CHAPTER 5 Locally Advanced Breast Cancer (LABC) and Neoadjuvant Chemotherapy

DEFINITION OF LOCALLY ADVANCED BREAST CANCER

The definition of locally advanced breast cancer (LABC) has continued to evolve since Haagensen and Stout outlined their criteria for operability more than 60 years ago.1 Their conclusions remain a part of the current American Joint Committee on Cancer Classification System for LABC, as depicted in Table 1. LABC includes large tumors (>5 cm), those (of any size) with involvement of the skin or chest wall, and those with clinically apparent axillary nodal involvement (matted or fixed) or ipsilateral internal mammary, infraclavicular, or supraclavicular nodal disease.

Table 1 Primary Tumor (T) and Clinical Regional Lymph Node (N) Categories Comprising LABC in the Current American Joint Committee on Cancer Classification System

| T3 | Tumor >5 cm in greatest diameter |

| T4 | Tumor of any size, with direct extension to chest wall or skin, as described below |

| T4a | Extension to chest wall, not including pectoralis muscle |

| T4b | Edema (including peau d’orange) or ulceration of the skin of the breast or satellite nodules confined to same breast |

| T4c | Both Ta and Tb |

| T4d | Inflammatory carcinoma |

| N2 | Metastases in ipsilateral axillary nodes fixed or matted, or in clinically apparent ipsilateral internal mammary nodes in the absence of clinically evident axillary node metastases. |

| N3 | Metastases in ipsilateral infraclavicular or supraclavicular lymph nodes or in clinically apparent internal mammary nodes in the presence of clinically evident axillary node metastases. |

Data from Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed. New York, Springer Verlag, 2002.

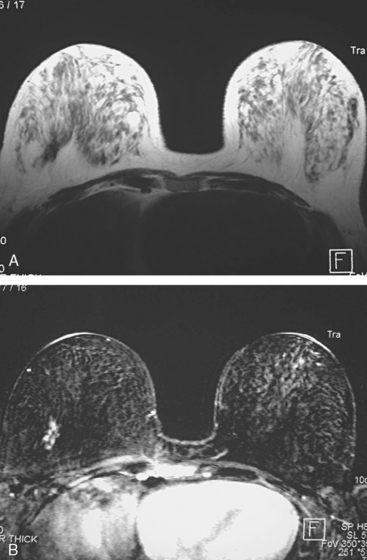

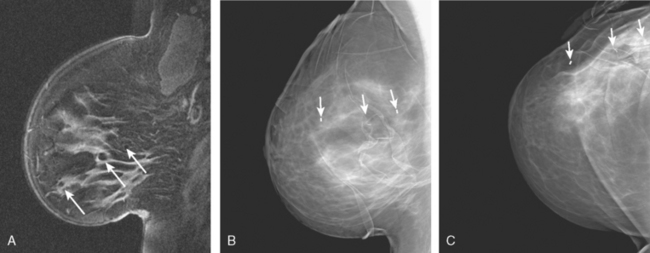

ASSESSMENT OF PATIENTS SUSPECTED TO HAVE LABC

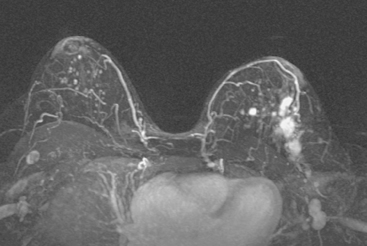

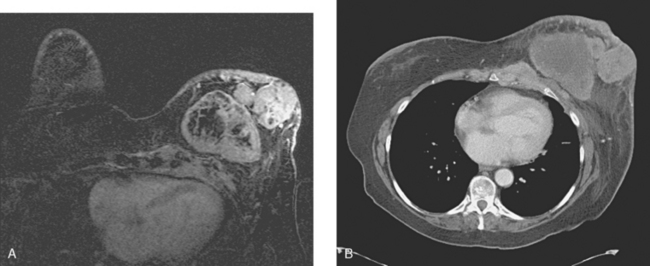

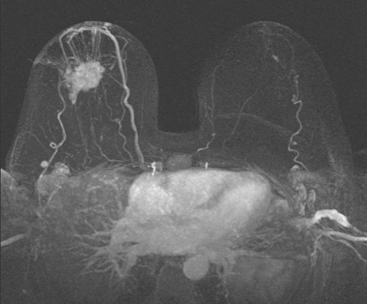

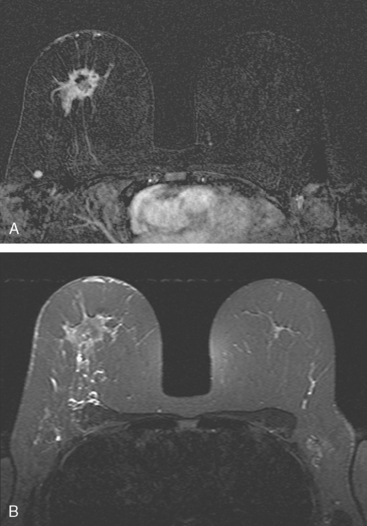

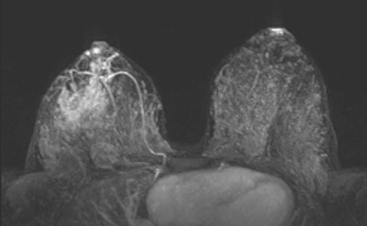

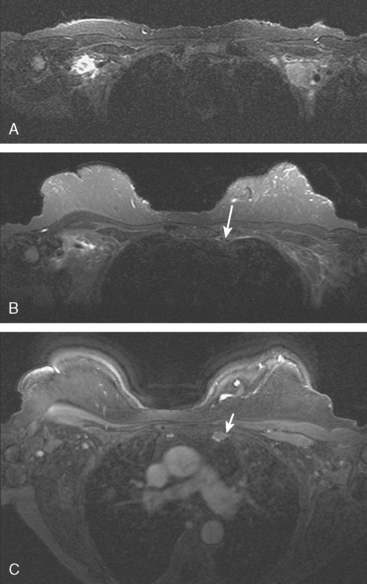

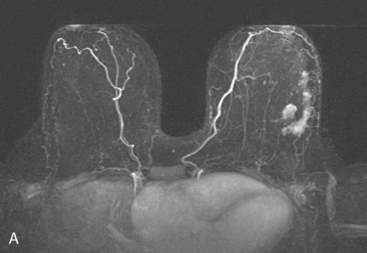

Locoregional staging of breast cancer is covered in depth in Chapter 3, including assessment with mammography, ultrasound, and MRI. The principles outlined in that chapter are identical for the patient who meets the definition of LABC. MRI has proved extremely valuable in accurately estimating tumor size and extent, as well as determining multifocality, multicentricity, and bilaterality (Figure 1). MRI more accurately correlates with tumor size and number of tumors at pathology than mammography or ultrasound. It is the modality of choice for assessment of chest wall invasion (Figure 2).

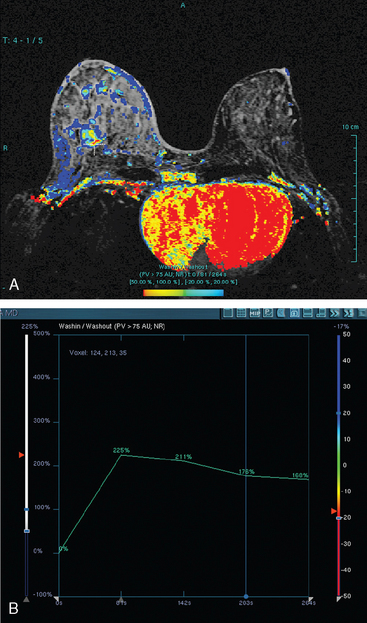

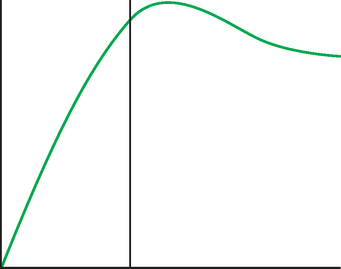

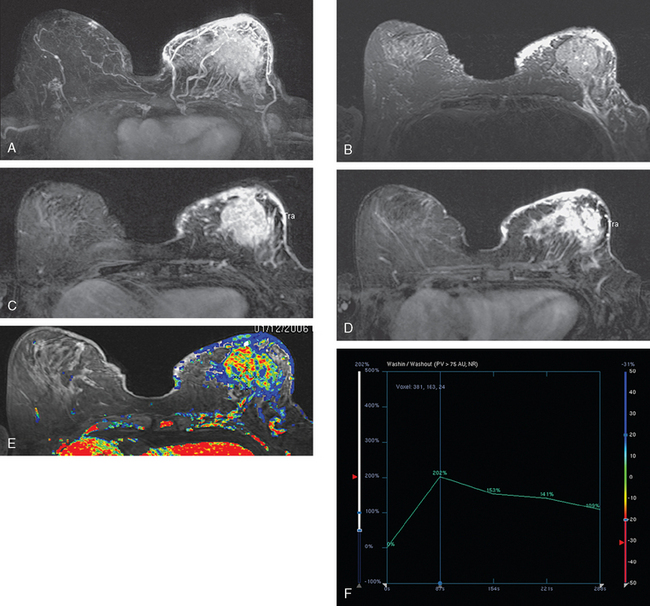

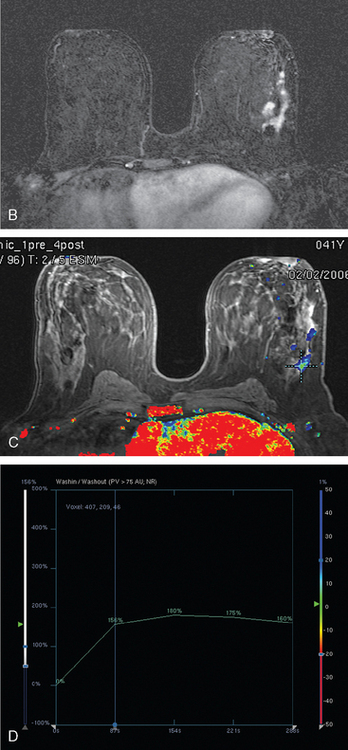

ASSESSMENT OF RESPONSE TO NEOADJUVANT CHEMOTHERAPY

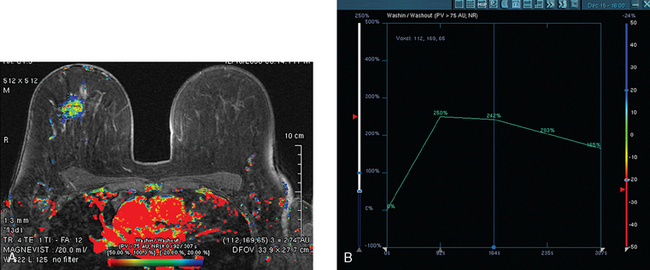

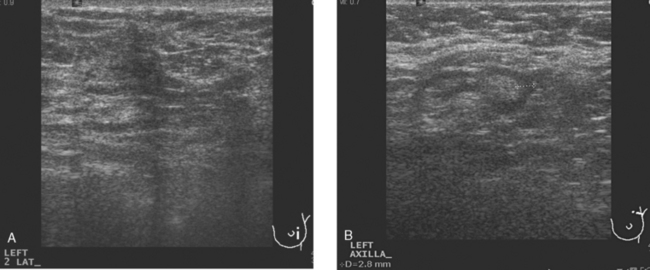

Assessment of response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy with anatomic imaging modalities can be problematic. On mammography, breast cancers that initially manifest as masses generally decrease in size in response to chemotherapy, but may not completely resolve. Breast cancer manifesting on mammography as microcalcifications is even more difficult to accurately assess in terms of responsiveness to neoadjuvant therapy because microcalcifications may not resolve, even in responders. On ultrasound, responding tumors show a decrease in size and, occasionally, resolution. MRI appears to be the most reliable anatomic imaging modality in common use today for monitoring patients being treated preoperatively.3–8 In addition to showing decreased tumor size, the enhancement pattern changes in responders. Responding tumors showing intense enhancement and washout initially often show decreased intensity of peak enhancement, as well as more benign patterns of progressive or persistent enhancement (flattening of the enhancement curve). Responding tumors may shrink, retaining a smaller, but still mass-like, morphology, or they can “break apart,” manifesting as less intense, smaller foci of enhancement within the distribution of the initial abnormality. Complete response by MRI (complete resolution of all tumor-associated enhancement) does not confirm a complete pathologic response because some patients with complete imaging responses have microscopic disease at pathology. Conversely, some patients with good, but incomplete, responses by MRI (some residual enhancement in the distribution of the original tumor) prove at pathology to have had complete pathologic responses.

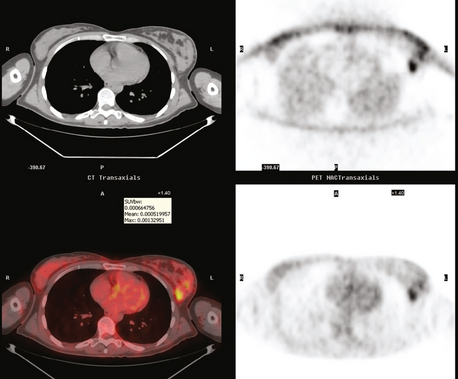

PET and PET/CT are assuming an increasing role in this assessment, and a larger role for breast-specific gamma imaging and positron emission mammography can be anticipated in the future. Quantitative PET assessment, using the standardized uptake value (SUV), has shown early success in separating responders from nonresponders.10–12 Careful attention must be paid to all the factors influencing SUV measurement, especially region-of-interest assignment and patient glucose level. Flare responses (increased uptake as a manifestation of response), which can be seen on PET with initiation of tamoxifen therapy, are not seen with chemotherapy.

ASSESSMENT OF SENTINEL NODE STATUS IN LABC TREATED NEOADJUVANTLY

A controversial issue in the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy is whether to assess preoperatively the status of the axilla with sentinel lymph node (SLN) sampling. It has been demonstrated that information from SLN biopsy or axillary dissection performed after completion of chemotherapy correlates well with overall prognosis. The role of SLN sampling and axillary dissection in the postchemotherapy setting was reviewed in a meta-analysis, with an overall accuracy of 95%.13

ASSESSMENT FOR SYSTEMIC METASTASES (EXCLUSION OF STAGE IV DISEASE)

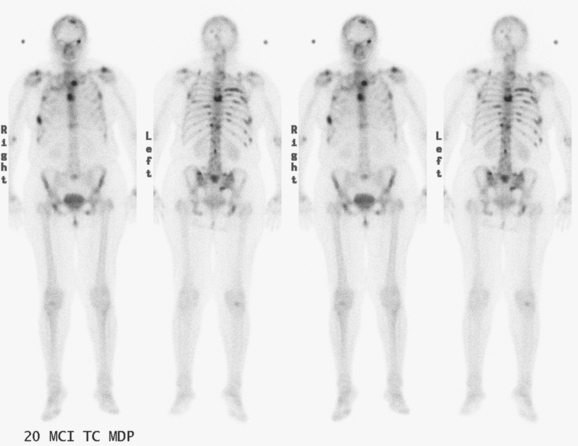

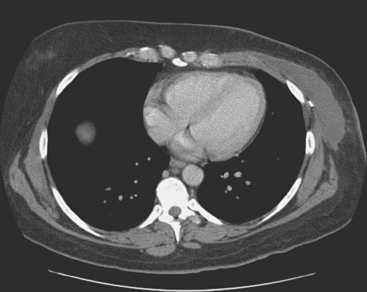

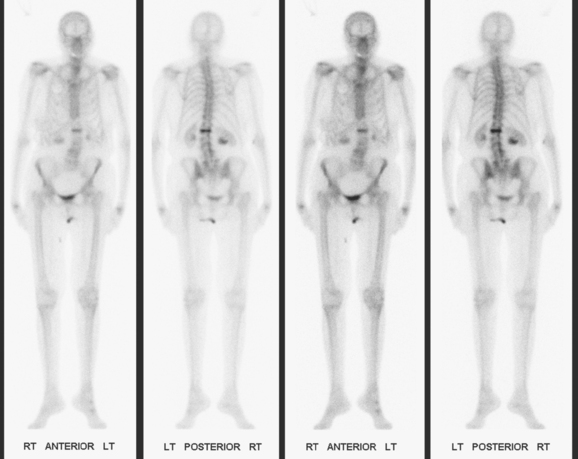

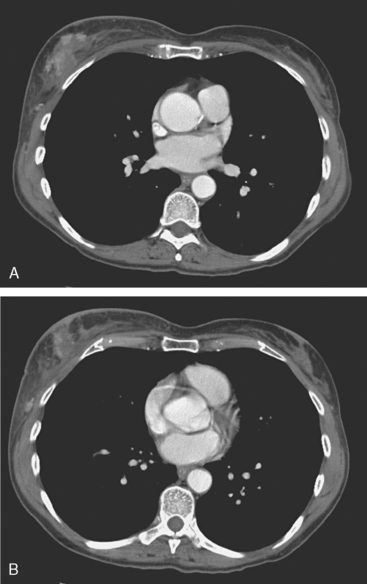

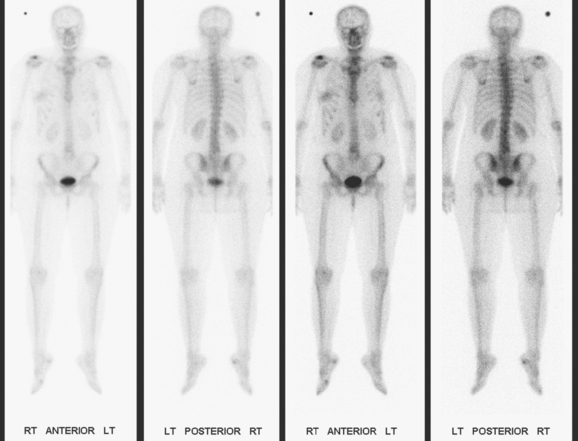

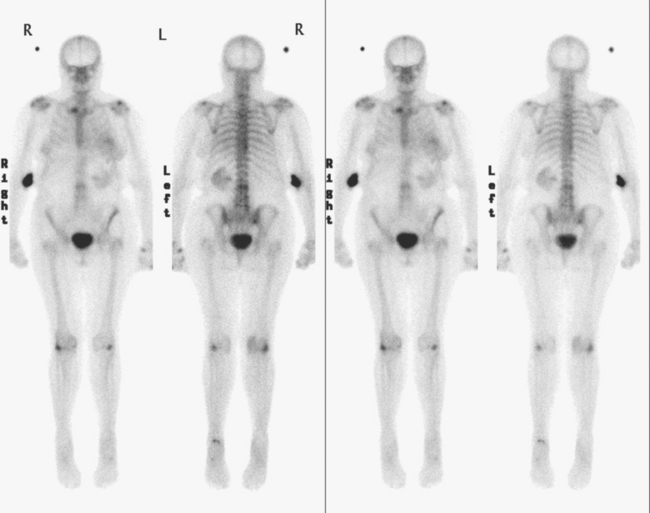

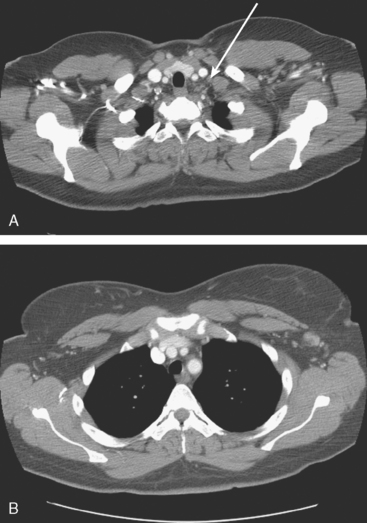

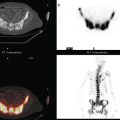

The most common sites of breast cancer metastasis are bone, lung, and liver, in that order.14 Evaluation of bone should begin with a careful history to elicit any symptoms or history of recent trauma. Serum alkaline phosphatase and calcium measurements may be helpful if positive and heighten suspicion of bony involvement. Imaging options, discussed in greater depth in Chapter 8, include bone scanning, CT, MRI, and PET. Bone scintigraphy, using a technetium-based agent (e.g., methylene diphosphonate), is exquisitely sensitive to changes in bone metabolism. Localization of these agents into bone is dependent on many factors, with the most important two being blood flow and osteoblastic activity. This results in a very predictable concentration in osteoblastic metastases (Figure 3). Positive findings on scintigraphy antedate findings on plain radiography by weeks to months. Drawbacks of bone scanning include suboptimal specificity, reduced sensitivity in osteolytic metastases, and persistent positivity at sites where active tumor is no longer present. Additionally, the well-recognized flare phenomenon, resulting in apparent worsening on scintigraphy due to treatment response, may mislead the unaware clinician or imager. Specificity is arguably the most problematic feature of whole-body skeletal scintigraphy. Any process that results in an increase in bone remodeling will demonstrate increased uptake of radiopharmaceutical. For this reason and because of the implications of labeling a patient as having bony metastases, correlative imaging (or even tissue sampling) is required. Correlation can be accomplished with plain radiography, CT, or MRI.

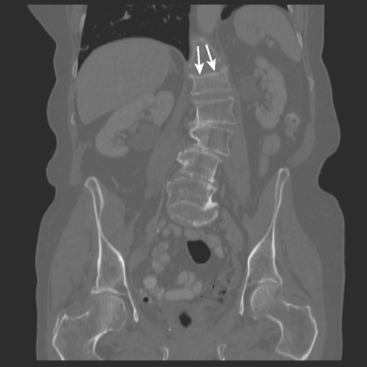

Plain radiography is of minimal value as a screening modality, requiring 30% to 50% loss of bone mineral for a metastasis to become visible.15 Plain radiographic correlation with a scintigraphic abnormality may be of benefit; however, the increased sensitivity and improved anatomic detail (including surrounding soft tissues) are factors favoring CT (Figure 4) or MRI. Although MRI has a higher rate of detection of skeletal metastases than scintigraphy in the spine, pelvis, limbs, sternum, scapulae, and clavicles,16 the logistics and cost of whole-body MRI give scintigraphy the edge as an initial screening examination.

FIGURE 4 Chest CT image, displayed with bone windowing, from the same patient in Figure 3, shows abnormal, mottled, partially blastic bone mineral texture involving a long segment of a right posterior rib, corresponding to the bone scan.

PET and, more recently, PET/CT have been used to evaluate the entire body for metastases, including bone. An emerging consensus is that PET and scintigraphy have a similar sensitivity for detection of metastases, whereas PET shows a definite in-crease in specificity.17–20 There also appears to be a significantly higher sensitivity with fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET for osteolytic metastases. Conversely, bone scintigraphy has shown superiority for demonstration of osteoblastic lesions. Currently, PET and bone scintigraphy are viewed as complementary imaging modalities for the detection of skeletal metastases.

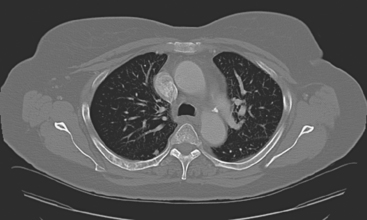

Lung metastases are relatively common in patients with metastatic disease and in those who die from breast cancer. However, lung metastases are very uncommon at initial diagnosis of breast cancer.21 Many centers still recommend a chest x-ray at initial screening (in part, because of the age of their breast cancer population); however, positive findings on chest x-ray generally necessitate CT correlation. CT is the modality of choice for chest evaluation. PET/CT offers advantages over CT alone in evaluating the mediastinum and as a whole-body survey.22

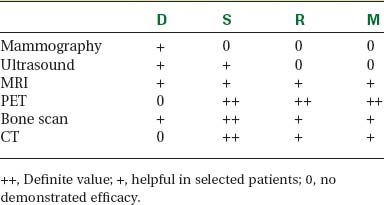

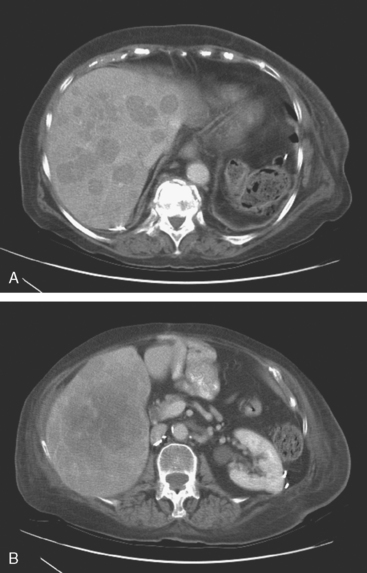

Evaluation of the liver is covered in depth in Chapter 9. In addition to CT, MRI, and PET, ultrasound may be appropriate in selected patients. The number of patients with hepatic metastases at initial presentation is extremely low. Screening, whether using liver enzymes or imaging, is nonspecific and of low diagnostic yield. For symptomatic patients and those with clinical evidence of liver involvement, CT and MRI are considered the imaging modalities of choice.23 Ultrasound may be useful to help characterize small lesions identified on CT.24 Finally, FDG PET is best viewed as complementary in the liver; it carries an excellent specificity and will occasionally find lesions not appreciated prospectively on CT or MRI, but it has limited sensitivity for small lesions (<1 cm) and can be difficult to interpret when there is heterogeneous FDG uptake, which can be exacerbated by attenuation correction (Table 2).

1 Haagensen C, Stout A. Carcinoma of the breast: Criteria of operability. Ann Surg. 1943;118:859-868.

2 Greene FL, Page DL, Fleming ID, et al. AJCC Cancer Staging Manual, 6th ed. New York: Springer Verlag, 2002.

3 Rieber A, Brambs HJ, Gabelmann A, et al. Breast MRI for monitoring response of primary breast cancer to neo-adjuvant chemotherapy. Eur Radiol. 2002;12(7):1711-1719.

4 Partridge SC, Gibbs JE, Lu Y, et al. Accuracy of MR imaging for revealing residual breast cancer in patients who have undergone neoadjuvant chemotherapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2002;179:1193-1199.

5 Rosen EL, Blackwell KL, Baker JA, et al. Accuracy of MRI in the detection of residual breast cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1275-1282.

6 Londero V, Bazzocchi M, Del Frate C, et al. Locally advanced breast cancer: comparison of mammography, sonography and MR imaging in evaluation of residual disease in women receiving neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Eur Radiol. 2004;14(8):1371-1379.

7 Martincich L, Montemurro F, De Rosa G, et al. Monitoring response to primary chemotherapy in breast cancer using dynamic contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2004;83(1):67-76.

8 Yeh E, Slanetz P, Kopans DB, et al. Prospective comparison of mammography, sonography, and MRI in patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy for palpable breast cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(3):868-877.

9 Bassa P, Kim EE, Inoue T, et al. Evaluation of preoperative chemotherapy using PET with fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose in breast cancer. J Nucl Med. 1996;37(6):931-938.

10 Schelling M, Avril N, Nahrig J, et al. Positron emission tomography using [(18)F]-fluorodeoxyglucose for monitoring primary chemotherapy in breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18:1689-1695.

11 Biersack HJ, Palmedo H. Locally advanced breast cancer: is PET useful for monitoring primary chemotherapy? J Nucl Med. 2003;44(11):1815-1817.

12 Rosen EL, Eubank WB, Mankoff DA. FDG PET, PET/CT, and breast cancer imaging. RadioGraphics. 2007;27:S215-S229.

13 Xing Y, Ding M, Ross M, et al. Meta-analysis of sentinel lymph node biopsy following preoperative chemotherapy in patients with operable breast cancer. ASCO Annual Meeting, 2004, New Orleans, LA abstract 561.

14 Huston TL, Osborne MP. Evaluating and staging the patient with breast cancer. In: Ross D, editor. Breast Cancer. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005:309-318.

15 Schirrmeister H. Detection of bone metastases in breast cancer by positron emission tomography. PET Clin. 2006;1(1):25-32.

16 Chom Y, Chan K, Lam W, et al. Comparison of whole body MRI and radioisotope bone scintigram for skeletal metastases detection. Chin Med J (Eng1). 1997;110(6):485-489.

17 Cook GJ, Houston S, Rubens R, et al. Detection of bone metastases in breast cancer by 18 FDG PET: differing metabolic activity in osteoblastic and osteolytic lesions. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(10):375-379.

18 Ohta M, Tokuda Y, Suzuki Y, et al. Whole body PET for the evaluation of bony metastases in patients with breast cancer: comparison with 99 m Tc-MDP bone scintigraphy. Nucl Med Commun. 2001;22(8):875-879.

19 Yang SN, Liang JA, Lin FJ, et al. Comparing whole body 18F-2 deoxyglucose positron emission tomography and technetium-99 m methylene diphosphonate bone scan to detect bone metastases in patients with breast cancer. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2002;128(6):325-328.

20 Uematsu T, Yuen S, Yukisawa S, et al. Comparison of FDG PET and SPECT for detection of bone metastases in breast cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184(4):1266-1273.

21 Ciatto S, Pacini P, Azzini V, et al. Preoperative staging of primary breast cancer: a multicentric study. Cancer. 1988;61(5):1038-1040.

22 Dose J, Bleckmann C, Bachmann S, et al. Comparison of fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography and “conventional diagnostic procedures” for the detection of distant metastases in breast cancer patients. Nucl Med Commun. 2002;23(9):857-864.

23 Reinig JW, Dwyer AJ, Miller DL, et al. Liver metastasis detection: comparative sensitivities of MR imaging and CT scanning. Radiology. 1987;162:43-47.

24 Eberhardt SC, Choi PH, Bach AM, et al. Utility of sonography for small hepatic lesions found on computed tomography in patients with cancer. J Ultrasound Med. 2003;22(4):335-343.

CASE 1 LABC (large tumor size)

A 45-year-old woman was noted on routine physical examination by her physician to have an abnormal left breast examination. Although the patient had not noted any discrete masses, an area of induration and irregularity was palpated in the left upper breast, extending from upper inner to upper outer quadrant.

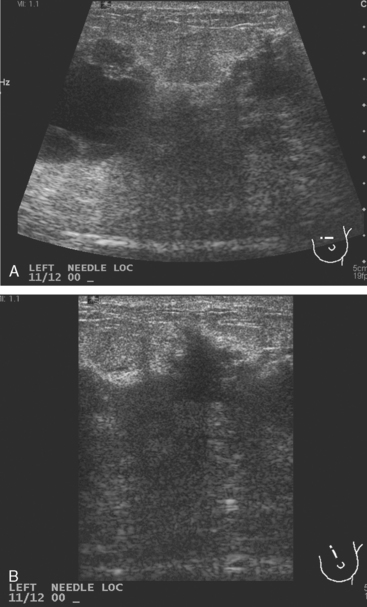

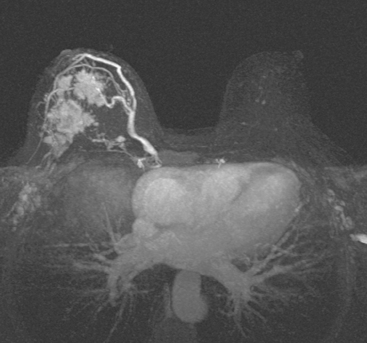

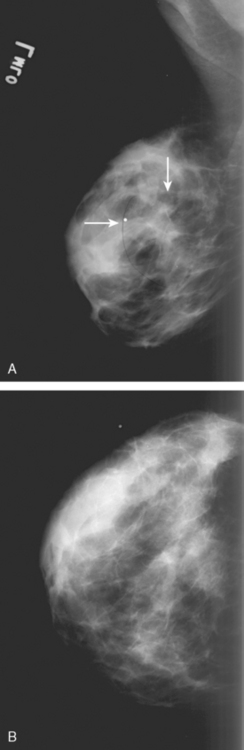

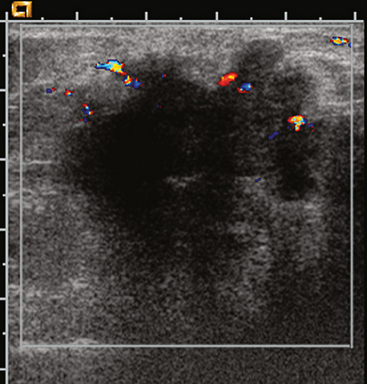

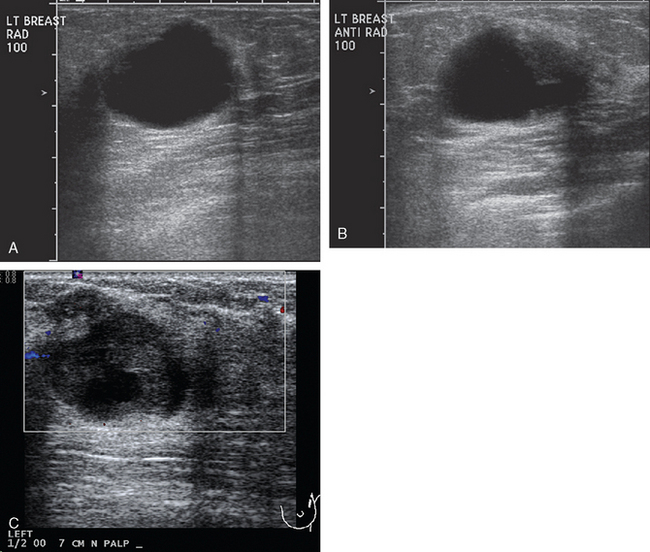

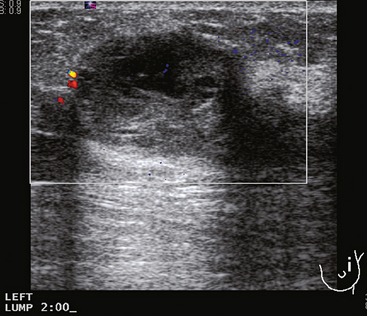

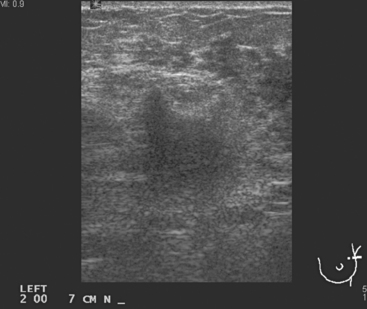

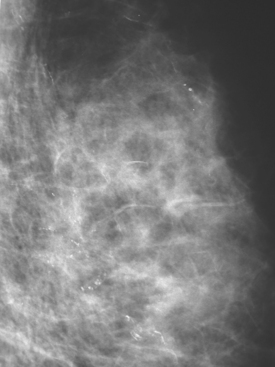

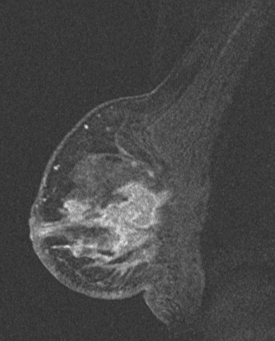

Breast imaging evaluation showed extremely dense breast parenchyma. New clustered microcalcifications were identified in the upper inner quadrant (UIQ). Sonography showed irregular, hypoechoic parenchymal echotexture in the left upper breast at 11 to 12 o’clock with cysts and shadowing (Figure 1), and the region of the microcalcifications was visualized as well. Ultrasound-guided biopsy confirmed infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC) with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS).

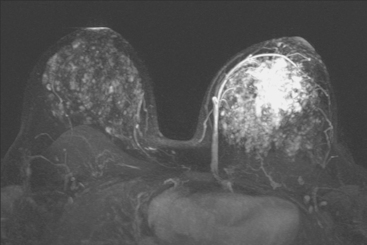

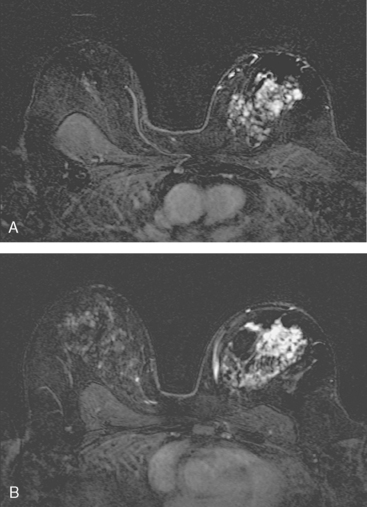

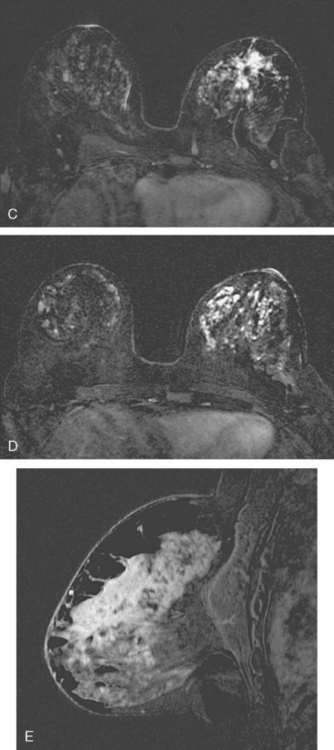

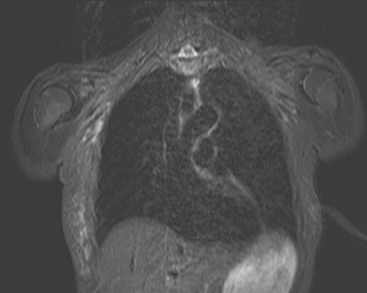

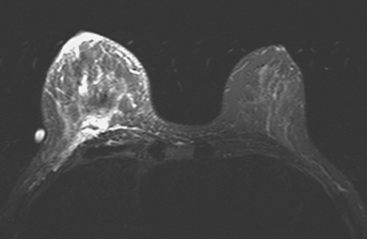

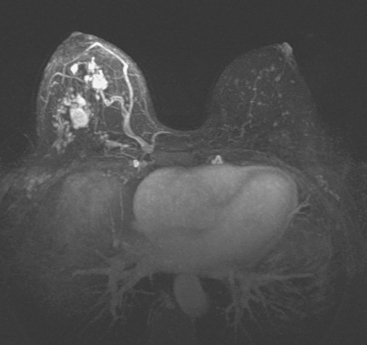

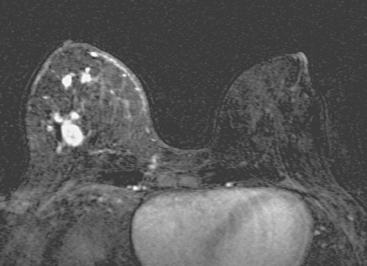

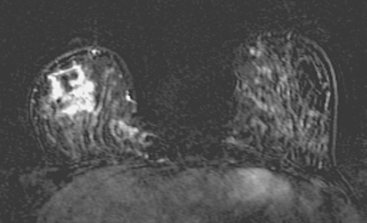

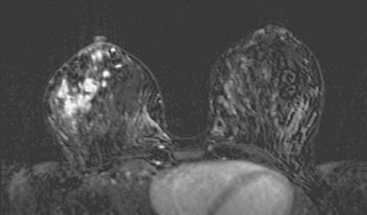

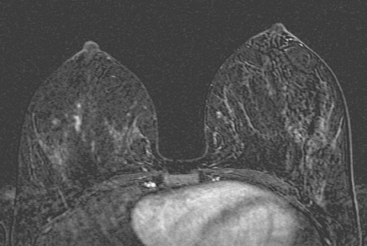

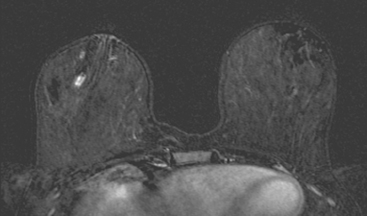

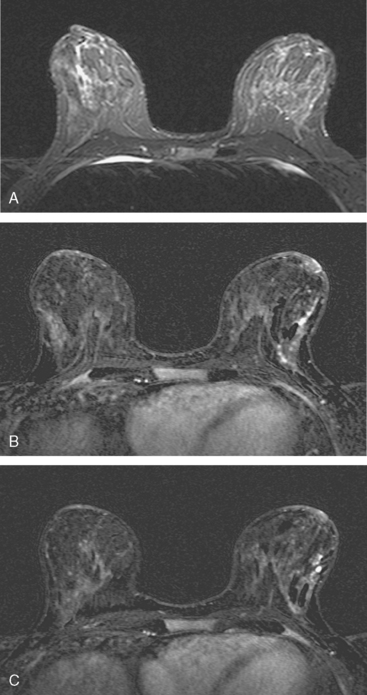

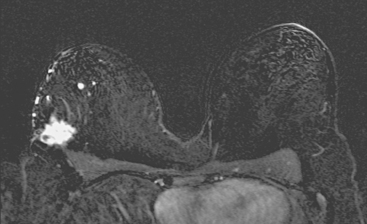

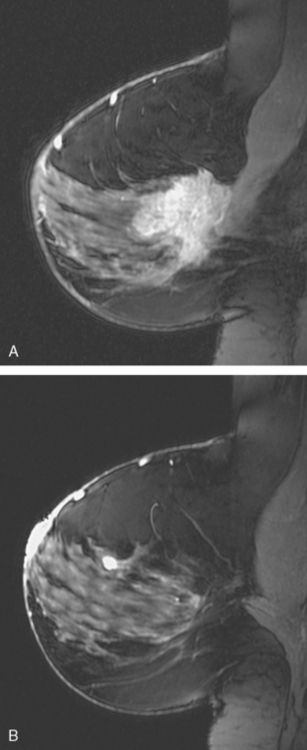

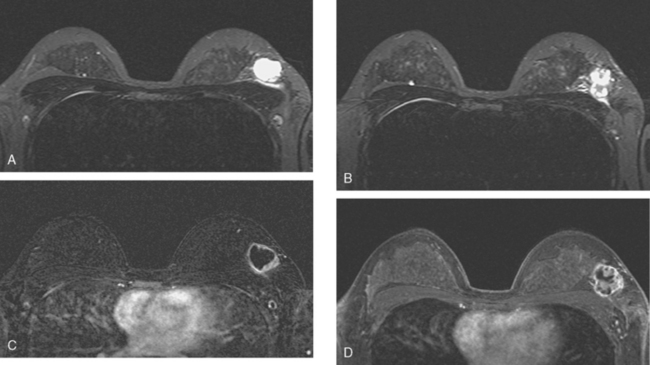

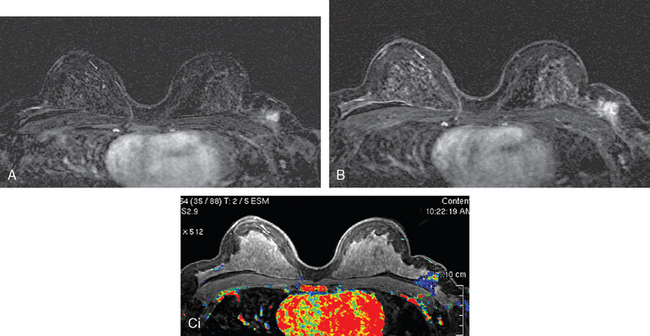

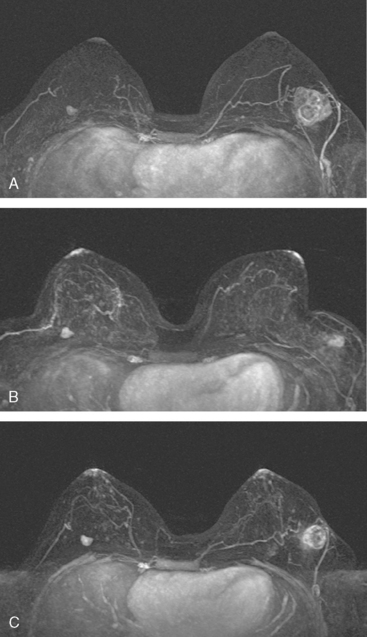

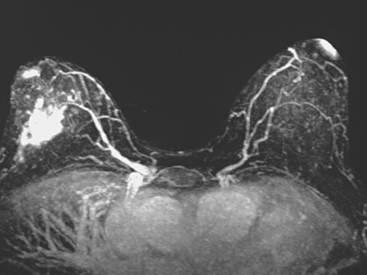

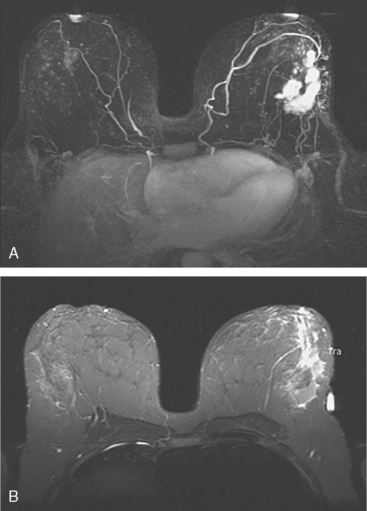

Breast MRI showed striking asymmetry between the two sides, with findings of a very large, diffusely infiltrating cancer on the left (Figures 2 and 3). The intensely enhancing process, centered at 12 o’clock but spanning 11 to 2 o’clock, showed architectural distortion, with additional extensive clumped enhancement diffusely involving the medial breast. By MRI, the abnormality measured at least 6 cm and involved at least two quadrants extensively, indicating that the patient was not a conservation candidate.

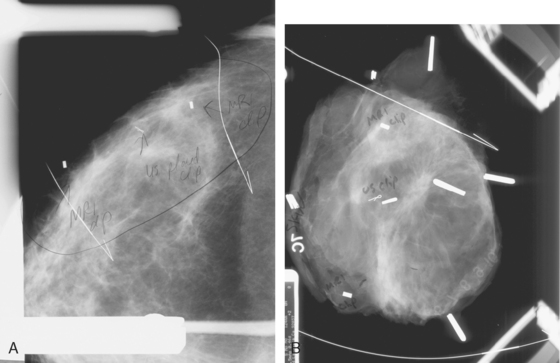

The mastectomy specimen showed an 8-cm IDC of the central breast extending into the upper inner and lower inner quadrants, with a high-grade DCIS component involving 50% of the lesion (extensive intraductal component). Multifocal satellite tumor nodules were noted within the large tumor. Extensive angiolymphatic involvement was seen, and four sentinel lymph nodes showed metastatic carcinoma (Figure 4). Completion axillary dissection showed no additional axillary disease, for a total of 4 of 20 lymph nodes positive for metastatic disease. The deep mastectomy margin was negative.

The patient underwent imaging staging postoperatively, with bone scan, CT, and positron emission tomography (PET) (Figures 5 and 6), which showed only postsurgical changes of the axilla and chest wall and no evidence of distant metastatic disease. Final stage was stage IIIA, with T3N1M0 disease, and the tumor was estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive.

TEACHING POINTS

Accurate and timely communication between specialties is a critical part of the care of the newly diagnosed breast cancer patient, as this case illustrates. Evaluations up to the point of the breast MRI had not shown clear evidence that the patient was not a lumpectomy candidate, and so the treatment planning was proceeding with this expectation. One examiner’s concern that there might be a discrepancy between the imaging findings and the clinical examination led to performance of breast MRI, which confirmed a very large, locally advanced tumor. Unfortunately, this was ordered at the last minute and without the knowledge of the surgeon. Fortunately, the radiologist charged with performing the needle localization on the day of surgery was able to rectify the situation, which was precipitously, but satisfactorily, resolved in favor of the patient undergoing mastectomy.

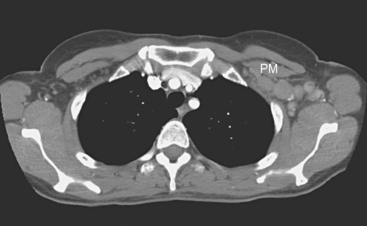

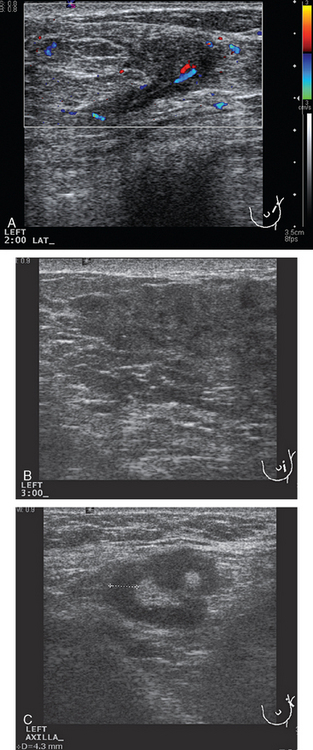

CASE 2 LABC with axillary and internal mammary involvement; staging with whole-body PET and PEM

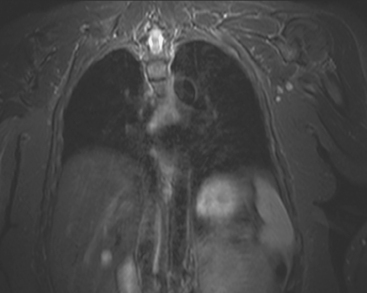

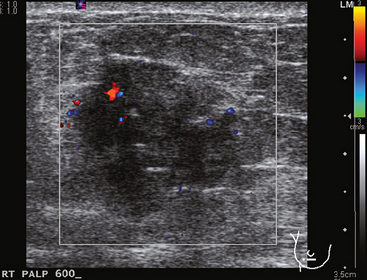

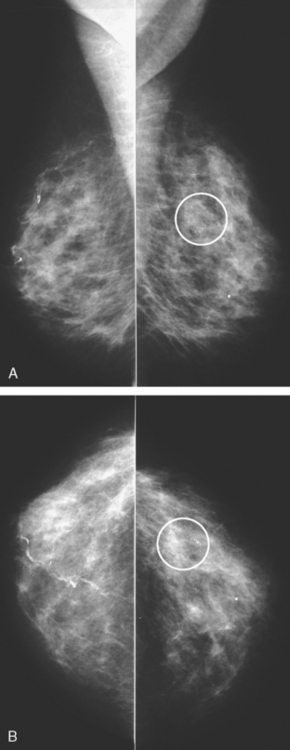

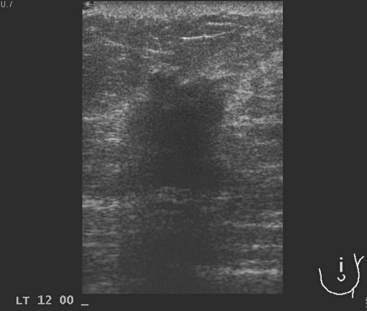

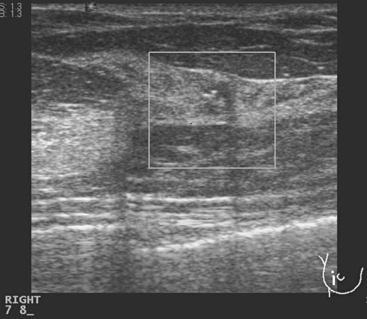

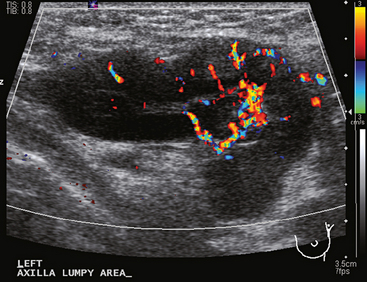

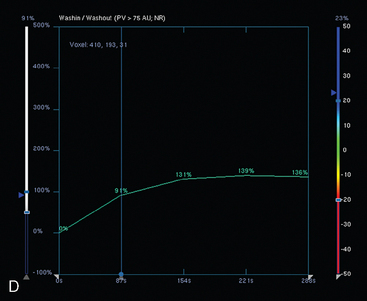

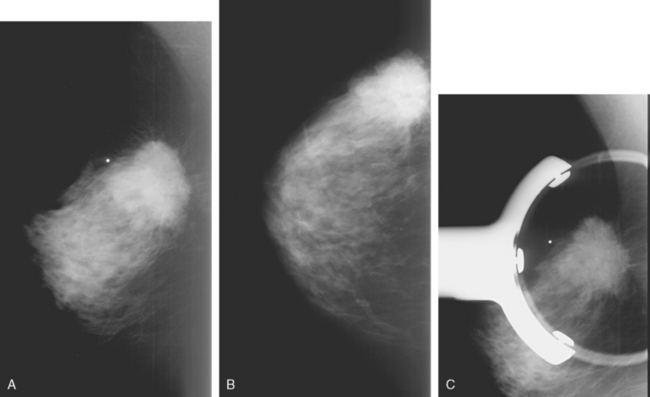

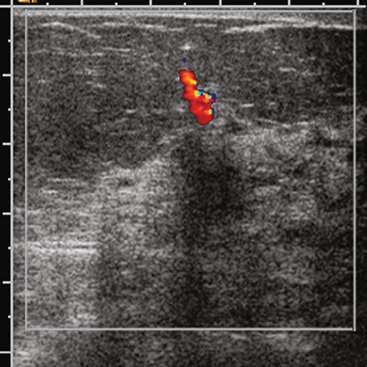

A 77-year-old woman was noted on routine physical examination by her primary care physician to have a palpable 3-cm mass on the right at 6 o’clock. Breast imaging evaluations confirmed this mass, which was best seen on ultrasound as a 3.2-cm mass with lobular and irregular margins (Figure 1). On ultrasound, a second suspicious mass, which was not seen mammographically, was noted medial to the dominant mass, at 4 o’clock (Figures 2 and 3). This was a bilobed, hypoechoic mass. A highly suspicious axillary lymph node was also found, measuring 2.3 cm, with complete effacement of the fatty hilus (Figure 4).

These three abnormalities were biopsied with ultrasound guidance. Both the 4- and 6-o’clock breast masses were poorly differentiated infiltrating ductal carcinomas (IDC), estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor negative, HER-2/neu negative, grade 8/9. The axillary lymph node fine-needle aspiration showed adenocarcinoma, consistent with metastatic breast carcinoma.

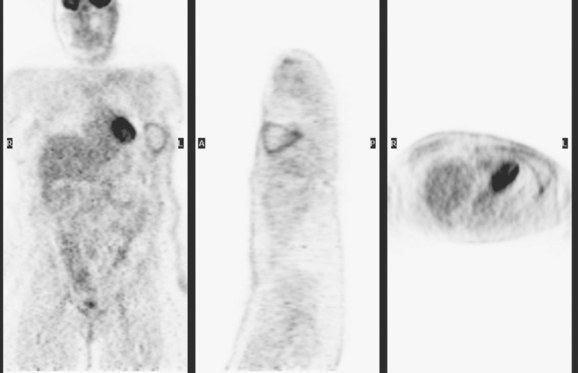

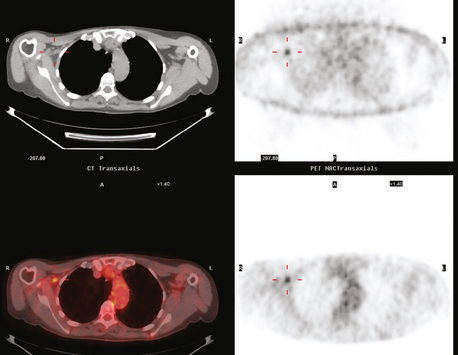

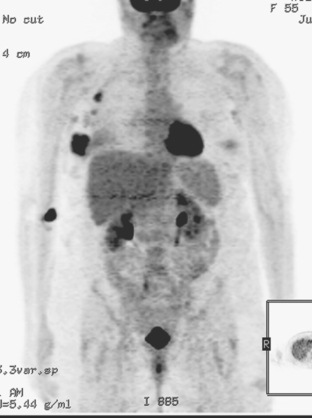

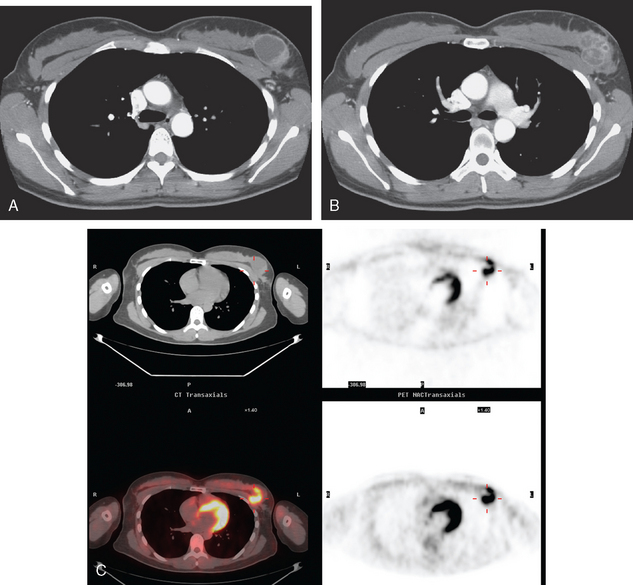

Bone scan suggested an L1 compression fracture as the etiology of back pain (Figure 5). A band of modest increased metabolic activity was seen at the superior end plate of L1 on PET, and CT showed superior end-plate invagination, confirming the bone scan impression of a compression fracture (Figure 6). Three right lower inner quadrant FDG-avid breast masses were seen on whole-body PET/CT, with a small additional FDG-avid nodule seen between the two known IDC masses at 4 and 6 o’clock. The known involved right axillary lymph node was intensely hypermetabolic and was accompanied by several smaller additional metabolically active axillary lymph nodes. Activity was also seen in two internal mammary lymph nodes, which on CT measured 8 mm (Figures 7 and 8).

A PEM study was also obtained in this patient after completion of PET/CT, using the same FDG dose. The proven multifocality of her tumor would ordinarily have been an indication for breast MRI, but the patient could not readily undergo breast MRI because of her pacemaker. The dominant mass on the right at 6 o’clock was seen with exquisite detail on PEM, with intense heterogeneous uptake of FDG (Figure 9). The 4-o’clock mass was not seen on either view. This result was anticipated because of its far posterior position on the chest wall on CT. The small, intermediately positioned satellite tumor mass was visualized on the mediolateral oblique (MLO) projection, which shows more posterior breast tissue. The PEM also permitted more thorough screening of the left breast.

CASE 3 LABC with nipple skin involvement

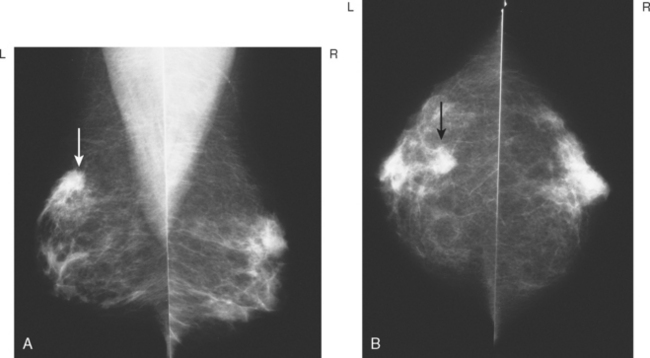

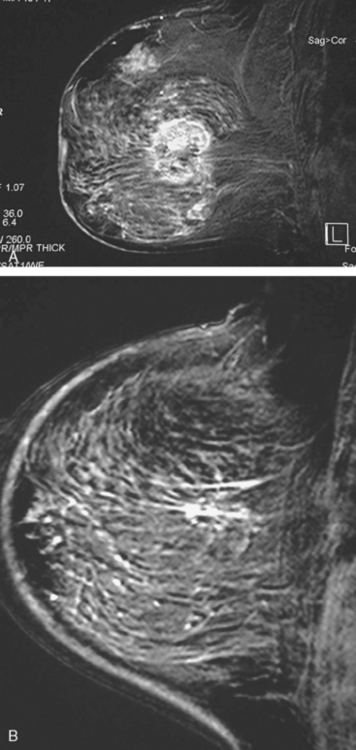

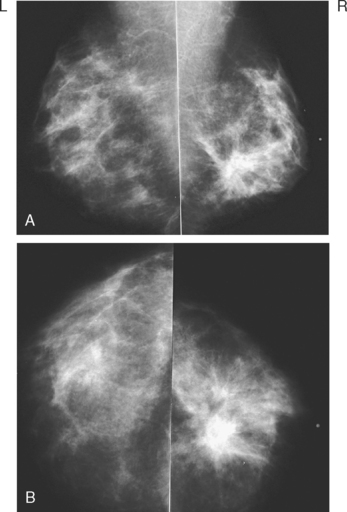

A 56-year-old woman noted new right nipple inversion 4 months before presenting for breast imaging evaluation for a newly developed right palpable axillary lump. Mammography and ultrasound showed a dominant 12-o’clock mass with nipple retraction and localized skin thickening, as well as axillary lymphadenopathy (Figures 1, 2, and 3). Ultrasound-guided biopsy of the dominant mass confirmed invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), and ultrasound-guided axillary node fine-needle aspiration confirmed metastatic disease. Periareolar dusky erythema was noted, and skin punch biopsy was performed, which was negative. Local staging was completed with breast MRI (Figures 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8).

Systemic staging with positron emission tomography (PET)/CT showed fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) avidity of the known right breast cancer and axillary lymphadenopathy, but no additional disease. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was given, consisting of four cycles each of doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) (AC) and paclitaxel (Taxol). The nipple inversion resolved, and there was marked clinical regression of the dominant mass. Modified radical mastectomy and axillary dissection were performed. A 4.5-cm residual lesion of admixed IDC and normal breast tissue remained. Margins were negative, and 5 of 13 lymph nodes showed metastatic tumor. Chest wall, supraclavicular, and posterior axillary boost radiation therapy were given, and the patient was placed on anastrozole (Arimidex).

CASE 4 Natural history of untreated inflammatory breast cancer

A 57-year-old woman noted her right breast to be enlarged and heavier feeling. Mammography showed concerning right upper outer quadrant (UOQ) microcalcifications (Figures 1 and 2). Right breast sonogram showed periareolar skin thickening (Figure 3) and an UOQ 1.5-cm shadowing hypoechoic mass with irregular margins (Figure 4), as well as hypoechoic, rounded, axillary lymph nodes (Figures 5 and 6). Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of the UOQ mass confirmed infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC), estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor negative, HER-2/neu negative. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of an axillary lymph node confirmed metastatic carcinoma, consistent with breast primary origin. Two skin punch biopsies were performed because of clinical suspicion of inflammatory carcinoma: both were negative. Skin biopsies were subsequently repeated because of persistent high suspicion of inflammatory cancer, and confirmed intralymphatic carcinoma.

FIGURE 2 Lateral magnification view of the right upper breast shows concerning new microcalcifications.

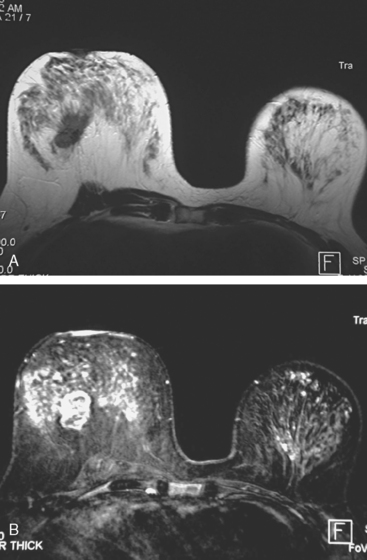

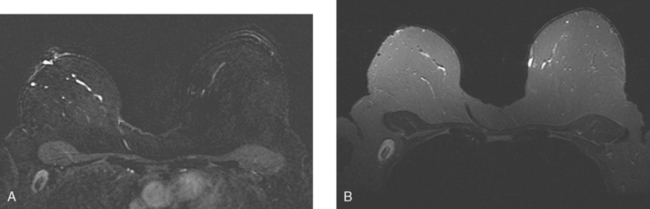

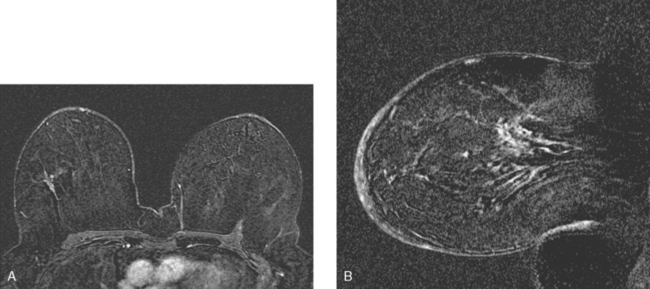

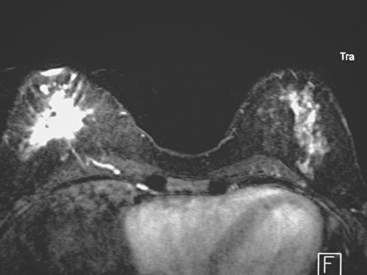

Breast MRI showed multiple intensely enhancing right breast masses, as well as enhancement of the skin (Figures 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11). Systemic staging consisted of positron emission tomography (PET)/CT and enhanced body CT scans. Hypermetabolism was identified in the right breast and axillary lymph nodes, but no evidence of distant metastatic disease was found (Figures 12, 13, 14, 15).

The patient initially declined all conventional therapies and opted against medical advice for a trial of an alternative soy product. After 3 months, she underwent repeat breast MRI and PET/CT to assess her response. The breast MRI showed growth of the multiple breast masses to near confluency (Figures 16 and 17). PET/CT showed progression in the breast and axilla, but no distant metastases. Four cycles of doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) (AC) neoadjuvant chemotherapy were given, after which the patient underwent a right modified radical mastectomy and axillary lymph node dissection. The mastectomy specimen showed a 5.5-cm IDC with high-grade comedo DCIS and dermal intralymphatic carcinoma. Angiolymphatic invasion was extensive, both peritumoral and distant. The margins showed intralymphatic carcinoma at skin margins. Fourteen out of 14 lymph nodes showed tumor, with extranodal soft tissue extension and involvement of perinodal lymphatic spaces.

FIGURE 17 Sagittal, subtracted, enhanced right breast MRI from the same study as Figure 16, showing how confluent the diffuse process has become. Skin thickening and enhancement is most pronounced inferiorly.

Gunhan-Bilgen I, Ustun EE, Memis A. Inflammatory breast carcinoma: mammographic, ultrasonographic, clinical, and pathologic findings in 142 cases. Radiology. 2002;223(3):829-838.

Kushwaha AC, Whitman GJ, Stelling CB, et al. Primary inflammatory carcinoma of the breast: retrospective review of the mammographic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2000;174:535-538.

Whitman GJ, Kushwaha AC, Christofanilli M, et al. Inflammatory breast cancer: current imaging perspectives. Semin Breast Dis. 2001;4(3):122-131.

CASE 5 LABC with secondary inflammation (secondary inflammatory breast cancer)

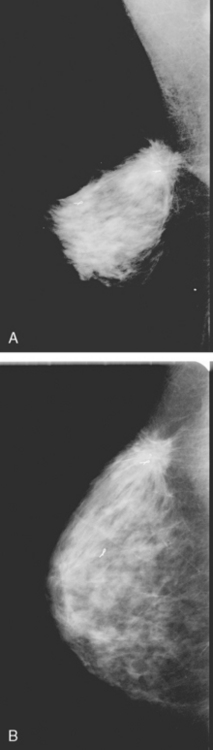

A 56-year-old woman was noted to have a highly suspicious, spiculated, 1- to 1.5-cm mass in the left breast on screening mammography, for which biopsy was recommended (Figure 1). The patient decided not to undergo a biopsy, on the advice of her chiropractor.

Two and a half years later, the patient noted a change in the left breast, with nipple hardening and aching. The patient also noted an imprint on her lower breast from her underwire bra. Mammography showed an ill-defined spiculated mass at 12 o’clock, which had grown (Figure 2). She was clinically evaluated by a surgeon, who noted skin changes of edema and peau d’orange. A discrete mass was difficult to palpate, being nearly behind the nipple, with generalized thickening and firmness noted. A palpation-guided biopsy was performed, as well as a skin punch biopsy. Infiltrating ductal carcinoma, estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive, was identified from both biopsies, with tumor in vascular and lymphatic channels in the skin biopsy.

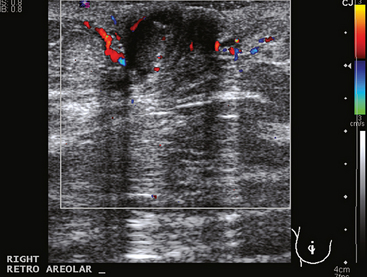

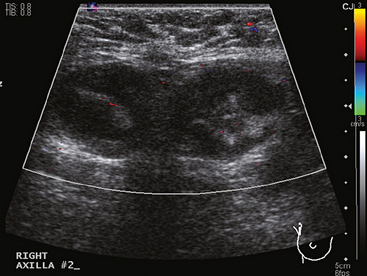

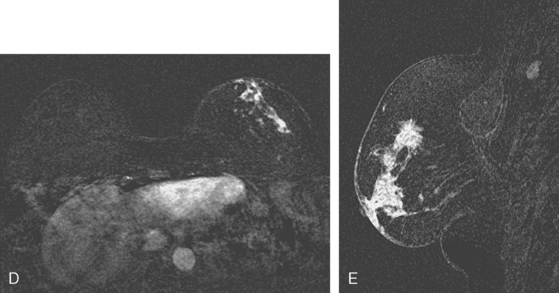

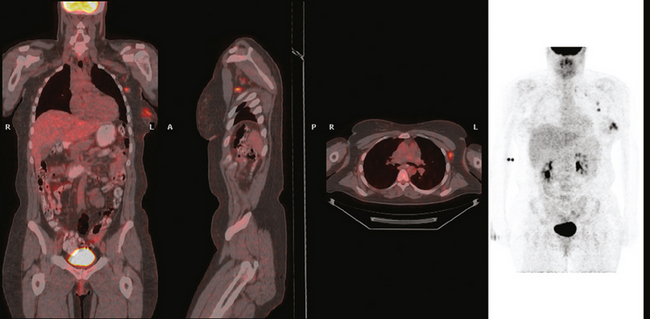

Staging evaluations were obtained, including bilateral breast ultrasound (Figures 3 and 4); breast MRI (Figure 5); positron emission tomography (PET)/CT (Figure 6); chest, abdomen, and pelvic enhanced CT scans (Figure 7); and bone scan. These studies showed a very extensive left breast cancer, with involvement of the nipple and skin, with evidence on multiple studies of axillary nodal involvement, but no evidence of distant metastatic disease. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was recommended. The patient decided to pursue alternative and nutritional therapies and declined all conventional therapy. She did agree to periodic laboratory analysis and clinical examination. One year after diagnosis, although the patient’s tumor markers continued to rise and there was clear local progression clinically (ulceration of the left nipple and nodularity of the skin), the patient continued to decline conventional therapy.

TEACHING POINTS

Axillary nodal involvement was never established histologically in this patient, but the imaging evidence of multiple node involvement is compelling. In particular, the PET is strong presumptive evidence of axillary disease, with five fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-avid lymph nodes readily visualized. In a large, prospective, multicenter study of 360 women with newly diagnosed invasive breast cancer, two or more PET-positive intense axillary foci of uptake were highly predictive of axillary metastases. This would be sufficient evidence of involvement to proceed directly to axillary dissection without sentinel lymph node sampling, if the patient were undergoing surgery. In a patient such as this, who ordinarily would be treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, FDG PET is a reliable indicator of the extent of disease.

Avril N, Adler LP. F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography imaging for primary breast cancer and loco-regional staging. PET Clinics: Breast Cancer. 2006;1(1):1-13.

Wahl RL, Siegel BA, Coleman E, et al. Prospective multicenter study of axillary nodal staging by positron emission tomography in breast cancer: a report of the staging breast cancer with PET study group. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:277-285.

CASE 6 PABC, treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy with complete pathologic response

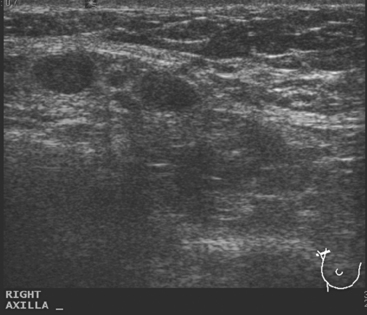

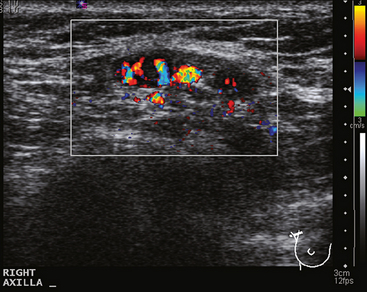

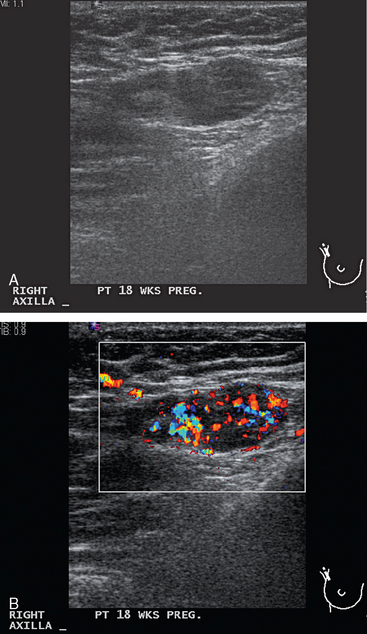

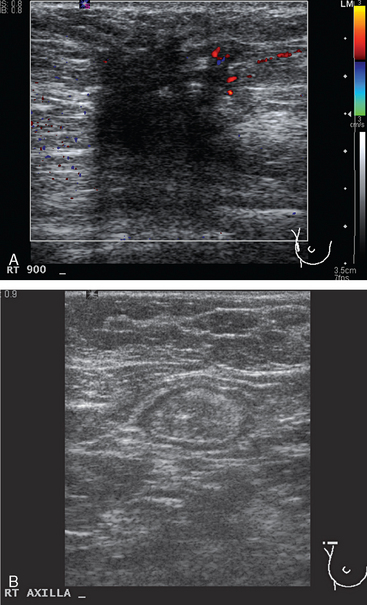

A 33-year-old pregnant patient noted a palpable right breast lump at about 18 weeks of gestation. This was confirmed by her obstetrician, who performed a fine-needle aspiration. No diagnosis or fluid was obtained. Ultrasound identified a suspicious 2.2-cm mass, as well as an abnormal and enlarged axillary lymph node (Figures 1 and 2). Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy of the breast mass revealed high-grade infiltrating ductal carcinoma, and fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the axillary lymph node showed metastatic carcinoma, consistent with breast primary.

On palpation, the mass was large, in the lower outer quadrant, estimated at 6 to 8 cm in size, and thought to be too large to attempt breast conservation. A 2-cm axillary lymph node was also palpable and mobile. The patient was interested in breast preservation and in continuing with her pregnancy, and so neoadjuvant chemotherapy was performed with four cycles of doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) (AC).

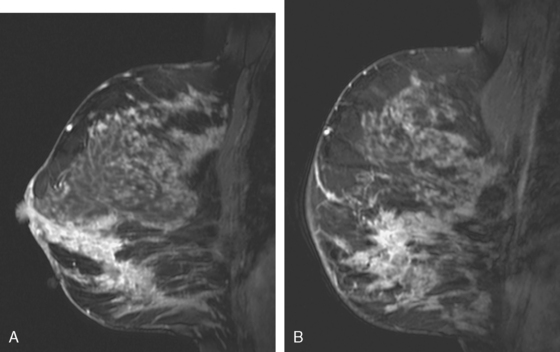

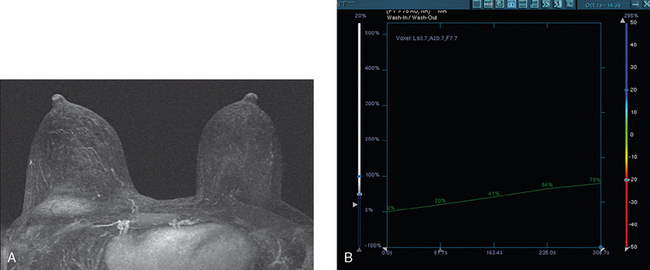

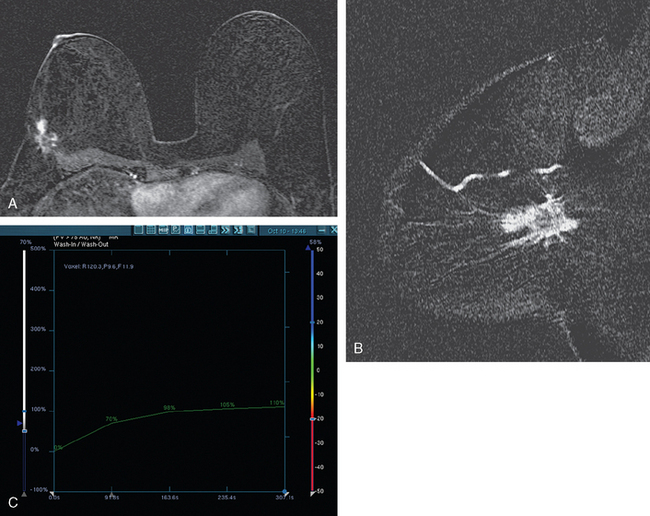

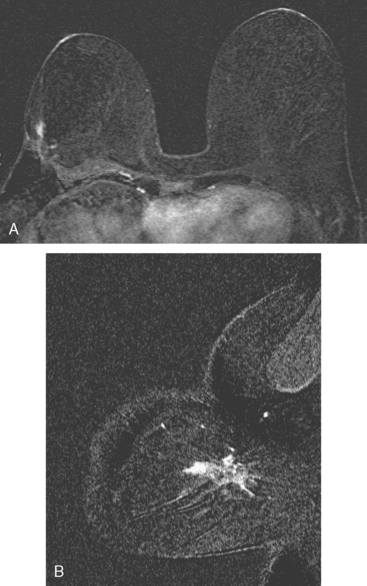

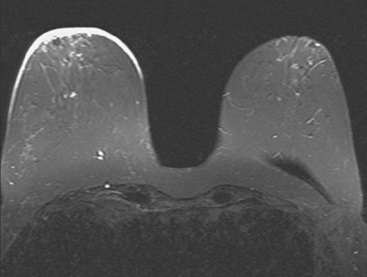

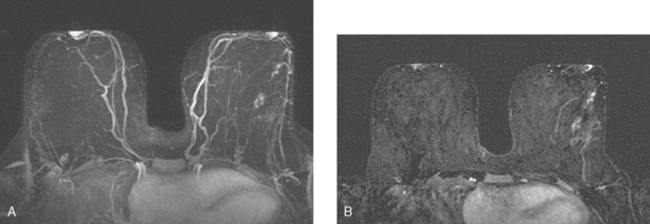

Breast MRI was obtained to assess the extent of disease, given the discrepancy between physical examination and ultrasound. It showed a large, dominant, irregularly marginated mass occupying most of the lower outer quadrant (LOQ) and measuring 8.1 cm in maximal dimension (Figures 3, 4, 5, 6, and 7). Clinical stage was stage III, T3N1, estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor low positive, HER-2/neu positive.

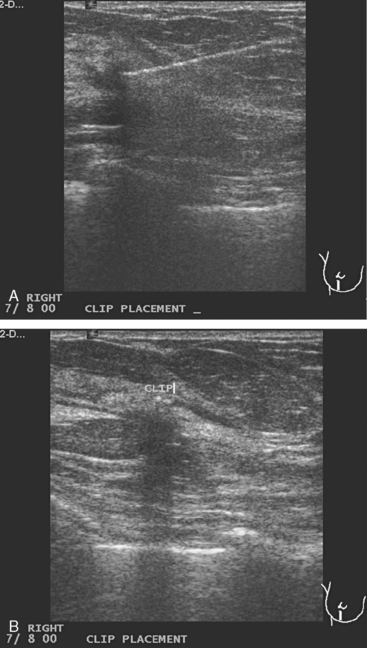

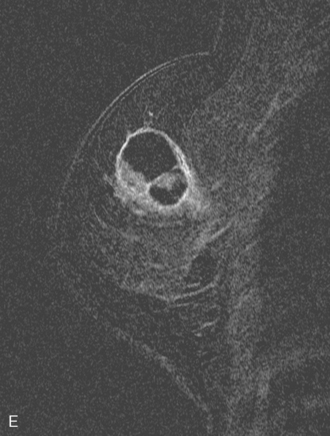

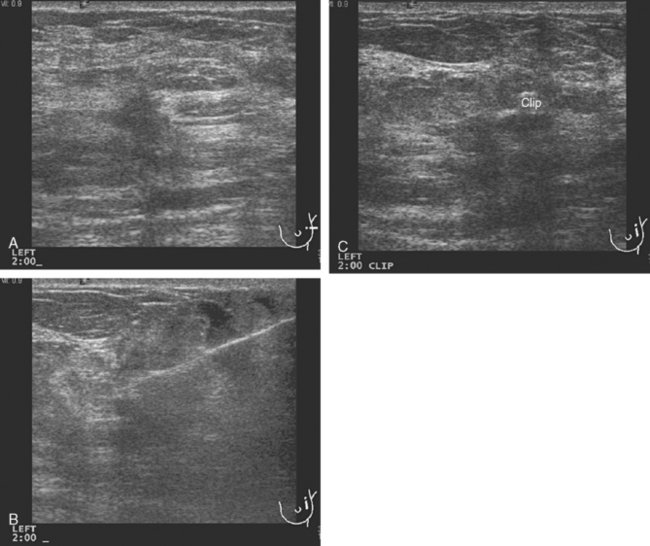

Her chemotherapy was resumed after delivery, with weekly Taxol and Herceptin for 12 weeks, with Herceptin planned weekly for 40 additional weeks (1 year total). Mid-chemotherapy restaging studies were obtained, showing a smaller ultrasound residual mass, now 1.2 cm, and resolution of the abnormal axillary findings (Figure 8). Given the marked imaging regression of the tumor, the patient underwent ultrasound-guided clip placement into the residual for future localization (Figure 9). Repeat breast MRI showed marked regression of the mass, reduced to a linear residual (Figure 10).

Staging studies were repeated 2 months later, after completion of Taxol therapy, and showed further regression, with only minimal residuals on both ultrasound and MRI (Figures 11 and 12). The patient was treated surgically with a partial mastectomy, which showed no invasive carcinoma and negative margins. A limited axillary dissection removing six lymph nodes was performed, and there was no evidence of metastatic tumor in the sampled nodes. Radiation therapy was subsequently administered to the breast and supraclavicular region.

TEACHING POINTS

This case well illustrates the typical features of breast cancers diagnosed during pregnancy, which tend to be large and node-positive and may be inoperable. Pregnancy-associated breast cancer (PABC) is generally defined as breast cancer diagnosed during pregnancy or within a year of delivery. PABC tends to be advanced at diagnosis, with contributions from physician and patient-related delays in diagnosis. The difficulty of physical examination in pregnancy and lactation-engorged breasts is thought to contribute to delayed diagnosis.

Ultrasound is an excellent first imaging choice in assessing a palpable mass in a pregnant patient. If ultrasound did not identify a mass or satisfactory explanation for a palpable lump, the imaging evaluation could safely be extended to include mammography, based on an estimated fetal dose of 500 μGy from two-view film screen mammography with abdominal shielding.

In formulating a treatment plan for a pregnant patient with breast cancer, the usual approach is to treat the cancer while allowing the pregnancy to proceed. Both surgery and chemotherapy can be safely performed during pregnancy, whereas radiation is preferentially given after delivery. In this case, the patient was initially considered for mastectomy while pregnant, but her excellent response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy during pregnancy enabled successful lumpectomy, performed after induced delivery.

CASE 7 Postpartum LABC, with multiple axillary nodes involved; excellent response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy

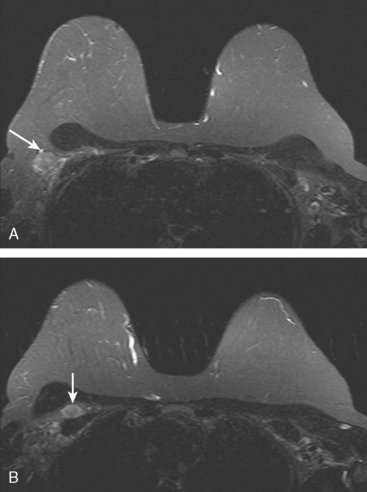

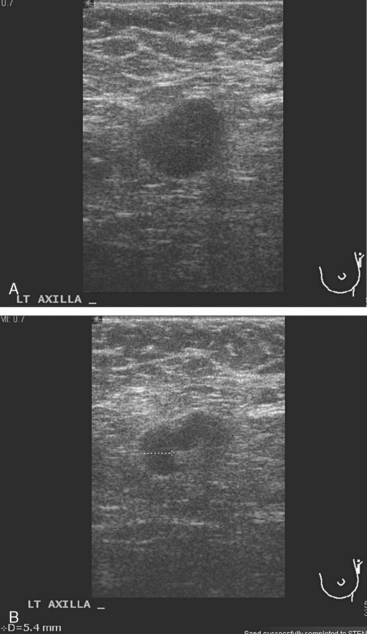

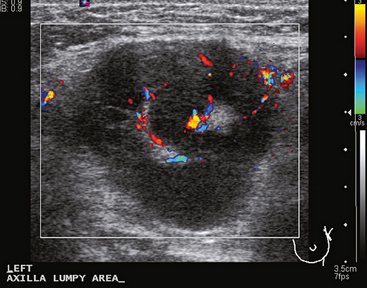

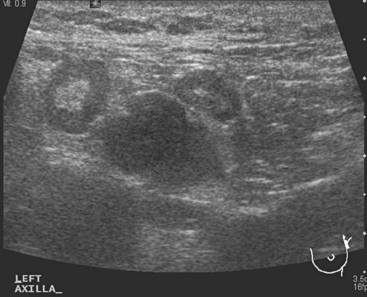

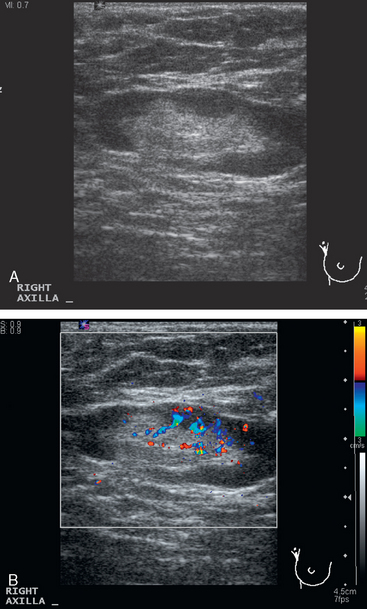

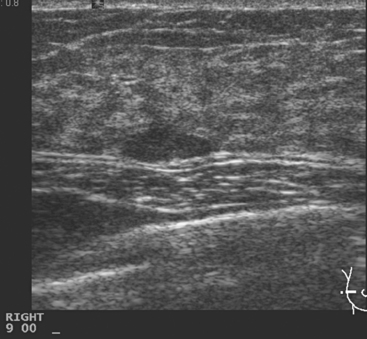

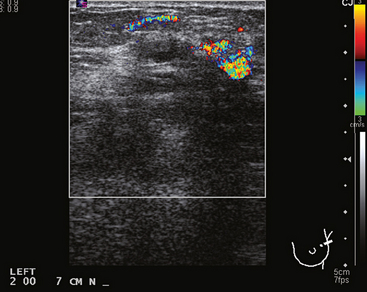

A 41-year-old woman, 4 months postpartum and tapering breast-feeding, noted a left axillary lump. She also noted left breast tenderness and swelling. A massively enlarged and vascular axillary lymph node was found on ultrasound, which also showed a region in the left upper outer quadrant (UOQ) of parenchymal hypoechogenicity (Figures 1, 2, 3, and 4). Core needle biopsy with ultrasound guidance of the left UOQ showed infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC), estrogen receptor negative, progesterone receptor weakly positive, HER-2/neu negative. Ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration (FNA) of the axillary lymph node showed a mixed population of lymphocytes, but no malignant cells. Clinically and morphologically, the axilla was suspected to be involved, despite the negative FNA. Physical examination of the breast noted a large area of nodularity and induration, estimated at 5 cm in size, but difficult to precisely define.

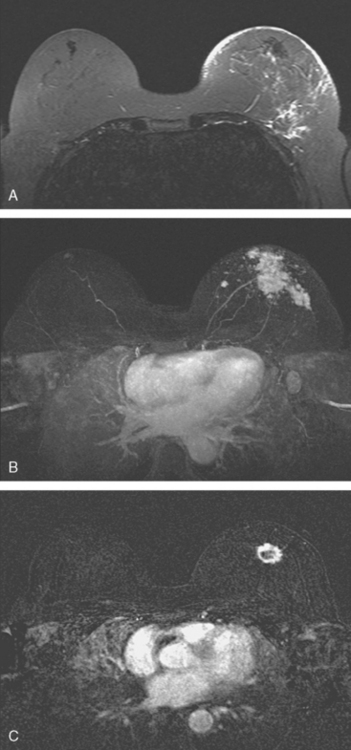

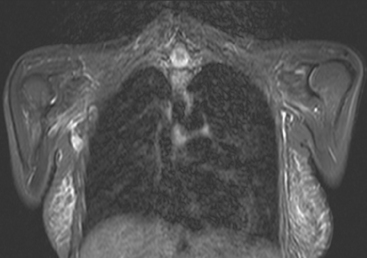

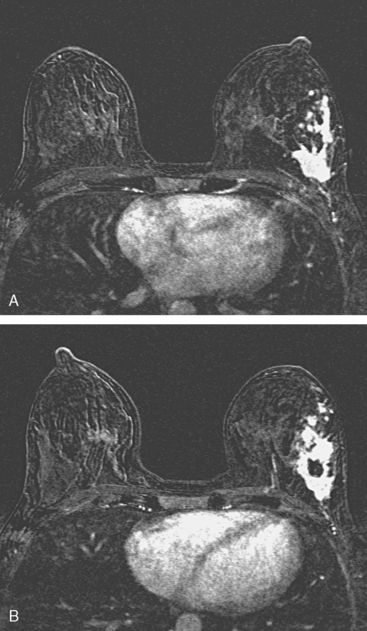

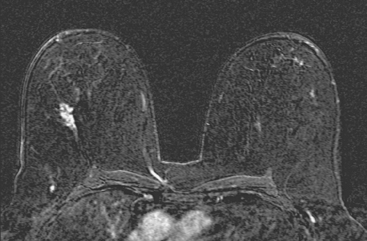

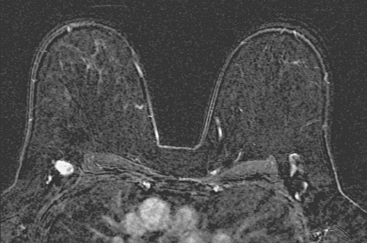

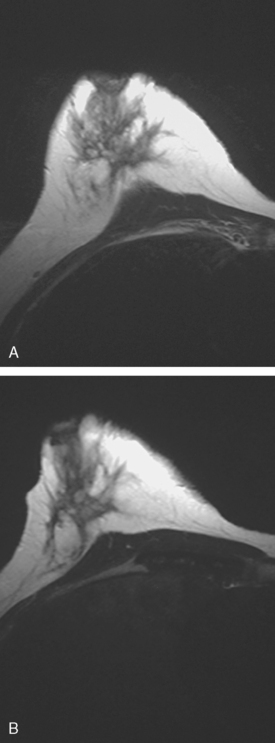

Breast MRI was obtained to better define the extent of the tumor (Figures 5 and 6). It showed a much larger area of involvement, spanning 8 cm in the left lateral breast. This consisted of multiple intensely enhancing masses, with clumped, linear, and ductal enhancement, oriented along a ductal ray.

FIGURE 6 Axial STIR images (A above B, at the same levels as Figure 5) show the lateral region of the left breast to be hypointense compared with the edematous, engorged appearance of the remainder of the breast. The appearance is in striking contrast to the right breast, which shows localized retroareolar ductal ectasia only. The lateral left breast skin is thickened and edematous, but showed no abnormal enhancement.

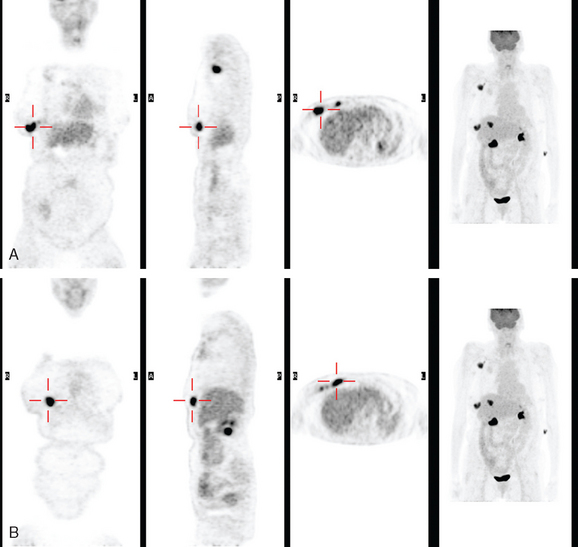

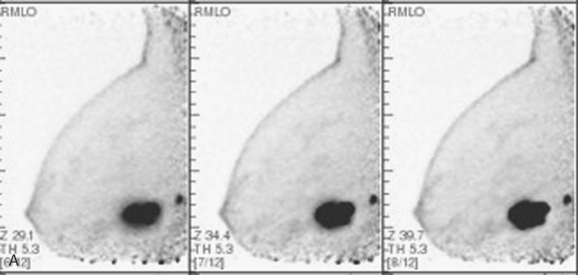

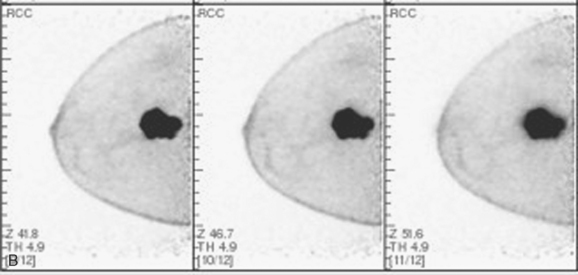

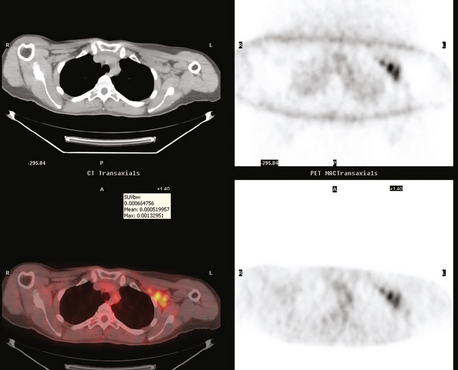

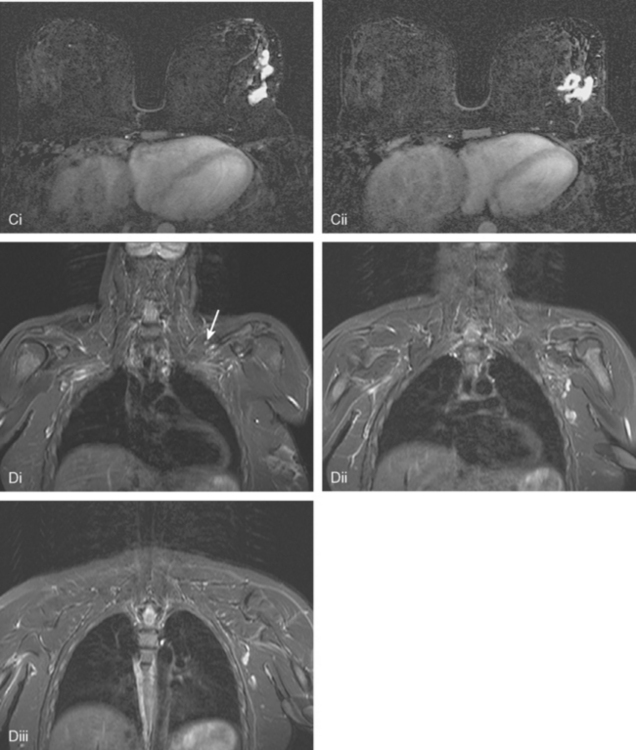

Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT and enhanced CT scans were obtained to systemically stage the patient. These showed intense multifocal hypermetabolism in the left lateral breast and in multiple left axillary enlarged lymph nodes (Figures 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11). No evidence of stage IV disease was seen.

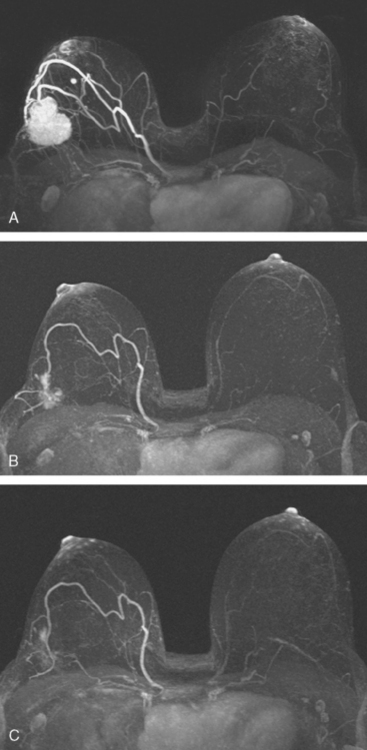

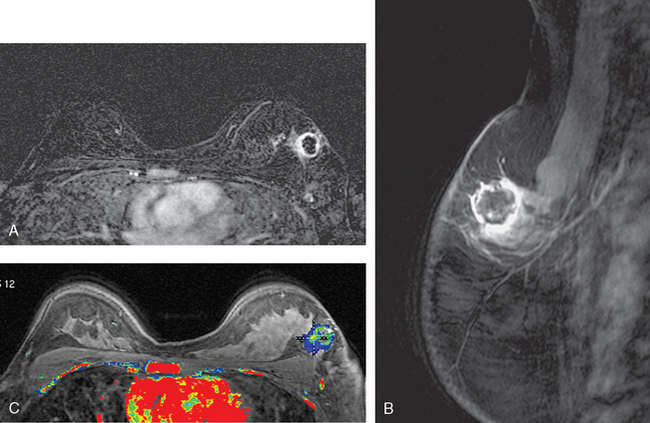

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy was recommended, owing to the large size of the tumor. Four cycles each of doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) (AC) and docetaxel (Taxotere) were given. Restaging with breast ultrasound and MRI (Figures 12, 13, and 14) and PET/CT was performed after four cycles of AC and again after 4 cycles of Taxotere (Figures 15 and 16). Restaging showed an excellent imaging response, with dramatic shrinkage and decreased enhancement of the tumor and axillary lymph nodes, and resolution of the PET uptake.

TEACHING POINTS

These axillary lymph nodes were so enlarged at presentation, a “plumbing problem” can be suspected to underlie the unusual pattern of edema and engorgement seen in the remainder of the left breast. The linear enhancing strands seen extending from the multifocal breast neoplasm toward the axilla suggest tumor-engorged lymphatics. The skin thickening and edema in the left lateral breast, best seen on STIR MRI and on chest CT, is not accompanied by enhancement, and so probably is part of the generalized engorgement and edema. Skin thickening with enhancement would be concerning for an inflammatory component.

CASE 8 IDC treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy with incomplete imaging response, but complete pathologic response

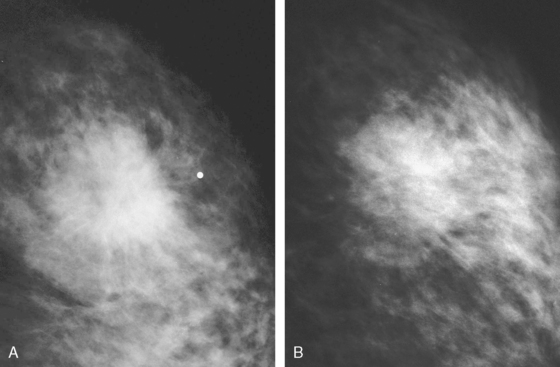

A 47-year-old woman presented with a growing palpable lump, noted initially a year before evaluation. Mammographic evaluation showed development since the prior year of a new upper outer quadrant (UOQ) right breast mass, which was 4 cm, spiculated, and associated with pleomorphic calcifications (Figure 1). Additional suspicious microcalcifications were seen medial and caudal to the dominant mass. Palpation-guided biopsy by a breast surgeon was suspicious with atypia, but not conclusive. Subsequently, ultrasound demonstrated a 2.9-cm mass (Figure 2), with highly suspicious features, and core needle biopsy with ultrasound guidance confirmed moderately differentiated infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC), estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive, HER-2/neu negative.

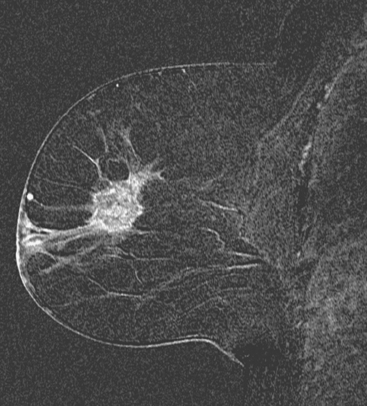

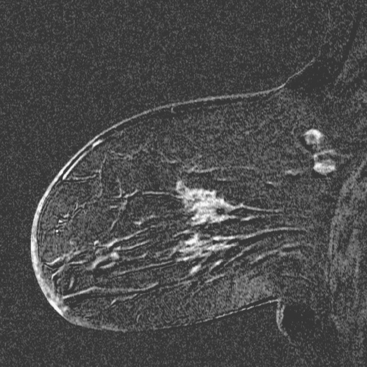

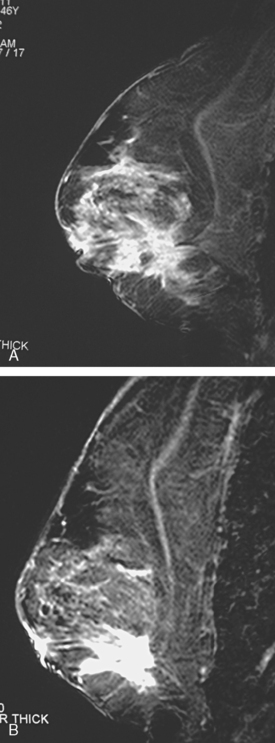

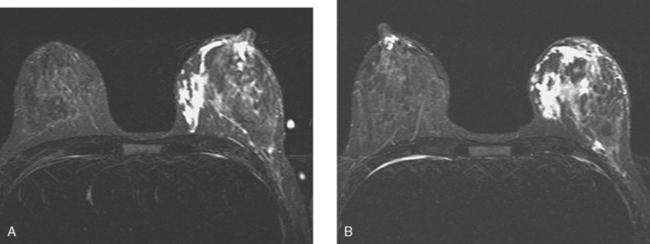

Breast MRI showed the mass to be larger than previously suspected, measuring 5 cm (Figures 3 and 4). The patient opted for neoadjuvant chemotherapy to downsize the tumor. The mass shrank in response, as assessed on follow-up mammograms and MRI (Figures 5 and 6). By MRI, the dominant mass declined in size from 5 cm pretreatment to 3 cm post-treatment, with an adjacent 1-cm mass inferomedially. Mammography showed a decline in size of the visible mass from 4 cm to 1.5 cm. However, sampling of the unchanged microcalcifications was now recommended, because of their location in the lower outer quadrant (LOQ), separate from the known IDC in the UOQ. Stereotactic biopsy confirmed the calcifications represented ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS), and with two quadrants involved, the patient was deemed unsuitable for breast conservation.

Additional therapy given included radiation therapy to the chest wall and supraclavicular fossa, and the patient was started on tamoxifen.

CASE 9 LABC, responsive to neoadjuvant chemotherapy; splenic activation on PET with G-CSF therapy

A 55-year-old woman saw a new primary care physician, who found on physical examination a large, firm, mobile, nontender right lateral breast mass. The patient attributed the lump to breast trauma in the same region 3 years before, and had noted no interval change since first identifying it.

Mammography confirmed a large spiculated new UOQ mass (Figure 1). Ultrasound confirmed a 6.6-cm mass at 9 o’clock with a separate 1.5-cm lesion at 12 o’clock and an enlarged and suspicious right axillary lymph node (Figures 2, 3, and 4). The surgeon noted right lateral breast skin indentation, with an easily palpable 6-cm mass with possible fixation. Palpation-guided core needle biopsy by the surgeon confirmed infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC), estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive. Breast MRI was requested to evaluate the question of fixation.

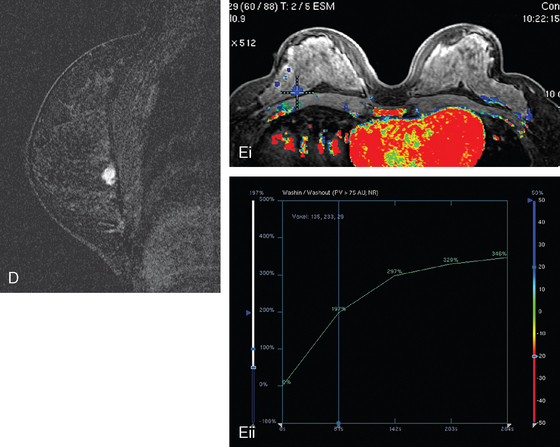

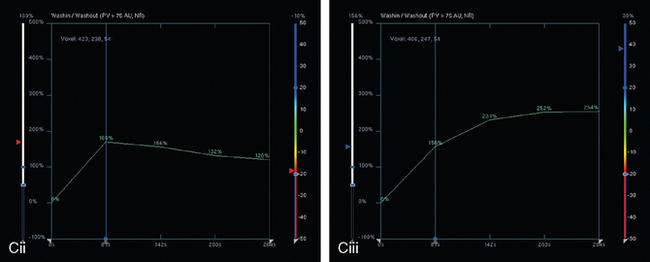

Breast MRI showed the dominant tumor to be a 5-cm, multilobulated, heterogeneously and rim-enhancing mass with washout. An additional, 7-mm enhancing mass at 12 o’clock, 3.5 cm away from the dominant IDC, showed washout as well and seemed to correlate with the separate abnormality seen on ultrasound (Figures 5, 6, 7, and 8).

Under ultrasound guidance, a clip was placed into the dominant 9-o’clock mass in anticipation of primary systemic chemotherapy. The satellite mass at 12 o’clock was marked with a clip at the time of biopsy, also confirming IDC. The largest axillary lymph node was sampled with fine-needle aspiration (FNA) technique, identifying malignant cells, consistent with metastatic adenocarcinoma.

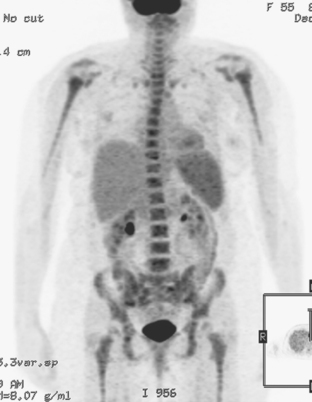

Systemic staging studies were undertaken, owing to the large tumor size and axillary involvement. Bone scan, positron emission tomography (PET)/CT, and enhanced body CT scans were obtained. The bone scan showed uptake of the radiopharmaceutical in the known right breast cancer, but no suspicious osseous findings (Figure 9). The PET scan showed intense hypermetabolism of the right lateral IDC, as well as of four right axillary level I and II lymph nodes, which were enlarged by CT (Figures 10 and 11). No distant metastases were seen on CT or PET. Because of the size of the tumor, neoadjuvant chemotherapy was recommended.

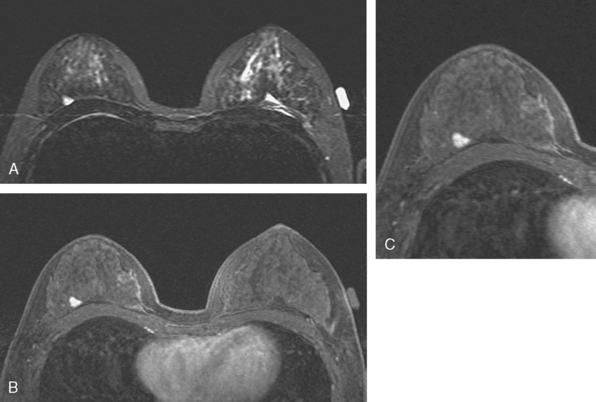

Four cycles of doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) (AC) were given, after which restaging studies of the breast were obtained. Clinically, there was a good response, with the palpable mass much less distinct and resolution of palpable adenopathy. Breast imaging with mammography, ultrasound, and MRI confirmed improvement, with decrease in size and enhancement of the dominant IDC and resolution on ultrasound and MRI of the 12-o’clock mass (Figures 12, 13, and 14).

After these restaging studies, additional chemotherapy was given with four cycles of docetaxel (Taxotere). Repeat breast imaging was obtained after completion of chemotherapy (Figures 15 and 16). The patient received granulocyte colonystimulating factor (G-CSF) with later cycles of chemotherapy after developing an infection and borderline white blood cell levels. Repeat PET scan after completion of chemotherapy showed complete resolution of the axillary nodal uptake, with nearly complete resolution of uptake in the breast. Marrow activation changes of bone were noted, and new increased activity was seen in the spleen as well (Figure 17).

TEACHING POINTS

This is a large, at least multifocal, node-positive, locally advanced breast cancer (LABC) treated initially with primary systemic (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy, with a good clinical and imaging response. The smaller IDC mass at 12 o’clock, never evident on mammography, completely resolved with chemotherapy by ultrasound and MRI. Fortunately, neoadjuvant chemotherapy had been anticipated, and a clip was placed to mark the site of the lesion at the time of biopsy. The center of the dominant 9-o’clock IDC was also marked. It is difficult to predict how complete a response any one patient or lesion will have to chemotherapy. To keep the patient’s choices open in case breast conservation therapy becomes a viable option, it is advisable to mark disease sites for subsequent localization in case a complete imaging response to chemotherapy ensues.

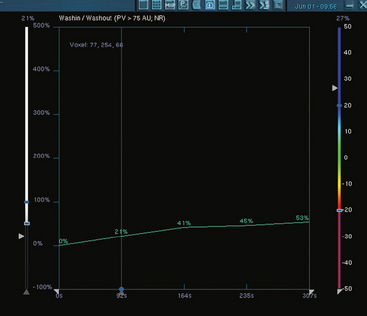

Imaging changes that successful neoadjuvant chemotherapy induces in a breast cancer are well demonstrated by this example. A responding mass can decrease in size, retaining the same basic shape, or can “break up” into smaller residual components. The intensity and pattern of enhancement change. The rapid uptake of contrast and washout demonstrated by this tumor on initial breast MRI changed to a pattern of slow, plateauing contrast accumulation.

At this writing, small-field-of-view, higherresolution, molecular breast imaging and breast-specific gamma imaging units are becoming available. Positron emission mammography may prove to be useful alternative functional means of assessing chemotherapy responses, although this validation process is currently ongoing.

This case also illustrates the imaging features of a common chemotherapy “side effect.” Many chemotherapeutic agents are myelosuppressive and may result in depressed white blood cell counts (neutropenia), predisposing patients to infection. This may result in hospitalization, delays in treatment or dose adjustments, potentially affecting the efficacy of treatment. To counteract these myelosuppressive effects, a patient may be treated with G-CSF, given with each cycle as necessary. This is a growth factor that primarily stimulates neutrophils and neutrophil precursors. Increased FDG uptake in bone marrow in patients receiving G-CSF with chemotherapy is a frequently observed PET phenomenon. This is well demonstrated in this case. A less commonly observed G-CSF–induced change is also illustrated here. The spleen displays increased FDG uptake on the postchemotherapy PET scan. This phenomenon was initially described by Sugawara and associates in a study of LABC patients undergoing chemotherapy who were evaluated before, during, and after G-CSF treatment. The increased FDG uptake in the spleen was thought to reflect changes of extramedullary hematopoiesis. These bone marrow and splenic changes regress with cessation of G-CSF treatment.

CASE 10 Complete imaging response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy

A 54-year-old postmenopausal woman with a family history of breast cancer underwent routine screening mammography, which identified developing asymmetrical density and possible architectural distortion in the right upper outer quadrant (UOQ). Mammographic spot compression confirmed the suspected abnormality, and ultrasound showed corresponding ill-defined shadowing in the 9- to 10-o’clock region (Figure 1). Stereotactic biopsy was recommended because the abnormality seemed to be better visualized mammographically than sonographically. However, the lesion could not be satisfactorily visualized for stereotactic biopsy, presumably because of the less effective compression achievable with stereotactic procedures. The hypoechoic shadowing correlate was biopsied with ultrasound guidance, confirming infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC).

On surgical, medical oncology, and radiation oncology evaluations, no palpable mass was identified. Because the size of the lesion and true extent of disease were difficult to estimate accurately based on clinical breast exam, mammography, and ultrasound, breast MRI was requested.

MRI suggested more advanced disease than suspected to that point (Figures 2, 3, 4, and 5). Multiple intensely enhancing right axillary lymph nodes were identified, which were up to 1.1 × 1.8 cm in size. The index lesion was larger than previously demonstrated, with maximal dimension estimated to be 4 cm (prior estimate by ultrasound was 2 cm). The skin of the right breast was noted to be asymmetrically thickened and edematous, with enhancement. Nearly concurrent with this, the patient noted new faint erythema of the right breast, and a tender right axillary lymph node was now palpable. She was placed on antibiotics for a possible infection. The erythema persisted, but no peau d’orange changes were ever noted. A punch skin biopsy was performed to assess for a possible inflammatory component, but showed only perivascular inflammation, with no dermal or intralymphatic carcinoma seen.

After four cycles of chemotherapy with doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) (AC), breast MRI was repeated (Figures 6 and 7). This showed a response, with the enhancing tumor reduced in size and a marked decline in intensity of enhancement. Only slow progressive enhancement was now identified. The enhancing axillary lymph nodes also resolved.

The patient elected surgical treatment with bilateral mastectomies. On the right, a sentinel lymph node was positive for malignancy, and so axillary dissection was performed. Two of four axillary lymph nodes showed tumor. The right mastectomy specimen contained residual IDC, spread over a 1.3-cm expanse. There was angiolymphatic invasion. The skin and margins were uninvolved. The left mastectomy specimen showed fibrocystic changes only.

CASE 11 IDC with cystic component; mixed response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy

A 28-year-old woman noted a palpable left breast lump while in the shower, which was subsequently confirmed by her primary care physician’s physical examination in the upper outer quadrant (UOQ). Ultrasound showed a 2.9-cm complex mass with cystic and solid components (Figure 1). Biopsy was recommended and accomplished with ultrasound guidance. The solid component was sampled with 14-gauge core needle biopsy technique and the cystic component aspirated, with the bloody aspirate sent for cytologic analysis. Pathology showed poorly differentiated invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor negative, HER-2/neu negative, and the fluid cytology showed malignant cells.

Breast MRI was obtained next and showed the left UOQ known IDC to be partially cystic (Figure 2). By MRI, the maximal dimension was 3.7 cm. An unsuspected 1-cm, intensely enhancing, circumscribed mass was found in the posterior right lateral breast (Figure 3). Subsequent workup with diagnostic mammography and ultrasound was performed. On the right, ultrasound found a 1.0- × 0.3-cm hypoechoic, oval, benign-appearing mass against the chest wall, which seemed to correspond to the MRI finding (Figure 4). Subsequent right ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy confirmed a diagnosis of fibroadenoma.

Initial consultations with surgery, medical oncology, and radiation oncology noted the tumor to be large relative to the patient’s breast size. The patient desired breast conservation, and so neoadjuvant chemotherapy with four cycles of doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) (AC) and four cycles of docetaxel (Taxotere) was elected. Preliminary staging studies with positron emission tomography (PET)/CT and enhanced body CT scans showed hypermetabolism of the peripheral solid left IDC components, but no evidence of nodal or distant metastatic disease (Figure 5). Ultrasound and breast MRI studies obtained during and at the conclusion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy showed a waxing and waning response, with improvement midway through therapy (after four cycles of AC), but partial regrowth after four cycles of Taxotere (Figures 6, 7, 8, 9, and 10). The final imaging evaluations did show overall improvement in comparison with the staging studies, despite the partial regression of the response demonstrated midway through therapy.

TEACHING POINTS

This case is interesting from multiple vantage points. Because of the patient’s youth, the workup of the palpable mass started with ultrasound, as is appropriate. At first glance with ultrasound, the cystic portions of this mass are deceptively innocent looking. However, the identification of solid components mandates further evaluation. The sonographic differential includes malignancies (intracystic carcinoma, papillary carcinoma) and benign diagnoses (post-traumatic resolving hematoma or seroma, abscess, papilloma and complex cyst). How best to sample such a complex mass, with both cystic and solid components? Options to consider include excision, cyst aspiration under ultrasound guidance, core needle biopsy with ultrasound guidance or some combination, as was performed here. Considerations at the time of image-guided sampling include whether and in which order to sample the fluid and the solid components. In this case, the solid component was sampled with 14-gauge core needle biopsy technique, followed by aspiration of the fluid, which was bloody. If aspiration was performed first, many advocate stopping the aspiration before completion if bloody fluid is obtained, with consideration of placing a marker clip if there is no visible residual. Aspiration alone with cytologic evaluation of the fluid runs the risk of a false-negative result, indicating the need for sampling of the solid component.

CASE 12 LABC, unresponsive to neoadjuvant chemotherapy

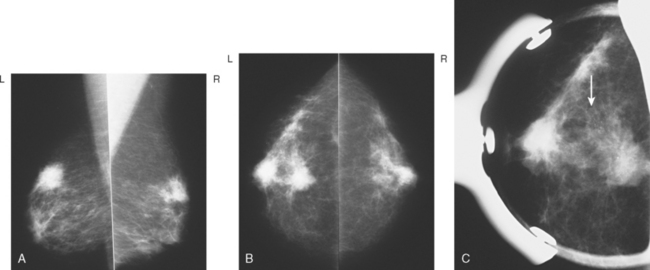

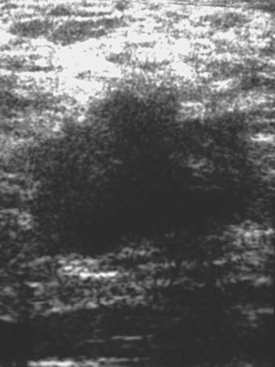

A 46-year-old premenopausal woman presented with a palpable periareolar lump for 1 month, with nipple retraction. Mammography identified a 2- to 3-cm spiculated mass at 6 o’clock (Figure 1), and ultrasound showed a corresponding shadowing 2.1-cm mass (Figure 2). Ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy confirmed invasive carcinoma with tubular and lobular features.

Breast MRI showed the mass to be even larger than previously suspected, with the maximal dimension estimated to be 6 cm (Figure 3). Initial surgical assessment was that the patient was probably not a suitable breast conservation candidate because of the size of the palpable lump and proximity to the nipple. However, the patient desired an attempt at lumpectomy, and opted for neoadjuvant chemotherapy. After four cycles of chemotherapy with doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) (AC), imaging re-evaluation with breast MRI was obtained. Only a modest response was noted, with the maximal dimension of the persistent spiculated mass estimated at 4.5 cm. Repeat breast MRI, 2 months later after three cycles of docetaxel (Taxotere), showed no change, with a persistent, intensely enhancing residual 4.5-cm mass (Figures 4, 5, and 6). By physical examination, the mass size was estimated at 2 cm. Mastectomy was again recommended, and declined. Following ultrasound-guided needle localization, a lumpectomy was performed. The specimen contained a 3.3-cm mixed infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC) with ductal and lobular features, estrogen receptor positive, progesterone receptor negative, and HER-2/neu negative. The medial margin was positive, and multiple additional margins were close. One of two lymph nodes was positive, with a 2-mm focus of tumor.

Subsequent mastectomy showed two microscopic foci of IDC (largest, 2 mm) and negative margins. Right chest wall, supraclavicular, and peripheral lymphatics were radiated subsequently. The patient was started on tamoxifen, which was not well tolerated, and switched to anastrozole (Arimidex) and subsequently to exemestane (Aromasin). No evidence of recurrence has been identified 2.5 years after diagnosis.

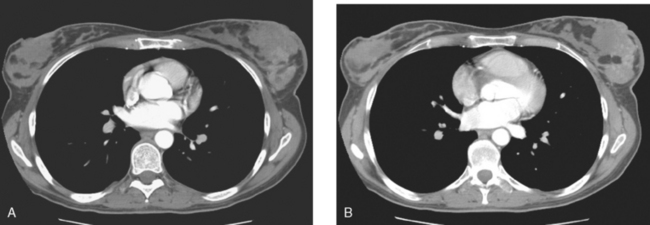

CASE 13 Rapidly progressive inflammatory breast cancer, unresponsive to chemotherapy

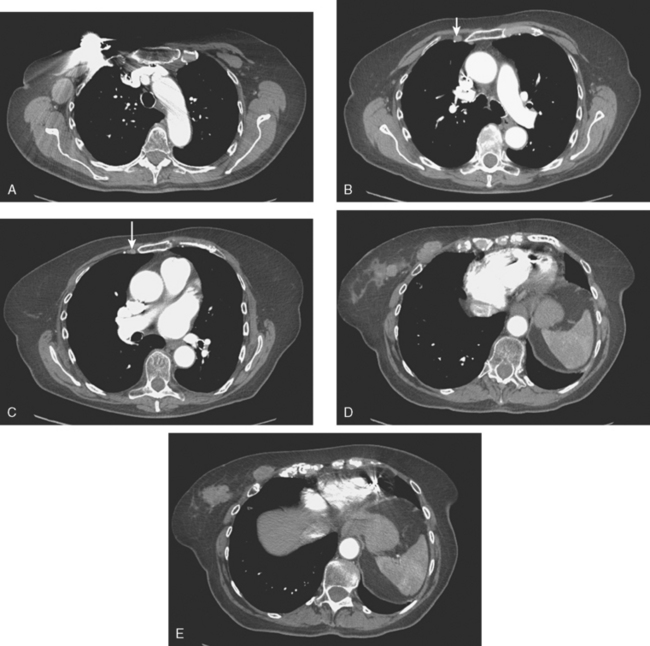

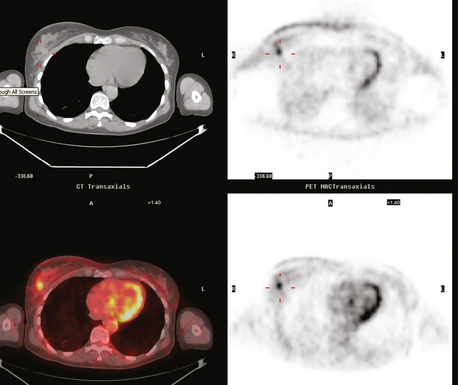

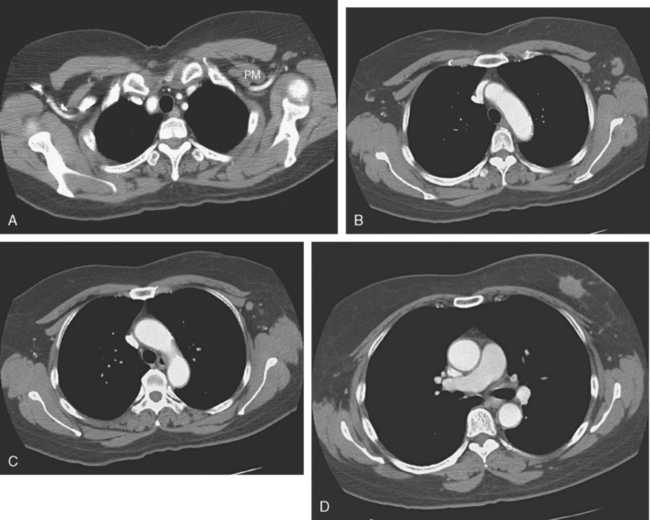

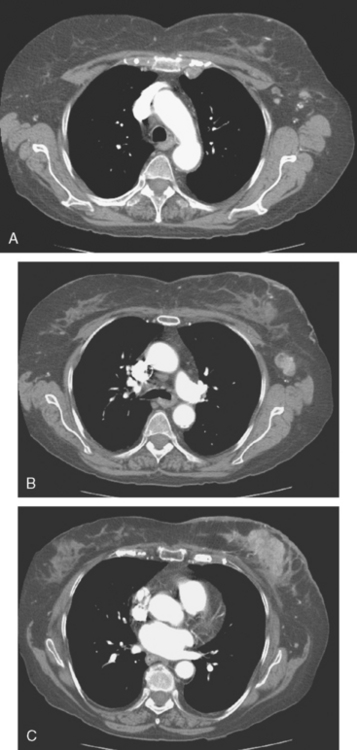

The CT scan showed a large, dominant, enhancing, irregularly marginated mass in the left breast, which was a dramatic change from a CT scan performed 4 months before (Figures 1 and 2). Palpation-guided core needle biopsy confirmed an infiltrating ductal carcinoma (IDC), estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor negative, HER-2/neu negative. Periareolar erythema was noted, as well as palpable axillary lymph nodes. Chemotherapy was started. While receiving chemotherapy, a bone scan was obtained to evaluate right shoulder and forearm pain. Although no findings particularly suggestive of bony metastases were seen, the large left breast cancer was visualized (Figure 3).

Three months later, after four cycles of doxorubicin (Adriamycin) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) (AC) with little clinical improvement, a repeat CT scan was obtained (Figure 4). This showed the left breast mass to be little changed, with worsening of skin thickening and enhancement. Progressive axillary and internal mammary adenopathy was noted.

FIGURE 4 Repeat CT scan, 3 months after Figure 1 and after four cycles of AC chemotherapy (A to C, from above to below). A, Four mildly prominent (more notable for increased number and asymmetry than size) left axillary lymph nodes are seen, as well as a pathologically enlarged left internal mammary lymph node. B, A pathologically enlarged left axillary lymph node is seen at this level. Note diffuse increase in reticulation and density of the left breast and left breast skin thickening. C, The dominant enhancing left breast mass is still bulky, and there is pronounced increased skin thickening and enhancement.

Docetaxel (Taxotere) was administered. After three cycles, worsened erythema and induration were noted. A breast MRI was obtained to more accurately assess the extent of disease (Figures 5 and 6). A skin biopsy was obtained, showing multifocal intralymphatic carcinoma. Palliative radiation therapy was administered for local control. Toward the end of radiation, the patient developed right upper quadrant pain. CT scan showed innumerable new hypovascular liver metastases (Figure 7). The patient died less than a month later, 7 months after the inflammatory breast cancer (IBC) diagnosis.

TEACHING POINTS

CT is an unconventional choice to assess the response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. In this case, this patient had a longstanding history of an indolent, multiply recurrent RCC, for which she was regularly followed with CT. (Her initial diagnosis of RCC was 15 years before, with surgically resected regional recurrences 5 and 2 years before.) The choice of CT to follow this patient’s chemotherapy response presumably reflects her oncologist’s familiarity with CT, as well as that the IBC was large and well seen on CT. CT does allow evaluation of regional nodal basins well, with the evaluation directed to detection of interval change and the presence or absence of nodes, and assessment of their size, shape, and density. In some nodal basins, like the internal mammaries, normal lymph nodes are not routinely seen, and so visualization of any lymph nodes is suspicious. In other regions, such as the axilla, normal lymph nodes are routinely visualized, and so the assessment is based more on comparison with the opposite side for asymmetry, such as an abnormally increased number of visualized nodes, disproportionately sized nodes (even if not clearly “enlarged”), or nodes with abnormal morphology (rounded, enlarged, effaced fatty hilus, fuzzy margins).

IBC is aggressive and confers a poor prognosis. This patient had no appreciable response to chemotherapy, and clinically progressed while receiving it. Liver metastases were a late, terminal development in the rapid course of this patient’s disease. IBC patients who do respond to primary systemic therapy (neoadjuvant chemotherapy) are generally then treated with mastectomy and postoperative radiation therapy to the chest wall and regional node basins.

CASE 14 LABC, good response by imaging to neoadjuvant chemotherapy, but significant residual pathologic disease; imaging-guided tailored lumpectomy

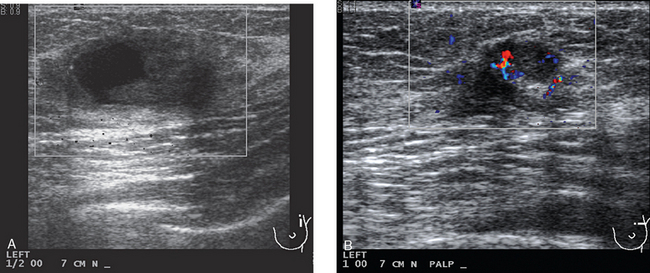

A 41-year-old woman noted a left breast lump after rolling over in bed. A palpable mass was confirmed by her primary care physician. Clinical estimates of the size of the mass were on the order of 4 cm, or a T2 lesion. Palpation-guided sampling of the abnormality by surgery did not yield a definitive diagnosis. Subsequent breast imaging workup with mammography and ultrasound confirmed a highly suspicious mass on both, accompanied by suspicious, enlarged axillary lymph nodes (Figures 1, 2, and 3). By ultrasound, the mass measured up to 3.5 cm. Ultrasound-guided biopsy of the breast mass proved the lesion to be grade 6/9 invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC), estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor positive, HER-2/neu negative. Sonogram-guided axillary node fine-needle aspiration showed cancer of breast primary origin.

FIGURE 2 Adjacent to the discrete mass depicted in Figure 1 was a less well-defined area of abnormal echotexture with shadowing and increased vascularity.

The patient desired breast conservation. Because of the large size of her mass, neoadjuvant chemotherapy was planned in hopes of shrinking the tumor and improving the cosmetic outcome. Her staging evaluation was completed with enhanced body CT scans, positron emission tomography (PET)/CT, and breast MRI. The breast MRI showed a much larger lesion than suspected previously, measuring 9.5 × 4 cm, occupying much of left lateral breast (Figure 4). The dominant mass consisted of multiple contiguous components, which enhanced intensely, with washout.

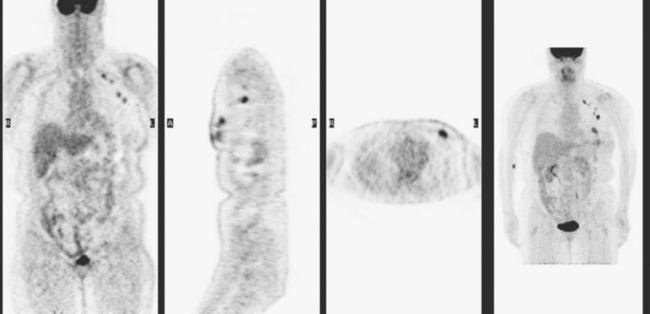

PET scans showed the dominant left breast cancer to be hypermetabolic and accompanied by multiple metabolically active axillary lymph nodes, as well as subtle evidence of probable supraclavicular uptake in small lymph nodes (Figures 5, 6, and 7). No distant metastases were found by CT or PET.

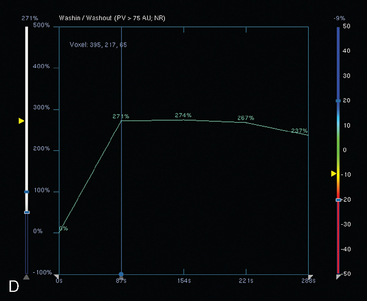

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, consisting of four cycles of doxorubicin (Adriamycin) plus cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan) (AC) and four cycles of docetaxel (Taxotere), was given. The patient’s response was assessed halfway through chemotherapy with repeat breast MRI (Figure 8). A response to chemotherapy was seen, with shrinkage of the tumor to 6.2 × 2.9 cm, with less intense enhancement. The pattern of enhancement also changed, with no washout seen and an overall plateauing enhancement pattern. Restaging studies with ultrasound and breast MRI at the conclusion of chemotherapy showed further improvement (Figures 9 and 10A). On ultrasound, a residual 7-mm mass could be identified. On MRI, there was further contraction of the mass. It still showed an elongated configuration, and now measured 5.8 × 1 cm. The intensity and quality of the enhancement also had improved, with progressive and less intense enhancement only.

FIGURE 8 Repeat breast MRI, 3 months after diagnosis, after four cycles of AC chemotherapy. A, Axial MIP (compare to Figure 4A) shows marked reduction in volume and intensity of enhancement of the multifocal IDC. B, Enhanced, subtracted, axial image from the dynamic series (compare with Figure 4C) shows contraction of the mass, which is reduced to a beaded irregularly shaped residual. C, DynaCAD color map of the enhancement, with a region of interest placed on the posterior enhancing component. D, Graphical display of this kinetic data (change in signal intensity–time curve) shows a plateauing pattern of enhancement.

FIGURE 9 Third breast MRI, obtained two additional months later, after completion of four cycles of Taxotere: A, Axial MIP view (compare with Figures 4A and 8A) shows clumped residual foci of enhancement in the left lateral breast. The MRI appearance is much improved. B, Enhanced, subtracted, axial image from the dynamic series (compare with Figures 4C and 8B) shows clusters of clumped foci of enhancement. Only progressive enhancement was now identified.

FIGURE 10 Breast ultrasound, after completion of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, 6 months after the study in Figure 1. A, The smaller, hypoechoic residual mass, now measuring 7 mm, continues to show angular margination. B, Under ultrasound guidance, a clip is placed to mark the residual mass. The needle can be seen traversing the mass from the right. C, After clip deployment, the hyperechoic clip can be seen against the background of the hypoechoic residual mass. Care needs to be taken to try to deploy ultrasound-placed clips where they will contrast with more hypoechoic tissue to aid in their visualization.

Breast conservation had been planned. A clip was placed into the small residual mass seen by ultrasound (see Figures 10B and C). Based on correlation with MRI, it seemed unlikely that localization of this one component would result in clear margins without additional guidance. Accordingly, clips were placed under MRI guidance at the anterior and posterior extremes of the residual enhancement (Figure 11). These were needle-localized by placement of two localizing wires in proximity to the MRI-placed clips (Figure 12).

TEACHING POINTS

Not all breast cancers respond to neoadjuvant chemotherapy. To identify those patients who are not responding and may benefit from a change in therapeutic approach, both clinical and imaging monitoring is performed periodically during neoadjuvant chemotherapy. Here again, breast MRI has been shown to be the most accurate of the current breast imaging techniques in assessing responses to treatment. Although better than mammography and ultrasound, breast MRI is not perfect and can both under- and overestimate the amount of residual disease. Even patients with complete imaging responses may have microscopic disease at histology. Patients like this, with what appeared to be an excellent response by MRI, can still have a significant disease burden. In this case, the actual dimension of the measured residual enhancement correlated fairly well with the maximal dimension of the residual mass at partial mastectomy.

Boetes C, Mus RD, Holland R, et al. Breast tumors: comparative accuracy of MR imaging relative to mammography and US for demonstrating extent. Radiology. 1995;197:743-747.

Dash N, Chafin SH, Johnson RR, et al. Usefulness of tissue marker clips in patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173:911-917.

Rosen EL, Blackwell KL, Baker JA, et al. Accuracy of MRI in the detection of residual breast cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2003;181:1275-1282.

Yeh E, Slanetz P, Kopans DB, et al. Prospective comparison of mammography, sonography, and MRI in patients undergoing neoadjuvant chemotherapy for palpable breast cancer. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2005;184:868-877.