Chapter 161 Lumbar Microdiscectomy

Indications and Techniques

Sciatica and back pain are two of the most common reasons for referral to spine specialists today. Although the overwhelming majority of these patients will not require surgical intervention, surgery may be necessary in some patients. The lumbar discectomy is the most common surgical procedure performed in the United States today for back and leg pain,1 and the outcomes are considered excellent for patients who are good surgical candidates. Despite its widespread use, however, the lumbar microdiscectomy is not without its challenges and potential complications. Prudent patient selection, appropriate preoperative work-up, and attention to operative detail can help maximize good outcomes for this bedrock of spine surgery.

History

Sciatica has been described as far back as ancient Roman and Greek texts. In 1764, Cotugno wrote that the origin of sciatic nerve irritation was due to “acrid humors” and was the first to link symptomatology to the sciatic nerve.2 Vesalius had first identified and described the intervertebral disc in 1555, and in 1779, Pott identified the link between sciatica and deformities of the spine.3 The degenerative processes of the spine and intervertebral disc were described by Luschka in 1858, but the nature of the disc itself was unclear. Early descriptions identified the herniated disc as an “enchondroma,” which was thought to be neoplastic. The true association between the herniated disc and sciatica proved elusive until the early 20th century, when many physicians began to describe relief of sciatica with surgical interventions of the spine. In 1929, Dandy described a patient who had cauda equina due to extruded disc material resulting in nerve root impingement.4 Finally, in 1934, Mixter and Barr published their landmark paper describing their findings in 34 patients with herniated discs that were amenable to surgical intervention.5 Their treatment at that time consisted of a hemilaminectomy for decompression. While the concept was not met with universal acceptance, their work paved the way for improving surgical treatment of herniated discs over the years.6

Pathophysiology

The intervertebral disc is composed of three parts. The first is the cartilaginous end plate. These plates abut the adjacent vertebral bodies above and below and serve as a firm barrier between the disc and the surrounding vertebrae. The second component is the nucleus pulposus, a semigelatinous structure that forms the core of the disc. It serves to absorb the biomechanical strain from axial loading associated with an upright posture. The nucleus is composed of a high concentration of proteoglycans, which serve to increase the osmotic gradient between the nucleus and adjacent plasma allowing for the influx of water into the disc during recumbency. This keeps the disc hydrated and increases its ability to withstand the mechanical forces of an upright posture. To counteract this influx of water due to osmotic forces, there is an efflux of water from the disc when upright due to the mechanical compressive force of the spine. Finally, the third component of the disc is the annulus fibrosus. This collagen-laden structure surrounds the nucleus and serves to limit the lateral expansion due to compressive forces placed on the nucleus by axial loading.7,8

The intervertebral disc loses its structural integrity with time. This gradual, cumulative process is due to changes in both the biochemical and the structural composition of the disc.9 Within the nucleus itself, the concentration of proteoglycans decreases with age, resulting in a decrease in water influx and a constant efflux due to compressive forces and in a net loss of water and elasticity of the disc. Meanwhile, over the years, the annulus wears down because of the strain of mechanical forces. These two changes do not necessarily happen at the same rate. It has been proposed that herniated discs may result if there is a preferential loss of annulus, resulting in a disproportionate strain on the nucleus. Over time, the weakened annulus gives way, with extrusion of disc material.10 Interestingly, despite the fact that disc degeneration is progressive, the peak incidence of disc herniation is in the fourth decade of life (most commonly in the third through fifth decades). This is thought to be because a hydrated, expansive disc is necessary for herniation. As a person gets older, with continued disc desiccation, the nucleus is not flexible enough to extrude past the annulus. During the third to fifth decades, the situation of a hydrated, expansive disc exerting strain against a weakening annulus results in herniation.9

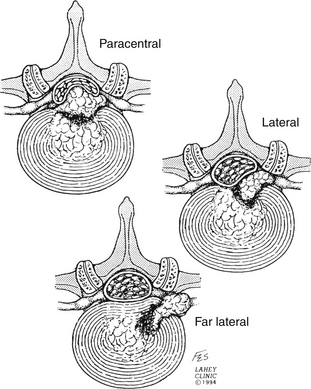

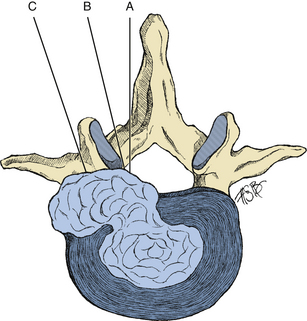

Although disc herniation can present with back pain alone, it classically presents as radiculopathy. The radicular pain seen is due to the location of the disc herniation. Herniations between the midline and neural foramen (posterolateral herniations) are by far the most common. By contrast, far lateral disc herniations comprise only about 10% to 15% of herniated discs.11 Central disc herniations also occur but are rare. They are clinically relevant, however, because of their propensity for causing cauda equina syndrome (Fig. 161-1).

The classic, posterolateral herniation12 is most common because of the anatomy of the posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL). The PLL is thickest near the midline and weakens out near the lateral margin. When a disc herniates, it extrudes through the weaker, lateral margin of the PLL. This results in pain from compression of the nerve root, and sciatica may ensue.

The pathophysiology of radicular pain is not exactly known but does require a compressive component. There is often incongruence between foraminal stenosis and clinical symptoms. As many as 20% of asymptomatic individuals will have a compressive disc herniation.13 In addition, most patients with radiculopathy due to a herniated disc will clinically improve with time despite the fact that their radiographic findings persist. The mechanism by which a compressed nerve root generates pain is incompletely understood. Proposed theories, which have all been demonstrated in animal models, include nerve edema, alterations of nutritional transport, and axonal conduction inhibition.14 Local inflammatory markers have been proposed to play a role. This is supported by the success of anti-inflammatory medications for symptomatic relief. Phospholipase A2 has been identified in surgically excised herniated discs.15

Patient Evaluation and Surgical Indications

In evaluating someone with a herniated lumbar disc, great care must be taken to accurately correlate imaging findings with clinical picture. The incidence of a herniated disc is quite high in the general population, and radiographic presence alone is not a sufficient indication for surgical intervention. Proper patient selection (and not necessarily surgical technique) is believed to be the best predictor of a good outcome.10 Radiographic findings must support the clinical decision to operate, and this cannot be compromised to justify surgical intervention.

Presentation

In most centers, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the standard imaging modality for evaluating back pain; however, modern imaging has failed to accurately correlate findings with the true cause of back pain. The common scenario is the identification of abnormalities without the known significance of these findings.16 For instance, the presence of a “dark nucleus” has been shown to predict the likelihood of back pain, and thus, patients with known pathologic imaging findings are more likely to experience poor outcome,17,18 although a dark nucleus has not been definitively related to any pathologic condition.

While mechanical back pain alone is not generally accepted as an indication for discectomy, exceptions may exist. One such exception is the disc herniation resulting in central spinal stenosis. While patients with disc herniation with central spinal stenosis most often present with claudication symptoms, they often also develop a stooped posture in an attempt to open the spinal canal. This chronically flexed positioning can result in lumbar fatigue and subsequent back pain. These patients may benefit from surgical decompression to alleviate the stenosis. With the resolution of stenosis, posture restores to a more physiologic stance and back pain may improve.19 Another scenario in which back pain alone may indicate a discectomy is the large central disc herniation with avulsion of the PLL. This has been proposed to cause tension on the PLL, which can be a significant pain generator. It has been demonstrated that surgical discectomy in these patients will relieve this tension, resulting in improved back pain.20 Although we acknowledge that exceptions exist, as a general rule, radicular symptoms, not isolated back pain, should be the deciding factor in whether to perform a lumbar discectomy.

As time progresses, back pain may yield to radicular symptoms, and, in fact, there is usually an inverse temporal relationship between the two. These symptoms may include pain, numbness, or paresthesias, which may initially be attributed to other causes, such as osteoarthritis of the hip or peripheral neuropathy. Once correctly identified as radiculopathy, the clinical observer can often (up to 70% to 80% of cases) predict the location of the pathologic disc based on clinical symptomatology alone.21–24 For instance, a standard posterolateral disc herniation should compress the root exiting from the next lower neural foramen (e.g., an L5–S1 posterolateral disc herniation will compress the S1 root) (Fig. 161-2). This is not what is expected from a far lateral disc herniation, where the herniated disc compresses the exiting root from the same level (e.g., an L5–S1 far lateral disc herniation should compress the L5 root). True radiculopathy should follow a dermatomal distribution and may by exacerbated by standing, walking, or Valsalva maneuvers. Severity of pain, on the other hand, can be quite difficult to interpret. For instance, the location of the disc has been shown to affect the severity of symptoms. Extraforaminal disc herniations have been found to be more painful, perhaps because of their direct compression of the dorsal root ganglion.25 In addition, pain tolerance varies significantly between individuals, and thus the overall effect of the pain on the patient’s quality of life is most important. Generally, in the scenario in which a patient has a true disc herniation but symptoms are inconsistent with what is expected, good outcomes cannot be expected from surgical decompression.

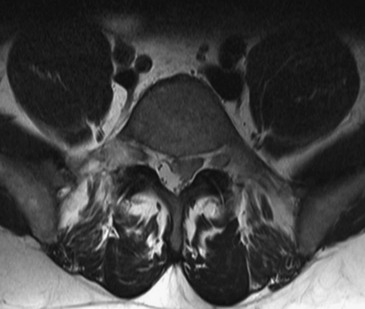

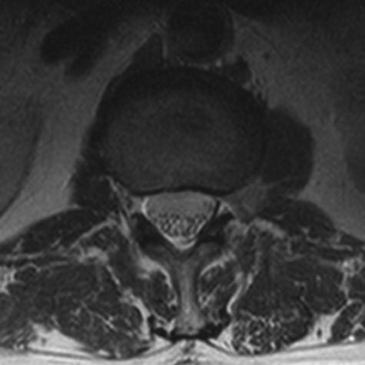

A special sequela of disc herniation is the cauda equina syndrome. The typical scenario is an acute disc herniation in the setting of pre-existing central canal stenosis (Fig. 161-3). Presentation is one of perineal numbness, loss of bowel or bladder function, and possibly leg weakness. Back pain may also be present, but it is often disproportionate to the severity of neurologic symptoms. Cauda equina syndrome is a surgical emergency and must be immediately decompressed to prevent permanent loss of function. In a case series by Shapiro,26 those patients receiving decompression within 48 hours of onset were more likely to recover from motor and bladder deficits. This is certainly not a concrete rule, and even with emergent discectomy, recovery is not universal and bowel or bladder disturbances can be life-long deficits.19,27,28 Poor prognostic factors include acute onset, bilateral radicular pain, and saddle hypesthesia.27

On clinical examination, certain findings can also help to localize the level of the herniated disc. A positive straight leg raise is a classic finding with herniated lumbar discs and is most often seen with herniation of the L4–L5 and L5–S1 discs. Compression of the axilla of the nerve root is more likely at these levels and can be elicited with this maneuver. In contrast, the femoral stretch test is more likely to be positive with herniations at higher levels.29 Motor deficit is another finding in some cases. While a useful examination finding when present, because of significant overlap in innervation, true weakness to confrontational testing may be masked from the examiner. Of all historical and examination findings, monoradiculopathic leg pain is the best clinical correlate, superior to straight leg raise and the presence of sensorimotor deficits.21

Imaging

With advances in medical technology and concerns over medical liability, there has been a drastic increase in the use of medical imaging over the years. More than ever, patients often present requesting or even demanding that imaging be performed. It should be remembered that the decision to undertake a lumbar discectomy should be first and foremost a clinical one. Pursuing a diagnostic test should be done only if clinical suspicion is such that the practitioner is considering surgical intervention. If the clinical history is not consistent with a pathologic condition requiring surgery, then the decision to obtain imaging should be questioned. It is important to note that the radiographic size of a herniated disc does not correlate with symptom severity. Those patients with congenitally narrow foramina should experience earlier symptoms than those without. In addition, as stated above, variations in pain tolerance can also contribute to inconsistency.

Timing

Multiple studies have examined the natural history of herniated discs to determine the appropriate timing of intervention. Most data support pursuing conservative therapies for at least 4 weeks initially before offering surgery for radicular pain, even in patients in whom the clinical and radiographic data support a good surgical outcome. This is because, although quicker relief has been demonstrated with surgery,30 the long-term outcomes are similar for conservative treatment and surgery.31–34 It should also be reiterated that the rules for clinical correlation of clinical and radiographic findings should not be broken simply because conservative therapies fail. A patient who does not respond to conservative measures should not become a surgical candidate unless he or she has a correlating disc on MRI. If the imaging does not support the clinical picture, surgery is not a viable option.

Although the data suggest that long-term outcomes are similar for surgery and nonoperative management for radicular pain, in reality, at least in our practice, selected patients who are surgical candidates may be offered surgical discectomy before completion of a full course of conservative therapies for one of two reasons. The first is that patients are often not interested in pursuing conservative therapies and would rather proceed with urgent decompression because they cannot tolerate the pain. The second is the widely held belief that longer duration of symptoms before decompression will result in longer time until postoperative resolution. There is concern that permanent deafferentation can occur from prolonged compression.24,35 Histopathologic specimens have shown changes within the nerve root with prolonged compression that may result in irreversible damage.20,31,35 Although the exact timing is unknown, it is thought that this process takes at least 3 to 6 months to occur. The counterargument is that spontaneous disc resorption does occur and has been documented. While counterintuitive, this seems to be more likely with larger extruded discs than with smaller contained discs. Disc herniation recruits inflammatory cells and subsequent phagocytosis of extruded disc material.31,36–39

Another factor that may play a role in the decision of surgical timing is the issue of financial concern. While some argue that surgery is more costly, others contend that the cost of conservative therapies is higher because of the longer duration of treatment and the potentially longer period during which the patient may be out of work. Patients often wish to pursue early surgery to return to work more quickly. Indeed, studies have demonstrated that increased time off of work before surgery is associated with a poorer outcome.40 Although the cost of surgery can be high, the long-term cost of continued conservative therapies may actually prove more expensive than surgery in select cases.41

Although the patient with a herniated disc most often presents with radicular pain, those patients with motor weakness at presentation should be approached differently. It is generally believed that a motor deficit due to nerve root compression is a more urgent issue than pain alone. Few would argue against the claim that a severe, acute deficit is a clear-cut surgical indication. In addition, a stable deficit that has been managed conservatively but fails to improve is also a surgical indication.20,35,42 Patients who present with a minor, stable deficit represent a more ambiguous situation. It has been our experience that these patients can be treated and followed conservatively. Typically, the acute disc herniation will manifest with an acute deficit that is stable or improves with time. A progressive deficit, on the other hand, should raise suspicion of another pathologic condition. It is often observed that motor deficits improve along with pain over time. If radicular pain is improving, it may be prudent to monitor a mild focal deficit in anticipation that it will subside with time. Surgery for severe deficit with concordant radiculopathy, in contrast, should not be delayed, although patients may not recover completely even with urgent surgical intervention.

Preparation

Principles

Once the decision has been made to perform a surgical decompression for a herniated disc, certain principles should be followed. For instance, the goal of surgery is nerve root decompression, not necessarily to perform an aggressive discectomy. In those patients with foraminal stenosis due to facet arthropathy and a disc bulge, a laminoforaminotomy may be a better option than to open the annulus unnecessarily. The presence of a herniated disc does not mean a discectomy is necessary. In carrying out the decompression, the surgeon should do everything possible to minimize tissue trauma and bone removal. Reduced tissue trauma results in less postoperative scar formation. Overly aggressive bony decompression can lead to pars interarticularis fractures and future instability.

In the operating room, standard surgical steps must be used to prevent wrong patient, level, or side surgery. Treatment with preoperative antibiotics is the standard of care as these have clearly been demonstrated to reduce postoperative infections.43 The use of elastic stockings and compressive boots on patients is recommended to reduce venous thromboembolism, although these have not been proven definitively to be beneficial. A urinary catheter is generally not necessary because of the expected short operative time.

The decision to use microscopic visualization is made according to the surgeon’s preference. Loupe magnification with a headlight and the operating microscope are both good options, and results are equal with either.20 Use of the operating microscope is preferred at our institution because it offers the benefit of ideal visualization for both surgeon and first assistant. It does have the drawbacks of increased cost, lower availability, and unwieldiness when the surgeon is not familiar with its use. Regardless of which device is used, microscopic technique should be employed, as it has been shown to improve accuracy while reducing pain, tissue trauma, blood loss, and hospital stay. That being said, long-term patient satisfaction is no different between standard open discectomy and microdiscectomy.44,45

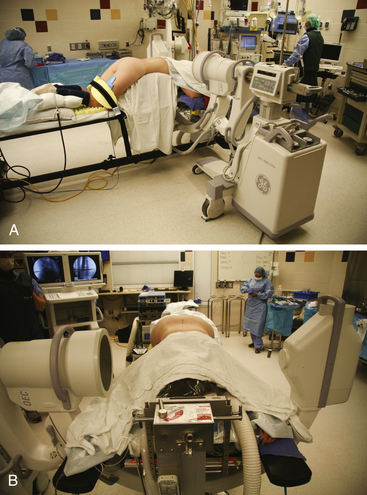

Positioning

While each of these positions has its indications and advantages, the most widely used is the prone position (Fig. 161-4). The patient is placed on a Wilson frame, a Kambin frame, or gel rolls, with the surgical region centered at the apex of the frame. Pressure on the abdomen should be minimized to reduce airway pressures, epidural venous congestion, and intrathecal pressure. The patient’s arms should be placed on arm boards slightly abducted and extended in a cephalad direction in the “Superman” position. By having the arms in a cephalad direction as opposed to down along the patient’s side, the surgeon is afforded more working room against the patient. This also provides more room for x-ray or fluoroscopy when the time comes to obtain a localizing film. Shoulder extension and abduction should be kept less than 90 degrees to avoid brachial plexus injury at the thoracic outlet. All pressure points should be liberally padded to prevent pressure-related ischemia. Ocular compression from spine surgery, especially in conjunction with hypotension can result in blindness.46 The ulnar nerve can be protected by padding the medial condyle of the elbow. Palpation of peripheral pulses is recommended to evaluate for vascular compression.

An alternative to placing the patient prone on a frame or gel rolls is the knee-chest position. The knee-chest position has been used for obese patients in whom mechanical ventilation would be impossible. This seemingly has the added advantage of reducing epidural venous engorgement and also allows for the abdominal great vessels to fall away from the spine, theoretically reducing their risk of injury.10 While theoretically beneficial in reducing abdominal and thoracic compression, the knee-chest position has not been demonstrated to have significantly different intra-abdominal and thoracic pressures than the prone position.47

A third option is the lateral decubitus position. This is another viable option for those patients whose obesity makes mechanical ventilation in the prone position an impossibility. The patient is placed symptomatic-side-up in maximal flexion with knees and shoulders curled to chest. The region of interest is centered at the operating table joint, and the table is flexed to further widen the interlaminar space. This allows for easier mechanical ventilation at the expense of comfortable working conditions. It also has the advantages of greater possible flexion and a cleaner surgical field as any bleeding runs out of the field as opposed to pooling.

Technique

Posterolateral Disc Herniation

Approximately 70% to 90% of symptomatic disc herniations are in the posterolateral location.10,48 To access these herniations, either a midline or paramedian vertical incision centered above the disc space is planned. This region is prepped in a standard, sterile fashion, and the skin is incised sharply. The decision to use local anesthetic is left to the surgeon. The dissection is then carried down through the subcutaneous tissues with monopolar cautery to the dorsal lumbar fascia. The fascia is incised with cautery on the ipsilateral side of the spinous processes, and the paraspinous musculature is dissected off of the spinous processes in a subperiosteal fashion. Care should be taken to preserve the interspinous ligaments in an attempt to minimize destabilization. By staying in the subperiosteal plane, muscular bleeding can be kept to a minimum. This technique is performed with the monopolar cautery in the surgeon’s dominant hand, and gentle traction of the muscle provided by either suction or a periosteal elevator in the other hand. The dissection is carried down to the lamina, and the muscles are further swept laterally out to the medial border of the facet joint. This lateral exposure can be continued with the cautery or can be done bluntly with a Cobb periosteal elevator. Dissection does not need to be carried out to the transverse process, although exposure of the facet joint aids in placing the retractor. The facet capsule itself must not be violated to avoid destabilizing the joint.

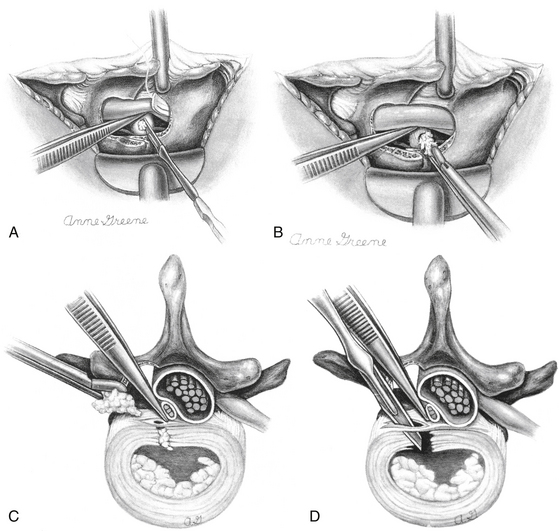

For further visualization, a deeper self-retaining retractor should now be used. Many options exist, including the Taylor, Williams, and speculum-style retractors (Fig. 161-5). The choice is not as important for visualization as attention to detail in removing all soft tissue off of the laminae. It is now recommended to take another localizing image with an instrument in the field to confirm accurate exposure. A Penfield #4 dissector placed in the interlaminar space works well. At this time, and until decompression complete, the operating microscope (or Loupe magnification) is employed.

Many techniques are available for performing the laminotomy. Accurate placement is more important than the actual method. In making sure that the decompression is centered over the disc space and is not so large as to risk fracturing the pars, the surgeon can gain a sufficient window to the herniation while minimizing tissue destruction. The initial step is to remove the inferior lip of the superior lamina with either a Kerrison punch or a high-speed burr. It is our preference to perform the laminotomy with the Kerrison punch, but the lamina may often need to be thinned out with the burr or a Leksell rongeur first because of its depth. The laminotomy should begin medially at the base of the spinous process and be directed superiorly. The upper extent should depend on the location of the disc herniation but as a general rule should be taken to the insertion of the ligamentum flavum. The decompression should then be directed laterally toward the facet joint again with either a Kerrison punch or the burr. A 0.25-inch osteotome is also a useful instrument for this maneuver. A cut is made perpendicular to the initial bone removal laterally along the lamina and then another perpendicular cut along the medial facet joint. This allows for the medial third of the inferior articulating process to be fractured off en bloc and creates a good working window to access the axilla. Most of the decompression involves the uppermost lamina (as it hangs over the disc space). The superior lip of the more inferior lamina may require removal, especially if the disc fragment is extruded in a caudal direction. It is advised to preserve the ligamentum flavum during the laminotomy to protect the thecal sac from injury. The ligament may be removed sharply with a scalpel or in a piecemeal fashion with a Kerrison punch or it may be disconnected from laminar attachments with an up-angled curette and peeled off en bloc with a pituitary rongeur. Each of these maneuvers has the inherent risk of tearing the thecal sac, which, while not of severe consequence, can be avoided if care is taken.

With the root and thecal sac mobilized, attention may now be turned to the discectomy. In ideal situations, the offending disc is a completely extruded free fragment that can be teased out carefully from the epidural space with a micropituitary rongeur. If the only pathologic condition is a truly extruded free fragment, then the prudent maneuver is to stop the decompression here with a simple “sequestrectomy.” To enter the annulus and perform a more extensive discectomy has not been proven to be beneficial and may even lead to worse long-term outcomes.49–51 In those situations in which compression is due to a retained disc within the disc space, the annulus should be opened sharply with a scalpel in a linear fashion. Once opened, gentle downward pressure on the annulus can be applied in an attempt to extrude disc material into the epidural space for removal (Fig. 161-6). A difficult decision often faced by the surgeon is how aggressive to be with the discectomy. There is no clear consensus as to the amount of disc that should be removed, and more extensive removal has not been shown to correlate with recurrence or instability.52 A more aggressive discectomy may, in fact, lead to worse long-term outcomes.53 It is the authors’ view that if the annulus must be opened, then it is prudent to remove what is easily expressed from just within the annulus without attempting to strip the endplates of disc material. For material just under the annulus that is causing a persistent bulge of the PLL, a down-facing curette or a Woodson dental tool can be inserted into the annulus to force this disc back to the annulotomy for removal.

Once the discectomy has been completed, the disc space should be thoroughly irrigated to wash out any remaining free fragments. The wound is then closed in layers with 0 Vicryl sutures in the dorsal lumbar fascia followed by 3-0 Vicryl sutures in the dermal layer. A running, subcuticular suture is used for the skin.

Central Disc Herniation

The symptomatic central disc herniation is an infrequently encountered entity. It must be distinguished from the very common central disc bulge. These disc bulges are quite often found incidentally and are generally of no clinical significance. The truly symptomatic central disc herniation only comprises about 1.2% to 10% of symptomatic disc herniations,48 but these are clinically relevant as the offending agents in cauda equina syndrome.

The surgical approach to central disc herniations is usually the same as that for the posterolateral disc herniation. The surgeon must choose the side of approach based on radiographic findings if the disc is at all eccentric to one side. If the disc is truly midline, then the approach should be performed on the more clinically symptomatic side. The acute disc herniations are soft and can usually be removed successfully from a unilateral approach. Chronic disc herniations, however, may be calcified and adherent to surrounding structures, which may preclude removal from a single-sided laminotomy. The consistency of the disc and its maneuverability is usually not known prior to exposure. Because of this, it is advised to proceed with a unilateral takedown with a laminotomy up to the underside of the spinous process. As much disc as possible is debulked from this side, and the epidural space is palpated with a blunt nerve hook or Woodson elevator. If the remaining disc cannot be successfully removed without undue tension being placed on the thecal sac and nerve roots, then a contralateral laminotomy should be performed. Postoperative cauda equina syndrome has been reported after lumbar decompression, and unnecessary nerve root retraction should be avoided.54 If a bilateral decompression is necessary, the decision must be made as to whether to perform a complete laminectomy versus bilateral laminotomies with preservation of the spinous process and interspinous ligaments. The authors believe that as much normal anatomy as possible should be spared, but above all else, aggressive nerve root manipulation during discectomy should be avoided. Regardless of the extent of bony decompression, instrumentation and fusion are unnecessary.

Extraforaminal (Far Lateral) Disc Herniation

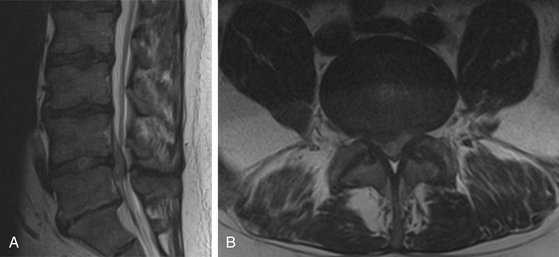

Far lateral disc herniations comprise 1% to 10% of symptomatic discs.55,56 These discs are most often found in older patients and at the L3–L4 and L4–L5 levels (Fig. 161-7).57 When examining outcome of surgical intervention, early literature suggests comparable success rates with standard disc herniations, but more recent data suggest poorer outcomes in these patients.11,20,25,58,59 While commonly referred to as a collective entity, these herniations can be found anywhere in relation to the neural foramen. Likewise, many surgical approaches have been described to access this herniation. The surgical approaches have many similarities55,60–62 and can be categorized into three basic subgroups (Fig. 161-8).

To access the disc at the medial part of the foramen, a traditional midline exposure can be used. Advantages to this approach include low blood loss with subperiosteal dissection of the paraspinous musculature. In addition, this is a view with which most surgeons are familiar and affords early visualization of the exiting nerve root. The root can be exposed via a standard hemilaminotomy and followed out the foramen laterally and freely mobilized. The underlying disc can thus be removed from within the foramen. Disadvantages include the necessity of more tissue dissection to gain such a lateral exposure and subsequent postoperative pain and narcotic use and the possibility of clinically significant facet removal.12,59,63

In a technique described by Hood,55 discs in the lateral neural foramen were targeted by a more direct approach. This entails a transforaminal approach with a lateral facetectomy.12 A paramedian incision is created 1 cm lateral to the midline, and an intramuscular approach is used to gain access to the lateral facet joint. A partial, lateral facetectomy is performed with a high-speed drill and Kerrison rongeur. From this window, both the rostral and caudal pedicles are palpated from the outside as is the dorsally displaced nerve root. The root is then mobilized to gain visualization, and the disc fragment is removed. In the event that disc material is present in both the lateral and medial foramina, the exposure can be shifted medially for a laminoforaminotomy if needed. Hood’s technique has the advantage of preserving the majority of the facet joint and limits the pain of shearing the muscles off of the spinous processes. It is also quite versatile in allowing access to the entire facet complex despite being performed through a limited incision. Disadvantages, however, include a potentially bloody exposure to work within the muscle, which can make visualization more difficult through a narrow corridor. In addition, a lack of familiarity with this technique can make it a bit difficult to locate the nerve from a lateral approach.

Possibly the most technically challenging herniations to remove are those situated outside the neural foramen. While many variations exist, the approach has been described as “far lateral,” “extraforaminal,” or “paramedian, tangential.” This avoids the need for a facetectomy altogether, which can lead to delayed instability and chronic back pain.64,65 It also involves a paramedian incision (3 cm off of the midline) with a muscle-splitting technique. Visualization can be improved with a table tilt away from the surgeon. The dorsal lumbar fascia is incised with monopolar cautery, and palpation with a finger can locate the facet joint and transverse process. The muscles are split, and a speculum-style retractor is docked at the lateral border of the facet joint. At this time, under Loupe magnification and headlight or operating microscope, the muscular attachments are freed from the transverse processes, and the intertransverse ligament is incised. The exiting nerve root is identified and mobilized for removal of the underlying disc fragment. Advantages of this approach include direct access to the herniation while potentially eliminating bone removal. There are disadvantages,59 however, which include impedance to the target site by a high-riding iliac crest. This makes the approach very difficult with L5–S1 disc herniations. Furthermore, discs that have a medial component (especially under the PLL) cannot be easily removed from this trajectory. The location of the dorsal root ganglion makes far lateral disc herniations quite painful and thus more sensitive to lateral nerve root manipulation. Difficulty in identifying the root without familiar landmarks can result in nerve injury and worsening symptoms postoperatively despite disc removal.66

Postoperative Care

Goals of the immediate postoperative period are directed toward quick recovery and return to the patient’s daily routine. Patients are usually discharged the day of surgery but may be kept overnight if necessary. Steroids, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, and cytotoxic medications should be avoided in the first 2 weeks after surgery.67 Early ambulation is encouraged, as well as low-impact activities such as swimming. Many patients who are employed in nonmanual labor jobs can return to work within the first week. Those with more strenuous jobs may require up to a month off of work because of muscle spasm with activity. There is no evidence to support the view that activity can result in recurrent herniation, and postoperative pain should guide the level of activity.

Complications

Intraoperative Complications

The most common intraoperative complication of a lumbar discectomy is a dural tear.68 If appropriately identified and addressed, however, it is usually not a clinically significant event. When feasible, the dural rent should be oversewn with a small, nonabsorbable braided suture such as a 6-0 Ethibond. Larger defects that cannot be closed primarily may require a dural graft such as fat, muscle, or a synthetic substitute. Ventral tears prove more challenging as they cannot be directly visualized or primarily closed. Whenever primary closure is not possible, the use of static agents such as fibrin glue may be necessary. Wound closure should consist of a tight, multilayer approach.

If not properly addressed, postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leaks can result in wound dehiscence, meningitis, and symptomatic pseudomeningocele.69–72 A pseudomeningocele, while often benign, has been associated with recurrent back and leg pain with herniation of nerve roots into the dural defect.70 This may warrant reoperation for exploration and repair. Postoperatively, if there is any concern as to the success of the dural repair, it is advised to keep the patient lying supine for at least 24 hours. With a persistent pseudomeningocele, a lumbar drain may be necessary along with prolonged bed rest to allow additional time for the defect to heal. Good outcomes can still be expected with prompt recognition and good closure.

A much more serious complication of the lumbar discectomy is violation of the anterior longitudinal ligament with injury to the retroperitoneal structures. This is usually done during overly aggressive discectomy with a pituitary rongeur. Unexplained egress of irrigation from the disc space should alert the surgeon to a ventral annular tear. It should be noted that the depth of the intervertebral disc averages 3 cm but can be quite varied. Depending on the level of approach, the aorta, inferior vena cava, iliac arteries and veins, abdominal viscera, or ureters may be at risk. The incidence of vascular or bowel injury is anywhere from 1.6 to 17 in 10,000 cases. In spite of best treatment, the mortality rate after these injuries is near 50%, and in these cases death is often due to delayed diagnosis. If the injury is unrecognized, mortality rates approach 100%.73 A high index of suspicion should lead to the diagnosis in the patient with abdominal pain, flank pain, hypotension, fever, or severe ileus. Abdominal x-rays, CT, angiography, intravenous pyelogram, or ultrasound may all be used in diagnosis.

Injury to a great vessel may present with brisk bleeding from the working site. Unfortunately, in approximately half of the cases this may be absent.74,75 Unexplained signs of hypovolemia, including hypotension and tachycardia, should raise suspicion of a vascular injury, and prompt recognition is important. If the patient is hypotensive and the clinical picture is suggestive of a significant injury, the wound should be packed and the patient immediately flipped to the supine position in preparation for repair by a general or vascular surgeon. A midline laparotomy may be performed and the surgeon can hold pressure on the aorta until assistance arrives. If brisk bleeding is encountered but the patient is clinically doing well, urgent angiography may be advisable to localize the injury prior to laparotomy. Young patients with a healthy cardiovascular system may compensate for quite some time prior to clinical deterioration. Not all vascular injuries present acutely. If both an artery and vein are involved, an arteriovenous fistula may form in a delayed fashion.76,77

Postoperative Complications

The presence of persistent symptoms is the most common “complication” of lumbar disc surgery.78 The expected outcome from surgery is the immediate relief of the patient’s radiculopathy. The persistence of radicular pain postoperatively should raise concerns of residual disc fragment or wrong-level surgery. In either scenario, reoperation is necessary.

The recurrence of symptoms after time suggests either recurrent herniation or scar formation. The presentation is similar in either case, and the reoperation rate for recurrent radiculopathy is 5% to 20%.79–81 An MRI with gadolinium enhancement can provide insight into the nature of the pain. Scar tissue is expected to enhance avidly whereas recurrent disc herniation does not. Recurrent disc herniations can even occur at the same or different level. Symptoms tend to recur an average of 8 years postoperatively, and many occur within the first year.82

If the decision is made to perform a reoperation for a recurrent disc, the second surgery will be more challenging than the first because of scarring and obscure tissue planes. As a result, risks are higher with a second surgery and may include dural tears and nerve root injury. Upon exposure, a curette should be used to identify the laminar edges and identify a plane between scar and the dura. The laminotomy should be widened to identify the normal epidural space. The exposure should then be taken back to the previous site for mobilization of the root and disc removal. A repeat surgery generally does not require fusion except if the motion segment is clinically unstable. Fortunately, the rate of success is similar to initial operations.83,84 Multiple recurrences, however, increase the likelihood of the need for fusion and worse outcomes.80,85

Postoperative “failure” of the microdiscectomy has often been attributed to scar formation around the nerve root. This scar formation can tether the nerve root, causing compression, irritation, and ischemia with persistent pain, reoperation, and overall poorer long-term outcomes. A correlation has been found between extent of scarring and recurrent symptoms; however, even with the most extensive scar formation, pain was present less than 20% of the time.86 Scarring can also distort normal anatomy, resulting in reherniation in atypical locations, such as intradural or intraradicular.87,88 Clinical presentation of reherniation in the presence of scar-induced tethering may be polyradicular in nature.89 Soft tissue trauma, perineural blood, and gelatin sponges have all been suggested to contribute to scar formation.90 Meticulous hemostasis and attention to detail are basic surgical principles that can help to improve the likelihood of a good outcome. Surgery as a treatment for postoperative scarring is not beneficial.91

Many interventions have been used for the prevention of perineural scar formation. Epidural corticosteroids have been used for years, and while their use has been supported in animal models, only recently has its benefit been confirmed clinically. It has been shown that their use results in shorter hospital stays, quicker recovery, and a reduction in neurologic deficits in the short-term postoperative period without negative effects.92,93 Long-term benefits and reoperation rates have not been demonstrated. Placement of an epidural fat graft is also commonly used to prevent perineural scar formation. Currently, the supporting data are scarce, but the risk with this technique appears to be low.94,95 Technically, it has been proposed that preserving the ligamentum flavum and performing only a laminotomy could reduce postoperative fibrosis and scarring. While a radiographic reduction in postdiscectomy fibrosis has been seen, the clinical significance is not known.96 Experimental interventions that have been studied include the use of hyaluronic acid and Adcon-L. Hyaluronic acid has been used in non-neurosurgical procedures for the prevention of postoperative scar formation. Histopathologically, it has been shown to decrease scarring in animal models by reducing the influx of inflammatory cells and subsequent cytokine release.95,97 Its efficacy against the perineural scar has not been verified in the clinical setting. Adcon-L is a carbohydrate polymer in gelatin that demonstrated reduced perineural scar formation in both animal histologic and human radiographic studies.98–100 Clinical trials, however, failed to show benefit.101 In addition, it has been associated with cerebrospinal fluid leakage.102,103

Postoperative infections have a frequency of just 0.5% with the discectomy. Predisposing factors include diabetes mellitus, immunocompromised status, steroid use, and elderly or alcoholic patients.89 Intraoperative risk factors that have been identified are prolonged monopolar or retraction use and excessive tissue destruction.89 Patients who develop postoperative infections often present with worsening back pain, increasing muscle spasm, and possibly new deficits. Cauda equina syndrome without a compressive lesion has also been reported.104 Most patients present with these complications within 1 to 4 weeks after surgery (80% within first month), but these complications have been reported as late as 8 months postoperatively.105 Fever and leukocytosis, which might be helpful in establishing the diagnosis, are often absent. Both erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) should be elevated. ESR is quite sensitive to infections, but it is often elevated in the setting of recent surgery and is therefore not specific. CRP is more specific because it usually returns to normal much sooner than the ESR.105,106 Each is most useful when a preoperative baseline is known. Work-up should include an enhanced MRI to evaluate for signs of discitis or epidural abscess.

Treatment of postoperative infections varies based on the severity. As an initial step, the offending organism should be identified. Superficial infections not involving the disc space can be easily drained percutaneously or via an open washout. These infections usually require 1- to 2-week treatment with intravenous antibiotics. Close monitoring for progression of infection is warranted. Treatment of deeper infections involving the disc space is centered on antibiotic therapy against the appropriate organism (most often Staphylococcus sp.).105 Treatment should be continued for at least 6 weeks, and the CRP and ESR should be monitored for evidence of response. If osteomyelitis is present, then treatment should be prolonged. External orthosis is also recommended to protect against secondary instability from destruction of the disc space. If cultures fail to isolate an organism, treatment is less well defined. If no prebiopsy antibiotics were administrated (which will reduce the yield) and no organism can be identified, antimicrobial therapy can be pursued. At our institution, we choose to proceed with antibiotic coverage against gram-positive organisms if the clinical suspicion of infection is quite high. Others have argued for restraint, as the inflammation may instead represent a “mechanical” discitis, which should be treated with rest.107

Outcomes

Fortunately, the natural history of sciatica is a favorable one even without surgery.33,53 Leg pain is expected to resolve within 8 weeks from onset.108–110 The general consensus is that conservative therapy should be initially attempted, although the duration is not known.111–113 Surgical interventions for lumbar discectomy are traditionally very good, but patient selection is paramount.

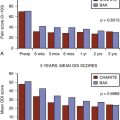

While the standard of surgical care is still the microdiscectomy, with time and the development of new technologies, a shift towards less invasive techniques continues. “Minimally invasive” methods for treating sciatica have gained popularity since they were first described in 1997 by Foley and Smith.114 While their use has increased, data demonstrating their superiority over the standard microdiscectomy are somewhat lacking. In 2009, Arts et al.115 completed a large, multicenter trial comparing conventional microdiscectomy with microendoscopic discectomy. The results demonstrated a statistically significant benefit of conventional microdiscectomy over the microendoscopic discectomy at 1 year in all primary and secondary outcome measures with no difference in complication rates. While these results are unlikely to make the minimally invasive procedures obsolete, they do reaffirm the microdiscectomy as the standard of care for surgical treatment of disc-related sciatica.

Many studies have also been undertaken in an attempt to decide whether the benefit of surgical intervention for sciatica merely reflects the natural history of the disease or if surgery is truly more beneficial than conservative therapies. In 1983, Weber32 demonstrated an early benefit of surgery over conservative therapies; however, no significant improvement was observed with later follow-up. Unfortunately, any study attempting to answer this question will be inherently limited by certain factors. For instance, crossover is practically inevitable as patients (and many physicians) see surgery as a “cure” and can push for surgery if conservative interventions are not thought to be working. This high rate of crossover will bias the results of any randomized trial toward the null. In addition, the inability to blind patients or examiners to intervention can lead to bias. “Sham” or “placebo” surgery is not thought to be feasible because of ethical implications.

Recently, two large, multicenter randomized trials were completed in an attempt to evaluate the outcomes of discectomy versus conservative treatment. The first, by Peul et al.,34 involved 283 patients with 6 to 12 weeks of sciatica randomized to either “early surgery” or continued conservative treatment. Results were reported as “intention to treat,” which demonstrated no benefit at 1 year of either arm. There was, however, quicker relief of all symptoms in the surgery group, with maximum benefit occurring between 8 and 12 weeks. The median time to recovery was 4.0 weeks in the surgery arm and 12.1 weeks in the conservative arm, but by 1 year the results were balanced. Interpretation of these results was limited by a 39% crossover from conservative therapy to surgery and 11% crossover from the surgical arm to continued conservative therapy.

Weinstein et al.68 published the largest randomized controlled trial (SPORT) to date on the subject of surgery versus conservative management for sciatica. When analyzed by “intention to treat,” no significant benefit was found in either intervention for all points of evaluation up to 4 years follow-up. Unfortunately, the SPORT trial was plagued by a troubling incidence of crossover, with 45% in the conservative arm receiving surgery and 41% from the surgical arm electing to not undergo surgery. This led the authors to additionally analyze the results based on an “as treated” analysis, which did strongly favor surgical intervention for all primary and secondary outcomes. The SPORT trial also reported that back pain improved with microdiscectomy.116 However, these results were identified in the secondary analysis, which were also analyzed as “as treated.” Although these findings may indicate a benefit from surgical intervention and are often used to justify surgery for these patients, drawing conclusions based on these results, is methodologically flawed because of the introduction of bias into the study and the actual significance is subject to debate.68

Arts M.P., Brand R., van den Akker M.E., et al. Tubular diskectomy vs conventional microdiskectomy for sciatica: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(2):149-158.

Bärlocher C.B., Krauss J.K., Seiler R.W. Central lumbar disc herniation. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2000;142(12):1369-1374.

Barth M., Deipers M., Weiss C., et al. Two-year outcome after lumbar microdiscectomy versus microscopic sequestrectomy. Part 2: radiographic evaluation and correlation with clinical outcomes. Spine. 2008;33(3):273-279.

Barth M., Weiss C., Thomé C. Two-year outcome after lumbar microdiscectomy versus microscopic sequestrectomy. Part 1: evaluation of clinical outcome. Spine. 2008;33(3):265-272.

Davis R.A. A long-term outcome analysis of 984 surgically treated herniated lumbar discs. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:415-421.

Ehni B.L., Benzel E.D., Biscup R.S.. Lumbar Discectomy, Benzel E.C., editor. Spine Surgery—Techniques, Complication Avoidance, and Management, 2nd ed, vol 1. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2005., pp. 601-618

Epstein N.E. Evaluation of varied surgical approaches used in the management of 170 far-lateral lumbar disc herniations: indications and results. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:648-656.

Errico T.J., Fardon D.F., Lowell T.D. Open discectomy as treatment for herniated nucleus pulposus of the lumbar spine. Spine. 1995;20:1829-1833.

Garrido E., Connaughton P.N. Unilateral facetectomy approach for lateral lumbar disc herniations. J Neurosurg. 1991;74:754-756.

Hood R.S. Far lateral lumbar disc herniations. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1993;4(1):117-124.

Ito T., Takano Y., Yuasa N. Types of lumbar herniated disc and clinical course. Spine. 2001;26:648-651.

Keskimaki I., Seitsalo S., Osterman H., et al. Reoperations after lumbar disc surgery: a population-based study of regional and interspecialty variations. Spine. 2000;25:1500-1508.

McCulloch J.A. Focus issue on lumbar disc herniation: macro- and microdiscectomy. Spine. 1996;21:45S-56S.

McGirt M.J., Ambrossi G.L., Datoo G., et al. Recurrent disc herniation and long-term back pain after primary lumbar discectomy: review of outcomes reported for limited versus aggressive disc removal. Neurosurgery. 2009;64(2):338-344.

Mixter W.J., Barr J.S. Rupture of the intervertebral disc with involvement of the spinal canal. N Engl J Med. 1934;211:210-214.

Ohmori K., Kanamori M., Kawaguchi Y., et al. Clinical features of extraforaminal lumbar disc herniation based on the radiographic location of the dorsal root ganglion. Spine. 2001;26:662-666.

Pearson A.M., Blood E.A., Frymoyer J.W., et al. SPORT lumbar intervertebral disk herniation and back pain: does treatment, location, or morphology matter? Spine. 2008;33(4):428-435.

Peul W.C., van Houwelingen H.C., van den Hout W.B., et al. Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(22):2245-2256.

Räsmussen S., Krum-Møller D.S., Lauridsen L.R. Epidural steroid following discectomy for herniated lumbar disc reduces neurological impairment and enhances recovery: a randomized study with two-year follow-up. Spine. 2008;33(19):2028-2033.

Rönnberg K., Lind B., Zoega B., et al. Peridural scar and its relation to clinical outcome: a randomised study on surgically treated lumbar disc herniation patients. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(12):1714-1720.

Schick U., Elhabony R. Prospective comparative study of lumbar sequestrectomy and microdiscectomy. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2009;52(4):180-185.

Suk K., Lee H., Moon S. Recurrent disc herniation: results of operative management. Spine. 2001;26:672-676.

Weber H. Lumbar disc herniation: a controlled prospective study with ten years of observation. Spine. 1983;8:131-140.

Weber H. The natural history of disc herniation and the influence of intervention. Spine. 1994;19:2234-2238.

Weinstein J.N., Lurie J.D., Tosteson T.D., et al. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: four-year results for the spine patient outcomes research trial (SPORT). Spine. 2008;33(25):2789-2800.

1. Witham T.H., Gokaslan Z.L. Lumbar disc herniations—to operate or not to operate? Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007;3(6):316-317.

2. Viets H. Dominico Cotugno: his description of the cerebral spinal fluid, with a translation of part of his De Ischiade Nervosa Commentarius (1764) and a bibliography of his important works. Bull Inst Hist Med. 1935;3:701-738.

3. Pott P. Remarks on that kind of palsy of the lower limbs which frequently found to accompany a curvature of the spine, and is supposed to be caused by it, together with its method of curve. Med Classics. 1936;1:281-297.

4. Dandy W.E. Loose cartilage from the intervertebral disc simulating tumor of the spinal cord. Arch Surg. 1929;19:660-672.

5. Mixter W.J., Barr J.S. Rupture of the intervertebral disc with involvement of the spinal canal. N Engl J Med. 1934;211:210-214.

6. Parisien R., Ball P. Historical perspective: William Jason Mixter (1880–1958): ushering in the “dynasty of the disc.”. Spine. 1998;23:2363-2366.

7. Roughley P.J. Biology of intervertebral disc aging and degeneration. Spine. 2004;29:2691-2699.

8. Setton L.A., Chen J. Cell mechanics and mechanobiology in the intervertebral disc. Spine. 2004;29:2710-2723.

9. Kramer J. Intervertebral Disc Diseases: Causes, Diagnosis, Treatment and Prophylaxis, 2nd ed. New York: Thieme; 1990.

10. Tarlov E.C., Magge S.. Microsurgery of ruptured lumbar intervertebral disc, Schmidek H.H., Roberts D.W., editors. Schmidek & Sweet’s Operative Neurosurgical Techniques: Indications, Methods, and Results, 5th ed, vol 2. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2006;2055-2071.

11. Abdullah A.F., Ditto E.W., Byrd E.B., et al. Surgical management of extreme lateral lumbar disc herniations: review of 138 cases. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:648-653.

12. Garrido E., Connaughton P.N. Unilateral facetectomy approach for lateral lumbar disc herniations. J Neurosurg. 1991;74:754-756.

13. Boden S.D., Davis D.O., Dina T.S., et al. Abnormal magnetic resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects: a prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;72:403-408.

14. Olmarker K., Holm S., Rosenqvist A.L., et al. Experimental nerve root compression. A model of acute, graded compression of the porcine cauda equina and as analysis of neural and vascular anatomy. Spine. 1991;16:61-69.

15. Saal J.S., Franson R.C., Dobrow R., et al. High levels of inflammatory phospholipase A2 activity in the lumbar disc herniations. Spine. 1990;15:674-678.

16. Jarvik J.G., Deyo R.A. Imaging of lumbar intervertebral disc degeneration and aging, excluding disc herniations. Radiol Clin Am. 2000;38:1255-1266. vi

17. Kendrick D., Fielding K., Bentley E., et al. Radiography of the lumbar spine in primary care patients with low back pain: randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2001;322:400-405.

18. Luoma K., Riihimaki H., Luukkonen R., et al. Low back pain in relation to lumbar disc degeneration. Spine. 2000;25:487-492.

19. Borenstein D.G. Epidemiology, etiology, diagnostic evaluation, and treatment of low back pain. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2001;13:128-134.

20. McCulloch J.A. Focus issue on lumbar disc herniation: macro- and microdiscectomy. Spine. 1996;21:45S-56S.

21. Albeck M.J. A critical assessment of clinical diagnosis of disc herniation in patients with monoradicular sciatica. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1996;138:40-44.

22. Stankovic R., Johnell O., Maly P., et al. Use of lumbar extension, slump test, physical and neurological examination in the evaluation of patients with suspected herniated nucleus pulposus: a prospective study. Man Ther. 1999;4:25-32.

23. Vucetic N., de Bri E., Svensson O. Clinical history in lumbar disc herniation: a prospective study in 160 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 1997;68:116-120.

24. Vucetic N., Svensson O.. Physical signs in lumbar disc hernia. Clin Orthop Relat Res, 1996;333:192-201

25. Ohmori K., Kanamori M., Kawaguchi Y., et al. Clinical features of extraforaminal lumbar disc herniation based on the radiographic location of the dorsal root ganglion. Spine. 2001;26:662-666.

26. Shapiro S. Medical realities of cauda equina syndrome secondary to lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 2000;25:348-352.

27. Kostuik J.P., Harringtion I., Alexander D., et al. Cauda equina syndrome and lumbar disc herniation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:386-391.

28. Gleave J., Macfarlane R. Prognosis for recovery of bladder function following lumbar central disc prolapse. Br J Neurosurg. 1990;4:205-210.

29. Vroomen P.C., de Krom M.C., Wilmink J.T. Pathoanatomy of clinical findings in patients with sciatica a magnetic resonance imaging study. J Neurosurg. 2000;92:135-141.

30. Atlas S.J., Deyo R.A., Keller R.B., et al. The Main Lumbar Spine Study. Part II: 1-year outcomes of surgical and nonsurgical management of sciatica. Spine. 1996;21:1777-1786.

31. Ito T., Takano Y., Yuasa N. Types of lumbar herniated disc and clinical course. Spine. 2001;26:648-651.

32. Weber H. Lumbar disc herniation: a controlled prospective study with ten years of observation. Spine. 1983;8:131-140.

33. Weber H. The natural history of disc herniation and the influence of intervention. Spine. 1994;19:2234-2238.

34. Peul W.C., van Houwelingen H.C., van den Hout W.B., et al. Surgery versus prolonged conservative treatment for sciatica. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(22):2245-2256.

35. Errico T.J., Fardon D.F., Lowell T.D. Open discectomy as treatment for herniated nucleus pulposus of the lumbar spine. Spine. 1995;20:1829-1833.

36. Hall H. Surgery: indications and options. Neurol Clin. 1999;17:113-130.

37. Ito T., Yamada M., Ikuta F., et al. Histologic evidence of absorption of sequestration-type herniated disc. Spine. 1996;21:230-234.

38. Maigne J.Y., Rime B., Deligne B. Computed tomographic follow-up study of forty-eight cases of nonoperatively treated lumbar intervertebral disc herniation. Spine. 1992;17:1071-1074.

39. Ozaki S., Muro T., Ito S., et al. Neovascularization of the outermost area of herniated lumbar intervertebral discs. J Orthop Sci. 1999;4:286-292.

40. Rohan M.X.Jr., Ohnmeiss D.D., Guyer R.D., et al. Relationship between the length of time off work preoperatively and clinical outcome at 24-month follow-up in patients undergoing total disc replacement or fusion. Spine. 2008;9(5):360-365.

41. Vroomen P.C., de Krom M.C., Knottnerus J.A. When does the patient with a disc herniation undergo lumbosacral discectomy? J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2000;68:75-79.

42. Eysel P., Rompe J.D., Hopf C. Prognostic criteria of discogenic paresis. Eur Spine J. 1994;3:214-218.

43. Haines S.J. Systemic antibiotic prophylaxis in neurological surgery. Neurosurgery. 1980;6:355-361.

44. Henriksen L., Schmidt K., Eskesen V., et al. A controlled study of microsurgical versus standard lumbar discectomy. Br J Neurosurg. 1996;10(3):289-293.

45. Porchet F., Bartanusz V., Kleinstueck F.S., et al. Microdiscectomy compared with standard discectomy: an old problem revisited with new outcome measures within the framework of a spine surgical registry. Eur Spine J. 2009;18(Suppl 3):360-366.

46. Katz D.M., Trobe J.D., Cornbluth W.T., et al. The Maine Lumbar Spine Study. Part I: background and concepts. Spine. 1996;21:1769-1776.

47. Rigamonti, Gemma M., Rocca A., et al. Prone versus knee-chest position for microdiscectomy: a prospective randomized study of intra-abdominal pressure and intraoperative bleeding. Spine. 2005;30(17):1918-1923.

48. Bärlocher C.B., Krauss J.K., Seiler R.W. Central lumbar disc herniation. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2000;142(12):1369-1374.

49. Schick U., Elhabony R. Prospective comparative study of lumbar sequestrectomy and microdiscectomy. Minim Invasive Neurosurg. 2009;52(4):180-185.

50. Barth M., Weiss C., Thomé C. Two-year outcome after lumbar microdiscectomy versus microscopic sequestrectomy: part 1: evaluation of clinical outcome. Spine. 2008;33(3):265-272.

51. Barth M., Deipers M., Weiss C., et al. Two-year outcome after lumbar microdiscectomy versus microscopic sequestrectomy: part 2: radiographic evaluation and correlation with clinical outcomes. Spine. 2008;33(3):273-279.

52. Fountas K.N., Kapsalaki E.Z., Feltes C.H., et al. Correlation of the amount of disc removed in a lumbar microdiscectomy with long-term outcome. Spine. 2004;29(22):2521-2524.

53. McGirt M.J., Ambrossi G.L., Datoo G., et al. Recurrent disc herniation and long-term back pain after primary lumbar discectomy: review of outcomes reported for limited versus aggressive disc removal. Neurosurgery. 2009;64(2):338-344.

54. Jensen R.L. Cauda equina syndrome as a postoperative complication of lumbar spine surgery. Neurosurg Focus. 2004;16(6):e7.

55. Hood R.S. Far lateral lumbar disc herniations. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1993;4(1):117-124.

56. Abdullah A.F., Wolber P.G.H., Warfield J.R., et al. Surgical management of extreme lateral lumbar disc herniations: review of 138 cases. Neurosurgery. 1988;22:648-653.

57. Porchet F., Fankhauser H., de Tribolet N. Extreme lateral lumbar disc herniation: clinical presentation in 178 patients. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1994;127(3-4):203-209.

58. Donaldson W.F.III, Star M.J., Thorne R.P. Surgical treatment for the far lateral lumbar disc. Spine. 1993;18:1263-1267.

59. Epstein N.E. Evaluation of varied surgical approaches used in the management of 170 far-lateral lumbar disc herniations: indications and results. J Neurosurg. 1995;83:648-656.

60. Müller A., Hans-Jürgen R. A paramedian tangential approach to lumbosacral extraforaminal disc herniations. Neurosurgery. 1998;43(4):854-861.

61. Larson S.J., Holst R.A., Hemmy D.C., et al. Lateral extracavitary approach to traumatic lesions of the thoracic and lumbar spine. J Neurosurg. 1976;45:628-637.

62. Lanzino G., Shaffrey C.I., Jane J.A.. Surgical treatment of lateral lumbar herniated discs, Rengachary S.S., Wilkins R.H., editors, Neurosurgical Operative Atlas, Park Ridge, IL, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, 1999;vol 8:243-251.

63. Brock M., Kunkel P., Papavero L. Lumbar microdiscectomy: subperiosteal versus transmuscular approach and influence on the early postoperative analgesic consumption. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(4):518-522.

64. Abramovitz J.N., Neff S.R. Lumbar disc surgery: results of the Prospective Lumbar Discectomy Study of the Joint Section on Disorders of the Spine and Peripheral Nerves of the Congress of Neurological Surgeons. Neurosurgery. 1991;29:301-307.

65. Rosen C., Rothman S., Zigler J., et al. Lumbar facet fracture as a possible source of pain after lumbar laminectomy. Spine. 1991;16:S234-S238.

66. Jenis L.G., An H.S., Gordin R. Spine update: lumbar foraminal stenosis. Spine. 2000;25:389-394.

67. Kalfas I.H. Principles of bone healing. Neurosurg Focus. 2001;10(4):1-4.

68. Weinstein J.N., Lurie J.D., Tosteson T.D., et al. Surgical versus nonoperative treatment for lumbar disc herniation: four-year results for the spine patient outcomes research trial (SPORT). Spine. 2008;33(25):2789-2800.

69. Lee K.S., Hardy I.M.II. Postlaminectomy lumbar pseudomeningocele: a report of four cases. Neurosurgery. 1992;30:111-114.

70. Nishi S., Hashimoto N., Takagi Y., et al. Herniation and entrapment of a nerve root secondary to an unrepaired small dural laceration at lumbar hemilaminectomies. Spine. 1995;20:2576-2579.

71. Tsuji H., Handa N., Handa O., et al. Postlaminectomy ossified extradural pseudocyst: a case report. J Neurosurg. 1990;73:785-787.

72. deFreitas D.J., McCabe J.P. Acinetobacter baumanii meningitis: a rare complication of incidental durotomy. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2004;17(2):115-116.

73. Goodkin R., Laska L.L. Vascular and visceral injuries associated with lumbar disc surgery: medical implications. Surg Neurol. 1998;49:358-370.

74. Montorsi W., Ghiringhelli C. Genesis, diagnosis and treatment of vascular complications after intervertebral disc surgery. Int Surg. 1973;58:233-235.

75. DeSaussure R.L. Vascular injury coincident to disc surgery. J Neurosurg. 1959;16:222-229.

76. Sadhasivam S., Kaynar A.M. Iatrogenic arteriovenous fistula during lumbar microdiscectomy. Anesth Analg. 2004;99(6):1815-1817.

77. Kwon T.W., Sung K.B., Cho Y.P., et al. Large vessel injury following operation for a herniated lumbar disc. Ann Vasc Surg. 2003;17(4):438-444.

78. Turner J.A., Ersek M., Herron L., et al. Patient outcome after lumbar spinal fusions. JAMA. 1992;268:907-911.

79. Davis R.A. A long-term outcome analysis of 984 surgically treated herniated lumbar discs. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:415-421.

80. Keskimaki I., Seitsalo S., Osterman H., et al. Reoperations after lumbar disc surgery: a population-based study of regional and interspecialty variations. Spine. 2000;25:1500-1508.

81. Malter A.D., McNeney B., Loeser J.D., et al. 5-year reoperation rates after different types of lumbar spine surgery. Spine. 1998;23:814-820.

82. Jönsson B., Strömqvist B. Clinical characteristics of recurrent sciatica after lumbar discectomy. Spine. 1996;21:500-505.

83. Suk K., Lee H., Moon S. Recurrent disc herniation: results of operative management. Spine. 2001;26:672-676.

84. Herron L. Recurrent lumbar disc herniation: results of repeat laminectomy and discectomy. J Spinal Disord Tech. 1994;7:161-166.

85. Fritsch E.W., Heisel J., Rupp S. The failed back surgery syndrome: reasons, intraoperative findings, and long-term results: a report of 182 operative treatments. Spine. 1996;21:626-633.

86. Ross J.S., Robertson J.T., Frederickson R.C., et al. Association between peridural scar and recurrent radicular pain after lumbar discectomy: magnetic resonance evaluation. ADCON-L European Study Group. Neurosurgery. 1996;38:855-863.

87. Schisano G., Franco A., Nina P.L. Intraradicular and intradural lumbar disc herniation: experience with nine cases. Surg Neurol. 1995;44:536-543.

88. Suzer T., Tahta K., Coskun E. Intraradicular lumbar disc herniation: case report and review of the literature. Neurosurgery. 1997;41:956-958.

89. Ehni B.L., Benzel E.C., Biscup R.S.. Lumbar Discectomy, Benzel E.C., editor. Spine Surgery—Techniques, Complication Avoidance, and Management, 2nd ed, vol 1. Philadelphia: Saunders, 2005. pp. 601-618

90. Ceviz A., Arslan A., Ak H.E., et al. The effect of urokinase in preventing the formation of epidural fibrosis and/or leptomeningeal arachnoiditis. Surg Neurol. 1997;47:124-127.

91. Fiume D., Sherkat S., Callovini G.M., et al. Treatment of the failed back surgery syndrome due to lumbo-sacral epidural fibrosis. Acta Neurochir Suppl (Wien). 1995;64:116-118.

92. Räsmussen S., Krum-Møller D.S., Lauridsen L.R. Epidural steroid following discectomy for herniated lumbar disc reduces neurological impairment and enhances recovery: a randomized study with two-year follow-up. Spine. 2008;33(19):2028-2033.

93. Modi H., Chung K.J., Yoon H.S. Local application of low-dose Depo-Medrol is effective in reducing immediate postoperative back pain. Int Orthop. 2009;33(3):737-743.

94. MacKay M.A., Fischgrund J.S., Herkowitz H.N., et al. The effect of interposition membrane on the outcome of the lumbar laminectomy and discectomy. Spine. 1995;20:1793-1796.

95. Songer M.N., Rauschning W., Carson E.W., et al. Analysis of peridural scar formation and its prevention after lumbar laminectomy and discectomy in dogs. Spine. 1995;20:571-580.

96. Ozer A.F., Oktenoglu T., Sasani M., et al. Preserving the ligamentum flavum in lumbar discectomy: a new technique that prevents scar tissue formation in the first 6 months postsurgery. Neurosurgery. 2006;59(1 Suppl 1):ONS126-ONS133.

97. Schimizzi A.L., Massie J.B., Murphy M., et al. High-molecular-weight hyaluronan inhibits macrophage proliferation and cytokine release in the early wound of a preclinical postlaminectomy rat model. Spine J. 2006;6(5):550-556.

98. Brotchi J., Pirotte B., De Witte O., et al. Prevention of epidural fibrosis in a prospective series of 100 primary lumbo-sacral discectomy patients: follow-up and assessment at re-operation. Neurol Res. 1999;21(suppl 1):S47-S50.

99. Fischgrund J.S. Perspectives on modern orthopaedics: use of Adcon-L for epidural scar prevention. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8:339-343.

100. Robertson J.T., Maier K., Anderson R.W., et al. Prevention of epidural fibrosis with ADCON-L in presence of a durotomy during lumbar disc surgery: experiences with a pre-clinical model. Neurol Res. 1999;21(suppl 1):S61-S66.

101. Rönnberg K., Lind B., Zoega B., et al. Peridural scar and its relation to clinical outcome: a randomised study on surgically treated lumbar disc herniation patients. Eur Spine J. 2008;17(12):1714-1720.

102. Hieb L.D., Stevens D.L. Spontaneous postoperative cerebrospinal fluid leaks following application of anti-adhesion barrier gel: case report and review of literature. Spine. 2001;26:748-751.

103. Le A.X., Rogers D.E., Dawson E.G., et al. Unrecognized durotomy after lumbar discectomy: a report of four cases associated with the use of ADCON-L. Spine. 2001;26:115-117.

104. Arend S.M., Steenmeyer A.V., Mosmans P.C., et al. Postoperative cauda syndrome caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Infection. 1993;21:248-250.

105. Rawlings C.E., Wilkins R.H., Gallis H.A., et al. Postoperative intervertebral disc space infection. Neurosurgery. 1983;13:371-376.

106. Thelander U., Larsson S. Quantitation of C-reactive protein levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rate after spinal surgery. Spine. 1992;17:400-404.

107. Fouquet B., Goupille P., Jattiot F., et al. Discitis after lumbar disc surgery: features of “aseptic” and “septic” forms. Spine. 1992;17:356-358.

108. Vroomen P.C., de Krom M.C., Wilmink J.T., et al. Lack of effectiveness of bed rest for sciatica. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:418-423.

109. Hofstee D.J., Gijtenbeek J.M., Hoogland P.H., et al. Westeinde sciatica trial: randomized controlled study of bed rest and physiotherapy for acute sciatica. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(suppl 1):45-49.

110. Awad J.N., Moskovich R. Lumbar disc herniations: surgical versus nonsurgical treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;443:183-197.

111. Andersson G.B., Brown M.D., Dvorak J., et al. Consensus summary of the diagnosis and treatment of lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 1996;21(suppl):75S-78S.

112. Luijsterburg P.A., Verhagen A.P., Braak S., et al. Do neurosurgeons subscribe to the guideline lumbosacral radicular syndrome? Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2004;106:313-317.

113. Vader J.P., Porchet F., Larequi-Lauber T., Dubois, et al. Appropriateness of surgery for sciatica: reliability of guidelines from expert panels. Spine. 2000;25:1831-1836.

114. Foley K.T., Smith M.M. Microendoscopic discectomy. Tech Neurosurg. 1997;3:301-307.

115. Arts M.P., Brand R., van den Akker M.E., et al. Tubular diskectomy vs conventional microdiskectomy for sciatica: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;302(2):149-158.

116. Pearson A.M., Blood E.A., Frymoyer J.W., et al. SPORT lumbar intervertebral disk herniation and back pain: does treatment, location, or morphology matter? Spine. 2008;33(4):428-435.