6 Locomotion

Introduction

History

Table 6.1 Important features of a ‘locomotor’ or ‘musculoskeletal’ history

| Presenting symptom | |

|---|---|

| Joints | Pain – where, when is it worst, does it wake the child at night, what brings it on, is there anything that improves it? Swelling Morning stiffness (this is different from pain) – ‘It takes her an hour to get going and then she loosens up’ Function – unable to weight bear, cannot do up buttons Joint distribution |

| Extra-articular | Fever Rash, hair loss, mouth ulcers Poor appetite Weight gain and growth Vision |

| Past history | Any precipitating or preceding illness Development |

| Family history | Complete family tree Ask especially about arthritis, psoriasis, systemic lupus erythematosus, maternal miscarriages, inflammatory bowel disease |

| Social | Functional ability – dress, feed, walk, etc. ‘Is there anything that you want to do but can’t?’ School – ability and progress ‘What are you into?’ – can the child still do everything they wish to do, and as well as their peers? |

Examination

Table 6.2 lists important features of the musculoskeletal examination. Remember the mnemonic GALS (gait, arms, legs, and spine).

| Gait | The child must be in underwear/minimal clothing to observe lower limbs and spine fully Preserve dignity Look at position of knees, ankles and feet, freedom of movement |

| Joint (any) | Inspect – skin colour, muscle bulk, resting position Palpate – skin warmth, joint swelling (soft tissue, bone, intra-articular effusion), site of maximal tenderness, tendons Move – range of active and passive movement |

| Hands | Pattern of joint involvement, rashes, nails (pitting in psoriasis, nail fold infarcts in vasculitis) Can she make a fist with the distal phalanges tucked perpendicular to the palm? What is the grip like? Does the thumb oppose to the base of the fifth finger? |

| Arms (sitting up) | ‘Put your arms out straight, now turn your hands over’ (elbow extension, supination/pronation), ‘put your hands behind your head’ (glenohumeral and sternoclavicular movement), ‘stretch your hands to the ceiling’ (proximal muscle strength) Move joints passively through their full range |

| Feet (lying down) | ‘Point your toes down, then bend them up’ (ankle joint) Squeeze the metatarsophalangeal joints (gently) – for synovitis pain Test eversion and inversion of the heel and forefoot (subtalar and mid-tarsal joints) |

| Legs (lying down) | Normal muscle bulk? Any swelling, deformity? Equal leg length? – measure real and apparent shortening ‘Hug your right knee into your chest’ (knees and hips) then the left Check for knee effusion: compressing the bursa above the patella, gently press the patella with the other hand – does it bounce off the distal femur? If you stroke up the medial side of the knee, down the lateral side, can you see fluid bulging from side to side? (effusion) |

| Legs (standing) | Any valgus or varus deformity? (valgus – the distal part of the limb is angled away from the midline; varus – the limb is angled towards the the midline) Flat feet (loss of the medial longitudinal arch)? If so, get the child to stand on tip-toe – can you see the arch now? |

| Spine (standing) | Stand behind the child and look at how straight the spine is and whether the normal curves are present ‘Bend forward to touch your toes’ – this should result in a smooth curve with no lateral deviation (scoliosis) Observe the neck movements (forward and lateral flexion, extension, rotation) |

Principles of management

You should work towards recovery with appropriate therapy, including medication, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, orthotics and psychological support. The child and family need education and support about the condition, the impact on school and family life, and, very often, financial support (disability living allowance). Social services and voluntary organizations may be able to help (see also Chapter 3).

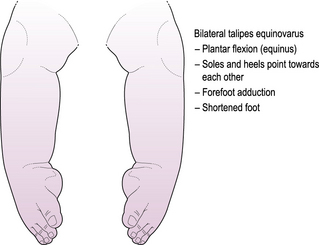

Packaging defects

Pigeon toed (in-toeing)

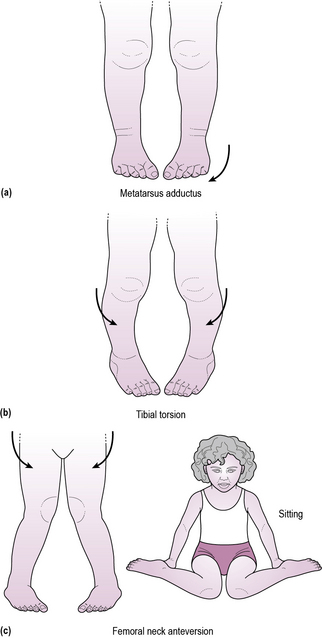

There are three main causes of an in-toeing gait, which relate to the anatomical site of the abnormality (Figure 6.2):

1. The forefeet may point inwards (metatarsus adductus or varus); this commonly presents from birth to 5 years and slowly rights itself. Children are only noted to in-toe with their shoes off.

2. Medial tibial torsion will result in the top part of the tibia pointing forwards, whilst the bottom points inwards. This is common with bow-legs and usually corrects by about 5 years.

3. Children with persistent anteversion of the femoral neck commonly sit with knees bent and feet at either side of their hips. This is comfortable because internal rotation of the hip is easy, and external rotation is usually mildly reduced (difficulty sitting cross-legged). It normally corrects itself by 8 years.

Toe-walking

This is common and normal if it starts early and involves both feet with normal balance and manoeuvrability. The child can walk with feet flat if asked to do so. A careful examination to exclude cerebral palsy is important (see Chapter 14, p. 197).

The limping child

Transient synovitis of the hip

Case 6.1 describes the classical presentation of transient synovitis, which is the most common cause of acute hip pain in children. It occurs most often in boys (70%) in the 3–10-year age group and usually accompanies or follows a viral infection. Presentation is with acute-onset pain or limp. Pain may be referred to the thigh or knee. The child is not normally unwell, and is usually comfortable at rest. There may be a mild temperature and a decreased range of movement of the hip, particularly internal rotation.

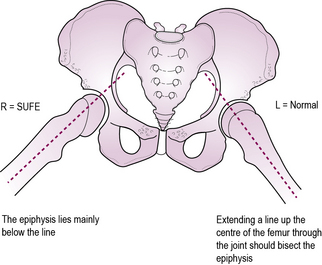

Developmental dysplasia of the hip

Although a cause of limp, this condition should normally be detected after birth on routine neonatal examination (see Chapter 17, p. 248); however, late presentations with a limp do occur. DDH represents a spectrum of disorders ranging from hip dysplasia, through subluxation to frank dislocation. The prevalence of the condition is about 1.5:1000 and is commoner in girls. Screening examination, with Barlow’s and Ortolani’s tests (see Figure 6.5), should enable early diagnosis and treatment with normal subsequent joint development. If the screening examination is abnormal the baby should have an ultrasound scan, which will give a detailed assessment of both the hip and the acetabulum. If hip dysplasia is confirmed, treatment should be supervised by a paediatric orthopaedic surgeon and physiotherapist. The infant will be put in a splint (usually a Pavlik harness, fitted expertly by paediatric physiotherapists), which maintains about 60° abduction and 90° flexion of the hip, but allows kicking of the lower leg. This maintains the femoral head within the acetabulum and allows each to grow normally. It may be required for 8–12 weeks and must be carefully monitored for fit as the child grows.

The painful leg

Acutely painful limb – trauma

Children are frequently brought to the A&E department with a painful limb with a history of trauma. By and large, ‘sprains’ do not happen in young children, and if the child cannot weight bear or is unable to use the arm, the likelihood is that there is a fracture, and an X-ray is mandatory. Always consider carefully how the injury was said to have occurred and whether this is consistent with the findings (see Chapter 5) as non-accidental injury is an important differential diagnosis.

Arthritis

‘My child has swollen, painful joints’

In contrast, inflammatory polyarthritis is worse after a period of inactivity, and so is particularly bad in the morning. It may take some time for the joints to ‘loosen up’ in the morning (morning stiffness). On examination, finding erythema, heat, tenderness, a restricted range of movement, soft-tissue swelling or a joint effusion confirms inflammation. The causes of polyarthritis are shown in Table 6.3.

| Category | Diagnoses |

|---|---|

| Infection | Bacterial – septicaemia/septic arthritis, TB Viral – adenovirus, coxsackie B, parvovirus, etc. Reactive arthritis Rheumatic fever Lyme disease |

| Juvenile idiopathic arthritis | See under ‘Juvenile idiopathic arthritis’ |

| Connective tissue disorder | Systemic lupus erythematosus Dermatomyositis |

| Inflammatory bowel disease | Crohn’s disease Ulcerative colitis |

| Vasculitis | Henoch–Schönlein purpura Kawasaki’s disease |

| Haematological disorders | Haemophilia Sickle-cell disease |

| Malignant disorders | Leukaemia |

| Other | Cystic fibrosis |

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis

History

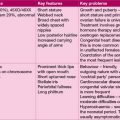

JIA presents in various clinical patterns (Table 6.4). Children and their parents are concerned about the prognosis rather than the label, but the prognosis depends on the type of JIA. Ask about psoriasis.

| Type of JIA | Features | Prognosis |

|---|---|---|

| Oligoarthritis (60%) | Girls:boys 5:1, age 6 months to 6 years with 1–4 joints involved | Remission in 4–5 years usual One-third extend to polyarthritis |

| Polyarthritis (24%) | Girls aged 10–14 years with more than 4 joints involved | If rheumatoid factor positive, destructive and aggressive |

| Enthesitis related (7%) | Boys aged 10–14 years large joint arthritis and enthesitis common | Up to 60% develop ankylosing spondylitis |

| Systemic (‘Still’s disease’) (9%) | Boys or girls aged 2 years Fever, malaise, salmon-pink flitting rash, hepatosplenomegaly, lymphadenopathy |

Most remit after 3–5 years |

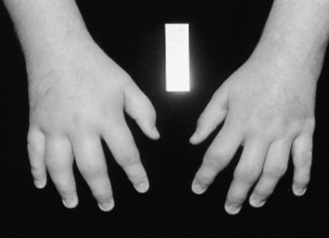

Examination

This must include all the systems, since the disease can involve any system and extra-articular features provide helpful clues to aetiology. Each joint should be assessed in turn, including the often forgotten temporomandibular joints, and spine. See Figure 6.6 for the signs of JIA in the hands.

Complications

All children should be screened by regular slit-lamp examination for anterior uveitis, which is often asymptomatic. The autoantibody status should be checked because those who are antinuclear antigen positive are particularly likely to develop anterior uveitis (see Chapter 14, p. 212). In oligoarthritis, overgrowth of the bones surrounding the active joint may result in leg length discrepancy. Flexion contractures of joints may occur because the joint is held in the most comfortable position. Chronic disease can lead to joint destruction and the need for joint replacement. Osteopenia and growth failure may occur because of immobility, chronic disease and steroid use. Amyloidosis is, thankfully, rare.

Henoch–Schönlein purpura

This is a post-infective vasculitis (see also Chapter 11, pp. 127–128). There is often a preceding history of an upper respiratory tract infection. It peaks during the winter and is twice as common in boys, usually between 3 and 10 years old. The child presents with a rash, commonly on the extensor surfaces of the arms, legs and across the buttocks, which is initially erythematous, then maculopupular and non-blanching (purpuric). There is often a fever. Joint pain occurs in two-thirds, particularly of the knees and ankles. There is often peri-articular oedema, rather than joint effusions. Colicky abdominal pain occurs in many children, and bleeding into the gastrointestinal tract may result in melaena. Intussusception is a rare complication. Renal involvement is common with 80% showing microscopic haematuria. Treatment is supportive. The blood pressure should be checked and urinalysis repeated until normalized. If the haematuria worsens, or proteinuria develops, a nephrologist should be consulted (see Chapter 11, p. 128).

Other patterns of limb pain

Chronic limb pain

If there is anything atypical about the history or examination, routine bloods and X-rays should be done in order to rule out a bone tumour (osteosarcoma and Ewing’s tumour), or leukaemia (see Chapter 7). Bone tumours are rare and usually present with pain and swelling or occasionally pathological fracture.

Rheumatic fever

This is a form of reactive arthritis, and, although rare in the UK, is a major cause of heart failure in the developing world because of resultant mitral valve disease (see also Chapter 9, p. 98). It is a post-streptococcal disorder characterized by a migratory transient arthritis, a skin rash, carditis, subcutaneous nodules and occasionally chorea. Treatment of streptococcal throat infections with penicillin has dramatically reduced the incidence in the developed world. The major and minor criteria are shown in Table 6.5. To make a diagnosis, two major criteria, or one major and two minor criteria, are required with supporting evidence of preceding group A streptococcal infection.

Table 6.5 The Jones criteria for diagnosis of rheumatic fever

| Major | Sydenham’s chorea 10% |

| Nodules (subcutaneous) | |

| Arthritis 80% | |

| Karditis 50% (carditis) | |

| Erythema marginatum 5% | |

| Minor | Fever |

| Arthralgia | |

| Prolonged P–R interval on ECG | |

| Raised CRP and ESR | |

| Past history of rheumatic fever |