CHAPTER 9 Liver resection (left lateral sectionectomy)

Step 1. Surgical anatomy

♦ Laparoscopic removal of the left lateral section of the liver can be very straightforward. For most surgeons, this will be their first “major” liver resection. However, there is still a real risk of disaster. Because of this combination of an easy procedure and intraoperative complications that are potentially life threatening, it is imperative that the surgeon understands the anatomy and instrumentation. Skill and experience with both open liver surgery and advanced laparoscopy remain essential.

♦ The left lateral section of the liver (formerly called the left lobe, now segments 2 and 3) is defined as the parenchyma to the left side of the falciform ligament. This ligament fans out over the surface of the left lateral section as Glissons capsule and condenses posteriorly as the left triangular ligament, attaching the liver to the undersurface of the diaphragm.

♦ The round ligament, or ligamentum teres, representing the usually obliterated umbilical vein, runs in the free edge of the falciform ligament, and enters the liver anterior to a variably thick bridge of liver tissue linking segments 3 and 4b. The caudate lobe lies posteriorly, separated from the left lateral section by the hepatogastric ligament or lesser omentum.

♦ The branching inflow to the left hemiliver lies just deep to the entry of the round ligament into the liver. Here the left portal triad of hepatic artery, bile duct, and portal vein divides with branching to segments 2 and 3 on the left and segment 4 on the right.

♦ The left lateral section is drained by the left hepatic vein, which usually joins with the middle vein before entering the vena cava. The left vein has a variable extrahepatic course, but its left side can be exposed by mobilizing the left lateral section.

Step 2. Preoperative considerations

Patient preparation

♦ Liver resection should always be undertaken for a valid reason, whether open or laparoscopic.

♦ Tumors are removed because of known malignancy, uncertain diagnosis, or symptoms.

♦ Tumors must lie well clear of the line of transection (i.e., the line of the falciform ligament).

♦ Good preoperative imaging with multiphase computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is essential. This is the one liver operation where intraoperative ultrasound is not always essential, because of the clear sectional definition by the falciform ligament.

♦ Resection will be much easier in a healthy, slim, nonsteatotic liver.

♦ Enlarged fatty livers can be greatly improved by placing the patient on a high-protein, very low calorie diet for 2 weeks.

♦ The surgeon must understand the principles of open liver surgery and have skills in advanced laparoscopic surgery, such as suturing.

Step 3. Operative steps

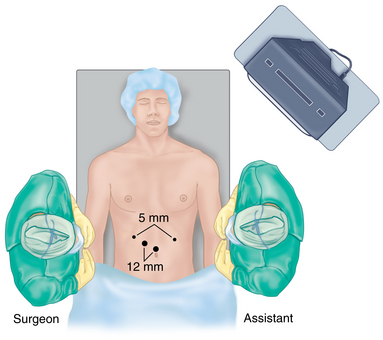

Access and port placement

♦ Access is via the umbilicus with a 12-mm Hassan canula, or elsewhere in the upper abdomen if adhesions are expected. Carbon dioxide is insufflated to the lowest pressure permitting visualization (because of risk of embolization).

♦ Two to three working ports are needed. One of these needs to be a 12 mm size for linear stapler access. With experience, only two 5-mm ports are needed and a 5-mm, 30-degree laparoscope is used. It is best if the large port traverses the umbilicus.

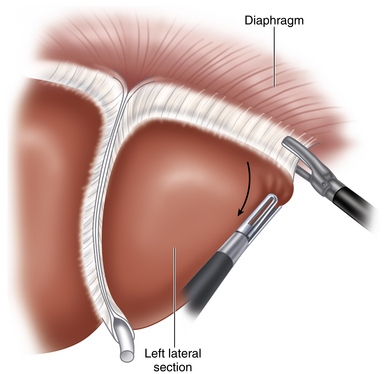

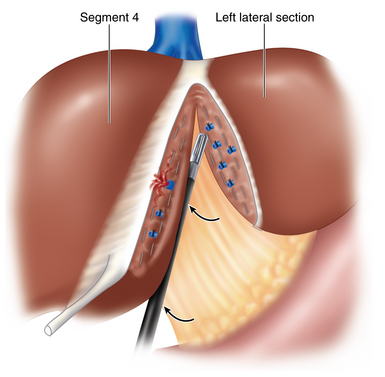

♦ The left lateral section is mobilized by dividing the left triangular ligament, watching for the gastroesophageal junction posteriorly and the pericardium anteriorly. The left phrenic vein will be seen entering the left hepatic vein (Figure 9-2).

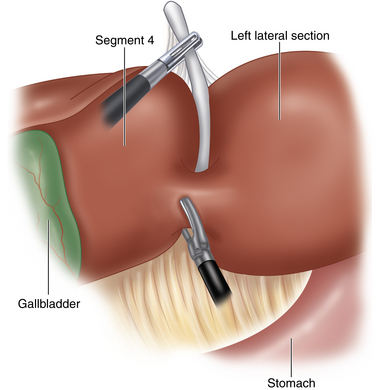

♦ The bridge of liver tissue overlying the round ligament is divided, and the left lateral section is lifted by placing a grasper or sucker beneath and medial, to feel the potential vascular control that can be achieved by such a maneuver.

♦ The round ligament can be preserved or divided to allow best access to the line of transection, usually just to the left of the falciform ligament (Figure 9-3).

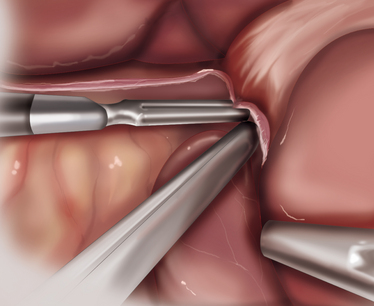

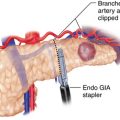

♦ Liver transection can be performed with a variety of instruments, just as in open surgery. The simplest and quickest technique is to use a linear cutting stapler such as the Endo-GIA (Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts). My preference is for a 60-mm vascular (2.0 white) load with articulation.

♦ Correct stapler technique means taking the liver in layers in almost all instances. Two or three layers of staple firings are needed, using up to nine loads. The trick is to take no more than 15 mm of liver thickness in one bite, with the thin arm of the stapler gently insinuated into the liver substance until resistance (usually a vessel) is felt.

♦ If the patient is very slim, as may be the case in thin females, then it may be possible to take the whole left lateral section in two or three firings. Glisson’s capsule pinches down on itself giving a reassuring hemostatic seal (Figure 9-4).

♦ Particularly on the less vascular anterior half of the resection, other devices, such as laparoscopic bipolar shears, Ligasure (Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts), or ultrasonic coagulating shears, Harmonic (Ethicon, Somerville, New Jersey) shears, can be used.

♦ When using the LigaSure, first you crush the parenchyma as with “Kelly clysis” in open liver surgery. Best results will be achieved with the power on as the jaws close, using copious irrigation to prevent sticking and not firing the blade until the crushed tissue is observed. With this technique, intact vessels will be seen and can be burned, clipped, or stapled. LigaSure is now preferred, as, if used correctly, vessels will be preserved, rather than harmonic shears, which will divide vessels.

♦ Any bleeding can usually be controlled by the lifting up maneuver, with an instrument placed in the groove of the hepatogastric ligament and pressed up and to the right (Figure 9-5) or with direct pressure over the bleeder. Completion of the resection with staplers may stop hemorrhage, but occasionally, suturing is required.

♦ Laparoscopic control is preferred to conversion, but if progress is slow, conversion is essential.

♦ The cut surface is then inspected for bile leaks, which can be clipped or sutured.

♦ The specimen can be removed whole through a lower abdominal incision. If benign, then it can be morcellated and taken out via the umbilicus.

Step 5. Pearls and pitfalls

♦ This is the easiest of liver resections, open or laparoscopic.

♦ Patients can still die, from bleeding, or injury to adjacent organs, such as the heart or esophagus.

♦ Do not use staplers for the first time on a vascular organ in a live human. Become familiar with them first. They must be kept rock steady when firing, as slight movements of the surgeon’s hand can be magnified and lead to tearing of vessels. Make certain that the position of both blades is known before firing, as once used, there is no going back!

♦ Carbon dioxide gas embolism is not a clinical problem. Air embolism can be. Argon embolization from argon beam coagulation devices has been reported and if using, one must open a port to vent the abdomen and never apply the beam over an open vein.

Chang S, Laurent A, Tayar C, et al. Laparoscopy as a routine approach for left lateral sectionectomy. Brit J Surg. 2007;94;1:58-63.

O’Rourke N, Shaw I, Nathanson L, et al. Laparoscopic resection of hepatic colorectal metastases. HPB. 2004;6(4):230-235.

Strasberg S, Pang YY. The Brisbane 2000 terminology of liver anatomy and resections, IHPBA. HPB, vol 2. 2000:333-339.