CHAPTER 15 Lower Blepharoplasty: Blending the Lid/Cheek Junction with Orbicularis Muscle and Lateral Retinacular Suspension

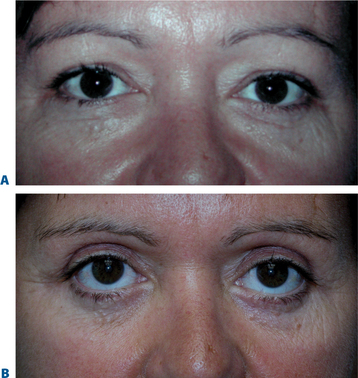

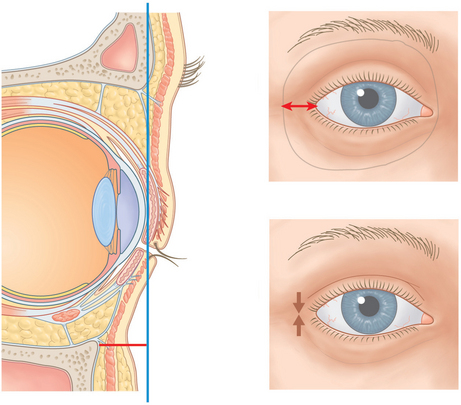

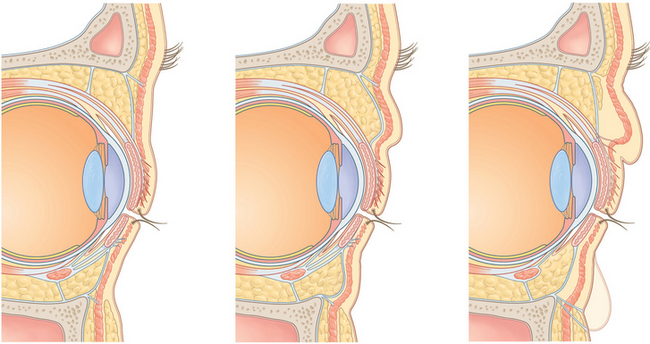

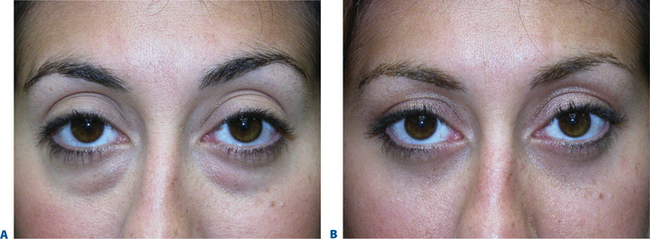

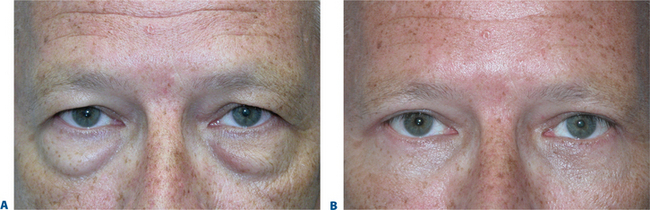

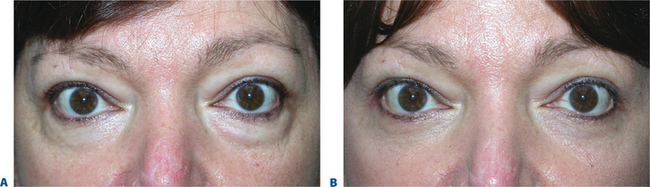

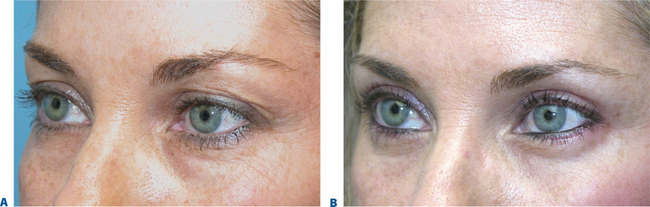

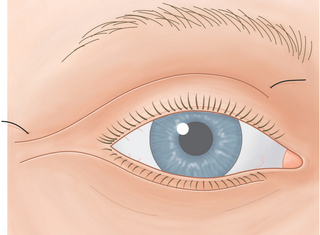

Similar to many facial aesthetic procedures, the current methods used in lower blepharoplasty have evolved for many reasons, including the lack of satisfaction with previous methods, complications arising from traditional surgical approaches, a better understanding of the anatomy of the aging periorbita and appreciation of the components of youth. Traditional lower blepharoplasty, for instance, performed 20 years ago typically incorporated a lower eyelid, infraciliary skin/muscle flap and excision of orbital fat through this incision by violating the orbital septum and performed without routine canthal reinforcement. The surgical efforts were basically a perceived solution to the antiquated notion of getting rid of ‘excess’ soft tissue (skin, muscle, and fat) in addition to straightforward access to lower eyelid fat without regard for the concurrent senescence of supporting structures. Depending on the patient’s presentation as well as the aggressiveness of the surgical procedures, a varying degree of lower eyelid malposition was met, and fortunately dissatisfaction of the overall appearance of the lower periorbita was uncommon. Patients could usually detect an overall improvement (‘bags were gone’) of their appearance and often accepted a varying degree of lid malposition, hollowness, and scarring as routine (Fig. 15-1). These results were often published with great pride, as the perception of the improvement in the few noted areas and the lack of options available fostered the acceptance of these results. Even the most noted surgeons were achieving these results and many were complacent that this was ‘the best that could be done.’

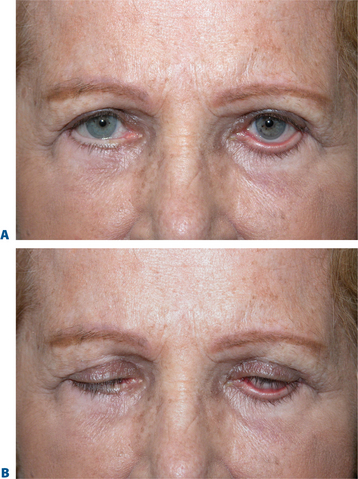

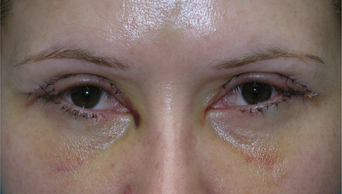

The emergence of a greater appreciation of the ‘oculoplastic surgeon’ to a large degree emanated from referrals by these noted surgeons whose patients experienced eyelid changes that were outside the acceptable range (lid retraction, ectropion, lagophthalmos, onset or exacerbation of long-term dry eye symptoms, etc.) (Fig. 15-2). Based primarily on the ophthalmologist’s exposure to periorbital anatomy and lower eyelid reconstruction, repair of lid malposition and the like were accomplished via procedures to horizontally tighten or shorten the lower eyelid to better position the eyelid/globe interface and effectively aid lower eyelid posture. The improvement of sometimes disastrous situations was appreciated despite the reality that the lid changes could rarely be fully restored (Fig. 15-3). Surgeons who treated these problems usually incorporated techniques such as the lateral tarsal strip1 or other methods that shortened the lower eyelid horizontally2 in an attempt to reduce vertical lower eyelid distraction by increasing horizontal lid tension. The improvement was notable and became the accepted standard of care. These procedures, in most cases however, might have been avoided if a lower eyelid/canthal reinforcement was performed at the time of the initial surgery. Why, however, were these latter procedures not routinely performed?

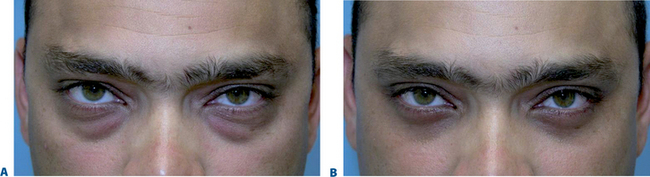

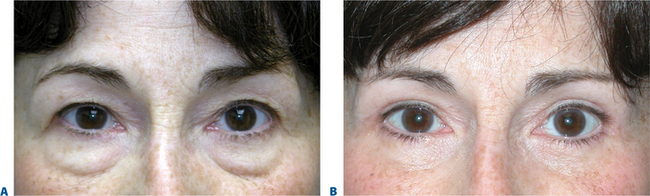

One possible explanation for the avoidance of routine canthal support is that the anatomy of the lateral canthus and traditional canthal reinforcement procedures are both complex to understand and the reconstruction of the lower eyelid and lateral canthus commonly heralded complications including asymmetry, canthal misalignment and eventual shortening of the horizontal palpebral aperture after fixation was lost. Instead of incorporating methods that were proactive in supporting the lower eyelid, many surgeons either avoided lower blepharoplasty, accepted varying mild to moderate degrees of eyelid malposition, or adopted other procedures that were suboptimal in restoring the youthful complement. The transconjunctival approach to removal of lower eyelid fat then became popular due to the negligible change in lid position,3 while at the same time improving lower eyelid ‘bags’ (Fig. 15-4). Except for the rare very young individual with good soft tissue tone and elasticity, the improvement of the lower eyelid ‘bulges,’ however, were often met with worsening of the appearance of the lower eyelid skin surface, either relating to a deflationary effect and diversion of attention from bags to lower eyelid skin/soft tissue quality. It is my opinion that for all the wrong reasons, laser skin resurfacing of this region then became more popular, combined with transconjunctival removal of fat, in order to improve the appearance of the skin.4 This anatomic and surgical oversimplification (volume depleting the lower eyelid by fat removal combined with exfoliating the skin) can produce significant improvement to the appearance of the lower periorbita.5 I too employed this procedure earlier in my practice and realized that with significant degrees of application of laser energy to improve lower eyelid skin appearance, eyelid retraction was at the very least temporary, and canthal support (via a simple suture canthopexy without surgical release) could maintain or improve the lower eyelid posture. While I was not convinced that horizontal shortening type procedures like the lateral tarsal strip were prudent in such situations, I explored the ability to effectively suspend the lateral canthus via suture, hopefully in a way that was better than prior attempts at suture canthopexy6 (Fig. 15-5).

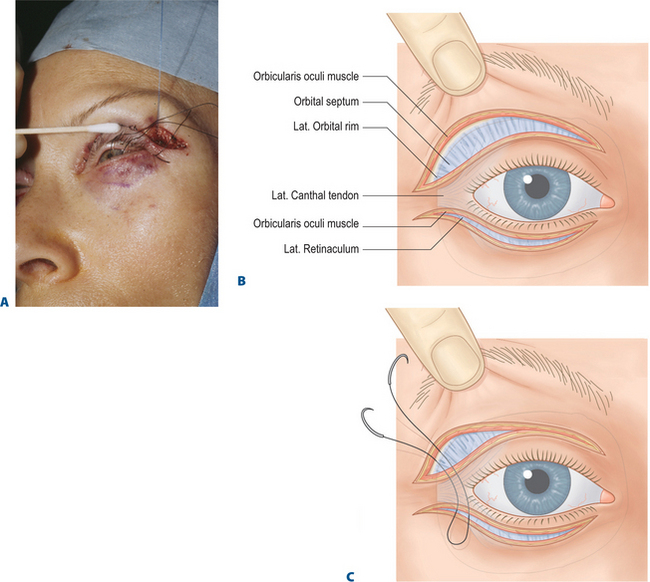

This was obviously not the first suture canthopexy procedure developed. One glimpse at the 1993 issue of Clinics in Plastic Surgery edited by Dr Robert Flowers7 reveals the current thinking on a spectrum of canthal support procedures. Most suture suspension procedures were considered unsatisfactory, with the exception of those that required minimal support (usually in the younger patient) as it was felt that loss of fixation (long-term) was inevitable. Techniques evolved and were modified8 that included the incorporation of drill holes through the lateral orbital rim for individuals where either periosteum in this region was deemed inadequate,7 or where it was presumed that failed canthopexy often related to a point of disinsertion. On the other hand, I felt that good periosteal purchases (fixation) were likely to be more long lasting than the entrance of the suture (below) through the lateral canthal ligament.6,9 The lateral retinacular suspension was essentially another variety of suture canthopexy, whereby the canthal system was reinforced by a suture suspension that was delivered through a lower eyelid incision with the opportunity of using variable vectors of support by exiting the suture through the upper eyelid at a multitude of levels (Fig. 15-6). It seemed clearer to me later that with ongoing orbicularis muscular function at the lateral canthus with subconscious and frequent animation, that the likely point of eventual disinsertion would be here at the lateral commissure rather than at the periosteum at the orbital rim. While I recognized the need for some sort of canthal support in patients undergoing CO2 laser skin resurfacing to the lower eyelid and canthus, I was then unsure of how long the supportive effects could be expected. I began incorporating a lateral retinacular suspension procedure routinely with my laser skin resurfacing procedures to the lower eyelid through a 2–3 mm incision at the lateral commissure (Fig. 15-7). I found that reinforcing the polypropylene suture with Vicryl sutures (see p. 171) at the commissure either reduced or slowed down the disinsertion at the lateral canthal tendon and often many months (even years) later found that the suture was still attached to the lateral orbital rim. As this maneuver aided my many patients who had undergone laser skin resurfacing, I then began to extend the lateral retinacular suspension procedure to skin flap lower eyelid surgery which has been the mainstay of my lower blepharoplasty to date.

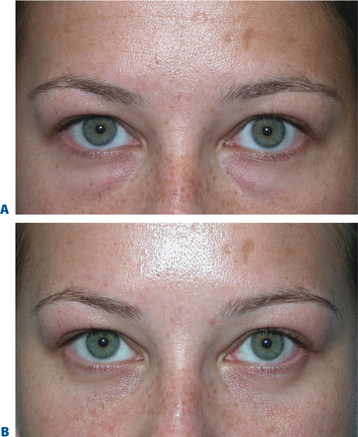

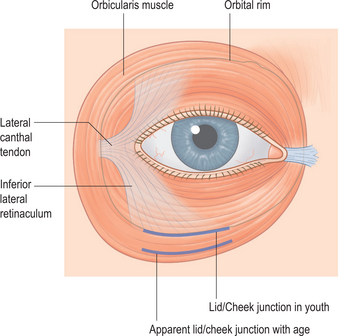

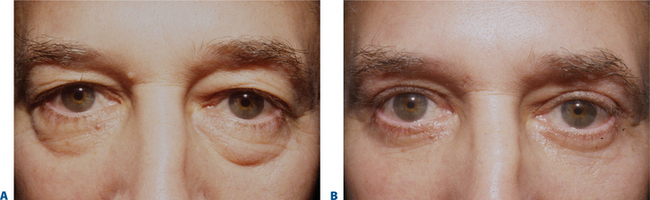

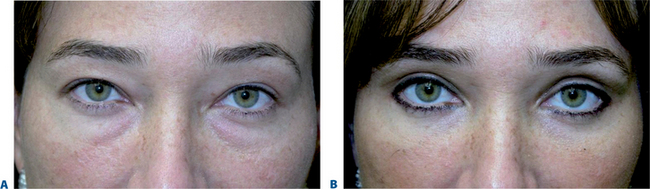

It has also been my opinion that despite the fact that skin quality appearance could be improved by laser skin resurfacing, the aging pathology of the lower periorbita as well illustrated by Drs Harris and Mendelson in their facial anatomy chapter in this book (see Chapter 5) and other writings10,11 indicates that it rests greatly on the orbicularis muscle and its retaining ligaments (Figs 15-8, 15-9). I believe this is due to a complicated combination of life-long animation, descent and hypotonia of the orbicularis, and atrophy of the adjacent periorbital soft tissue (skin, subcutaneous fat, ligamentous attachments) that allows the lower orbital fat to be anteriorly displaced combined with radial expansion of the soft tissues which better explains the lower periorbital ‘bulges’ (Fig. 15-10). As I believe that laser skin resurfacing was an abbreviated remedy, I also realized that skin–muscle flap surgery was often ineffective in significantly improving the lower eyelid skin. In lieu of this, I began re-exploring the use of skin flap dissection in an attempt to create an advancement flap of skin only (that contracts as do all advancement flaps) which would hopefully improve the lower eyelid skin rhytids and overall appearance. This plane of dissection also interrupts the attachments of orbicularis to the deep dermis which is a component of the cause of lower eyelid rhytids. Combined with adequate stabilization of the lower eyelid and lateral canthus via effective canthopexy and orbicularis muscle suspension, the skin tightening improved its appearance without inducing lid malposition. After many procedures utilizing this technique, it became clearer to me that this approach could improve lower eyelid skin appearance, at times to the same degree as laser skin resurfacing. The advantage of this approach also allowed me to expose the orbital component of the orbicularis oculi muscle throughout the lower eyelid and at the lateral canthus for further rejuvenative refinement.

Another reason to expose the orbicularis oculi muscle (via a carefully executed skin flap dissection) is for the ability to precisely address the hypotonic and less-supported orbicularis muscle. The ability to accurately and individually manipulate orbicularis muscle after a skin–muscle flap dissection, on the other hand, is dramatically diminished by definition, with this commonly used approach. Thereby, the use of a skin–muscle flap without independent orbicularis suspension reduces the transmission of tension across most of the lower periorbita to accomplish the desired effects. The extent of the dissection of the skin flap in this procedure will depend on both how much skin quality improvement (vertical dissection and eventual excision) is optimal and how much orbicularis muscle will be mobilized independent of the skin flap. A secondary effect of incision through the orbicularis composite at the lateral commissure is to release the superficial head of the lateral canthal tendon from components of the inferior retinaculum. In addition, the ability to use the orbicularis muscle to reinforce the lower eyelid provides for a better environment (along with canthopexy) for the safe excision of lower eyelid skin. Through this lateral orbicularis muscle dissection the surgeon also has the ability to enter what has been called the ‘lateral tarsal strap’12 which is a confluence of lateral retinacular soft tissue that attaches to the lateral inferior orbital rim. Those that had been well versed in canthal surgery realized that even when performing a lateral tarsal strip canthoplasty, full release of the lateral canthal tendon and lateral tarsus is only achieved by incising beneath the lower eyelid retractors at the lateral inferior orbital rim. This allows repositioning of the commissure in a way that a simple suture canthopexy can not. Typical canthopexy sutures placed without lysis of the orbital attachments likely regress fully to the original position, and at times are even inferiorly and dystopically mal-positioned due to the false sense of security of the initial canthopexy procedure that encourages removal of skin (and at times muscle) from this region. Full or partial release of the lateral canthal tendon from the inferior retinaculum including orbicularis and the ‘lateral strap’ allows for a more complete mobilization of the lateral canthal tendon through the ability to manipulate the superficial head of the lateral canthal tendon. I find this maneuver essential in not only the ability to manipulate orbicularis muscle for tightening and for dissection (if necessary) of the orbicularis retaining ligaments to the orbital rim, but again for release of the inferior retinacular component of the lateral commissure to facilitate long-term effective canthal suspension. A full release of the deep head to the lateral canthal tendon can also (rarely necessary, especially in primary lower blepharoplasty) be performed if an even higher position of the lateral commissure is required. Lateral retinacular suspension then becomes more effective as a permanent canthoplasty procedure, as with advanced healing as the suture suspension effect is lost, yet the elevated position of the commissure ‘scars’ into this position quite securely. Once the lateral retinacular suspension is performed orbicularis manipulation is then carried out through this incision. Skin re-draping and excision is then performed and each component proceeds with as much fortitude as required with the prior step reinforcing the lower eyelid in a way that facilitates the lower eyelid soft tissue manipulation and excision.

Transconjunctival fat maintenance, lower eyelid skin flap with orbicularis oculi and lateral retinacular suspension

Steps

1. Injection of local anesthesia

If upper blepharoplasty is performed, as mentioned in the upper blepharoplasty chapter (see Chapter 8), the lateral 1/4 of the upper eyelid remains open prior to the lower blepharoplasty. In this situation, the lower eyelid has already been injected with the preferred anesthetic mixture (I use a 50 : 50 combination of 2% lidocaine with epinephrine 1/200,000 dilution and 0.75 bupivicaine) using a fine, short (½ inch; 27–30 g) needle and under loop magnification the infratarsal, subconjunctival space has been infiltrated. Usually 1–2 ml of the anesthetic agent is all that is required if adequate IV sedation is concurrently administered. Skin infiltration with anesthetic is performed later, after satisfactory transconjunctival fat contouring.

2. Transconjunctival approach to lower eyelid fat maintenance

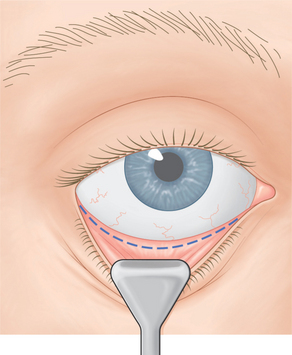

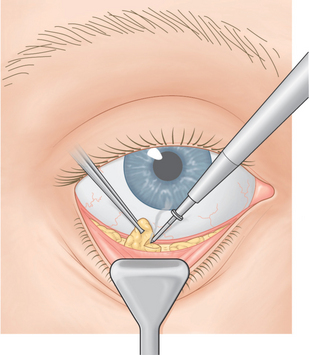

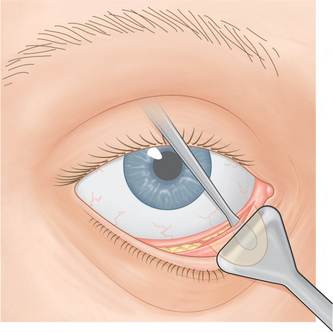

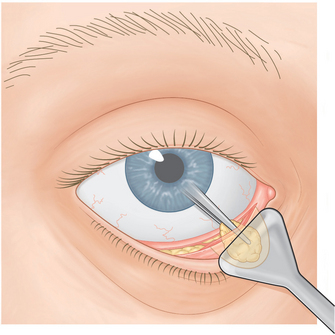

A medium-sized DesMarres eyelid retractor is used to inferiorly displace the lower eyelid by the assistant and the inferior fornix and inferior tarsal region is exposed (Fig. 15-11). There always seems to be a question of the exact and ideal location of the incision for this approach. Simply stated, the incision should be placed where the fat is most easily accessible. In some patients this is mid-way between the inferior tarsal border and the inferior fornix and sometimes when fat is more posteriorly located (as in the lateral fat pad) the incision is contoured deeper into the inferior cul-de-sac and more distant from the inferior tarsus. With counter (posterior) ballotment of the globe using an acrylic eyelid plate over the protective corneal/scleral contact lens, the fat ‘bulge’ is quite readily seen in most patients. A fine-tip needle Bovie cautery is then used to incise through conjunctiva and the lower eyelid retractors in pure cutting mode. This reduces the ‘char’ and allows for a precise incision and minimizes lateral thermal coagulation of the soft tissues. Although there is a mild degree of coagulation which is afforded via this method, however, any significant bleeding should be addressed with the coagulation mode. I begin by exposing the fat pads through this incision, however addressing contouring of the lateral (most posterior and superiorly placed position pad) first (Fig. 15-12). This is often the pad that is left untreated (or under-treated) as when the more medial fat pads are addressed the lateral pad may be more difficult to expose. Conservative amounts of fat may be excised, however when minimal fat is noted, diathermy only may be used to approach ‘shrinkage’ of the lower periorbital fat pads. The lower eyelid skin has not yet been injected until this point, and the evaluation of the anterior surface contours for the determination of optimal fat maintenance is more easily detected. In the scenario of a significant ‘tear trough deformity’ a small pocket is dissected through the transconjunctival incision medially and orbicularis muscle at the medial orbital rim is reflected from periosteum (Fig. 15-13). This maneuver in itself may be sufficient to diminish a mild depression, however if the contour defect is significant, a free fat graft that is obtained from a region where fat was excised in either the upper or lower eyelid is positioned into the ‘pocket’ (Fig. 15-14). Contouring is performed to the extent that the lower periorbital bulges are satisfactorily transposed, excised or shrunk to the point of optimal ‘concavity’ when the globe is balloted posteriorly with the surgeon’s fingers. At times even with diathermy alone there appears to be a significant excavation of the anterior surface, however as the patient is typically supine this will give a false impression of ‘overcorrection.’ Again, this can easily be discerned by depressing the globe posteriorly and watching the contours, and the surgeon should proceed slowly and precisely while continuously observing the anterior lower eyelid (skin) surface until the contours are satisfactory with this maneuver.

3. Lower eyelid skin incision and skin flap dissection

After this is achieved, the anterior skin surface is injected with the anesthetic solution subdermally and avoidance of injection into the orbicularis muscle is attempted. While the identical procedure (transconjunctival) is performed on the contralateral side, vasoconstriction and anesthetic effect to the skin and muscle is then achieved. Once transconjunctival fat maintenance procedures are performed on the contralateral side, attention is redirected to the first side. A skin incision is then made just beneath the eyelashes using a #15 Bard-Parker blade and extends in the same line (latitude) through the lateral canthus rather than a downward distraction of the incision which is typically and erroneously (in my opinion) performed (Fig. 15-15). A 4-0 silk traction suture is then placed through a more central aspect of the lower eyelid through tarsus for upward traction and the assistant then places cotton tip application or digital traction to the lower eyelid skin flap. Meticulous dissection is then performed (I prefer a battery-powered disposable cautery) to create an adequate skin flap depending on the pathology presented (Fig. 15-16). If there is significant redundant skin, especially when combined with dense rhytid, a widely undermined skin flap may be performed. Care must be taken to avoid ‘button-holing’ through the skin surface which can be avoided by careful application by both you and your assistant. Dissection is carried laterally beyond the commissure to expose the superior-lateral retinaculum and orbicularis muscle in this region. Subcutaneous veins can be treated with diathermy through the skin dissection.

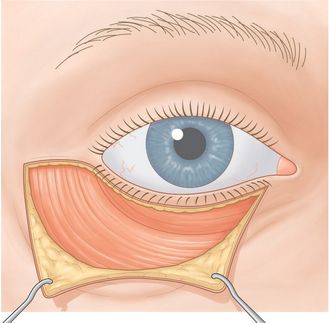

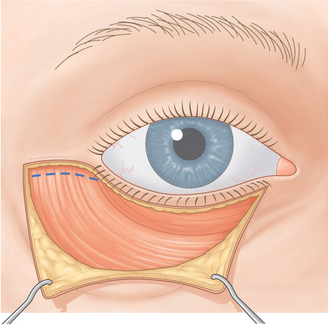

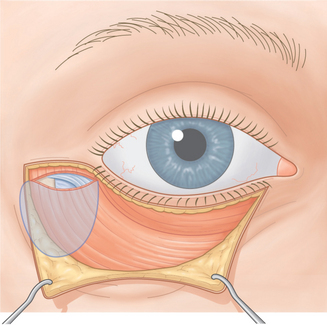

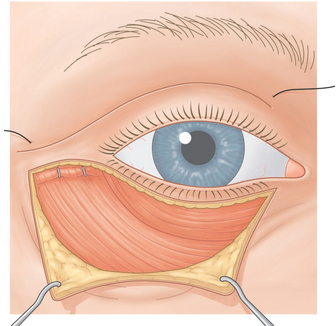

4. Orbicularis muscle incision and dissection

Once the skin dissection is performed the same hand held cautery unit is used to incise through orbicularis muscle 2–3 mm below the lateral commissure (Fig. 15-17) beginning at about the level of the commissure laterally to the lateral extent of the skin incision or as wide as necessary to mobilize orbicularis muscle appropriate for each patient (Fig. 15-18). Dissection is performed to the lateral orbital rim and for as much release as required for both mobilization of orbicularis muscle, release of the inferior retinaculum from the lateral canthal tendon, and release of the inferior ‘tarsal strap’ depending on how much super placement is required (Fig. 15-19). It is uncommon to require dissection along the more medial aspects of the inferior orbital rim to disinsert or completely release the orbicularis retaining ligaments.

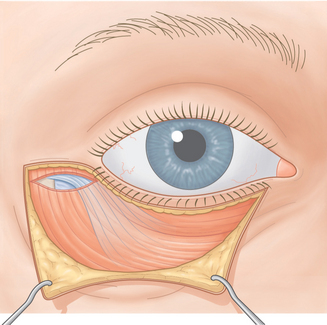

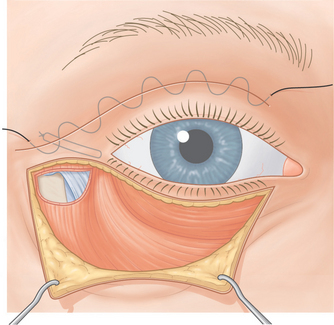

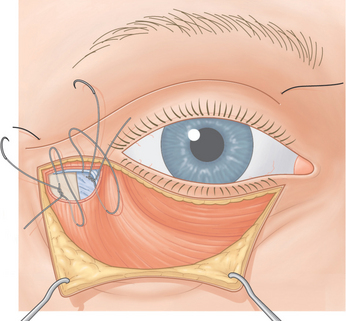

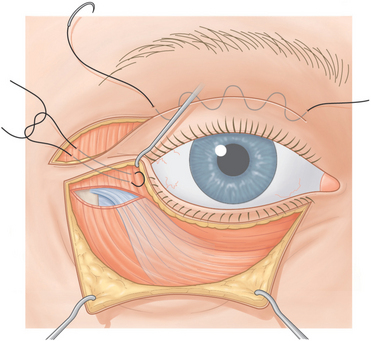

5. Lateral retinacular (canthal) suspension

A double arm 4-0 or 5-0 polypropylene suture is then placed through the lateral canthal ligament. I prefer the use of a polypropylene suture on a cardiovascular taper needle (US Surgical, Norwalk, CT) as this causes minimal to no shearing of the periosteum and the taper point puncture to periosteum is more likely to remain secure. Each arm of the suture is brought through periosteum (in most instances) at the level of the lateral tubercle but will vary depending on the patient’s orbital morphology and the position of the commissure desired (see Chapter 4). As the upper blepharoplasty procedure has maintained all orbicularis muscle (see Chapter 8) this maneuver is performed mostly by palpation whereby the dominant hand advancing the surgical needle and needle holder is used to place the suture through the lateral canthal tendon, through to the inner aspect of the lateral orbital rim through periosteum (Fig. 15-20). The non-dominant hand grasping a toothed forceps is used to palpate the exit of the suture through periosteum and direct this through the orbicularis muscle at the lateral upper eyelid. Sutures are usually placed 2–3 mm apart for the canthal suspension. Once satisfactory placement is made, the suture is tied beneath the cuff of orbicularis at the lateral upper eyelid wound (Fig. 15-21). Varying degrees of reinforcement with a loop of polypropylene at the lateral canthus (prior to tying) can be achieved by a 6-0 Vicryl ‘lasso’ suture around each arm of the penetration of the polypropylene suture at the lateral canthal tendon. This increases the drag coefficient whereby a typical monofilament suture would simply ‘cheese-wire’ through the tissue. By securing each arm of the suture to the lateral canthal tendon with the ‘lasso’ suture the polypropylene canthal suspension suture remains secure for a much longer period of time that translates to a more secure canthopexy. One should be certain that the suture knot is adequately positioned beneath a cuff of the orbicularis muscle (to reduce visibility and palpability of the suture long-term) and that there is a secure ‘purchase’ at the lateral orbital rim periosteum as superficial placement will yield both a significantly more brief suspension effort which could be problematic with significant muscle and skin mani-pulation and postoperative edema and/or misalignment of the lower eyelid and globe interface. After securing the polypropylene suture the upper eyelid wound closure is completed using the interrupted or continuous 6-0 nylon sutures.

Figure 15-20 After the necessary release is achieved, the lateral commissure can be repositioned that is now independent of the inferior attachments. The vector and direction of suture suspension/placement will vary (see Fig. 15-6) and is dependent on both the orbital morphology and the desired effect.

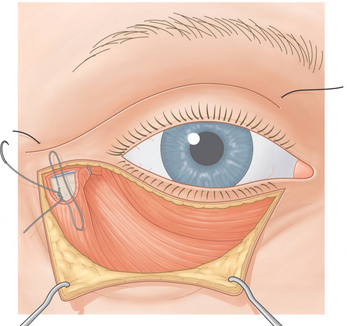

6. Orbicularis oculi muscle suspension

Attention is then directed to the orbicularis muscle flap. Depending on the effect desired 1, 2, or 3 sutures using 4-0 or 5-0 Vicryl on a small P2 half circle cutting needle is used whereby the orbicularis muscle is both plicated and advanced to the lateral orbital rim peri-osteum medially and the temporalis fascia laterally (if applicable) (Figs 15-22, 15-23). One should see the restoration of tension of the lower eyelid orbicularis muscle that raises the eyelid/cheek junction without distracting the lateral commissure and lateral lower eyelid from the globe. This is more easily achieved when the secure lateral retinacular suspension is entirely independent of the orbicularis muscle suspension procedure.

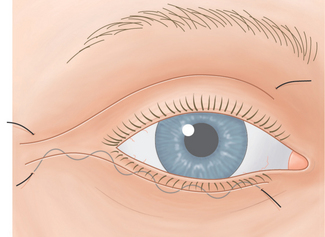

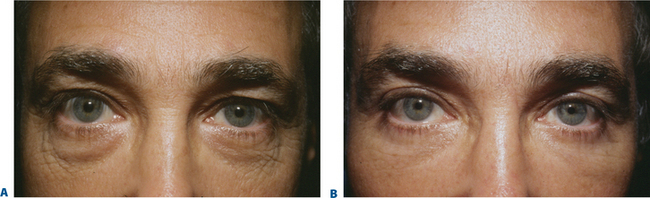

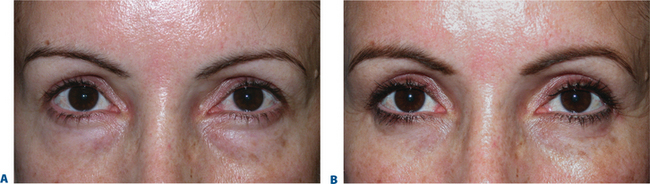

7. Skin redraping, excision, and closure

Once this lateral retinaculum and orbicularis suspension is performed, a very secure lower eyelid and lateral canthus is visualized. Skin redraping is performed. Skin excision can vary from no skin excision to at times significant skin excision depending again on patient presentation (Figs 15-24 to 15-27). Skin closure is performed with interrupted or continuous 6-0 nylon sutures. At times an intramarginal lateral suture tarsorrhaphy is performed to promote good lateral lid position in the immediate postoperative period (Fig. 15-28). After the protective corneal/scleral contact lens is removed the lower eyelid traction suture is then elevated to the suprabrow region with ½ Steri-strip bandages to varying degrees, being sure to allow for at least satisfactory patient vision in the first day, however, elevating the lid to a secure position to facilitate the use of cold compresses by the patient without distorting the lid position (Fig. 15-29).

Figure 15-25 Skin is conservatively redraped and excised so that the edges meet prior to suture placement.

Figure 15-28 A simple suture tarsorrhaphy is seen here at the extreme lateral aspect opposing the upper and lower eyelid.

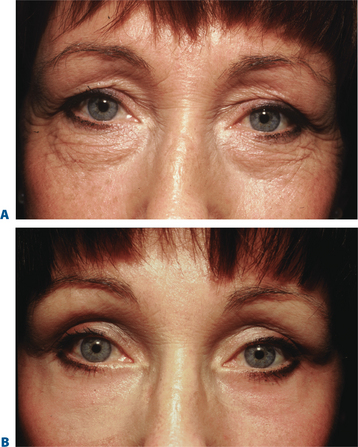

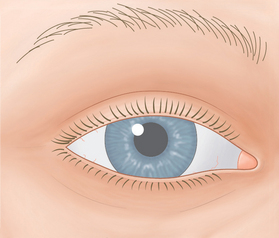

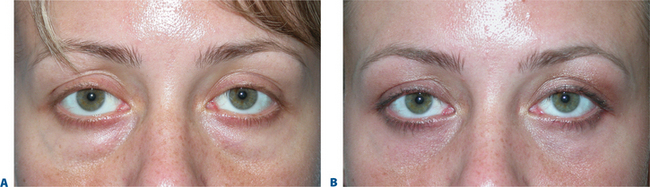

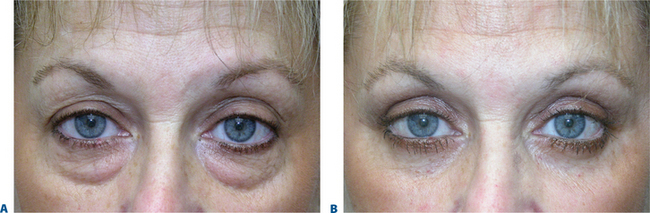

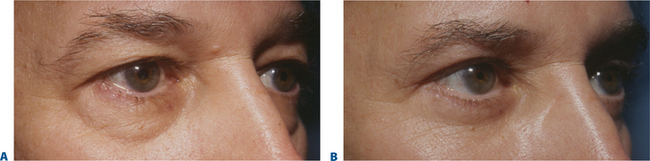

Results with this technique in a variety of patients with different presentations are presented here. The steps in all patients are similar; what is different in each is the degree for which each step is undertaken. For instance, those individuals with minimal skin quality changes require less of a skin flap dissection. Some patients with significant lower eyelid laxity might require the variation of the canthal suspension suture (of heavier gauge, i.e. 4-0 polypropylene), position, or vector of canthal/retinacular support. For instance, a particular orbital configuration and lower eyelid laxity may require the placement/entrance of the suspension suture at the lateral commissure (Fig. 15-10) with supraplacement, in contrast to some individuals with minimal lower eyelid laxity that might be concerned with any change in the lower eyelid slope or canthal position, even short-term. These latter type of individuals might also benefit from a less hearty suture (5-0 polypropylene) without incorporation of the lasso suture (Vicryl) and placement of suture lateral to the commissure without supraplacement. Individuals with significant orbicularis descent and/or with a prominent malar bag might require significant dissection and release of the retaining ligaments and orbicularis muscle, where others with minimal descent might require the minimum dissection and fixation.

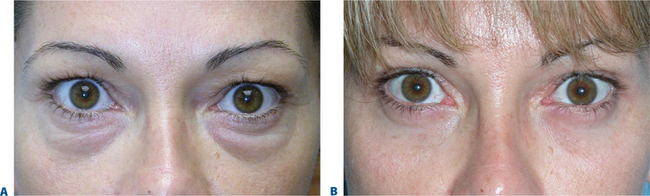

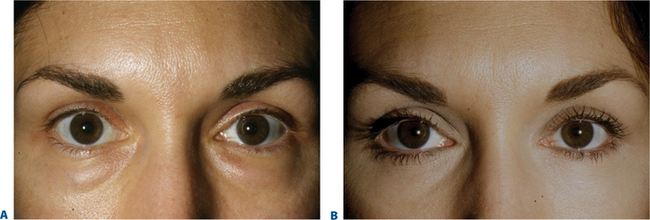

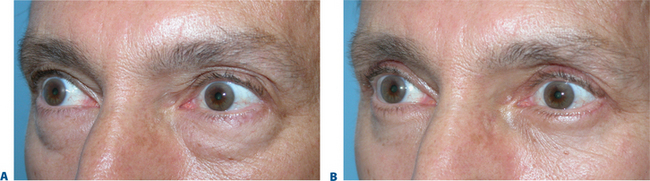

Delivering the best possible result depends on the ability to detect the individual’s situation at hand and deliver with precision the effects that will most accurately restore the youthful complement (Figs 15-30 to 15-46).

Figure 15-34 Oblique views of patient in Fig. 15-33. Note the elevation of the lower eyelid/cheek junction provided by orbicularis oculi muscle suspension.

1 Anderson RL, Gordy DD. The lateral tarsal strip procedure. Arch Ophthalmol. 1979;97:2192.

2 Tenzel RP. Surgical treatment of complications of cosmetic blepharoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. 1990;5:517.

3 Baylis HI, Long JA, Groth MJ. Transconjunctival lower eyelid blepharoplasty. Technique and complications. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:1027.

4 Fitzpatrick RE, Goldman MP, Satur NM, Tope WD. Pulsed carbon dioxide laser resurfacing of photoaged skin. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132:395.

5 Alster TS, Lewis AB. Dermatologic laser surgery. A review. Dermatol Surg. 1996;22:797.

6 Fagien S. Lower-eyelid rejuvenation via transconjunctival blepharoplasty and lateral retinacular suspension. A simplified suture canthopexy and algorithm for treatment of the anterior lower eyelid lamella. Oper Tech Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;5:121.

7 Flowers RS. Canthopexy as a routine blepharoplasty component. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:351.

8 Jelks GW, Jelks EB. Repair of lower lid deformities. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:417-425.

9 Fagien S. Algorithm for canthoplasty: The lateral retinacular suspension: A simplified suture canthopexy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999;103:2042.

10 Mendelson BC, Muzaffar AR, Adams WP. Surgical anatomy of the mid-cheek and malar mounds. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:890.

11 Stuzin JM, Fagien S, Lambros VS. Surgical anatomy of the ligamentous attachments of the lower eyelid and lateral canthus. Surgical anatomy of the mid-cheek and malar mounds by Mendelson BC, Muzaffar AR, Adams WP. [Discussion] Plast Reconstr Surg. 2002;110:905.

12 Flowers RS, Nassif JM, Rubin PAD, Hayakawa T, Lehr SK. A key to canthopexy: The tarsal strap. A fresh cadaveric study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2005;116:1752.