Local Anaesthetic Techniques

FEATURES OF LOCAL ANAESTHESIA

Avoidance of the adverse effects of general anaesthesia. These may range from relatively minor postoperative nausea and vomiting, sore throat or myalgia to major issues such as respiratory impairment, awareness, airway complications or aspiration pneumonitis. In addition, the management of many patients with significant medical co-morbidity such as diabetes, obesity, or chronic pulmonary disease, can be improved or simplified. In elderly patients, acute perioperative cognitive impairment may be limited by reducing or avoiding psychoactive drugs and maintaining contact with their surroundings.

Avoidance of the adverse effects of general anaesthesia. These may range from relatively minor postoperative nausea and vomiting, sore throat or myalgia to major issues such as respiratory impairment, awareness, airway complications or aspiration pneumonitis. In addition, the management of many patients with significant medical co-morbidity such as diabetes, obesity, or chronic pulmonary disease, can be improved or simplified. In elderly patients, acute perioperative cognitive impairment may be limited by reducing or avoiding psychoactive drugs and maintaining contact with their surroundings.

Postoperative analgesia. Local anaesthetic techniques can be used to provide effective prolonged postoperative analgesia whilst avoiding the systemic effects of other analgesic drugs, especially opioids. This can be provided using long-acting agents or by utilizing continuous catheter techniques, either neuraxial or peripheral. Some patients may be distressed by the accompanying numbness and motor block, but adequate preoperative explanation should minimize this concern. In addition, it is important that both nursing staff and patient are aware of the risk of tissue damage to any blocked area whether from direct trauma or indirect pressure from poor positioning or prolonged immobility. Simple techniques such as supporting the arm in a sling after brachial plexus block may help prevent injury and encourage earlier mobilization.

Postoperative analgesia. Local anaesthetic techniques can be used to provide effective prolonged postoperative analgesia whilst avoiding the systemic effects of other analgesic drugs, especially opioids. This can be provided using long-acting agents or by utilizing continuous catheter techniques, either neuraxial or peripheral. Some patients may be distressed by the accompanying numbness and motor block, but adequate preoperative explanation should minimize this concern. In addition, it is important that both nursing staff and patient are aware of the risk of tissue damage to any blocked area whether from direct trauma or indirect pressure from poor positioning or prolonged immobility. Simple techniques such as supporting the arm in a sling after brachial plexus block may help prevent injury and encourage earlier mobilization.

Preservation of consciousness during surgery. The ability to assess neurological status continuously may be an advantage in patients with a head injury, diabetes or those undergoing carotid endarterectomy. Patient positioning may be safer, more comfortable and damage to pressure areas or joints avoided if the patient is awake. Airway and neck manipulation can be avoided; this may be especially important in a patient with severe rheumatoid arthritis or an unstable cervical spine. The awake patient undergoing caesarean section under regional anaesthesia is able to protect her own airway and experience the birth of the child.

Preservation of consciousness during surgery. The ability to assess neurological status continuously may be an advantage in patients with a head injury, diabetes or those undergoing carotid endarterectomy. Patient positioning may be safer, more comfortable and damage to pressure areas or joints avoided if the patient is awake. Airway and neck manipulation can be avoided; this may be especially important in a patient with severe rheumatoid arthritis or an unstable cervical spine. The awake patient undergoing caesarean section under regional anaesthesia is able to protect her own airway and experience the birth of the child.

Sympathetic blockade and attenuation of the stress response to surgery.

Sympathetic blockade and attenuation of the stress response to surgery.

Improved gastrointestinal motility and reduced nausea and vomiting. This can allow earlier feeding and more rapid mobilization and discharge.

Improved gastrointestinal motility and reduced nausea and vomiting. This can allow earlier feeding and more rapid mobilization and discharge.

COMPLICATIONS OF LOCAL ANAESTHESIA

It encourages careful, meticulous practice

It encourages careful, meticulous practice

It provides the anaesthetist with valuable information on block onset and efficacy

It provides the anaesthetist with valuable information on block onset and efficacy

It alerts the anaesthetist to early complications such as inadvertent intravenous injection or intraneural injection.

It alerts the anaesthetist to early complications such as inadvertent intravenous injection or intraneural injection.

Local Anaesthetic Toxicity

Clinical Features and Treatment

The clinical features and treatment of LA toxicity are described in Chapter 4.

Prevention

The following precautions are useful to minimize the risk of LA toxicity:

GENERAL MANAGEMENT

Selection of Technique

Resuscitation Equipment

an anaesthetic breathing system through which oxygen may be administered under pressure via a face mask or tracheal tube

an anaesthetic breathing system through which oxygen may be administered under pressure via a face mask or tracheal tube

a laryngoscope with two sizes of blade, a range of tracheal tubes and an introducer

a laryngoscope with two sizes of blade, a range of tracheal tubes and an introducer

a table which may be rapidly tilted head-down

a table which may be rapidly tilted head-down

intravenous cannulae and fluids

intravenous cannulae and fluids

thiopental or propofol to control convulsions

thiopental or propofol to control convulsions

drugs to treat bradycardia or hypotension, especially atropine, ephedrine and metaraminol or phenylephrine

drugs to treat bradycardia or hypotension, especially atropine, ephedrine and metaraminol or phenylephrine

lipid emulsion 20% for treating serious systemic toxicity (see Ch 4).

lipid emulsion 20% for treating serious systemic toxicity (see Ch 4).

Regional Block Equipment

Needles

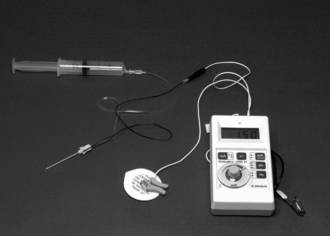

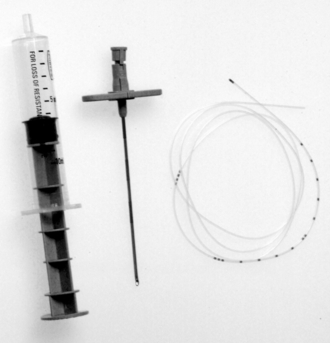

The use of very fine spinal needles (26G) has significantly reduced the incidence of post-spinal headache as has the use of pencil-point 25G Whitacre and 24G Sprotte needles (Fig. 24.1A). The 27G Whitacre needles appear to be associated with the lowest incidence of post-spinal headache but confident and successful use of these needles requires greater expertise than is needed for the use of larger needles. For peripheral blocks, short-bevelled needles allow greater tactile appreciation of fascial planes and appear to reduce the likelihood of nerve damage. A variety of insulated needles are available for plexus and peripheral nerve blockade using a nerve stimulator (Fig. 24.1B). Ultrasound needle visibility may be improved by using echogenic needles which have ‘corner stone’ reflectors positioned at the distal end of the cannula shaft (Fig. 24.11C).

Immobile Needle Technique

For plexus and major nerve blocks, local anaesthetic drug is drawn into labelled syringes and connected to the block needle by a short length of tubing (Fig. 24.2). This allows the anaesthetist to hold the needle steady while aspiration tests are performed and syringes changed. The system must be primed to prevent air embolism and also to avoid image artefact when using ultrasound-guidance.

Catheters

Continuous administration of local anaesthetic drugs has been made possible by the development of high-quality catheters, which are introduced through a needle (or occasionally over a needle; Fig 24.1A) and may be left in position for hours or even days. Careful fixation is essential to maintain the position of the catheter in the postoperative period. Catheters, in particular spinal (subarachnoid) catheters, should be labelled clearly to prevent accidental overdosage.

Nerve Stimulators

Few anaesthetists now aim to deliberately elicit paraesthesiae when performing a major nerve block; many still use the nerve stimulator (Fig. 24.2) but an increasing number now use ultrasound-guidance. It is important to explain to the patient the sensation elicited by nerve stimulation. It causes little discomfort unless the contracting muscle crosses a fracture site, when duration of stimulation should be kept to the absolute minimum necessary to confirm needle position. The incidence of paraesthesia with short-bevelled insulated needles is very low because of their ability to stimulate without direct neural contact. They are also more likely to displace nerves rather than penetrate them.

CENTRAL NERVE BLOCKS

Physiological Effects of Subarachnoid Block

Prevention of Hypotension

Bradycardia may occur because of:

neurogenic factors, particularly in awake patients, i.e. vasovagal syndrome

neurogenic factors, particularly in awake patients, i.e. vasovagal syndrome

paradoxical Bezold-Jarisch reflex; decreased venous return and heightened sympathetic tone leads to forceful contraction of a near empty left ventricle, with consequent parasympathetically mediated arterial vasodilatation and bradycardia

paradoxical Bezold-Jarisch reflex; decreased venous return and heightened sympathetic tone leads to forceful contraction of a near empty left ventricle, with consequent parasympathetically mediated arterial vasodilatation and bradycardia

Indications for Subarachnoid Block

Types of Surgery

Urology: Subarachnoid block is commonly employed for urological procedures such as transurethral prostatectomy, but it should be remembered that a block to T10 is required for surgery involving bladder distension. Perineal and penile operations may also be carried out using a low ‘saddle block’, peripheral blockade or caudal anaesthesia.

Gynaecology: Minor procedures such as dilatation and curettage may be performed reliably with a block to T10. Pelvic floor surgery and vaginal hysterectomy may also be carried out readily with an SAB extending to T6, but for procedures requiring laparoscopic assistance, general anaesthesia is usually necessary.

Obstetrics: The widespread introduction of the pencil-point spinal needle with a reduction in the incidence of post-lumbar-puncture headache has led to the common use of SAB in obstetric practice to the extent that this is considered the technique of choice for the majority of elective caesarean sections and a large proportion of emergency ones. SAB may also be used for evacuation of retained products of conception, avoiding the risks of general anaesthesia. Further details of obstetric practice are discussed in Chapter 35.

Contraindications to Subarachnoid Block and Epidural Anaesthesia

Most contraindications are relative, but the following are best regarded by the trainee as absolute:

severe stenotic valvular heart disease and in particular aortic stenosis – the patient may be unable to compensate for vasodilatation because of a fixed cardiac output

severe stenotic valvular heart disease and in particular aortic stenosis – the patient may be unable to compensate for vasodilatation because of a fixed cardiac output

pre-eclamptic toxaemia – epidural block is used with great benefit in this condition but a platelet count < 100 × 109 L–1 usually precludes epidural or subarachnoid anaesthesia

pre-eclamptic toxaemia – epidural block is used with great benefit in this condition but a platelet count < 100 × 109 L–1 usually precludes epidural or subarachnoid anaesthesia

Performance of Subarachnoid Block

Positioning the Patient

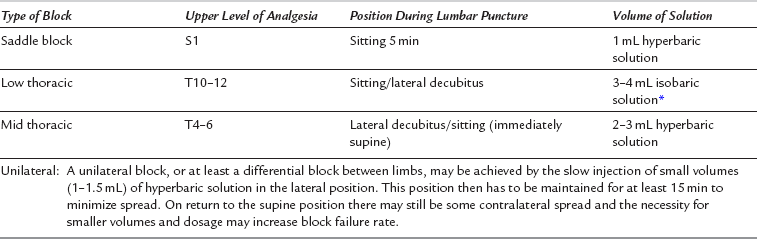

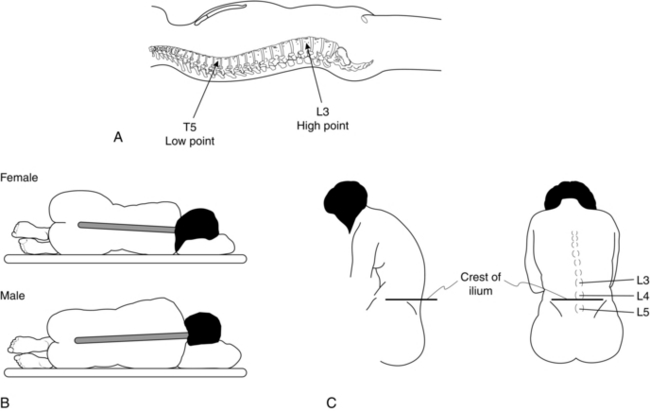

Lumbar puncture for SAB may be performed with the patient sitting or in the lateral decubitus position (Table 24.1, Fig. 24.3). If it is anticipated that lumbar puncture may be difficult, the midline is usually more discernible with the patient in the sitting position, but the risk of hypotension in the sedated patient or following development of the block is increased. The technique of lumbar puncture for the patient in the lateral position is described in the next section.

Technique of Lumbar Puncture

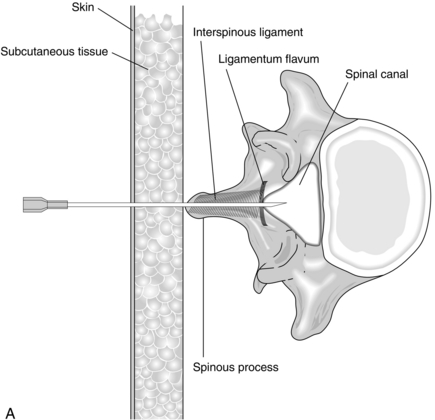

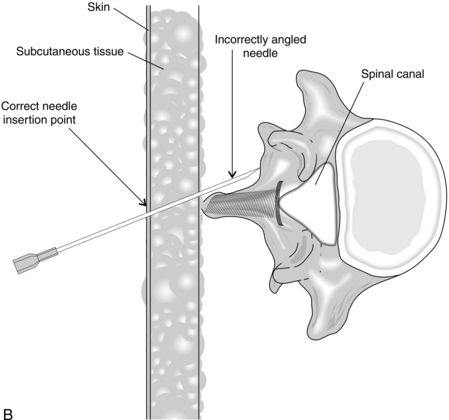

The skin and subcutaneous tissues are infiltrated with local anaesthetic using a small needle. The spinal needle is inserted in the midline, midway between two spinous processes. In the well-positioned patient, the needle is directed at right angles to the skin. Passage through the interspinous ligament and ligamentum flavum into the spinal canal is appreciated easily with a 22-gauge needle (Fig. 24.4A), but these needles are now rarely used because of the high incidence of post-dural puncture headache. With some practice, these structures are usually discernible with a 25G or 27G pencil-point needle, which all anaesthetists should aspire to use. The use of an introducer (19-gauge needle) is advisable to brace the smaller needles, which are very flexible. When the needle tip has entered the spinal canal, the stilette is withdrawn from the needle and the hub is observed for flow of CSF; a needle with a transparent hub makes this easier. A gentle aspiration test should be performed if a free flow of CSF is not observed, or the needle carefully rotated through 90°.

The three most common reasons for difficulty are poor patient positioning, failure to insert the needle in the midline and directing the needle laterally (Fig. 24.4B). This last fault is seen most easily from one side and is usually apparent to onlookers, but not to the anaesthetist, who looks only along the line of the needle.

Factors Affecting Spread

The most important factor which affects the height of block in SAB (Table 24.2) is the baricity of the solution, which may be made hyperbaric (i.e. denser than CSF) by the addition of glucose. The specific gravity (SG) of CSF is 1.004. The addition of glucose 5% or 6% to a local anaesthetic produces a solution with SG of 1.024 or greater. A patient who assumes the sitting position for 5 min after injection of 1 mL of hyperbaric solution develops a saddle block which affects the perineum only. Conversely, a patient placed supine immediately after injection of 2–3 mL develops a block to the mid-thoracic region. Slightly larger volumes are advisable to ensure spread above the lumbar curvature (see Fig. 24.3).

TABLE 24.2

Factors Influencing Spread of Hyperbaric Spinal Solutions

| Factor | Effect |

| Position of patient | Sitting position produces perineal block only, provided that small volumes are used |

| Spinal curvature | With standard volumes (2–3 mL) the block often spreads to T4. With small volumes (1 mL) the block may affect only the perineum even when the patient is placed supine immediately |

| Dose of drug | Within the range of volumes usually employed (2–4 mL), increasing the dose of drug increases the duration of anaesthesia rather than the height of the block |

| Interspace | Minor factor affecting height of block |

| Obesity | Minor factor affecting height of block. Obese patients tend to develop higher blocks |

| Speed of injection | Rapid injection makes the height of block more variable |

| Barbotage | No longer used. Makes the height of block more variable |

Complications

Acute: Hypotension. Significant hypotension is common with SAB and should be anticipated. Changes in position, e.g. turning the patient from the supine to the prone position, may result in a sudden increase in the height of block, with consequent extension of sympathetic blockade. This may occur even after 15–20 min. Treatment (Table 24.3) may not be necessary; moderate hypotension may help to reduce operative blood loss and is tolerated well by most patients. Severe or unwanted hypotension may be treated by i.v. fluids or drugs. The use of large volumes of crystalloid or colloid in this situation is not recommended, as urinary retention may occur postoperatively or circulatory overload may result when the block wears off. However, it is essential that operative blood losses are replaced promptly, and when blood losses are expected (e.g. caesarean section) it is wise to administer fluid in advance of the loss. Hypotension is associated commonly with bradycardia, and ephedrine 5–6 mg i.v. is the most appropriate treatment. Atropine may be useful, but sympathomimetic drugs are usually more effective than vagolytics.

TABLE 24.3

| 5° head-down tilt | |

| Maintain blood volume | |

| Heart rate: | |

| < 60 beats min–1 | Atropine 0.3 mg |

| 60–80 beats min–1 | Ephedrine 3 mg |

| > 80 beats min–1 | Metaraminol 0.5 mg |

Postoperative: Headache. This is more common in young adults and particularly in obstetric patients. It may present up to 2–7 days after lumbar puncture, and may persist for up to 6 weeks. Characteristically it is worse on sitting, occipital in distribution and very disabling. The incidence is reduced by using small-gauge or pencil-point needles and may be reduced by aligning the bevel of the needle to penetrate the dura in a sagittal plane. Simple analgesics may be the only treatment required, but occasionally an epidural blood patch is necessary. The incidence of post-spinal headache is not reduced by keeping the patient supine for 24 h; the patient should remain supine only until the anaesthetic has worn off and the risk of postural hypotension is minimal. If headache is severe and persistent, an epidural blood patch may be performed by removing 20 mL of the patient’s own blood under aseptic conditions and injecting it epidurally at the same interspace as SAB was performed. Injection should be stopped if discomfort is experienced. This is 70–80% effective for lumbar puncture headache and appears to be remarkably free from adverse effects.

Other complications: These include:

Urinary retention – this may be associated with the surgical procedure. Large volumes of i.v. fluids may increase the frequency of this complication.

Urinary retention – this may be associated with the surgical procedure. Large volumes of i.v. fluids may increase the frequency of this complication.

Cranial nerve palsy – sixth nerve palsy may occur and is usually temporary. This complication is more common with larger needles.

Cranial nerve palsy – sixth nerve palsy may occur and is usually temporary. This complication is more common with larger needles.

Spinal cord trauma caused by inserting the needle at too high an interspace – fortunately these conditions, giving rise to permanent neurological damage or paraplegia, are rare.

Spinal cord trauma caused by inserting the needle at too high an interspace – fortunately these conditions, giving rise to permanent neurological damage or paraplegia, are rare.

Continuous Spinal Anaesthesia

Subarachnoid blockade can be produced incrementally or the duration prolonged by using an indwelling spinal catheter. It may be performed using either a small catheter passed through a 19-gauge Tuohy needle or using a purpose-made catheter-over-wire kit such as the Spinocath (see Fig 24.1A). With the latter, the epidural space is located using a loss of resistance technique with a Crawford-type epidural needle and the 22-gauge Spinocath with guide wire, inserted through it to puncture the dura. The guide wire is then withdrawn, leaving the catheter in the subarachnoid space. Therefore there is minimal CSF leak around the catheter, reducing the risk of post-dural-puncture headache.

Performance of Epidural Block

The major differences between SAB and epidural block are summarized in Table 24.4. Further expansion of the technique has taken place with the advent of epidural administration of opioids and other agents such as clonidine or ketamine may have a place in providing postoperative epidural analgesia.

TABLE 24.4

Differences between Subarachnoid and Epidural Block

| Subarachnoid | Epidural | |

| Dose of drug used | Small: minimal risk of systemic toxicity | Large: possibility of systemic toxicity after intravascular injection or total spinal blockade after subarachnoid injection |

| Rate of onset | Fast: 2–5 min for initial effect, 20 min for maximum effect | Slow: 5–15 min for initial effect, 30–45 min for maximum effect |

| Intensity of block | Usually complete anaesthesia | Often not complete anaesthesia for all segments |

| Pattern of block | May be dermatomal for first few minutes, but rapidly develops appearance of cord transection | Dermatomal |

| Addition of vasoconstrictor | Reliably prolongs block with tetracaine, but not with other drugs | Reliably prolongs block with lidocaine. May prolong block with bupivacaine, but not in all patients |

Equipment

Epidural anaesthesia is usually performed using a Tuohy needle (Fig. 24.5). The needle is marked at 1 cm intervals and has a Huber point which allows a catheter to be directed along the long axis of the epidural space. Disposable catheters are available with a single end-hole or with a sealed tip and three side-holes distally.

Technique

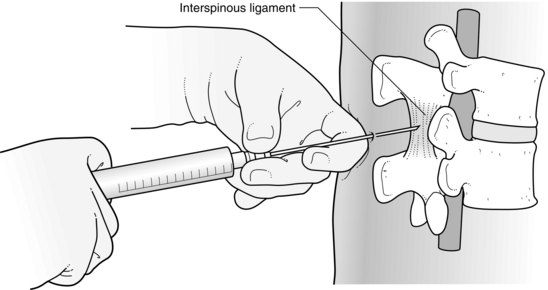

The patient is positioned as for SAB and the vertebral level is identified from the iliac crests. The skin and subcutaneous tissues of the third lumbar interspace are infiltrated with local anaesthetic solution in the midline. A sharp needle is used to puncture the skin and the round-ended epidural Tuohy needle is introduced through the skin puncture, subcutaneous tissue and supraspinous ligament. The common reasons for difficulty are the same as those for SAB. When inserted into the interspinous ligament, the unsupported needle remains steady. The stilette is withdrawn and a 10 mL plastic syringe filled with saline is attached and advanced using firm but gentle pressure on the plunger. The needle must be gripped tightly at all times (Fig. 24.6) to prevent sudden forward movement. When the needle penetrates the ligamentum flavum, there is a sudden loss of resistance to pressure on the plunger, but the needle must not be allowed to advance further. The needle must not be rotated after its tip has entered the epidural space, as this increases the risk of penetration of the dura.

Agents

Lidocaine: Lidocaine is used in concentrations of 1.5–2% with or without adrenaline 1:200 000. Without adrenaline, the duration of action is approximately 1 h; a duration of approximately 1–2.5 h may be expected when solutions containing adrenaline are used, depending on surgical site.

Bupivacaine: Bupivacaine is available in concentrations of 0.25% and 0.5%. Increasing the concentration to 0.75% results in a faster onset, a denser block, more profound motor block (and therefore muscle relaxation) and increased duration of anaesthesia, but this concentration is not now freely available for use in the UK.

Levobupivacaine: Levobupivacaine is the pure S-isomer of bupivacaine and is less cardiotoxic than the racemic mixture, but otherwise appears equipotent in terms of sensory and motor blockade. Levobupivacaine is available as a 0.25%, 0.5% and 0.75% solution. The advantages of a 0.75% solution as described above may be broadly applicable to the use of levobupivacaine although clinical and research experience is more limited. A block lasting more than 4 h may be achieved with a 0.75% solution.

Complications

Intraoperative: Dural tap. The incidence should be less than 0.5% in experienced hands. It usually occurs with the needle rather than the catheter and is immediately obvious because of the free flow of CSF. If this occurs, epidural block should be instituted at an adjacent space and managed cautiously, although experienced anaesthetists, particularly in the obstetric environment, may choose to pass the ‘epidural’ catheter into the subarachnoid space and manage as a continuous SAB (see Ch 35). Puncture of the dura with a large epidural needle leads to a high incidence of headache, of up to 70%. Simple analgesics and adequate hydration may suffice if headache occurs; if not, an epidural blood patch should be performed. Accidental total spinal anaesthesia (see below) is rare because the dural tap is usually obvious.

Total Spinal Anaesthesia: This may occur if the large volume of solution used for epidural anaesthesia is injected into the subarachnoid space. The consequences may be:

Massive Epidural Block and Subdural Block: A very high block may occur in the absence of subarachnoid injection. This may be associated with Horner’s syndrome.

Epidural haematoma. The spinal canal acts as a rigid box, and an expanding haematoma within the canal compresses the spinal cord, resulting in loss of neurological function unless the compression is relieved surgically at a very early stage. Decompression within 6 h is completely effective in virtually all patients, but after 12 h it is almost totally ineffective.

Epidural haematoma. The spinal canal acts as a rigid box, and an expanding haematoma within the canal compresses the spinal cord, resulting in loss of neurological function unless the compression is relieved surgically at a very early stage. Decompression within 6 h is completely effective in virtually all patients, but after 12 h it is almost totally ineffective.

Other neurological complications, e.g. damage to a single nerve root or paraplegia following accidental administration of potassium chloride.

Other neurological complications, e.g. damage to a single nerve root or paraplegia following accidental administration of potassium chloride.

Anticoagulants and Subarachnoid Block or Epidural Anaesthesia

Heparin

Guidelines for the use of low-molecular-weight heparin and epidural anaesthesia are given in Table 24.5.

TABLE 24.5

Guidelines for the Insertion and Removal of Epidural Catheters in Association with Low-Molecular-Weight Heparins (LMWH)

| 1 | Patients who need DVT prophylaxis before theatre should receive LMWH the day before at approximately 18.00 h. |

| 2 | LMWH should not be given on the day of surgery – this allows 12 h before catheter placement; although the LMWH is providing DVT prophylaxis at this time, plasma concentrations are below peak activity and therefore less likely to create a problem. |

| 3 | LMWH may be given 2 h after placement of an epidural catheter. |

| 4 | The epidural catheter should be removed 12 h after the last dose of LMWH and the next dose should not be given until 2 h have elapsed. |

| 5 | Antiplatelet drugs and anticoagulant drugs should not be used concurrently with LMWH. |

| 6 | The smallest effective dose of LMWH should be used. |

| 7 | Patients should have regular (every 4 h) neurological examination after removal of the epidural catheter. This should include sensation, power and reflexes. |

| 8 | In cases of traumatic or repeated epidural puncture, administration of LMWH should be delayed for more than 24 h; an alternative method of DVT prophylaxis should be used. |

| 9 | Epidural mixtures should contain a low concentration of local anaesthetic so that motor function may be assessed. |

| 10 | If the patient develops a neurological abnormality either during epidural infusion or within 48 h of epidural catheter removal, an urgent MRI scan is required and a neurosurgical opinion should be obtained. |

Caudal Anaesthesia

Method

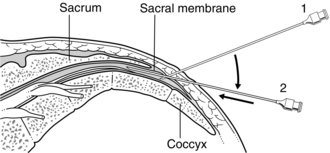

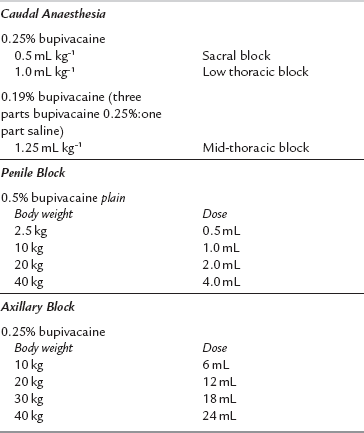

Caudal blockade may be performed with the patient in the prone position, but the left lateral position is usually more acceptable to the patient and easier in the anaesthetized paediatric patient. Palpation down the sacral spine leads to the depression of the sacral hiatus at S5, flanked by the sacral cornua, through which the needle is inserted. A 21-gauge hypodermic needle or 22-gauge cannula is introduced through skin and sacrococcygeal ligament in a cephalad direction at 45° to the skin (Fig. 24.7). When the membrane is penetrated, injection may be performed or the needle hub may be depressed toward the natal cleft, and inserted a further 2–3 mm along the sacral canal; it must be remembered that the dura may extend to S3. Lidocaine 2%, with or without adrenaline, and bupivacaine 0.5% are suitable agents. In an adult, 10 mL of solution blocks anal sensation consistently.

PERIPHERAL BLOCKS

Superficial cervical plexus block is now commonly used for carrying out awake carotid endarterectomy but other specialized blocks are mostly used in ophthalmic and plastic surgery. Only the technique of local anaesthesia for awake intubation is described here. Blocks used in ophthalmic surgery are discussed in Chapter 30.

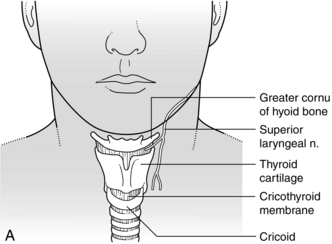

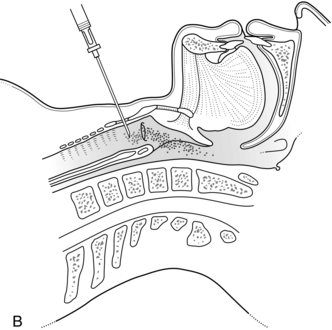

Awake Intubation

The nose is prepared with topical lidocaine 2% with or without a vasoconstrictor such as phenylephrine. The patient may then either suck a benzocaine lozenge, or the posterior tongue and pharynx are sprayed with lidocaine 4%. For laryngeal analgesia, either a ‘spray as you go’ technique through the scope under direct vision is used, or a cricothyroid injection is performed through either a 23-gauge needle or 22-gauge cannula inserted through the cricothyroid membrane (Fig. 24.8A, B) with air aspirated to confirm the position. Two millilitres of lidocaine 4% are injected and the needle is withdrawn immediately. A vigorous cough results and spreads the solution. Although absorption of lidocaine from mucous membranes is rapid, in practice, significant amounts tend to be lost or swallowed and rarely cause systemic toxicity.

Upper Limb Blocks

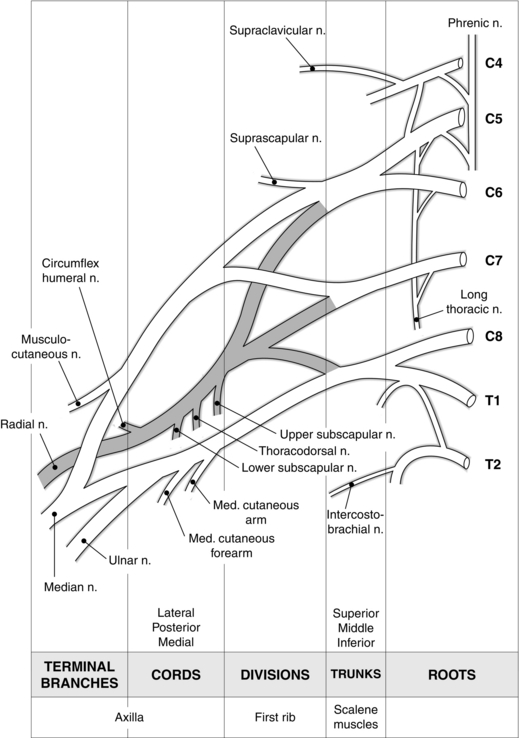

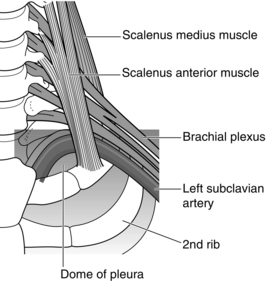

Anatomy of the Brachial Plexus

A sound anatomical knowledge is essential to the practice of peripheral regional anaesthesia. The nerve supply of the upper limb is derived mainly from the brachial plexus, which is formed from the anterior primary rami of the fifth to eighth cervical and first thoracic nerve roots. The roots of the plexus divide repeatedly and recombine to form trunks, divisions, cords and terminal nerves (Fig. 24.9). The roots emerge from the intervertebral foramina and combine into three trunks above the first rib. Each trunk separates above the clavicle into anterior and posterior divisions; anterior divisions supply the flexor structures of the arm and posterior divisions the extensor structures. The divisions recombine into three cords, which surround the second part of the axillary artery behind pectoralis minor and then form the terminal nerves.

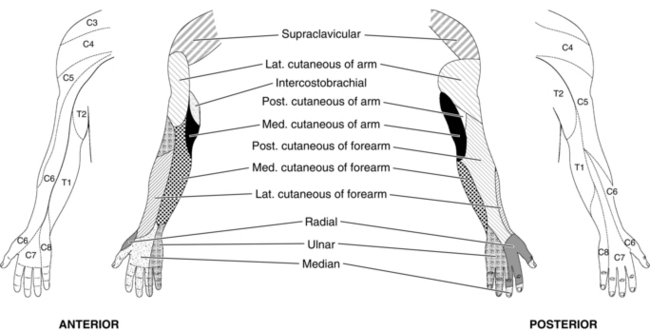

The roots lie between the anterior and middle scalene muscles and are invested in a sheath, derived from the prevertebral fascia, which splits to enclose the scalene muscles. The cutaneous and deep nerve supplies of the upper limb are depicted in Figure 24.10.

Ultrasound-Guidance

Ultrasound-guidance has been greatly increasing in popularity over the last 10 years, particularly for the performance of peripheral upper and lower limb blocks. For the first time, the anaesthetist has been able to visualize anatomical structures and variants, allowing accurate needle placement and importantly, visualization of local anaesthetic spread around these target structures. Potential advantages of these techniques remain a source of debate (Table 24.6). Although definitive outcome studies comparing ultrasound-guidance with nerve stimulation are not available, there is increasing evidence that ultrasound offers a number of advantages including greater block success, faster onset time, reduced procedure-related pain, reduced local anaesthetic dosage and reduced adverse effects such as inadvertent intravascular injection and phrenic nerve paresis with interscalene block.

TABLE 24.6

Potential Advantages of Ultrasound-Guided Nerve Blockade

Visualization of target structure

Visualization of surrounding anatomical structures

Accuracy of needle placement

Visualization of local anaesthetic spread in real time

Compensation for anatomical variation

Avoidance of intraneural or intravascular injection

Variety of approaches (not landmark dependent)

Rapid block onset

Reduced local anaesthetic dosage

Reduced procedure-related pain

Reduced complications

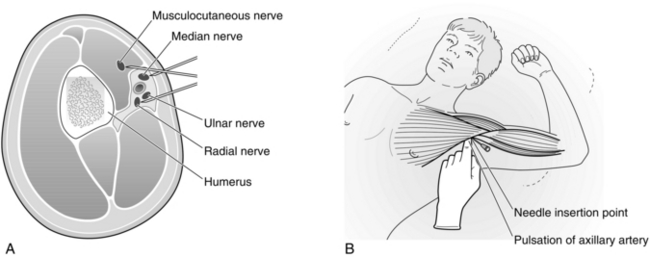

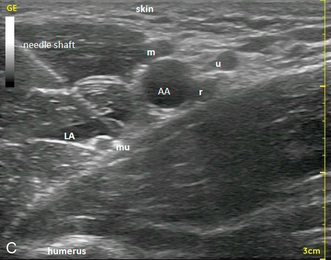

Axillary Block

This technique represents perhaps the safest approach to the brachial plexus for the trainee to learn whether using peripheral nerve stimulation or ultrasound-guidance. It is useful for elbow, forearm and hand surgery and safe for out-patients, but traditional single-injection approaches are limited by high failure rates of both musculocutaneous and radial nerves. This is due to the anatomical positions of the nerves and the presence, in some individuals, of fibrous septae within the brachial plexus sheath which prevent circumferential spread of local anaesthetic. The most common orientation of nerves around the axillary artery is shown in Figure 24.11A, as are the needle positions necessary for successful complete blockade using nerve stimulation. Ultrasound visualization allows both the detection of anatomical variation and the optimization of local anaesthetic spread around these structures. Dense, complete blockade can often be achieved within 10–15 min using multiple injection techniques.

FIGURE 24.11 (A) Cross-sectional relationship of the brachial plexus nerves to the axillary artery. (B) Correct position and approach for axillary block. (C) Ultrasound image of distal axilla showing echogenic needle targeting the musculocutaneous nerve (mu). AA, axillary artery; m, median nerve; u, ulnar nerve; r, radial nerve; LA, local anaesthetic.

Positioning: The patient lies supine with the arm to be blocked abducted to no more than 90° and the elbow bent to 90° (see Fig. 24.11B). Further abduction with the hand placed behind the head is convenient, but the axillary vessels become stretched and distorted, and performance of the block is more difficult.

Method: The axillary artery is palpated and traced to a point 1–2 cm distal to the lateral border of pectoralis major. A 2 mL subcutaneous wheal of local anaesthetic is raised superficial and inferior to the artery at this point, which also blocks the intercostobrachial nerve. A 22-gauge insulated short-bevelled needle is introduced through this wheal after puncturing the skin with a standard needle. The nerve stimulator is set to deliver a current of 2 mA and the needle directed immediately above the artery (almost parallel to the floor). Stimulation of the musculocutaneous nerve causes biceps contraction and flexion of the elbow. The current should then be reduced until optimal contraction is obtained at a current of around 0.5 mA; 5 mL of the LA is injected following gentle aspiration. The needle is then withdrawn and redirected through the same puncture, in a more inferior direction with the current again set to deliver 2 mA. Flexion of wrist and fingers occurs following a distinct fascial click as the needle enters the sheath and stimulates the median nerve. Current is again reduced to optimize muscle contraction at 0.5 mA and 15 mL of LA solution injected in 5 mL increments, each preceded by careful aspiration. Finally, the needle is withdrawn and redirected below the artery until extension of the fingers is obtained and again current reduced from 2 mA to 0.5 mA. Ten mL of LA is then injected in two 5 mL increments. A total of 30 mL of local anaesthetic solution is therefore used. For most routine upper limb surgery, lidocaine 1.5% with adrenaline 1:200 000 is used, but for major painful procedures, ropivacaine or levobupivacaine 0.5% may be substituted. After completion of injection, the arm should be returned to the patient’s side.

Ultrasound-guidance: The plexus of most individuals can be visualized using a linear 10 MHz probe set to a depth of 3 cm. An anatomical survey is carried out to demonstrate the positions of the nerves (Fig 24.11C). The musculocutaneous nerve is generally seen lying between biceps and coracobrachialis muscles lateral to the artery, the median nerve is usually located adjacent to the artery in the ‘9–12 o’clock’ position with the ulnar nerve often seen in the corresponding ‘12–2 o’clock’ position, a discrete distance from the artery and often just below the axillary vein. The radial nerve is the most difficult to visualize and tends to lie beneath the ulnar nerve in the ‘5 o’clock’ position. The block needle is introduced either in-plane or out of plane, following local anaesthetic infiltration. Local anaesthetic is then distributed around the individual nerves as described above and additionally around the ulnar nerve.

Disadvantages: Access is occasionally problematic if arm abduction and external rotation are limited by either additional shoulder trauma or severe arthritis. This approach rarely blocks the axillary nerve unless large volumes of solution are used. If blockade of this nerve is required, a more proximal approach to the plexus should be considered. Puncture of the axillary artery is rarely a problem, but may lead to haematoma formation or inadvertent intravascular injection. Nerve damage occurs rarely and is more likely to result from malposition of the anaesthetized limb or failure to recognize a compartment syndrome postoperatively.

Infraclavicular Block

Advantages: The block can be performed with the arm at the side and may therefore be useful when access for axillary block is prevented by limitation of shoulder abduction. Using ultrasonic location and ensuring local anaesthetic spread posterior and medial to the axillary artery, excellent efficacy and complete block within 10–15 min can be achieved from a single injection site. For best images and ease of needle placement in the limited space below the clavicle, a small curved array probe is used. This probe not only shows the important vascular structures with which the nerves are intimately related, but with experience also demonstrates the three neural cords and the local anaesthetic spread around them. The approach is useful for elbow, forearm and hand surgery and is particularly useful if a catheter is sited for postoperative use, because of greater ease of secure fixation below the clavicle. Blockade of the phrenic nerve is unlikely with the lateral approach.

Disadvantages: Pneumothorax has been reported although the risk appears to be low. Vascular puncture is fairly common using nerve stimulator techniques because of the close proximity of nerves to both axillary artery and vein in this location. Ultrasonic location reduces this to a minimum. Success rates decrease with inadequate spread, but administering 35–40 mL rather than 30 mL of LA solution may improve medial spread with a single-injection approach, providing this remains within the safe recommended dosage of the local anaesthetic agent.

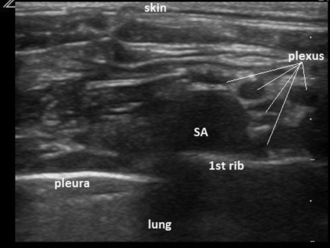

Supraclavicular Block

The key to successful and safe nerve stimulation approaches is accurate palpation of the interscalene groove (see Fig. 24.12) above the clavicle, which helps delineate the position of the first rib and lateral border of pleura as well as locating the plexus. Popularity has been increasing since the introduction of ultrasound-guidance as plexus, subclavian artery, pleura and first rib are all usually straightforward to visualize (Fig 24.13). The needle is introduced in-plane, in a lateral to medial direction and should be visualized continuously to prevent inadvertent pleural puncture.

Advantages: The arm does not require to be abducted for access and complete upper limb local anaesthesia, including axillary nerve block, is possible from a single injection. Onset time may be as short as 10–15 min and 30 mL of solution is sufficient to produce a dense block in most adults. It is suitable for proximal humeral surgery as well as more distal upper limb surgery.

Disadvantages: The risk of pneumothorax is always present, but is very small (< 0.5%) in experienced hands even when using peripheral nerve stimulation. The safety and success depend on the accurate localization of the interscalene groove which may not always be straightforward, particularly in the obese. Pleural puncture should be preventable using ultrasound-guidance but has been reported. Phrenic nerve paralysis may occur in around one-third of patients, but is usually asymptomatic. Axillary block is the method of choice if there is diminished respiratory reserve. Sympathetic block is relatively common and results in Horner’s syndrome. The technique is still not recommended routinely for out-patients.

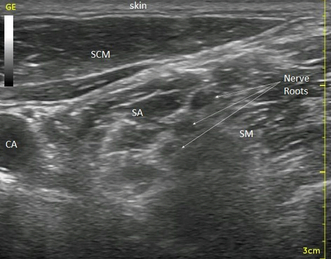

Interscalene Block

Advantages: This is the most proximal approach to the brachial plexus and the only approach which reliably blocks the plexus above C5. With adequate volume (25–30 mL) interscalene injection usually extends to block the cervical plexus roots C3 and C4 and is therefore most suitable for shoulder and upper arm surgery.

Disadvantages: Block of the C8 and T1 roots may prove difficult and make the technique rather less suitable for hand surgery. Complications are similar to those for supraclavicular block but phrenic nerve block occurs almost universally with the volumes of local anaesthetic described. Ultrasound guidance, targeting the C5 and C6 nerve roots (Fig 24.14) allows much smaller volumes of LA (as little as 5–10 mL) to be used for postoperative analgesia, reducing the incidence of phrenic paresis to around 50%. Pneumothorax, vertebral artery puncture, total spinal and direct intraspinal injection are also possibilities. Seizures may occur from direct vertebral artery injection with as little as 1–2 mL of LA solution.

Blocks in the Trunk

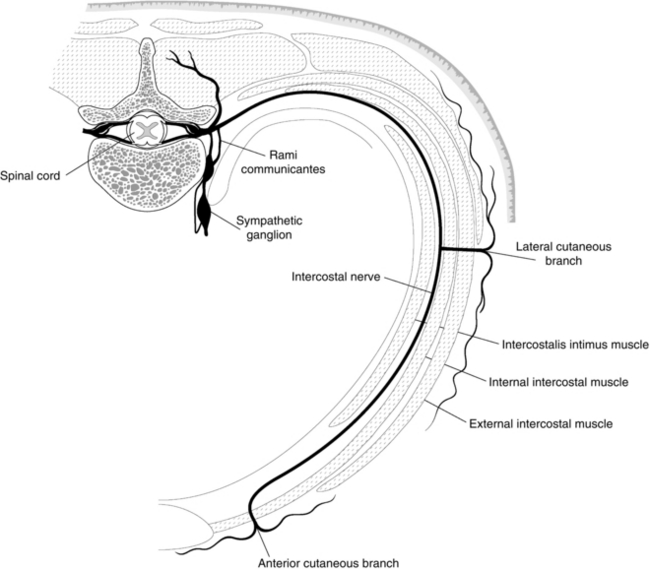

Intercostal Nerve Block

Anatomy: Intercostal nerves are formed from the ventral rami of segmental thoracic nerves after communicating with the associated sympathetic ganglia through white and grey rami communicantes (Fig. 24.15). An intercostal nerve has three main branches: the lateral cutaneous branch divides into anterior and posterior branches; the anterior terminal branch supplies the anterior thorax, rectus muscle and overlying skin; and a collateral branch arises from most nerves in the posterior intercostal space. This may rejoin the main nerve or form a separate anterior cutaneous nerve. Fibres from T1 join the brachial plexus, T2 and T3 supply fibres to form the intercostobrachial nerve, and T12, together with L1, contribute to the iliohypogastric, ilioinguinal and genitofemoral nerves.

Method: The optimal place to block the intercostal nerve is proximal to the formation of the lateral cutaneous branch, posterior to the mid-axillary line. With the patient in the lateral position, nerve blocks may be conveniently performed immediately following surgery for unilateral procedures such as open biliary and gallbladder surgery. In awake patients, for example following unilateral rib fractures, a sitting position with the patient leaning forward to abduct the scapulae is often convenient. A 23-gauge needle is inserted perpendicular to the skin to make contact with an appropriate rib. The needle is then ‘walked’ caudally until it can be inserted under the lower border of the rib, through the external intercostal muscle (a depth of 2–3 mm). Following a negative aspiration test, 3–5 mL of local anaesthetic solution is then injected. Rapid absorption of LA solution may produce high systemic concentrations after multiple intercostal nerve blocks and the dose and concentration of drug need to be chosen carefully; 0.25–0.5% levobupivacaine or ropivacaine 0.2–0.5% is recommended, depending on the number of intercostal nerves being blocked. A single injection of 20 mL using a catheter technique may block up to five adjacent segments (approximately two above and three below). Pneumothorax and haemorrhage are the most likely complications after intercostal nerve block.

Lower Limb Blocks

Lower limb blocks are practised less frequently than upper limb blocks for three reasons:

It is not possible to block the whole of the lower limb with one injection.

It is not possible to block the whole of the lower limb with one injection.

Subarachnoid or epidural anaesthesia may prove simpler.

Subarachnoid or epidural anaesthesia may prove simpler.

There is an impression among some anaesthetists that lower limb blocks are difficult and unreliable.

There is an impression among some anaesthetists that lower limb blocks are difficult and unreliable.

Sciatic Nerve Block

Anatomy: The sciatic nerve (L4, L5, S1–3) arises from the sacral plexus, passes through the great sciatic foramen and descends in the posterior thigh to the popliteal fossa, where it divides into the tibial and common peroneal nerves. In the thigh, it supplies muscles and the hip joint. The posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh (S1–3) may run with the sciatic nerve or separate from it proximally; this nerve supplies the skin of the posterior thigh and upper calf. The tibial and common peroneal nerves, together with the saphenous nerve, supply all structures below the knee.

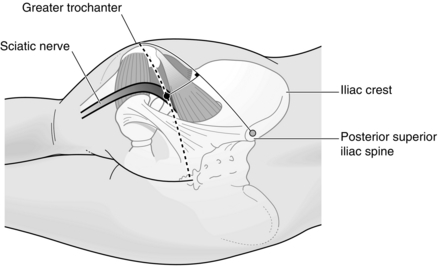

Method: There are several approaches to the sciatic nerve; with ultrasound-guidance the nerve is best visualized where it is most superficial either subgluteal or in the popliteal fossa (Fig. 24.16) With nerve stimulation, the posterior approach described by Labat is the most straightforward but requires the patient to be turned to a lateral semi-prone position; the limb to be blocked is uppermost and flexed at the knee. A line is drawn from the posterior superior iliac spine to the tip of the greater trochanter of femur. At the midpoint, a second perpendicular line is drawn caudally for 4–5 cm to mark the point of needle insertion (Fig. 24.17). Following aseptic preparation, the skin is infiltrated with 2 mL of local anaesthetic and a 100 mm, 21G insulated block needle inserted perpendicular to skin with the stimulator set to deliver 2 mA. After some initial twitches in the gluteal area, further advancement usually results in hamstring contraction. The current is then best reduced to 0.5–1 mA before further subtle advancement produces either dorsiflexion or, ideally, plantar flexion of the foot at a current of 0.5 mA. Fifteen to 20 mL of local anaesthetic is then injected in 5 mL aliquots after negative aspiration.

FIGURE 24.16 Ultrasound image of sciatic nerve surrounded by local anaesthetic (LA), in the popliteal fossa.

Femoral Nerve Block

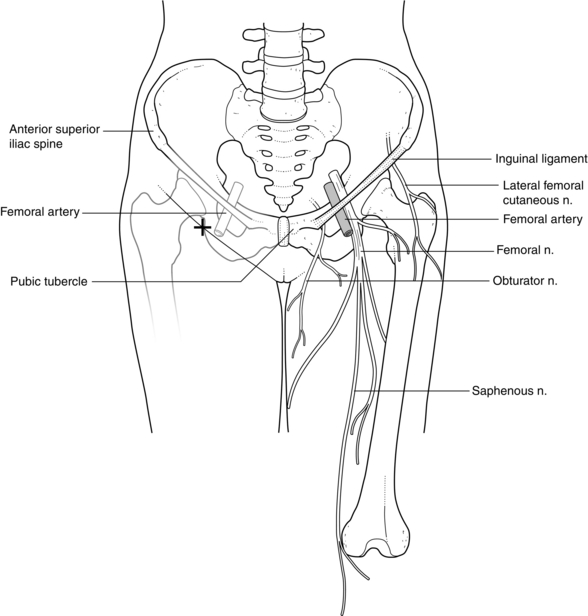

Anatomy: The femoral nerve (L2–4) arises from the lumbar plexus and runs between psoas and iliacus to enter the thigh beneath the inguinal ligament, 1–2 cm lateral to the femoral artery and at a slightly greater depth. Branches of the anterior division include the intermediate and medial cutaneous nerves of the thigh and the supply to the sartorius. The posterior division supplies the quadriceps and the hip and knee joints and terminates as the saphenous nerve, which supplies the skin of the medial side of the calf as far as the medial malleolus and sometimes the medial side of the dorsum of the foot.

Method: The patient lies supine and the inguinal ligament and femoral artery are identified. The skin is anaesthetized lateral to the femoral artery, 1 cm below the inguinal ligament. A 22-gauge, short-bevelled insulated needle is inserted parallel to the artery in a cephalad direction of approximately 45° with respect to skin (Fig. 24.18). With the nerve stimulator set to deliver 2 mA, two distinct fascial pops are generally appreciated before muscle contractions occur. Patellar ascension or ‘tapping’ is observed when the femoral nerve is accurately located with the current reduced to around 0.5 mA. Observation of this patellar movement should prevent confusion with the contractions obtained by direct stimulation of the sartorius muscle. Fifteen to 20 mL of solution is required for satisfactory blockade. Ultrasound-guidance, either in-plane or out of plane, can be used to locate the nerve and confirm spread of local anaesthetic around it and below the fascia iliaca.

Suitable LA agents for femoral or ‘3-in-1’ block are the same as for sciatic nerve block.

Lumbar Plexus Block

Anatomy: The lumbar plexus is formed from the ventral rami of the first three and large part of the fourth lumbar nerves. The nerves run from the vertebral column in an inferolateral direction within the posterior part of the psoas muscle. The femoral and lateral cutaneous nerves then emerge from the lateral aspect and the obturator from the medial aspect of this muscle and all three nerves may be blocked with LA within the psoas muscle at the L3/4 level or L4/5 level.

Method: The patient is positioned either sitting or more commonly in the lateral decubitus position with operative side uppermost. The spine of the fourth lumbar vertebra is identified by palpating the iliac crests. A 21-gauge,100-mm insulated needle is inserted at the junction of the lateral third and medial two thirds of a line drawn between the spinous process of L4 (approximately 1 cm cephalad to the upper edge of the iliac crests) and a perpendicular line, parallel to the spinal column passing through the posterior superior iliac spine. After contact with the lumbar transverse process is made, the needle is withdrawn and redirected in a cephalad direction (or occasionally in a caudad direction) until the needle glides over the transverse process. The depth from skin is variable but contact with the plexus, resulting in quadriceps contraction, is usually found at a depth of 1.5–2 cm from the transverse process. Following careful aspiration, 15–20 mL of local anaesthetic, usually levobupivacaine 0.375–0.5% or ropivacaine 0.4–0.5%, is injected in 5 mL increments.

Complications: Care must be taken in selecting an appropriate concentration of LA, particularly when combined with sciatic block, to ensure maximum dosage is not exceeded, resulting in systemic toxicity. Epidural spread, usually unilateral, has been reported particularly in paediatric practice. Penetration of the retroperitoneum leading to haematoma formation, kidney or bowel puncture is possible. Central nervous system toxicity, epidural and intrathecal spread leading to respiratory failure and cardiac arrest have all been reported.

Ankle Block

Anatomy: Five nerves supply the forefoot. The medial and lateral plantar nerves are the terminal branches of the posterior tibial nerve, which enters the foot posterior to the medial malleolus; they supply deep structures within the foot and all of the sole. The common peroneal nerve divides into deep and superficial branches; the deep peroneal nerve supplies the web space between first and second toes and the superficial branch supplies the dorsum of the foot. The saphenous nerve may supply a variable area of skin on the medial side of the dorsum of the foot. The sural nerve is a branch of the tibial nerve; it runs posterior to the lateral malleolus and supplies skin over the lateral side of the foot and 5th toe.

Method: To block the posterior tibial nerve, the posterior tibial artery is palpated behind the medial malleolus as far distally as possible. Injection of 3 mL of LA to each side of it, below deep fascia, blocks medial and lateral plantar nerves. Alternatively, the posterior tibial nerve may be blocked with 5 mL of local anaesthetic injected at a point distal and posterior to the sustentaculum tali, particularly when there is no vascular landmark. Injection of 2 mL of LA to each side of the dorsalis pedis artery, below deep fascia, blocks the deep peroneal nerve. The saphenous and superficial peroneal nerves are blocked by s.c. infiltration at the level of the ankle joint in a line extending from a point anterior to the medial malleolus to the lateral malleolus. The sural nerve is blocked with a subcutaneous infiltration behind the lateral malleolus. A complete block of the foot requires 15 mL of solution; ropivacaine, levobupivacaine or racemic bupivacaine are most suitable for postoperative analgesia. It is probably advisable to avoid all five nerve blocks when the circulation to the foot is impaired although selective blockade is useful for vascular amputations. A single injection sciatic block is often therefore more appropriate as the sole technique for significant foot surgery.

Continuous Peripheral Nerve Block

These techniques are growing in popularity for both upper and lower limb blocks, as a method of prolonging postoperative analgesia and facilitating rehabilitation without the side-effects associated with opioids and with fewer unwanted cardiorespiratory complications and the urinary difficulties associated with epidural analgesia. Postoperative care is simplified and may usually be carried out in a general ward environment. The anaesthetist should be proficient in single-shot peripheral blocks – brachial plexus, femoral, lumbar plexus and sciatic – before advancing to catheter techniques. Some of the most popular techniques would include continuous femoral infusion following total knee replacement, sciatic infusion following below knee amputation, interscalene infusion following major shoulder surgery and infraclavicular infusions for elbow replacement or arthrolysis. Equipment has improved greatly in recent years and insulated Tuohy needles (see Fig. 24.1) and facet-tipped needles are available to assist catheter placement. Local anaesthetic agents, usually levobupivacaine or ropivacaine, because of their reduced systemic toxicity, are most commonly used in concentrations of 0.1–0.25% although much lower concentrations of levo-bupivacaine have been used by infusion for femoral nerve blockade following total knee arthroplasty in an attempt to minimize motor blockade and promote earlier and safer ambulation. Alternatively, local anaesthetic top-ups can be administered by intermittent bolus either by appropriately trained staff, or as part of a patient-controlled system with or without a background infusion.

SPECIAL SITUATIONS

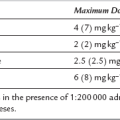

Agents and doses for paediatric blocks are shown in Table 24.7. Caudal block for subumbilical surgery may be prolonged usefully in the postoperative period by the addition of preservative-free S (+)-ketamine 0.5 mg kg–1.

Brull, R., McCartney, C.J.L., Chan, V.W.S., El-Beheiry, H. Neurological complications after regional anesthesia: contemporary estimates of risk. Anesth. Analg. 2007;104:965–974.

Chelly, J.E., Casati, A., Fanelli, G. Continuous peripheral nerve block techniques; an illustrated guide. London: Mosby; 2001.

Cook, T.M., Counsell, D., Wildsmith, J.A. Royal College of Anaesthetists Third National Audit Project 2009. Major complications of central neuraxial block: report on the Third National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists. Br. J. Anaesth. 2009;102:179–190.

Ellis, H., Feldman, S., Harrop Griffiths, W. Anatomy for anaesthetists, eighth ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2004.

Horlocker, T.T., Wedel, D.J., Rowlingson, J.C., et al. Regional anesthesia in the patient receiving antithrombotic or thrombolytic therapy: American Society of Regional Anesthesia and Pain Medicine Evidence-Based Guidelines (3rd edn). Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2010;35:64–101.

Marhofer, P. Ultrasound guidance for nerve blocks: principles and practical implementation. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2008.

Neal, J.M., Gerancher, J.C., Hebl, J.R., et al. Upper extremity regional anesthesia: essentials of our current understanding 2008. Reg. Anesth. Pain Med. 2009;34:134–170.

Rigg, J.R.A., Jamrozik, K., Myles, P.S., MASTER Anaesthesia Trial Study Group. Epidural anaesthesia and analgesia and outcome of major surgery: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1276–1282.

Wildsmith, J.A.W., Armitage, E.N., McClure, J.H. Principles and practice of regional anaesthesia, third ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.