Lower Limb

ADDITIONAL LEARNING RESOURCES for Chapter 6, Lower Limb, on STUDENT CONSULT (www.studentconsult.com):

Conceptual overview

General introduction

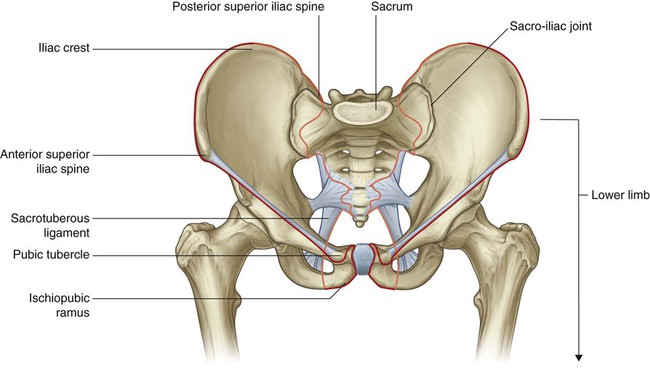

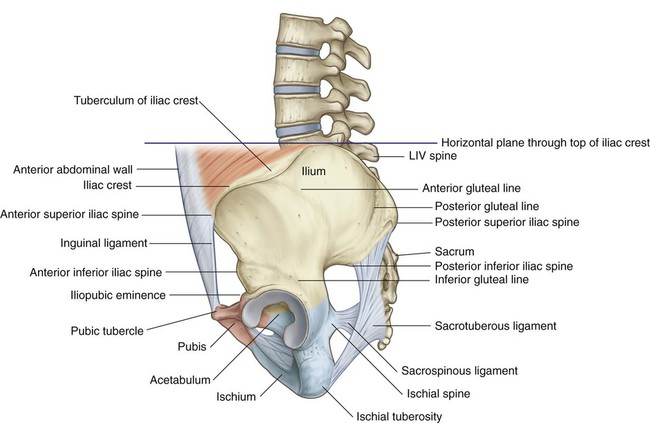

The lower limb is directly anchored to the axial skeleton by a sacroiliac joint and by strong ligaments, which link the pelvic bone to the sacrum. It is separated from the abdomen, back, and perineum by a continuous line (Fig. 6.1), which:

joins the pubic tubercle with the anterior superior iliac spine (position of the inguinal ligament) and then continues along the iliac crest to the posterior superior iliac spine to separate the lower limb from the anterior and lateral abdominal walls;

joins the pubic tubercle with the anterior superior iliac spine (position of the inguinal ligament) and then continues along the iliac crest to the posterior superior iliac spine to separate the lower limb from the anterior and lateral abdominal walls;

passes between the posterior superior iliac spine and along the dorsolateral surface of the sacrum to the coccyx to separate the lower limb from the muscles of the back; and

passes between the posterior superior iliac spine and along the dorsolateral surface of the sacrum to the coccyx to separate the lower limb from the muscles of the back; and

joins the medial margin of the sacrotuberous ligament, the ischial tuberosity, the ischiopubic ramus, and the pubic symphysis to separate the lower limb from the perineum.

joins the medial margin of the sacrotuberous ligament, the ischial tuberosity, the ischiopubic ramus, and the pubic symphysis to separate the lower limb from the perineum.

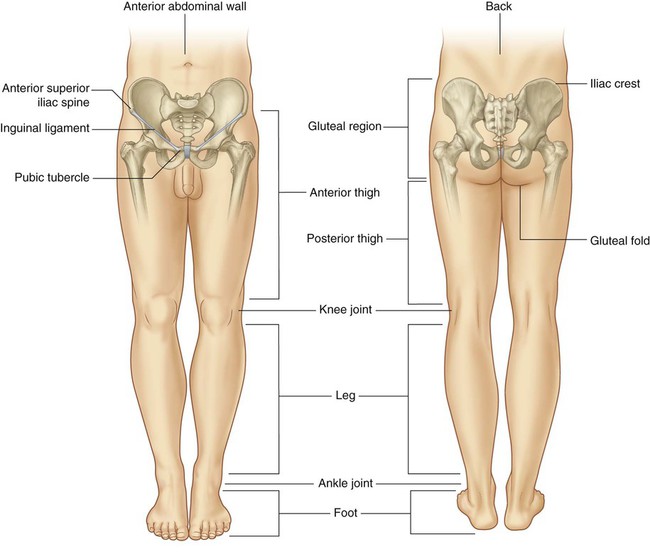

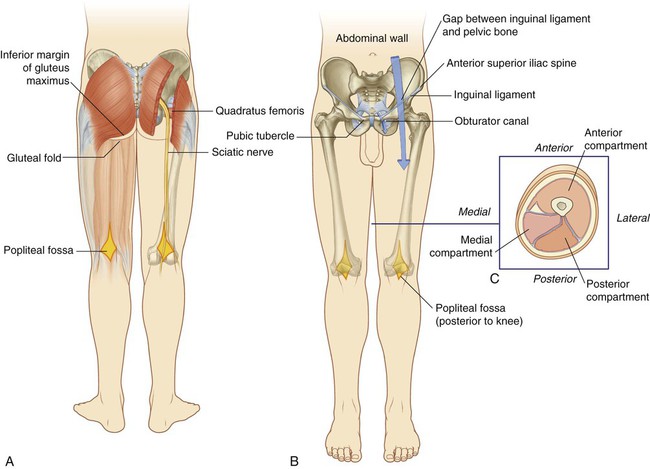

The lower limb is divided into the gluteal region, thigh, leg, and foot on the basis of major joints, component bones, and superficial landmarks (Fig. 6.2):

The gluteal region is posterolateral and between the iliac crest and the fold of skin (gluteal fold) that defines the lower limit of the buttocks.

The gluteal region is posterolateral and between the iliac crest and the fold of skin (gluteal fold) that defines the lower limit of the buttocks.

Anteriorly, the thigh is between the inguinal ligament and the knee joint—the hip joint is just inferior to the middle third of the inguinal ligament, and the posterior thigh is between the gluteal fold and the knee.

Anteriorly, the thigh is between the inguinal ligament and the knee joint—the hip joint is just inferior to the middle third of the inguinal ligament, and the posterior thigh is between the gluteal fold and the knee.

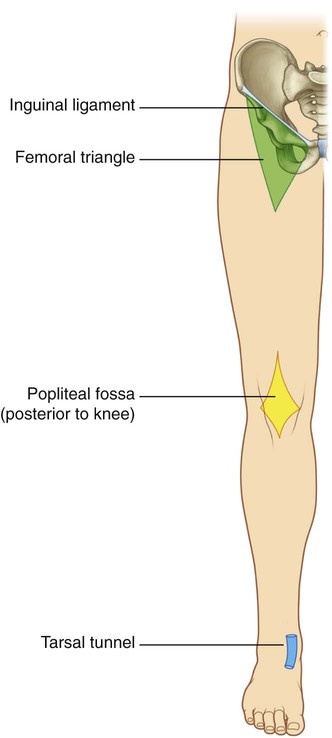

The femoral triangle and popliteal fossa, as well as the posteromedial side of the ankle, are important areas of transition through which structures pass between regions (Fig. 6.3).

Function

Support the body weight

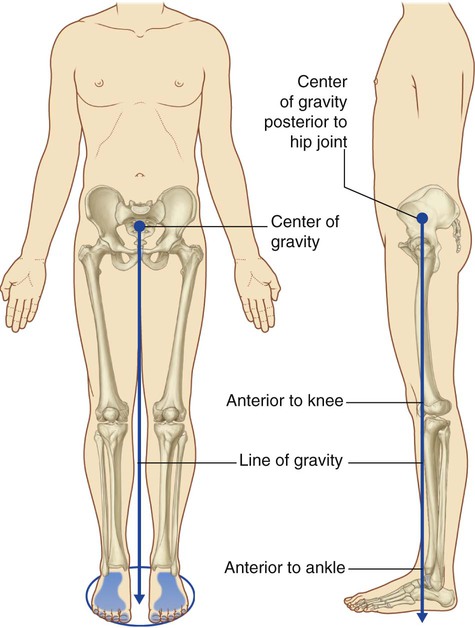

A major function of the lower limb is to support the weight of the body with minimal expenditure of energy. When standing erect, the center of gravity is anterior to the edge of the SII vertebra in the pelvis (Fig. 6.4). The vertical line through the center of gravity is slightly posterior to the hip joints, anterior to the knee and ankle joints, and directly over the almost circular support base formed by the feet on the ground and holds the knee and hip joints in extension.

Locomotion

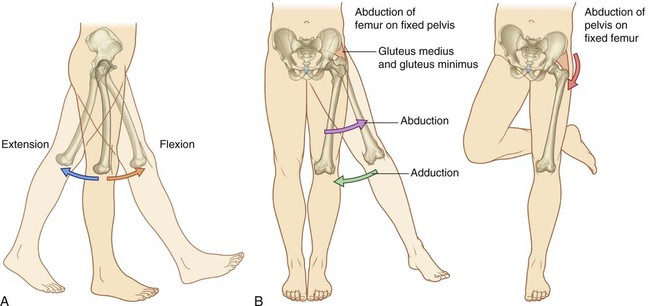

Movements at the hip joint are flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, medial and lateral rotation, and circumduction (Fig. 6.5).

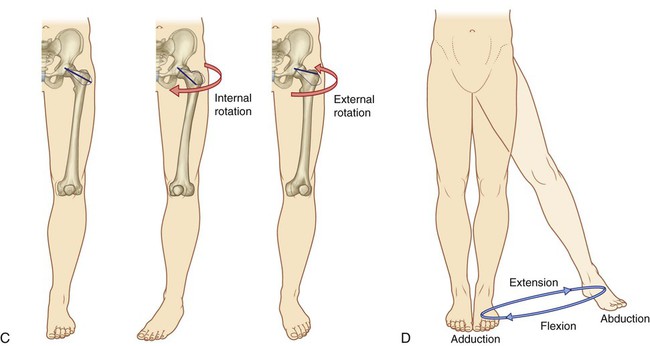

The knee and ankle joints are primarily hinge joints. Movements at the knee are mainly flexion and extension (Fig. 6.6A). Movements at the ankle are dorsiflexion (movement of the dorsal side of the foot toward the leg) and plantarflexion (Fig. 6.6B).

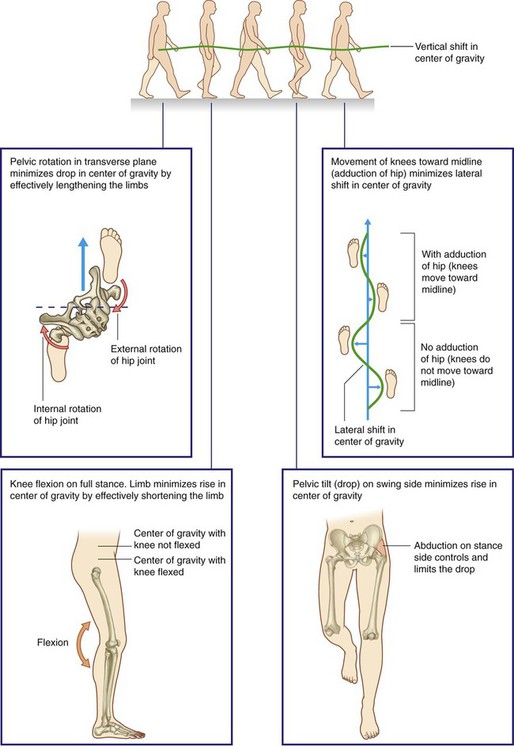

During walking, many anatomical features of the lower limbs contribute to minimizing fluctuations in the body’s center of gravity and thereby reduce the amount of energy needed to maintain locomotion and produce a smooth, efficient gait (Fig. 6.7). They include pelvic tilt in the coronal plane, pelvic rotation in the transverse plane, movement of the knees toward the midline, flexion of the knees, and complex interactions between the hip, knee, and ankle. As a result, during walking, the body’s center of gravity normally fluctuates only 5 cm in both vertical and lateral directions.

Component parts

Bones and joints

The bones of the gluteal region and the thigh are the pelvic bone and the femur (Fig. 6.8). The large ball and socket joint between these two bones is the hip joint.

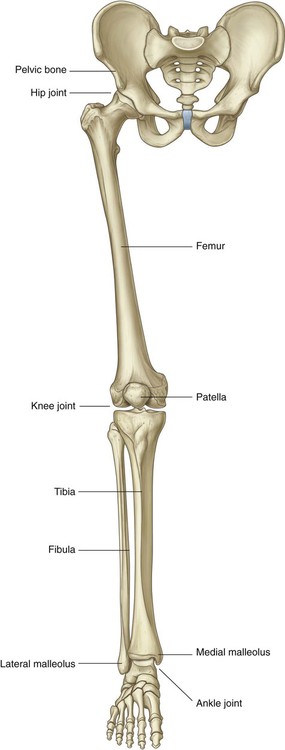

The tibia is medial in position, is larger than the laterally positioned fibula, and is the weight-bearing bone.

The tibia is medial in position, is larger than the laterally positioned fibula, and is the weight-bearing bone.

The fibula does not take part in the knee joint and forms only the most lateral part of the ankle joint—proximally, it forms a small synovial joint (superior tibiofibular joint) with the inferolateral surface of the head of the tibia.

The fibula does not take part in the knee joint and forms only the most lateral part of the ankle joint—proximally, it forms a small synovial joint (superior tibiofibular joint) with the inferolateral surface of the head of the tibia.

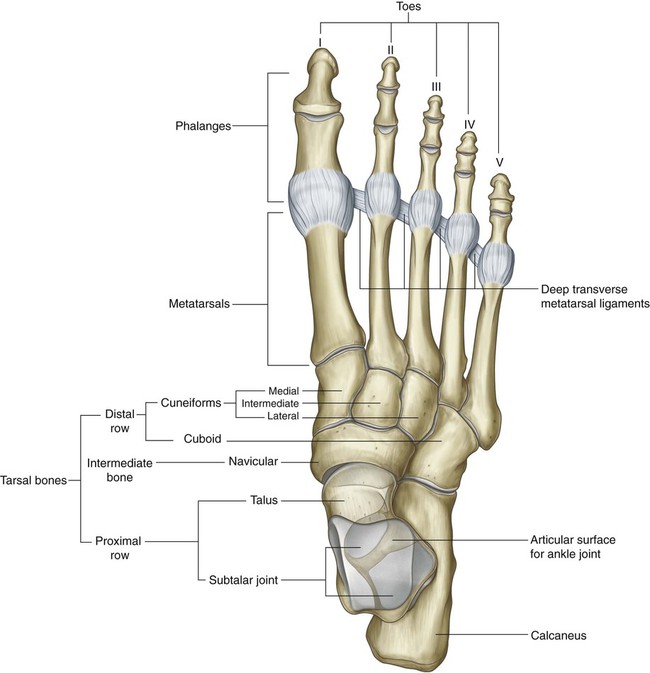

The bones of the foot consist of the tarsal bones, the metatarsals, and the phalanges (Fig. 6.9). There are seven tarsal bones, which are organized in two rows with an intermediate bone between the two rows on the medial side. Inversion and eversion of the foot, or turning the sole of the foot inward and outward, respectively, occur at joints between the tarsal bones.

The interphalangeal joints are hinge joints and allow flexion and extension.

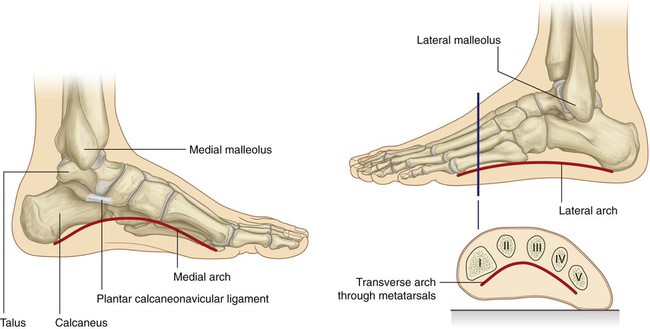

The bones of the foot are not organized in a single plane so that they lie flat on the ground. Rather, the metatarsals and tarsals form longitudinal and transverse arches (Fig. 6.10). The longitudinal arch is highest on the medial side of the foot. The arches are flexible in nature and are supported by muscles and ligaments. They absorb and transmit forces during walking and standing.

Muscles

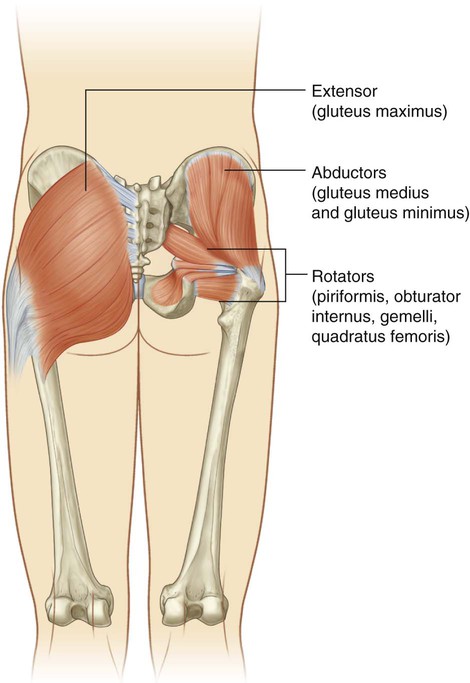

Muscles of the gluteal region consist predominantly of extensors, rotators, and abductors of the hip joint (Fig. 6.11). In addition to moving the thigh on a fixed pelvis, these muscles also control the movement of the pelvis relative to the limb bearing the body’s weight (weight-bearing or stance limb) while the other limb swings forward (swing limb) during walking.

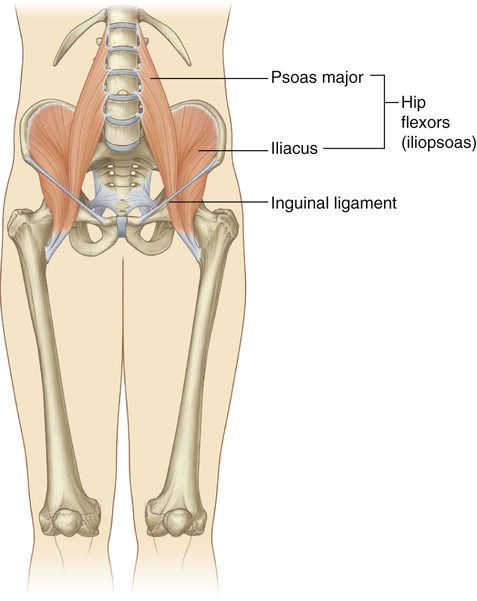

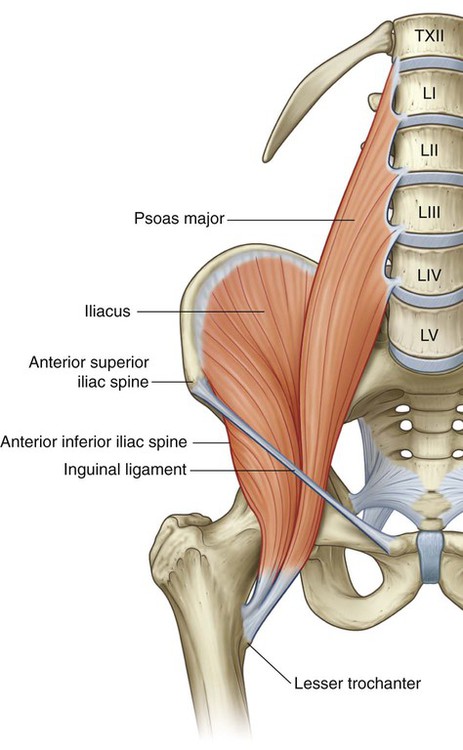

Major flexor muscles of the hip (iliopsoas—psoas major and iliacus) do not originate in the gluteal region or the thigh. Instead, they are attached to the posterior abdominal wall and descend through the gap between the inguinal ligament and pelvic bone to attach to the proximal end of the femur (Fig. 6.12).

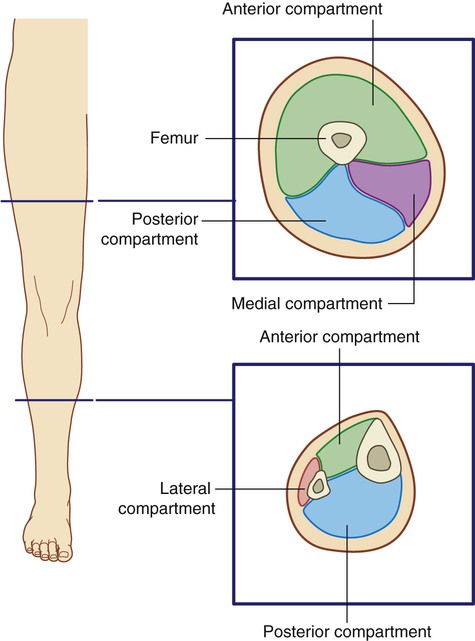

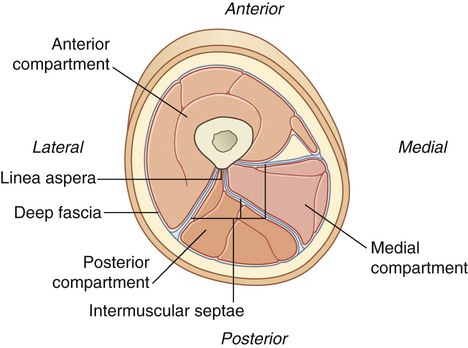

Muscles in the thigh and leg are separated into three compartments by layers of fascia, bones, and ligaments (Fig. 6.13).

In the thigh, there are medial (adductor), anterior (extensor), and posterior (flexor) compartments:

Most muscles in the medial compartment act mainly on the hip joint.

Most muscles in the medial compartment act mainly on the hip joint.

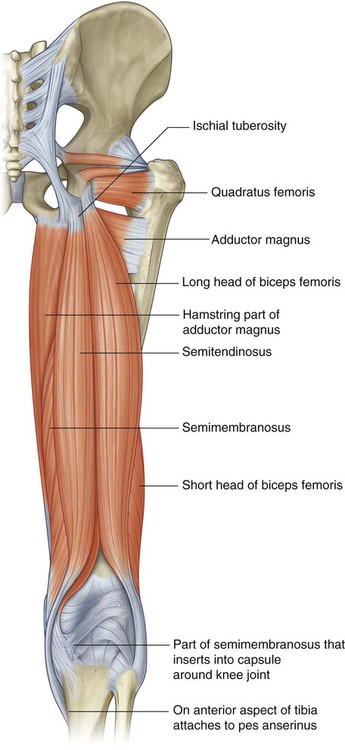

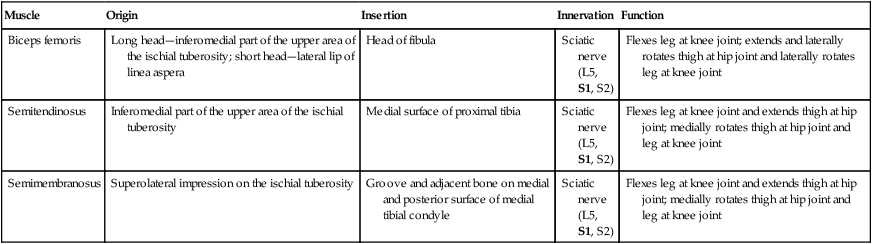

The large muscles (hamstrings) in the posterior compartment act on the hip (extension) and knee (flexion) because they attach to both the pelvis and bones of the leg.

The large muscles (hamstrings) in the posterior compartment act on the hip (extension) and knee (flexion) because they attach to both the pelvis and bones of the leg.

Muscles in the anterior compartment (quadriceps femoris) predominantly extend the knee.

Muscles in the anterior compartment (quadriceps femoris) predominantly extend the knee.

Muscles in the leg are divided into lateral (fibular), anterior, and posterior compartments:

Muscles in the lateral compartment predominantly evert the foot.

Muscles in the lateral compartment predominantly evert the foot.

Muscles in the anterior compartment dorsiflex the foot and extend the digits.

Muscles in the anterior compartment dorsiflex the foot and extend the digits.

Muscles in the posterior compartment plantarflex the foot and flex the digits; one of the muscles can also flex the knee because it attaches superiorly to the femur.

Muscles in the posterior compartment plantarflex the foot and flex the digits; one of the muscles can also flex the knee because it attaches superiorly to the femur.

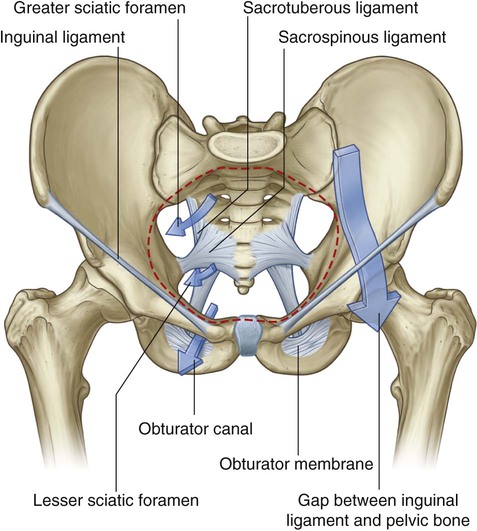

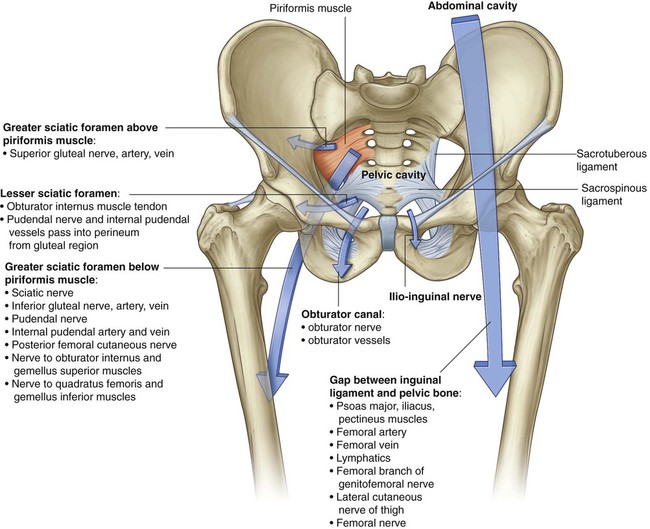

Relationship to other regions

Unlike in the upper limb where most structures pass between the neck and limb through a single axillary inlet, in the lower limb, there are four major entry and exit points between the lower limb and the abdomen, pelvis, and perineum (Fig. 6.14). These are:

the gap between the inguinal ligament and pelvic bone,

the gap between the inguinal ligament and pelvic bone,

the obturator canal (at the top of the obturator foramen), and

the obturator canal (at the top of the obturator foramen), and

Abdomen

The lower limb communicates directly with the abdomen through a gap between the pelvic bone and the inguinal ligament (Fig. 6.14). Structures passing though this gap include:

Key points

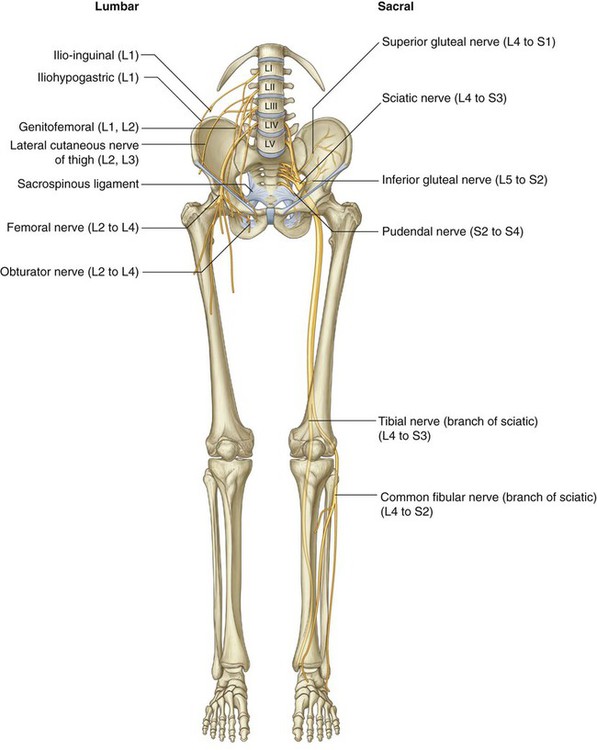

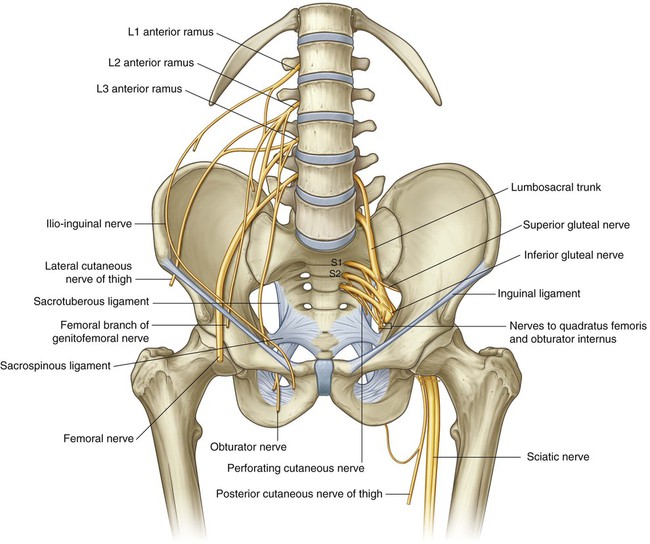

Innervation is by lumbar and sacral spinal nerves

Nerves originating from the lumbar and sacral plexuses and entering the lower limb carry fibers from spinal cord levels L1 to S3 (Fig. 6.15). Nerves from lower sacral segments innervate the perineum. Terminal nerves exit the abdomen and pelvis through a number of apertures and foramina and enter the limb. As a consequence of this innervation, lumbar and upper sacral nerves are tested clinically by examining the lower limb. In addition, clinical signs (such as pain, pins-and-needles sensations, paresthesia, and fascicular muscle twitching) resulting from any disorder affecting these spinal nerves (e.g., herniated intervertebral disc in the lumbar region) appear in the lower limb.

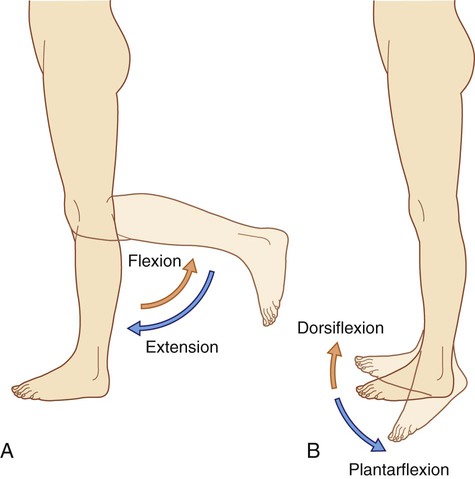

Dermatomes in the lower limb are shown in Fig. 6.16. Regions that can be tested for sensation and are reasonably autonomous (have minimal overlap) are:

over the inguinal ligament—L1,

over the inguinal ligament—L1,

lower medial side of the thigh—L3,

lower medial side of the thigh—L3,

The dermatomes of S4 and S5 are tested in the perineum.

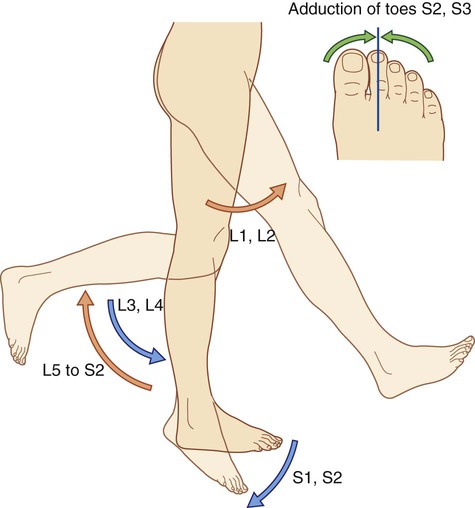

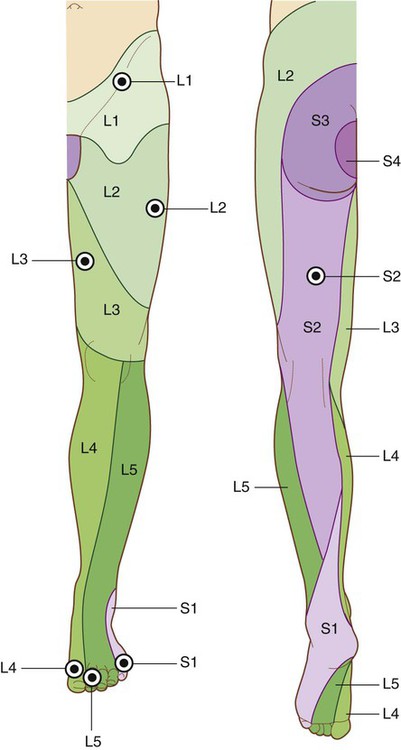

Selected joint movements are used to test myotomes (Fig. 6.17). For example:

Flexion of the hip is controlled primarily by L1 and L2.

Flexion of the hip is controlled primarily by L1 and L2.

Extension of the knee is controlled mainly by L3 and L4.

Extension of the knee is controlled mainly by L3 and L4.

Knee flexion is controlled mainly by L5 to S2.

Knee flexion is controlled mainly by L5 to S2.

Plantarflexion of the foot is controlled predominantly by S1 and S2.

Plantarflexion of the foot is controlled predominantly by S1 and S2.

A tap on the patellar ligament at the knee tests predominantly L3 and L4.

A tap on the patellar ligament at the knee tests predominantly L3 and L4.

A tendon tap on the calcaneal tendon posterior to the ankle (tendon of gastrocnemius and soleus) tests S1 and S2.

A tendon tap on the calcaneal tendon posterior to the ankle (tendon of gastrocnemius and soleus) tests S1 and S2.

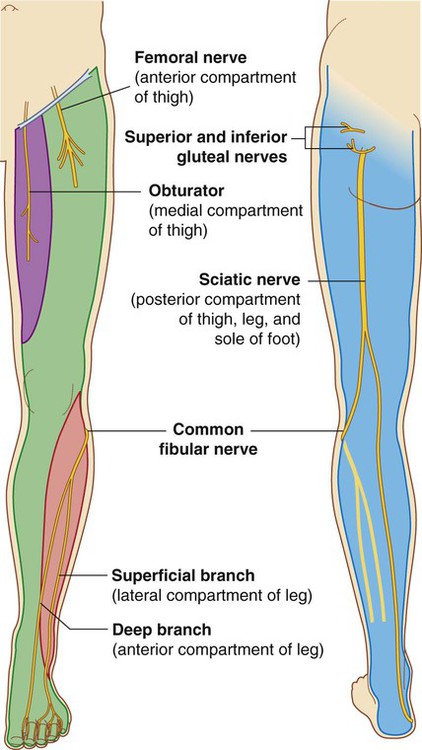

Each of the major muscle groups or compartments in the lower limb is innervated primarily by one or more of the major nerves that originate from the lumbar and sacral plexuses (Fig. 6.18):

Large muscles in the gluteal region are innervated by the superior and inferior gluteal nerves.

Large muscles in the gluteal region are innervated by the superior and inferior gluteal nerves.

Most muscles in the anterior compartment of the thigh are innervated by the femoral nerve (except the tensor fasciae latae, which are innervated by the superior gluteal nerve).

Most muscles in the anterior compartment of the thigh are innervated by the femoral nerve (except the tensor fasciae latae, which are innervated by the superior gluteal nerve).

Most muscles in the medial compartment are innervated mainly by the obturator nerve (except the pectineus, which is innervated by the femoral nerve, and part of the adductor magnus, which is innervated by the tibial division of the sciatic nerve).

Most muscles in the medial compartment are innervated mainly by the obturator nerve (except the pectineus, which is innervated by the femoral nerve, and part of the adductor magnus, which is innervated by the tibial division of the sciatic nerve).

Most muscles in the posterior compartment of the thigh and the leg and in the sole of the foot are innervated by the tibial part of the sciatic nerve (except the short head of the biceps femoris in the posterior thigh, which is innervated by the common fibular division of the sciatic nerve).

Most muscles in the posterior compartment of the thigh and the leg and in the sole of the foot are innervated by the tibial part of the sciatic nerve (except the short head of the biceps femoris in the posterior thigh, which is innervated by the common fibular division of the sciatic nerve).

The anterior and lateral compartments of the leg and muscles associated with the dorsal surface of the foot are innervated by the common fibular part of the sciatic nerve.

The anterior and lateral compartments of the leg and muscles associated with the dorsal surface of the foot are innervated by the common fibular part of the sciatic nerve.

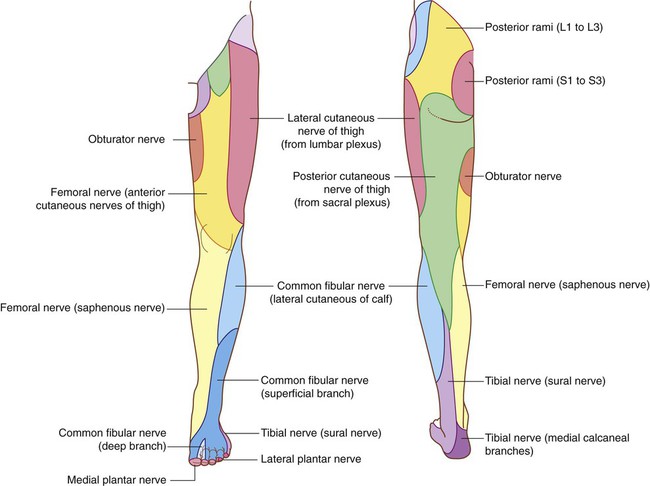

In addition to innervating major muscle groups, each of the major peripheral nerves originating from the lumbar and sacral plexuses carries general sensory information from patches of skin (Fig. 6.19). Sensation from these areas can be used to test for peripheral nerve lesions:

The femoral nerve innervates skin on the anterior thigh, medial side of the leg, and medial side of the ankle.

The femoral nerve innervates skin on the anterior thigh, medial side of the leg, and medial side of the ankle.

The obturator nerve innervates the medial side of the thigh.

The obturator nerve innervates the medial side of the thigh.

The tibial part of the sciatic nerve innervates the lateral side of the ankle and foot.

The tibial part of the sciatic nerve innervates the lateral side of the ankle and foot.

The common fibular nerve innervates the lateral side of the leg and the dorsum of the foot.

The common fibular nerve innervates the lateral side of the leg and the dorsum of the foot.

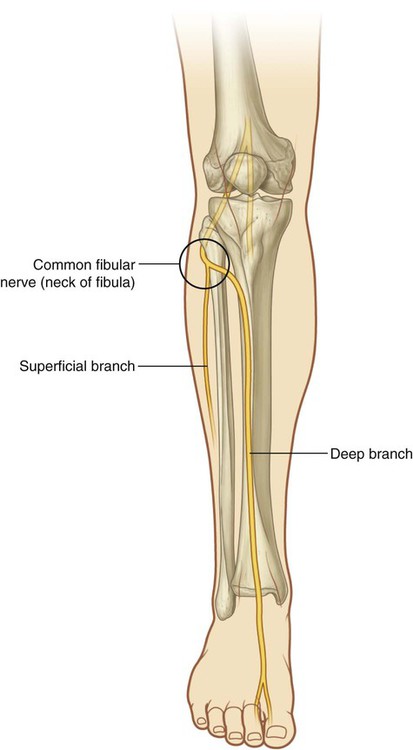

Nerves related to bone

The common fibular branch of the sciatic nerve curves laterally around the neck of the fibula when passing from the popliteal fossa into the leg (Fig. 6.20). The nerve can be rolled against bone just distal to the attachment of biceps femoris to the head of the fibula. In this location, the nerve can be damaged by impact injuries, fractures to the bone, or leg casts that are placed too high.

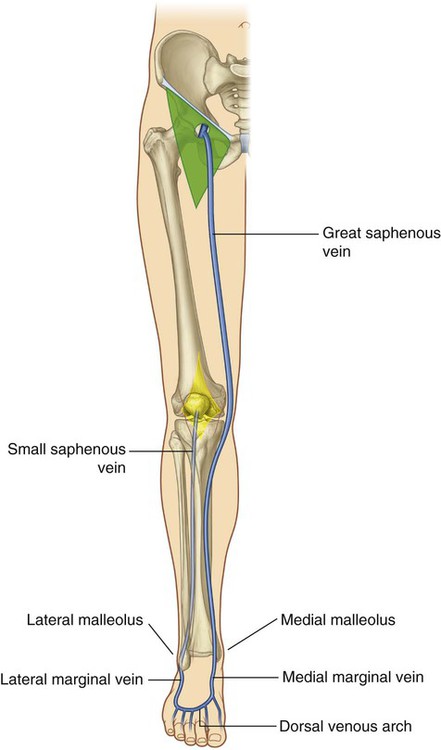

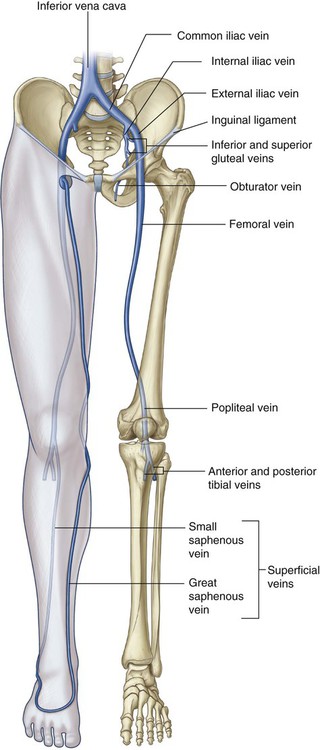

Superficial veins

Large veins embedded in the subcutaneous (superficial) fascia of the lower limb (Fig. 6.21) often become distended (varicose). These vessels can also be used for vascular transplantation.

The great saphenous vein passes up the medial side of the leg, knee, and thigh to pass through an opening in deep fascia covering the femoral triangle and join with the femoral vein.

The great saphenous vein passes up the medial side of the leg, knee, and thigh to pass through an opening in deep fascia covering the femoral triangle and join with the femoral vein.

The small saphenous vein passes behind the distal end of the fibula (lateral malleolus) and up the back of the leg to penetrate deep fascia and join the popliteal vein posterior to the knee.

The small saphenous vein passes behind the distal end of the fibula (lateral malleolus) and up the back of the leg to penetrate deep fascia and join the popliteal vein posterior to the knee.

Regional anatomy

Bony pelvis

The external surfaces of the pelvic bones, sacrum, and coccyx are predominantly the regions of the pelvis associated with the lower limb, although some muscles do originate from the deep or internal surfaces of these bones and from the deep surfaces of the lumbar vertebrae, above (Fig. 6.22).

Ilium

The inferior gluteal line originates just superior to the anterior inferior iliac spine and curves inferiorly across the bone to end near the posterior margin of the acetabulum—the rectus femoris muscle attaches to the anterior inferior iliac spine and to a roughened patch of bone between the superior margin of the acetabulum and the inferior gluteal line.

The inferior gluteal line originates just superior to the anterior inferior iliac spine and curves inferiorly across the bone to end near the posterior margin of the acetabulum—the rectus femoris muscle attaches to the anterior inferior iliac spine and to a roughened patch of bone between the superior margin of the acetabulum and the inferior gluteal line.

The anterior gluteal line originates from the lateral margin of the iliac crest between the anterior superior iliac spine and the tuberculum of the iliac crest, and arches inferiorly across the ilium to disappear just superior to the upper margin of the greater sciatic foramen—the gluteus minimus muscle originates from between the inferior and anterior gluteal lines.

The anterior gluteal line originates from the lateral margin of the iliac crest between the anterior superior iliac spine and the tuberculum of the iliac crest, and arches inferiorly across the ilium to disappear just superior to the upper margin of the greater sciatic foramen—the gluteus minimus muscle originates from between the inferior and anterior gluteal lines.

The posterior gluteal line descends almost vertically from the iliac crest to a position near the posterior inferior iliac spine—the gluteus medius muscle attaches to bone between the anterior and posterior gluteal lines, and the gluteus maximus muscle attaches posterior to the posterior gluteal line.

The posterior gluteal line descends almost vertically from the iliac crest to a position near the posterior inferior iliac spine—the gluteus medius muscle attaches to bone between the anterior and posterior gluteal lines, and the gluteus maximus muscle attaches posterior to the posterior gluteal line.

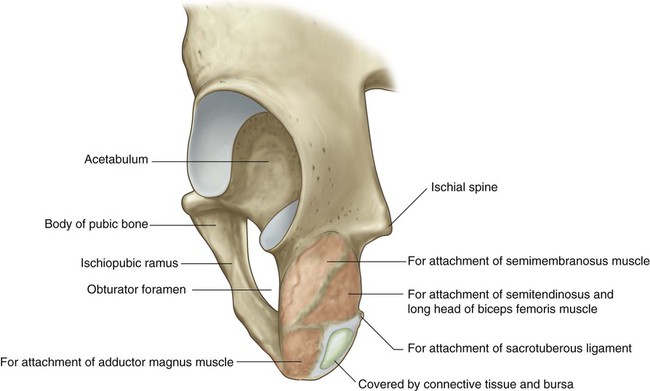

Ischial tuberosity

The ischial tuberosity is posteroinferior to the acetabulum and is associated mainly with the hamstring muscles of the posterior thigh (Fig. 6.23). It is divided into upper and lower areas by a transverse line.

The more medial part of the upper area is for the attachment of the combined origin of the semitendinosus muscle and the long head of the biceps femoris muscle.

The more medial part of the upper area is for the attachment of the combined origin of the semitendinosus muscle and the long head of the biceps femoris muscle.

The lateral part is for the attachment of the semimembranosus muscle.

The lateral part is for the attachment of the semimembranosus muscle.

The lateral region provides attachment for part of the adductor magnus muscle.

The lateral region provides attachment for part of the adductor magnus muscle.

The medial part faces inferiorly and is covered by connective tissue and by a bursa.

The medial part faces inferiorly and is covered by connective tissue and by a bursa.

Ischiopubic ramus and pubic bone

The external surfaces of the ischiopubic ramus anterior to the ischial tuberosity and the body of the pubis provide attachment for muscles of the medial compartment of the thigh (Fig. 6.23). These muscles include the adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, pectineus, and gracilis.

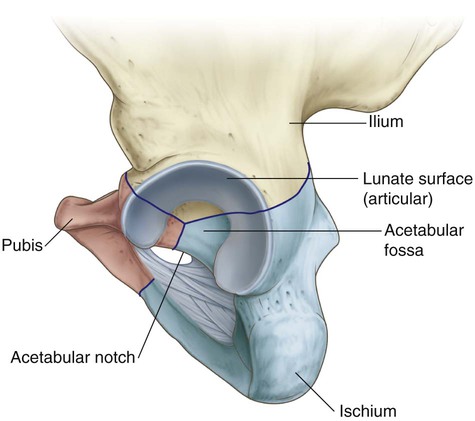

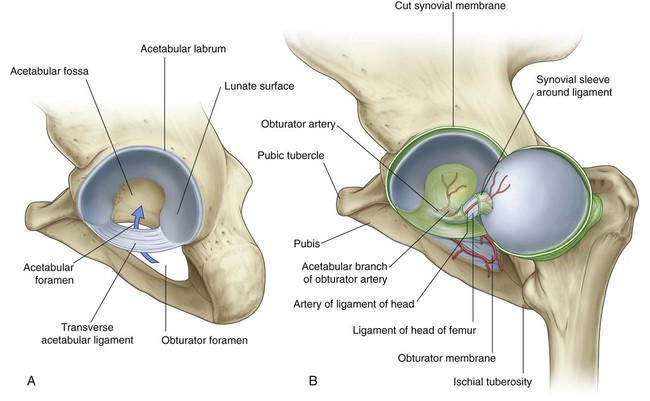

Acetabulum

The large cup-shaped acetabulum for articulation with the head of the femur is on the lateral surface of the pelvic bone in the region where the ilium, pubis, and ischium fuse (Fig. 6.24).

The margin of the acetabulum is marked inferiorly by a prominent notch (acetabular notch).

The wall of the acetabulum consists of nonarticular and articular parts:

The nonarticular part is rough and forms a shallow circular depression (the acetabular fossa) in central and inferior parts of the acetabular floor—the acetabular notch is continuous with the acetabular fossa.

The nonarticular part is rough and forms a shallow circular depression (the acetabular fossa) in central and inferior parts of the acetabular floor—the acetabular notch is continuous with the acetabular fossa.

The articular surface is broad and surrounds the anterior, superior, and posterior margins of the acetabular fossa.

The articular surface is broad and surrounds the anterior, superior, and posterior margins of the acetabular fossa.

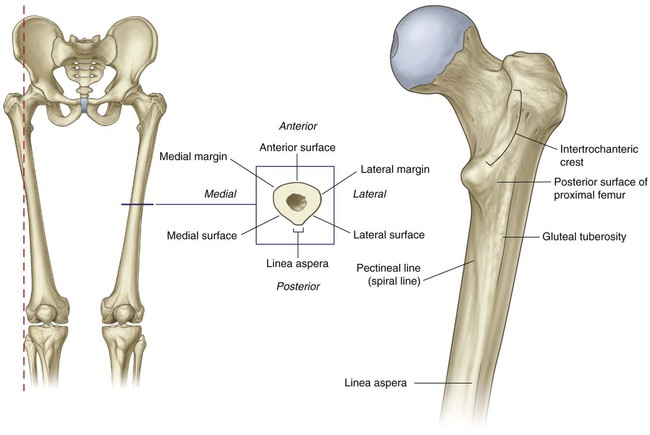

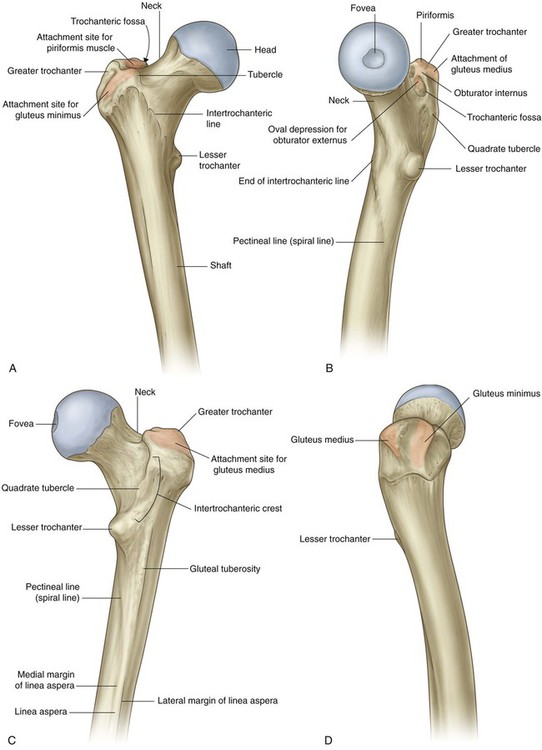

Proximal femur

The femur is the bone of the thigh and the longest bone in the body. Its proximal end is characterized by a head and neck, and two large projections (the greater and lesser trochanters) on the upper part of the shaft (Fig. 6.26).

Greater and lesser trochanters

The greater trochanter extends superiorly from the shaft of the femur just lateral to the region where the shaft joins the neck of the femur (Fig. 6.26). It continues posteriorly where its medial surface is deeply grooved to form the trochanteric fossa. The lateral wall of this fossa bears a distinct oval depression for attachment of the obturator externus muscle.

The lesser trochanter is smaller than the greater trochanter and has a blunt conical shape. It projects posteromedially from the shaft of the femur just inferior to the junction with the neck (Fig. 6.26). It is the attachment site for the combined tendons of psoas major and iliacus muscles.

Intertrochanteric line

The intertrochanteric line is a ridge of bone on the anterior surface of the upper margin of the shaft that descends medially from a tubercle on the anterior surface of the base of the greater trochanter to a position just anterior to the base of the lesser trochanter (Fig. 6.26). It is continuous with the pectineal line (spiral line), which curves medially under the lesser trochanter and around the shaft of the femur to merge with the medial margin of the linea aspera on the posterior aspect of the femur.

Intertrochanteric crest

The intertrochanteric crest is on the posterior surface of the femur and descends medially across the bone from the posterior margin of the greater trochanter to the base of the lesser trochanter (Fig. 6.26). It is a broad smooth ridge of bone with a prominent tubercle (the quadrate tubercle) on its upper half, which provides attachment for the quadratus femoris muscle.

Shaft of the femur

The shaft of the femur descends from lateral to medial in the coronal plane at an angle of 7° from the vertical axis (Fig. 6.27). The distal end of the femur is therefore closer to the midline than the upper end of the shaft.

The linea aspera is a major site of muscle attachment in the thigh. In the proximal third of the femur, the medial and lateral margins of the linea aspera diverge and continue superiorly as the pectineal line and gluteal tuberosity, respectively (Fig. 6.27):

The pectineal line curves anteriorly under the lesser trochanter and joins the intertrochanteric line.

The pectineal line curves anteriorly under the lesser trochanter and joins the intertrochanteric line.

The gluteal tuberosity is a broad linear roughening that curves laterally to the base of the greater trochanter.

The gluteal tuberosity is a broad linear roughening that curves laterally to the base of the greater trochanter.

The gluteus maximus muscle is attached to the gluteal tuberosity.

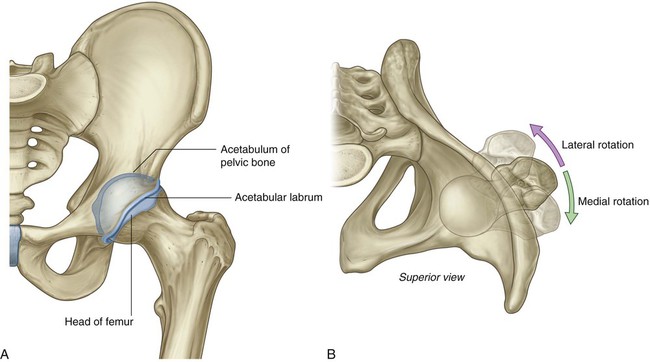

Hip joint

The hip joint is a synovial articulation between the head of the femur and the acetabulum of the pelvic bone (Fig. 6.29A). The joint is a multiaxial ball and socket joint designed for stability and weight-bearing at the expense of mobility. Movements at the joint include flexion, extension, abduction, adduction, medial and lateral rotation, and circumduction.

When considering the effects of muscle action on the hip joint, the long neck of the femur and the angulation of the neck on the shaft of the femur must be borne in mind. For example, medial and lateral rotation of the femur involves muscles that move the greater trochanter forward and backward, respectively, relative to the acetabulum (Fig. 6.29B).

The articular surfaces of the hip joint are:

Except for the fovea, the head of the femur is also covered by hyaline cartilage.

The rim of the acetabulum is raised slightly by a fibrocartilaginous collar (the acetabular labrum). Inferiorly, the labrum bridges across the acetabular notch as the transverse acetabular ligament and converts the notch into a foramen (Fig. 6.30A).

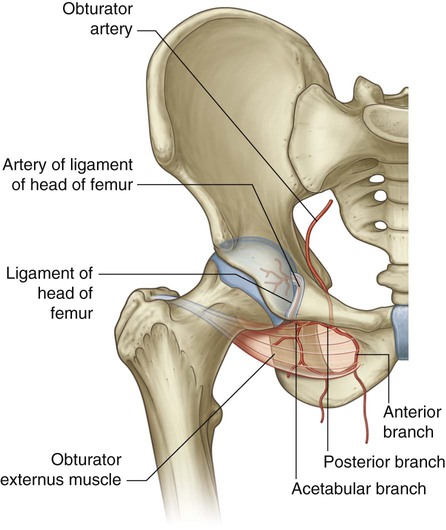

The ligament of the head of the femur is a flat band of delicate connective tissue that attaches at one end to the fovea on the head of the femur and at the other end to the acetabular fossa, transverse acetabular ligament, and margins of the acetabular notch (Fig. 6.30B). It carries a small branch of the obturator artery, which contributes to the blood supply of the head of the femur.

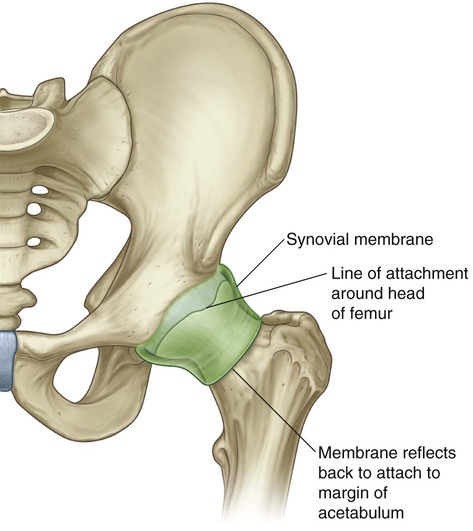

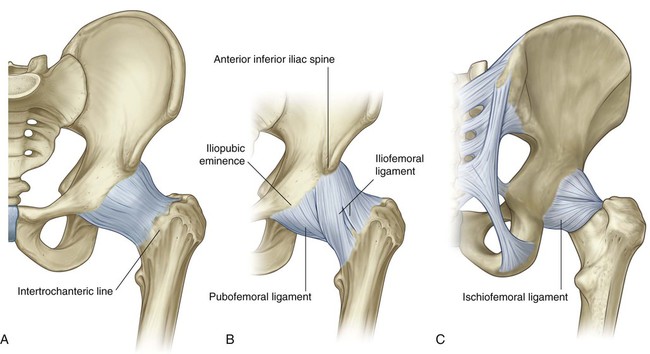

The synovial membrane attaches to the margins of the articular surfaces of the femur and acetabulum, forms a tubular covering around the ligament of the head of the femur, and lines the fibrous membrane of the joint (Figs. 6.30B and 6.31). From its attachment to the margin of the head of the femur, the synovial membrane covers the neck of the femur before reflecting onto the fibrous membrane (Fig. 6.31).

The fibrous membrane that encloses the hip joint is strong and generally thick. Medially, it is attached to the margin of the acetabulum, the transverse acetabular ligament, and the adjacent margin of the obturator foramen (Fig. 6.32A). Laterally, it is attached to the intertrochanteric line on the anterior aspect of the femur and to the neck of the femur just proximal to the intertrochanteric crest on the posterior surface.

Ligaments

The iliofemoral ligament is anterior to the hip joint and is triangular shaped (Fig. 6.32B). Its apex is attached to the ilium between the anterior inferior iliac spine and the margin of the acetabulum and its base is attached along the intertrochanteric line of the femur. Parts of the ligament attached above and below the intertrochanteric line are thicker than the part attached to the central part of the line. This results in the ligament having a Y appearance.

The iliofemoral ligament is anterior to the hip joint and is triangular shaped (Fig. 6.32B). Its apex is attached to the ilium between the anterior inferior iliac spine and the margin of the acetabulum and its base is attached along the intertrochanteric line of the femur. Parts of the ligament attached above and below the intertrochanteric line are thicker than the part attached to the central part of the line. This results in the ligament having a Y appearance.

The pubofemoral ligament is anteroinferior to the hip joint (Fig. 6.32B). It is also triangular in shape, with its base attached medially to the iliopubic eminence, adjacent bone, and obturator membrane. Laterally, it blends with the fibrous membrane and with the deep surface of the iliofemoral ligament.

The pubofemoral ligament is anteroinferior to the hip joint (Fig. 6.32B). It is also triangular in shape, with its base attached medially to the iliopubic eminence, adjacent bone, and obturator membrane. Laterally, it blends with the fibrous membrane and with the deep surface of the iliofemoral ligament.

The ischiofemoral ligament reinforces the posterior aspect of the fibrous membrane (Fig. 6.32C). It is attached medially to the ischium, just posteroinferior to the acetabulum, and laterally to the greater trochanter deep to the iliofemoral ligament.

The ischiofemoral ligament reinforces the posterior aspect of the fibrous membrane (Fig. 6.32C). It is attached medially to the ischium, just posteroinferior to the acetabulum, and laterally to the greater trochanter deep to the iliofemoral ligament.

Vascular supply to the hip joint is predominantly through branches of the obturator artery, medial and lateral circumflex femoral arteries, superior and inferior gluteal arteries, and the first perforating branch of the deep artery of the thigh. The articular branches of these vessels form a network around the joint (Fig. 6.33).

Gateways to the lower limb

There are four major routes by which structures pass from the abdomen and pelvis into and out of the lower limb. These are the obturator canal, the greater sciatic foramen, the lesser sciatic foramen, and the gap between the inguinal ligament and the anterosuperior margin of the pelvis (Fig. 6.34).

Obturator canal

The obturator canal is an almost vertically oriented passageway at the anterosuperior edge of the obturator foramen (Fig. 6.34). It is bordered:

above by a groove (obturator groove) on the inferior surface of the superior ramus of the pubic bone, and

above by a groove (obturator groove) on the inferior surface of the superior ramus of the pubic bone, and

below by the upper margin of the obturator membrane, which fills most of the obturator foramen, and by muscles (obturator internus and externus) attached to the inner and outer surfaces of the obturator membrane and surrounding bone.

below by the upper margin of the obturator membrane, which fills most of the obturator foramen, and by muscles (obturator internus and externus) attached to the inner and outer surfaces of the obturator membrane and surrounding bone.

Greater sciatic foramen

The greater sciatic foramen is formed on the posterolateral pelvic wall and is the major route for structures to pass between the pelvis and the gluteal region of the lower limb (Fig. 6.34). The margins of the foramen are formed by:

The superior gluteal nerve and vessels pass through the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis.

The superior gluteal nerve and vessels pass through the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis.

The sciatic nerve, inferior gluteal nerve and vessels, pudendal nerve and internal pudendal vessels, posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh, nerve to the obturator internus and gemellus superior, and nerve to the quadratus femoris and gemellus inferior pass through the greater sciatic foramen below the muscle.

The sciatic nerve, inferior gluteal nerve and vessels, pudendal nerve and internal pudendal vessels, posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh, nerve to the obturator internus and gemellus superior, and nerve to the quadratus femoris and gemellus inferior pass through the greater sciatic foramen below the muscle.

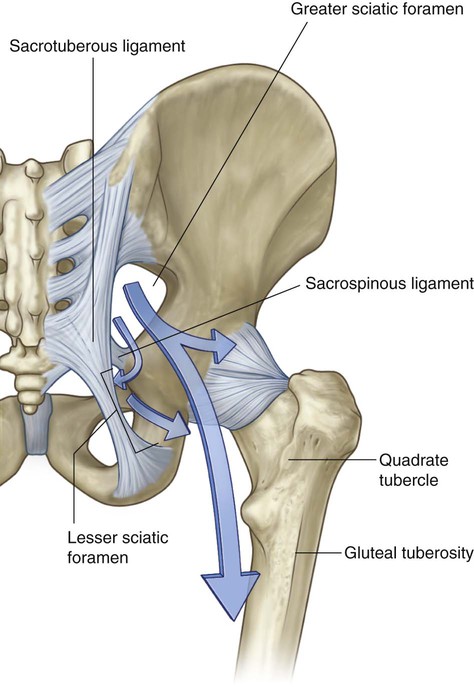

Lesser sciatic foramen

The lesser sciatic foramen is inferior to the greater sciatic foramen on the posterolateral pelvic wall (Fig. 6.34). It is also inferior to the lateral attachment of the pelvic floor (levator ani and coccygeus muscles) to the pelvic wall and therefore connects the gluteal region with the perineum:

The tendon of the obturator internus passes from the lateral pelvic wall through the lesser sciatic foramen into the gluteal region to insert on the femur.

The tendon of the obturator internus passes from the lateral pelvic wall through the lesser sciatic foramen into the gluteal region to insert on the femur.

The pudendal nerve and internal pudendal vessels, which first exit the pelvis by passing through the greater sciatic foramen below the piriformis muscle, enter the perineum below the pelvic floor by passing around the ischial spine and sacrospinous ligament and medially through the lesser sciatic foramen.

The pudendal nerve and internal pudendal vessels, which first exit the pelvis by passing through the greater sciatic foramen below the piriformis muscle, enter the perineum below the pelvic floor by passing around the ischial spine and sacrospinous ligament and medially through the lesser sciatic foramen.

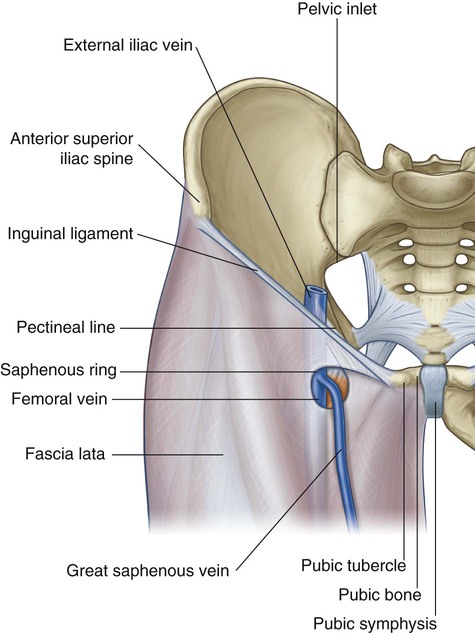

Gap between the inguinal ligament and pelvic bone

The large crescent-shaped gap between the inguinal ligament above and the anterosuperior margin of the pelvic bone below is the major route of communication between the abdomen and the anteromedial aspect of the thigh (Fig. 6.34). The psoas major, iliacus, and pectineus muscles pass through this gap to insert onto the femur. The major blood vessels (femoral artery and vein) and lymphatics of the lower limb also pass through it, as does the femoral nerve, to enter the femoral triangle of the thigh.

Nerves

Nerves that enter the lower limb from the abdomen and pelvis are terminal branches of the lumbosacral plexus on the posterior wall of the abdomen and the posterolateral walls of the pelvis (Fig. 6.35 and Table 6.1).

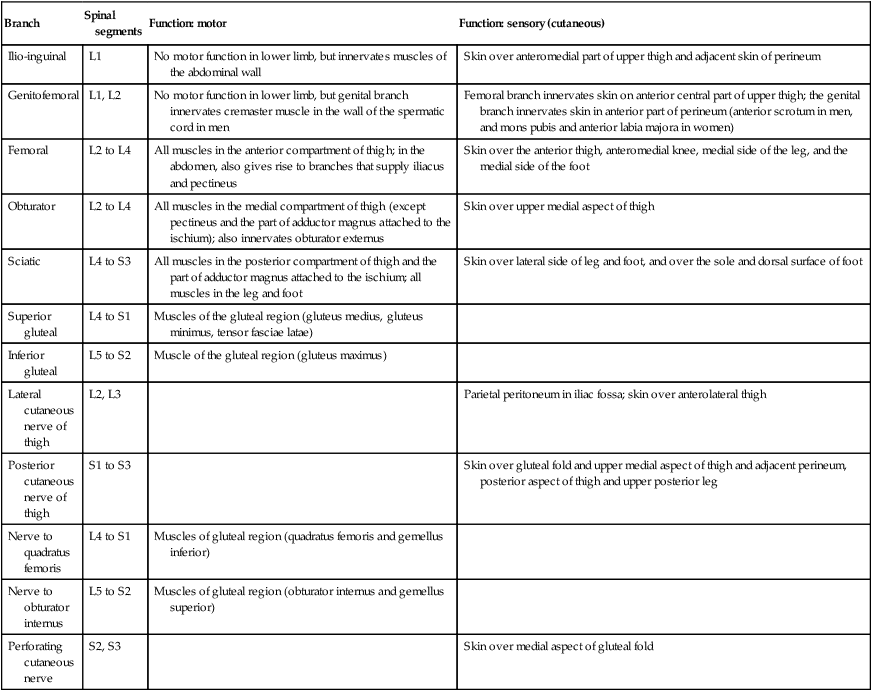

Table 6.1

Branches of the lumbosacral plexus associated with the lower limb

| Branch | Spinal segments | Function: motor | Function: sensory (cutaneous) |

| Ilio-inguinal | L1 | No motor function in lower limb, but innervates muscles of the abdominal wall | Skin over anteromedial part of upper thigh and adjacent skin of perineum |

| Genitofemoral | L1, L2 | No motor function in lower limb, but genital branch innervates cremaster muscle in the wall of the spermatic cord in men | Femoral branch innervates skin on anterior central part of upper thigh; the genital branch innervates skin in anterior part of perineum (anterior scrotum in men, and mons pubis and anterior labia majora in women) |

| Femoral | L2 to L4 | All muscles in the anterior compartment of thigh; in the abdomen, also gives rise to branches that supply iliacus and pectineus | Skin over the anterior thigh, anteromedial knee, medial side of the leg, and the medial side of the foot |

| Obturator | L2 to L4 | All muscles in the medial compartment of thigh (except pectineus and the part of adductor magnus attached to the ischium); also innervates obturator externus | Skin over upper medial aspect of thigh |

| Sciatic | L4 to S3 | All muscles in the posterior compartment of thigh and the part of adductor magnus attached to the ischium; all muscles in the leg and foot | Skin over lateral side of leg and foot, and over the sole and dorsal surface of foot |

| Superior gluteal | L4 to S1 | Muscles of the gluteal region (gluteus medius, gluteus minimus, tensor fasciae latae) | |

| Inferior gluteal | L5 to S2 | Muscle of the gluteal region (gluteus maximus) | |

| Lateral cutaneous nerve of thigh | L2, L3 | Parietal peritoneum in iliac fossa; skin over anterolateral thigh | |

| Posterior cutaneous nerve of thigh | S1 to S3 | Skin over gluteal fold and upper medial aspect of thigh and adjacent perineum, posterior aspect of thigh and upper posterior leg | |

| Nerve to quadratus femoris | L4 to S1 | Muscles of gluteal region (quadratus femoris and gemellus inferior) | |

| Nerve to obturator internus | L5 to S2 | Muscles of gluteal region (obturator internus and gemellus superior) | |

| Perforating cutaneous nerve | S2, S3 | Skin over medial aspect of gluteal fold |

The lumbar plexus is formed by the anterior rami of spinal nerves L1 to L3 and part of L4 (see Chapter 4, pp. 398–401). The rest of the anterior ramus of L4 and the anterior ramus of L5 combine to form the lumbosacral trunk, which enters the pelvic cavity and joins with the anterior rami of S1 to S3 and part of S4 to form the sacral plexus (see Chapter 5, pp. 486–492).

Femoral nerve

The femoral nerve carries contributions from the anterior rami of L2 to L4 and leaves the abdomen by passing through the gap between the inguinal ligament and superior margin of the pelvis to enter the femoral triangle on the anteromedial aspect of the thigh (Fig. 6.34 and Table 6.1). In the femoral triangle it is lateral to the femoral artery. The femoral nerve:

innervates all muscles in the anterior compartment of the thigh,

innervates all muscles in the anterior compartment of the thigh,

in the abdomen, gives rise to branches that innervate the iliacus and pectineus muscles, and

in the abdomen, gives rise to branches that innervate the iliacus and pectineus muscles, and

innervates skin over the anterior aspect of the thigh, the anteromedial side of the knee, the medial side of the leg, and the medial side of the foot.

innervates skin over the anterior aspect of the thigh, the anteromedial side of the knee, the medial side of the leg, and the medial side of the foot.

Obturator nerve

The obturator nerve, like the femoral nerve, originates from L2 to L4. It descends along the posterior abdominal wall, passes through the pelvic cavity and enters the thigh by passing through the obturator canal (Fig. 6.35 and Table 6.1). The obturator nerve innervates:

Sciatic nerve

The sciatic nerve is the largest nerve of the body and carries contributions from L4 to S3. It leaves the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle, enters and passes through the gluteal region (Fig. 6.35 and Table 6.1), and then enters the posterior compartment of the thigh where it divides into its two major branches:

Gluteal nerves

The gluteal nerves are major motor nerves of the gluteal region.

The superior gluteal nerve (Fig. 6.35 and Table 6.1) carries contributions from the anterior rami of L4 to S1, leaves the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle, and innervates:

The inferior gluteal nerve (Fig. 6.35 and Table 6.1) is formed by contributions from L5 to S2, leaves the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle, and enters the gluteal region to supply the gluteus maximus.

Ilio-inguinal and genitofemoral nerves

The ilio-inguinal nerve originates from the superior part of the lumbar plexus, descends around the abdominal wall in the plane between the transversus abdominis and internal oblique muscles, and then passes through the inguinal canal to leave the abdominal wall through the superficial inguinal ring (Fig. 6.35 and Table 6.1). Its terminal branches innervate skin on the medial side of the upper thigh and adjacent parts of the perineum.

The genitofemoral nerve passes anteroinferiorly through the psoas major muscle on the posterior abdominal wall and descends on the anterior surface of the psoas major (Fig. 6.35 and Table 6.1). Its femoral branch passes into the thigh by crossing under the inguinal ligament where it is lateral to the femoral artery. It passes superficially to innervate skin over the upper central part of the anterior thigh.

Lateral cutaneous nerve of thigh

The lateral cutaneous nerve of the thigh originates from L2 and L3. It leaves the abdomen either by passing through the gap between the inguinal ligament and the pelvic bone just medial to the anterior superior iliac spine or by passing directly through the inguinal ligament (Fig. 6.35 and Table 6.1). It supplies skin on the lateral side of the thigh.

Nerve to quadratus femoris and nerve to obturator internus

The nerve to the quadratus femoris (L4 to S1) and the nerve to the obturator internus (L5 to S2) are small motor nerves that originate from the sacral plexus. Both nerves pass through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle and enter the gluteal region (Fig. 6.35 and Table 6.1):

The nerve to the obturator internus supplies the gemellus superior muscle in the gluteal region and then loops around the ischial spine and enters the perineum through the lesser sciatic foramen to penetrate the perineal surface of the obturator internus muscle.

The nerve to the obturator internus supplies the gemellus superior muscle in the gluteal region and then loops around the ischial spine and enters the perineum through the lesser sciatic foramen to penetrate the perineal surface of the obturator internus muscle.

The nerve to the quadratus femoris supplies the gemellus inferior and quadratus femoris muscles.

The nerve to the quadratus femoris supplies the gemellus inferior and quadratus femoris muscles.

Posterior cutaneous nerve of thigh

The posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh is formed by contributions from S1 to S3 and leaves the pelvic cavity through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle (Fig. 6.35 and Table 6.1). It passes vertically through the gluteal region deep to the gluteus maximus and enters the posterior thigh and innervates:

Perforating cutaneous nerve

The perforating cutaneous nerve is a small sensory nerve formed by contributions from S2 and S3. It leaves the pelvic cavity by penetrating directly through the sacrotuberous ligament (Fig. 6.35 and Table 6.1) and passes inferiorly around the lower border of the gluteus maximus where it overlaps with the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh in innervating skin over the medial aspect of the gluteal fold.

Arteries

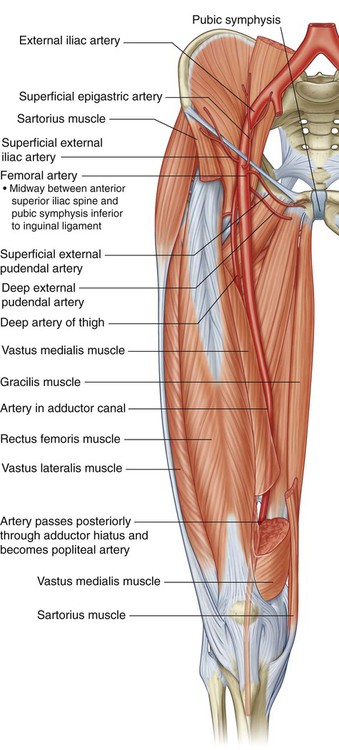

Femoral artery

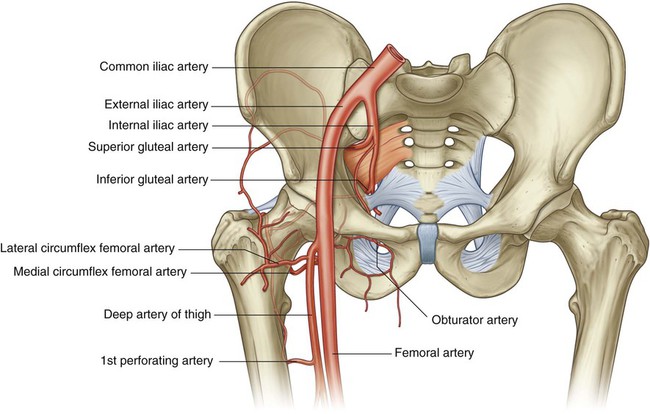

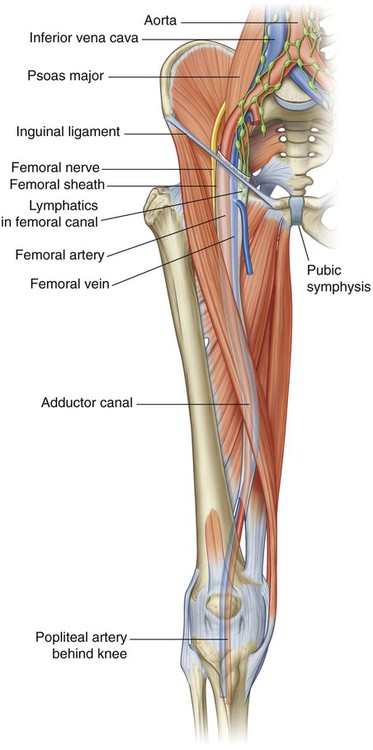

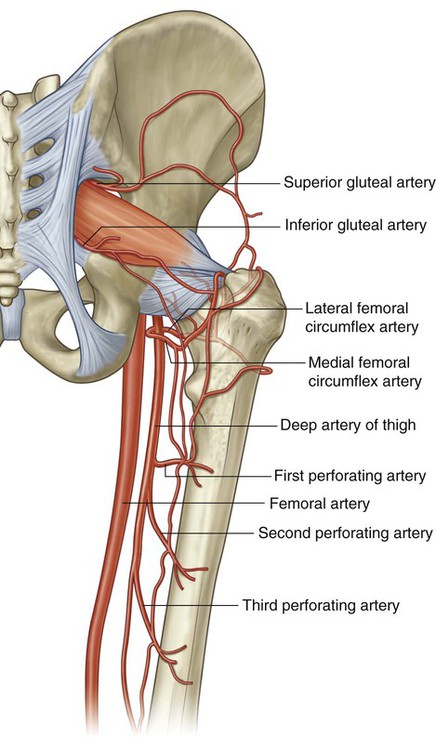

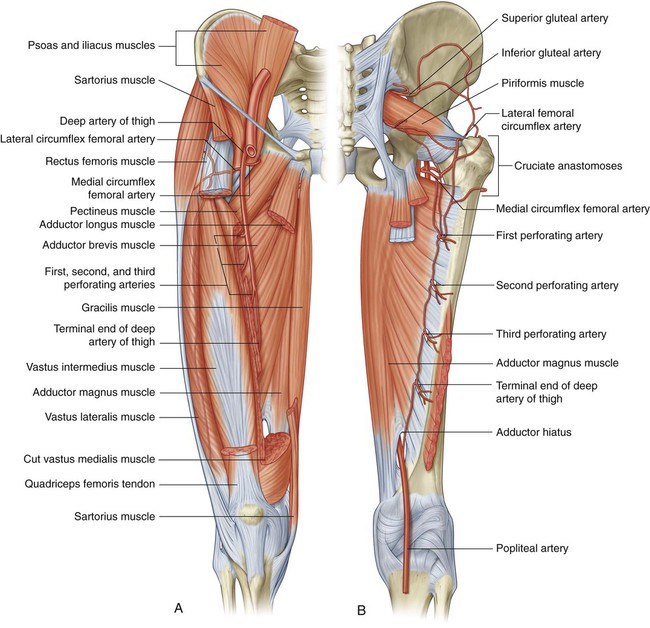

The major artery supplying the lower limb is the femoral artery (Fig. 6.36), which is the continuation of the external iliac artery in the abdomen. The external iliac artery becomes the femoral artery as the vessel passes under the inguinal ligament to enter the femoral triangle in the anterior aspect of the thigh. Branches supply most of the thigh and all of the leg and foot.

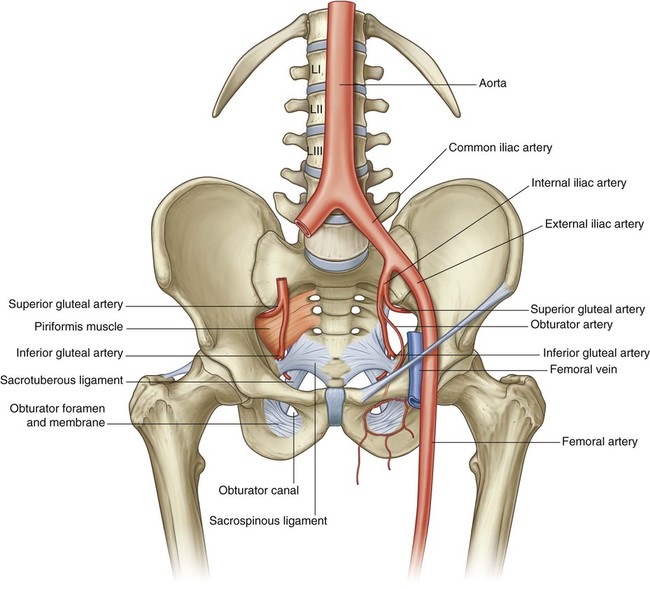

Superior and inferior gluteal arteries and the obturator artery

Other vessels supplying parts of the lower limb include the superior and inferior gluteal arteries and the obturator artery (Fig. 6.36).

The superior and inferior gluteal arteries originate in the pelvic cavity as branches of the internal iliac artery (see Chapter 5, pp. 495–498) and supply the gluteal region. The superior gluteal artery leaves the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle, and the inferior gluteal artery leaves through the same foramen but below the piriformis muscle.

The obturator artery is also a branch of the internal iliac artery in the pelvic cavity (see Chapter 5, pp. 496–497) and passes through the obturator canal to enter and supply the medial compartment of the thigh.

Veins

Veins draining the lower limb form superficial and deep groups.

The deep veins generally follow the arteries (femoral, superior gluteal, inferior gluteal, and obturator). The major deep vein draining the limb is the femoral vein (Fig. 6.37). It becomes the external iliac vein when it passes under the inguinal ligament to enter the abdomen.

The great saphenous vein originates from the medial side of the dorsal venous arch and then ascends up the medial side of the leg, knee, and thigh to connect with the femoral vein just inferior to the inguinal ligament.

The great saphenous vein originates from the medial side of the dorsal venous arch and then ascends up the medial side of the leg, knee, and thigh to connect with the femoral vein just inferior to the inguinal ligament.

The small saphenous vein originates from the lateral side of the dorsal venous arch, ascends up the posterior surface of the leg, and then penetrates deep fascia to join the popliteal vein posterior to the knee; proximal to the knee, the popliteal vein becomes the femoral vein.

The small saphenous vein originates from the lateral side of the dorsal venous arch, ascends up the posterior surface of the leg, and then penetrates deep fascia to join the popliteal vein posterior to the knee; proximal to the knee, the popliteal vein becomes the femoral vein.

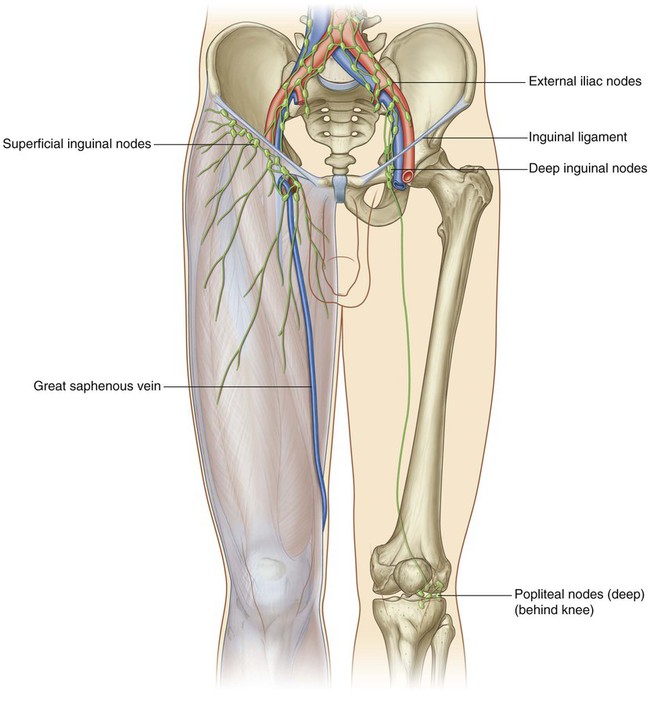

Lymphatics

Most lymphatic vessels in the lower limb drain into superficial and deep inguinal nodes located in the fascia just inferior to the inguinal ligament (Fig. 6.38).

Popliteal nodes

In addition to the inguinal nodes, there is a small collection of deep nodes posterior to the knee close to the popliteal vessels (Fig. 6.38). These popliteal nodes receive lymph from superficial vessels, which accompany the small saphenous vein, and from deep areas of the leg and foot. They ultimately drain into the deep and superficial inguinal nodes.

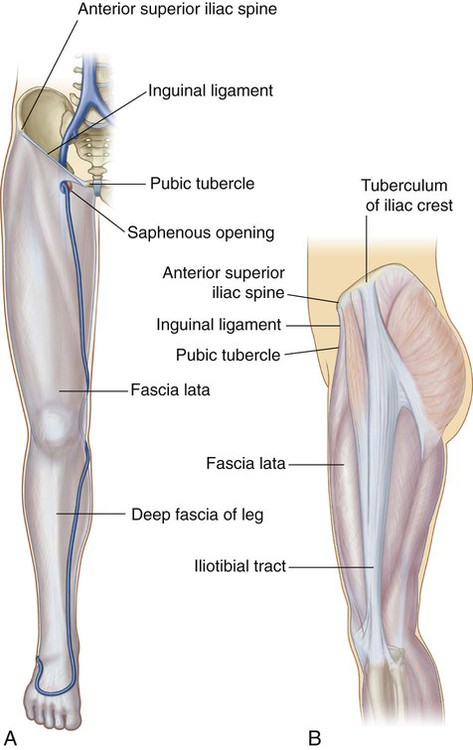

Deep fascia and the saphenous opening

Fascia lata

The outer layer of deep fascia in the lower limb forms a thick “stocking-like” membrane, which covers the limb and lies beneath the superficial fascia (Fig. 6.39A). This deep fascia is particularly thick in the thigh and gluteal region and is termed the fascia lata.

Inferiorly, the fascia lata is continuous with the deep fascia of the leg.

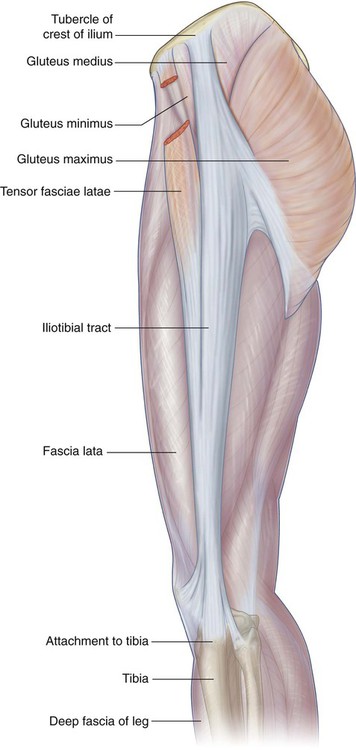

Iliotibial tract

The fascia lata is thickened laterally into a longitudinal band (the iliotibial tract), which descends along the lateral margin of the limb from the tuberculum of the iliac crest to a bony attachment just below the knee (Fig. 6.39B).

Saphenous opening

The fascia lata has one prominent aperture on the anterior aspect of the thigh just inferior to the medial end of the inguinal ligament (the saphenous opening), which allows the great saphenous vein to pass from superficial fascia through the deep fascia to connect with the femoral vein (Fig. 6.40).

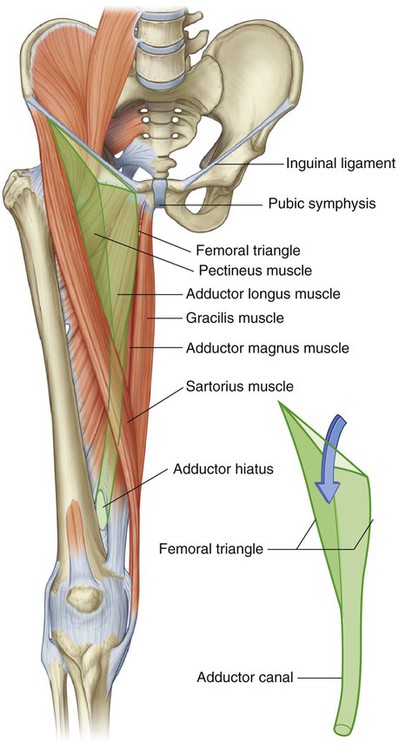

Femoral triangle

The femoral triangle is a wedge-shaped depression formed by muscles in the upper thigh at the junction between the anterior abdominal wall and the lower limb (Fig. 6.41):

The base of the triangle is the inguinal ligament.

The base of the triangle is the inguinal ligament.

The medial border is the medial margin of the adductor longus muscle in the medial compartment of the thigh.

The medial border is the medial margin of the adductor longus muscle in the medial compartment of the thigh.

The lateral margin is the medial margin of the sartorius muscle in the anterior compartment of the thigh.

The lateral margin is the medial margin of the sartorius muscle in the anterior compartment of the thigh.

The floor of the triangle is formed medially by the pectineus and adductor longus muscles in the medial compartment of the thigh and laterally by the iliopsoas muscle descending from the abdomen.

The floor of the triangle is formed medially by the pectineus and adductor longus muscles in the medial compartment of the thigh and laterally by the iliopsoas muscle descending from the abdomen.

The apex of the femoral triangle points inferiorly and is continuous with a fascial canal (adductor canal), which descends medially down the thigh and posteriorly through an aperture in the lower end of one of the largest of the adductor muscles in the thigh (the adductor magnus muscle) to open into the popliteal fossa behind the knee.

The apex of the femoral triangle points inferiorly and is continuous with a fascial canal (adductor canal), which descends medially down the thigh and posteriorly through an aperture in the lower end of one of the largest of the adductor muscles in the thigh (the adductor magnus muscle) to open into the popliteal fossa behind the knee.

The femoral nerve, artery, and vein and lymphatics pass between the abdomen and lower limb under the inguinal ligament and in the femoral triangle (Fig. 6.42). The femoral artery and vein pass inferiorly through the adductor canal and become the popliteal vessels behind the knee where they meet and are distributed with branches of the sciatic nerve, which descends through the posterior thigh from the gluteal region.

Gluteal region

The gluteal region lies posterolateral to the bony pelvis and proximal end of the femur (Fig. 6.43). Muscles in the region mainly abduct, extend, and laterally rotate the femur relative to the pelvic bone.

Muscles

Muscles of the gluteal region (Table 6.2) are composed mainly of two groups:

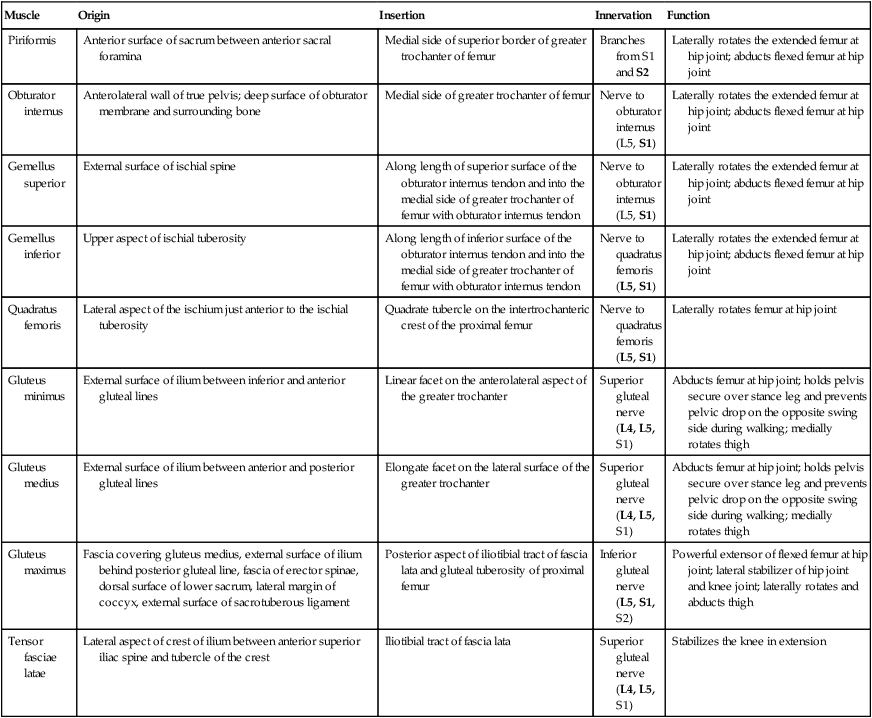

Table 6.2

Muscles of the gluteal region (spinal segments in bold are the major segments innervating the muscle)

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Function |

| Piriformis | Anterior surface of sacrum between anterior sacral foramina | Medial side of superior border of greater trochanter of femur | Branches from S1 and S2 | Laterally rotates the extended femur at hip joint; abducts flexed femur at hip joint |

| Obturator internus | Anterolateral wall of true pelvis; deep surface of obturator membrane and surrounding bone | Medial side of greater trochanter of femur | Nerve to obturator internus (L5, S1) | Laterally rotates the extended femur at hip joint; abducts flexed femur at hip joint |

| Gemellus superior | External surface of ischial spine | Along length of superior surface of the obturator internus tendon and into the medial side of greater trochanter of femur with obturator internus tendon | Nerve to obturator internus (L5, S1) | Laterally rotates the extended femur at hip joint; abducts flexed femur at hip joint |

| Gemellus inferior | Upper aspect of ischial tuberosity | Along length of inferior surface of the obturator internus tendon and into the medial side of greater trochanter of femur with obturator internus tendon | Nerve to quadratus femoris (L5, S1) | Laterally rotates the extended femur at hip joint; abducts flexed femur at hip joint |

| Quadratus femoris | Lateral aspect of the ischium just anterior to the ischial tuberosity | Quadrate tubercle on the intertrochanteric crest of the proximal femur | Nerve to quadratus femoris (L5, S1) | Laterally rotates femur at hip joint |

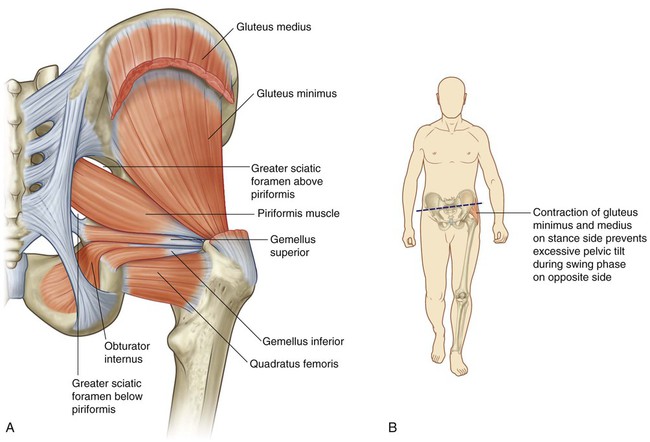

| Gluteus minimus | External surface of ilium between inferior and anterior gluteal lines | Linear facet on the anterolateral aspect of the greater trochanter | Superior gluteal nerve (L4, L5, S1) | Abducts femur at hip joint; holds pelvis secure over stance leg and prevents pelvic drop on the opposite swing side during walking; medially rotates thigh |

| Gluteus medius | External surface of ilium between anterior and posterior gluteal lines | Elongate facet on the lateral surface of the greater trochanter | Superior gluteal nerve (L4, L5, S1) | Abducts femur at hip joint; holds pelvis secure over stance leg and prevents pelvic drop on the opposite swing side during walking; medially rotates thigh |

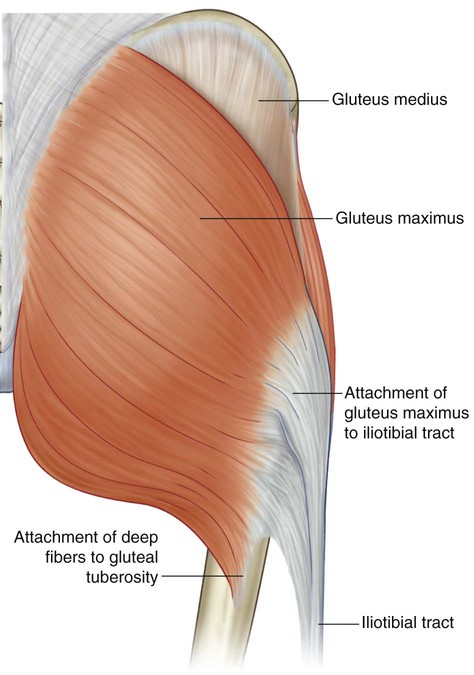

| Gluteus maximus | Fascia covering gluteus medius, external surface of ilium behind posterior gluteal line, fascia of erector spinae, dorsal surface of lower sacrum, lateral margin of coccyx, external surface of sacrotuberous ligament | Posterior aspect of iliotibial tract of fascia lata and gluteal tuberosity of proximal femur | Inferior gluteal nerve (L5, S1, S2) | Powerful extensor of flexed femur at hip joint; lateral stabilizer of hip joint and knee joint; laterally rotates and abducts thigh |

| Tensor fasciae latae | Lateral aspect of crest of ilium between anterior superior iliac spine and tubercle of the crest | Iliotibial tract of fascia lata | Superior gluteal nerve (L4, L5, S1) | Stabilizes the knee in extension |

a deep group of small muscles, which are mainly lateral rotators of the femur at the hip joint and include the piriformis, obturator internus, gemellus superior, gemellus inferior, and quadratus femoris;

a deep group of small muscles, which are mainly lateral rotators of the femur at the hip joint and include the piriformis, obturator internus, gemellus superior, gemellus inferior, and quadratus femoris;

a more superficial group of larger muscles, which mainly abduct and extend the hip and include the gluteus minimus, gluteus medius, and gluteus maximus; an additional muscle in this group, the tensor fasciae latae, stabilizes the knee in extension by acting on a specialized longitudinal band of deep fascia (the iliotibial tract) that passes down the lateral side of the thigh to attach to the proximal end of the tibia in the leg.

a more superficial group of larger muscles, which mainly abduct and extend the hip and include the gluteus minimus, gluteus medius, and gluteus maximus; an additional muscle in this group, the tensor fasciae latae, stabilizes the knee in extension by acting on a specialized longitudinal band of deep fascia (the iliotibial tract) that passes down the lateral side of the thigh to attach to the proximal end of the tibia in the leg.

Deep group

Piriformis

The piriformis muscle is the most superior of the deep group of muscles (Fig. 6.44) and is a muscle of the pelvic wall and of the gluteal region (see Chapter 5, p. 451). It originates from between the anterior sacral foramina on the anterolateral surface of the sacrum and passes laterally and inferiorly through the greater sciatic foramen.

The piriformis externally rotates and abducts the femur at the hip joint and is innervated in the pelvic cavity by the nerve to the piriformis, which originates as branches from S1 and S2 of the sacral plexus (see Chapter 5, p. 487).

Obturator internus

The obturator internus muscle, like the piriformis muscle, is a muscle of the pelvic wall and of the gluteal region (Fig. 6.44). It is a flat fan-shaped muscle originating from the medial surface of the obturator membrane and adjacent bone of the obturator foramen (see Chapter 5, pp. 450–451). Because the pelvic floor attaches to a thickened band of fascia across the medial surface of the obturator internus, the obturator internus forms:

Gemellus superior and inferior

The gemellus superior and inferior (gemelli is Latin for “twins”) are a pair of triangular muscles associated with the upper and lower margins of the obturator internus tendon (Fig. 6.44):

Superficial group

Gluteus minimus and medius

The gluteus minimus and medius muscles are two muscles of the more superficial group in the gluteal region (Fig. 6.44).

The gluteus medius and minimus muscles abduct the lower limb at the hip joint and reduce pelvic drop over the opposite swing limb during walking by securing the position of the pelvis on the stance limb (Fig. 6.44B). Both muscles are innervated by the superior gluteal nerve.

Tensor fasciae latae

The tensor fasciae latae muscle is the most anterior of the superficial group of muscles in the gluteal region and overlies the gluteus minimus and the anterior part of the gluteus medius (Fig. 6.46).

The tensor fasciae latae stabilizes the knee in extension and, working with the gluteus maximus muscle on the iliotibial tract lateral to the greater trochanter, stabilizes the hip joint by holding the head of the femur in the acetabulum (Fig. 6.46). It is innervated by the superior gluteal nerve.

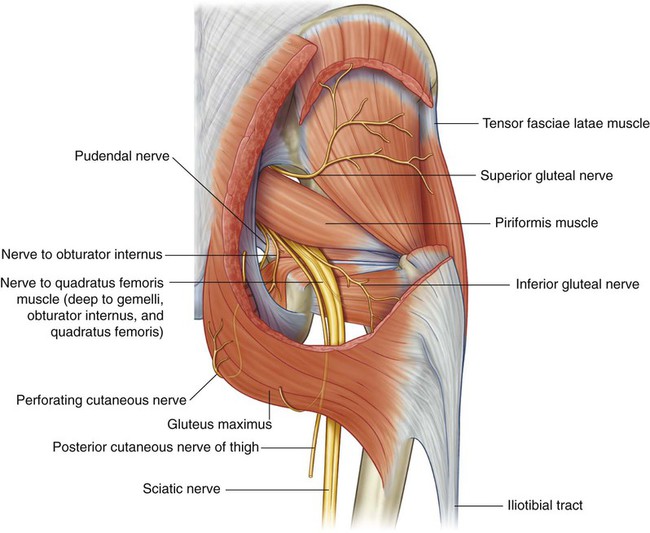

Nerves

Seven nerves enter the gluteal region from the pelvis through the greater sciatic foramen (Fig. 6.47): the superior gluteal nerve, sciatic nerve, nerve to the quadratus femoris, nerve to the obturator internus, posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh, pudendal nerve, and inferior gluteal nerve.

Superior gluteal nerve

Of all the nerves that pass through the greater sciatic foramen, the superior gluteal nerve is the only one that passes above the piriformis muscle (Fig. 6.47). After entering the gluteal region, the nerve loops up over the inferior margin of the gluteus minimus and travels anteriorly and laterally in the plane between the gluteus minimus and medius muscles.

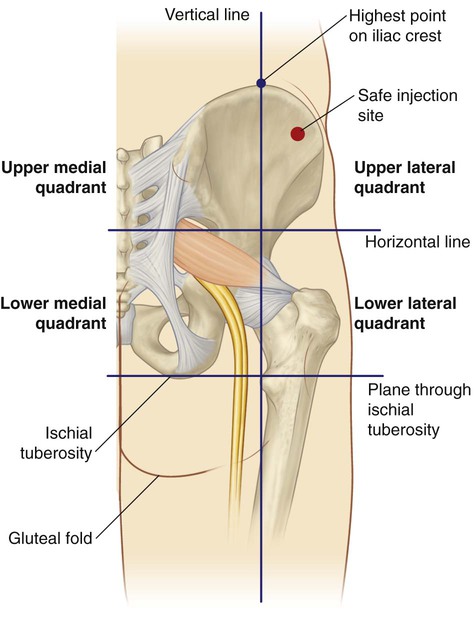

Sciatic nerve

The sciatic nerve enters the gluteal region through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle (Fig. 6.47). It descends in the plane between the superficial and deep group of gluteal region muscles, crossing the posterior surfaces of first the obturator internus and associated gemellus muscles and then the quadratus femoris muscle. It lies just deep to the gluteus maximus at the midpoint between the ischial tuberosity and the greater trochanter. At the lower margin of the quadratus femoris muscle, the sciatic nerve enters the posterior thigh.

Nerve to quadratus femoris

The nerve to the quadratus femoris enters the gluteal region through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle and deep to the sciatic nerve (Fig. 6.47). Unlike other nerves in the gluteal region, the nerve to the quadratus femoris lies anterior to the plane of the deep muscles.

Nerve to obturator internus

The nerve to the obturator internus enters the gluteal region through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle and between the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh and the pudendal nerve (Fig. 6.47). It supplies a small branch to the gemellus superior and then passes over the ischial spine and through the lesser sciatic foramen to innervate the obturator internus muscle from the medial surface of the muscle in the perineum.

Posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh

The posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh enters the gluteal region through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle and immediately medial to the sciatic nerve (Fig. 6.47). It descends through the gluteal region just deep to the gluteus maximus and enters the posterior thigh.

Pudendal nerve

The pudendal nerve enters the gluteal region through the greater sciatic foramen inferior to the piriformis muscle and medial to the sciatic nerve (Fig. 6.47). It passes over the sacrospinous ligament and immediately passes through the lesser sciatic foramen to enter the perineum. The course of the pudendal nerve in the gluteal region is short and the nerve is often hidden by the overlying upper margin of the sacrotuberous ligament.

Perforating cutaneous nerve

The perforating cutaneous nerve is the only nerve in the gluteal region that does not enter the area through the greater sciatic foramen. It is a small nerve that leaves the sacral plexus in the pelvic cavity by piercing the sacrotuberous ligament. It then loops around the lower border of the gluteus maximus to supply the skin over the medial aspect of the gluteus maximus (Fig. 6.47).

Arteries

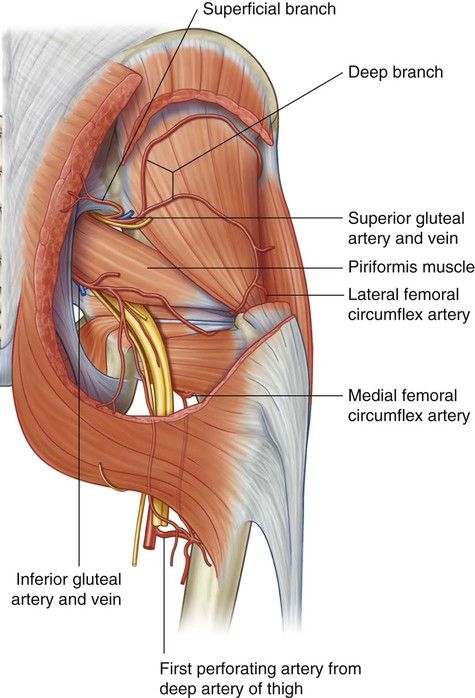

Two arteries enter the gluteal region from the pelvic cavity through the greater sciatic foramen, the inferior gluteal artery and the superior gluteal artery (Fig. 6.49). They supply structures in the gluteal region and posterior thigh and have important collateral anastomoses with branches of the femoral artery.

Superior gluteal artery

The superior gluteal artery originates from the posterior trunk of the internal iliac artery in the pelvic cavity. It leaves the pelvic cavity with the superior gluteal nerve through the greater sciatic foramen above the piriformis muscle (Fig. 6.49). In the gluteal region, it divides into a superficial branch and a deep branch:

The superficial branch passes onto the deep surface of the gluteus maximus muscle.

The superficial branch passes onto the deep surface of the gluteus maximus muscle.

The deep branch passes between the gluteus medius and minimus muscles.

The deep branch passes between the gluteus medius and minimus muscles.

In addition to adjacent muscles, the superior gluteal artery contributes to the supply of the hip joint. Branches of the artery also anastomose with the lateral and medial femoral circumflex arteries from the deep femoral artery in the thigh, and with the inferior gluteal artery (Fig. 6.50).

Thigh

The thigh is the region of the lower limb that is approximately between the hip and knee joints (Fig. 6.51):

Anteriorly, it is separated from the abdominal wall by the inguinal ligament.

Anteriorly, it is separated from the abdominal wall by the inguinal ligament.

Posteriorly, it is separated from the gluteal region by the gluteal fold superficially, and by the inferior margins of the gluteus maximus and quadratus femoris on deeper planes.

Posteriorly, it is separated from the gluteal region by the gluteal fold superficially, and by the inferior margins of the gluteus maximus and quadratus femoris on deeper planes.

Structures enter and leave the top of the thigh by three routes:

Posteriorly, the thigh is continuous with the gluteal region and the major structure passing between the two regions is the sciatic nerve.

Posteriorly, the thigh is continuous with the gluteal region and the major structure passing between the two regions is the sciatic nerve.

Anteriorly, the thigh communicates with the abdominal cavity through the aperture between the inguinal ligament and pelvic bone, and major structures passing through this aperture are the iliopsoas and pectineus muscles; the femoral nerve, artery, and vein; and lymphatic vessels.

Anteriorly, the thigh communicates with the abdominal cavity through the aperture between the inguinal ligament and pelvic bone, and major structures passing through this aperture are the iliopsoas and pectineus muscles; the femoral nerve, artery, and vein; and lymphatic vessels.

Medially, structures (including the obturator nerve and associated vessels) pass between the thigh and pelvic cavity through the obturator canal.

Medially, structures (including the obturator nerve and associated vessels) pass between the thigh and pelvic cavity through the obturator canal.

The thigh is divided into three compartments by intermuscular septa between the posterior aspect of the femur and the fascia lata (the thick layer of deep fascia that completely surrounds or invests the thigh; Fig. 6.51C):

The anterior compartment of the thigh contains muscles that mainly extend the leg at the knee joint.

The anterior compartment of the thigh contains muscles that mainly extend the leg at the knee joint.

The posterior compartment of the thigh contains muscles that mainly extend the thigh at the hip joint and flex the leg at the knee joint.

The posterior compartment of the thigh contains muscles that mainly extend the thigh at the hip joint and flex the leg at the knee joint.

The medial compartment of the thigh consists of muscles that mainly adduct the thigh at the hip joint.

The medial compartment of the thigh consists of muscles that mainly adduct the thigh at the hip joint.

Bones

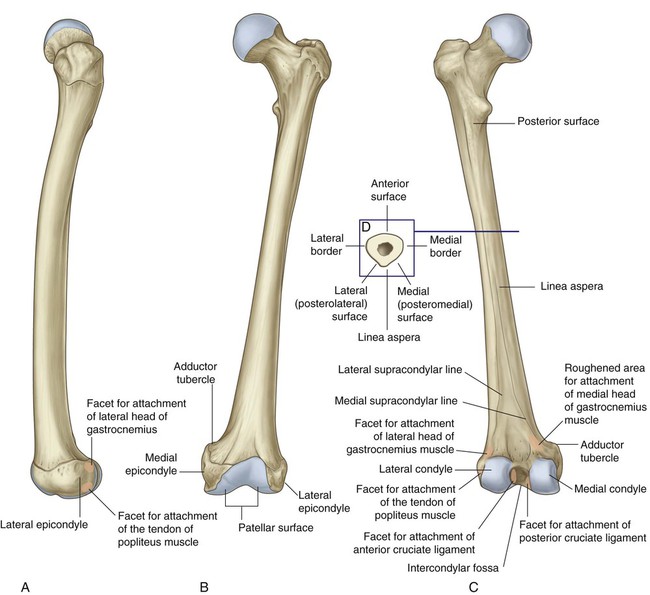

Shaft and distal end of femur

The shaft of the femur is bowed forward and has an oblique course from the neck of the femur to the distal end (Fig. 6.52). As a consequence of this oblique orientation, the knee is close to the midline under the body’s center of gravity.

The middle part of the shaft of the femur is triangular in cross section (Fig. 6.52D). In the middle part of the shaft, the femur has smooth medial (posteromedial), lateral (posterolateral), and anterior surfaces and medial, lateral, and posterior borders. The medial and lateral borders are rounded, whereas the posterior border forms a broad roughened crest—the linea aspera.

In proximal and distal regions of the femur, the linea aspera widens to form an additional posterior surface. At the distal end of the femur, this posterior surface forms the floor of the popliteal fossa, and its margins form the medial and lateral supracondylar lines. The medial supracondylar line terminates at a prominent tubercle (the adductor tubercle) on the superior aspect of the medial condyle of the distal end. Just lateral to the lower end of the medial supracondylar line is an elongate roughened area of bone for the proximal attachment of the medial head of the gastrocnemius muscle (Fig. 6.51).

The walls of the intercondylar fossa bear two facets for the superior attachment of the cruciate ligaments, which stabilize the knee joint (Fig. 6.52):

The wall formed by the lateral surface of the medial condyle has a large oval facet, which covers most of the inferior half of the wall, for attachment of the proximal end of the posterior cruciate ligament.

The wall formed by the lateral surface of the medial condyle has a large oval facet, which covers most of the inferior half of the wall, for attachment of the proximal end of the posterior cruciate ligament.

The wall formed by the medial surface of the lateral condyle has a posterosuperior smaller oval facet for attachment of the proximal end of the anterior cruciate ligament.

The wall formed by the medial surface of the lateral condyle has a posterosuperior smaller oval facet for attachment of the proximal end of the anterior cruciate ligament.

Epicondyles, for the attachment of collateral ligaments of the knee joint, are bony elevations on the nonarticular outer surfaces of the condyles (Fig. 6.52). Two facets separated by a groove are just posterior to the lateral epicondyle:

The upper facet is for attachment of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle.

The upper facet is for attachment of the lateral head of the gastrocnemius muscle.

The inferior facet is for attachment of the popliteus muscle.

The inferior facet is for attachment of the popliteus muscle.

The tendon of the popliteus muscle lies in the groove separating the two facets.

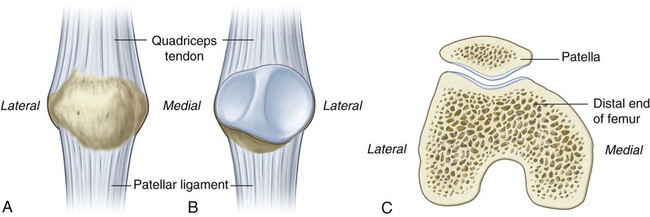

Patella

Its apex is pointed inferiorly for attachment to the patellar ligament, which connects the patella to the tibia (Fig. 6.53).

Its apex is pointed inferiorly for attachment to the patellar ligament, which connects the patella to the tibia (Fig. 6.53).

Its base is broad and thick for the attachment of the quadriceps femoris muscle from above.

Its base is broad and thick for the attachment of the quadriceps femoris muscle from above.

Its posterior surface articulates with the femur and has medial and lateral facets, which slope away from a raised smooth ridge—the lateral facet is larger than the medial facet for articulation with the larger corresponding surface on the lateral condyle of the femur.

Its posterior surface articulates with the femur and has medial and lateral facets, which slope away from a raised smooth ridge—the lateral facet is larger than the medial facet for articulation with the larger corresponding surface on the lateral condyle of the femur.

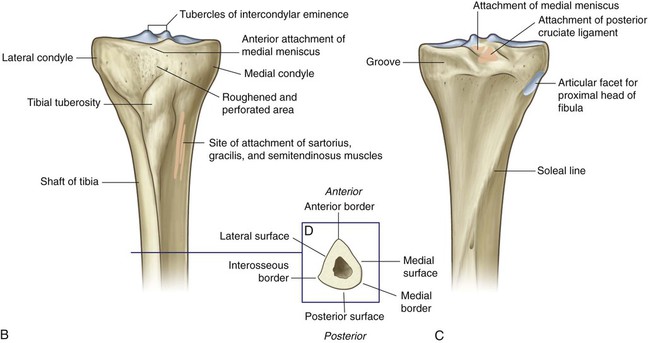

Proximal end of tibia

The proximal end of the tibia is expanded in the transverse plane for weight-bearing and consists of a medial condyle and a lateral condyle, which are both flattened in the horizontal plane and overhang the shaft (Fig. 6.54).

B. Anterior view. C. Posterior view. D. Cross section through the shaft of tibia.

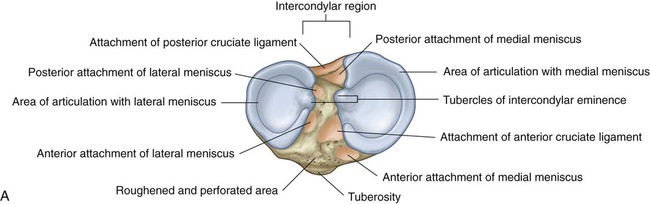

Tibial condyles and intercondylar areas

The tibial condyles are thick horizontal discs of bone attached to the top of the tibial shaft (Fig. 6.54).

The intercondylar region of the tibial plateau lies between the articular surfaces of the medial and lateral condyles (Fig. 6.54). It is narrow centrally where it is raised to form the intercondylar eminence, the sides of which are elevated further to form medial and lateral intercondylar tubercles.

The most anterior facet is for attachment of the anterior end (horn) of the medial meniscus.

The most anterior facet is for attachment of the anterior end (horn) of the medial meniscus.

Immediately posterior to the most anterior facet is a facet for the attachment of the anterior cruciate ligament.

Immediately posterior to the most anterior facet is a facet for the attachment of the anterior cruciate ligament.

A small facet for the attachment of the anterior end (horn) of the lateral meniscus is just lateral to the site of attachment of the anterior cruciate ligament.

A small facet for the attachment of the anterior end (horn) of the lateral meniscus is just lateral to the site of attachment of the anterior cruciate ligament.

The posterior intercondylar area also bears three attachment facets:

The most anterior is for attachment of the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus.

The most anterior is for attachment of the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus.

Posteromedial to the most anterior facet is the site of attachment for the posterior horn of the medial meniscus.

Posteromedial to the most anterior facet is the site of attachment for the posterior horn of the medial meniscus.

Behind the site of attachment for the posterior horn of the medial meniscus is a large facet for the attachment of the posterior cruciate ligament.

Behind the site of attachment for the posterior horn of the medial meniscus is a large facet for the attachment of the posterior cruciate ligament.

Tibial tuberosity

The tibial tuberosity is a palpable inverted triangular area on the anterior aspect of the tibia below the site of junction between the two condyles (Fig. 6.54). It is the site of attachment for the patellar ligament, which is a continuation of the quadriceps femoris tendon below the patella.

Shaft of tibia

The shaft of the tibia is triangular in cross section and has three surfaces (posterior, medial, and lateral) and three borders (anterior, interosseous, and medial) (Fig. 6.54D):

The anterior border is sharp and descends from the tibial tuberosity where it is continuous superiorly with a ridge that passes along the lateral margin of the tuberosity and onto the lateral condyle.

The anterior border is sharp and descends from the tibial tuberosity where it is continuous superiorly with a ridge that passes along the lateral margin of the tuberosity and onto the lateral condyle.

The interosseous border is a subtle vertical ridge that descends along the lateral aspect of the tibia from the region of bone anterior and inferior to the articular facet for the head of the fibula.

The interosseous border is a subtle vertical ridge that descends along the lateral aspect of the tibia from the region of bone anterior and inferior to the articular facet for the head of the fibula.

The medial border is indistinct superiorly where it begins at the anterior end of the groove on the posterior surface of the medial tibial condyle, but is sharp in midshaft.

The medial border is indistinct superiorly where it begins at the anterior end of the groove on the posterior surface of the medial tibial condyle, but is sharp in midshaft.

The lateral surface, between the anterior and interosseous borders, is smooth and unremarkable.

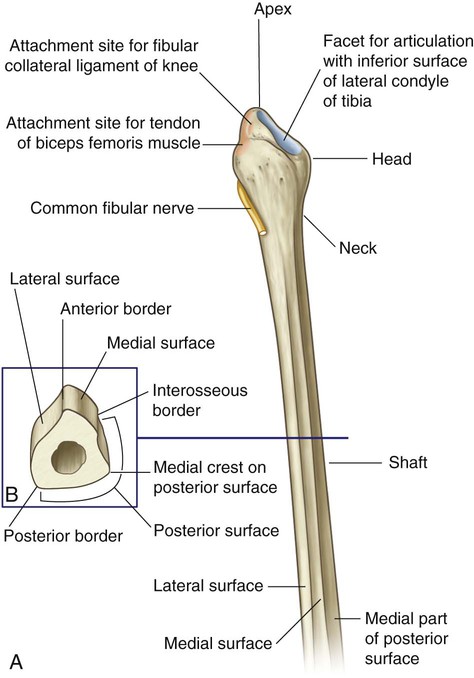

Proximal end of fibula

The head of the fibula is a globe-shaped expansion at the proximal end of the fibula (Fig. 6.55). A circular facet on the superomedial surface is for articulation above with a similar facet on the inferior aspect of the lateral condyle of the tibia. Just posterolateral to this facet, the bone projects superiorly as a blunt apex (styloid process).

Like the tibia, the shaft of the fibula has three borders (anterior, posterior, and interosseous) and three surfaces (lateral, posterior, and medial), which lie between the borders (Fig. 6.55):

Muscles

Muscles of the thigh are arranged in three compartments separated by intermuscular septa (Fig. 6.56).

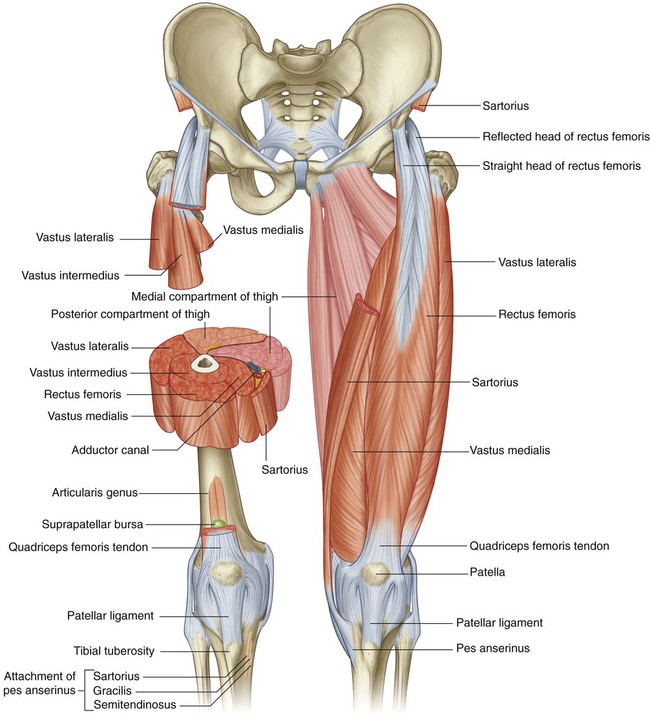

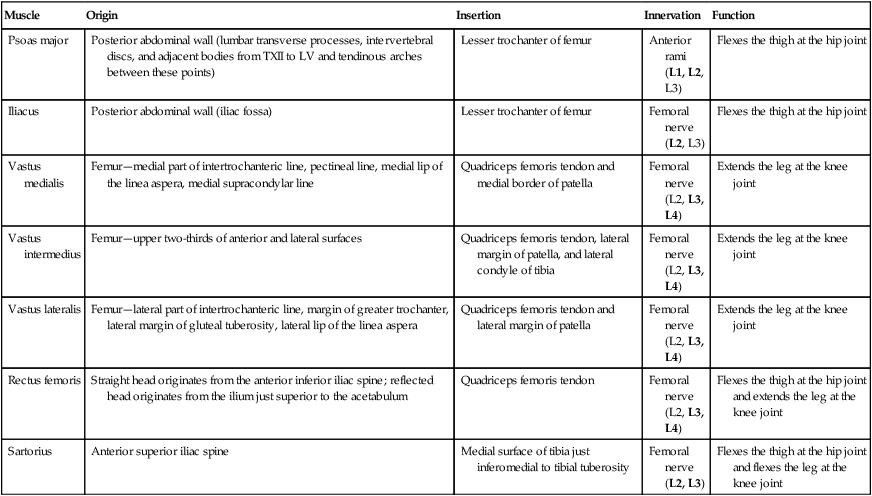

Anterior compartment

Muscles in the anterior compartment (Table 6.3) act on the hip and knee joints:

Table 6.3

Muscles of the anterior compartment of thigh (spinal segments in bold are the major segments innervating the muscle)

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Function |

| Psoas major | Posterior abdominal wall (lumbar transverse processes, intervertebral discs, and adjacent bodies from TXII to LV and tendinous arches between these points) | Lesser trochanter of femur | Anterior rami (L1, L2, L3) | Flexes the thigh at the hip joint |

| Iliacus | Posterior abdominal wall (iliac fossa) | Lesser trochanter of femur | Femoral nerve (L2, L3) | Flexes the thigh at the hip joint |

| Vastus medialis | Femur—medial part of intertrochanteric line, pectineal line, medial lip of the linea aspera, medial supracondylar line | Quadriceps femoris tendon and medial border of patella | Femoral nerve (L2, L3, L4) | Extends the leg at the knee joint |

| Vastus intermedius | Femur—upper two-thirds of anterior and lateral surfaces | Quadriceps femoris tendon, lateral margin of patella, and lateral condyle of tibia | Femoral nerve (L2, L3, L4) | Extends the leg at the knee joint |

| Vastus lateralis | Femur—lateral part of intertrochanteric line, margin of greater trochanter, lateral margin of gluteal tuberosity, lateral lip of the linea aspera | Quadriceps femoris tendon and lateral margin of patella | Femoral nerve (L2, L3, L4) | Extends the leg at the knee joint |

| Rectus femoris | Straight head originates from the anterior inferior iliac spine; reflected head originates from the ilium just superior to the acetabulum | Quadriceps femoris tendon | Femoral nerve (L2, L3, L4) | Flexes the thigh at the hip joint and extends the leg at the knee joint |

| Sartorius | Anterior superior iliac spine | Medial surface of tibia just inferomedial to tibial tuberosity | Femoral nerve (L2, L3) | Flexes the thigh at the hip joint and flexes the leg at the knee joint |

the psoas major and iliacus act on the hip joint,

the psoas major and iliacus act on the hip joint,

the sartorius and rectus femoris act on both the hip and knee joints, and

the sartorius and rectus femoris act on both the hip and knee joints, and

Quadriceps femoris—vastus medialis, intermedius, and lateralis and rectus femoris

The large quadriceps femoris muscle consists of three vastus muscles (vastus medialis, vastus intermedius, and vastus lateralis) and the rectus femoris muscle (Fig. 6.58).

The vastus medialis originates from a continuous line of attachment on the femur, which begins anteromedially on the intertrochanteric line and continues posteroinferiorly along the pectineal line and then descends along the medial lip of the linea aspera and onto the medial supracondylar line. The fibers converge onto the medial aspect of the quadriceps femoris tendon and the medial border of the patella (Fig. 6.58).

The vastus intermedius originates mainly from the upper two-thirds of the anterior and lateral surfaces of the femur and the adjacent intermuscular septum (Fig. 6.58). It merges into the deep aspect of the quadriceps femoris tendon and also attaches to the lateral margin of the patella and lateral condyle of the tibia.

A tiny muscle (articularis genus) originates from the femur just inferior to the origin of the vastus intermedius and inserts into the suprapatellar bursa associated with the knee joint (Fig. 6.58). This articular muscle, which is often part of the vastus intermedius muscle, pulls the bursa away from the knee joint during extension.

The vastus lateralis is the largest of the vastus muscles (Fig. 6.58). It originates from a continuous line of attachment, which begins anterolaterally from the superior part of the intertrochanteric line of the femur and then circles laterally around the bone to attach to the lateral margin of the gluteal tuberosity and continues down the upper part of the lateral lip of the linea aspera. Muscle fibers converge mainly onto the quadriceps femoris tendon and the lateral margin of the patella.

Unlike the vastus muscles, which cross only the knee joint, the rectus femoris muscle crosses both the hip and the knee joints (Fig. 6.58).

The rectus femoris has two tendinous heads of origin from the pelvic bone:

The patellar ligament is functionally the continuation of the quadriceps femoris tendon below the patella and is attached above to the apex and margins of the patella and below to the tibial tuberosity (Fig. 6.58). The more superficial fibers of the quadriceps femoris tendon and the patellar ligament are continuous over the anterior surface of the patella, and lateral and medial fibers are continuous with the ligament beside the margins of the patella.

Sartorius

The sartorius muscle is the most superficial muscle in the anterior compartment of the thigh and is a long strap-like muscle that descends obliquely through the thigh from the anterior superior iliac spine to the medial surface of the proximal shaft of the tibia (Fig. 6.58). Its flat aponeurotic insertion into the tibia is immediately anterior to the insertion of the gracilis and semitendinosus muscles.

In the middle one-third of the thigh, the sartorius forms the anterior wall of the adductor canal.

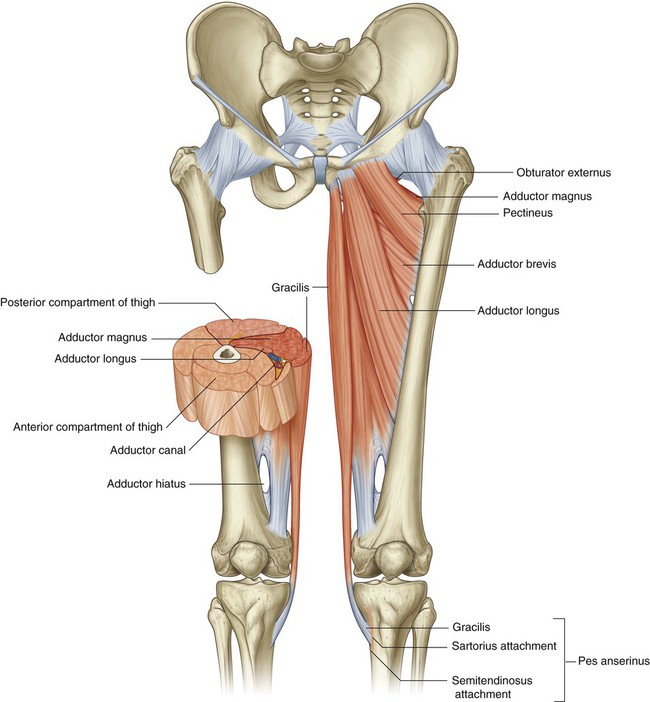

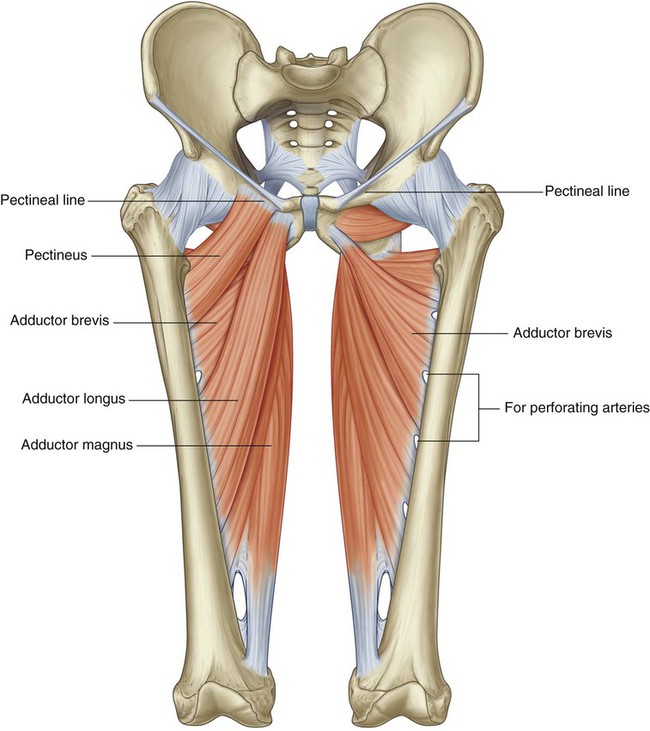

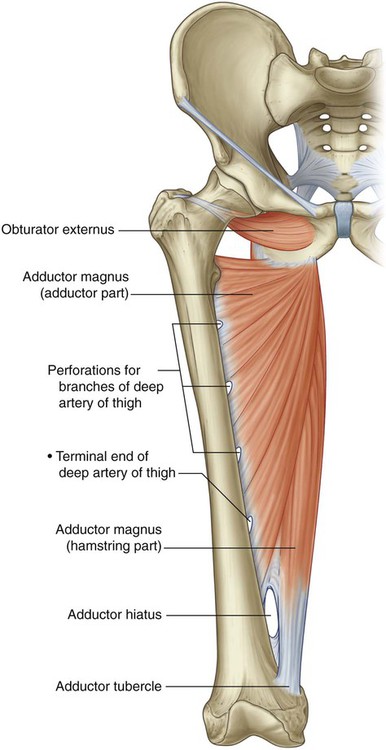

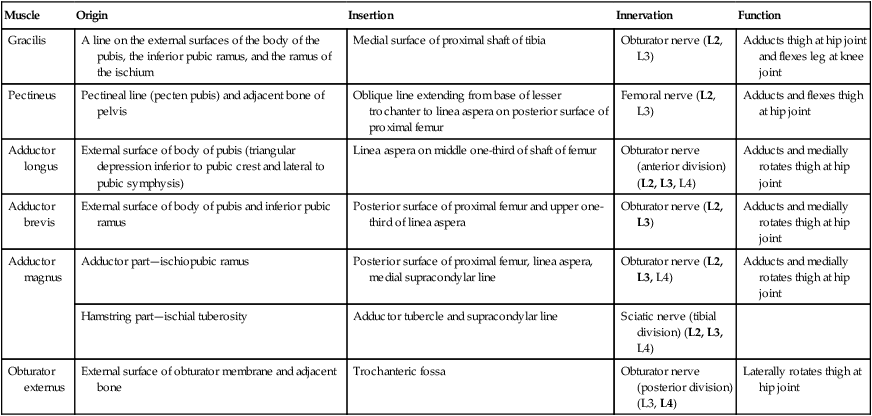

Medial compartment

There are six muscles in the medial compartment of the thigh (Table 6.4): gracilis, pectineus, adductor longus, adductor brevis, adductor magnus, and obturator externus (Fig. 6.59). Collectively, all these muscles except the obturator externus mainly adduct the thigh at the hip joint; the adductor muscles may also medially rotate the thigh. Obturator externus is a lateral rotator of the thigh at the hip joint.

Table 6.4

Muscles of the medial compartment of thigh (spinal segments in bold are the major segments innervating the muscle)

| Muscle | Origin | Insertion | Innervation | Function |

| Gracilis | A line on the external surfaces of the body of the pubis, the inferior pubic ramus, and the ramus of the ischium | Medial surface of proximal shaft of tibia | Obturator nerve (L2, L3) | Adducts thigh at hip joint and flexes leg at knee joint |

| Pectineus | Pectineal line (pecten pubis) and adjacent bone of pelvis | Oblique line extending from base of lesser trochanter to linea aspera on posterior surface of proximal femur | Femoral nerve (L2, L3) | Adducts and flexes thigh at hip joint |

| Adductor longus | External surface of body of pubis (triangular depression inferior to pubic crest and lateral to pubic symphysis) | Linea aspera on middle one-third of shaft of femur | Obturator nerve (anterior division) (L2, L3, L4) | Adducts and medially rotates thigh at hip joint |

| Adductor brevis | External surface of body of pubis and inferior pubic ramus | Posterior surface of proximal femur and upper one-third of linea aspera | Obturator nerve (L2, L3) | Adducts and medially rotates thigh at hip joint |

| Adductor magnus | Adductor part—ischiopubic ramus | Posterior surface of proximal femur, linea aspera, medial supracondylar line | Obturator nerve (L2, L3, L4) | Adducts and medially rotates thigh at hip joint |

| Hamstring part—ischial tuberosity | Adductor tubercle and supracondylar line | Sciatic nerve (tibial division) (L2, L3, L4) | ||

| Obturator externus | External surface of obturator membrane and adjacent bone | Trochanteric fossa | Obturator nerve (posterior division) (L3, L4) | Laterally rotates thigh at hip joint |

Gracilis

The gracilis is the most superficial of the muscles in the medial compartment of thigh and descends almost vertically down the medial side of the thigh (Fig. 6.59). It is attached above to the outer surface of the ischiopubic ramus of the pelvic bone and below to the medial surface of the proximal shaft of the tibia, where it lies sandwiched between the tendon of sartorius in front and the tendon of the semitendinosus behind.

Pectineus

The pectineus is a flat quadrangular muscle (Fig. 6.60). It is attached above to the pectineal line of the pelvic bone and adjacent bone, and descends laterally to attach to an oblique line extending from the base of the lesser trochanter to the linea aspera on the posterior surface of the proximal femur.

The pectineus adducts and flexes the thigh at the hip joint and is innervated by the femoral nerve.

Adductor longus