6 Liver disease

Investigations

Routine serum liver biochemical tests

Box 6.1 shows an interpretation of abnormal liver biochemistry.

Box 6.1 Abnormal liver biochemistry — how to proceed

Always check the history and examine the patient for signs of liver disease.

The role of imaging

US is useful for the detection of gallstones and for evaluation of hepatosplenomegaly and other abdominal masses. In focal liver disease, lesions > 1 cm can be detected and US is used to screen patients for hepatocellular carcinoma. Colour flow Doppler will show the direction of blood flow in the portal and hepatic veins. In endoscopic ultrasound, a small, high-frequency US probe mounted on the tip of the endoscope can accurately stage pancreatic tumours (particularly neuroendocrine) and also chronic pancreatitis.

Liver pathology

Jaundice

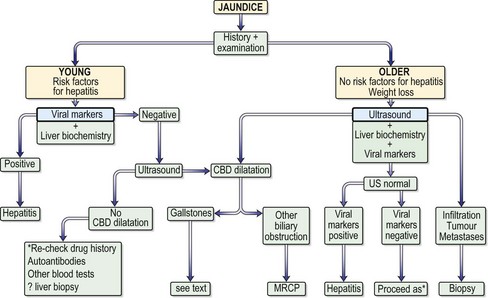

Jaundice (Fig. 6.1) is due to intra- or extrahepatic cholestasis.

Fig. 6.1 Approach to the patient with jaundice. CBD, common bile duct; MRCP, magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography; US, ultrasound.

Approach to the patient

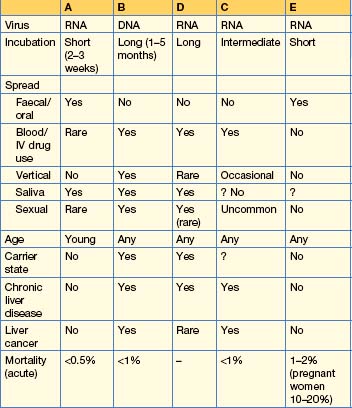

Viral hepatitis

Hepatitis A

Management

Hepatitis B

HBV spread also occurs by the IV route (e.g. by transfusion of infected blood or blood products, or by contaminated needles used by drug users, tattooists or acupuncturists) or by close personal contact, such as during sexual intercourse, particularly in men having sex with men (25% of cases in the USA). The virus can be found in semen and saliva.

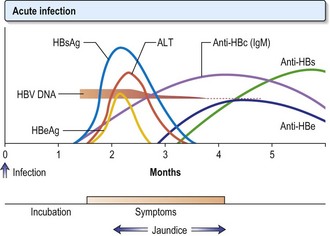

Clinical features

Viral markers

Treatment

HBV infection is mainly asymptomatic and the majority recover completely. Patients should have their HBV markers monitored. If HBcAg is persistent beyond 12 weeks, refer to experts, who may treat patients with nucleoside analogues. Around 1% of patients with acute hepatitis develop fulminant hepatitis (p. 187).

The aim of treatment is the seroconversion of HbeAg (when present), i.e. the development of anti-HBe and the reduction of HBV DNA to undetectable levels by PCR. In addition, normalization of the serum ALT level and histological improvement in inflammation and fibrosis reflects a good response.

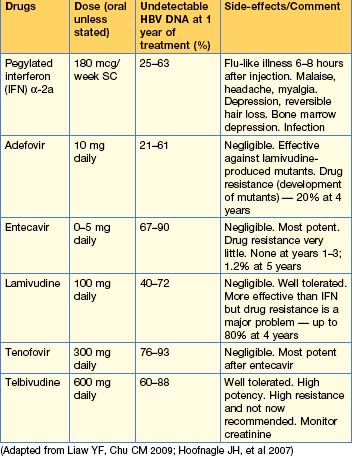

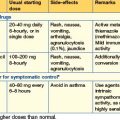

Antiviral agents (Table 6.2)

Choice and duration of treatment

The duration of all treatment, and which combination of antivirals is optimal, are still being assessed. In general, current treatment for HbeAg-positive disease is with pegylated interferon or tenofovir or entecavir. Interferon should be given for 1 year. HbeAg-negative disease requires long-term (many years of) oral therapy. Older patients respond poorly to interferon and should be treated with nucleoside and nucleotide analogues.

Active and passive vaccination for hepatitis B

Widespread vaccination in children is becoming more common. Vaccination is now recommended for all healthcare personnel, persons with multiple sex partners and those seeking treatment for STIs. People with haemophilia and patients with chronic kidney disease on dialysis units should also be vaccinated. A recombinant vaccine is safe and effective. Three injections of 1 mL are given at 0, 1 and 6 months into the deltoid muscle, giving good-term protection in over 90% of patients. A booster dose may be required 3–5 years later.

Hepatitis C

Treatment

Antiviral agents

Current treatment is combination therapy with pegylated interferon, which is interferon with a polyethyleneglycol tail (α2a 180 mcg/week or α2b 1.5 mcg/kg/week) and ribavirin (1000–1200 mg/day for genotype 1, 800 mg/day for genotype 2 or 3) in daily divided doses for 12 months for genotype 1, and 6 months for other genotypes. Efficacy is also determined by viral load, with HCV RNA ≥ 6 000 000 U/L less likely to respond. For the side-effects of interferon, see p. 184. Ribavirin is usually well tolerated but side-effects include a dose-related haemolysis, and pruritus and nasal congestion occur. Pregnancy should be avoided, as ribavirin is teratogenic. Taribavirin is a new alternative with less anaemia being reported.

Fulminant hepatic failure (See Emergencies in medicine p. 708)

Histologically there is multi-acinar necrosis involving a substantial part of the liver. The patient is encephalopathic and jaundiced; gastrointestinal haemorrhage, sepsis, hypoglycaemia and worsening of the encephalopathy occur. Patients require 10% glucose infusion, correction of any coagulopathy (with IV vitamin K, platelets, blood or fresh frozen plasma) and any electrolyte abnormality with potassium, calcium, phosphate and magnesium as appropriate. A proton pump inhibitor should be given intravenously to prevent stress ulcers. Prophylaxis against bacterial and fungal infections is not routine but given if there is advanced encephalopathy, refractory hypotension or the development of SIRS. Suspected infections should be treated with an appropriate antibiotic. Raised intracranial pressure requires 20% mannitol intravenously. Patients should be managed in a specialized unit (Box 6.2), as liver transplantation may be required. Prognostic variables are shown in Box 6.3.

Cirrhosis and its complications

Complications

Variceal haemorrhage

Approximately 90% of patients with cirrhosis will develop gastro-oesophageal varices over 10 years and one-third of these patients will bleed from them. This is discussed in upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage, p. 149.

Ascites

Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (SBP)

Hepatocellular carcinoma

This is one of the ten most common cancers worldwide.

Liver transplantation

Chronic liver disorders

Autoimmune hepatitis

In both groups there may be features of other autoimmune diseases, such as pernicious anaemia, thyroiditis and Coombs-positive haemolytic anaemia.

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC)

Alcoholic liver disease

Alcoholic hepatitis

Hereditary haemochromatosis (HH)

HH is a common inherited disease characterized by excess iron deposition in various organs, leading to eventual fibrosis and functional organ failure. Diabetes, arthritis, hypogonadism and cardiomyopathy are seen; the classic bronzed skin colour is rare. There is hepatomegaly with deranged liver biochemistry.

Diagnosis

Treatment

Wilson’s disease

α1-Antitrypsin deficiency

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Drugs and the liver

The ‘predictability’ of drugs to produce damage can be affected by metabolic events preceding their ingestion. For example, chronic alcohol users may become more susceptible to liver damage because of the enzyme-inducing effects of alcohol, or ill or starving patients may become susceptible because of the depletion of hepatic glutathione produced by starvation. Many other factors, such as environmental or genetic effects, may be involved in determining the ‘susceptibility’ of certain patients to certain drugs.

Hepatic damage

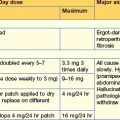

The type of damage produced by various drugs is shown in Table 6.3. The diagnosis of these conditions is usually by exclusion of other causes.

Individual drugs

Czaja AJ, Manns MP. Advances in the diagnosis, pathogenesis, and management of autoimmune hepatitis. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:58-72.

Hoofnagle JH, Doo E, Liang TJ, et al. Management of hepatitis B: summary of a clinical research workshop. Hepatology. 2007;45:1056-1075.

Lange CM, Sarrazin C, Zeuzem S. Review article: specifically targeted antiviral therapy for hepatitis C. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 2010;32:14-28.

Liaw YF, Chu CM. Hepatitis B virus infection. Lancet. 2009;373:582-592.

Lucey MR, Mathurin P, Morgan TR. Alcoholic hepatitis: review. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2758-2769.