Liver, Gallbladder, and Pancreas

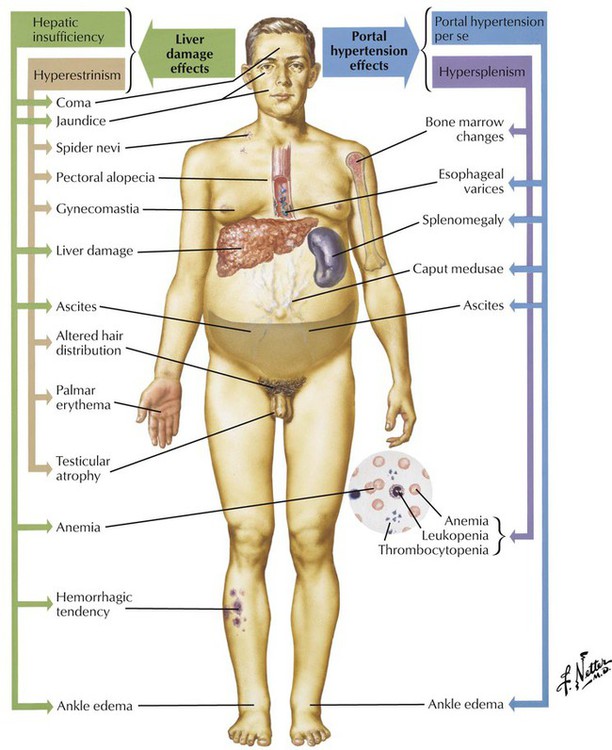

The liver maintains the physiologic and metabolic balance of the body. Therefore, disease of the liver may have numerous effects throughout the body: it may cause disturbances in carbohydrate, lipid, amino acid, and vitamin metabolism and interfere with protein synthesis, blood clotting, and detoxification of endogenous and exogenous substances (Table 5-1).

TABLE 5-1

CLINICAL FEATURES OF LIVER FAILURE

| Clinical Feature | Pathogenesis |

| Jaundice | a. Intracellular retention of bilirubin (hepatocyte failure) b. Intercellular and canalicular (bile stasis) |

| Malabsorption, weight loss, bleeding tendency, muscle wasting | Bile, enzyme, and vitamin deficiency |

| Edema, muscle wasting | Decreased protein (albumin) synthesis |

| Spider nevi, palmar erythema, gynecomastia | Disturbed hormone metabolism |

| Ascites, splenomegaly, varices (gastroesophageal) | Portal hypertension |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | Toxic metabolites (acetoin, acyloin, ammonia) |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | Cause unknown (renal vasoconstriction?) |

Inflammatory Diseases of the Liver

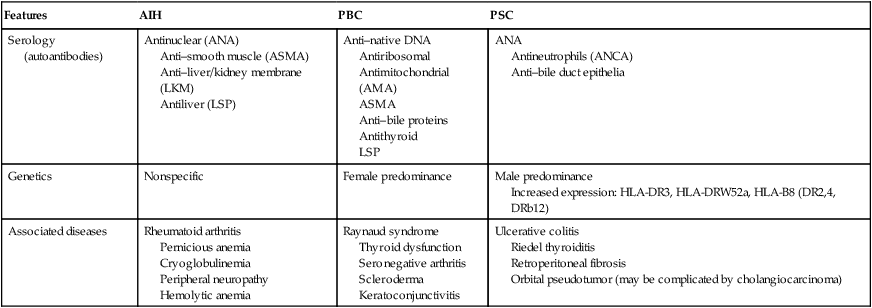

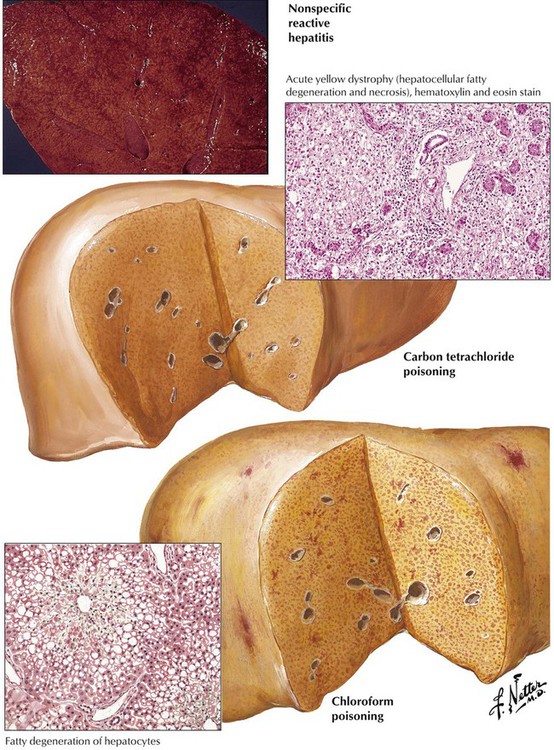

Noninfectious causes of liver inflammation include toxic and immunologic disorders of the liver (see Table 5-2). These are discussed together because certain forms of toxic hepatitis may mimic autoimmune disorders or may be mediated through hypersensitivity reactions. A large variety of substances can cause liver damage, and they are associated with an equally large variety of lesions. A selection is shown in Table 5-3.

TABLE 5-2

CHARACTERISTICS OF PRIMARY AUTOIMMUNE DISORDERS OF THE LIVER*

| Features | AIH | PBC | PSC |

| Serology (autoantibodies) | Antinuclear (ANA) Anti–smooth muscle (ASMA) Anti–liver/kidney membrane (LKM) Antiliver (LSP) |

Anti–native DNA Antiribosomal Antimitochondrial (AMA) ASMA Anti–bile proteins Antithyroid LSP |

ANA Antineutrophils (ANCA) Anti–bile duct epithelia |

| Genetics | Nonspecific | Female predominance | Male predominance Increased expression: HLA-DR3, HLA-DRW52a, HLA-B8 (DR2,4, DRb12) |

| Associated diseases | Rheumatoid arthritis Pernicious anemia Cryoglobulinemia Peripheral neuropathy Hemolytic anemia |

Raynaud syndrome Thyroid dysfunction Seronegative arthritis Scleroderma Keratoconjunctivitis |

Ulcerative colitis Riedel thyroiditis Retroperitoneal fibrosis Orbital pseudotumor (may be complicated by cholangiocarcinoma) |

Overlap syndromes combine features of cholestatic and chronic hepatitic forms of diseases, e.g., AIH + PBC, PBC + PSC, or PBC + sarcoidosis.

*AIH indicates autoimmune hepatitis; PBC, primary biliary cirrhosis; PSC, primary sclerosing cholangitis.

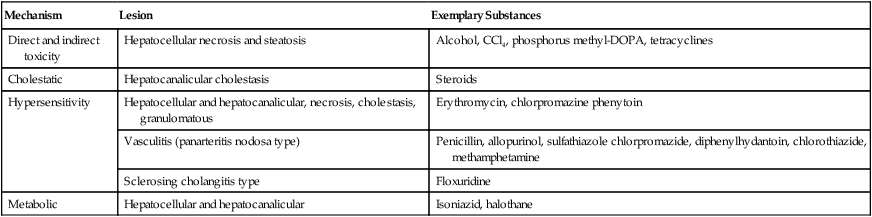

TABLE 5-3

TOXIC HEPATITIS AND ITS LESIONS

| Mechanism | Lesion | Exemplary Substances |

| Direct and indirect toxicity | Hepatocellular necrosis and steatosis | Alcohol, CCl4, phosphorus methyl-DOPA, tetracyclines |

| Cholestatic | Hepatocanalicular cholestasis | Steroids |

| Hypersensitivity | Hepatocellular and hepatocanalicular, necrosis, cholestasis, granulomatous | Erythromycin, chlorpromazine phenytoin |

| Vasculitis (panarteritis nodosa type) | Penicillin, allopurinol, sulfathiazole chlorpromazide, diphenylhydantoin, chlorothiazide, methamphetamine | |

| Sclerosing cholangitis type | Floxuridine | |

| Metabolic | Hepatocellular and hepatocanalicular | Isoniazid, halothane |

There are 3 major groups of autoimmune disorders affecting the liver: primary hepatic autoimmune diseases (Table 5-3), liver diseases with secondary autoimmune component, and systemic autoimmune diseases involving the liver.

Cystic Fibrosis (Mucoviscidosis)

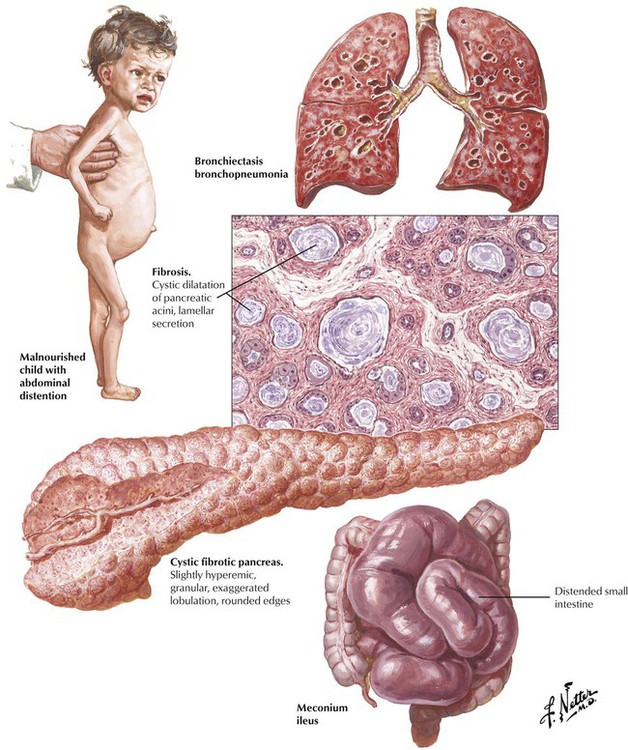

Cystic fibrosis (CF) is the most common autosomal recessively inherited disease in children and young adults, with an incidence in Western populations of 1 in 2000 live births. It is caused by variable mutations of the CF gene on chromosome 7 (7q31-32). The primary defect caused by these mutations is in chloride ion channels, which transport chloride ions across epithelial barriers. Deficient chloride ion transport interferes with sodium and water secretion in exocrine glands, resulting in the production of a viscous mucoid material that obstructs glandular ducts in salivary glands, bronchial glands, the pancreas, and others. (See also Fig. 3-3.)

Neoplasms of the Pancreas

TABLE 5-4

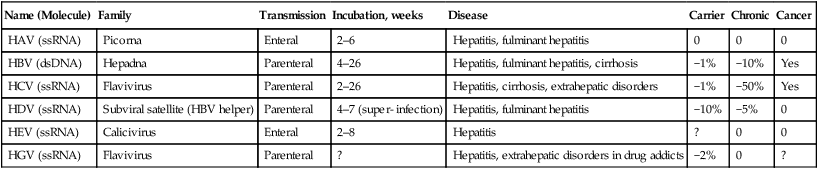

MEMBERS AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE HEPATITIS VIRUSES*

| Name (Molecule) | Family | Transmission | Incubation, weeks | Disease | Carrier | Chronic | Cancer |

| HAV (ssRNA) | Picorna | Enteral | 2–6 | Hepatitis, fulminant hepatitis | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| HBV (dsDNA) | Hepadna | Parenteral | 4–26 | Hepatitis, fulminant hepatitis, cirrhosis | −1% | −10% | Yes |

| HCV (ssRNA) | Flavivirus | Parenteral | 2–26 | Hepatitis, cirrhosis, extrahepatic disorders | −1% | −50% | Yes |

| HDV (ssRNA) | Subviral satellite (HBV helper) | Parenteral | 4–7 (super- infection) | Hepatitis, fulminant hepatitis | −10% | −5% | 0 |

| HEV (ssRNA) | Calicivirus | Enteral | 2–8 | Hepatitis | ? | 0 | 0 |

| HGV (ssRNA) | Flavivirus | Parenteral | ? | Hepatitis, extrahepatic disorders in drug addicts | −2% | 0 | ? |

TABLE 5-5

GROSS FEATURES AS RELATED TO THE PATHOGENESIS OF LIVER CIRRHOSIS*

| Gross Appearance | Pathogenesis |

| Diffuse, finely nodular (classic Laennec type: with atrophy) | Post–hepatitis virus cirrhosis |

| Same with or without fatty infiltration | Post–alcoholic cirrhosis |

| Diffuse, medium-sized nodular, dark purple (classic Hanot type with hypertrophy) | Chronic congestive (practically only seen in constrictive pericarditis) |

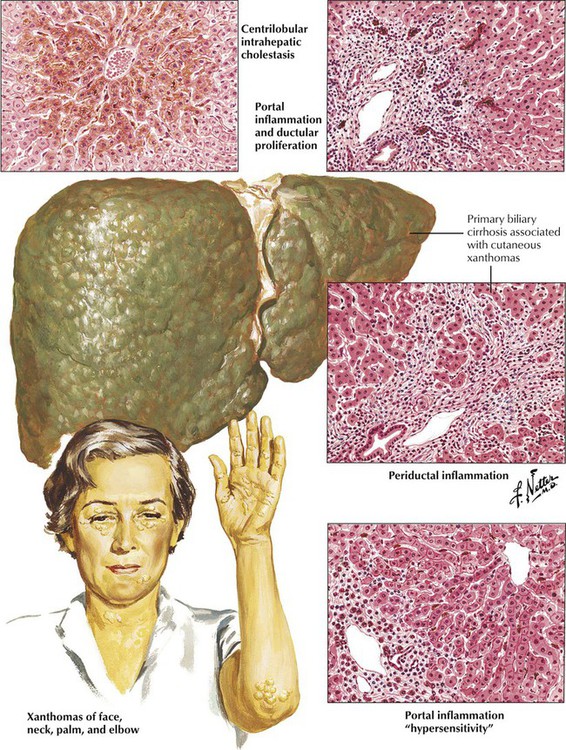

| Same with severe jaundice (green liver) | Primary biliary cirrhosis or chronic sclerosing cholangitis |

| Same with “dirty” gray-brown appearance (and similarly pigmented pancreas) | Hemochromatosis, Wilson disease |

| Diffuse, irregularly nodular, preferentially small- to medium-sized nodular | Autoimmune hepatitis and cirrhosis |

| Irregular, medium- to large-sized nodular, with jaundice (green liver) | Secondary biliary cirrhosis (i.e., extrahepatic bile duct obstruction) |

| Same with regular color or with fatty infiltration | “Postnecrotic” cirrhosis of variable etiology (e.g., post-HSV + alcoholic or other toxic influences) |

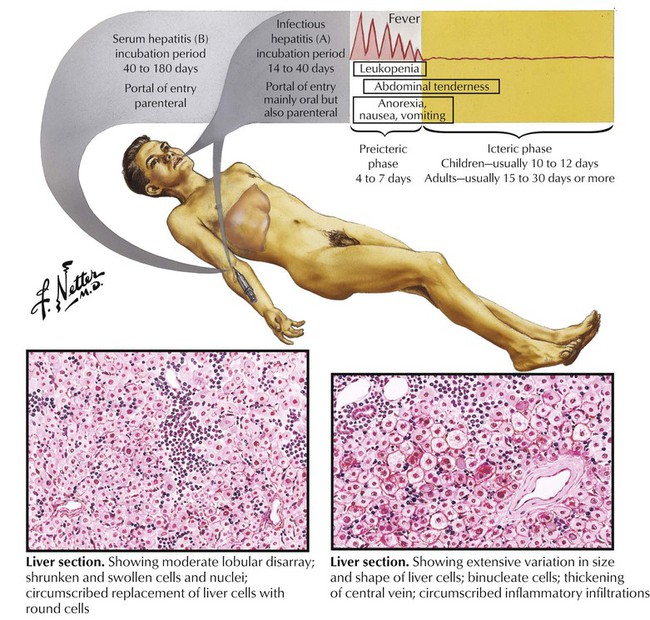

Acute viral hepatitis, an inflammatory disease of the hepatic parenchyma, is caused most frequently by the hepatitis viruses (HVs) and less frequently by other viruses (Table 5-4). In the Western world, HBV and HBC are most prevalent. Disease symptoms develop between 2 and 26 weeks after the onset of immune reactions against virus/virus-infected cells. The pathogenesis of liver injury in viral hepatitis is not completely clear, although a cytotoxic T-lymphocyte reaction against hepatocytes presenting viral antigens seems to be the key reaction. Histology shows many lymphocytes invading the liver parenchyma from portal triads, which causes adjacent hepatocellular necroses (piecemeal necroses). Infected hepatocytes change to a ground-glass appearance. In more severe disease, infected hepatocytes show ballooning degeneration. In addition, there are single or multiple hepatocellular coagulation necroses of virus-infected hepatocytes (Councilman bodies) or lytic necroses (dropout necroses).

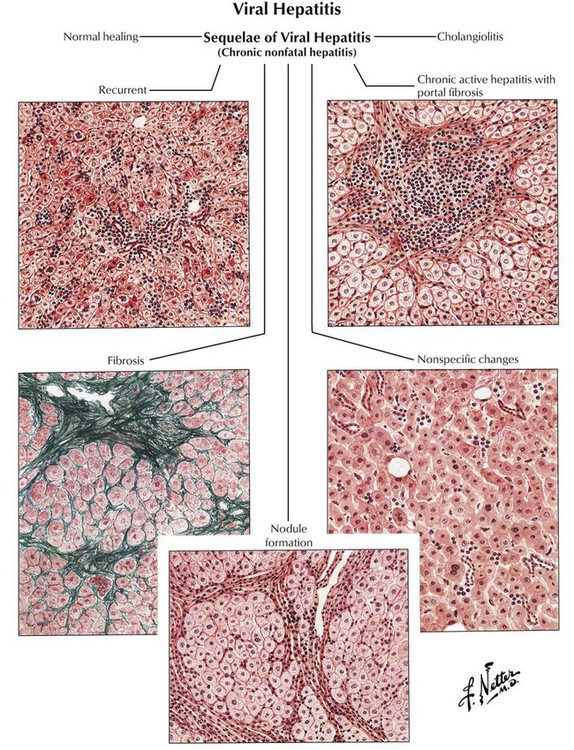

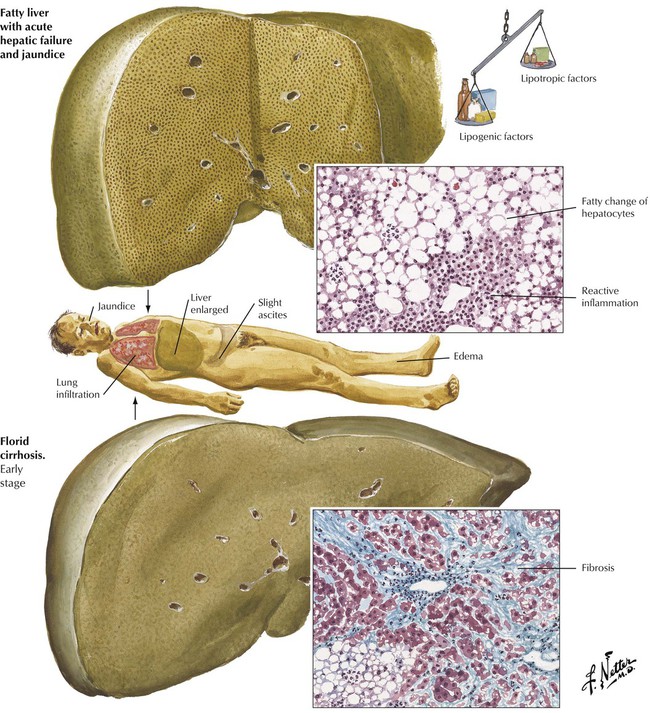

The onset of chronic hepatitis is characterized by reticular fibrosis, which surrounds necrobiotic hepatocytes and frequently precedes the formation of collagen fibrils. Collagenous fibrosis replaces damaged liver parenchyma, starting from a simple portal fibrosis and progressing to formation of fibrous septae (septal fibrosis) and final invasion and disruption of the acinus (pseudoacinus formation). The final stage of this fibrotic process is the development of hepatic cirrhosis with diffuse fine-nodular change. The general outcome of infections with HBV and HCV is usually the following: (1) symptomatic acute hepatitis (35% in HBV, 10% in HCV); (2) development of chronic hepatitis (10% in HBV, 50-70% in HCV); (3) development of cirrhosis (10-30% in HBV, at least 35% in HCV); (4) development of HCC (roughly estimated at 5-10% in both HBV and HCV). An additional threat is the high incidence of an asymptomatic carrier state in 70% to 90% of patients.

Cirrhosis of the liver with its extensive scarring and structural and functional alterations constitutes the end stage of various chronic inflammatory liver diseases. Histologically, it is defined by the triad of fibrosis, umbau (reconstruction with pseudoacini), and excess regeneration (hepatocellular nodules, bile duct proliferation). Pseudoacini (pseudolobules) originate from collagen fibers that invade the hepatic acinus, causing it to split. The sections that separate from the hepatic acinus do not contain a central vein and cannot function adequately. This scenario is further complicated by regenerative liver nodules. In the Western world, alcoholic liver cirrhoses constitute approximately 60% to 70% of all cases. Approximately 10% of cases are HV-induced cirrhoses, and 5% to 10% are primary and secondary biliary cirrhoses. Diagnostic gross features of different types of liver cirrhoses are outlined in Table 5-5.

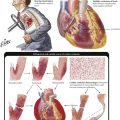

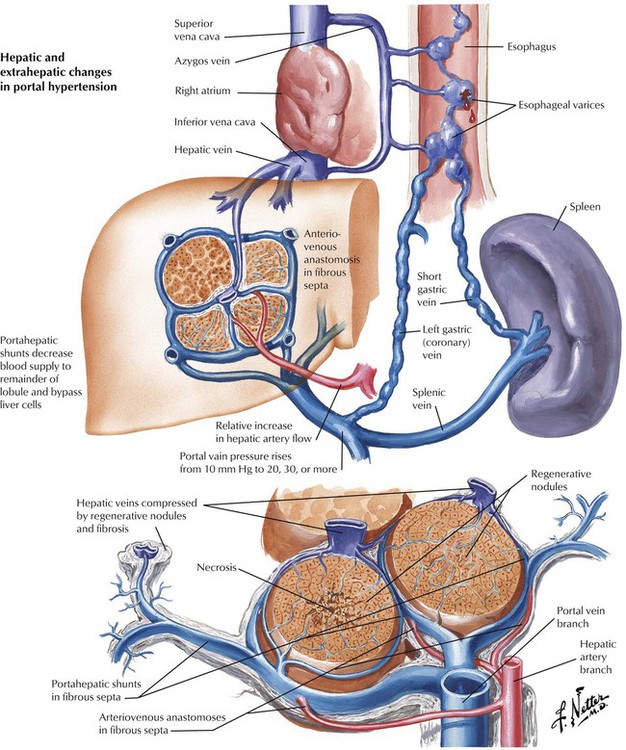

Fibrosis and umbau cause severe obstruction of intrahepatic blood flow with portal hypertension. Other causes of portal hypertension include thrombosis of major hepatic veins (Budd-Chiari syndrome) and of the portal vein. Symptoms of portal hypertension are splenomegaly, ascites, and gastroesophageal varices. Ascites is usually the result of increased venous pressure, hypoalbuminemia (secondary to hepatocellular damage with reduced protein synthesis), and sodium retention (secondary by hepatocellular damage with diminished inactivation of antidiuretic hormone [ADH] and aldosterone). Bleeding from esophageal varices is a major cause of death in patients with liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension.

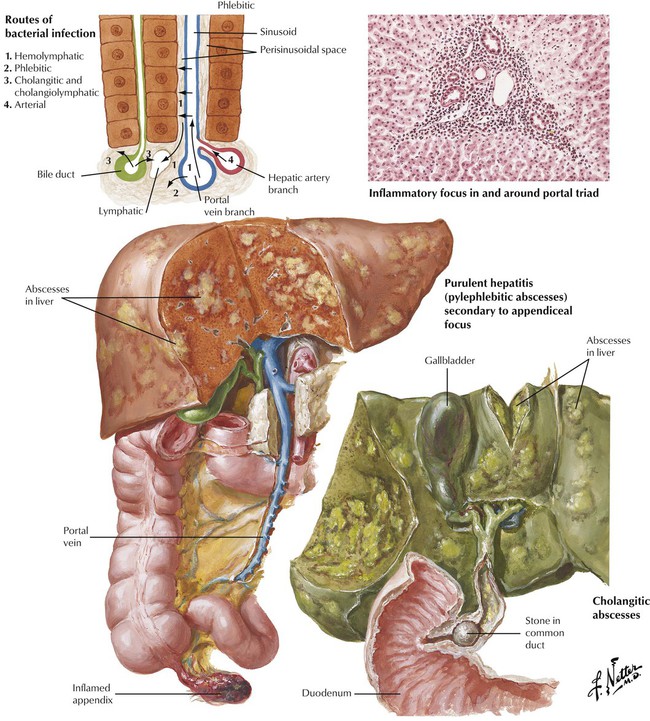

Bacterial infections of the liver frequently occur as part of a systemic infection (septic abscesses) or through lymphatic (lymphangitis) or venous (pylephlebitis) spread from infections of adjacent organs such as appendicitis, infectious cholangitis, diverticulitis, or pancreatitis. Microorganisms entering the liver are taken up by sinusoidal Kupffer cells, which proliferate to form small Kupffer cell nodules intermixed with hematogenous polymorphonuclear leukocytes (neutrophils). The neutrophils are even more pronounced in and around lymph channels and veins. A more toxic inflammatory reaction produces circumscribed necroses and abscesses in the liver.

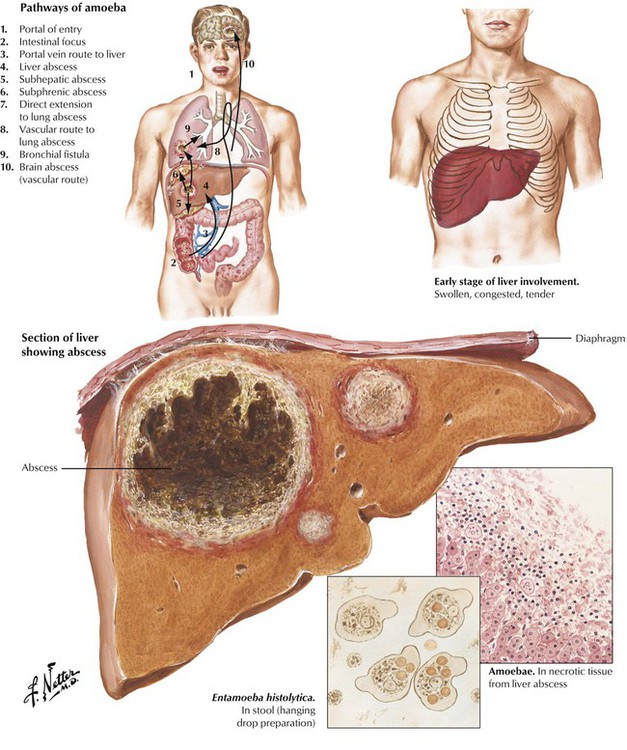

Liver abscesses are the most common extraintestinal complication of amebiasis. They occur infrequently in the average US population but are more prevalent in homosexual men and especially in populations of tropical and subtropical zones (tropical abscesses). Abscesses impress as large well-circumscribed masses in the liver, which empty a dirty brownish material onto a cut surface. Amebic trophozoites accumulate in the border zone of abscess and viable liver parenchyma. Bacterial superinfection is frequent. Complications are rupture of the abscess into the peritoneal cavity or hematogenous spread of amebae with development of multiple lung and brain abscesses. Mortality in this stage is high (up to 40%).

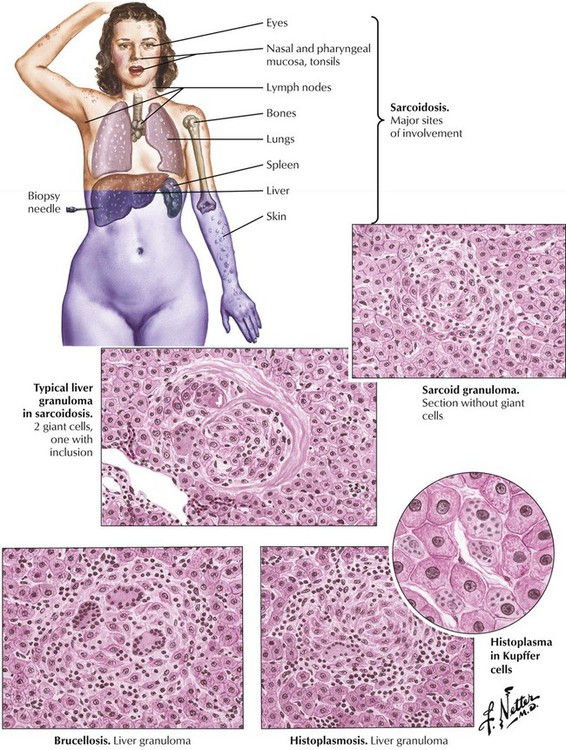

Granulomatous hepatitis is associated with systemic infections such as tuberculosis, typhoid fever, and sarcoidosis. In addition, brucellosis (Mediterranean fever, undulant fever) is a zoonosis caused by microorganisms of the genus Brucella (B abortus Bang, B melitensis, B suis, B canis). Infection follows direct contact with infected animals or foods. Bacteria invade through the alimentary tract, the lungs, or skin abrasions and localize in cells of the reticuloendothelial tissues. Liver biopsy results reveal a mild nonspecific hepatitis with or without noncaseating granulomas, which are sometimes suppurative and calcifying. Histoplasmosis is a systemic soil-borne fungal infection caused by inhalation of Histoplasma capsulatum. Systemic histoplasmosis affects the liver with epithelioid cell granulomas with or without caseation.

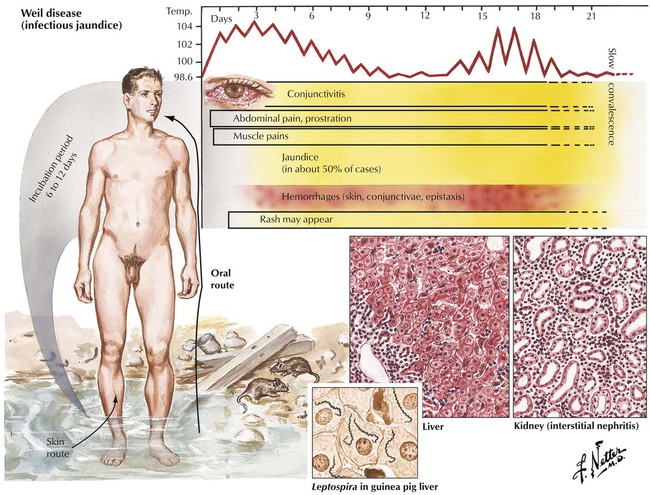

Spirochetal infections of the liver include Weil disease and syphilis. Weil disease (infectious jaundice) is caused by the spirochete Leptospira, a widespread zoonotic inhabitant in wild rats and mice. Liver involvement occurs in 50% of cases with noncharacteristic centrilobular and midzone necroses, Councilman bodies and ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes with signs of regeneration (anisonucleosis, multinucleated cells, mitotic figures), portal inflammation, and Kupffer cell hyperplasia. The liver appears grossly yellow-green because of combined hepatocellular degeneration, hemolysis, and cholestasis. Leptospires can be identified microscopically in Kupffer cells and especially in renal tubular cells in approximately 65% of patients. Severe disease may be fatal. Syphilitic lesions occur in 2 forms: congenital syphilis, with mild triaditis, mild hepatocellular necrosis, and diffuse fibrosis, and tertiary syphilis, characterized by multiple granulomas (gummas) and scarring.

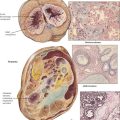

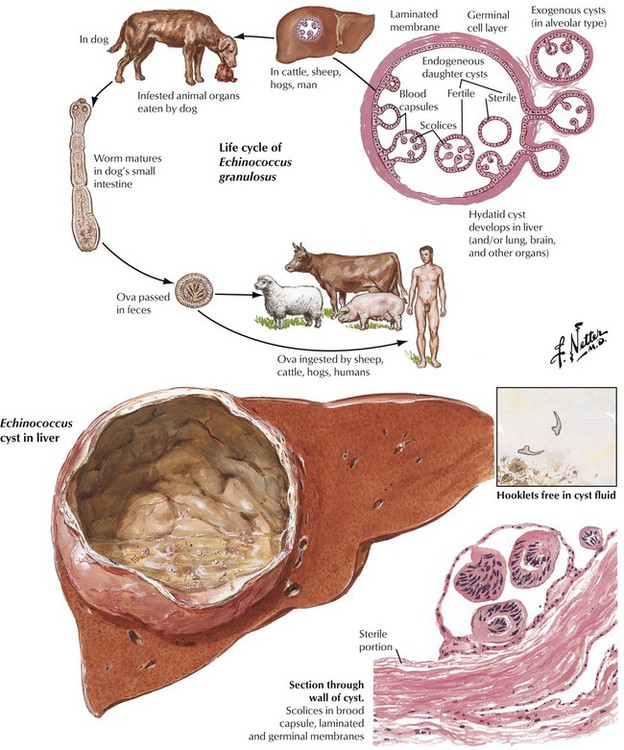

Parasitic diseases of the liver include infestations by tapeworms of Echinococcus species. Echinococcus infection is common in the Mediterranean, southern South America, the Middle East, central Asia, and Africa. Incidence is low in the United States. Humans become infected through ingestion of eggs in contaminated food. Approximately 60% of cysts develop in the liver, where they usually remain asymptomatic. Other sites that can be involved are the lungs, the brain, the kidneys, soft tissues, and bone. When cysts grow larger than 10 cm in diameter, they may cause compression of liver tissue with jaundice, portal hypertension, and cholangitis. Resorption of fluid materials from cysts causes immunologic sensitization of patients with secondary arthritis and membranous glomerulonephritis. Rupture of cysts in such conditions can lead to anaphylactic shock.

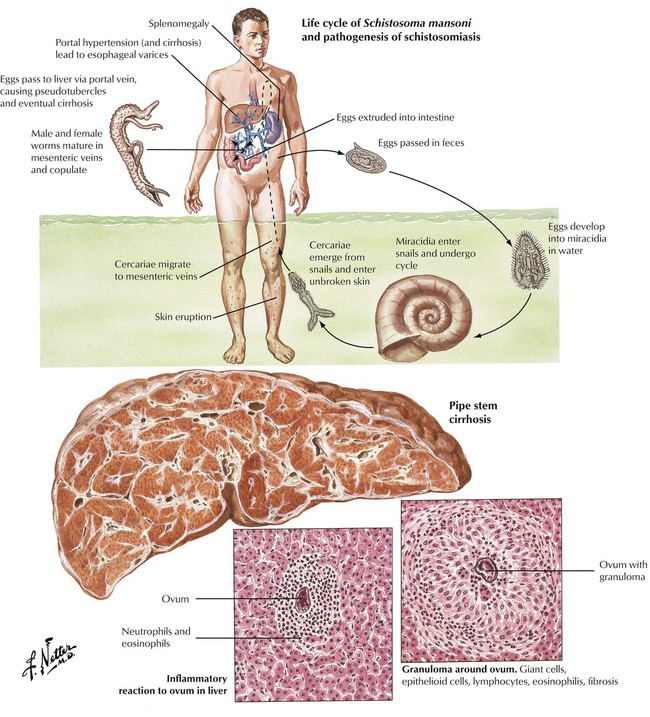

Schistosomiasis is caused by trematodes of the Schistosoma genus. It is endemic in large parts of Africa, the Americas, and the Far East. Humans are the principle hosts for the adult worms, which reside in the intestines, the urinary bladder, and the venous system. Sexual reproduction of worms produces eggs, which infest water and develop into a ciliated intermedia, the miracidia. Miracidia penetrate into a snail where they reproduce asexually within 4 to 6 weeks to produce hundreds of cercariae, which enter humans through the skin when they bathe in infected waters. The cercariae migrate to the lungs and mature into adult worms, which travel via blood vessels (veins) to distant organs. Up to 10% of patients in endemic regions develop schistosomiasis of the liver, which consists of granulomatous hepatitis (around schistosomal eggs) with eosinophils and portal fibrosis. Progression to cirrhosis is exceptional.

In Western countries, alcoholism is the most frequent cause of fatty liver (hepatic steatosis) and “toxic” hepatitis. Seventy percent of liver cirrhoses (Table 5-3) are alcoholic cirrhoses. Chronic daily intake of 80 to 160 g ethanol increases peripheral lipolysis and causes influx of fatty acids into the liver, enhances intrahepatic fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis, and reduces fatty acid oxidation and the release of lipoproteins. Hepatic steatosis develops in 3 stages: stage I fatty liver (simple steatosis): 50% or more of hepatocytes show fatty infiltration; stage II fatty liver hepatitis (alcoholic hepatitis): steatosis, focal hepatocellular necrosis/degeneration (fatty and ballooning degeneration of hepatocytes with alcoholic hyaline [Mallory bodies]), and reactive-type hepatitis with or without reticular and septal fibrosis; stage III fatty liver cirrhosis (alcoholic cirrhosis): steatosis (may be absent in later stages) with diffuse micronodular cirrhosis.

Significant fatty infiltration and necrosis result from fungus poisoning (especially with Amanita muscaria) or exposure to organic solvents (chloroform) or phosphorus, all of which cause rapidly progressive liver failure and death in liver coma. Other toxic injuries to the liver—with or without steatosis—are outlined in Table 5-3. Another toxic condition with extensive hemorrhagic necroses in the liver is eclampsia (toxemia of pregnancy), a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy with edema, proteinuria, vascular endothelial injury, and coagulation abnormalities. The latter causes disseminated intravascular coagulation, with the most prominent lesions in the liver, the brain, and the kidneys. Patients usually die of cerebral hemorrhages and symptoms of coma and convulsions.

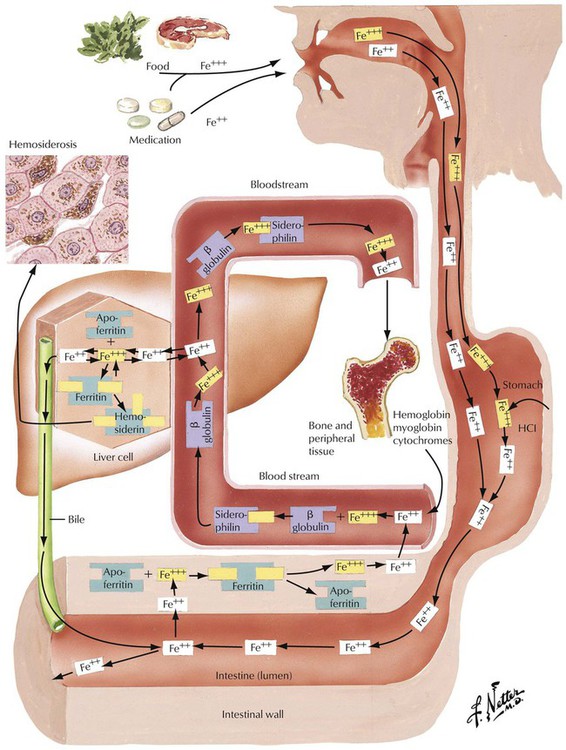

Hemochromatosis, a common autosomal recessive disorder, is characterized by iron accumulation in the liver, the heart, the pancreas, and other organs. It affects men 10 times more frequently than women and is based on a genetic change on chromosome 6, gene HLA-H (HFE gene), which controls iron absorption. Iron accumulates in the liver and other organs at a rate of up to 1 g/y; clinical symptoms occur when the body iron stores exceed 20 g (normal, 3–4 g). Liver tissue contains 6000 to 18,000 µg/g dry weight iron as compared with the normal storage of 300 to 1400 µg/g. Hemosiderosis (secondary exogenous hemochromatosis) represents a secondary iron overload syndrome, usually after hypertransfusion with blood.

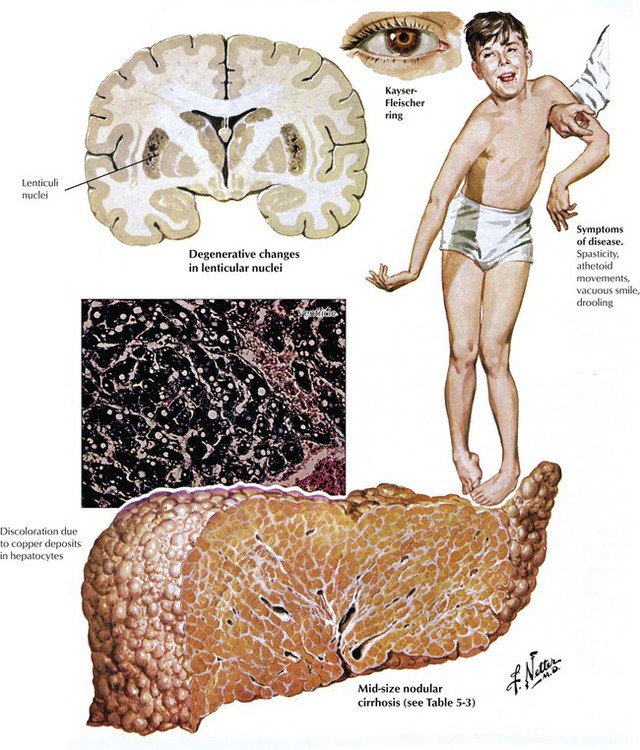

Wilson disease (WD; hepatolenticular degeneration) is an autosomal recessive disorder of hepatobiliary copper excretion with progressive accumulation of the toxic metal in the liver, the brain, the eyes, and many other organs. The genetic disturbance is located on chromosome 13. The incidence of WD is 1 : 30,000. First symptoms are usually noted during the second decade of life. Liver pathology shows acute (necrotizing) hepatitis, chronic active hepatitis with cholestasis, or cirrhosis with or without copper deposition (copper usually in excess of 250 µg/g dry weight). Hepatic changes without excess copper are indistinguishable from viral hepatitis and cirrhosis. Of diagnostic value are copper deposits in the corneal limbus, which impress on inspection as brown-greenish rings (Kaiser–Fleischer rings). WD runs a progressive downhill course until copper is reduced by chelating agents, except for rare cases of fulminant hepatitis, which have an unfavorable prognosis.

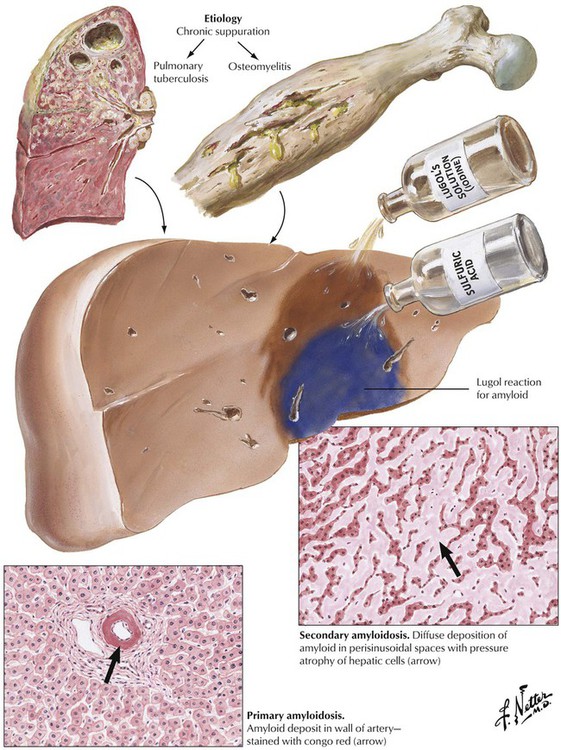

Amyloidosis of the liver occurs in 2 forms: diffuse perisinusoidal amyloidosis (secondary amyloidosis) after chronic infections, and focal vascular (portal) amyloidosis (primary amyloidosis). Secondary amyloidosis causes enlargement of the liver with effacement of the gross lobular structure. The cut surface is smooth and rubbery and of yellowish-brown color. Primary amyloidosis, which is not associated with inflammatory diseases of other organs, frequently follows abnormal protein production by plasma cells (plasma cell dyscrasia). Therefore, it is frequently accompanied by diffuse plasmacytosis or malignant plasmacytoma. Vascular (primary) amyloidosis typically involves mesenchymal tissues of other organs such as the myocardium, skeletal muscle, the tongue, the skin, the kidneys, and the spleen. Both forms of liver amyloidosis are part of a systemic process, and involvement of other organs may determine the outcome (e.g., cardiac or renal failure).

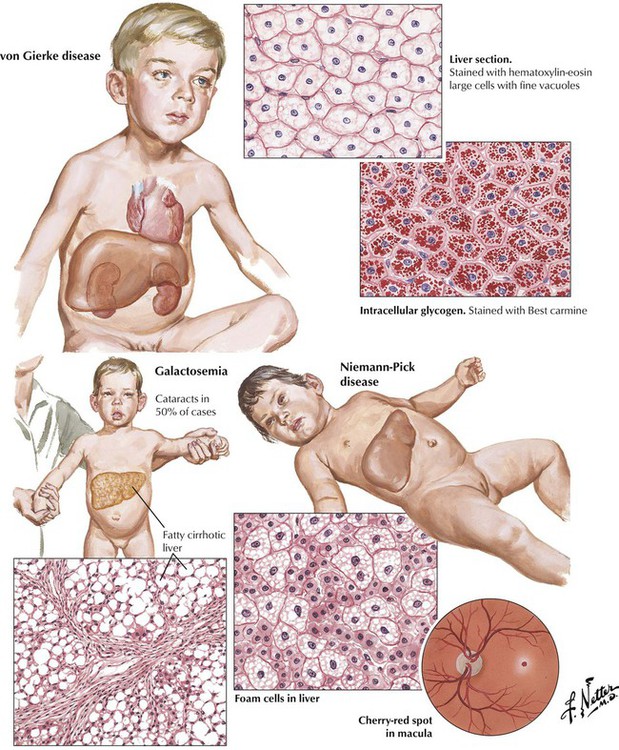

Storage diseases (thesaurismoses) affect children preferentially and cause hepatomegaly. Most common are glycogen storage diseases (von Gierke disease and others) and sphingolipidoses (Niemann-Pick, Tay-Sachs, and Gaucher diseases). Nonmetabolized substances accumulate because of genetic mutations of lysosomal hydrolytic enzymes. Glycogen preferentially accumulates in hepatocytes in the liver, whereas other substances are taken up more intensely by cells of the reticulohistiocytic (phagocytic) series (Kupffer cells) in the liver. These cells are greatly enlarged, leading to compression and atrophy of hepatocytes. Galactosemia results from deficiency of a transferase that converts galactose into glucose, resulting in deposition of galactose in several organs, such as the liver, the spleen, the kidneys, the central nervous system (CNS), and the eyes. Malnutrition in these infants contributes to diffuse fatty degeneration of hepatocytes with development of liver cirrhosis and portal hypertension.

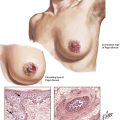

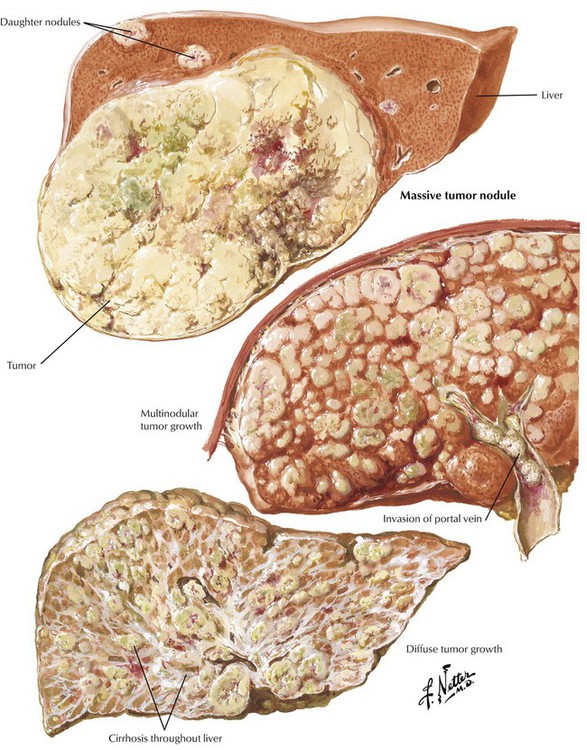

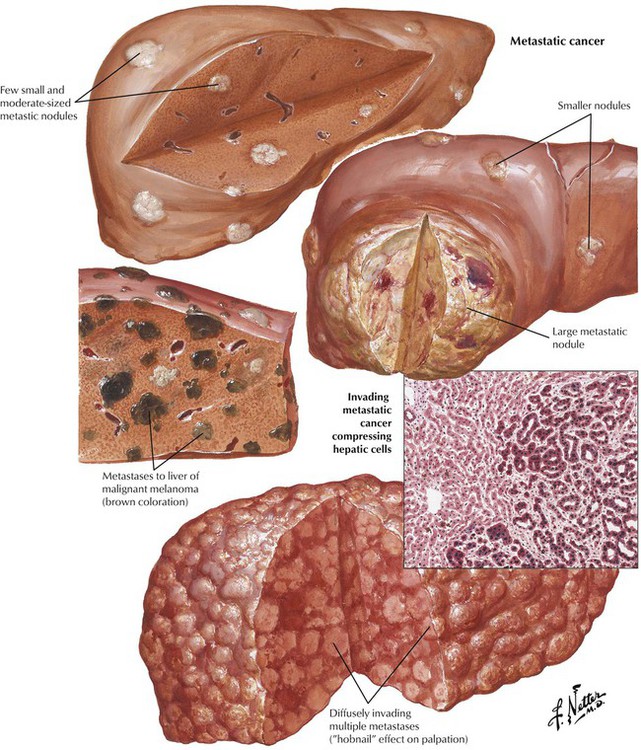

Hepatocellular carcinoma, which occurs in adults with cirrhotic livers (in children it is seen without cirrhosis), is associated with persistent infection by HBV and HCV, including asymptomatic carriers (i.e., patients with occult liver cirrhosis). Other patients with liver cirrhosis who are at risk for developing HCC are those with hemochromatosis and α1-antitrypsin deficiency. Most patients with alcoholic cirrhosis and HCC are also infected with HCV or HBV. The gross picture of HCC is that of one or several irregular soft yellowish-green nodules in a cirrhotic liver with intrahepatic (parenchymatous, intravascular) spread. The histologic appearance varies from a trabecular and acinar pattern of well-differentiated hepatocytes to a poorly differentiated fibrolamellar tumor or a tumor with cholangiocellular features. The ascites color may change to bloody. Serum levels of α-fetoprotein increase dramatically (400–4000 ng/mL).

Although more rare than HCC, intrahepatic (peripheral) CAC also is associated with cirrhosis. It is derived from small intrahepatic bile canaliculi with lymphatic spread to portal lymph nodes (less frequently than HCC via hepatic vessels). The tumor is usually well differentiated with clearly defined tubular structures and pronounced desmoplasia (tumor fibrosis). Bile pigment is absent.

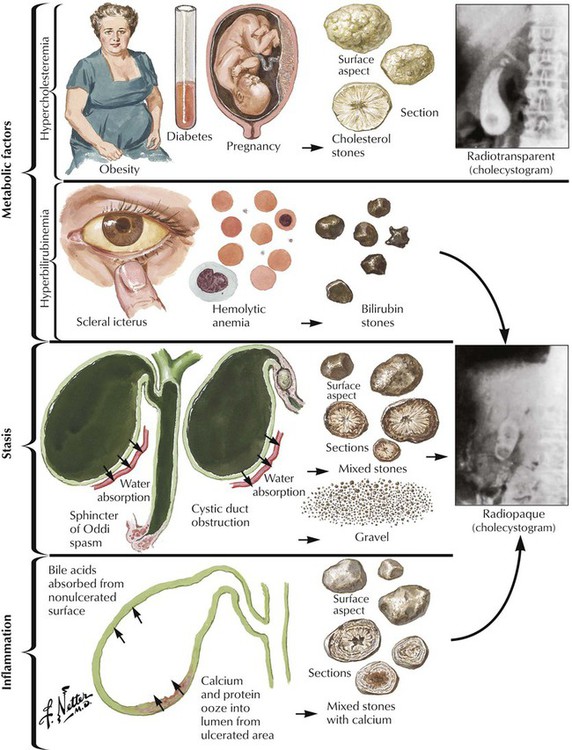

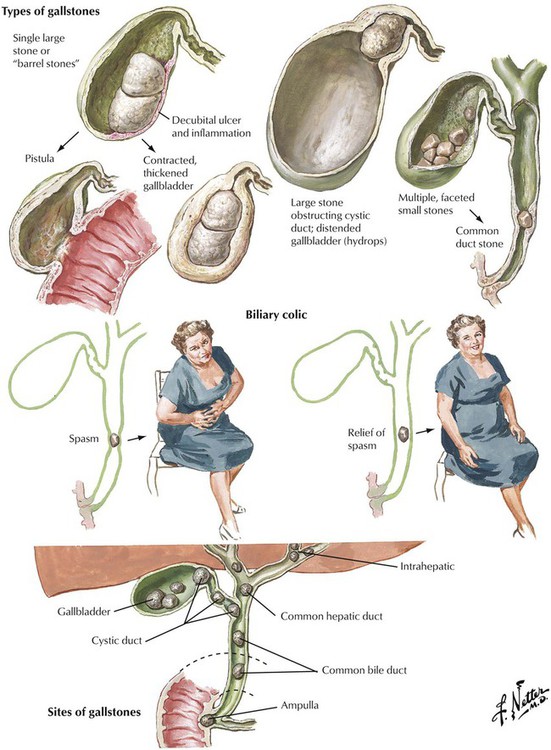

Cholelithiasis (CL) results from the formation of stones in the gallbladder and in large bile ducts. Bile stones are composed of bile (bile acids, bile pigments, and cholesterol) with various amounts of calcium. Stones are classified as cholesterol stones, pigment stones, and mixed stones according to the prevalent component. More than half of stones are cholesterol stones, which consist of precipitated cholesterol (nutritional hypercholesterolemia, reduced solubilization by bile acids) with crystal formation. Pigment stones are usually smaller and consist of blood pigments (calcium bilirubinate is contained in bilirubin stones). They occur most frequently in patients with some form of hemolytic anemia (e.g., thalassemia, sickle cell anemia) but also occur in patients with infections of the biliary tract. Mixed stones usually result from inflammation and bile stasis.

Only 20% of patients with CHL become clinically symptomatic. Complications usually arise from obstruction of bile passageways by stones, which results in acute severe pain (biliary colic) and inflammation. Obstruction by stones may occur at various sites from the cystic duct to the choledochus and the papilla. Papillary obstruction causes acute pancreatitis in cases of coincident obstruction of the pancreatic duct. Complications of chronic CHL are bile stasis, superinfection with pus accumulation in the bladder (empyema), perforation of a stone into the peritoneum with resultant peritonitis or into the intestines with eventual obstruction (gallstone ileus), and fibrous obstruction of the cystic duct with resorption of bile, which leaves a mucoid intraluminal fluid (mucocele). Stones in the common bile duct or in the major intrahepatic ducts cause obstructive cholestasis in the liver.

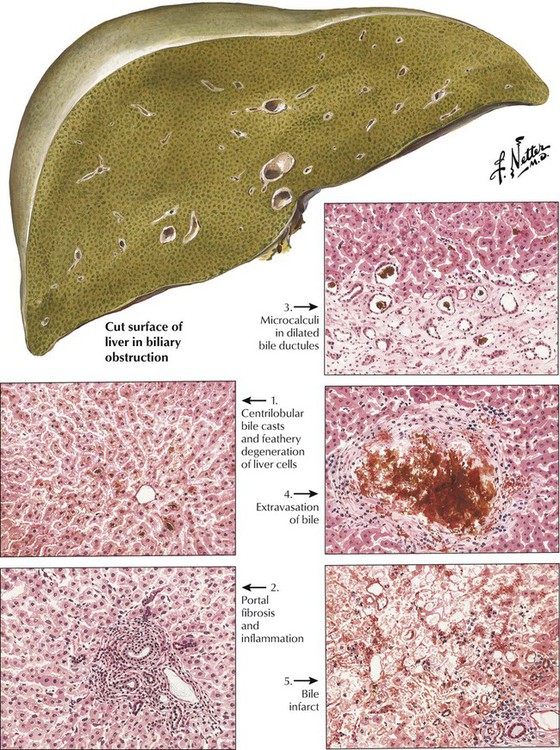

Extrahepatic biliary obstruction causes bile casts, which are most prominent in the peripheral part of the lobule. They are usually accompanied by secondary hepatocellular degeneration (feathery degeneration, see Figure 1-1, top right), portal inflammation (neutrophilic and lymphoplasmacytic), and portal and septal fibrosis. The liver is enlarged and dark green but rarely cirrhotic. Intrahepatic cholestasis shows portal and centrilobular bile stasis without major hepatocellular degeneration. Prominent reparative bile duct proliferation occurs in portal triads with chronic inflammation, progressive fibrosis, and, finally, cirrhosis. Intrahepatic cholestasis usually accompanies other liver diseases, such as viral or toxic hepatitis, but its etiology can remain obscure. In later stages, hepatocytes show ballooning degeneration, and chronic portal inflammation leads to portal and septal fibrosis with regenerative proliferation of bile ducts.

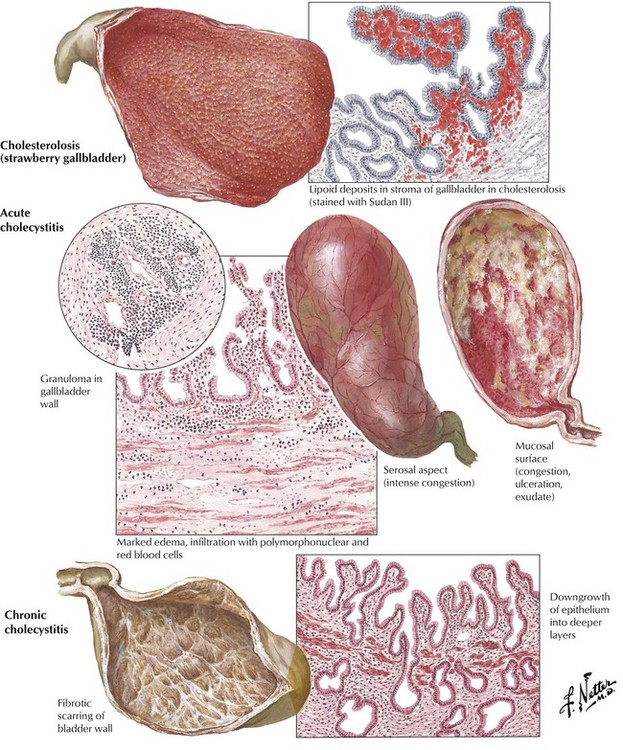

Acute and chronic cholecystitis, diffuse inflammations of the gallbladder wall, are most frequently caused by CHL. They can occur with or without lipid deposits in mucosal macrophages, causing typical foam cells. Cholecystitis not associated with CHL may be seen in infections (sepsis, salmonella), in autoimmune vasculitis (e.g., panarteritis nodosa), or secondary to trauma. Acute cholecystitis is characterized by edematous thickening of the bladder wall with neutrophilic infiltration and eventual hemorrhage. Cholesterol resorption may cause occasional foreign body granulomas (giant cells with cholesterol clefts). Empyema and perforation are possible complications. Chronic cholecystitis shows mucosal atrophy, fibrous thickening of the bladder wall, and hypertrophy and hyperplasia of deeper glands. There may be extensive adhesions of the gallbladder to adjacent organs (e.g., the large intestine).

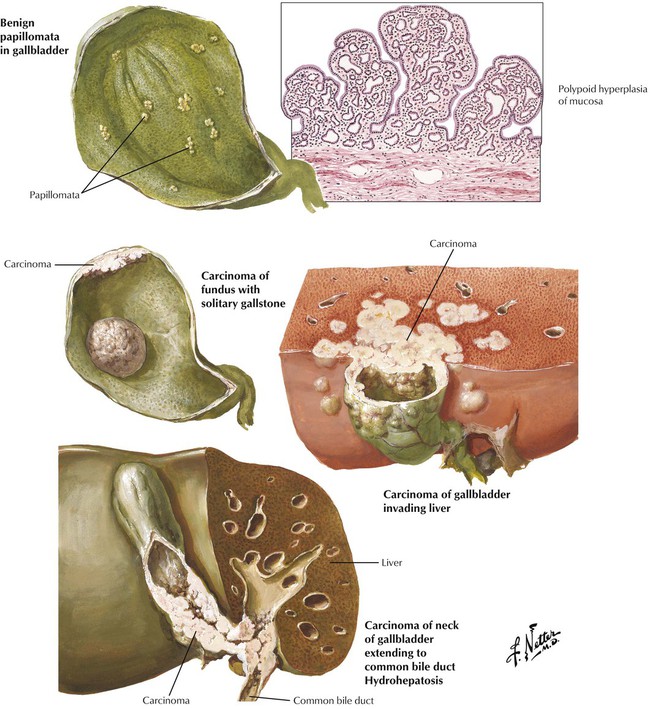

Adenocarcinoma of the gallbladder, the fifth most common tumor in the GI tract, usually occurs later in life. There are 2 major types: (1) a flat, scirrhous, and infiltrating form (not well differentiated) and (2) a polypoid-fungating form (well differentiated). More than 60% of these cancers are associated with CHL. Nearly all have spread to liver and peribiliary fat tissue at the time of the initial diagnosis so that the mean 5-year survival is only approximately 1%. Biliary adenocarcinoma metastasizes preferentially within the peritoneal cavity to regional lymph nodes and other organs of the GI tract. It spreads to the lungs less frequently.

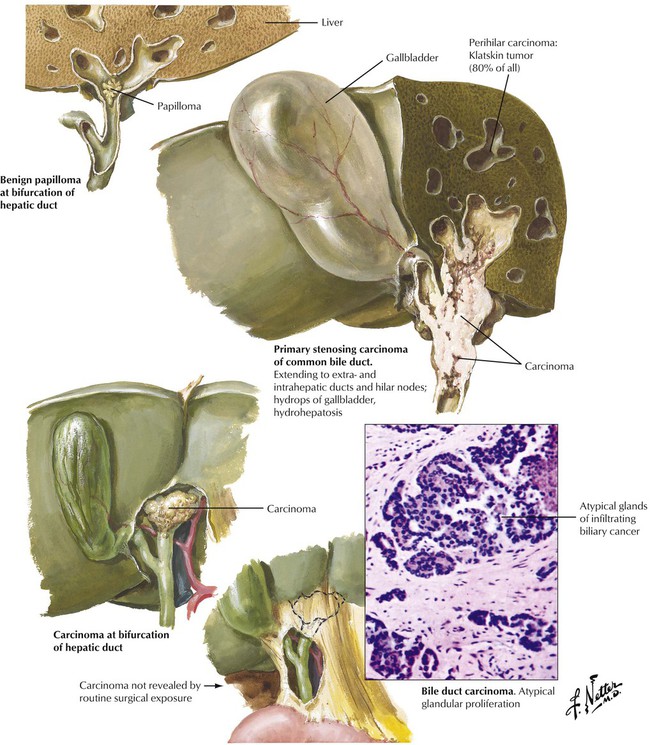

Adenocarcinoma of extrahepatic bile ducts and of the ampullary region occurs in older patients. It is not usually related to bile stones and is more frequent in areas where infestation with the fluke Clonorchis sinensis is endemic. Hepatic pathology secondary to obstruction and bile stasis causes liver enzymes to increase, especially alkaline phosphatase. Early detection while tumors are still small may result in a more favorable prognosis than in cancer of the gallbladder, with a mean 35% five-year survival for patients with ampullary cancers. Common adenocarcinoma of the bile ducts has usually spread at the time of diagnosis, rendering surgical resections incomplete and resulting in an average survival of 18 months.

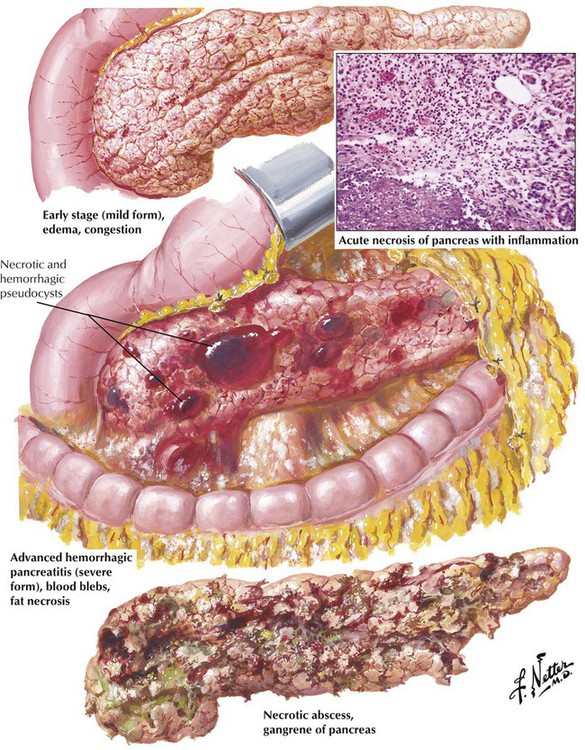

Acute pancreatitis presents in 3 forms: (1) a mild, self-limited disease with little destruction of acinar cells; (2) a recurrent inflammation, which progresses to chronic pancreatitis; or (3) a life-threatening disease with gross necrosis of pancreatic and fat tissue. The mild form is characterized by interstitial edema with neutrophilic infiltration and occasional acinar cell degeneration. Virally induced pancreatitis occurs as acute or chronic recurrent pancreatitis with a lymphocytic infiltrate, some epithelial necrosis (ductal and acinar), and occasional cytopathic changes (cytomegalic owl eye cells). In the severe form, massive enzymatic digestion by proteases causes extensive necroses and hemorrhage secondary to necrotic blood vessels. Lipases cause extensive necrosis of fat tissue (lipolytic necroses) with precipitation of calcium salts. Fatty acids and calcium form insoluble salts at the site of fatty necroses with a characteristic soapy appearance. There are few neutrophils and, eventually, granulation tissue. Massive necrosis may cause pancreatic pseudocysts on resorption of the necrotic debris.

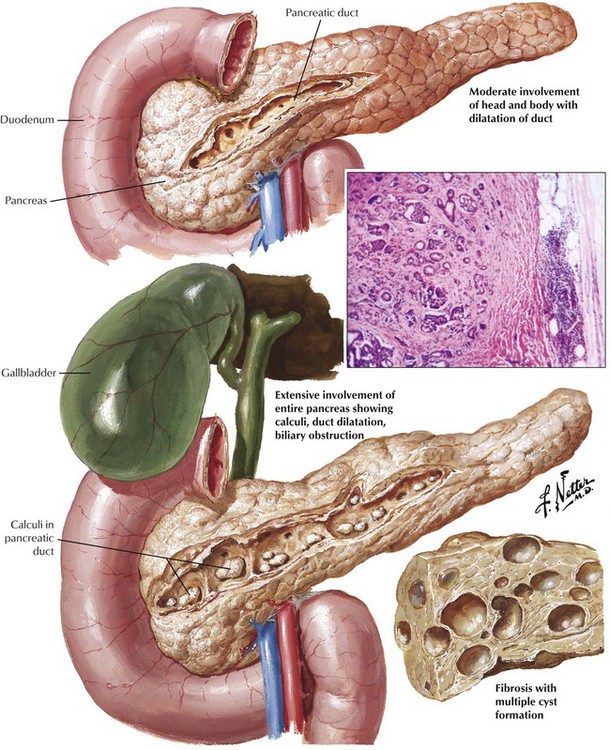

Chronic pancreatitis with progressive destruction of the parenchyma and fibrosis results from recurrent acute pancreatitis. Various lymphoplasmacytic infiltrates invade disrupted exocrine glandular acini. In end-stage disease, only pancreatic ducts and some islets may remain in the extensive scar tissue. In disease caused by long-term alcohol abuse, there is additional mucus plugging of major pancreatic ducts with secondary calcification (chronic calcifying pancreatitis). Other causes of chronic pancreatitis are mucoviscidosis (CF), which is also characterized by mucus plugging of ducts (chronic obstructive pancreatitis); WD; hemochromatosis; rare forms of hereditary pancreatitis (in childhood); and idiopathic forms. Chronic pancreatitis usually runs a long, debilitating course with a cumulative mortality of 50% in approximately 20 years.

More than 80% of patients with CF (mucoviscidosis) have visible secretory abnormalities of the pancreas, which cause mucus inspissation in major ducts and secondary atrophy of exocrine glands. Dilated and plugged ducts may cause multiple cysts, and degrading (sometimes superinfected) mucus leads to chronic resorptive inflammation with lymphoplasmacytic and phagocytic infiltration and progressive collagenous fibrosis. Ductal epithelia may undergo squamous metaplasia (supported by deficient vitamin A resorption). Clinical features are those of malabsorption with abdominal distention, bulky foul stools, and a failure to thrive.

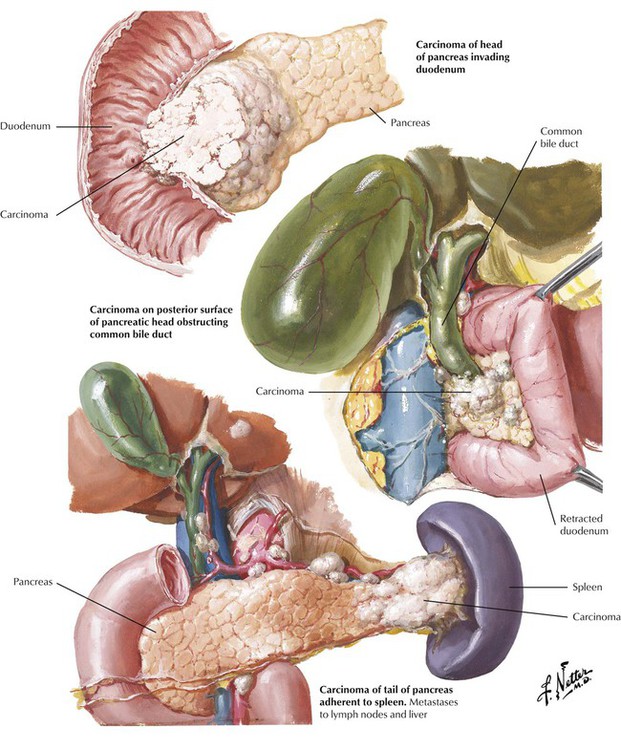

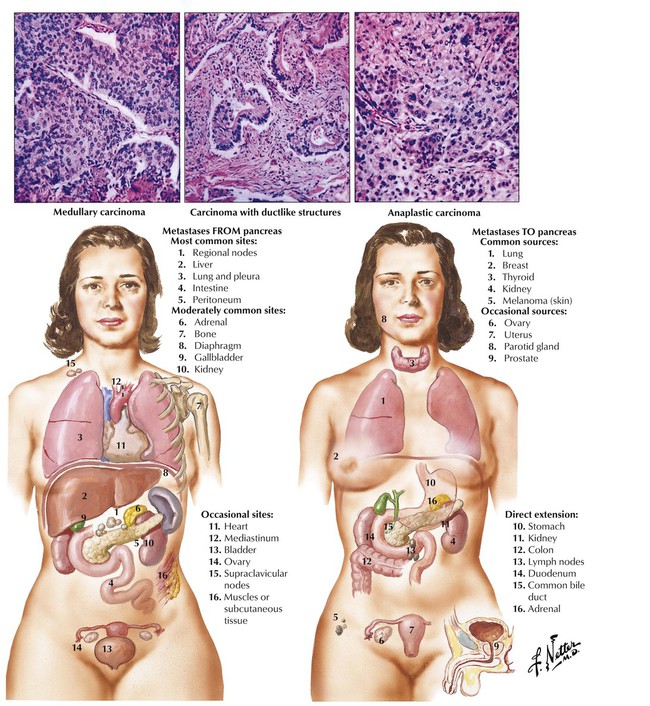

Carcinoma of the pancreas develops from ductal epithelial cells. Approximately 60% of pancreatic cancers are located in the head of the organ, 10% are located in the body, and 5% are located in the tail. The residual tumors show diffuse organ involvement without indication of their initial site. Usually, the tumor has already metastasized at the time of diagnosis. On gross inspection, the carcinoma of pancreas appears as poorly demarcated, white scarred or nodular areas with or without involvement of the common duct, the papilla, or the duodenum. Obstruction of the common bile duct may cause a characteristic dilatation of the gallbladder with jaundice (Courvoisier sign). An important complication of pancreatic cancer is a variable and migrating thrombosis (migratory thrombophlebitis), which may bring patients to clinical attention for multiple pulmonary thromboses and infarcts of unknown origin.

Tumors of the pancreas grow into the adjacent peritoneum and organs (duodenum, stomach, liver, colon, spleen) by direct extension and metastasize most commonly to regional lymph nodes and the liver. Lymphangitic metastases to the lungs and hematogenous spread to the bone marrow (occasionally with fatty necroses) are also found. Most tumors are well-differentiated tubular adenocarcinomas with or without mucin secretion and associated fibrosis (desmoplastic tubular carcinoma).