Living-Related Conjunctival–Limbal Allograft (lr-CLAL) Transplantation

Surgical Procedure

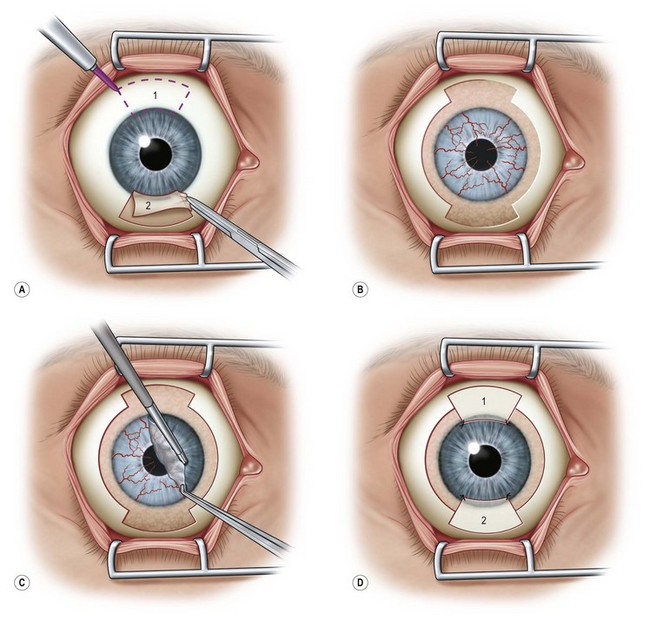

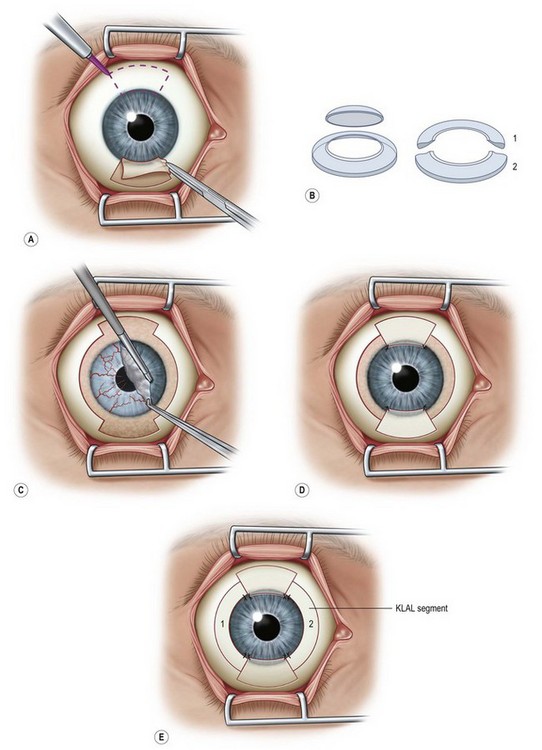

Harvesting the donor tissue is essentially the same as in CLAU. This procedure is typically done under local anesthesia using subconjunctival injection of xylocaine plus epinephrine. In some cases, retrobulbar/peribulbar anesthesia may be necessary. Two 60-degrees arcs of limbal lenticule, each spanning 2–3 clock hours, are harvested from one or both eyes of donor at 12 or 6 o’clock positions. A gentian violet surgical marking pen may be used to mark the conjunctival portions of the grafts (Fig. 41.1). The dissection can be started with lamellar dissection from the corneal side approximately 1 mm anterior and extending 2 mm posterior to the limbus, leaving behind the Tenon’s capsule as much as possible. Alternatively, as the authors prefer, the dissection can be started on the conjunctiva and carried forward towards the limbus about 1–1.5 mm onto the cornea in a superficial manner. Care should be taken to avoid buttonholing of the donor tissue. Dissection onto the peripheral cornea past the palisades of Vogt is critical in order to obtain limbal stem cells. Amputation of the tissue peripheral to this landmark with result in the harvesting of conjunctiva only.

Typically, a 5-mm conjunctival skirt is harvested; however, the amount of the conjunctiva can be increased if the recipient eye also requires symblepharon repair and fornix reconstruction. After excising the donor tissue, the surrounding conjunctiva is undermined and advanced anteriorly and sutured with 10-0 nylon (or dissolvable suture) to close or partially close the conjunctival defect. Although the donor sites heal quickly, closing the defect enhances patient comfort and reduces likelihood of localized pannus formation.1

Recipient Eye

The surgical procedure of lr-CLAL is identical to CLAU.1 Surgery is done under general or retrobulbar/peribulbar anesthesia. After a 360-degree conjunctival peritomy, subconjuntival scar tissues are removed as much as possible, which typically results in the recession of the conjunctival edge to 3–5 mm from the limbus. Hemostasis is achieved with mild wet-field cautery or dilute epinephrine (1 : 10 000). Corneal pannus is removed with special caution not to perforate the cornea. Donor grafts are sutured to the recipient eye at the corresponding anatomic sites by interrupted 10-0 nylon sutures. As an alternative to using sutures, the lr-CLAL grafts can also be directly fibrin glued onto the prepared bed.2,3 This approach has the potential to decrease operative time, increase ease of technique, and improve patient comfort postoperatively. The surgical site may be covered with an overlain amniotic membrane or a high-DK bandage contact lens. At the end of surgery, upper and lower punctal occlusion and lateral tarsorrhaphy may be performed to protect grafts from the mechanical trauma of blinking, as well as from evaporative moisture loss in the early postoperative period in the more severe cases (Fig. 41.2).

Cincinnati Procedure

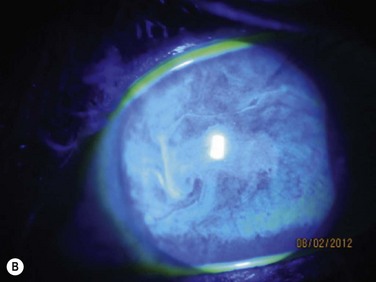

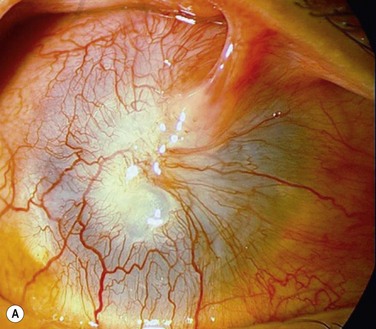

The Cincinnati procedure combines lr-CLAL and KLAL.4 This procedure is considered for patients with both limbal and conjunctival deficiency. The Cincinnati procedure is useful in the management of eyes with cicatrizing conjunctival diseases and total limbal deficiency, such as SJS, OCP, and some chemical injuries. It improves the outcome by adding goblet cells and mucin production to the surface, providing barriers to symblepharon formation, and creating better fornices to allow for a better contact lens fitting, if required. The Cincinnati procedure uses only one corneoscleral rim, which is divided into two 180-degree KLAL segments. The harvested living-related tissue is typically sutured in the 12- and 6-o’clock meridians followed by the cadaveric donor segments which are placed at the 3- and 9-o’clock meridians (Fig. 41.3). The potential disadvantages, compared with KLAL alone are the risks to the donor, the time required to identify and test the donor, and the increased antigen load to the recipient. The advantages of the Cincinnati procedure are the increased amount of stem cells transplanted, the covering of the limbus with donor tissue for 360 degrees and the conjunctival and goblet cells that are provided. This procedure results in improved outcomes on those most challenging patients with severe ocular surface disease – those patients with severe conjunctival deficiency and limbal deficiency (Fig. 41.4).4

Postoperative Management

The systemic immunosuppressive regimen is similar to KLAL and includes mycophenolate mofetil (1–2 g/day) and tacrolimus (4–8 mg/day) in twice a day dosing. The doses are adjusted according to ocular surface inflammation, trough levels and systemic adverse effects in collaboration with a transplant specialist. Oral prednisolone 0.5–1 mg/kg/day is started and tapered down during 6–8 weeks while inflammation decreases. Tapering of tacrolimus is started at 6–12 months based on the level of inflammation. In some patients, with an HLA-matched donor tissue, the taper may be started sooner while in patients with underlying inflammatory diseases it may be necessary to continue indefinitely on a maintenance dose.4,5

Rejection

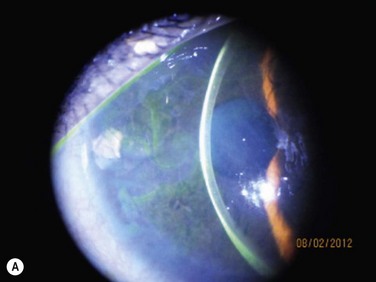

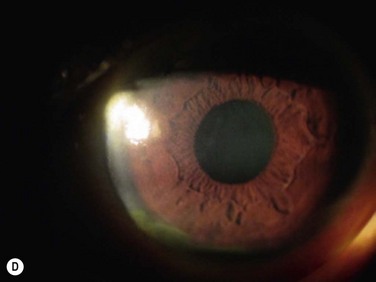

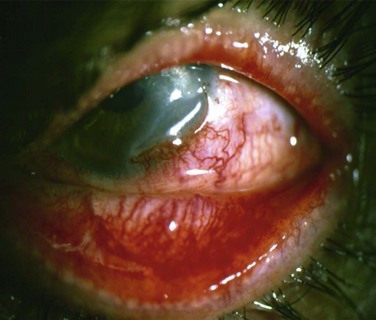

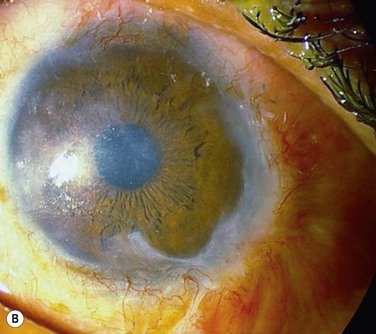

Acute rejection is the most common postoperative complication of lr-CLAL, occurring in 25% to 33% of cases.6 Acute rejection typically presents with conjunctival injection, graft swelling and engorgement, with a progressively moving epithelial rejection line (Fig. 41.5).7–9 Chronic rejection typically presents more insidiously as graft thinning with progressive corneal conjunctivalization/vascularization.

Acute rejections can be treated with an increase in dosage and frequency of topical and systemic steroids. Subconjunctival injection of triamcinolone may also be used. They are tapered according to reduction of ocular surface inflammation, vessel engorgement, local chemosis and disappearance of the epithelial rejection line.5,7 Chronic rejection is treated with an increase in dosage of systemic immunosuppressives medication

There are a few studies that suggest HLA matching may be useful in reducing the risk of rejection in lr-CLAL. In a prospective study of allogeneic conjunctival transplantation in 12 cases of bilateral ocular surface disorders, fewer rejection episodes and a better outcome was seen in patients who underwent identical or haploidentical HLA-matched grafts, compared with non-matched grafts.10 Similar findings were observed in eight patients with severe chemical burns and SJS who underwent lr-CLAL from HLA-matched and unmatched donors. These studies suggest that HLA matching may play a role in graft survival.

Outcomes

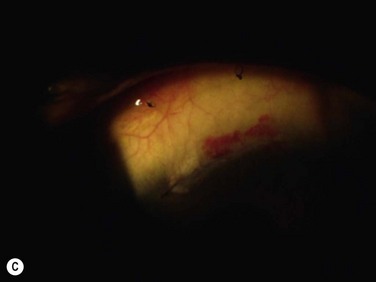

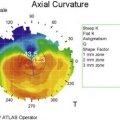

Healing of the corneal epithelial defect and appearance of a smooth transparent epithelial surface are considered clinical success (Fig. 41.6).8 Failure is defined as the presence of abnormally high fluorescein permeability with diffuse late-staining epithelium, recurrence of conjunctivalization, neovascularization, or persistent epithelial defects.11,12

The survival rate of lr-CLAL has been reported between 14% to 91.6%.5,8,10,13,14,15 This wide range in outcomes is due, in part, to differences in inclusion criteria, follow-up periods, immunosuppression regimens, and success criteria. In a study with a mean follow-up of 48.7 months, 1 year after surgery visual acuity improved in 46.2%, and a stable corneal surface was achieved in 84.6% of the eyes. At the final follow-up, 66.6% of the eyes that had gained visual acuity 1 year after surgery maintained an improved visual acuity, and 93.9% still had a stable corneal surface.11 In another study with a mean follow-up of 32 months, the success rate was reportedly as high as 89%.16

Complications

Donor eyes complications in lr-CLAL are rare and donor sites typically recover very well, without complication with re-epithelialization of the peripheral denuded limbus, within several days17. Donor sites may be partially re-epithelialized by conjunctival epithelium with some associated vessels in the periphery; however, this rarely leads to conjunctival growth beyond the excised area. Other possible complications are localized haze, pseudopterygium, filamentary keratitis, microperforation, abnormal epithelium, progressive conjunctivalization, corneal depression and subclinical limbal stem cell deficiency. Closing the conjunctival gap either by advancing the conjunctiva or with amniotic membrane and reducing the postoperative inflammation may reduce the risk of such complications in the donor eye. Excision and transplantation of more than six clock hours is best avoided for fear of precipitating limbal stem cell deficiency in the donor.

Intraoperative complications of the recipient eye include damage to the muscle during symblepharon release, bleeding during superficial keratectomy and corneal perforation. In most situations, putting the limbal tissue at 6 and 12-o’clock positions is important to have a constant coverage by upper and lower lids with a good spreading of tear film. Chronic exposure will lead to thinning, progressive vascularization and final failure of donor lenticules. Donor limbal tissue should be adequately trimmed and thinned. Thee placing of thick limbal grafts presents a barrier for epithelial cells by creating a large the step. It may also result in improper distribution of the tear film with subsequent dellen formation. Applying amniotic membrane may help reduce the step between thick or poorly trimmed limbal tissue and the ocular surface. Limbal alignment is important to prevent exposure and cutting limbal grafts during trephination in probable future keratoplasty. Very small limbal grafts can lead to PED, sectoral conjunctivalization, thinning and perforation. Proper suturing and timely suture removal are necessary to prevent dislodging of the donor tissue by the shearing action of the lids and to avoid injury to the growing epithelial edge.18

References

1. Dua, HS, Miri, A, Dalia, G, et al. Contemporary limbal stem cell transplantation – a review. Clin Exp Ophthalmology. 2010;38:104–117.

2. Nassiri, N, Pandya, HK, Djalilian, AR. Limbal allograft transplantation using fibrin glue. Arch Ophthalmol. 2011;129:218–222.

3. Santos, MS, Gomes, JA, Hofling-Lima, AL, et al. Survival analysis of conjunctival limbal grafts and amniotic membrane transplantation in eyes with total limbal stem cell deficiency. Am J Ophthalmol. 2005;140:223–230.

4. Biber, JM, Skeens, HM, Neff, KD, et al. The Cincinnati procedure: technique and outcomes of combined living-related conjunctival limbal allografts and keratolimbal allografts in severe ocular surface failure. Cornea. 2011;30:765–771.

5. Javadi, MA, Baradaran-Rafii, AR. Living-related conjunctival–limbal allograft for chronic or delayed-onset mustard gas keratopathy. Cornea. 2009;28:51–57.

6. Kwitko, S, Marinho, D, Barcaro, S, et al. Allograft conjunctival transplantation for bilateral ocular surface disorders. Ophthalmology. 1995;102:1020–1025.

7. Daya, SM, Ilari, L. Living related conjunctival limbal allograft for the treatment of stem cell deficiency. Ophthalmology. 2001;108:126–134.

8. Gomes, JAP, Santos, MS, Ventura, AS, et al. Amniotic membrane with living related corneal limbal/conjunctival allograft for ocular surface reconstruction in Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Arch Ophthalmol. 2003;121:1369–1374.

9. Sangwan, VS, Fernandes, M, Bansal, AK, et al. Early results of penetrating keratoplasty following limbal stem cell transplantation. Ind J Ophthalmol. 2005;53:31–35.

10. Rao, SK, Rajagopal, R, Sitalakshmi, G, et al. Limbal allografting from related live donors for corneal surface reconstruction. Ophthalmology. 1999;106:822–828.

11. Reinhard, T, Spelsberg, H, Henke, L, et al. Long-term results of allogeneic penetrating limbo-keratoplasty in total limbal stem cell deficiency. Ophthalmology. 2004;111:775–782.

12. Scocco, C, Kwitko, S, Rymer, S, et al. HLA-matched living-related conjunctival limbal allograft for bilateral ocular surface disorders: long-term results. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2008;71:781–787.

13. Liang, L, Sheha, H, Li, J, et al. Limba Stem cell transplantation: new progresses and challenges. Eye. 2009;23:1946–1953.

14. Wylegala, E, Dobrowolski, D, Tarnawska, D, et al. Limbal stem cells transplantation in the reconstruction of the ocular surface: 6 years experience. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2008;18:886–890.

15. Miri, A, Al-Deiri, B, Dua, HS. Long-term outcomes of autolimbal and allolimbal transplants. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1207–1213.

16. Fernandes, M, Sangwan, VS, Rao, SK, et al. Limbal stem cell transplantation. Ind J Ophthalmol. 2004;52:5–22.

17. Miri, A, Said, DG, Dua, HS. Donor Site Complications in Autolimbal and Living-Related Allolimbal Transplantation. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:1265–1271.

18. Baradaran-Rafii, A, Eslani, M, Jamali, H, et al. postoperative complications of conjunctival limbal autograft surgery. Cornea. 2012;31:893–899.