CHAPTER 89 Lumbar Axial Pain – An Algorithmic Methodology

INTRODUCTION

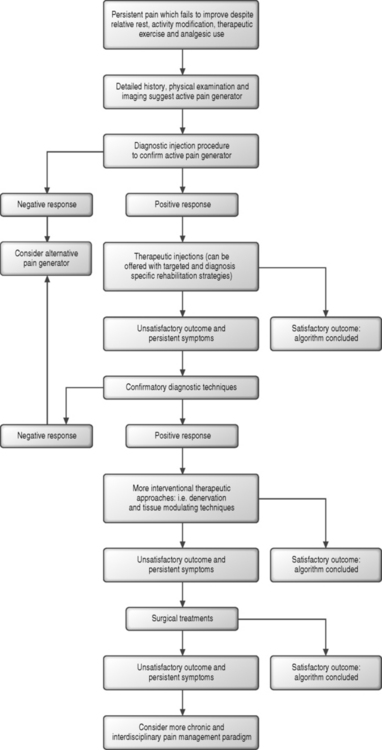

Promoting an algorithmic approach to the patient with lumbar axial pain may at first appear paradoxical. Algorithms imply a defined if not mathematical process, yet lumbar pain generators are often multifactorial and elusive. It is actually the clandestine nature of the lumbar axial pain generator and the often speculative diagnoses assigned to patients with persistent lumbar pain which warrant a more methodological diagnostic and therapeutic approach. This chapter is written in the context of an interventional spine text. The minority of patients with lumbar pain will require an interventional approach. While remarkably prevalent, most episodes of debilitating axial pain will prove short lived. The majority of patients will respond to a period of activity modification. Some will participate in a structured rehabilitation program and utilize oral analgesics or antiinflammatory agents in order to realize relief. It is the relative minority of patients whose axial pain persists in a debilitating fashion who are candidates for an interventional approach. In such cases, a more meticulous history, examination, and image review can offer guidelines for the judicious use of diagnostic and therapeutic spinal injection procedures. Spinal pain generators are typically not definitively identified by history, highlighted by imaging, or reliably provoked during physical examination. While it is always the goal to treat in a less interventional fashion, in the case of persistent lumbar axial pain, diagnostic injection techniques offer an opportunity to identify pain generators in this patient population where diagnoses might otherwise remain ill defined. Offering these challenging patients further therapeutic interventions before exhausting a more algorithmic diagnostic approach might lead the patient along a less appropriate and ineffective treatment pathway.

Once a pain generator is confirmed through completion of the diagnostic component of the algorithm, therapeutic approaches should also be considered in a logical fashion. Arguably, one’s ability to identify the origin of pain through an interventional approach, which in itself remains inexact and incomplete, remains superior and less controversial than the efficacy of the therapeutic options available to the interventionist. Less interventional treatments, defined as those which strive to reduce pain and inflammation, but maintain tissue integrity, should be offered prior to those that denervate, ablate, modulate tissue, resect or alter regional anatomy and function. When therapeutic corticosteroid injections are performed, it is the author’s practice to schedule two injections 2 weeks apart. If the first injection offers complete relief, the second is deferred. If no relief is offered after two injections, injection therapy is determined likely to be ineffective. If a component of lasting, but incomplete relief is described 2 weeks after the second injection, a third is offered. A fourth and final injection is only considered for those patients who describe an incremental and sustained response to the initial three. Injection series are ideally not repeated, but if offered in the future, this does not transpire until 6–12 months after the initial series. This number of injection procedures described finds its basis in part in a review of the literature describing the role of therapeutic epidural injections in the treatment of lumbosacral radiculopathy.1 With an increasing number of injections performed, declining therapeutic efficacy and potential local and systemic adverse corticosteroid effect should raise greater concerns.2 As more interventional and less reversible therapeutic approaches are entertained, additional and confirmatory diagnostics can be utilized to assure accurate identification of the pain generator. For those patients who ultimately fail to realize relief following an algorithmic approach or who are determined to be poor surgical candidates, a paradigm better related to chronic pain modulation is proposed. The chronic pain program can employ the use of analgesics, alternative maintenance therapies such as acupuncture and biofeedback, pyschological care, and, in select cases, a consideration of implantable pain modulating devices (Fig. 89.1).

Ultimately, the patient with persistent and debilitating axial pain presents the spine specialist with unique and formidable bookend challenges. The diagnostic algorithm can prove multifaceted with initially suspected pain generators ultimately found to be inert. The therapeutic arm of the axial pain algorithm remains hindered by a general lack of more conclusively supportive and well-designed outcome studies. The common disorder of persistent axial pain continues to challenge the many disciplines of the spine care community, and the multitude of current studies examining therapeutic approaches reflects the ongoing search for more definitive treatments. This chapter will address several syndromes, which are the topic of other dedicated chapters in this text. In these dedicated chapters, meticulous descriptions of procedural techniques and a more complete review of the pertinent literature have been included. In each of the following sections, background information pertaining to the pain generator of interest will be provided first. The significance of radiographic studies, patient history, and physical examination findings will then be discussed with an inclusion of supportive literature and the author’s practice in each realm. A diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm will then be presented in a logical and sequential fashion and summarized in figure form. The chapter will conclude with a mention of axial pain of potential radicular origin, more malignant processes which can lead to axial pain, and finally, two exemplary cases in which an algorithmic approach is employed.

SACROILIAC JOINT

The sacroiliac joint (SIJ) will be addressed first, as sacroiliac joint syndrome (SIJS) remains a commonly assigned diagnosis for the patient with axial pain. Prior to Mixter and Barr’s 1934 study highlighting pathology of the intervertebral disc,3 the SIJ was believed to represent the most likely pain generator in patients with low back pain. As with the other anatomic structures addressed in this chapter, the SIJ remains a viable candidate for a primary pain generator as it satisfies several criteria outlined elsewhere: first, the structure should have a nerve supply; second, it should be susceptible to diseases or injuries known to be painful; and third, it should be capable of causing pain similar to that seen clinically.4 The complex and variable innervation of the SIJ has been described in many anatomic studies.4–6 Painful SIJ conditions are known to arise from spondylarthropathies,7 infection,8 trauma,9,10 and malignancy.11 Intra-articular injections, performed both provocatively in asymptomatics12 and diagnostically in patients with chronic lumbar pain,13,14 have demonstrated the SIJ to be a potential source of pain. The prevalence of SIJS in the population with chronic low back pain has been estimated at 13–30%.13,14 SIJS, which remains a controversial diagnosis among spine practitioners, has been hypothesized to develop from degenerative change affecting the joint or altered joint mobility. The SIJ is mobile, albeit limited to 3° of rotation and only a few millimeters of glide.15,16

Radiologic or surgical pathology has not been identified in patients with SIJS, further raising pathophysiologic speculation. Bone scan has demonstrated a poor sensitivity (12.9%) in patients demonstrating a positive response to diagnostic intra-articular injections.17 Bone scan has demonstrated a sensitivity in patients with SIJS which is significantly lower than that observed when utilized to detect sacroiliitis in patients with rheumatological disease.17–20 These findings do not exclude the possibility that SIJS does not involve more mild synovial irritation which remains undetected by radionuclide imaging which relies upon an acceleration of osteoblastic activity.17 While magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has demonstrated a high sensitivity in cases of true sacroiliitis,18,19 the role of MRI in diagnosing SIJS has also yet to be defined. At least 24.5% of asymptomatics >50 years of age demonstrate degenerative SIJ changes on plain radiographs,21,22 and similar degenerative findings in aging asymptomatics have been demonstrated utilizing computed tomography (CT) imaging.23 Similarly, no specific pathology has been described in patients undergoing surgical intervention for chronic sacroiliac joint pain.24

Sacroiliac joint pain referral patterns often localize to the sacral sulcus and buttock,12 but patients can also describe symptom referral to the medial thigh and groin,13,25–28 posterior thigh, and calf.9,13,29–31 Physical exam maneuvers utilized to detect motion irregularities have demonstrated poor intertester reliability32,33 and have been observed to be positive in 20% of asymptomatics.34 The detection of joint motion abnormalities by physical examination,29 response to pain provocation tests such as Faber’s and Gaenslen’s maneuvers,17,29,35 and historical findings13,29 have all correlated poorly with the response to fluoroscopically guided diagnostic intra-articular injections, which have come to be recognized as the gold standard for diagnosing SIJ pain. As specific history, examination, and imaging findings have all correlated poorly with a positive response to a diagnostic intra-articular injection, it is more likely a combination of presenting factors which might lead the treating clinician to suspect the SIJ as an active pain generator and warrant introduction into the SIJ diagnostic and therapeutic algorithm. Suggestive symptoms include pain predominantly below the L5 level in the region of the sacral sulcus, with or without referral to the groin13 or more distal lower limb, and sacral sulcus tenderness to palpation.29,35,36 Additionally, patients with unilateral symptoms and a positive response to multiple provocative maneuvers may be more likely to demonstrate a positive diagnostic injection response and subsequently benefit from targeted therapeutic approaches.29,35,36 While a previous history of a fall upon the affected buttock, recent pregnancy, pelvic trauma, or an antecedent gait alteration37 also prompt this author to consider the SIJ as a pain generator, these historical points have not been demonstrated to be predictive by the available literature.

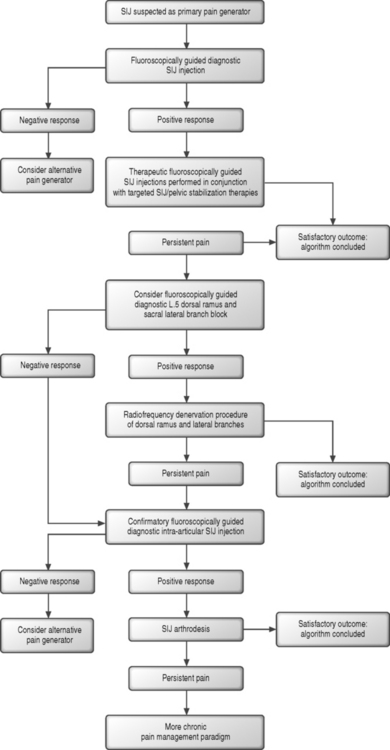

For those patients who are believed to be reasonable candidates, an algorithmic approach to the SIJ (Fig. 89.2) can be initiated and a confirmatory diagnostic SIJ injection performed. Diagnostic intra-articular injections were initially described in 1938,38 and the utilization of fluoroscopic guidance was first introduced in 1979.39 It has been estimated that successful intra-articular SIJ entry is achieved in only 22% of injections performed without image guidance,40 and such blind injections performed for either diagnostic or therapeutic purposes are not included in an algorithmic approach to SIJS. Given the complexity of the anatomy and configuration of the SIJ, it would seem that this 22% figure may even be an overestimate, further amplifying the requirement of using fluoroscopic guidance. If a positive response to a guided diagnostic injection is realized, therapeutic injections should follow. Therapeutic SIJ corticosteroid injections have been advocated as an appropriate treatment for patients with persistent SIJ pain.41 A retrospective and uncontrolled study of SIJ injections in 31 patients with chronic pain of SIJ origin has suggested a lasting resultant improvement in pain, work status, and disability.42 The efficacy of these injections has been more clearly demonstrated, both prospectively and retrospectively and in a controlled fashion, in the seronegative spondyloarthropathy population.43,44 The mechanism of action of injections in patients with presumed SIJS outside of the spondyloarthropathy population remains less clear, but is presumed to arise from the well-known antiinflammatory properties of corticosteroids.28,45 The role of inflammation in SIJS remains unconfirmed. The role of injection therapy in this patient population therefore remains poorly defined. Injection therapy can be combined with a targeted physical therapy regimen which emphasizes pelvic stabilization techniques and SIJ-specific therapies.

For those patients who fail to respond to therapeutic injections, a more recently described and evolving radiofrequency denervation approach to the SIJ might then be considered. The nerves which can be targeted for this approach include the L5 dorsal ramus and the lateral branches of S1–3.46 The ability to reliably target and anesthetize these nerves with fluoroscopic guidance remains less clear.47 In those patients who demonstrate a positive diagnostic response to anesthetization of these innervating branches or who demonstrate a concordant response48 with lateral branch stimulation, a denervation procedure can be trialed. The ability of such a denervation approach to successfully anesthetize the SIJ remains less clear with only small and uncontrolled studies suggesting a significant therapeutic response.49–52

For those patients with persistently debilitating SIJ pain who either fail to respond to denervation techniques or who demonstrate an initial negative response to L5 dorsal ramus and sacral lateral branch anesthetization, surgical arthrodesis of the SIJ can be considered as a final treatment option.50,53 In selecting candidates for SIJ fusion, those patients who demonstrated both a positive lateral branch response and an initial diagnostic intra-articular injection may be considered less likely to be false-positive SIJ patients. In these cases, it would appear that a confirmatory diagnostic injection has been employed to lessen the likelihood of an initial placebo response. As the approach to and efficacy of lateral branch anesthetization remains less well defined, any patient contemplating SIJ fusion should first demonstrate a second positive response to a confirmatory diagnostic intra-articular injection utilizing an anesthetic of different duration or a blind and placebo-controlled diagnostic injection protocol. As well, the candidacy of such individuals for surgical intervention might be further strengthened by a negative response to provocation discography.

ZYGAPOPHYSEAL JOINT

The zygapophyseal joints (Z-joints) have been recognized as a potential source of lumbar pain since 1911.54 The lumbar Z-joints are paired synovial joints with an intra-articular volume capacity of 1–2 mm.55 While the more cephalad lumbar Z-joint orientation tends to be in the sagittal plane, the lower joints are more coronally situated.56 Each lumbar Z-joint is innervated by the medial branch of the dorsal ramus at the level of the joint and by the medial branch arising from the dorsal ramus of the next cephalad level.57 In 1976, Mooney and Robertson58 demonstrated that lumbar axial pain and symptoms referred to the extremity could arise from intra-articular injections of normal saline in asymptomatic volunteers. McCall et al.59 later corroborated these findings and observed a more intense pain response with injection into the capsular tissues when compared with injection into the joint’s intra-articular space. Utilizing progressive local anesthesia during surgery, Kuslich et al.60 demonstrated a pain response with stimulation of the Z-joint capsule, but the pain described by patients was often not concordant with their more debilitating axial pain. Z-joint pain, or ‘facet syndrome,’ is presumed to arise from osteoarthritic change, chondromalacia, or occult fractures.61–66 Less common conditions affecting the Z-joints including infection, ankylosing spondylitis, and villonodular synovitis have also been reported.67,68 Lumbar Z-joint fractures, capsular tears, hemorrhage, and cartilaginous injury have been observed in postmortem studies of trauma patients with normal radiographs.66 A study of 176 consecutive patients presenting with chronic lumbar pain, in which lidocaine and confirmatory bupivacaine medial branch or intra-articular diagnostic injections were employed, suggests that the Z-joint represents the primary pain generator in 15% of cases.69 Plain radiographs often reveal degenerative arthrosis of the Z-joints which strongly correlates with age, but not with symptoms of axial pain.70,71 Utilizing diagnostic intra-articular injections, degenerative Z-joint change detected by CT imaging has also demonstrated a poor correlation with pain arising from the lumbar Z-joints.72

Several studies73–75 have specifically investigated the historical and physical examination findings which might predict the Z-joint as a pain generator. In one of these studies74 a second and confirmatory diagnostic Z-joint injection was included to establish a diagnosis, and in two73,75 a positive response to only a single diagnostic injection was utilized. Patients with confirmed primary Z-joint pain were noted to describe lumbar discomfort, but pain could similarly be referred to the lower limb. Patients generally did not describe central lumbar pain. While no particular symptoms or historical findings demonstrated a significant correlation with a positive response to diagnostic injections, patients with Z-joint pain tended to be older, without exacerbations during coughing, and without described provocation with forward flexed postures. The L5–S1 Z-joints were found to be more likely symptomatic than L4–5, with pain arising from the L3–4 and L2–3 joints much less commonly observed.69 While eliciting a concordant pain response by direct articular palpation has been described as a potential screening mechanism in patients with suspected Z-joint pain,61 the utility of this examination technique was not clearly substantiated by the aforementioned studies.

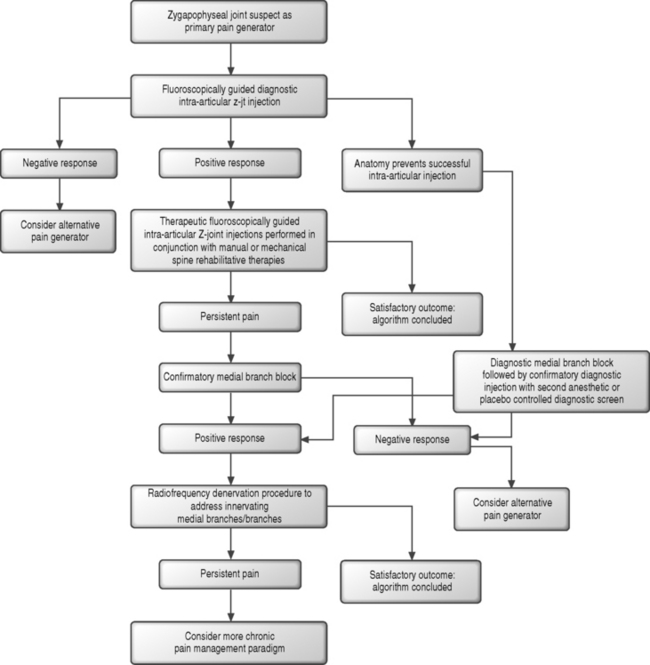

In the patient with suspected Z-joint pain, an algorithmic approach can be initiated (Fig. 89.3) and a confirmatory diagnostic intra-articular injection performed.69,74 There is no standard protocol for the selection of joints to anesthetize. It has been suggested that the joints with maximal tenderness during palpation can be marked and identified under fluoroscopic inspection. Alternatively, in patients with unilateral lumbosacral pain, the L4–5 and L5–S1 joints can be investigated. If more isolated posterior element arthrosis is observed radiographically, a single joint can be studied. In patients with bilateral lumbosacral pain, these joints can be bilaterally addressed in a diagnostic fashion. If the diagnostic response from the L4–5 and L5–S1 injections is negative and a midlumbar pain complaint is reported, the L2–3 and L3–4 joints can then be studied in a similar coupled and unilateral or bilateral fashion. If the patient presents with midlumbar rather than lumbosacral pain, the L2–3 and L3–4 joints might be studied first. In the author’s practice, while a radiographic correlate to Z-joint pain has yet to be defined, MRI or CT scan evidence of more advanced arthrosis is also considered in selecting joints for further study when these imaging findings correspond to the patient’s pain location. Following a positive diagnostic response, therapeutic intra-articular injections could follow.

Similar to the treatment of SIJS, the therapeutic response arising from intra-articular injection with corticosteroid has not been more definitively revealed by controlled studies, and an inflammatory injury component has only been theorized. While intra-articular effusions can be observed on MRI, histologic studies have not revealed inflammatory cells in patients with spondylotic joints.61 Similarly, clinical studies have yet to identify a therapeutic effect from intra-articular injections in patients with inflammatory rheumatologic spinal conditions.61 A randomized, controlled study investigating the therapeutic benefits of intra-articular methylprednisolone, utilizing an initial single diagnostic injection screen and an intra-articular saline control, have suggested up to 46% of patients can realize significant pain relief at 6 months’ follow-up.76 Open and uncontrolled studies of fluoroscopically guided intra-articular injections suggest an 18–63% therapeutic effect for more than 6 months following injection.61,77–80 Pain relief realized following intra-articular injection might provide a window of opportunity to progress the patient in a spine rehabilitation program and graduate mechanical and manual therapies. If the patient failed to realize relief following therapeutic intra-articular injections or spondylotic anatomy prevented the performance of a diagnostic intra-articular injection, a diagnostic medial branch block81 could be utilized to confirm a diagnosis of Z-joint-mediated pain.

In the setting of a positive response to medial branch block, radiofrequency neurotomy can be considered. In the patient who initially demonstrated a positive response to an intra-articular injection, the medial branch block can serve as a confirmatory diagnostic measure. For patients in whom a diagnostic intra-articular injection was not previously performed, a positive response to medial branch block should be confirmed with an additional diagnostic screen to address the estimated 38% false-positive response rate with single uncontrolled blocks.74 A second and confirmatory medial branch block can be performed with a local anesthetic of different duration of action. In this scenario, the patient’s analgesic response with each test should correlate with the duration of action of the anesthetic utilized. Alternatively, the confirmatory injection can be performed with an informed patient in a blind fashion with either a saline placebo or anesthetic injected and the patient monitored for an appropriate response. The difficulty with employing local anesthetics of different duration is that the patient is required to accurately record and communicate their pain response over a period of hours which extends beyond the time spent in the office of the evaluating team. Additional response interpretation difficulties can arise in the patient who describes marked symptomatic relief after the injection of the longer-acting anesthetic, but whose response does not last for as long as one would predict based upon the agent’s half-life. To avoid these confounding factors, only shorter-acting anesthetics can be utilized and the response assessed in the office setting by an independent observer.

Patients who demonstrate a positive response to either variant of this double diagnostic screen can then be considered for medial branch radiofrequency denervation. While radiofrequency denervation represents a minimally invasive approach to the patient with chronic posterior element pain and localization of the innervating medial branches appears to be reliable, outcome studies are limited. Modest therapeutic responses have been described, uncontrolled small patient populations have been studied,82 and such procedures likely need to be repeated to offer sustained relief as reinervation to the painful joints can occur. A double-blind, controlled study of radiofrequency denervation versus sham lesions which employed a single diagnostic injection screen revealed only a two-point reduction in visual analog pain scores with the minority of patients realizing complete relief.83 A meticulously designed but small and uncontrolled study of medial branch neurotomy, which included electromyographic assessment of the paraspinal musculature to confirm denervation, demonstrated pronounced relief in 60% (n=9 of 460 initially screened) of patients at 12 month follow-up evaluation.82 If the denervation procedure proves helpful but the symptomatic response wanes, neurotomy can be repeated. A significant response should first be realized for at least 6–12 months.82

For those individuals with persistent axial pain of Z-joint origin which fails to improve despite the aforementioned therapies, surgical intervention in the form of posterolateral fusion should be considered only with great caution. While studies have yet to address the success of this approach in patients with Z-joint pain confirmed with a double diagnostic screen, the available literature does not suggest a correlation between posterior element pain and successful outcomes following fusion.84–86 While it may be tempting to assume that posterior element pain can be relieved by fusion, this has yet to be demonstrated. The potential remains for the fused joint to serve as an ongoing pain generator, as its painful tissue components remain after a typical posterior fusion approach. The possibility also remains that forces continue to be borne, albeit reduced, by the painful posterior elements following posterior stabilization. Finally, as mentioned in the discussion of SIJS, for any patient considered for fusion for Z-joint pain, preoperative lumbar discography, which will be further addressed in the next section of this chapter, should also be considered to rule out a contributing discogenic pain source. Discography also allows the clinician to better evaluate the anatomy and symptom response from adjacent levels. While a positive response to a double diagnostic screen would appear confirmatory for a primary Z-joint pain generator in these chronic cases, the possibility remains, potentially in a minority, that a concordant pain response will similarly be demonstrated during discography.87

INTERVERTEBRAL DISC

While the sacroiliac joint and Z-joints are suspected as primary pain generators in a significant but relative minority of patients with persistent axial lumbosacral pain, the intervertebral disc has stood center stage as the most commonly suspected pain generator in patients with both debilitating chronic and more acute axial pain. Mixter and Barr’s 1934 publication described herniated lumbar discs and their relationship to nerve root compressive syndromes.3 In addition to inducing radicular complaints affecting the lower limb, the degenerative disc is also believed to be a common primary pain generator in patients with axial pain. In a study of 92 consecutive patients presenting with chronic lumbar pain, provocative discography revealed a concordant pain response in 39%, most commonly at L4–5 and L5–S1.88 In a unique study utilizing progressive local anesthesia and selective tissue stimulation intraoperatively, Kuslich et al. demonstrated that while stimulation of the nerve root typically resulted in buttock and lower limb pain, stimulation of the disc, and in particular the anulus, most commonly resulted in a reproduction of the patient’s lumbar pain in a concordant fashion.60

The innervation of the intervertebral disc has been well defined. Abundant nerve endings with a variety of free and complex terminals have been identified in the outer third to half of the anulus fibrosus.89–91 The posterior plexus of nerves responsible for innervating the posterior anulus and posterior longitudinal ligament (PLL) is derived predominantly from the sinuvertebral nerve. The sinuvertebral nerve arises from both the somatic ventral ramus and autonomic gray ramus communicans and also supplies innervation to the ventral dura mater.92 Discitis represents a well-documented and painful condition arising from intervertebral disc infection.93,94 A noninfectious and degenerative condition labeled internal disc disruption describes a painful condition of the intervertebral disc involving a deterioration of the disc’s internal architecture with a relative maintenance of external contour. This mechanical breakdown leads to painful radial fissures which reach the outer third of the anulus fibrosus.95,96 Painful tears in the anulus are also presumed to arise, in the more acute injury setting and independent of a more gradual degenerative cascade, from flexion–rotation-type injuries.92 While abnormalities of the anulus are often not readily identified by conventional imaging techniques, discography and postdiscography CT can reveal abnormal disc architecture and painful annular tears.

Advanced imaging of the lumbar spine in patients with suspected discogenic pain typically does not provide confirmatory diagnostic information. Degenerative discs can be observed in 35% of asymptomatic 20–39 year olds, and 36% of individuals older than 60 years of age will demonstrate MRI evidence of disc herniation.97 With such a high incidence of abnormal findings in patients without axial pain, the observation of degenerative discs on MRI is clearly not diagnostic in isolation. Posterior annular tears, also referred to as high intensity zone (HIZ) lesions, are more commonly observed in patients with lumbar pain but can also be observed in up to 24% of asymptomatics.98 When appreciated in symptomatic patients, those discs with HIZ lesions have been observed to be twice as likely to produce a concordant pain response during discography when compared to discs without such lesions. Lumbar MRI findings might be most telling when disc space height and hydration are observed to be well preserved. Discs with a preservation of morphology have been demonstrated to be considerably less likely to be painful.96,99,100

Patients with discogenic pain can describe unilateral or bilateral axial pain with or without symptom referral to the proximal and distal lower limb.88 In a study of patients with discogenic pain confirmed by lumbar discography, historical findings were not shown to demonstrate statistical significance in predicting a discogenic pain source.88 Patients were equally as likely to describe increased pain with sitting as with standing. Additionally, physical examination findings, including increased pain with forward flexion, did not demonstrate statistical significance to predict a discogenic pain source. In assessing patients for possible discogenic pain, the clinician might consider the findings from two previous studies examining intradiscal pressures in healthy subjects assuming various postures.101,102 If the compromised and well-innervated posterior anulus is presumed to be the primary pain generator in patients with discogenic pain those positions or activities which maximize intradiscal pressure may be most likely to lead to annular stress and activation of nociceptive fibers. In these studies, erect sitting has been demonstrated to increase intradiscal pressure only slightly more than erect standing. Standing in a forward-flexed posture significantly increases intradiscal pressure and to a greater extent than sitting in a forward-slouched fashion. Reclining while seated reduces intradiscal pressure to a considerable extent, but pressure reductions are not as great as those observed while resting supine. The greatest intradiscal pressures are observed while performing lifting maneuvers in a standing and forward-flexed posture. Valsalva maneuver has been demonstrated to increase intradiscal pressure at least as much as sitting in a forward-flexed fashion. Disc pressures are also noted to more than double during evening hours, presumably secondary to bodily fluid shifts which can lead to a more-pressurized disc during morning hours. While statistical significance has not been demonstrated for particular historical findings or physical examination maneuvers, the studies of dynamic disc pressures likely offer clues in identifying patients with discogenic pain.

In the author’s experience, while Z-joint pain is more likely to be observed in older patients, discogenic pain can present in patients of all ages but is particularly common in the younger patient population, i.e. 18–65 years of age. Patients might describe an initial symptomatic onset following a defined and more stressful lifting or rotational maneuver. The gardening and snow shoveling seasons are particularly common times for patients to present with acute discogenic pain following a defined stressful maneuver, but often the onset of pain is more gradual and incremental. The discomfort is described as a deep-seated ache which is at times profound, forcing the patient to unload the spine and assume a supine position. Coughing and sneezing are often described as provocative and in some cases represent the initial inciting event. Patients realize increased pain with sitting, particularly during car travel or while at work or in a theater, and experience relief while resting supine with the lower extremities elevated. Standing and walking are often not as provocative, and bending and lifting maneuvers are typically avoided. Young parents and grandparents often present with axial pain of suspected discogenic origin, presumably secondary to the repetitive lifting and rotational maneuvers performed while caring for their children. Morning hours can be particularly problematic, likely secondary to increased intradiscal pressures following sleep and a prolonged period of recumbency, with a symptomatic decline after a period of ambulation and increased activity. At times, patients will describe a truncal shift, characterized by the torso being visibly and horizontally displaced relative to the pelvis, during symptomatic exacerbations. This antalgic posture is presumed to arise from asymmetric reactive paraspinal contraction and deeper-seated protective mechanisms arising from the activation of nociceptive fibers within a richly innervated and activated discogenic pain generator.103 Pain referral patterns to the lower limbs is also often reported, with such complaints described as poorly localizable, migratory, and less debilitating than the axial pain component. Some patients will even report a distal complaint of burning in the soles of the feet which coincides with worsening lumbar pain during prolonged sitting postures.

For a primary mechanical and discogenic pain generator to remain suspect, the physical examination should not reveal neurologic deficits consistent with radiculopathy. While sitting, the patient is often observed to lean rearward upon the elbows in an effort to reduce the more pain-provoking axial load to the spine. With the patient supine, passive pelvic rocking, during which the examiner maneuvers the patient’s lower limbs while passively flexed at the hips and knees, may prove provocative through the introduction of a torsional load to the intervertebral discs and a painful posterior anulus. Sustained hip flexion maneuvers, during which the patient actively flexes the hips while supine with the knees extended, is also often provocative. The response to this maneuver is often most notable as the limbs are allowed to slowly descend toward the exam table surface, presumably by simulating a valsalva-type maneuver with a resultant increase in intra-abdominal pressures. Sustained hip flexion or pelvic rocking may be more likely to be positive when the painful segment is at the L4–5 and/or L5–S1 levels, and may be less reliable for more cephalad segments. Pain is often reproduced with pressure applied over the lower lumbar spinous processes. In the author’s experience, standing with active forward flexion at waist with the knees extended most often reproduces axial pain in a concordant fashion. At times, transitioning from the flexed to neutral posture is the most pain-provoking maneuver. While standing extension is classically believed to be relieving, and is often observed to be so clinically, some patients will describe similar if not more intense pain during active extension maneuvers. A McKenzie approach to patient assessment has also been demonstrated to be fairly reliable in detecting pain of discogenic origin.104 Through such mechanical assessment, patients who realize symptom centralization or peripheralization following repetitive movements have been demonstrated to be more likely to demonstrate a symptomatic disc during lumbar discography.

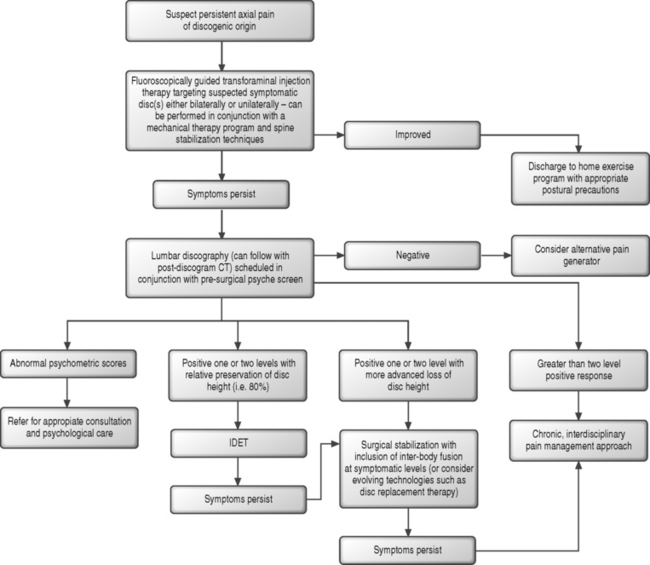

For those patients with persistent lumbosacral axial pain of suspected discogenic origin, an algorithmic approach (Fig. 89.4) can be initiated and epidural corticosteroid injections trialed. A plethora of literature, which will be more completely detailed in the appropriate chapters of this text, has described the role of transforaminal epidural injections in patients with radicular syndromes. Many uncontrolled studies,105–108 and more recently a meticulously designed randomized, prospective double-blind, controlled study1 have demonstrated the successful treatment of radiculopathy with transforaminal injection therapy. Transforaminal injections performed with fluoroscopic guidance allow for the most reliable means of administering corticosteroid to the ventral epidural space where the posterior anulus, PLL, spinal nerve, and ventral dura mater reside.109 Corticosteroids are believed to offer relief in patients with radicular syndromes by addressing the biochemical and inflammatory component of radiculopathy which has been extensively described in the literature and which will be more completely detailed in the chapters of this text addressing the pathophysiology of nerve root injury.110,111 The utilization of epidural corticosteroids in the treatment of axial lumbosacral pain, without a radicular component, is more speculative as the biochemical and inflammatory component of discogenic pain has yet to be as convincingly demonstrated.92 The pain generating processes at play in the patient with axial discogenic pain may arise from a prevailing mechanical insufficiency.112,113 Clinical studies investigating the role of epidural steroid injections have suggested but not clearly demonstrated success in the treatment of primary axial pain.114–116 The transforaminal injection approach offers the most direct means reaching the posterior anulus. Unlike the treatment of an inflamed spinal nerve where circumferential bathing of the target can be achieved, the possibility remains that the pain-generating fibers of the degenerative disc are not in direct contact with the epidural space. Alternatively, one might theorize that in the setting of a painful and incompetent anulus a component of the pain-generating process arises from the spillage of inflammatory mediators. This could lead to irritation of ventral spinal tissues such as the dura and PLL which are in intimate contact with the affected disc and are more accessible by transforaminal injection. In this author’s practice, due to concerns of iatrogenic discitis, an inability to isolate the painful disc without more interventional diagnostic measures, and a lack of supportive literature,117,118 intradiscal steroids are not offered in the treatment algorithm for discogenic pain.

In the patient with a suspected discogenic pain source who presents with central or bilateral lumbosacral symptoms and an MRI which reveals multilevel, i.e. L3–4 through L5–S1, degenerative disc disease, a bilateral S1 transforaminal injection is performed. This approach is offered in an effort to achieve a multilevel disc bathing effect through a cephalad push of injectate. If isolated degenerative change or a central contained protrusion with an annular tear is noted at L4–5 and disc morphology is preserved at L5–S1, a bilateral L5 transforaminal injection can be performed in an effort to maximally target the L4–5 disc. When targeting a particular disc in a unilateral or bilateral fashion, the foramen of the next caudal disc space is utilized for entry, as medication tends to spread in a cephalad fashion. No more than two injections are performed during a single procedural visit. In the patient with unilateral pain and two-level disc disease, i.e. L4–5 and L5–S1, an ipsilateral S1 and L5 injection approach is performed. Injection therapy can be offered in conjunction with a diagnosis-specific physical therapy program coordinated by a skilled therapist. In the author’s practice, success has been realized when such therapy is directed by a McKenzie certified or experienced mechanical therapist. The rehabilitation regimen should emphasize postural training, truncal strengthening, work ergonomics, and patient education, rather than promote a more passive and modality-based approach.119

For the patient with persistent and debilitating axial pain following an injection trial, lumbar discography and postdiscography CT imaging can be considered. The discogenic pain algorithm varies in this regard, as more-definitive diagnostic measures are deferred until initial treatments fail. We proceed in this fashion, as the majority of patients will ultimately not require discography, which is a more invasive approach than the injections previously described. A few important highlights regarding discography are warranted, as the chapters by Richard Derby and Mike Furman cover the topic in superb detail. A commonly referenced 1968 study by Holt120 raised concerns as a 37% false-positive provocative discography rate was demonstrated, and discography was labeled an unreliable diagnostic tool. This early investigation has been challenged on several fronts, and a 1990 study by Walsh et al.121 demonstrated a concordant pain response in 40% of discs studied in a small symptomatic group and a 0% false-positive rate in asymptomatic subjects. Discography remains an imperfect diagnostic tool, and subsequent studies have similarly revealed the potential for a false-positive response and in particular in patients with abnormal psychological profiles.98,122 Despite these shortcomings, discography represents an important diagnostic tool in the algorithmic approach to the patient with persistent axial pain and offers the only current means of identifying symptomatic discs. Provocative discography can be followed by CT imaging to reveal the nuclear morphology of the disc in the axial plane and further characterize the annular tears observed under fluoroscopy. Without discography, the treating clinician attempting to identify the symptomatic intervertebral disc(s) would need to rely solely upon MRI or CT imaging, which previous studies have convincingly demonstrated to be fraught with a high false-positive rate. Using an aggressive technique such as discography is essential at this point in the treatment algorithm, as the subsequent therapeutic options to be considered are among the most invasive, expensive, and controversial offered in spine care.

It is the patient with discogenic pain demonstrated by discography who epitomizes the challenges before the treating spine clinician. In this more commonly encountered group of patients with chronic and persistently debilitating discogenic pain, the likelihood of successful treatment outcomes becomes quite variable. Further interventions for the patient with discogenic pain should be reserved for those with ideally one and no more than two-level disc disease.123–126 In the author’s practice, patients with greater than two-level disease are not considered appropriate candidates for further intradiscal or surgical therapies. These individuals are directed toward a chronic and interdisciplinary pain modulation approach. In conjunction with lumbar discography and prior to further interventions, and in particular in those patients for whom surgical approaches are being considered, psychological factors must be critically assessed through the use of a screening examination. Patients with abnormal psychological profiles are more likely to demonstrate false-positive findings during provocative discography, and contributing psychosocial stressors can ultimately correlate with treatment failure and ongoing disability.122,127–130 Patients with persistent pain and abnormal psychological profiles can be referred for psychological care as a component of an interdisciplinary pain management program.

For those patients with one- or two-level positive discograms, intradiscal electrothermal (IDET) annuloplasty might be considered, but recent literature is now suggesting a therapeutic effect quite inferior to that initially suggested by uncontrolled trials. The potential mechanism of action of IDET remains unclear. Pain relief has been speculated to result from a coagulation of nociceptive fibers within the anulus,131,132 sealing of painful annular tears,132 collagen modulation and stiffening,131 or even a disruption of the chemical inflammatory cascade.132 A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of IDET126 has demonstrated no appreciable benefit in 50% of patients treated. Approximately 38% of patients in the treatment group realized greater that 50% pain relief, and 22% demonstrated 75% or greater reduction in pain. While the treatment group demonstrated a statistically significant overall 2.4 point drop (versus 1.1 in the control group) in the visual analog scale (4.2 at 6 months post treatment versus 6.6 at baseline), the clinical significance of this pain reduction remains less clear. The IDET group demonstrated better pain relief and Oswestry Disability Scores than the control group, but improvements in the Bodily Pain and Physical Functioning scores of the SF-36 were similar. These modest results were realized in a highly select patient population. Patients were screened for depression, had no prior spine surgery, had no workers compensation claim or injury litigation issues, and demonstrated no greater than 20% loss of disc space height at the treated levels. A second randomized, controlled trial,133 which studied patients with a greater baseline disability level and included workers compensation cases, demonstrated no clinically significant improvements in the treatment group. Scores from multiple outcome instruments were assessed at 6 month follow-up, and no patient was observed to realize what the authors defined as a successful clinical outcome.

In those patients with single- or, at most, two-level, disc disease who fail to realize relief from IDET or who are considered poor candidates, i.e. more-advanced loss of disc space height, surgical intervention in the form of fusion can be considered. Uncontrolled outcome studies investigating lumbar fusion procedures have described varying success rates ranging of 39–93%.125,134,135 In a study of posterolateral fusion in patients with positive preoperative discography, an overall 39% good or excellent outcome was observed.125 Of the 23 patients studied, 10 were workers compensation cases, and 90% of these proved to be treatment failures. Additionally, patients out of work for more than 3 months preoperatively demonstrated poor outcomes. A study of 137 patients123 in whom discography revealed abnormal disc morphology and symptom reproduction revealed an 89% clinical success rate following either anterior or posterolateral fusion. This compared favorably to the 52% clinical success rate in patients whose radiographs revealed disc degeneration with negative preoperative discograms. A 10-year follow-up study128 of anterior fusion patients demonstrated significant or complete pain relief in 78%. A retrospective study of four fusion techniques136 suggests that anterior interbody fusion performed in conjunction with posterior fusion and instrumentation results in superior outcomes to both stand-alone anterior interbody fusion and posterolateral fusion with instrumentation. A study investigating the potential role of preoperative pressure-controlled discography in surgical planning137 demonstrated no significant difference in outcomes in patients following either anterior, posterior, or combined surgical approaches. Patients with highly sensitive discs demonstrated superior outcomes following surgical approaches which included anterior interbody fusion when compared to an isolated posterolateral fusion approach. Studies demonstrating superior outcomes following anterior interbody fusion may be consistent with either superior segmental immobilization following anterior surgery138–142 or a greater likelihood of symptom resolution only following resection of the painful intervertebral disc.143,144

At this time, the treatment algorithm ends at surgical fusion. For those patients who choose not to proceed with surgery or for whom such intervention is inappropriate, i.e. three-level disc disease or a medical history which presents too great a surgical risk, a chronic pain modulation approach can be introduced. Patients considering surgical intervention for discogenic pain should also be educated in the areas of evolving treatments and technologies for the treatment of discogenic pain. These approaches are described in greater detail in dedicated chapters within this text and include intervertebral disc replacement,145 disc nucleus replacement,146,147 disc regenerative therapies,148 and perhaps, if such technology should evolve, percutaneous fusion utilizing the introduction of bone growth factors. Ultimately, well-designed and controlled prospective studies should demonstrate the superiority of these treatments to current fusion techniques in terms of clinical success, invasiveness, complications, and cost for spine clinicians to embrace such technology. As there are many exciting avenues of research in the treatment of discogenic pain, this information, along with available outcome data for current treatments, needs to be shared with patients so that they can remain educated and primary decision-makers in the algorithmic approach.

EXAMPLE CASES

Finally, before proceeding with the cases, a word about a less malignant, but commonly encountered clinical syndrome which needs to be considered when evaluating the patient with ongoing axial pain. Radicular syndromes must always remain in the differential when evaluating the patient with axial pain. Not all lumbosacral radiculopathies present with classic myotomal strength deficits or dermatomal pain distributions.149 While a consideration of radiculopathy is likely less important in the patient with isolated and central lumbar pain, the patient with lumbar pain radiating the buttock, inguinal region, or proximal limb may in fact be presenting with a less pronounced radicular syndrome. These pain distributions can be quite similar to the symptom referral patterns described for the three primary pain generators above. This possible symptom overlap emphasizes the need to perform a detailed history and physical examination. The revelation of a prior component of more distal pain radiation or weakness might provide valuable clues and elucidate a previously more overt radiculopathy. The examination should include a methodical neurologic examination in which bilateral sensation, strength, and reflexes are assessed for symmetry. If suspicion remains high, the examination and history unrevealing, and an isolated compressive lesion is appreciated on advanced imaging, additional diagnostic tools can be employed. Electrodiagnostic studies and diagnostic selective nerve root injections, which will be addressed in dedicated chapters of this text, can be included in the diagnostic algorithm in an effort to more definitively rule out a symptomatic nerve root. In the patient with radiographic evidence of an isolated compressive injury, i.e. posterolateral protrusion to the right at L4–5 with compression of the L5 root, lumbar and buttock pain on the right, and a history and exam not further suggestive of radiculopathy, the differential needs to be expanded. The patient may be experiencing symptoms arising from a symptomatic nerve root, a primary discogenic pain source, or even pain arising from combined pain generators which include an inflamed nerve root dura and dorsal root ganglion without associated or more overt neural dysfunction. The addition of these diagnostic tools might help to further clarify such a patient’s candidacy for introduction into the axial pain generator algorithms.

Case 1

The patient then decided to proceed with further physical therapy with an experienced mechanical therapist and realized some additional relief after 3 weeks of treatment and the introduction of a home exercise regimen. Five months after her initial injury, describing an overall 75% improvement, but with residual lumbar discomfort which prohibited her from lifting or sitting for extended periods without pain, she requested further information regarding her treatment options. The role of lumbar discography was reviewed as a potential precursor to intradiscal annuloplasty, fusion, or, at some point in time, evolving techniques such as disc replacement therapy. The pertinent literature and range of therapeutic outcomes was referenced in our discussion. We also reviewed the option of living with her discomfort along with activity and postural modifications or trialing a more chronic pain management approach and medication trials. She decided to proceed with discography from L3–4 through L5–S1. A concordant pain response was elicited at L4–5 where an annular tear was observed without resultant pain or annular disruption at the adjacent control discs. She then wished to proceed with IDET. After her procedure and 6 weeks of graduating activity and the tapering use of an external orthosis, only mild additional relief was described, with the patient then reporting an overall 80% improvement. While her pain was as easily provoked through similar activities, her localized lumbar discomfort was not as sharp in nature. She chose to continue her home program, addressed her seating system and work station, and continued the intermittent use of nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents. She decided that she would rather live with her current level of discomfort than pursue further interventions. The patient revealed that she was satisfied with the pain relief obtained and was pleased with her decision to undergo the IDET procedure considering the outcome realised.

1 Riew KD, Yin Y, Gilula L, et al. The effect of nerve root injections on the need for operative treatment of lumbar radicular pain. A prospective, randomized, controlled, double blind study. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 2000;82(11):1589-1593.

2 Manchikanti L. Role of neuraxial steroids in interventional pain management. Pain Phys. 2002;5(2):182-199.

3 Mixter WJ, Barr JS. Rupture of the intervertebral disc with involvement of the spinal canal. N Engl J Med. 1934;211:210.

4 Bogduk N. Low back pain. In: Bogduk N, editor. Clinical anatomy of the lumbar spine and sacrum. 3rd edn. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997:199-200.

5 Albee S. The study of the anatomy and the clinical importance of the sacroiliac joint. JAMA. 1909;16:1273-1276.

6 Alderink GJ. The sacroiliac joint; review of anatomy, mechanics, and function. Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1991;13:71-84.

7 Wilkinson M, Bywaters EGL. Clinical features and courses of ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis. 1958;17:209-228.

8 Dunn EJ, Bryan DM, Nugent JT, et al. Pyogenic infections of the sacroiliac joint. Clin Orthop. 1976;118:113-117.

9 Bernard TN, Cassidy JD. The sacroiliac joint syndrome: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management. In: Frymoyer JW, editor. The adult spine: principles and practice. New York: Raven Press; 1991:2107-2130.

10 Fortin JD. Sacroiliac joint dysfunction. A new prospective. J Back Musculoskel Rehabil. 1993;3:31-43.

11 Humphrey SM, Inman RD. Metastatic adenocarcinoma mimicking unilateral sacroiliitis. J Rheum. 1995;22:970-972.

12 Fortin JD, Dwyer AP, West S, et al. Sacroiliac joint: pain referral maps upon applying a new injection/arthrography technique. Part I: asymptomatic volunteers. Spine. 1994;19:1475-1482.

13 Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Bogduk N. The sacroiliac joint in chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995;20:31-37.

14 Maigne J, Aivalikilis A, Pfefer F. Results of sacroiliac joint double block and value of sacroiliac pain provocation tests in 54 patients with low back pain. Spine. 1996;21:1889-1892.

15 Egund N, Olsson TH, Schmid H, et al. Movements in the sacroiliac joint demonstrated with roentgen stereophotogrammetry. Acta Radiologica Diagnosis. 1978;19:833-846.

16 Sturesson B, Selvik G, Uden A. Movements of the sacroiliac joints. A roentgen stereo photogrammetric analysis. Spine. 1989;14:162-165.

17 Slipman CW, Sterenfeld EB, Chou LH, et al. The value of radionuclide imaging in the diagnosis of sacroiliac joint syndrome. Spine. 1996;21:2251-2254.

18 Battafarano DF, West SG, Rak KM, et al. Comparison of bone scan, computed tomography, and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of active sacroiliitis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1993;23:161-176.

19 Hanly JG, Mitchell MJ, Barnes DC, et al. Early recognition of sacroiliitis by magnetic resonance imaging and single photon emission CT. J Rheumatol. 1994;21:2088-2095.

20 Russel AS, Lentle BC, Percy JS. Investigation of sacroiliac disease: comparative evaluation of radiological and radionuclide techniques. J Rheumatol. 1975;2:45-51.

21 Cohen AS, McNeill JM, Calkins E, et al. The normal sacroiliac joint. An analysis of 88 sacroiliac roentgenograms. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther. 1967;100:559-563.

22 Jajic I, Jajic Z. The prevalence of osteoarthritis of the sacroiliac joints in an urban population. Clin Rheumatol. 1987;6:39-41.

23 Vogel JBIII, Brown WH, Helms CA, et al. The normal sacroiliac joint: a CT study of asymptomatic patients. Radiology. 1984;151:433-437.

24 Moore M. Diagnosis and surgical treatment of chronic sacroiliac artrhopathy. In: Proceedings of the 7th annual meeting of the North American Spine Society. Boston: North American Spine Society; 1992:100.

25 Leblanc KE. Sacroiliac sprain: an overlooked cause of back pain. Am Fam Physician. 1992;46:1459-1463.

26 Norman G. Sacroiliac disease and its relationship to lower abdominal pain. Am J Surg. 1958;116:54-56.

27 Smith-Peterson MN. Clinical diagnosis of common sacroiliac joint conditions. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther. 1924;12:546-550.

28 Woodward JL, Weinstein SM. Epidural injections for the diagnosis and management of axial and radicular pain syndromes. Phys Med Rehab Clin N Am. Injection techniques – principles and practice. 1995;6:691-714.

29 Dreyfuss P, Michaelsen DC, Pauza K. The value of the medical history and physical examination in diagnosing sacroiliac joint pain. Spine. 1996;21:2594-2602.

30 Kirkaldy-Willis WH. A more precise diagnosis for low back pain. Spine. 1979;4:102-109.

31 Slipman CW, Jackson HP, Lipetz JS, et al. Sacroiliac joint pain referral zones. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81:334-338.

32 Carmichael JP. Inter- and intra-examiner reliability of palpation for sacroiliac joint dysfunction. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1987;10:164-171.

33 Potter N, Rothstein J. Intertester reliability for selected clinical tests of the sacroiliac joint. Phys Ther. 1981;11:1671-1675.

34 Deyfuss P, Dreyer S, Griffen J, et al. Positive sacroiliac screening tests in asymptomatic adults. Spine. 1994;19:1138-1143.

35 Slipman CW, Sterenfeld EB, Chou LH, et al. The predictive value of provocative sacroiliac joint stress maneuvers in the diagnosis of sacroiliac joint syndrome. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:288-292.

36 Laslett M, Young SB, Aprill CN, et al. Diagnosing painful sacroiliac joints: A validity study of a McKenzie evaluation and sacroiliac provocation tests. Austral J Physiother. 2003;49:89-97.

37 Dreyfuss P, Cole AJ, Pauza K. Sacroiliac joint injection techniques. Phys Med Rehab Clin N Am. Injection techniques principles and practice. 1995;6(4):785-814.

38 Haldeman K, Sotohall R. The diagnosis and treatment of sacroiliac conditions involving injection of procaine (Novacaine). J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1938;3:675-685.

39 Miskew DB, Block RA, Witt PF. Aspiration of infected sacro-iliac joints. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1979;61A:1071-1072.

40 Rosenberg JM, Quint TJ, deRosayro AM. Computerized tomographic localization of clinically-guided sacroiliac joint injections. Clin J Pain. 2000;16:18-21.

41 Norman G, May A. Sacroiliac conditions simulating intervertebral disc syndrome. Wes J Surg. 1956;64:461-462.

42 Slipman CW, Lipetz JS, Plastaras CT, et al. Fluoroscopically guided therapeutic sacroiliac joint injections for sacroiliac joint syndrome. Am Jour Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;80:425-432.

43 Maguars Y, Mathis C, Berthelot J-M, et al. Assessment of efficacy of sacroiliac joint corticosteroid injections in spondyloarthropathies: a double blind study. Br J Rheumatol. 1996;35:767-770.

44 Maguars Y, Mathis C, Vilon P, et al. Corticosteroid injection of the sacroiliac joint in patients with seronegative spondyloarthropathy. Arthritis Rheum. 1992;35:564-568.

45 Flower RJ, Blackwell GJ. Anti-inflammatory steroids induce biosynthesis of phospholipase A2 inhibitor which prevents prostaglandin generation. Nature. 1979;278:456-459.

46 Willard FH, Carreiro JE, Manko W. The long posterior interosseous ligament and the sacrococcygeal plexus. In: Proceedings of the Third Interdisciplinary World Congress of Low Back and Pelvic Pain. Vienna: 1998.

47 Dreyfuss P, Akuthota V, Willard F, et al. Are lateral branch blocks of the S1–3 dorsal rami reasonably target specific? In: Proceedings of ISIS 8th Annual Scientific Meeting. San Francisco; 2000:25–30.

48 Yin W, Willard F, Carreiro J, et al. Sensory stimulation-guided sacroiliac joint radiofrequency neurotomy: Technique based on neuroanatomy of the dorsal sacral plexus. Spine. 2003;28:2419-2425.

49 Dreyfuss P, Park K, Bogduk N. Do L5 dorsal ramus and S1–4 lateral branch blocks protect the sacroiliac joint from an experimental pain stimulus? A randomized, double-blinded controlled study. In: Proceedings of ISIS 8th Annual Scientific Meeting. San Francisco; 2000:31–36.

50 Gevargez A, Groenemeyer D, Schirp S, et al. CT-guided percutaneous radio-frequency denervation of the sacroiliac joint. Eur Radiol. 2002:121360-121365.

51 Cohen SP, Abdi S. Lateral branch blocks as a treatment for sacroiliac joint pain: A pilot study. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003;28:113-119.

52 Ferrante FM, King LF, Roche EA, et al. Radiofrequency sacroiliac joint denervation for sacroiliac joint syndrome. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2001;26:137-142.

53 Berthelot JM, Gouin F, Glemarec J, et al. Possible uses of arthrodesis for intractable sacroiliitis in spondyloarthropathy. Report of two cases. Spine. 2002;26:2297-2299.

54 Goldthwait JE. The lumbosacral articulation: An explanation of many cases of lumbago, sciatica, and paraplegia. Boston Med Surg J. 1911;164:365-372.

55 Glover JR. Arthrography of the joints of the lumbar vertebral arches. Orthop Clin North Am. 1977;8:37-42.

56 Lewin T, Moffit B, Viidik A. The morphology of the lumbar synovial intervertebral joints. Acta Morphologica Neurologica Scand. 1962;4:299-319.

57 Bogduk N. Back pain: Zygapophyseal blocks and epidural steroids. In: Cousins MJ, Bridenbaugh PO, editors. Neural blockade in clinical anesthesia and management of pain. 2nd edn. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1989:935-954.

58 Mooney V, Robertson J. Facet joint syndrome. Clin Orthop. 1976;115:149-156.

59 McCall IW, Park WM, O’Brien JP. Induced pain referral from posterior lumbar elements in normal subjects. Spine. 1979;4:441-446.

60 Kuslich SD, Ulstrom CL, Michael CJ. The tissue origin of low back pain and sciatica: A report of pain response to tissue stimulation during operations on the lumbar spine using local anesthesia. Orthop Clin North Am. 1993;22:181-187.

61 Dreyer SJ, Dreyfuss P, Cole AJ. Zygapophyseal (facet) joint injections. Intra-articular and medial branch block techniques. Phys Med Rehab Clin N Am. Injection techniques principles and practice. 1995;6(4):715-741.

62 Bough B, Thakore J, Davies M, et al. Degeneration of the lumbar facet joints. Arthrography and pathology. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1990;72:275-276.

63 Carrera GF. Lumbar facet joint injection in low back pain and sciatica: Preliminary results. Radiology. 1980;137:665-667.

64 Lewinnek GE, Warfield CA. Facet joint degeneration as a cause of low back pain. Clin Orthop. 1986;213:216-222.

65 Eisenstein SM, Parry CR. The lumbar facet arthrosis syndrome – clinical presentation and articular surface changes. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1987;69:3-7.

66 Twomey LT, Taylor JR, Taylor MM. Unsuspected damage to lumbar zygapophyseal (facet) joints after motor vehicle accidents. Med J Aust. 1989;151:210-217.

67 Campbell AJ, Wells IP. Pigmented villonodular synovitis of a lumbar vertebral facet joint. J Bone Joint Surg. 1982;64A:145-146.

68 Rush J, Griffiths J. Suppurative arthritis of a lumbar facet joint. J Bone Joint Surg. 1989;71B:161-162.

69 Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, et al. Clinical features of patients with pain stemming from the lumbar zygapophyseal joints. Is the lumbar facet syndrome a clinical entity. Spine. 1994;19:1132-1137.

70 Lawrence JS, Sharp J, Ball J, et al. Osteoarthritis. Prevalence in the population and relationship between symptoms and X-ray changes. Ann Rheum Dis. 1966;25:1-24.

71 Magora A, Schwartz TA. Relation between the low back pain syndrome and X-ray findings. Scan J Rehabil Med. 1976;8:115-125.

72 Schwarzer AC, Wang S, O’Driscoll D, et al. The ability of computed tomography to identify a painful zygapophyseal joint in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995;20:907-912.

73 Jackson RP, Jacobs RR, Montesano PX. Facet joint injection in low back pain: A prospective statistical study. Spine. 1988;13:966-971.

74 Schwarzer AC, Derby R, Aprill CN, et al. The false positive rate of single lumbar zygapophyseal joint blocks. Pain. 1994;58:195-200.

75 Revel ME, Listrat VM, Chevalier XJ, et al. Facet joint block for low back pain: Identifying predictors of a good response. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1992;73:824-828.

76 Carette S, Marcoux S, Truchon R, et al. A controlled trial of corticosteroid injections into the facet joints for chronic low back pain. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:1002-1007.

77 Carrera GF. Lumbar facet joint injection in low back pain and sciatica: Preliminary results. Radiology. 1980;137:665-667.

78 Destouet JM, Gilula LA, Murphy WA, et al. Lumbar facet joint injection: Indication, technique, clinical correlation and preliminary results. Radiology. 1982;145:321-325.

79 Lau LSW, Littlejohn GO, Miller MH. Clinical evaluation of intra-articular injections for lumbar facet joint pain. Med J Aust. 1985;143:563-565.

80 Murtagh FR. Computed tomography and fluoroscopy guided anaesthesia and steroid injection in facet syndrome. Spine. 1988;13:686-689.

81 Dreyfuss P, Schwarzer AC, Lau P, et al. Specificity of lumbar medial branch and L5 dorsal ramus blocks: a computed tomographic study. Spine. 1997;22:895-902.

82 Dreyfuss P, Halbrook B, Pauza K, et al. Efficacy and validity of radiofrequency neurotomy for chronic lumbar zygapophyseal joint pain. Spine. 2000;25:1270-1277.

83 Van Kleef M, Barendse G, Kessels A, et al. Randomized trial of radiofrequency lumbar facet denervation for chronic low back pain. Spine. 1999;24:1937-1942.

84 Esses SI, Moro JK. The value of facet blocks in patient selection for lumbar fusion. Spine. 1993;18:185-190.

85 Jackson RP. The facet syndrome: Myth or reality? Clin Orthop. 1992;279:110-121.

86 Tsang IK. Perspective on low back pain. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 1993;5:219-223.

87 Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, et al. The relative contributions of the disc and zygapophyseal joint in chronic low back pain. Spine. 1994;19:801-806.

88 Schwarzer AC, Aprill CN, Derby R, et al. The prevalence and clinical features of internal disc disruption syndrome in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine. 1995;20:1878-1883.

89 Malinsky J. The ontogenetic development of nerve terminations in the intervertebral discs of man. Acta Anat. 1959;38:96-113.

90 Rabischong P, Louis R, Vingard J, et al. The intervertebral disc. Anat Clin. 1978;1:55-64.

91 Yoshizawa H, O’Brien JP, Thomas-Smith W, et al. The neuropathology of intervertebral discs removed for low back pain. J Path. 1980;132:95-104.

92 Bogduk N. Clinical anatomy of the lumbar spine and sacrum, 3rd ed., New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1997:138-207.

93 Fraser RD, Osti OL, Vernon-Roberts B. Discitis after discography. J Bone Joint Surg. 1987;69B:26-35.

94 Guyer RD, Collier R, Stith WJ, et al. Discitis after discography. Spine. 1988;13:1352-1354.

95 Bogduk N. The lumbar disc and low back pain. Neurosurg Clin North Am. 1991;2:791-806.

96 Bogduk N, Aprill C, Derby R. White AH, editor. Spine care. Mosby, St Louis, 1995;219-238.

97 Boden SD, Davis DO, Dina TS, et al. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the lumbar spine in asymptomatic subjects. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1990;72:403-408.

98 Carragee EJ, Paragioudakis SJ, Khurana S. 2000 Volvo Award winner in clinical studies: Lumbar high-intensity zone and discography in subjects without low back problems. Spine. 2001;23:2987-2992.

99 Milette PC, Fontaine S, Lepanto L, et al. Differentiating lumbar disc protrusions, disc bulges, and discs with normal contour but abnormal signal intensity. Magnetic resonance imaging with discographic correlations. Spine. 1999;24:44-53.

100 Horton WC, Daftari TK. Which disc as visualized by magnetic resonance imaging is actually a source of pain. A correlation between magnetic resonance imaging and discography. Spine. 1992;17:S164-S171.

101 Nachemson A. The load on lumbar disks in different positions of the body. Clin Orthop. 1966;45:107-122.

102 Wilke HJ, Neef P, Caimi M. New in vivo measurements of pressures in the intervertebral disc in daily life. Spine. 1999;24:755-762.

103 Suk KS, Lee HM, Moon SH, et al. Lumbosacral scoliotic list by lumbar disc herniation. Spine. 2001;26:667-671.

104 Donelson R, Aprill C, Medcalf R, et al. A prospective study of centralization of lumbar and referred pain. A predictor of symptomatic discs and annular competence. Spine. 1997;22:1115-1122.

105 Weiner BK, Fraser RD. Foraminal injection for far lateral disc herniation. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1997;79:804-807.

106 Lutz GE, Vad VB, Wisneski RJ. Fluoroscopic transforaminal epidural steroids: an outcome study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:1362-1366.

107 Botwin KP, Gruber RD, Bouchlas CG, et al. Fluoroscopically guided lumbar transforaminal epidural steroid injections in degenerative lumbar stenosis: an outcome study. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;81:898-905.

108 Narozny M, Zanetti M, Boos N. Therapeutic efficacy of selective nerve root blocks in the treatment of radicular leg pain. Swiss Med Wkly. 2001;131:75-80.

109 Bogduk N, Cristophidis N, Cherry D, et al. Epidural steroids in the management of back pain and sciatica of spinal origin. Report of the Working Party on Epidural Use of Steroids in the Management of Back Pain. Canberra: Nation Health and Medical Research Council, 1993.

110 Lipetz JS. Pathophysiology of inflammatory, degenerative, and compressive radiculopathies. Phys Med Rehab Clin N Am. 2002;13:439-450.

111 Slipman CW, Chow DW. Therapeutic spinal corticosteroid injections for the management of radiculopathies. Phys Med Rehab Clin N Am. 2002;13:697-712.

112 Adams MA, McMillan DW, Green TP, et al. Sustained loading generates stress concentrations in lumbar intervertebral discs. Spine. 1996;21:434-438.

113 McNally DS, Shackleford IM, Goodship AE, et al. In vivo stress measurement can predict pain on discography. Spine. 1996;21:2580-2587.

114 White AH, Derby R, Wynne G. Epidural injections for the diagnosis and treatment of low back pain. Spine. 1980;5:78-82.

115 Rapp SE, Haselkorn JK, Elam K, et al. Epidural steroid injection in the treatment of low back pain: A meta-analysis. Anesthesiology. 1994;78:A923.

116 Weinstein SM, Herring SA, Derby R. Contemporary concepts in spine care. Epidural steroid injections. Spine. 1995;20:1842-1846.

117 Simmons JW, McMillin JN, Emery SF, et al. Intradiscal steroids. A prospective double-blind clinical trial. Spine. 1992;17:S172-S175.

118 Khot A, Bowditch M, Powell J, et al. The use of lumbar intradiscal steroid therapy for lumbar spinal discogenic pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2004;29:833-836.

119 Petersen T, Kryger P, Ekdahl C, et al. The effect of McKenzie therapy as compared with that of intensive strengthening and training for the treatment of patients with subacute or chronic low back pain: A randomized controlled trial. Spine. 2002;27:1702-1709.

120 Holt EP. The question of lumbar discography. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1968;50:720-726.

121 Walsh TR, Weinstein JN, Spratt KF, et al. Lumbar discography in normal subjects. J Bone Joint Surg [Am]. 1990;72:1081-1088.

122 Carragee EJ, Chen Y, Tanner CM, et al. Provocative discography in patients after limited lumbar discectomy: A controlled randomized study of pain response in symptomatic and asymptomatic subjects. Spine. 2001;25:3065-3071.

123 Colhoun E, McCall IW, Williams L, et al. Provocation discography as a guide to planning operations of the spine. J Bone Joint Surg [Br]. 1988;70:267-271.

124 Moore KR, Pinto MR, Butler LM. Degenerative disc disease treated with combined anterior and posterior arthrodesis and posterior instrumentation. Spine. 2002;27:1680-1686.

125 Parker LM, Murrell SE, Boden SD, et al. The outcome of posterolateral fusion in highly selected patients with discogenic low back pain. Spine. 1996;21:1909-1917.

126 Pauza KJ, Howell S, Dreyfuss P, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of intradiscal electrothermal therapy for the treatment of discogenic low back pain. Spine. 2004;4:27-35.

127 Block AR, Vanharanta H, Ohnmeiss DD, et al. Discographic pain report: Influence of psychological factors. Spine. 1996;21:334-338.

128 Penta M, Fraser RD. Anterior lumbar interbody fusion. A minimum 10-year follow up. Spine. 1997;22:2429-2434.

129 Greenough CG, Peterson MD, Hadlow S, et al. Instrumented posterolateral lumbar fusion. Results and comparison with anterior interbody fusion. Spine. 1998;23:479-486.

130 Trief PM, Grant W, Fredrickson B. A prospective study of psychological predictors of lumbar surgery outcome. Spine. 2000;25:2616-2621.

131 Saal JS, Saal JA. Management of chronic discogenic low back pain with a thermal intradiscal catheter. A preliminary report. Spine. 2000;25:382-388.

132 Karasek M, Bogduk N. Intradiscal electrothermal annuloplasty: percutaneous treatment of chronic discogenic low back pain. Techniques Reg Anesth Pain Manage. 2001;5:130-135.

133 Freeman BJC. A randomized controlled efficacy study: Intradiscal electrothermal therapy (IDET) versus placebo. Proceedings of the annual meeting of the International Society for the Study of the Lumbar Spine. Vancouver: 2003.

134 Bernard TNJr. Lumbar discography and post discography computerized tomography: Refining the diagnosis of low back pain. Spine. 1990;15:690-707.

135 Lee CK, Vessa P, Lee JK. Chronic disabling low back pain syndrome caused by internal disc derangements: The results of disc excision and posterior lumbar interbody fusion. Spine. 1995;20:356-361.

136 Vamvanij V, Fredrickson B, Thorpe JM, et al. Surgical treatment of internal disc disruption: An outcome study of four fusion techniques. J Spin Disord. 1998;11:375-382.

137 Derby R, et al. The ability of pressure-controlled discography to predict surgical and nonsurgical outcomes. Spine. 1999;24:364-371.

138 Lee CK, Langrana NA. Lumbosacral spinal fusion: A biomechanical study. Spine. 1984;9:574-581.

139 Rolander SD. Motion of the lumbar spine with special reference to stabilizing effect of posterior fusion. Acta Orthop Scand Suppl. 1966;90:1.

140 White AA, Panjabi MM. Clinical biomechanics of the spine: Biomechanical considerations in the surgical management of the spine, 2nd edn., Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1990:529-535.

141 Ylinen P, Kinnunen J, Laasonen EM, et al. Lumbar spine interbody fusion with reinforced hydroxyapatite implants. Arch Ortho Trauma Surg. 1991;110:250-256.

142 Zdeblick TA, Smith GR, Warden KE, et al. Two-point fixation of the lumbar spine. Differential stability in rotation. Spine. 1991;16(S):298-301.

143 Saal JS, Franson RC, Saal JA, et al. Human disc PGE2 is inflammatory. Proceedings of the Sixth Annual North American Spine Society Meeting. Colorado; 1991.

144 Weinstein J, Claverie W, Gibson S. The pain of discography. Spine. 1988;13:1344-1348.

145 Delamarter RB, Fribourg DM, Kanim LE, et al. ProDisc artificial total lumbar disc replacement: introduction and early results from the United States clinical trial. Spine. 2003;28:S167-S175.

146 Klara PM, Ray CD. Artificial nucleus replacement: clinical experience. Spine. 2002;27:1374-1377.

147 Sagi HC, Bao QB, Yuan HA. Nuclear replacement strategies. Ortho Clin North Am. 2003;34:263-267.

148 Kroeber MW, Unglaub F, Wang H, et al. New in vivo animal model to create intervertebral disc degeneration and to investigate the effects of therapeutic strategies to stimulate disc regeneration. Spine. 2002;27:2684-2690.

149 Nitta H, Tajima T, Sugiyama H, et al. Study of dermatomes by means of selective lumbar spinal nerve block. Spine. 1993;18:782-786.