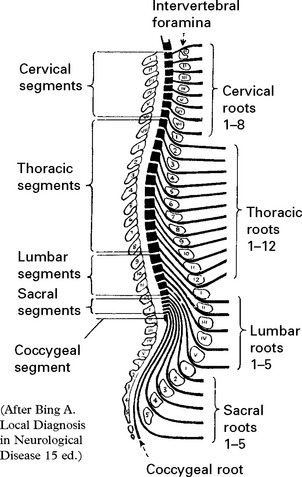

SECTION IV LOCALISED NEUROLOGICAL DISEASE AND ITS MANAGEMENT B. SPINAL CORD AND ROOTS

SPINAL CORD AND ROOTS

Disorders localised to the spinal cord or nerve roots are detailed below, but note that many diffuse neurological disease processes also affect the cord (see Section V, e.g. multiple sclerosis, Friedreich’s ataxia).

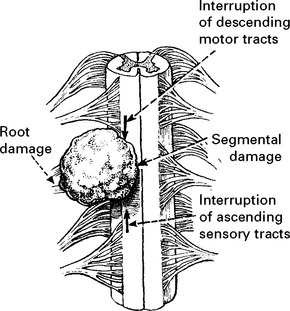

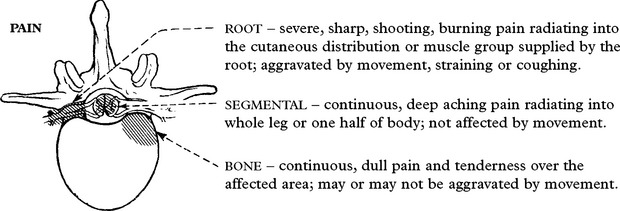

SPINAL CORD AND ROOT COMPRESSION – NEUROLOGICAL EFFECTS

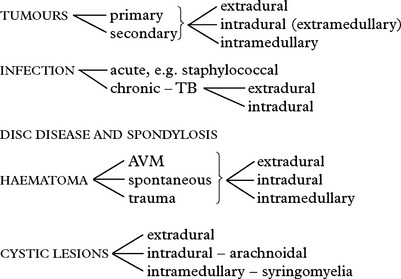

LATERAL COMPRESSIVE LESION

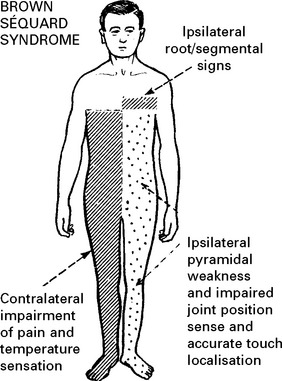

Long tract – signs and symptoms Partial (Unilateral) cord lesion

UPPER MOTOR NEURON (u.m.n.) signs (maximal on side of lesion):

Damage to sympathetic pathways in the T1 root or cervical cord causes an ipsilateral Horner’s syndrome (page 145).

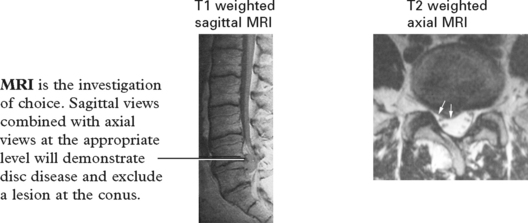

SPINAL CORD AND ROOT COMPRESSION – INVESTIGATIONS

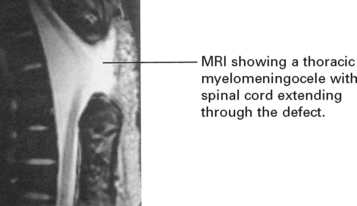

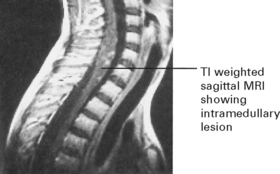

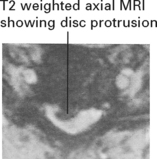

MRI

MRI differentiates a syrinx (page 401) or a cystic swelling within the spinal cord from a solid intramedullary tumour (page 400).

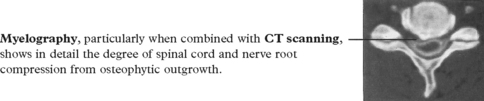

MYELOGRAPHY

Lesions in the lumbar and sacral regions require a ‘radiculogram’, outlining the lumbosacral roots.

SPINAL CORD AND ROOT COMPRESSION

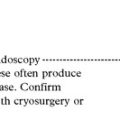

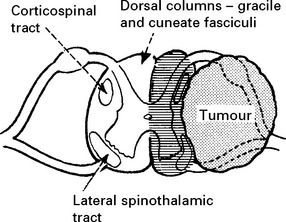

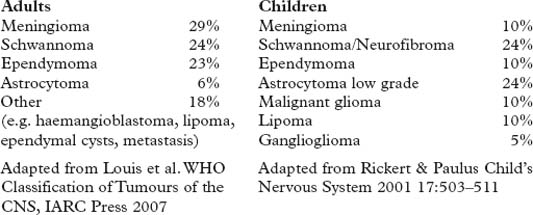

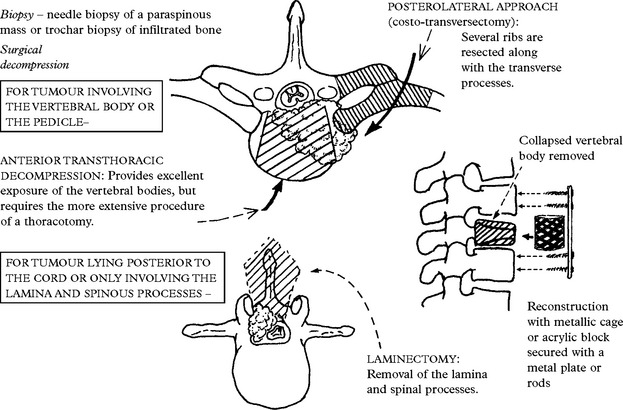

TUMOURS

Pathology: The pathological features of spinal tumours match those of their intracranial counterparts (see page 303).

METASTATIC TUMOUR

Occurs in 5% of all cancer patients and accounts for 50% of adult acute myelopathies.

Primary site: Usually breast, lung, prostate, kidney or myeloma (see below).

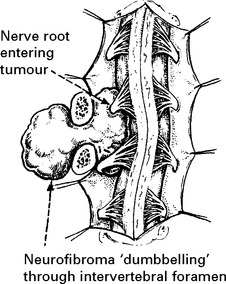

SCHWANNOMA/NEUROFIBROMA

Neurofibromas are identical apart from their microscopic appearance (page 304) and their association with multiple neurofibromatosis (Von Recklinghausen’s disease NF1 – see page 561) – look for café au lait patches in the skin.

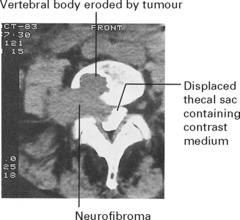

MRI or CT myelography identifies an intradural/extramedullary lesion. Axial views will delineate any extraspinal extension (see page 395). Complete operative removal is feasible but the nerve root of origin is inevitably sacrificed. Overlap from adjacent nerve roots usually minimises any resultant neurological deficit.

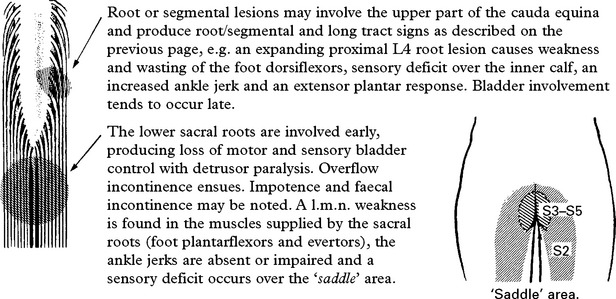

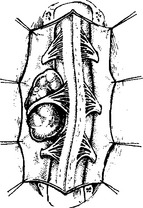

EPENDYMOMA OF THE CAUDA EQUINA

Over 50% of spinal ependymomas occur around the cauda equina and present with a central cauda equina syndrome (page 394). Operative removal combined with radiotherapy usually gives good long-term results, although metastatic seeding occasionally occurs through the CSF.

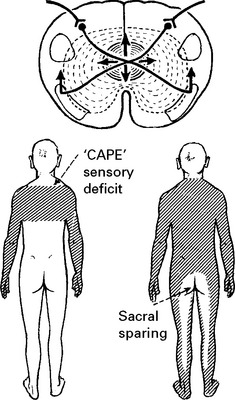

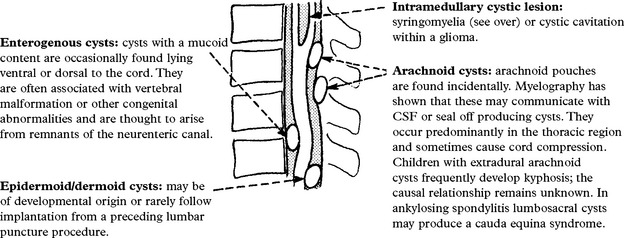

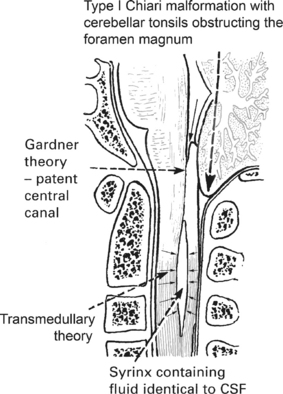

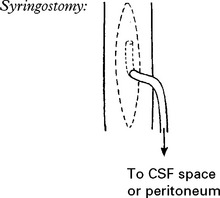

SYRINGOMYELIA

Syringomyelia is the acquired development of a cavity (syrinx) within the central spinal cord. The lower cervical segments are usually affected, but extension may occur upwards into the brain stem (syringobulbia, see page 381) or downwards as far as the filum terminale.

The cavitation appears to develop in association with obstruction:

Clinical features

Investigations

MRI is the investigation of choice (see page 380). This will demonstrate the syrinx with any associated Chiari malformation and exclude intramedullary tumour.

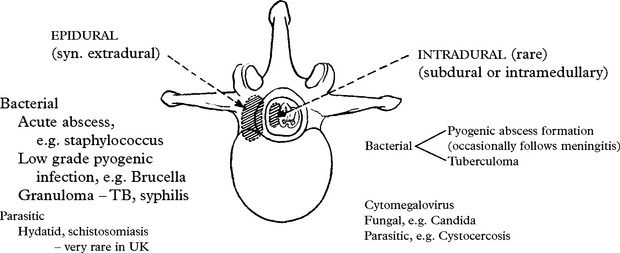

ACUTE EPIDURAL ABSCESS

Organism: Staphylococcus aureus is the most common agent (90% of cases).

Spread: Haematogenous, e.g. from a boil or furuncle, or direct from vertebral osteomyelitis.

As the abscess extends upwards, the sensory level may rise.

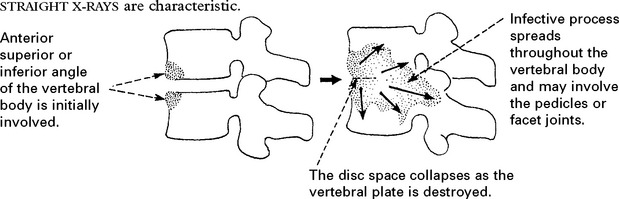

Investigations: Straight X-ray may or may not show an associated osteitis or discitis.

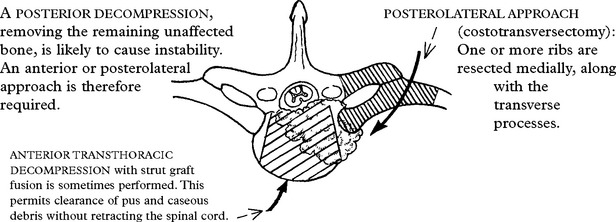

SPINAL TUBERCULOSIS (Pott’s disease of the spine)

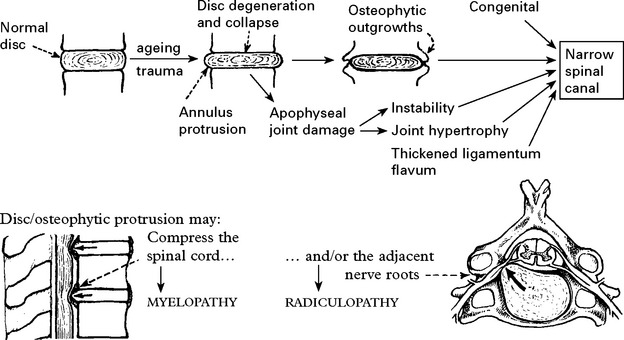

DISC PROLAPSE AND SPONDYLOSIS

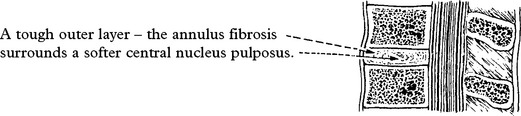

Intervertebral discs act as shock absorbers for the bony spine.

LUMBAR DISC PROLAPSE

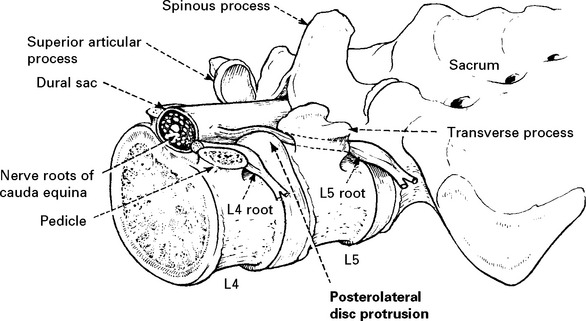

Lumbar disc lesions may occur at any level but L4/5 and L5/S1 are the commonest sites (95%).

CLINICAL FEATURES

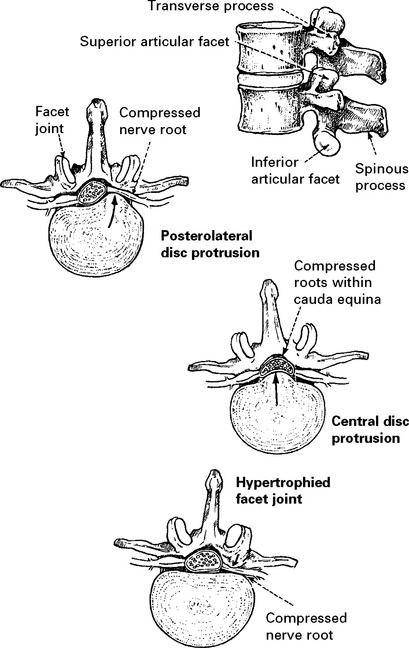

Posterolateral disc protrusion

Sensory symptoms: Numbness or paraesthesia occur in the distribution of the affected root.

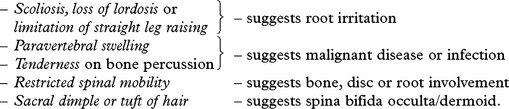

‘MECHANICAL’ SIGNS: Spinal movements are restricted, scoliosis is often present and is related to spasm of the erector spinae muscles, and the normal lumbar lordosis is lost.

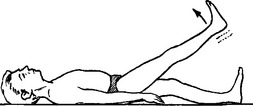

Reverse leg raising (femoral stretch)

Tests for irritation of higher nerve roots (L4 and above)

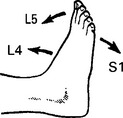

NEUROLOGICAL DEFICIT: Depends on the predominant root involved:

L4 – Quadriceps wasting and weakness; sensory impairment over medial calf; impaired knee jerk.

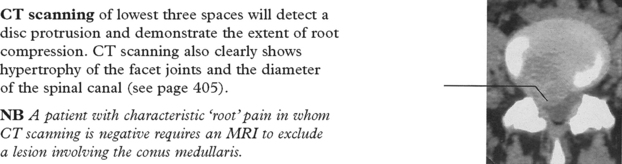

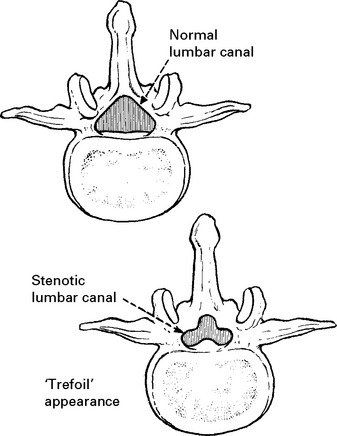

INVESTIGATION

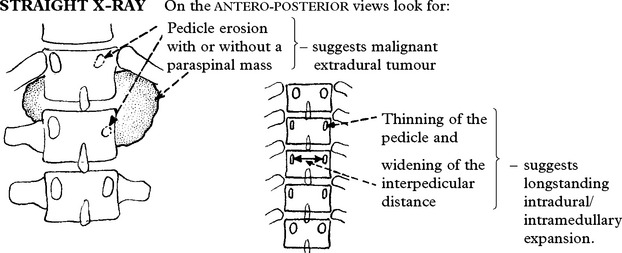

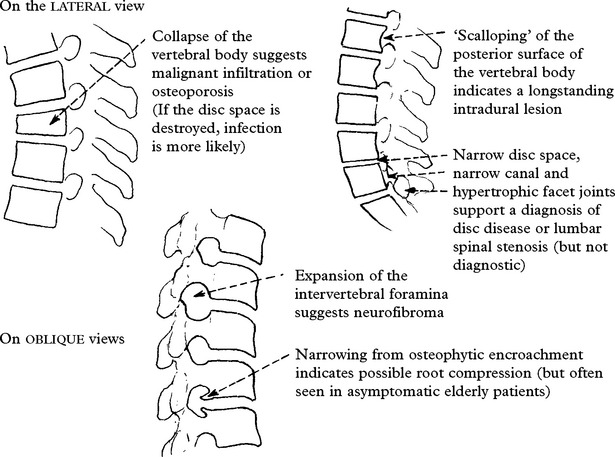

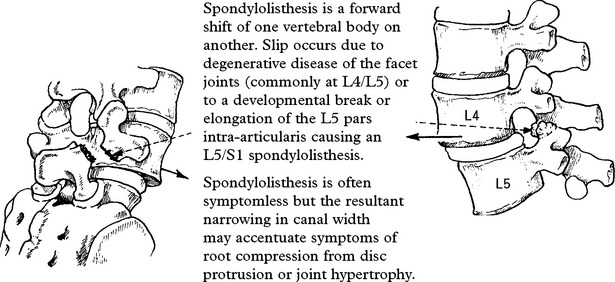

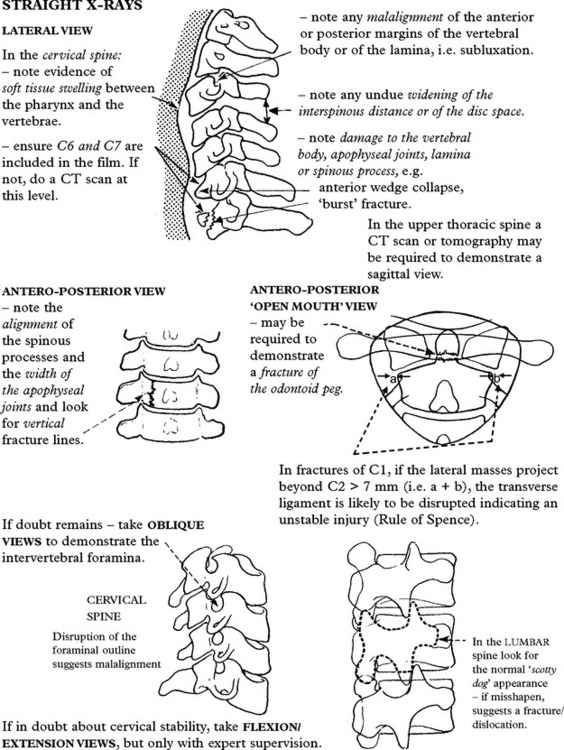

Straight X-ray of lumbosacral spine is of limited benefit in the investigation of lumbar disc disease – it may show loss of a disc space or an associated spondylolisthesis (see p. 410). Straight X-rays are important in excluding other pathology such as metastatic carcinoma.

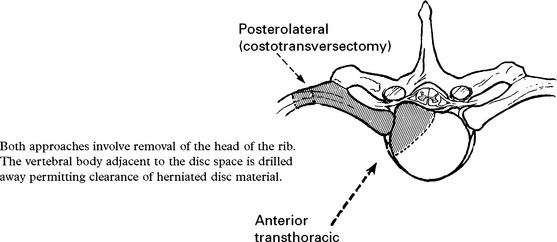

THORACIC DISC PROLAPSE

This occurs rarely (0.2% of all disc lesions) due to the relative rigidity of the thoracic spine.

CERVICAL SPONDYLOSIS

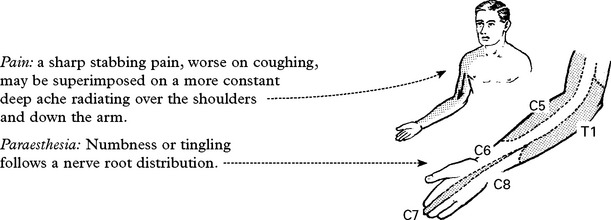

CLINICAL FEATURES

Radiculopathy

INVESTIGATION

MANAGEMENT

Conservative

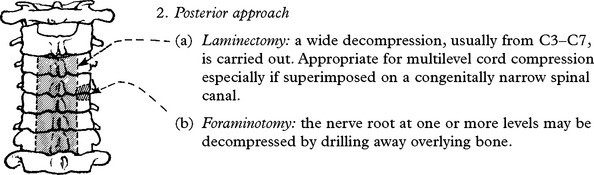

Operative techniques

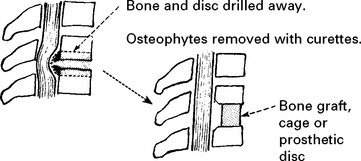

1. Anterior decompression and fusion

A core of bone and disc is removed along with the osteophytic projections. Although not essential, some insert a bone graft from the iliac crest, or a metallic cage (see page 398) to promote fusion. More recently prosthetic discs have become available. There is no evidence that any one technique produces better results than another.

Most suitable for root or cord compression from an anterior protrusion at one or two levels.

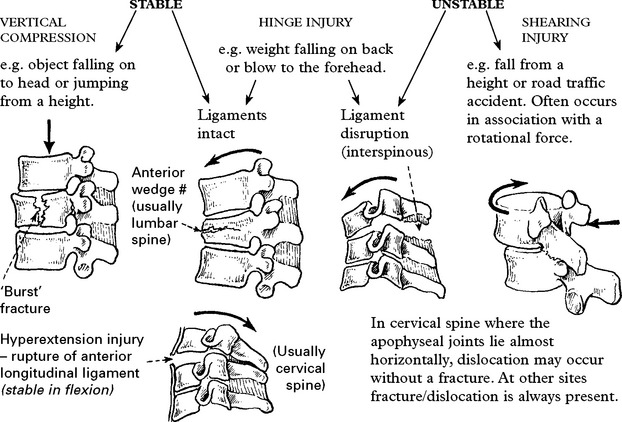

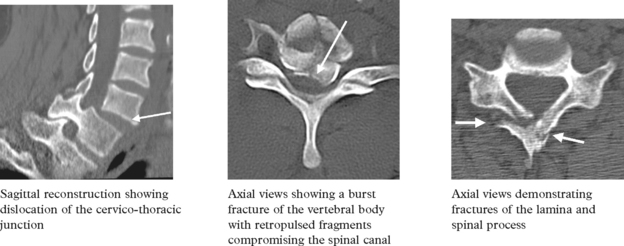

SPINAL TRAUMA

SPINAL TRAUMA – INVESTIGATIONS/MANAGEMENT

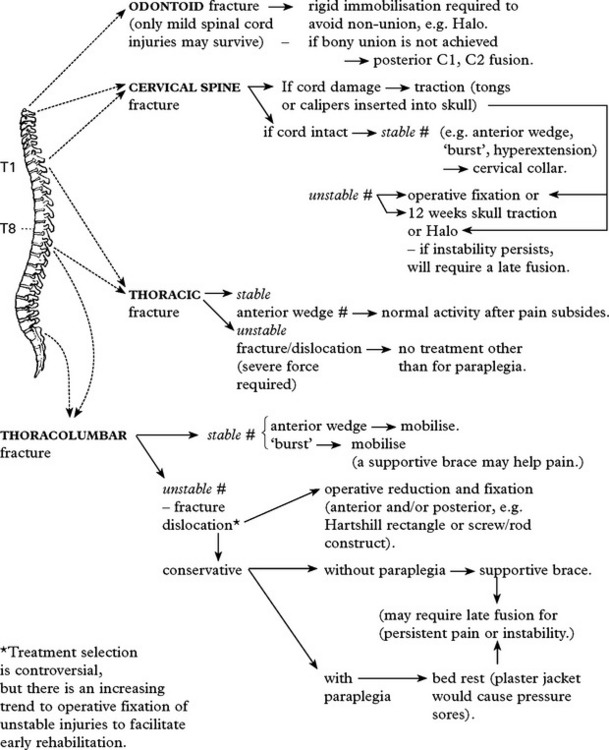

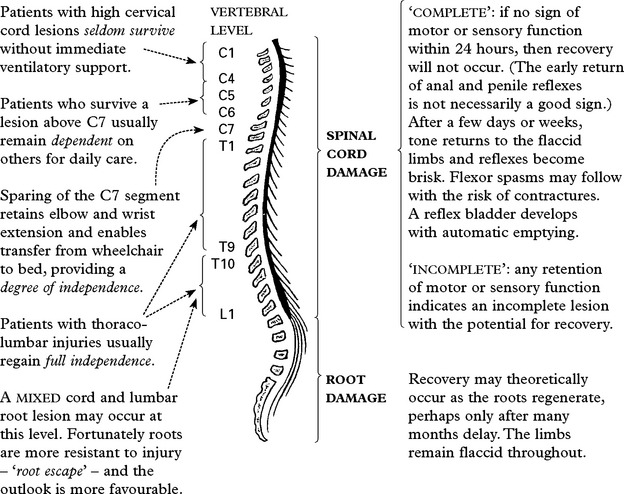

MANAGEMENT

Management depends on the site and stability of the lesion, but basic principles apply.

SPINAL TRAUMA – MANAGEMENT

Management of the paraplegic patient

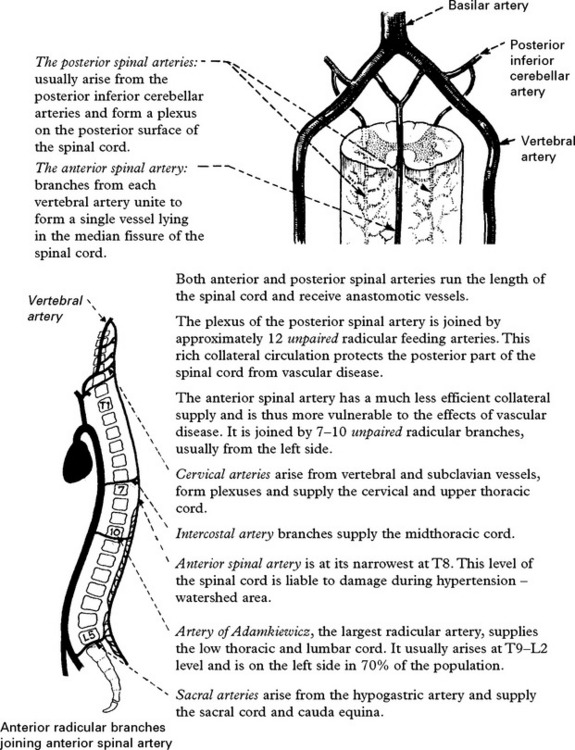

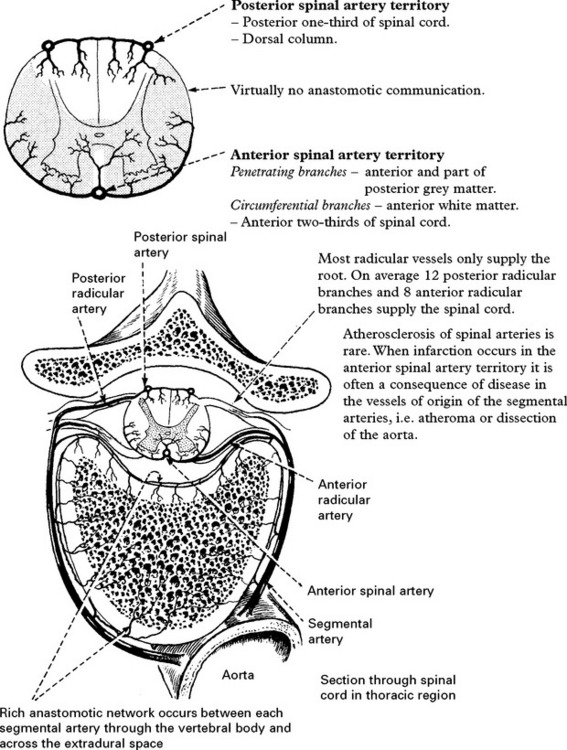

VASCULAR DISEASES OF THE SPINAL CORD

SPINAL CORD INFARCTION

Anterior spinal artery syndrome

The level at which infarction occurs determines symptoms and signs.

Characteristic features include:

A pure conus syndrome (page 394) occasionally occurs.

Investigative approach

aortic (large) vessel diseases

Treatment is symptomatic and the outcome variable.

Posterior spinal artery syndrome

– Loss of tendon reflexes/motor weakness

– Loss of joint position sense.

A rapid ‘total’ cord syndrome with poor outcome often associated with pelvic sepsis.

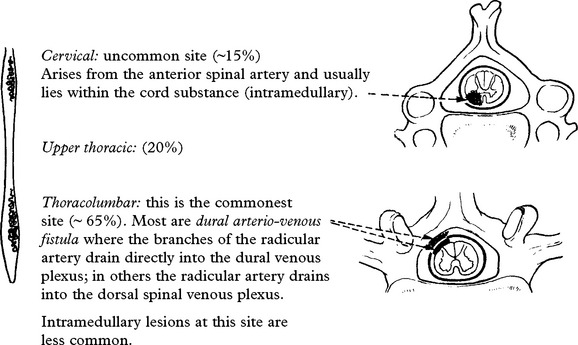

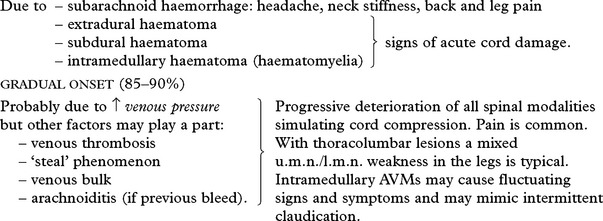

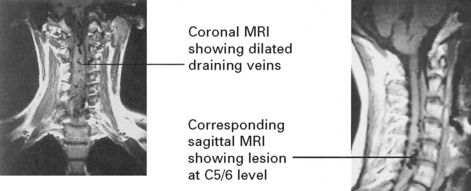

SPINAL ARTERIOVENOUS MALFORMATION (Angiomatous malformation)

Management

| Techniques: | Embolisation |

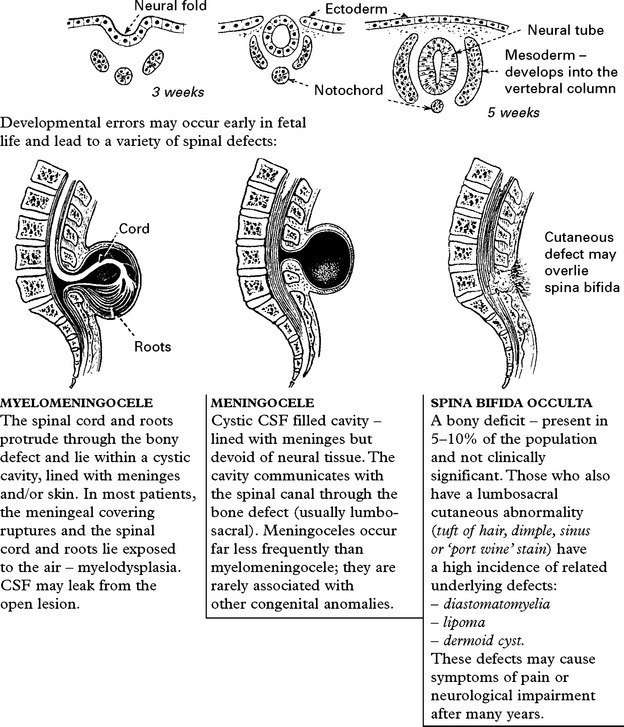

SPINAL DYSRAPHISM

Embryology

Site: 80% occur in the lumbosacral region.

Associated abnormalities: Hydrocephalus, Chiari type II, aqueduct forking.

Antenatal diagnosis

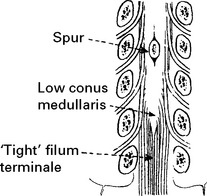

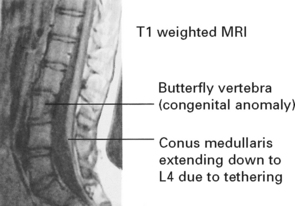

TETHERED CORD: in some patients the conus medullaries lies well below its normal level (L1), ‘tethered’ by the filum terminale. Since vertebral growth proceeds more rapidly than growth of the spinal cord, tethering may produce progressive back pain or neurological impairment as the cord is stretched.

days spastic

days spastic days hyper-reflexia and extensor plantar responses

days hyper-reflexia and extensor plantar responses