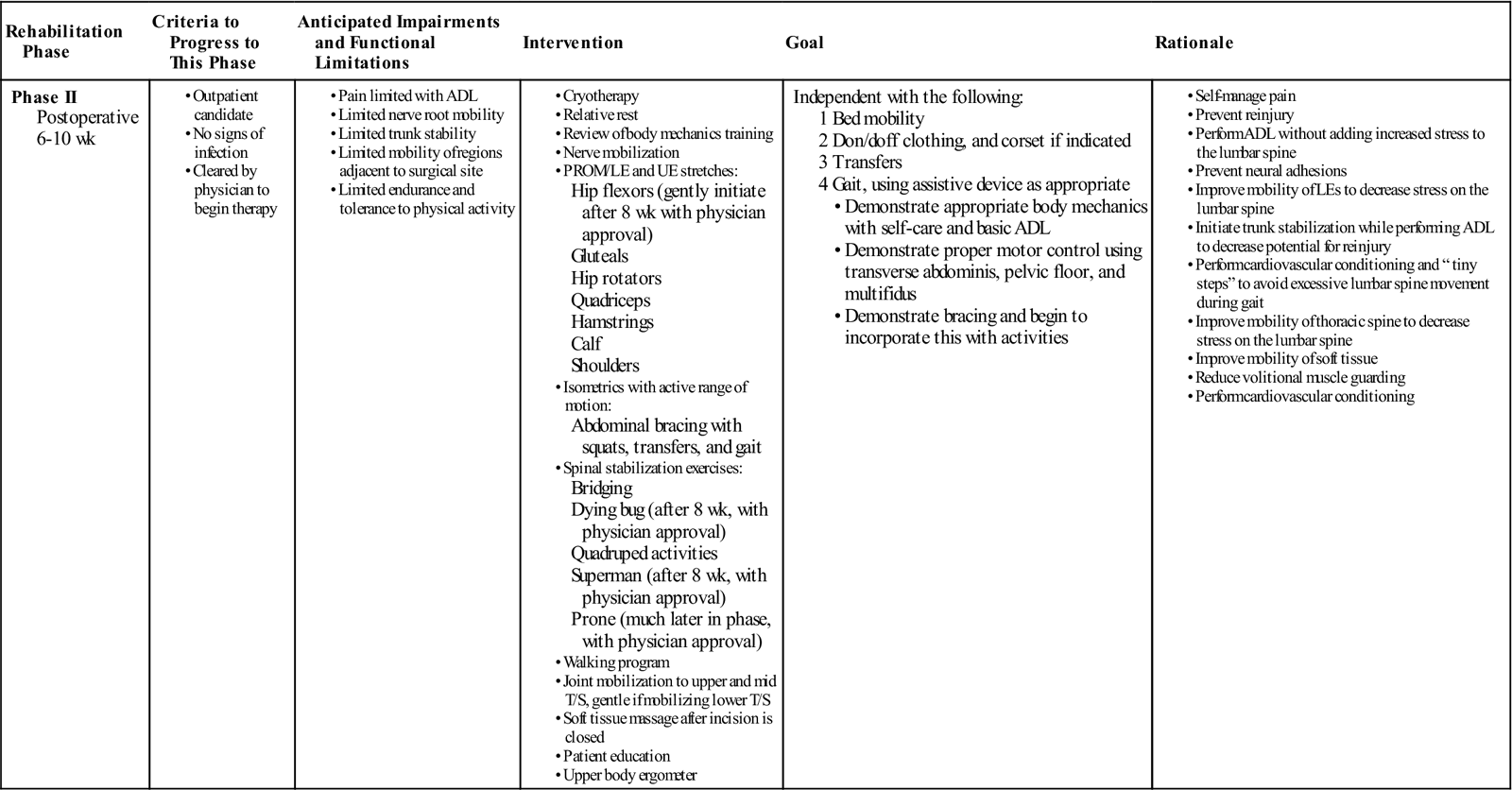

Phase II

TIME: 6 to 10 weeks after surgery

GOALS: Increased activity, tissue remodeling, stabilization, and reconditioning (Table 16-3)

TABLE 16-3

< ?comst?>

| Rehabilitation Phase | Criteria to Progress to This Phase | Anticipated Impairments and Functional Limitations | Intervention | Goal | Rationale |

|

Phase II

Postoperative 6-10 wk |

Independent with the following:

|

|

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

During phase II, patients gradually increase their activity level. While taking soft tissue healing into account, the PT can safely begin to influence the direction of tissue modeling through carefully applied stress. Patients should begin to approximate normal activities while the therapist controls the intensity of movement and exercise.

Patients progressing to the latter portion of phase II increase the intensity of the stabilization program begun in the earlier stages of the phase. They may increase repetitions and level of difficulty. Also toward the end of this phase, patients should be slowly working up to 30 minutes of exercise and physical activity at least 5 days a week as recommended by the American College of Sports Medicine.23 They can begin a light weight-training program, avoiding exercises that inappropriately load the lumbar spine but making sure to include some exercise for the lumbar paraspinals and other muscles that attach to the thoracodorsal fascia. Patients should no longer require assistance with most daily activities.

![]() Common restrictions are no lifting greater than 10 lb and no overhead lifting. Examples of exercises for this phase are listed in the following sections.

Common restrictions are no lifting greater than 10 lb and no overhead lifting. Examples of exercises for this phase are listed in the following sections.

Evaluation

Before initiating treatment the therapist should perform a thorough examination to assess the patient’s status and help to create an individualized program. The examination should include relevant tests and measures, such as posture, gait, range of motion (ROM), strength, balance, body mechanics, and specific functional tasks while making sure not to overload the lumbar spine. The therapist and patient can then begin to collaborate on and establish goals for treatment.

![]() This evaluation should include ROM for the LEs and upper extremities (UEs) but not for the lumbar spine. A complete neurologic examination should be performed to establish a baseline and should include neural tension testing.

This evaluation should include ROM for the LEs and upper extremities (UEs) but not for the lumbar spine. A complete neurologic examination should be performed to establish a baseline and should include neural tension testing.

![]() The therapist can perform strength testing for the LEs with the exception of testing hip flexor strength. He or she also can check the patient’s ability to stabilize or brace the lumbar spine isometrically, which is a test of the patient’s ability to recruit the core trunk muscles to control the spine. Core strength testing may be performed in a variety of ways; however, Lee24 describes a functional approach based on grouping core musculature into “slings.” The patient’s spontaneous body mechanics and the way the patient responds to the challenge of daily activities should be assessed. The goals of phase II are as follows:

The therapist can perform strength testing for the LEs with the exception of testing hip flexor strength. He or she also can check the patient’s ability to stabilize or brace the lumbar spine isometrically, which is a test of the patient’s ability to recruit the core trunk muscles to control the spine. Core strength testing may be performed in a variety of ways; however, Lee24 describes a functional approach based on grouping core musculature into “slings.” The patient’s spontaneous body mechanics and the way the patient responds to the challenge of daily activities should be assessed. The goals of phase II are as follows:

• Demonstrate good body mechanics for activities of daily living (ADL)

• Protect the surgical site from infection and mechanical stress

• Maintain nerve root mobility at the involved levels

• Control pain and inflammation

• Minimize patient fear and apprehension

• Begin a stabilization and reconditioning program

• Improve scar and surrounding soft tissue mobility

• Treat restrictions of thoracic, UEs, and LEs that can lead to more strain on the lumbar spine

• Education to minimize sitting time and maximize walking time

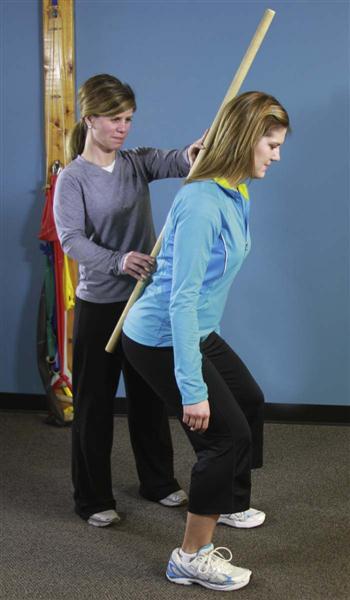

Body Mechanics Training

If body mechanics training was provided preoperatively, then it should be reviewed after surgery. If body mechanics training is new to the patient, then the therapist should go through the entire program, which is as follows:

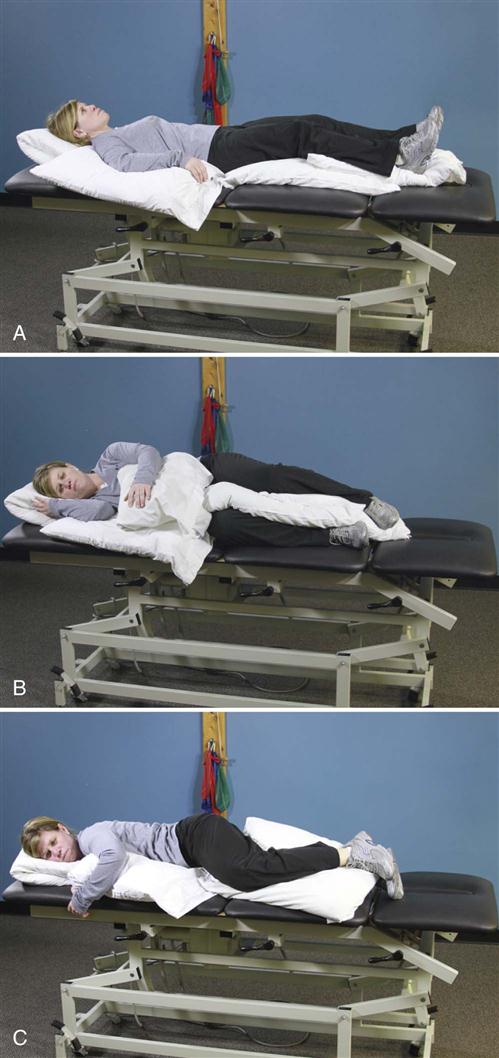

• In and out of bed (Fig. 16-4)

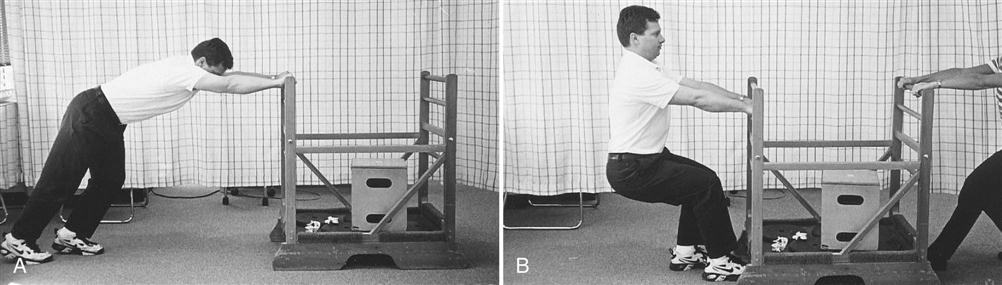

• In and out of a chair (Fig. 16-5)

• Up and down from the floor (Fig. 16-6)

• Standing

• Dressing

• Reaching

Patients must perform these activities to get dressed, use the bathroom, travel to physician’s appointments, and shop for and prepare meals. A patient who can do these activities without stressing the surgical site will heal faster and with less discomfort. Patients can accomplish all these tasks without lumbar motion if they move their hips rather than the spine.

![]() Instead of flexing the lumbar spine, they can “hip hinge” (see Fig. 16-9). Rather than twist in the lumbar spine, they can pivot on another body part (e.g., knees, elbows, hips). When teaching a hip hinge, the PT should point out that the hips should move back rather than down. After surgery, patients tend to guard and move cautiously. Showing them the way to use their momentum safely in many maneuvers makes the postoperative transition easier. For example, getting out of bed requires less bracing if the legs are moved quickly to the floor, transferring the momentum to the torso (see Fig. 16-4).

Instead of flexing the lumbar spine, they can “hip hinge” (see Fig. 16-9). Rather than twist in the lumbar spine, they can pivot on another body part (e.g., knees, elbows, hips). When teaching a hip hinge, the PT should point out that the hips should move back rather than down. After surgery, patients tend to guard and move cautiously. Showing them the way to use their momentum safely in many maneuvers makes the postoperative transition easier. For example, getting out of bed requires less bracing if the legs are moved quickly to the floor, transferring the momentum to the torso (see Fig. 16-4).

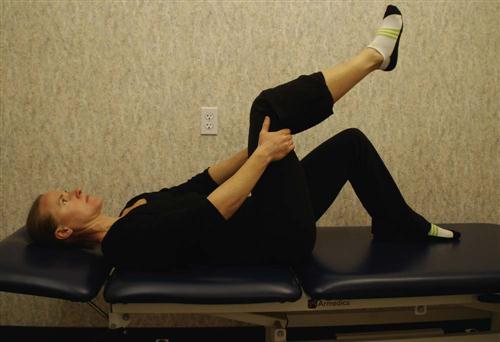

Nerve Root Gliding.

Patients should extend the knee while lying supine with the spine in a neutral position and the hip flexed to a 90° angle. When tension is encountered, the therapist helps the patient work the knee or ankle gently back and forth, gradually increasing the ROM (Fig. 16-13). This stretch may cause increased symptoms during the stretch, which should resolve immediately on relaxing. Education should be provided to the patient regarding expected and adverse reactions to neural gliding.

![]() Any lingering symptom is reason to halt the stretch until the therapist can reassess the problem. Butler12 and Shacklock25 describe an excellent approach to evaluation and treatment of neural mobility.

Any lingering symptom is reason to halt the stretch until the therapist can reassess the problem. Butler12 and Shacklock25 describe an excellent approach to evaluation and treatment of neural mobility.

Local inflammation occurs after lumbar spine surgery. Because the body forms scar tissue in response to inflammation, the nerve root can become adherent to the neural foramen or lose elasticity. It is theorized that a nerve root that is kept moving within its sheath cannot develop adhesions.12,25 Patients with nonirritable chronic leg symptoms tend to respond well to neural mobilization. However, the patient must keep the spine stabilized while moving the leg.

Decreasing Pain and Inflammation.

Patients should use medication as directed by the physician and cold packs for about 20 minutes three or four times per day to help control pain and inflammation. Patients can be taught to alternate rest periods with periods of light activity, because sustained postures can increase swelling and pain. The therapist may apply modalities in the clinic to control pain after therapy. It is very important to minimize inflammation to decrease the risk of forming scar tissue.

![]() Ultrasound should not be applied over a healing bony fusion. Patients with severe pain problems can try using a home transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) unit or interferential unit.

Ultrasound should not be applied over a healing bony fusion. Patients with severe pain problems can try using a home transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) unit or interferential unit.

Minimizing Patient Fear and Apprehension.

If patients know they can control their pain level, they may be less fearful of trying activities that may cause a pain flare-up or those that have been painful in the past. They will rely less on inactivity and medication to control pain. The therapist should spend some time initially discovering the patient’s fears and alleviating those that are groundless. Greater progress will occur in the long run if the therapist initially allays patient fears and teaches the patient ways to control pain. More recent publications have pointed toward not only to the need for additional resources addressing pain and cognition but have also suggested that group meetings with other patients undergoing rehabilitation after lumbar fusion are an integral part of the healing process.13,26

Social support is suggested to help abate pain-related fear and also allow for sharing of experiences and coping strategies. Psychosocial variables have been shown to have a large influence on disability and function in individuals with chronic back pain, so ignoring these concepts could be a large detriment to the patient’s functional improvement.11 Patients are generally very fearful after lumbar spine surgery. Excessive anxiety and worry may cause increased muscular tension along with altered movement patterns and altered pain processing. Patients are typically afraid to move, thinking they will somehow disrupt the surgery. Patients can better tolerate flare-ups and variations in their symptoms if they expect them and have been instructed in self-management of these flare-ups. Patients are generally less apprehensive if the therapist is not apprehensive. Most people recover well and should start with that expectation. If the patient appears to be developing neuropathic pain, nerve root signs, symptoms from a new level, or any other complications, then the therapist should note the symptoms calmly and convey the information to the treating surgeon for advice without conveying anxiety to the patient.

Patient Education.

Patients who are sensitive to load bearing through the spine should take frequent short unloading rests throughout the day. Those who cannot tolerate any one position for a length of time can learn to make a circuit of their activities, frequently changing tasks (avoiding prolonged sustained postures). Patients with specific position intolerance can benefit from learning ways to avoid that position while doing daily activities. Lumbar rolls are not recommended during this phase, because most patients cannot tolerate pressure on the incision site after surgery.

Patients should understand the expected postoperative course of events, particularly concerning postoperative pain. Increasing leg pain is not a good sign, even if low back pain diminishes; conversely, decreasing leg symptoms is a good sign, even if low back pain is increasing. Less leg pain is consistent with less neurologic involvement, whereas the low back is expected to be sore because of the incision and altered facet mechanics.27 Incisional pain can be expected to decrease gradually over 6 to 8 weeks. As patients begin to return to normal activities, an associated increase in muscle soreness frequently occurs. The sooner they recondition themselves, the better they will feel. Patients should be aware that their bodies will be adapting to and remodeling from the surgery for as long as 1 to 2 years. Symptoms often shift and change during that time. The therapist should teach patients to manage flare-ups using ice, rest, and resumption of previous activities within 1 or 2 days.

Stabilization, Strength, and Reconditioning.

Different approaches have been suggested to improve the active stabilization system of the lumbopelvic region, and it is beyond this chapter to compare and contrast each. However, a more thorough program would include:

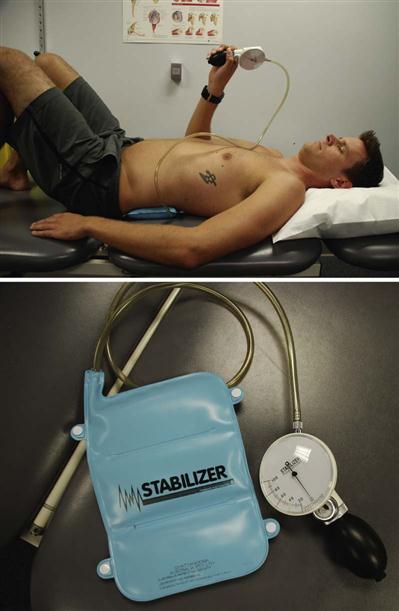

• Cocontraction of the TA, multifidus, and pelvic floor muscles with and without using pressure biofeedback (BFB) (Fig. 16-14)

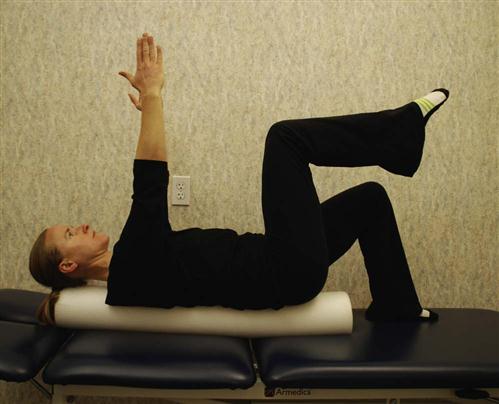

• Abdominal bracing with appropriate progression (Fig. 16-15)

Abdominal bracing and supine marching are good exercises to begin strengthening the trunk. Before bracing is initiated, it is best to make sure the patient can isometrically contract the TA, multifidi, and pelvic floor muscles.6,9,28–31 After the patient is able to do such, it is important to progress those stabilization exercises, eventually working toward functional goals that have been established. The patient should be able to contract the appropriate stabilization muscles in different postures and positions, so it is recommended that these be practiced also in sitting, standing, and quadruped. A supine progression of lower abdominal strengthening has been well outlined by Sahrmann.32

In quadruped (four-point kneeling) the patient should be able to more easily work on contracting TA while keeping other global muscles relaxed. Adding bracing along with arm and leg movements in this quadruped position is also a great way to activate the multifidus and lumbar spine paraspinals without placing the lumbar spine under undue axial load32,33 (Fig. 16-16).

It has also been hypothesized that the deep stabilizers of the spine, such as the multifidus, also have a large proprioceptive component to the active system.34 To add more proprioceptive feedback to the stabilizing system, it is integral to challenge the patient on both stable and unstable (but not unsafe) surfaces. General balance activities would also help with this type of challenge. Examples of these types of exercises may include:

• UE or LE activities while sitting on an exercise ball (Fig. 16-17)

• Supine/hooklying activities laying vertical on a foam roll (Fig. 16-18)

• Standing activities on a disc or rocker board (Fig. 16-19)

• Trunk or hip perturbations in sitting or standing (Fig. 16-20)

General strength and conditioning exercises should also be initiated during this phase of rehabilitation after it is cleared by the physician and the patient demonstrates appropriate stabilization. Examples of exercises would include:

Care should be taken when starting more vigorous strengthening activities, because it is recommended that the patient be able to use the appropriate stabilization muscles during components of the exercise before doing the full exercise. For example, before a patient performs a wall squat, they should be able to isometrically contract the inner unit and use bracing to stabilize the spine while leaning his or her back against the wall.

Maintaining Scar and Soft Tissue Mobility.

The therapist should use soft tissue techniques to maintain good scar and soft tissue mobility without disrupting the healing of these tissues (Fig. 16-21). Scar tissue tends to contract while healing. This can create a “tight” scar that restricts mobility.35 In cases of prolonged incisional pain it may be beneficial to use techniques to desensitize the tissue starting with very soft and gentle surfaces progressing to more firm and vigorous materials.

Assessment and Treatment for Restrictions of Thoracic, Shoulder, and Hip Mobility.

The following steps will help ease restrictions of the thoracic spine and hip:

• Manual therapy for thoracic motion restrictions

• LE and UE stretches for soft tissue restrictions

• Hip flexor stretches (Fig. 16-22) can be initiated in later stages with permission from the surgeon

• Quadriceps stretches (begin with prone knee flexion before progressing )

• Lumbar flexion stretch (Fig. 16-23) with surgeon approval

![]() When initiating this stretch, the therapist must not be overly aggressive, obtaining ROM at the expense of compromising the fusion site. Fig. 16-23 demonstrates an ideal ending position for this stretch, which may take several months to obtain.

When initiating this stretch, the therapist must not be overly aggressive, obtaining ROM at the expense of compromising the fusion site. Fig. 16-23 demonstrates an ideal ending position for this stretch, which may take several months to obtain.

The loss of motion caused by the spinal fusion places additional demands for motion on the adjacent segments. One of the most stressful motions in the lumbar spine is rotation, which causes a shearing effect across the disc. Since the thoracic spine is designed to allow more rotation, limited motion here may increase strain on the lumbar spine during twisting motions. The PT can use manual mobilization techniques to increase thoracic spine mobility. Many different approaches to spinal mobilization exist. One can reference Maitland,36 Mulligan,37 and Paris38 for some examples. PTs can teach patients to use two tennis balls taped together to form a fulcrum that can lie over a segment of the thoracic spine and localize motion to the segment above, thus maintaining good segmental mobility of the thoracic spine at home. This can be done in a standing or, later (when appropriate), in a semireclined position for the upper and midthoracic spine. A similar procedure can be done using a half or a full foam roll.

The hip joint is a large ball-and-socket joint with free motion in all planes. This joint can compensate for the lack of motion in the lumbar spine and should remain as flexible as possible. This can be achieved with stretching of the hip musculature. ![]() Stretching throughout phase II should be very gentle and only pushed to the point the patient can brace to prevent lumbar motion. Because these muscles attach directly to the lumbar spine or pelvis, the patient should review the principles of stretching. To stretch a muscle, one end must be fixed by something, while the other end is pulled away from the fixed end.

Stretching throughout phase II should be very gentle and only pushed to the point the patient can brace to prevent lumbar motion. Because these muscles attach directly to the lumbar spine or pelvis, the patient should review the principles of stretching. To stretch a muscle, one end must be fixed by something, while the other end is pulled away from the fixed end. ![]() If patients are not stabilizing the spine while stretching the hips, then they will invariably pull on the lumbar spine, jeopardizing the fusion. This may also occur at the shoulder complex. If inadequate shoulder flexion/elevation exists when a patient attempts to reach overhead, they may compensate with increased lumbar spine extension. Stretches to address glenohumeral ROM or latissimus dorsi (lats) tightness should also be included if needed. All stretching should involve stabilizing one area while pulling against it with another. For example when stretching the lats the patient should perform somewhat of a posterior pelvic tilt to avoid excessive extension of the lumbar spine (see Fig. 16-26). Iliopsoas stretching is initiated in a later phase with the permission of the physician. The aggressiveness of any hip stretching is dictated by the patient’s ability to control the spine while stretching.

If patients are not stabilizing the spine while stretching the hips, then they will invariably pull on the lumbar spine, jeopardizing the fusion. This may also occur at the shoulder complex. If inadequate shoulder flexion/elevation exists when a patient attempts to reach overhead, they may compensate with increased lumbar spine extension. Stretches to address glenohumeral ROM or latissimus dorsi (lats) tightness should also be included if needed. All stretching should involve stabilizing one area while pulling against it with another. For example when stretching the lats the patient should perform somewhat of a posterior pelvic tilt to avoid excessive extension of the lumbar spine (see Fig. 16-26). Iliopsoas stretching is initiated in a later phase with the permission of the physician. The aggressiveness of any hip stretching is dictated by the patient’s ability to control the spine while stretching.

![]() In addition, stretches that pull on the lumbar spine or healing soft tissues should be avoided until adequate healing has occurred. Therefore permission should be obtained from the surgeon.

In addition, stretches that pull on the lumbar spine or healing soft tissues should be avoided until adequate healing has occurred. Therefore permission should be obtained from the surgeon.

Examples of other exercises (performed while bracing) initiated in the later stages of phase II include the following:

• Bridging

• Superman (avoiding lumbar extension)

• Lateral pulls (light resistance with approval of surgeon) (Fig. 16-27)

• Seated upright rowing machine

• Scapular depression (avoid resisting more than 40% of body weight)

A callus is forming at this stage, and patients are expected to tolerate slowly increasing their activity level and returning to normal activities. What the therapist is attempting to develop at this stage is not so much muscle power as kinesthetic sense for the muscles and their role in protecting the spine. Therefore the proper form of each exercise should be emphasized.

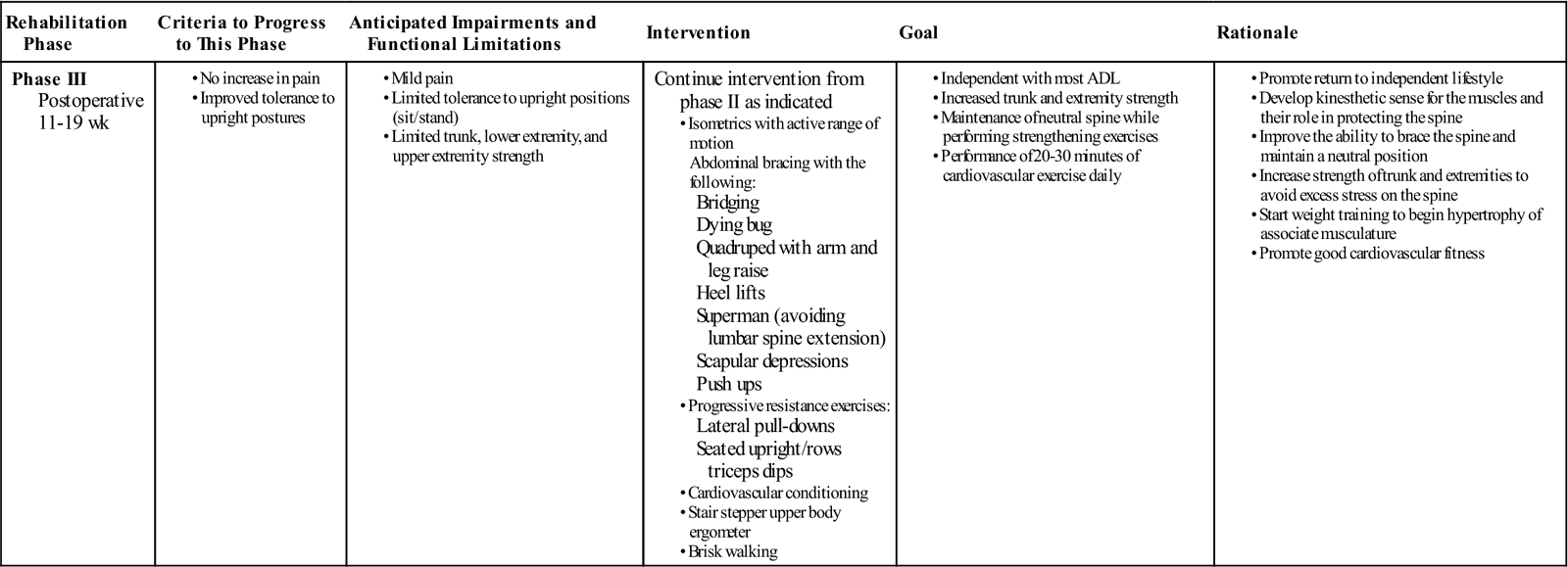

Phase III

TIME: 11 to 19 weeks after surgery

GOALS: Return to work, continue to advance/progress exercise program, practice specific skills program, initiate resistance training program (Table 16-4)

TABLE 16-4

< ?comst?>

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

During this phase, patients may start to return to work, especially if they have sedentary jobs or occupations that do not require vigorous activity. They often return to work with modified duties or on a part-time schedule. At this time they should be independent with self-care duties and also with a moderately challenging home exercise program. The use of proper mechanics should be becoming a habit but will need to be continually reinforced during specific activities. Exercises that address functional movement may be a great time to reinforce those principles. More strenuous stabilization activities, such as half and full front and side planks could be added.

![]() Patients should still avoid strenuous lumbar rotation, flexion, or extension. The early development of these muscles in their role as spinal stabilizers rather than spinal movers is a crucial component of this phase. The previous trunk stabilization activities should be progressed within the patient tolerance by modifying, for example, the number of repetitions, adding Thera-Band resistance, or performing the exercise on a more challenging surface.

Patients should still avoid strenuous lumbar rotation, flexion, or extension. The early development of these muscles in their role as spinal stabilizers rather than spinal movers is a crucial component of this phase. The previous trunk stabilization activities should be progressed within the patient tolerance by modifying, for example, the number of repetitions, adding Thera-Band resistance, or performing the exercise on a more challenging surface.

As long as the patient is able to perform the previous stabilization exercises, they may begin a light resistance exercise program. It is not advised to do complex weight lifting tasks, but to focus on light free weight activity and machine-based exercises that allow the patient to perform them with proper posture, technique, and bracing. Patients with a poor tolerance for any one position may do better on a circuit-training program.

![]() Patients should be extremely careful with overhead lifting because of the axial load and compressive forces placed on the spine. Endurance and cardiovascular exercises should also be progressed at this stage and start to progress gradually. For some individuals it may be advised to do more cardiovascular or resisted exercises in an aquatic rehabilitation environment. The buoyancy of the water may help to unload the spine but allow the patient to do partial weight-bearing exercises along with core and resisted extremity activity.

Patients should be extremely careful with overhead lifting because of the axial load and compressive forces placed on the spine. Endurance and cardiovascular exercises should also be progressed at this stage and start to progress gradually. For some individuals it may be advised to do more cardiovascular or resisted exercises in an aquatic rehabilitation environment. The buoyancy of the water may help to unload the spine but allow the patient to do partial weight-bearing exercises along with core and resisted extremity activity.

At this stage the expectation is that pain continues to decrease and be at a minimal level. Those patients that continue to have an unexpected degree of pain may need to be reassessed by the PT or by the surgeon. In the absence of any physical explanation of the pain, the rehabilitation team needs to reinforce the functional improvements and minimize the importance of pain as a marker of improvement.

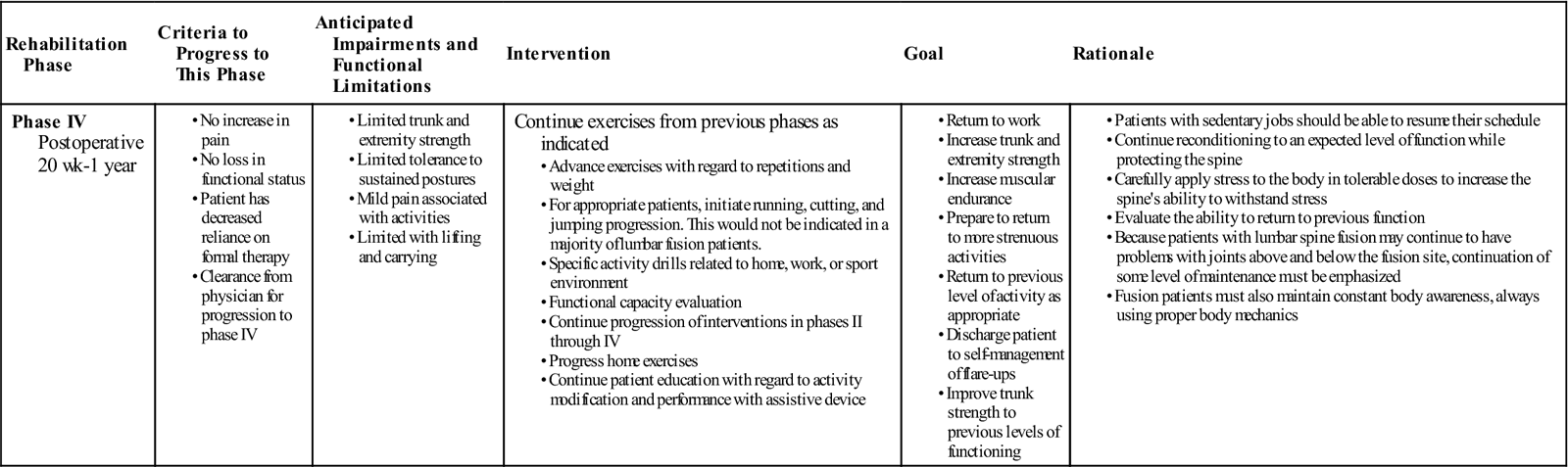

Phase IV

TIME: 20 weeks to 1 year after surgery

GOALS: Restore preinjury status, continue home program of conditioning and stabilization (Table 16-5)

TABLE 16-5

< ?comst?>

< ?comen?>< ?comst1?>

< ?comst1?>

< ?comen1?>

During phase IV the body finishes remodeling and adapting to the changes induced during and after surgery. Patients should be progressing to full restoration of their preinjury level of function and be independent with conducting their previous home and gym program. They should have a good grasp of not only the exercises and physical activity required to reach their goals but also ways to modify those activities, because at this stage it might be expected that the patient may be finishing with outpatient therapy. Proper body mechanics should be consistently demonstrated during functional tasks and patients’ understanding of these mechanics should allow them to maintain minimal strain on their back during novel situations. They should also have a good understanding of pain mechanisms, tactics to manage flare-ups, and time to contact the physician or therapist.

The bone continues to remodel and adapt to the fusion for as long as 1 year. Patients with fusions frequently develop problems at the level above or below the fusion. For these reasons, the patient should learn that spinal care is now a lifetime habit and must be maintained with regular exercise and good mechanics during all daily activities (not just those the patient perceives as stressful). It is important to consider patient motivation at this time to help design a program that will have the most realistic chance of consistent follow-through.

Patients returning to a more strenuous job or sports are now developing the extra degree of strength and skill to do so. Later in this phase (and with clearance from the surgeon) they may begin agility and sport-specific drills, such as running, cutting, and jumping. If a more comprehensive weight training program is called for it should be again geared to the specific activity faced by the patient. The program may require a greater focus on power, endurance, or skill, depending on the activity. Patients should work on maintaining control of a neutral spine during job- or sport-specific challenges during this phase, and the PT should obtain the clearance of the surgeon to begin working on these higher-level activities. The patient must demonstrate good trunk strength and control and good LE strength and flexibility before initiating agility drills. At this time it may also be necessary to perform a functional capacity evaluation and develop a work hardening program before returning the patient to full duty.

Although all therapists would like to relieve pain, some suffering is beyond the ability of current medical science to alleviate. This is a difficult concept for some patients to understand, and they may not be willing to accept it. Focus should again be on improving function and less on pain abatement. Cognitive-behavioral interventions can continue to help with pain-related fear, social adjustments, and coping strategies that may still be difficult for patients during these later stages. Therapists should make every effort to help patients accept this reality and learn to care for themselves without seeking constant medical intervention. Most people can manage chronic pain and maintain a high functional level despite the pain.

Clinical Case Review

1Tom is 50 years old. He had a lumbar fusion at L4-L5 and L5-S1, 3 weeks ago. He is now in therapy. The PT gives Tom an exercise to facilitate nerve root gliding. The patient asks, “What is the significance of this exercise?” What should the therapist tell the patient?

Local inflammation occurs after lumbar spine surgery, and the body forms scar tissue in response to inflammation. It is possible for the nerve root to become restricted by surrounding scar tissue as it exits through an opening called the intervertebral foramen. Because of the inflammatory process, the nerve also can lose elasticity. By doing activities that move the nerve within its “neural container” (sheath), it may help to prevent or free-up adhesions, which can cause pain, numbness, tingling, and other symptoms.

2The surgeon approaches the PT with some concern because the patient told the staff that the therapist was having them do “abdominal exercises” and was worried about such aggressive techniques early in the recovery period. What should the therapist tell the patient and the surgeon?

The “abdominal exercises” that the patient had been taught were not the aggressive style core exercises that might resemble gym activities. Much later in the patient’s rehabilitation, they may need to perform such exercises; however, early intervention is focused on just teaching the patient how to isometrically contract the TA, which helps to stabilize the spine in a corsetlike fashion. Because these muscles do not cause the lumbar spine to flex or extend, no shearing or abnormal forces should be placed on the surgical site. In fact, being able to control (contract) these muscles should actually help to prevent those unwanted forces.

3After being discharged from the hospital, Bill, who is 58 years old, is concerned that he is not starting outpatient therapy for another 5 to 6 weeks. He is wondering what he should do until that period. What should the therapist tell him?

After being discharged from the hospital, the physician or case manager might suggest home therapy to make sure the patient is safe and can manage the home environment without problems. In the absence of home PT, the patient should understand their precautions, which usually include avoiding bending, lifting, twisting, driving, and prolonged sitting, and know strategies to minimize strain on the lumbar spine. They should also understand all of the concepts taught in the inpatient setting, which should include bed mobility, ergonomics, body mechanics, and gait training that will help them with their ADL. During these first weeks at home, it may also be a good time to meet with others who have had the same surgery. Exercises are not recommended at this stage, but the patient should understand how to perform abdominal bracing along with a cocontraction of the TA and pelvic floor muscles.

4Lindsey is 38 years old. She had a lumbar fusion at L4-L5 about 7 weeks ago. She tells her PT that her back pain has been increasing over the past 7 to 10 days. Lindsey has complied with all instructions and restrictions. The PT reviews her chart and exercise program. Over the past 2 weeks, Lindsey has begun doing squats and using the treadmill along with the UBE for cardiovascular exercise. She has been stretching her hamstrings, hip flexors, quadriceps, and calf muscles. She also has been doing trunk stabilization exercises in the prone, supine, and quadruped positions. Lindsey also has been strengthening her upper body with bicep curls, seated military presses, and push-ups. Which of these exercises may be aggravating her condition and why?

It is most likely that the hip flexor stretches are aggravating her condition and should not be initiated until later, when sufficient healing has occurred. The iliopsoas originates at the anterior surfaces of the T12-L5 vertebra and intervertebral discs, so a forceful contraction or stretching may cause an unwanted anterior pull on those segments. In addition, exercises such as the military press that load the lumbar spine should be avoided. Finally, all exercises should be executed correctly, with proper mechanics and abdominal bracing.

5Jerry is 60 years old. He routinely used swimming as his form of aerobic exercise and is anxious to get back into the pool again. He just started outpatient physical therapy after his surgery 6 weeks ago and has asked the therapist about when he can begin an aquatic program and what exercises he could do. What should the therapist’s response be?

The buoyancy of the water could certainly be advantageous in creating an exercise program to aid in the recovery after lumbar fusion surgery. However, there are a few concerns in regards to swimming; the incision site must be healed to prevent the increased risk of infection, and the type of exercises in the pool must not place unwanted stresses on the back. It is best practice to consult the referring physician/surgeon as to when it would be appropriate to start an aquatic program and the initial exercises should be upright and not include lap swimming. Later in the program, certain strokes like butterfly and breaststroke may still be undesirable as they require increased lumbar extension to perform efficiently.

6During the initial outpatient treatment, what should be the main focus of the treatment?

Patient education should be emphasized to ensure protection of the surgery site and allow for a better recovery with less discomfort. Good body mechanics proper posture, and maintaining precautions are integral at this stage. In addition, the therapist must take care to avoid any testing that may irritate the condition. Lumbar spine ROM and strength testing of the hip flexors are some examples of testing that should be avoided.

7For the second therapy visit in a row, the patient smells of smoke and although they had originally quit to have the surgery the therapist is worried that they have started smoking again. How should the therapist handle the situation?

Without accusing the patient of smoking, the therapist might confront the patient about the smell of smoke on their clothes. It would also be a good time to remind them about the negative impact that factors such as smoking, poor nutrition, and lack of sleep have on healing, which is an integral part of the recovery from surgery. If other medical conditions such as obesity or diabetes are present, it may also be integral to assist the patient in nutritional management or direct them to other services to address these factors.

8During outpatient therapy the therapist notices that the patient is walking with a slight antalgic gait because of pain and when asked, the patient states that the leg has been a little swollen. Why might this be a concern?

With a recent onset of pain and swelling in the patient’s leg, the therapist should be concerned about the patient having thrombophlebitis or a DVT. Other signs and symptoms to look out for would be warmth and redness in the leg, especially in the calf region. In the presence of those symptoms, the patient should undergo testing as soon as possible to rule out a DVT.

9Because psychosocial factors, such as anxiety, have an influence on pain perception, how can the therapist address this to help decrease the patient’s pain levels?

Besides patient education in body mechanics and postures, the therapist needs to increase the patient’s awareness of pain expectations. The patient needs to allow 6 to 8 weeks for the incision area to decrease in pain. Increased activity levels at home or in the clinic are associated with an increase in muscle soreness, which can be expected. The therapist should reassure patients that their bodies will be adapting to and remodeling for 1 to 2 years, and symptoms often change during that time. Patients also need to know how to self-manage flare-ups and that most people recover well (they should have that expectation). Meeting with other patients who share in their experiences has also been shown to be helpful during recovery from lumbar fusion. Other professionals, such as a psychologist, may help with implementing cognitive-behavioral techniques to help reduce the patient’s pain.

10Why are stabilization exercises so important for rehabilitating these patients?

While the surgery is meant to help with the passive stabilization subsystem of the lumbar spine, both the active and neural systems are addressed through stabilization exercises. In the most common lumbar spine fusion procedure, a posterolateral fusion, the paraspinal muscles including the multifidi are stripped off the posterior elements (i.e., spinous process, lamina, transverse processes). This allows for partial tears of the dorsal division of the spinal nerves, therefore having partial denervation of the multifidi. Multifidi are the primary segmental stabilizers, and they do not spontaneously recover after low back pain or back surgery. The TA is another important muscle that may be cut during a fusion surgery. Trunk stabilization exercises are important for reeducating the multifidi muscles and the other trunk-stabilizing musculature.

11A patient asks the therapist if they should be doing back extension exercises to strengthen their lumbar spine. What should the therapist’s response be?

Initially back extension exercises should be avoided as they may cause excessive shear on the lumbar spine and place unwanted stress on the surgical site. Research has shown that performing exercises in the quadruped position, such as alternate leg or arm lifts, recruits the lumbar spine extensors sufficiently to improve trunk stability. Patients that need to get back to more strenuous activities may need to do lumbar extension activities much later in the last phase of rehabilitation and should only perform them if able to stabilize appropriately.