Problem 16 Lower abdominal pain in a 77-year-old woman

Investigation 16.1 Summary of results

| pH | 7.2 (7.38–7.43) |

| pCO2 | 36 mmHg (35–45) |

| HCO3 | 16 (20–24) |

| Lactate | 1.42 (0.50–2.00) |

| Base excess | −9.3 (−3.3–1.2) |

| K | 3.5 (3.8–5.0) |

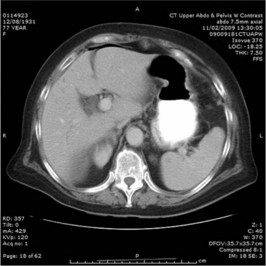

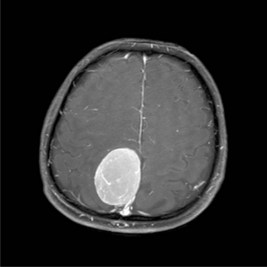

A CT scan of the abdomen is performed. Two representative films are shown in Figures 16.1 and 16.2.

Answers

A.5 The CT images show signs of complicated diverticultis with perforation. In Figure 16.1 multiple diverticuli in the sigmoid colon are present, and free air is visible between the liver and diaphragm in Figure 16.2. Other views show inflammation of the pericolic fat and mesentery of the sigmoid colon with locules of free air in the paracolic gutter.

The CT confirms the suspected diagnosis of diverticulitis with perforation.

Revision Points

The CT scan can rapidly assess the severity of complicated diverticulitis.

Myers E., Hurley M., O’Sullivan G.C., et al. Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage for generalized peritonitis due to perforated diverticulitis. British Journal of Surgery. 2008;95:97-101.

Ooi K., Wong S.W. Management of symptomatic colonic diverticular disease. Medical Journal of Australia. 2009;190:37-40.

Shaikh S., Krukowski Z.H. Outcome of a conservative policy for managing acute sigmoid diverticulitis. British Journal of Surgery. 2007;94:876-879.