Chapter 56 Lower Limb Peripheral Vascular Disease

Lower limb peripheral vascular disease includes arterial, venous, and lymphatic disorders (Box 56-1). Arterial disease in the lower limb can be caused by atherosclerosis, thrombosis, embolism, vasospasm, arterial dissection, or vasculitis. Venous disease in the lower limb includes venous stasis, deep venous thrombosis, thrombophlebitis, and venous insufficiency. Lymphatic disorders of the lower limb include primary and secondary lymphedema.

Arterial Disease of the Lower Limb

Lower Limb Arterial Anatomy

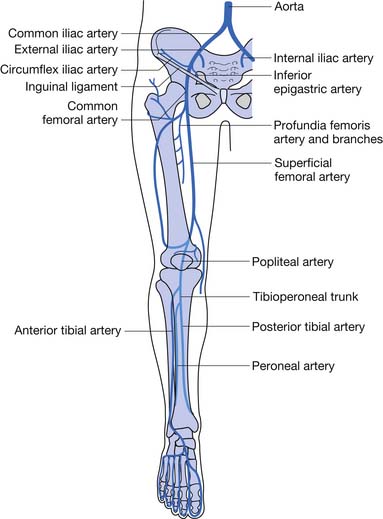

Knowledge of the lower limb arterial anatomy is necessary to better understand the disease process and improve patient assessment and management. The abdominal aorta divides into the two common iliac arteries at the level of the fourth lumbar vertebra. The common iliac arteries further divide into the internal and external iliac arteries. The external iliac artery passes under the inguinal ligament and then enters the thigh as the common femoral artery, which divides into the superficial and deep femoral arteries. When the superficial femoral artery reaches the level of the knee, it becomes the popliteal artery. The popliteal artery divides below the knee to become the anterior and posterior tibial arteries. The anterior tibial artery gives rise to the dorsalis pedis artery (Figure 56-1).

Atherosclerotic Peripheral Arterial Disease

Epidemiology and Risk Factors of Atherosclerotic Peripheral Arterial Disease

PAD is common in the United States, affecting around 8 million Americans.25 Men present to physicians more frequently. When screening is performed on asymptomatic individuals, however, women appear to be affected as commonly as men. Blacks are more affected than other races.41 Smoking is the biggest risk factor for PAD. Smokers are at higher risk for PAD, and they develop it at an earlier age than nonsmokers.51 Diabetes is also a major risk factor for PAD. The risk of PAD increases 26% for every 1% increase in hemoglobin A1c.58 Other factors associated with PAD include hypertension, dyslipidemia, chronic renal insufficiency, elevated inflammatory biomarkers, and hyperhomocysteinemia (Box 56-2).

Clinical Presentation of Atherosclerotic Peripheral Arterial Disease

The various clinical presentations of PAD include asymptomatic, intermittent claudication (IC), critical limb ischemia (CLI), and acute limb ischemia, with the most common being asymptomatic (Box 56-3). Only around 10% of people with PAD report symptoms of IC. Around half of PAD patients report leg symptoms other than claudication. Forty percent of people with PAD report no leg symptoms at all.25

BOX 56-3 Clinical Presentations of Peripheral Arterial Disease

Asymptomatic

The majority of PAD patients do not have the classic symptoms of IC. The absence of symptoms does not suggest a benign course. Complete occlusion of a major leg artery was found in one third of patients with asymptomatic PAD in one study.9 The lack of symptoms is due to low physical activity level rather than mild disease. Functional impairment can be present despite the lack of symptoms.30 Functional decline has been shown to be related to ankle–brachial index (ABI) even in the absence of symptoms.29

Intermittent Claudication

Classic IC is leg pain with exertion that is relieved with rest. Claudication produces ischemia in the affected muscle, which results in pain. Depending on the site of arterial disease, pain can be felt in the buttock, hip, thigh, calf, or foot. IC limits the patient’s ability to walk, which hinders community activities and exercise ability. Patients with claudication have decreased walking speed and distance, as well as decreased leg function. It has been reported that IC negatively affects physical functioning of patients more than arthritis, cancer, or chronic lung disease.6

Acute Limb Ischemia

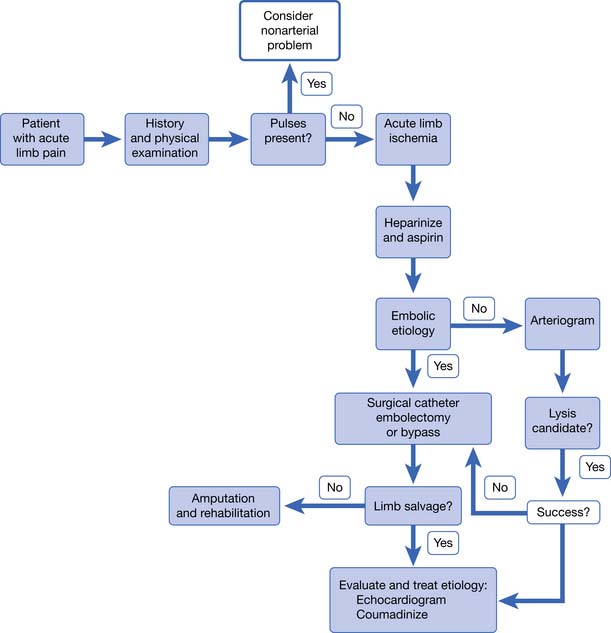

Acute arterial occlusion of the lower limb can be caused by thrombosis, embolism, or dissection (Figure 56-2). This is a limb-threatening medical emergency. The incidence is around 140 new cases per million persons per year.41 Patients present with pain, poikilothermia, and pulselessness. They might also have the classic symptoms of pallor, paresthesia, and paralysis. Symptoms are usually present for only hours to days when the patient presents. If symptoms have been present for less than 2 weeks, it is considered to be acute limb ischemia. Acute limb ischemia requires emergent vascular surgery evaluation and treatment. Just as with myocardial infarction and stroke, reperfusion must occur as soon as possible to prevent irreversible tissue loss (muscle, nerve, or limb loss). Embolectomy and thrombolysis can be attempted in appropriate patients. Up to 30 percent of patients with acute limb ischemia will require amputation in the first month of presentation.41

Critical Limb Ischemia

CLI is chronic ischemia (Figure 56-3). CLI is ischemia of the limb for more than 2 weeks causing rest pain, ischemic ulcers, and gangrene. Because so many patients with PAD are asymptomatic, it is not uncommon for the initial presentation of PAD to be CLI. The incidence is around 500 new cases per million persons per year.41

Evaluation of Atherosclerotic Peripheral Arterial Disease

History and Physical Examination

A low awareness of PAD is found in the general public and among physicians.14 This lack of awareness, and the fact that most PAD is asymptomatic, leads to underdiagnosis of PAD. Physicians must maintain a high level of suspicion when evaluating patients at risk. Making the diagnosis of PAD is important because it has prognostic significance for impairment of mobility and physical functioning, as well as morbidity and mortality.

On physical examination, lower limb pulses should be evaluated, including the dorsalis pedis, posterior tibial, popliteal, and femoral. The presence of pedal pulses has a 90% negative predictive value for the diagnosis of PAD.41 Absent or diminished pulses, however, do not always indicate the presence of PAD but should prompt further investigation. The legs and feet should be examined for changes of skin temperature, color, and evidence of poor vascular flow. Decreased arterial blood flow to the legs can cause muscle atrophy, thin shiny skin, and decreased hair growth. Nails are often thick and brittle. The foot can appear red or purple when in the dependent position (dependent rubor) and show pallor when elevated.

Vascular Testing for Peripheral Arterial Disease

Ankle–Brachial Index

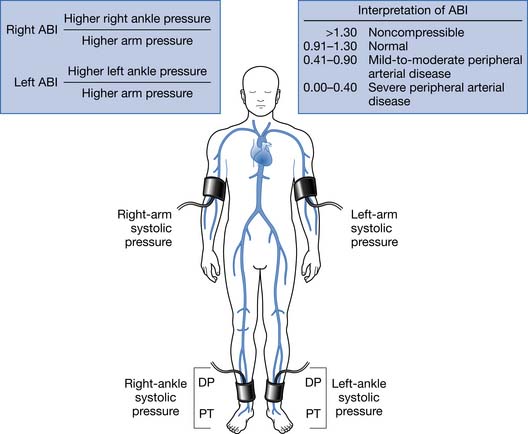

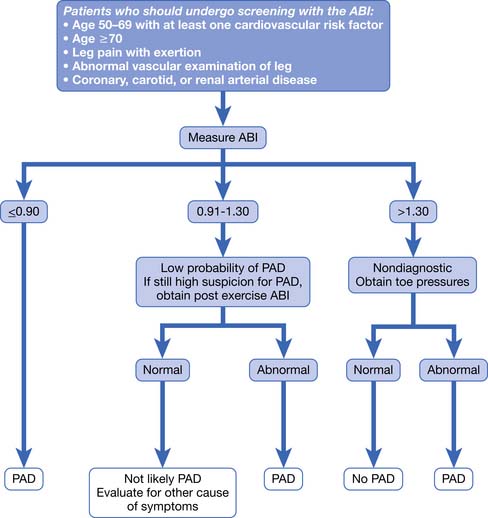

PAD is usually diagnosed with the ABI, which compares the brachial systolic pressure with the ankle systolic pressure (Figure 56-4). An ABI of 0.9 or less is 95% sensitive in detecting PAD compared with angiography. The ABI is inexpensive, simple, and noninvasive, making it an appealing screening test. An ABI should be obtained on all patients over the age of 70, patients aged 50 to 69 who have cardiovascular risk factors, or any patient with symptoms of PAD or an abnormal lower limb vascular exam.40 An ABI of 1.4 or greater is due to incompressible vessel walls at the ankle and is nondiagnostic. Patients with an elevated ABI will need additional testing such as toe pressures to evaluate for the presence of PAD. Patients with a normal ABI but a high suspicion for IC should have the ABI repeated after exercise (Figure 56-5). The ABI is related to prognosis and functional ability, and ABI can be repeated to follow disease progress.

Segmental Limb Systolic Pressure Measurement

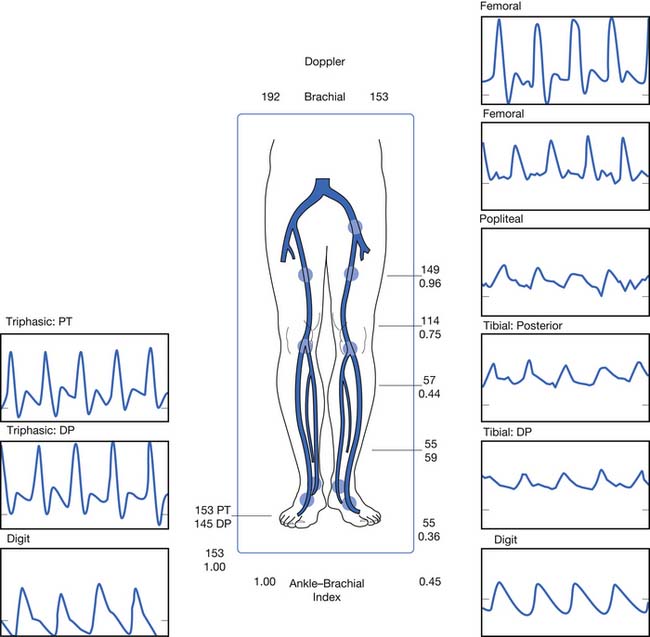

Limb pressures are taken in the thigh, calf, and ankle. Occlusive disease is noted by a significant decrease in systolic pressure from one level to the next (Figure 56-6). Just as with the ABI, incompressible vessel walls can falsely elevate pressures and render the testing inaccurate. Small or moderate lesions can also be missed because they often do not cause a large decrease in pressure.

Segmental Plethysmography (Pulse Volume Recordings)

Pulse volume recordings are measured with a plethysmography attached to limb cuffs, and recordings are obtained at the thigh, calf, and ankle. Occlusive lesions are detected by a change in waveform from one level to the next. The accuracy of testing is greater than either test alone and increases to 95% if pulse volume recordings are combined with segmental limb pressures.57 This test is often not required because most lesions can be localized with Doppler waveform analysis.

Doppler Velocity Waveform Analysis

If a screening ABI is abnormal, Doppler waveform analysis is usually performed to localize the lesion. Doppler waveforms are obtained at multiple sites. Like pulse volume recordings, a change in waveform from one level to the next is indicative of PAD (see Figure 56-6). This test is operator dependent.

Transcutaneous Partial Pressure of Oxygen

Measurement of transcutaneous partial pressure of oxygen (TcPO2) is a useful test to predict wound healing. It can also be used to select amputation level. TcPO2 less than 30 mm Hg is associated with poor wound healing.46 TcPO2 above 40 mm Hg suggests adequate skin perfusion for healing. Readings are taken with electrodes attached to the skin. One is placed on the chest as a control, and the other is placed on the area of interest. Readings require proper positioning and temperature and can take 30 minutes to obtain.

Magnetic Resonance Angiography

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) is safer than intraarterial angiography. MRA sensitivity and specificity are greater than 90% for evaluating PAD.23,38 For these reasons, MRA has become the preferred imaging technique at many institutions. Contraindications are the same as with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in regard to the magnetic field. Some patients are unable to tolerate the procedure because of claustrophobia. Some patients are unable to lie still for the prolonged amount of time required for testing, which can cause motion artifact. There might also be artifact from stents or other hardware in the area of interest. The patient’s renal function needs to be considered before testing because nephrogenic systemic fibrosis is associated with gadolinium administration in patients with impaired renal function.

Multidetector Computed Tomography Angiography

Like MRA, computed tomography angiography (CTA) has a sensitivity and specificity greater than 90% for evaluating PAD.32 CTA is faster than MRA, which makes it more tolerable for some patients. CTA has more risk than MRA but less risk than intraarterial angiography. The risk relates to the use of iodinated contrast and radiation exposure. There can be artifact on imaging from calcium in the vessel wall.

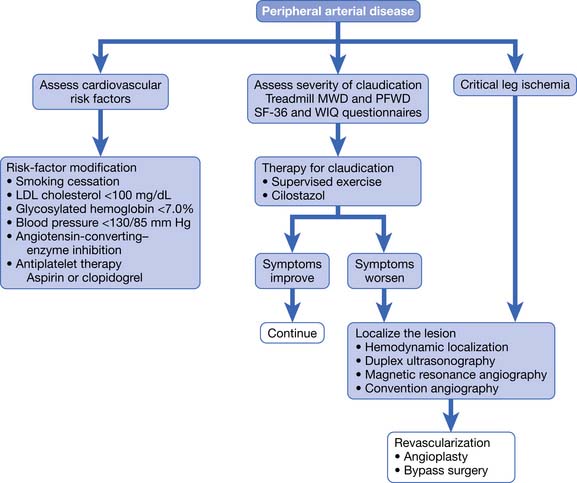

Management of Atherosclerotic Peripheral Arterial Disease

PAD is not only underdiagnosed but it also is undertreated even after being identified.3 When treating patients with PAD, the physician and patient must remember that PAD is part of a systemic vascular disorder. Peripheral, coronary, and cerebral artery diseases are all part of systemic atherosclerosis. Patients with PAD are more likely to have coronary artery disease and cerebral artery disease than patients without PAD. Physicians and patients, however, often do not recognize PAD as an important predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and do not treat it as aggressively as coronary artery disease or cerebral artery disease.

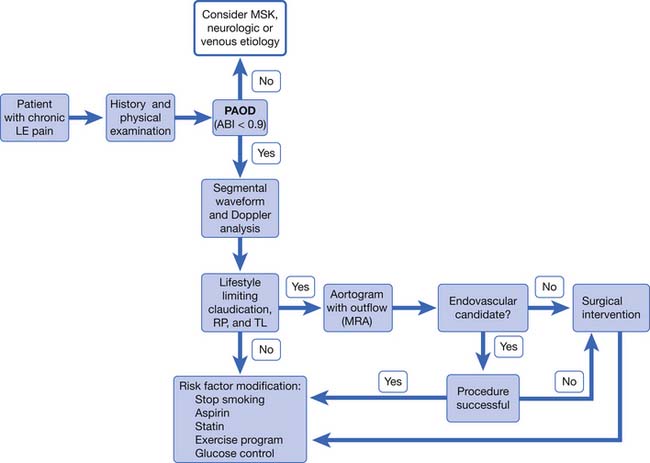

The goals of treatment are to reduce ischemic symptoms, increase walking ability, improve function, prevent and heal wounds, prevent limb loss, and reduce morbidity and mortality. This is best accomplished using a multidisciplinary approach that includes physiatrists, primary care physicians, vascular surgeons, and the patient. Management involves education, risk factor modification, pharmacotherapy, exercise, and vascular interventions (Figure 56-7).

FIGURE 56-7 Treatment of patients with proven peripheral arterial disease.

(From Hiatt WR: Medical treatment of peripheral arterial disease and claudication, N Engl J Med 344:1608-1621, 2001.)

Risk Factor Modification

Management of patients with PAD should always include risk factor modification. Risk factor modification includes smoking cessation, weight reduction, and control of hyperlipidemia, hypertension, and diabetes. Statins have been shown to reduce mortality, coronary events, and strokes in PAD patients.37 Patients with PAD who do not have coronary artery disease should have as a goal a low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol level of less than 100 mg/dL. Patients with PAD and coronary artery disease should have a goal LDL cholesterol level of less than 70 mg/dL.41 If patients do not already have a primary care physician, they should be referred to one for aggressive management of glucose, blood pressure, and cholesterol. Patients can also be referred to a nutritionist for diet education.

It should be made clear to patients that smoking cessation can reduce their risk of amputation and cardiovascular events even if it does not improve claudication symptoms. The patient must understand the connection between continued smoking and higher risk of amputation, as well as a higher risk of cardiovascular events.26 Patients should be referred to smoking cessation programs, and the use of nicotine replacements and bupropion should be considered. Patients should be advised to stop smoking at every visit. Varenicline was recently approved for smoking cessation.

Pain Management

Patients can experience pain from IC, ischemic rest pain, ischemic ulcers, ischemic neuropathy, or concomitant diabetic neuropathy. In some patients, diabetic neuropathy can impair sensation enough that the patient cannot feel ischemic pain. Ischemic pain is best relieved by reperfusion of the limb. Exercise and risk factor modification are recommended as the first line of treatment for IC pain. Patients who continue to have moderate to severe claudication symptoms despite exercise should be evaluated for revascularization. If a patient is not a candidate for revascularization and continues to have moderate to severe IC despite an exercise program, cilostazol can be used.60 Ischemic rest pain and ischemic wounds should be treated with revascularization if the patient is a surgical candidate. Patients might also require opiates for pain control. Some patients develop rest pain at night when they lie down and find that keeping the foot in a dependent position provides relief (as opposed to nocturnal diabetic neuropathic pain, which is not relieved in the dependent position).

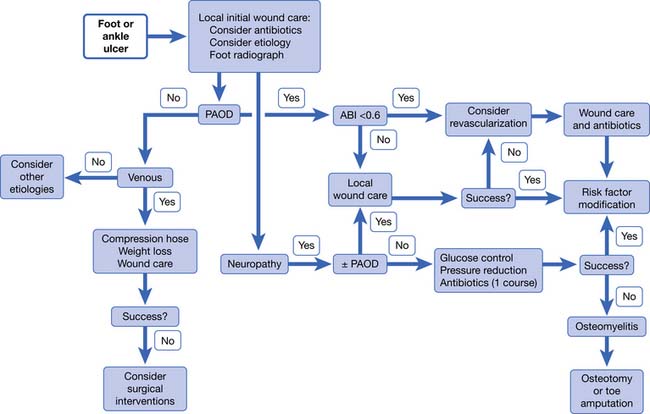

Wounds

Just as with ischemic pain, ischemic wounds are best treated with reperfusion of the limb (Figure 56-8). Wounds can be ischemic or neuroischemic and should be kept clean and free from necrotic debris. Sharp debridement of ischemic wounds must be done with caution because it can increase the area of ischemic necrosis. This is because the surrounding tissue might not have sufficient blood supply to repair itself after the trauma of debridement. Dry gangrene can be allowed to autoamputate as long as there is no evidence of infection and there is adequate perfusion to support healing of the underlying tissue. Appropriate orthoses and off-loading devices should be used to protect the foot from pressure and shear forces. Footwear should cover the foot to protect against trauma and have enough length, breadth, and depth to prevent pressure on the wound.

Dressings should be applied to keep the wound base clean and moist, but there is no good evidence supporting any one type of dressing over another (see Chapter 32). The wound should be monitored for infection and treated immediately if detected. The ischemic foot often has dependent rubor, which can be distinguished from cellulitis by reexamining the limb after a short period of elevation. Dependent rubor should fade with elevation and is not associated with induration or increased warmth. The erythema of cellulitis is often associated with induration, increased warmth, swelling, and does not fully resolve with elevation of the limb.

Patients with ischemic wounds should be evaluated for revascularization. TcPO2 is a useful test to predict wound healing. TcPO2 less than 30 mm Hg is associated with poor wound healing.46 If revascularization is not an option, amputation might be necessary. The physiatrist should be involved preoperatively in determining the level of amputation. The decision should be made based on tissue viability, function, and prosthetic options. Patients who undergo amputation of a limb should receive physical and occupational therapy for transfers, mobility, activities of daily living, and education. Prosthetic limbs should be prescribed for appropriate patients. See Chapter 13, Rehabilitation of People With Lower Limb Amputation, for a more detailed discussion.

Exercise

Exercise can improve walking time and walking distance in PAD patients with or without claudication symptoms.28 Exercise increases pain-free walking distance in patients with a history of IC.68 All patients should begin an exercise program, except those unable to participate in a walking exercise program because of physical, cardiac, or pulmonary reasons. Patients are encouraged to walk until they experience near maximal leg symptoms. Patient then rest until symptoms subside, and then they walk again until they experience near maximal symptoms. The patient should continue this cycle for 30 to 60 minutes two or three times a week.55 Patients without claudication symptoms should be told to exercise at a moderately hard level. Supervised exercise programs have been more successful than home exercise programs. Despite a proven benefit, supervised programs are not readily available. This is likely the result of problems with reimbursement and low patient interest.

Antiplatelet Therapy

The clinical practice guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians recommends lifelong antiplatelet therapy for all patients with PAD, whether or not they have clinically evident coronary or cerebral artery disease.60 The intention of antiplatelet therapy is to prevent mortality and morbidity from myocardial infarction and stroke. Anticoagulation is not recommended.

Surgical Intervention

Revascularization can be through endovascular or open surgical techniques. Endovascular interventions include angioplasty, stenting, thrombolysis, and thrombectomy. Percutaneous balloon transluminal angioplasty (PTA) dilates stenosed arteries. A stent can be placed after angioplasty to decrease the chance of the occlusion recurring. Angioplasty works best in patients with focal, short lesions. Complications of PTA include hematoma, thrombosis, and embolization. Restenosis can occur.

Other surgical interventions include limb salvage and amputation. Limb salvage is an attempt to preserve the foot. Salvage procedures include debridement of wound, excision of bone, and partial foot amputations. If limb salvage is not possible or fails, an amputation at the transtibial or transfemoral level is performed. Please see Chapter 13 for a more detailed discussion about lower limb amputations.

Prognosis

Patients with symptomatic PAD have a 25% 5-year mortality rate.11 An inverse correlation exists between ABI and odds of having a myocardial infarction, stroke, or cardiovascular death.31 The risk particularly escalates once the ABI has decreased to less than 0.50.5 Up to 60% of deaths in PAD patients are from coronary artery disease; up to 20% of deaths are from cerebral artery disease; and another 10% of deaths are from other cardiovascular causes.41 Patients with PAD are at high risk for cardiovascular events and death and should be treated accordingly, with aggressive risk factor modification, cholesterol-lowering medications, and antiplatelet therapy.15

Amputation is not a common outcome for most patients with PAD but is common in certain subsets. The Framingham study found that less than 2% of patients with PAD had amputation as an outcome.20 Patients who are more likely to progress to amputation are those who smoke, have diabetes, have an ABI less than 0.50, have CLI, or have acute limb ischemia. Less than 10% of patients with PAD will develop CLI.13 Patients with PAD and diabetes are more likely to develop CLI. Patients presenting with CLI are at high risk for amputation and death. At 1 year 25% are deceased and 30% of survivors have lost a limb. Those that received a below-knee amputation as the initial primary treatment have 10% perioperative mortality, 30% 2-year mortality, and a 30% risk for further amputation.41

Thromboangiitis Obliterans (Buerger’s Disease)

Introduction

Thromboangiitis obliterans (TAO), also called Buerger’s disease, is a nonatherosclerotic PAD affecting young male smokers. It is an inflammatory disease that affects small- and medium-sized arteries of the upper and lower distal extremities. It also affects the veins and nerves, but it is the arterial aspect that causes the most morbidity. The disease is segmental, meaning there are normal-appearing sections of the artery interspersed with diseased sections. It is characterized by inflammatory thrombus in the small- and medium-sized arteries of the arms and legs that spares the vessel wall. It is considered to be a form of vasculitis.

Men are more affected by TAO than women. The number of affected women has increased, however, and is thought to be due to the increase in the number of women smoking. Although TAO is found worldwide, it is more common in Eastern Europe, the Middle East, and the Far East. It is a common cause of PAD in Japan and India. It is not a common cause of PAD in the United States. Unlike atherosclerotic PAD, life expectancy does not appear to be shortened. The risk of amputation is very high in patients with TAO.52

The cause of TAO is unknown. Although there is a clear and strong link to smoking, the exact disease-causing mechanism is still unknown. Of the patients who continue to smoke, 43% will require an amputation. Of the patients who quit smoking, only 6% will need amputation.42

Clinical Presentation, Evaluation, and Diagnosis of Thromboangiitis Obliterans

Patients typically present with claudication symptoms in the upper or lower limbs. If the patient continues to smoke, the disease will progress to rest pain and ischemic ulcers. Clinically the legs are more involved than the arms. Most patients with TAO, however, will have three or four limbs involved when assessed with angiography, even if they are symptomatic in only one limb.42 There have been case reports of disease in the vascular beds of the heart, lung, brain, kidney, and intestinal tract.17 Although some patients report arthralgias (which can appear long before the ischemic problems and typically resolve spontaneously), there is no erosive arthritis with TAO.

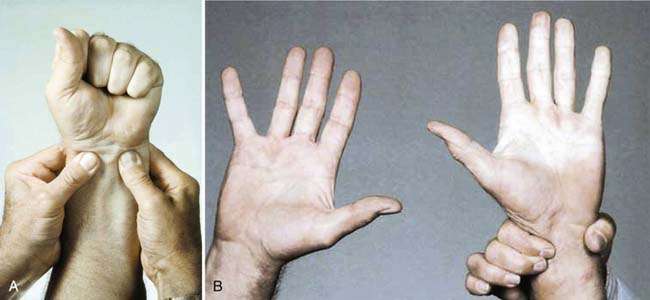

The physician should do a thorough history and physical examination when evaluating a patient suspected to have TAO. A tobacco history should be taken, including smoking and smokeless tobacco use. Pulses should be checked carefully in the upper and lower limbs. When evaluating a patient with leg-only symptoms, the physician can perform an Allen test to assess for asymptomatic involvement of the upper extremities (Figure 56-9). A positive test suggests small artery disease in the upper limbs but is not specific to TAO. Evidence of small artery disease in the lower and the upper limbs places TAO high on the list of differential diagnoses.

FIGURE 56-9 The Allen test.

(From Olin JW, Lie JT: Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). In Cooke JP, Frohlich ED, editors: Current management of hypertensive and vascular diseases, St Louis, 1992, Mosby–Year Book.)

No diagnostic laboratory tests exist for TAO, but testing should be performed to rule out other diagnoses. Testing for autoimmune disorders and other forms of vasculitis should be performed and are negative in patients with TAO. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate and serum C-reactive protein are normal. Patients should be screened for diabetes, hyperlipidemia, and hypercoagulable disorders, which typically are not present in patients with TAO.42

No standard set of diagnostic TAO criteria has been validated, but several criteria have been proposed.33,42,43,59 Commonly accepted criteria are a history of tobacco use, age less than 45, distal limb ischemia, and exclusion of atherosclerosis and autoimmune and hypercoagulable disorders. For diagnostic criteria purposes, patients are considered to have limb ischemia if they have claudication, rest pain, ischemic wounds, or gangrene.

A biopsy should be performed if TAO is suspected, but the clinical picture is not typical. Pathologically the acute phase of TAO shows an occlusive thrombus that is inflammatory but which spares the vessel wall. The vessel wall is not spared in other vasculitides or in atherosclerosis.42

Management of Thromboangiitis Obliterans

Smoking cessation is key to disease management. It must be made clear to patients that to continue smoking means the disease will progress and the risk of amputation will be high (Figure 56-10). Almost all patients who quit smoking can avoid amputation. Patients must understand that they control the outcome of this disease by their choice to continue smoking or not. It has been reported that smokeless tobacco and nicotine replacement patches or gum can cause disease exacerbation and should therefore not be considered as safe alternatives to smoking.24

FIGURE 56-10 Patient with Buerger’s disease.

(From Stone JH: Vasculitis: a collection of pearls and myths, Rheumatic Dis Clin N Am 33:691-739, 2007.)

Revascularization is not usually a successful option for patients with TAO. Because the disease is distal and segmental, there are usually no target vessels for a bypass procedure. Trials for new treatments have been small and limited in the United States. Treatment options that have been or are being investigated either in the United States or abroad include pneumatic compression devices, prostaglandins, thrombolytics, omental transfer, electrical spinal cord stimulation, and angiogenesis. Angiogenesis has been attempted via growth factors by either direct intramuscular injection of the growth factors or gene transfer. Cell therapy has also been investigated using autologous bone marrow injection or stem cell injection. Fenestration of the tibia and intramedullary wire have also been studied.44 Although current research gives hope for the future, the mainstay of therapy continues to be smoking cessation, local wound care, and amputation when required.

Vasospastic Disease (Raynaud’s Phenomenon, Livedo Reticularis, Acrocyanosis)

Raynaud’s Phenomenon

It is estimated that between 5% and 17% of the population might have Raynaud’s phenomenon.27 It is more common in young women and those with a family history of the disorder. Although it can affect both the hands and the feet, the hands are more commonly affected.

Livedo Reticularis

Livedo reticularis has a mottled bluish reticular appearance with no distinct border. It is not blanchable. It is seen on the arms and legs and occasionally the trunk. It is more common in young women. Cold exposure can trigger it. It is usually benign with no associated disease. If it is associated with pain or ulcers or is generalized, the patient should be evaluated for a connective tissue disorder, other underlying disease, or drug-induced etiology.

A case has been reported of a patient with livedo reticularis who required an amputation. Pathologic examination of tissue samples after amputation demonstrated TAO.64 There have also been case reports in children of livedo reticularis developing after initiation of methylphenidate or dextroamphetamine. The physiatrist needs to be aware of this possible association because these are drugs used in rehabilitation medicine.63

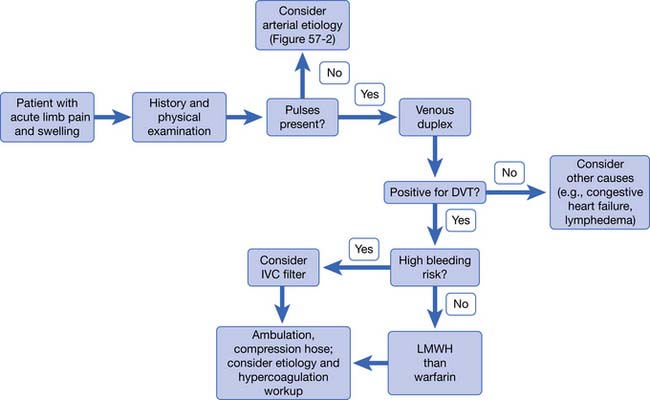

Venous Disorders of the Lower Limb

Venous disorders affect one quarter to one third of the adult population in Western countries and are common in physiatry practice. The morbidity associated with venous disorders affects quality of life and causes work loss.47 Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is the third most common cardiovascular disorder in the United States. The incidence is increasing as the U.S. population is aging and becoming more obese. It is the leading preventable cause of hospital deaths in the United States. Prompt diagnosis and treatment of these conditions is absolutely necessary to prevent morbidity and mortality.

Peripheral venous disorders include the following conditions:

Chronic Venous Insufficiency

Epidemiology of Chronic Venous Insufficiency

CVI is a common but often ignored problem. Venous ulcers caused by CVI account for 80% of all lower limb ulcers.47 The incidence of ulceration and CVI is twice as common in women, but the sequelae of the disease and severity are higher in men than in women. Predisposing factors include occupations that require prolonged standing, obesity, positive family history, multiparity, advanced age, and history of leg injury, surgery, heart failure, paralysis, and DVT. One third of patients with CVI have history of DVT.

Pathogenesis of Chronic Venous Insufficiency

The basic underlying pathophysiologic mechanism in CVI is persistent ambulatory venous hypertension in the superficial and deep venous systems in the lower limbs. To understand the pathogenesis of venous hypertension, a basic review of the lower limb venous system is necessary (Figure 56-11).

Several theories exist in regard to the cutaneous changes that occur with CVI. Current evidence suggests that the increased venous hydrostatic pressure transmitted to dermal microcapillaries leads to increased capillary permeability. This allows escape of fluid, red blood cells, and macromolecules such as fibrinogen into pericapillary tissue, with formation of fibrin cuffs around dermal capillaries. The fibrin cuffs act as a barrier to oxygen diffusion, resulting in tissue hypoxia. Growth factor and cytokines released from the activated leukocytes trapped in the fibrin cuff lead to fibrosis and inflammation.53 Even though initially there is increased capillary permeability, at later stages there can be capillary thrombosis with resultant tissue hypoxia.

Clinical Features of Chronic Venous Insufficiency

The cutaneous manifestation of CVI is characterized by brownish pigmentation, especially along the perimalleolar area, caused by hemosiderin deposits in the skin (Figure 56-12). Some patients can have a reddish purple hue from venous engorgement and obstruction. The secondary weepy pruritus that occurs can induce scratching, eventually leading to eczematous stasis dermatitis, recurrent cellulitis, ulceration, and obliteration of cutaneous lymphatics. Eczema is usually seen in uncontrolled CVI but can be caused by sensitization to local therapy. Patients with severe CVI can develop lipodermatosclerosis and/or atrophie blanche. Lipodermatosclerosis is caused by chronic inflammation and fibrosis of the skin and subcutaneous tissue of the lower leg, and at times is associated with Achilles tendon contracture resulting from scarring. Atrophie blanche is a localized, often circular, whitish atrophic skin surrounded by dilated capillaries and at times hyperpigmentation. It can be mistaken for scarring from healed ulcers (see Figure 56-12).

Physiatrists should be familiar with the CEAP classification system, developed by the International Consensus Conference on Chronic Venous Disorders convened by the American Venous Forum.7 CEAP classification allows the physician to document the severity of clinical manifestations (C), etiology of the CVI (E), anatomic distribution of the venous system involved (A), and pathophysiologic mechanism (P) in one single classification. This allows uniform reporting of research and clinical documentation and can help direct diagnostic testing and the degree and intensity of therapeutic interventions. This was initially developed in 1994 and was revised in 2004. See Box 56-4 for clinical classifications used in CEAP.

Management of Chronic Venous Insufficiency

The optimal pressure required to overcome the abnormal hemodynamics caused by ambulatory venous hypertension remains a matter of debate. Physiologically, intravenous pressure in the leg vein reflects the weight of the blood column between the site of measurement and the right atrium. In the supine position, the leg vein venous pressure will be between 10 and 20 mm Hg. Studies have shown that an external pressure of 10 to 20 mm Hg narrows the leg veins in the supine position and can totally occlude them at higher pressures of 20 to 25 mm Hg. Thromboembolic stockings exert a pressure between 14 and 20 mm Hg. During standing, intravenous pressure in the lower leg veins will be around 60 mm Hg, depending on the height of the individual. An external pressure of 35 to 40 mm Hg has been shown to narrow the veins in the standing position, and 60 mm Hg will totally occlude the veins in the standing position. For mild disease and those with underlying arterial disease, compression stockings with 20 to 30 mm Hg pressure are indicated. For moderate to severe disease, 30 to 40 mm Hg pressure is appropriate. The stockings need to be replaced every 4 to 6 months because they tend to lose elasticity and pressure over time. Compression stockings are difficult to don and might require use of a zipper. Use of an inner silk liner fitted on the toe, kitchen gloves, or a “butler device” (which holds the stockings open) might make it easier to don the stockings.35

Intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC) devices can improve microcirculatory changes seen in CVI and can be used as an adjunctive device for edema control and ulcer healing. These are useful in patients with significant edema and morbid obesity. IPC devices provide sequential gradient compression and might be useful in treatment of refractory venous ulcers that do not heal with ambulatory compression alone and in patients who cannot tolerate compression bandages or stockings.39 Contraindications for IPC include DVT, active infection, uncontrolled congestive cardiac failure, and significant arterial insufficiency.

Medications for Chronic Venous Insufficiency

Short-term use of diuretics helps reduce edema but generally does not help with the pain or discomfort associated with CVI. Use of systemic antibiotics should be limited to cases having obvious infection of the ulcer, periwound cellulitis, and septicemia. Aspirin, 325 mg/day, has been shown to provide additional benefit to compression therapy.18 Pentoxifylline, 1200 mg/day, also appears to promote healing when used in conjunction with compression therapy.19 Venotrophic drugs, which improve venous tone and flow, are used in European countries for treatment of CVI. Flavonoids and horse chestnut seed extract fall into this category. Horse chestnut seed extract (Aescin), an herbal remedy, has been shown to decrease pain, pruritus, and edema by preventing leukocyte activation and increasing venous tone and venous flow when used in conjunction with compression therapy.2,4,48 A Cochrane Review of 17 randomized controlled trials has shown short-term improvement in signs and symptoms of CVI with use of horse chestnut seed extract; however, it is not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration at this time.

Venous Ulceration

Ulceration is the disabling complication of CVI. Venous ulcers are most often large, irregular in shape, and have a flat wound edge with a shallow moist ruddy or beefy granulation base. The majority of venous ulcers are located along the medial or lateral aspect of the leg in the supramalleolar area (see Figure 56-12). Venous ulcer formation risk is highest when the ambulatory venous pressure is 80 mm Hg or greater.

Treatment of venous leg ulcers begins with meticulous local wound care and careful attention to the skin surrounding the ulcer. Local wound care should include sharp or enzymatic debridement for removal of nonviable tissue to decrease the bacterial bioburden, control bacterial colonization, and cleanse the wound. Optimal wound dressing should provide moisture and temperature balance. Many topical wound care products are available. Many are costly, and efficiency beyond standard compression therapy has not been demonstrated. Thomas and O’Donnell65 conducted a systematic review of all randomized controlled trials published on wound dressings since 1997 through 2004 on treatment of venous ulcers and other chronic wounds. For uncomplicated wounds, they recommend treatment with occlusive dressings such as Tegasorb or Viscopaste because they provide constant mild rigid compression and a decreased frequency of dressing changes. Their review also supported use of Xenograft Oasis for noninfected wounds with some degree of granulation tissue and Apligraf for hard to heal large wounds.65

The most common methods of compression are Unna boot and multilayer compression bandages. Unna boots are made with a paste containing zinc oxide, gelatin, sorbitol, magnesium sulfate, and glycerin. Unna boots dry to a semirigid consistency when applied. The Unna boot is changed weekly or sooner if there is significant drainage or discomfort. The advantage of the Unna boot is minimal patient involvement while providing continued compression. Disadvantages are that some patients find it uncomfortable to wear, and it can cause contact dermatitis. The multilayer system Profore (Smith + Nephew United, London, UK) and Dyna-Flex Multi-layer compression system (Johnson & Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ) are better tolerated. Profore involves sequential application of (1) orthopedic wool wrap, which absorbs exudate and protects bony eminence; (2) crepe bandage, adding absorbency; (3) light-compression bandage, which is highly conformable to accommodate a difficult limb shape; and (4) a cohesive flexible bandage that applies pressure, maintaining effective levels of compression up to 1 week.8 This system provides 40 mm Hg pressure at the ankle in resting position, which decreases to 17 mm Hg below the knee. In one study using this therapy, 74% of 148 ulcerated limbs had ulcer healing by 12 weeks. Profore should not be used in patients with an ABI less than 0.8. Profore Lite should not be used in patients with an ABI less than 0.6. Circ-Aid is a legging orthosis and is another option available for compression. It provides inelastic rigid compression. Because its bands are adjustable, it is easier to don and is adjustable as the limb edema decreases.

Venous Thromboembolism

Epidemiology of Venous Thromboembolism

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data, the annual U.S. incidence of DVT and PE is 300,000 to 600,000 (of which 200,000 to 400,000 are PE). Nearly one third of patients who have PE die. VTE is primarily a disease of old age. The incidence increases exponentially with age, with a relative risk of 1.9 for each 10-year increase in age for both men and women. The overall male/female incidence ratio is 1.2:1. The incidence is higher in women in childbearing years. African Americans and whites have a higher incidence of VTE than Asians, Pacific Islanders, Hispanics, and Native Americans.25 Two thirds of VTE cases are associated with recent hospitalizations, and half of all DVT episodes occur in hospitalized or nursing home residents.54 Approximately 90% of DVTs occur in lower limbs; however, with frequent instrumentation and improved diagnostic testing, it is increasingly being recognized in upper limbs as well. Rarely, DVT occurs in cerebral sinuses, mesenteric arteries, and the retina.

Recurrence of DVT and PE is higher in the first 6 to 12 months, and cumulative recurrence rate can be as high as 24% at 5 years and 30% at 8 years after the initial episode.50 Hansson et al.12 in their study of 738 patients found a higher incidence of recurrence in patients with residual thrombus, idiopathic DVT, proximal DVT, cancer, history of thromboembolic events, and short duration of anticoagulant therapy. Patients with postoperative DVT had a lower recurrence rate in their study.

Pathogenesis of Venous Thromboembolism

Many factors, genetic and environmental, contribute to the development of DVT. Primary or idiopathic DVT occurs in the absence of recognized thrombotic risk factors, whereas secondary DVT occurs in the presence of known risk factors. Approximately 80% of inpatients with VTE and 30% of outpatients with confirmed DVT have been shown to have three or more risk factors. The Virchow’s Triad of (1) venous stasis, (2) vessel wall injury, and (3) variation in coagulability of the blood comprises the critically important contributors in the pathogenesis of DVT. (See Table 56-1 for risk factors that are associated with each of these contributors.) Each of these factors plays variable roles in individual patients.

| Stasis | Hypercoagulable State | Endothelial Injury |

|---|---|---|

| Age (older than 60) | Estrogenic medications | Postoperative state |

| Immobility | Pregnancy | Venous access |

| Paralysis | Cancer | Trauma, burn |

| Heart failure/myocardial infarction | Family history | Spinal cord injury |

| Anesthesia during surgery | Sepsis | Sepsis |

| Obesity | Inherited hypercoagulable state | Vasculitis |

| Long-distance travel | Factor V Leiden mutation | Prior deep venous thrombosis |

Thrombi usually begin to form at low flow sites, such as the deep veins of the calf, soleus sinuses, behind the cusps of venous valves, and at the entrance of tributary veins.62 Surgery of hip and knee, venous catheterization, and burns can cause vessel wall damage that initiates thrombus formation. Vascular endothelium is generally considered to be nonthrombogenic; however, when endothelium is damaged, platelets interact with subendothelial constituents and initiate thrombus formation with activation of coagulation factors. Venous thrombi consist of deposits of fibrin, red cells, and variable amount of platelets and leukocytes.16 Clearance of activated coagulation factors is prevented by venous stasis and facilitates interaction of thrombus with the vessel wall. The relative balance between activated coagulation and the thrombolytic system determines further propagation and dissolution of thrombus. It is fortunate that many small calf vein thrombi undergo rapid dissolution without therapy and rarely cause clinically significant PE. Although calf thrombi are regarded as an unusual source of symptomatic PE, they have been associated with high probability lung scans in up to 29% of patients with isolated calf vein thrombi.

Most clinically significant PE originates from DVT of the proximal lower limb (popliteal, femoral, or iliac veins).36 Ninety percent of pulmonary emboli are associated with proximal lower limb venous thrombosis. Organization of large thrombi usually results in anatomic and functional changes in the vein. These changes include vein wall fibrosis, venous outflow obstruction, and valvular incompetence. These changes result in reflux and postthrombotic CVI. Recanalization of proximal venous thrombi occurs in fewer than 10% of patients and can take several months or more. The incidence of postthrombotic syndrome is 6 times higher in patients with recurrent thrombosis.

History and Clinical Features of Venous Thromboembolism

The evaluation for suspected VTE begins with a careful history and physical examination. Relevant history in these patients includes the patient’s symptoms and assessment of potential risk factors. No single physical finding or combination of symptoms and signs is sufficiently accurate to clinically establish the diagnosis of VTE. Classic signs of edema, erythema, warmth, tenderness, and positive Homan’s sign are nonspecific and might not be always present. In fact, Homan’s sign can be present in 50% of those without DVT. DVT is confirmed in only 50% of thosewith leg pain, tenderness, and swelling, only 20% of those with leg pain and tenderness, and only 11% of those with isolated swelling. Patients can present with unilateral edema and tenderness confined to the calf muscle or along the distribution of the deep veins of medial thigh without any other signs. A 3-cm or greater difference in calf circumference 10 cm below the tibial tuberosity is associated with a high likelihood of having DVT.61 The clinical presentation varies with anatomic location and extent and degree of occlusion by the thrombus. Patients with obstructive iliofemoral thrombosis can present with a markedly swollen, cyanosed leg or with a white, cold leg if there is associated arterial spasm. In some cases the presenting signs and symptoms might include apprehension, diaphoresis, tachycardia, pleuritic chest pain, tachypnea, and light headedness caused by sudden hypotension. It is essential to confirm the clinical suspicion of venous thrombosis with objective testing. (See Table 56-2 for signs and symptoms of PE.)

| Symptoms | Signs |

|---|---|

Modified from Cloutier S, Ginsberg JS: Venous thromboembolism. In Rajagopalan S, Mukkerjee D, Mohler ER III, editors: Manual of vascular diseases, Philadelphia, 2005, Lippincott Williams Wilkins.

Diagnostic Evaluation of Venous Thromboembolism

Duplex Ultrasound for Deep Venous Thrombosis

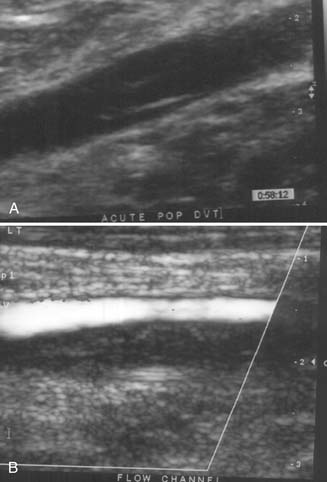

Duplex ultrasound is the diagnostic test of choice for detection of DVT, replacing contrast venography and impedance plethysmography (Figure 56-13). Essential elements of duplex ultrasound examination include thrombus visualization, venous compressibility, and detection of venous flow. Noncompressibility of femoral and popliteal vein is diagnostic of proximal DVT. New thrombi are hypoechogenic, as opposed to chronic thrombi, which are echodense. The diagnostic sensitivity of duplex ultrasound for proximal DVT is high (94.2%) but is low (63.5%) for nonoccluding or isolated calf thrombi. Because there is 20% to 30% incidence of propagation of calf thrombi to the proximal venous system, repeat or serial ultrasound studies are recommended in 7 to 14 days for patients in whom a clinical concern remains despite initial negative results on examination.

D-Dimer Assay

d-dimer is a degradation product of cross-linked fibrin blood clot. Elevated levels of d-dimer occur with acute thrombosis, but this does not discriminate between physiologic (e.g., postoperative or posttrauma) or pathologic (e.g., deep vein) thrombi. d-dimer levels can be elevated in patients with cancer, recent trauma, surgery, sepsis, late pregnancy, hemorrhage, and many other medical conditions. d-dimer assay is a sensitive but nonspecific test. It offers greater benefit in outpatient testing than in the inpatient setting because inpatients more often tend to have the above-noted conditions that cause false-positive results. A study done in a rehabilitation inpatient population, however, showed d-dimer assay to be an effective screening test in suspected cases of DVT and can reduce the need for more expensive diagnostic workup.1

Wells et al.69,70 have developed a structured clinical prediction rule to standardize clinical assessment for patients with suspected PE and DVT. The assessment is based on the patient’s signs and symptoms, risk factors for VTE, and presence of alternative diagnosis. Patients are stratified into low, moderate, or high probability for DVT or PE based on the resultant score. A combination of Wells pretest probability score and quantitative d-dimer testing has been used to reduce the number of diagnostic tests performed in patients with suspected VTE in the outpatient setting, but this has not been validated for inpatients.

Diagnostic Testing for Pulmonary Embolism

Treatment of Acute Venous Thromboembolism

If UFH is used, it is initiated with an intravenous bolus dose followed by continuous infusion. Patients require regular monitoring of activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) with heparin dose adjusted to achieve aPTT target range of 1.5 to 2.5 times the normal for 2 consecutive days. LMWH or UFH should be continued for at least 5 days to minimize risk of extension of thrombosis or recurrence of PE. Warfarin therapy is started within 24 hours of heparin treatment. The initial starting dose is 5 to 10 mg/day. The dosage is subsequently adjusted according to the patient’s international normalized ratio to therapeutic range of 2.0 to 3.0. Warfarin therapy should overlap heparin therapy for at least 5 days, bridging to long-term therapy for at least 3 months with oral anticoagulant. Bleeding is the main complication of anticoagulation and requires careful monitoring depending on the clinical condition of the patient and the drug used.

Inferior Vena Cava Filter

Placement of an inferior vena cava filter is indicated for patients with acute DVT who have an absolute contraindication for anticoagulation. Contraindications to anticoagulation include acute hemorrhage, neurosurgery, or intracranial bleeding within 7 days, severe thrombocytopenia, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia within 90 days, and recent gastrointestinal bleed. Patients with recurrent VTE despite anticoagulation, pulmonary hypertension with reduced cardiac reserve, or free-floating iliofemoral thrombi are also candidates for inferior vena cava filter.34

Ambulation After DVT

Historically, bed rest for several days was thought to be the safest for preventing PE in patients with proximal DVT. Recent literature has not supported this. In fact, recent studies have shown that early, and even immediate, ambulation after initiation of appropriate anticoagulation therapy in conjunction with compression therapy does not increase development of symptomatic PE.45,66 Postthrombotic sequelae occur in almost half of all patients with proximal DVT. Initiation of early ambulation results in faster reduction of pain and swelling and less incidence of postthrombotic sequelae.

Adjunctive therapy with graduated below-knee stockings with 30 to 40 mm Hg pressure at the ankle is indicated after proximal DVT. Compression stockings have been shown to reduce the development of postthrombotic sequelae by approximately 50% when worn at least for the first 2 years.49

Prevention of Deep Venous Thrombosis and Pulmonary Embolism

It is recommended that physicians follow clinical guidelines from the American College of Chest Physicians for VTE prophylaxis in rehabilitation patients (Tables 56-3 and 56-4). The type, intensity, and duration of anticoagulation should be adjusted for the individual patient depending on perceived bleeding risk. In addition, patients should be mobilized as early as medical safety allows. Routine screening for DVT or PE in asymptomatic postoperative orthopedic patients is not recommended.

Table 56-3 CHEST Clinical Practice Guidelines for Hospital Thromboprophylaxis

| Total Hip Replacement | Total Knee Replacement | Acute Spinal Cord Injury |

|---|---|---|

INR, International normalized ratio; LDUH, low-dose unfractionated heparin; LMWH, low-molecular-weight heparin.

From Hirsh J, Guyatt G, Albert, G, et al: Antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines, Chest 133:71S-109S, 2008.

Table 56-4 Levels of Thromboembolism Risk and Recommended Thromboprophylaxis in Hospital Patients ∗

| Levels of Risk | Approximate DVT Risk Without Thromboprophylaxis† | Suggested Thromboprophylaxis Options‡ |

|---|---|---|

| Low risk | ||

| <10% | ||

| Moderate risk | ||

| 10%-40% | ||

| Moderate VTE risk plus high bleeding risk | Mechanical thromboprophylaxis | |

| High risk | ||

| Hip or knee arthroplasty, hip fracture surgery | 40%-80% | |

| High VTE risk plus high bleeding risk | Mechanical thromboprophylaxis§ |

DVT, Deep venous thrombosis; INR, international normalized ratio; LDUH, low-dose unfractionated heparin; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

∗ The descriptive terms are purposefully left undefined to allow individual clinician interpretation.

† Rates based on objective diagnostic screening for asymptomatic DVT in patients not receiving thromboprophylaxis.

‡ See relevant section in this chapter for specific recommendations.

§ Mechanical thromboprophylaxis includes intermittent pneumatic compression or venous foot pumps and/or graduated compression stockings; consider switch to anticoagulant thromboprophylaxis when high bleeding risk decreases.

From Charles M, et al: Prevention of venous thromboembolism, in the antithrombotic and thrombolytic therapy, ACCP guidelines supplement, Chest 133:381S-453S, 2008.

Lymphatic Disease in the Lower Limbs

Lymph capillaries begin as closed tubes and lie close to blood capillaries. They do not have valves. Lymph capillaries flow into lymph precollectors, and then collectors, which do have valves. The lymph collectors transport lymphatic fluid to the lymph nodes where the fluid is filtered. Lymph then flows into the lymphatic trunks and then on to the venous angles where it is returned to the venous system.

Lymphedema is caused by a defect in the lymphatic system that leads to protein-rich interstitial fluid overload. The defect can be hereditary, congenital, or acquired. Hereditary and congenital types are called primary lymphedema. Acquired types are called secondary lymphedema (Box 56-5).

Primary lymphedema is less common and has many causes. It can be divided into three major types: congenital, lymphedema praecox, and lymphedema tarda. Congenital lymphedema has an onset in the first 1 to 2 years of life, is noted by aplastic lymphatics, and is bilateral. It can be sporadic or familial and is thought to be due to a gene defect that is involved in lymphangiogenesis. Lymphedema praecox has an onset between ages 1 and 35, is noted by hypoplastic lymphatics, and is generally unilateral. Lymphedema tarda has an onset after age 35 and is noted by weakened lymphatics that are unable to compensate when stressed with overload or injury.22

Secondary lymphedema is the most common type of lymphedema. In developed countries, secondary lymphedema is usually the result of cancer or cancer treatment. In developing countries, the most common cause is filariasis, which is a nematode infection. Many other causes of secondary lymphedema exist, including CVI, infection, trauma, and obesity. Secondary lymphedema typically presents with unilateral painless swelling (Figure 56-14). Patients at high risk of developing lymphedema, such as those who are status postresection or postradiation of lymph nodes, should observe appropriate precautions. Precautions include meticulousskin and nail care and avoiding anything that can lead to swelling or infection in the limb, such as needle sticks, blood pressure cuffs, tight clothing, or leaving the limb in the dependent position for long periods.

The initial clinical presentation of lymphedema is pitting edema, but it becomes nonpitting as the tissues become fibrotic. The skin gradually thickens, and skin folds become accentuated. The skin can become verrucous and hyperpigmented. The patient complains that the limb feels heavy and stiff. As edema and fibrosis worsen, range of motion in the limb becomes impaired. Patients might have difficulty with mobility and activities of daily living. They can have trouble fitting into normal clothing. Many patients experience anxiety, depression, and poor self-image because of the disfigurement and impairment.

1. Akman M.N., Cetin N., Bayramoglu M., et al. Value of the d-dimer test in diagnosing deep vein thrombosis in rehabilitation inpatients. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2004;85(7):1091-1094.

2. Bartholomew J. Approach to and management of varicose veins. In: Rajagopalan S., Mukherjes D., Mohler E., editors. Manual of vascular diseases. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

3. Bhatt D.L., Steg P.G., Ohman E.M., et al. International prevalence, recognition, and treatment of cardiovascular risk factors in outpatients with atherothrombosis. JAMA. 2006;295(2):180-189.

4. Diehm C., Trampisch H.J., Lange S., et al. Comparison of leg compression stocking and oral horse-chestnut seed extract therapy in patients with chronic venous insufficiency. Lancet. 1996;347(8997):292-294.

5. Dormandy J.A., Murray G.D. The fate of the claudicant: a prospective study of 1969 claudicants. Eur J Vasc Surg. 1991;5(2):131-133.

6. Dumville J.C., Lee A.J., Smith F.B., et al. The health-related quality of life of people with peripheral arterial disease in the community: the Edinburgh artery study. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54(508):826-831.

7. Eklof B., Rutherford R.B., Bergan J.J., et al. Revision of the ceap classification for chronic venous disorders: consensus statement. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40(6):1248-1252.

8. Ellason J., Wakefield T. Approach to and management of chronic venous insufficiency. In: Rajagopalan S., Mukherjes D., Mohler E., editors. Manual of vascular diseases. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2005.

9. Fowkes F.G., Housley E., Cawood E.H., et al. Edinburgh artery study: prevalence of asymptomatic and symptomatic peripheral arterial disease in the general population. Int J Epidemiol. 1991;20(2):384-392.

10. Gloviczki P. Development and anatomy of the venous system. In Gloviczki P., editor: Handbook of venous disorders: Guidelines of the American Venous Forum, ed 3, New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

11. Hankey G.J., Norman P.E., Eikelboom J.W. Medical treatment of peripheral arterial disease. JAMA. 2006;295(5):547-553.

12. Hansson P.O., Sorbo J., Eriksson H. Recurrent venous thromboembolism after deep vein thrombosis: incidence and risk factors. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(6):769-774.

13. Hiatt W.R. Medical treatment of peripheral arterial disease and claudication. N Engl J Med. 2001;344(21):1608-1621.

14. Hirsch A.T., Criqui M.H., Treat-Jacobson D., et al. Peripheral arterial disease detection, awareness, and treatment in primary care. JAMA. 2001;286(11):1317-1324.

15. Hirsch A.T., Haskal Z.J., Hertzer N.R., et al. ACC/AHA 2005 guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease (lower extremity, renal, mesenteric, and abdominal aortic): Executive summary a collaborative report from the American Association for Vascular Surgery/Society for Vascular Surgery, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine and Biology, Society of Interventional Radiology, and the ACC/AHA Task Force on Practice Guidelines (writing committee to develop guidelines for the management of patients with peripheral arterial disease) endorsed by the American Association of Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Rehabilitation; National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; Society for Vascular Nursing; Transatlantic Inter-society Consensus; and Vascular Disease Foundation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(6):1239-1312.

16. Hirsh J., Hoak J. Management of deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism: a statement for healthcare professionals, Council on thrombosis (in consultation with the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology), American Heart Association. Circulation. 1996;93(12):2212-2245.

17. Hoppe B., Lu J.T., Thistlewaite P., et al. Beyond peripheral arteries in Buerger’s disease: angiographic considerations in thromboangiitis obliterans. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2002;57(3):363-366.

18. Ibbotson S.H., Layton A.M., Davies J.A., et al. The effect of aspirin on haemostatic activity in the treatment of chronic venous leg ulceration. Br J Dermatol. 1995;132(3):422-426.

19. Jull A., Waters J., Arroll B. Pentoxifylline for treatment of venous leg ulcers: a systematic review. Lancet. 2002;359(9317):1550-1554.

20. Kannel W.B., Skinner J.J.Jr., Schwartz M.J., et al. Intermittent claudication. Incidence in the framingham study. Circulation. 1970;41(5):875-883.

21. Kelsey L.J., Fry D.M., VanderKolk W.E. Thrombosis risk in the trauma patient. Prevention and treatment. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 2000;14(2):417-430.

22. Kerchner K., Fleischer A., Yosipovitch G. Lower extremity lymphedema update: pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment guidelines. J Am Acad Dermato. 2008;59(2):324-331.

23. Koelemay M.J., Legemate D.A., Reekers J.A., et al. Interobserver variation in interpretation of arteriography and management of severe lower leg arterial disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2001;21(5):417-422.

24. Lawrence P.F., Lund O.I., Jimenez J.C., et al. Substitution of smokeless tobacco for cigarettes in Buerger’s disease does not prevent limb loss. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48(1):210-212.

25. Lloyd-Jones D., Adams R., Carnethon M., et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2009 update: a report from the American Heart Association statistics committee and stroke statistics subcommittee. Circulation. 2009;119(3):e21-181.

26. Lu J.T., Creager M.A. The relationship of cigarette smoking to peripheral arterial disease. Rev Cardiovasc Med. 2004;5(4):189-193.

27. Maricq H.R., Carpentier P.H., Weinrich M.C., et al. Geographic variation in the prevalence of Raynaud’s phenomenon: Charleston, SC, USA, vs Tarentaise, Savoie, France. J Rheumatol. 1993;20(1):70-76.

28. McDermott M.M., Ades P., Guralnik J.M., et al. Treadmill exercise and resistance training in patients with peripheral arterial disease with and without intermittent claudication: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009;301(2):165-174.

29. McDermott M.M., Criqui M.H., Greenland P., et al. Leg strength in peripheral arterial disease: associations with disease severity and lower-extremity performance. J Vasc Surg. 2004;39(3):523-530.

30. McDermott M.M., Greenland P., Liu K., et al. Leg symptoms in peripheral arterial disease: associated clinical characteristics and functional impairment. JAMA. 2001;286(13):1599-1606.

31. Mehler P.S., Coll J.R., Estacio R., et al. Intensive blood pressure control reduces the risk of cardiovascular events in patients with peripheral arterial disease and type 2 diabetes. Circulation. 2003;107(5):753-756.

32. Met R., Bipat S., Legemate D.A., et al. Diagnostic performance of computed tomography angiography in peripheral arterial disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301(4):415-424.

33. Mills J.L., Porter J.M. Buerger’s disease: A review and update. Semin Vasc Surg. 1993;6(1):14-23.

34. Minichiello T., Fogarty P.F. Diagnosis and management of venous thromboembolism. Med Clin North Am. 2008;92(2):443-465. x

35. Moneta L. Compression therapy for venous ulceration. In: Gloviczki P., editor. Handbook of venous disorders: Guidelines of the American Venous Forum. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

36. Moser K.M., LeMoine J.R. Is embolic risk conditioned by location of deep venous thrombosis? Ann Intern Med. 1981;94(4 pt 1):439-444.

37. MRC/BHF heart protection study of cholesterol lowering with simva-statin in 20,536 high-risk individuals: a randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;360(9326):7-22.

38. Nelemans P.J., Leiner T., de Vet H.C., et al. Peripheral arterial disease: meta-analysis of the diagnostic performance of MR angiography. Radiology. 2000;217(1):105-114.

39. Nelson E.A., Mani R., Vowden K. Intermittent pneumatic compression for treating venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD001899.

40. Norgren L., Hiatt W.R. Why TASC II? Vasc Med. 2007;12(4):327.

41. Norgren L., Hiatt W.R., Dormandy J.A., et al. Inter-society consensus for the management of peripheral arterial disease (TASC II). J Vasc Surg. 2007;45(suppl S):S5-67.

42. Olin J.W. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease). N Engl J Med. 2000;343(12):864-869.

43. Papa M.Z., Rabi I., Adar R. A point scoring system for the clinical diagnosis of Buerger’s disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;11(3):335-339.

44. Paraskevas K.I., Liapis C.D., Briana D.D., et al. Thromboangiitis obliterans (Buerger’s disease): searching for a therapeutic strategy. Angiology. 2007;58(1):75-84.

45. Partsch H. Ambulation and compression after deep vein thrombosis: dispelling myths. Semin Vasc Surg. 2005;18(3):148-152.

46. Peripheral arterial disease in people with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26(12):3333-3341.

47. Phillips T., Stanton B., Provan A., et al. A study of the impact of leg ulcers on quality of life: financial, social, and psychologic implications. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31(1):49-53.

48. Pittler M.H., Ernst E. Horse-chestnut seed extract for chronic venous insufficiency: a criteria-based systematic review. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134(11):1356-1360.

49. Prandoni P., Lensing A.W., Prins M.H., et al. Below-knee elastic compression stockings to prevent the post-thrombotic syndrome: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(4):249-256.

50. Prandoni P., Lensing A.W., Prins M.H., et al. Residual venous thrombosis as a predictive factor of recurrent venous thromboembolism. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(12):955-960.

51. Price J.F., Mowbray P.I., Lee A.J., et al. Relationship between smoking and cardiovascular risk factors in the development of peripheral arterial disease and coronary artery disease: Edinburgh artery study. Eur Heart J. 1999;20(5):344-353.

52. Puechal X., Fiessinger J.N. Thromboangiitis obliterans or Buerger’s disease: challenges for the rheumatologist. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2007;46(2):192-199.

53. Raffetto J. Venous ulcer formation and healing at cellular levels. In: Gloviczki P., editor. Handbook of venous disorders: Guidelines of the American Venous Forum. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

54. Ramzi D.W., Leeper K.V. DVT and pulmonary embolism. I. Diagnosis, Am Fam Physician. 2004;69(12):2829-2836.

55. Regensteiner J.G. Exercise rehabilitation for the patient with intermittent claudication: a highly effective yet underutilized treatment. Curr Drug Targets Cardiovasc Haematol Disord. 2004;4(3):233-239.

56. Riklin C., Baumberger M., Wick L., et al. Deep vein thrombosis and heterotopic ossification in spinal cord injury: a 3 year experience at the Swiss Paraplegic Centre Nottwil. Spinal Cord. 2003;41(3):192-198.

57. Rutherford R.B., Lowenstein D.H., Klein M.F. Combining segmental systolic pressures and plethysmography to diagnose arterial occlusive disease of the legs. Am J Surg. 1979;138(2):211-218.

58. Selvin E., Marinopoulos S., Berkenblit G., et al. Meta-analysis: glycosylated hemoglobin and cardiovascular disease in diabetes mellitus. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(6):421-431.

59. Shionoya S. What is Buerger’s disease? World J Surg. 1983;7(4):544-551.

60. Sobel M., Verhaeghe R. Antithrombotic therapy for peripheral artery occlusive disease: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines (ed 8). Chest. 2008;133(suppl 6):815S-843S.

61. Stein P. Deep venous thrombosis of the lower extremities: a clinical evaluation. In Pulmonary embolism, ed 2. Malden, MA: Blackwell Futura; 2007.

62. Stein P. Pulmonary embolism and deep venous thrombosis at autopsy. Pulmonary embolism, ed 2. Malden, MA: Blackwell Futura; 2007.

63. Syed R.H., Moore T.L. Methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine-induced peripheral vasculopathy. J Clin Rheumatol. 2008;14(1):30-33.

64. Takanashi T., Horigome R., Okuda Y., et al. Buerger’s disease manifesting nodular erythema with livedo reticularis. Intern Med. 2007;46(21):1815-1819.

65. Thomas F., O’Donnell J. Local treatment of venous ulcers. In: Gloviczki P., editor. Handbook of venous disorders: Guidelines of the American Venous Forum. New York: Oxford University Press, 2009.

66. Trujillo-Santos J., Perea-Milla E., Jimenez-Puente A., et al. Bed rest or ambulation in the initial treatment of patients with acute deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism: findings from the Riete registry. Chest. 2005;127(5):1631-1636.

67. Wahl W.L., Brandt M.M., Ahrns K.S., et al. Venous thrombosis incidence in burn patients: preliminary results of a prospective study. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2002;23(2):97-102.

68. Watson L., Ellis B., Leng G.C. Exercise for intermittent claudication. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(4):CD000990.

69. Wells P.S., Anderson D.R., Bormanis J., et al. Value of assessment of pretest probability of deep-vein thrombosis in clinical management. Lancet. 1997;350(9094):1795-1798.

70. Wells P.S., Anderson D.R., Rodger M., et al. Derivation of a simple clinical model to categorize patients probability of pulmonary embolism: increasing the models utility with the simplired d-dimer. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83(3):416-420.

71. Yablon S.A., Rock W.A.Jr., Nick T.G., et al. Deep vein thrombosis: prevalence and risk factors in rehabilitation admissions with brain injury. Neurology. 2004;63(3):485-491.