Low Anterior Resection with Total Mesorectal Excision and Anastomosis

Surgical Principles

The current standards of care for patients with low rectal cancer include complete excision of the rectum and surrounding mesorectum, generally ensuring a minimal distal margin of 2 cm before a coloanal anastomosis is performed. In general, this procedure is performed in conjunction with a high ligation of the inferior mesenteric artery and vein and mobilization of the splenic flexure (see Chapter 22). The autonomic nerves are carefully protected. Patients with colon cancer require a minimum 5-cm proximal and distal margin, with at least 12 lymph nodes being harvested in the mesocolic excision. Patients with rectal cancer require a 1- to 2-cm margin depending on anatomy, tumor location, and tumor differentiation.

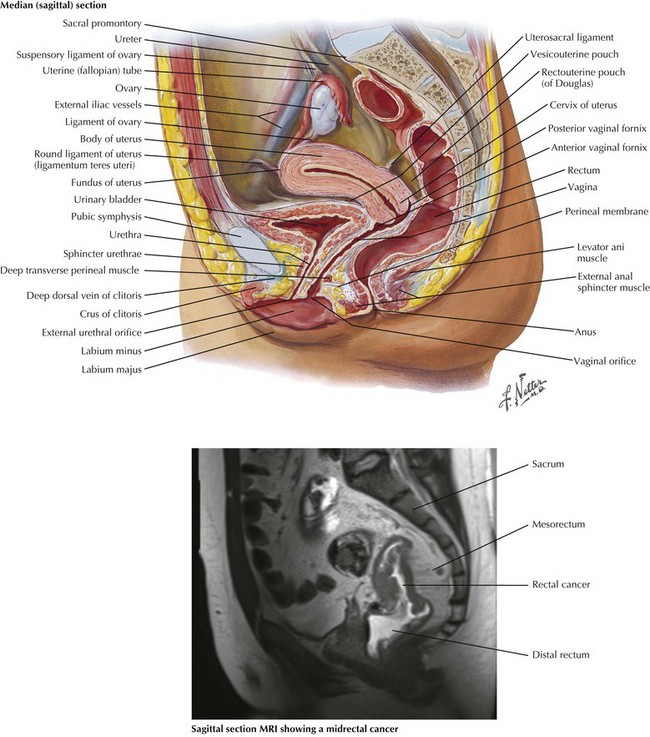

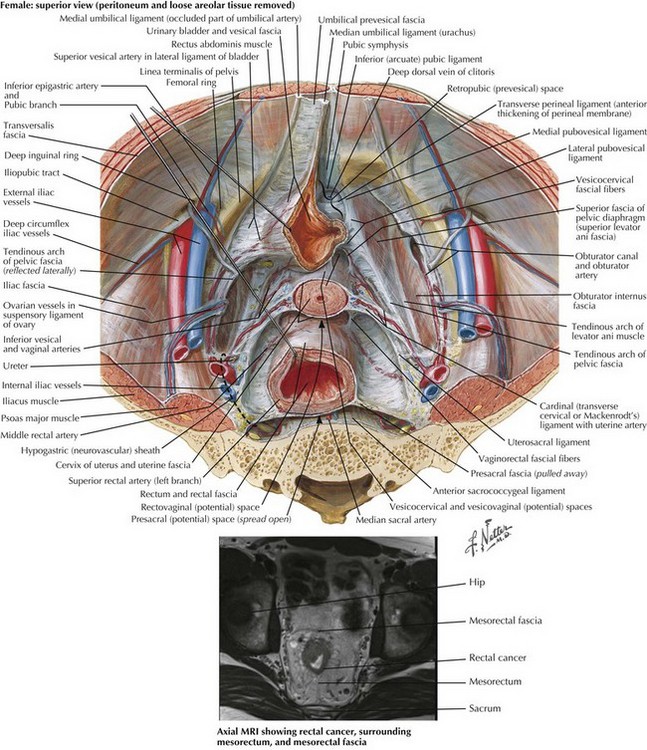

Anatomy for Preoperative Imaging

Preoperative imaging of rectal cancer is extremely important and helps define tumors that may threaten the circumferential resection margin, therefore requiring preoperative chemoradiation. Both sagittal and coronal views are obtained, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is used more frequently because of the high-quality resolution obtained (Figs. 24-1 and 24-2). Ultrasound is also used in the assessment of rectal cancer and can provide excellent results for T staging (tumor infiltration), particularly of early T-stage lesions.

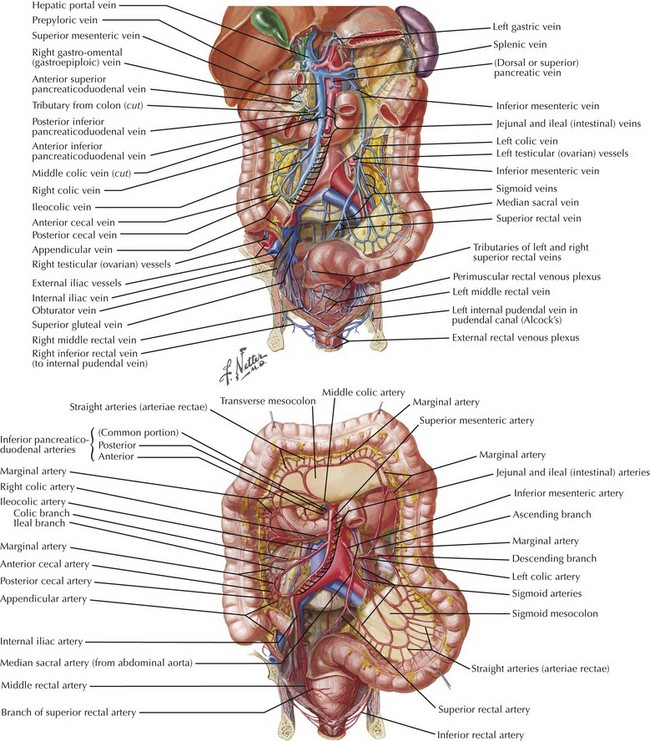

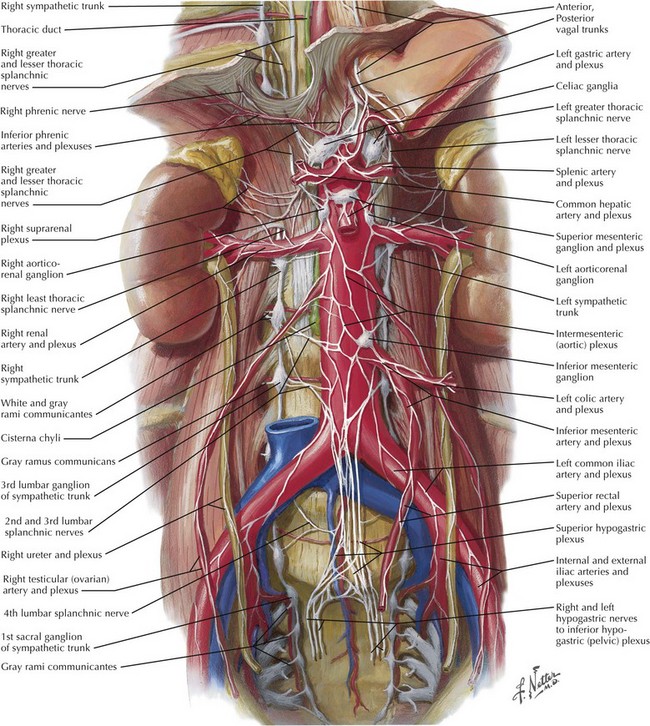

Anatomy for Colonic Mobilization and Dissection

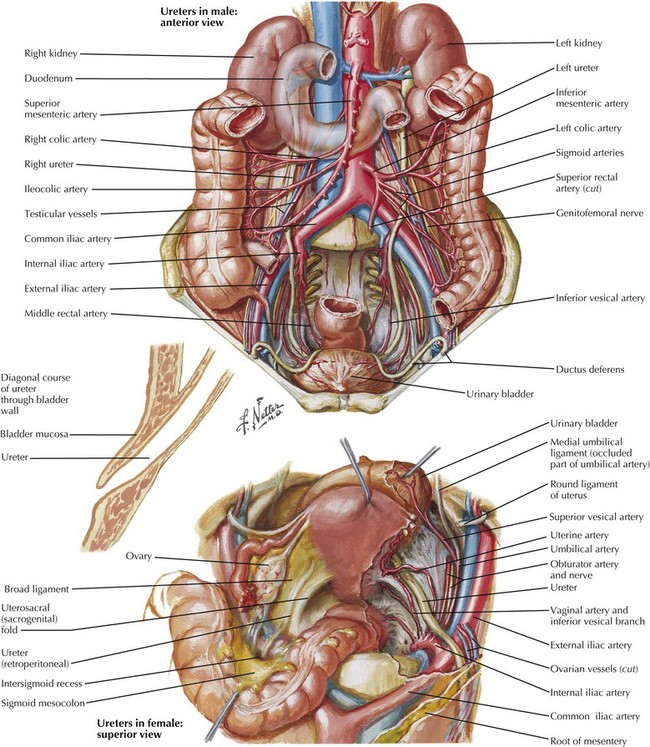

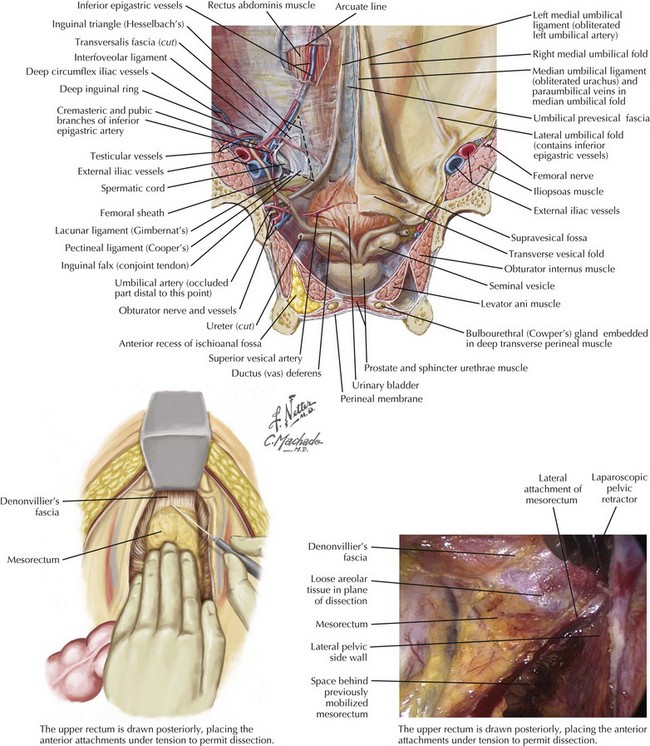

The anatomy of the vascular supply to the colon is demonstrated in Figure 24-3. A knowledge of these vessels, the autonomic nerves, and the ureters is required before the surgeon begins the steps of the procedure (Figs. 24-4 and 24-5).

Inferior Mesenteric Artery and Vein: Anterior View

The sigmoid colon may be mobilized starting on the medial or the lateral side. When the correct planes are defined, Toldt’s fascia is carefully preserved and remains as a parietal layer over the retroperitoneum. The ureters and para-aortic autonomic nerves are by definition posterior to this layer. The mesentery of the distal sigmoid is then elevated from the retroperitoneum under slight tension. The peritoneum to the right of the inferior mesenteric artery (IMA) is opened parallel to the vessel, allowing the index finger of the left hand to encircle the origin of the IMA (Fig. 24-6).

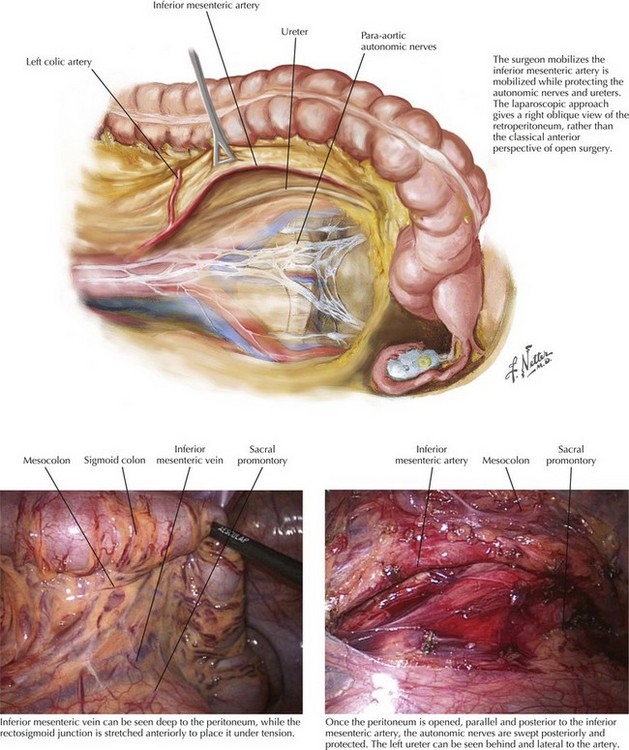

Inferior Mesenteric Artery and Vein: Medial Oblique View

The same anatomy is approached differently in laparoscopic surgery. The position of the camera means that the perspective of the vessels is from a much more oblique view. Nevertheless, the same structures can be observed. When the IMA is divided, this is performed 2 cm distal to its origin to protect the para-aortic autonomic nerves, but proximal to the left colic artery. The IMA is then divided again just below the takeoff of the left colic artery, thereby preserving the left colic’s bifurcation to maximize blood flow to the segment of bowel that will be used as the neorectum (Fig. 24-7).

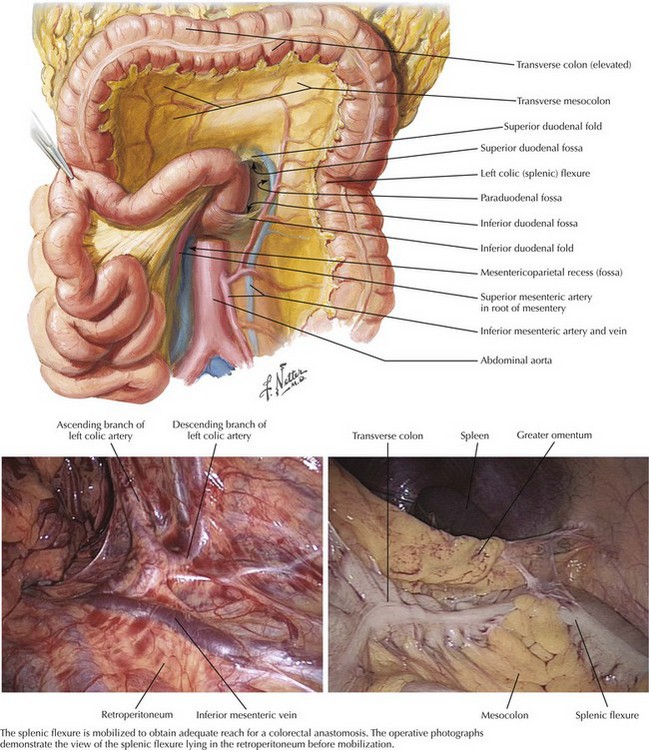

Splenic Flexure

The greater omentum is then elevated superiorly, demonstrating the avascular plane between this and the transverse colon. This plane is opened, mobilizing the splenic flexure so that the colon to the left of the midline is fully freed from its attachments. At this stage the colon is tethered by the inferior mesenteric vein (IMV) as it enters the splenic vein behind the pancreas. The IMV is divided just below the pancreas, giving several extra inches of reach to allow the descending colon to reach into the pelvis (Fig. 24-7).

Anatomy for Rectal Mobilization and Dissection

The anatomy of the dissection of the upper rectum is demonstrated in Figure 24-6, along with the pelvic autonomic nerve anatomy. Knowledge of these vessels and the autonomic nerves is required before beginning the pelvic dissection.

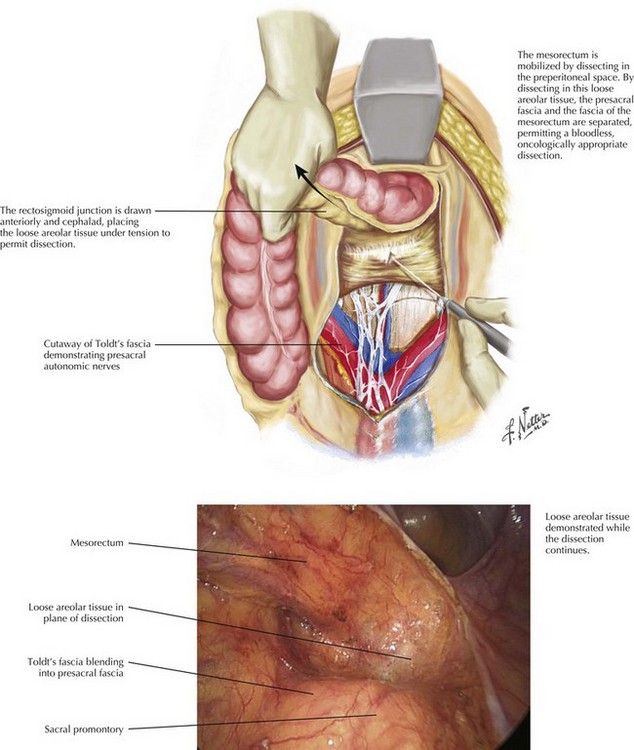

Upper Mesorectum: Posterior Mesorectal Anatomy

Dissection commences behind the rectum, staying between the plane of the parietal peritoneum and the fascial layer investing the mesorectum. The initial dissection is in the midline posteriorly and continues down to the level of the levator muscles, demonstrating the bilobed appearance of the intact mesorectum. Adequate distraction of tissues assists in demonstration of the correct anatomic planes. Dissection continues laterally on both sides until the rectum becomes tethered by the anterior peritoneal attachments at the pouch of Douglas (Fig. 24-8).

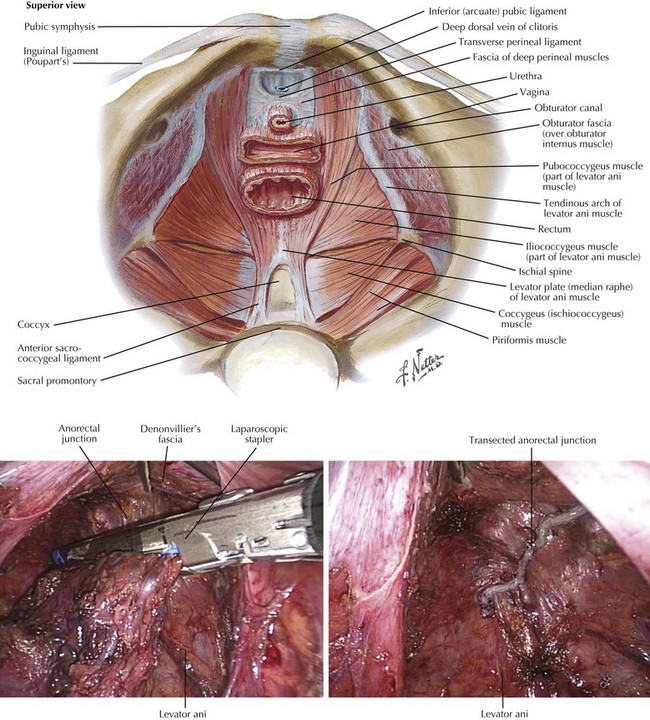

Lower Mesorectum: Anterior Mesorectal Anatomy

The bladder or uterus is then drawn anteriorly, and cautery is used to continue the lateral dissection anteriorly, opening the peritoneum immediately behind Denonvilliers’ fascia. The dissection then continues distally until the levators are seen to curve distally into the anal canal, protecting the anterolateral neurovascular bundles (Fig. 24-9).

Rectal Transection from Above

Once an adequate distal margin has been obtained, the rectum may be transected below the level of the tumor, usually at the anorectal junction. At this level there is no mesorectum to divide, and a stapler fits easily around the rectum. The specimen is amputated and removed from the field. This approach leaves a transverse staple line that can be easily seen from above, sitting just into the upper anal canal within the sling of the levators, ready for a stapled coloanal anastomosis (Fig. 24-10).

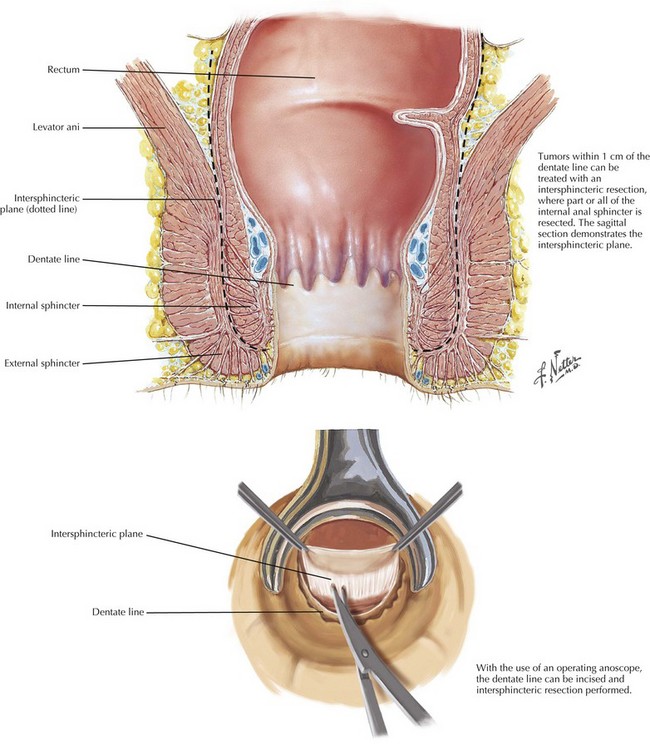

Rectal Transection from Below

Some patients have insufficient distal margin for a stapled anastomosis, usually less than 1 or 2 cm from the dentate line. In these cases the intraabdominal dissection proceeds as previously described until the anal canal is reached. At this stage the surgeon moves to the perineum. An operating anoscope is used to visualize the dentate line, which is incised circumferentially with cautery. The dissection is continued to the internal sphincter, which is transected circumferentially. An intersphincteric dissection is then performed joining the prior plane of dissection from above (Fig. 24-11).