Litigation in breast surgery

Introduction

Litigation for clinical negligence has accelerated at an alarming rate. In 2009/10 the NHS paid out £787 m (including £164 m for defence and claimant legal costs).1 In the USA, the value of malpractice claims for delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer 15 years ago was second only to that for neurological damage to neonates2,3 and today this situation remains unchanged.4 Poor cosmetic outcome is also a frequent cause for litigation and heightened public awareness has increased patients’ expectations of recompense for real or perceived injury following both cosmetic and reconstructive breast surgery.

Basic principles

The legal process differs between countries and although this chapter is based on civil law in England and Wales, the general principles in use elsewhere are similar.5 For a claimant to succeed in law, she must satisfy the court (in the UK a judge, or in some countries a jury) that there was a failure or breach of duty of care (liability) and that as a foreseeable result she suffered an injury (causation). For the case to succeed, the court must find in favour of the claimant with regard both to liability and to causation. Clinical negligence cases are heard in civil court and the judge determines on the balance of probabilities whether the defendant is liable. This is entirely different from a criminal court determining guilt or innocence where the level of proof is beyond all reasonable doubt (which many equate to a degree of confidence > 95%). If the court finds in favour of the claimant, the court awards financial recompense to redress, as far as money is able, the injury that she has suffered.

Breach of duty

Any doctor – GP, radiologist, surgeon or pathologist – owes each individual patient a duty of care. This is rarely an issue. In the NHS the doctor acts as an employee of the hospital or health board, which is covered by the NHS Litigation Authority, which administers a scheme that acts as a mutual insurer for participating trusts (Clinical Negligence Scheme for Trusts).6 When acting in a private capacity, the doctor is covered by a professional defence organisation of his or her choice.

The Bolam test

A doctor is not negligent if he or she acts in accordance with a practice accepted at the time as proper by a responsible body of medical opinion. The Bolam test arises from the case of a patient who received electroconvulsive therapy and sustained fractures.7 Negligence was alleged because the patient was not given muscle relaxants and was inadequately restrained. Some doctors would have used muscle relaxants and restraints, others not. The doctor was not found negligent because he acted in accordance with a practice accepted at the time, even though other doctors may have advocated a different practice.

The Bolitho modification of Bolam adds the requirement that for the practice or opinion formed to be acceptable, it must be based on logical argument; an irrational practice cannot be argued as reasonable in court simply because a body of medical opinion agrees with its use.8

Guidelines

National and local guidelines of good clinical practice are now in use throughout the NHS with guidelines covering patient referral, diagnosis, treatment and organisational arrangements within breast units.9,10 Breaches of guidelines are not indicative of, or equivalent to, negligent practice and guidelines are constantly being amended in the light of scientific knowledge, healthcare resources, government targets, etc. Consideration must always be given to the time at which the alleged breach of duty took place and for a guideline to be relevant it must have been in the public domain at the time.

Clinical practice that complies with guidelines is inevitably much easier to defend against allegations of negligence. A diagnostic excision biopsy exceeding 20 g, as set out in NHS Breast Screening Programme guidelines, does not equate to negligent practice; however, a patient claiming excessive deformity after such a procedure is unlikely to succeed in litigation if her biopsy specimen weighed under 20 g. There is ongoing debate regarding the medico-legal implications of surgical guidelines.11 Carrick et al.12 reported that whereas 41% of surgeons surveyed believed that guidelines would protect them against litigation, 37% believed that they would increase their exposure to claims.

Consent

Doctors have been made increasingly aware of the need to warn patients of the risks involved with any diagnostic or therapeutic procedure, to involve patients in decision-making and to seek fully informed consent. Patient information leaflets, involvement of breast-care nurses and more detailed consent forms signed by the operating surgeon are now standard practice but have done little to stem the tide of litigation as expectations continue to rise. Consent obtained by a junior doctor without the knowledge and skill to undertake the intended procedure or to discuss the possible complications is no longer considered acceptable. The degree of disclosure is primarily a matter of clinical judgment, but major complications (such as loss of a flap in breast reconstruction) must be included even if their occurrence is rare.5,13 Where a procedure (such as breast reduction) is being undertaken primarily for cosmetic reasons, the surgeon is advised to include even minor potential consequences in the documentation of informed consent.

The award of damages

The sole remedy available to the successful claimant is an award of damages – a sum of money intended to restore the claimant to the position she would have been in but for the negligent act. Explanation and apology to the claimant or her family, desirable though they may be, are not within the power of civil law, nor are recommendations for retraining, suspension or deregistration of doctors who find themselves as defendants. Patients seeking to hold their doctor to account are, however, increasingly turning to the fitness to practice procedures of the General Medical Council (GMC), with such enquiries rising 30% between 2004 and 2009.14 An unhappy patient may both embark on litigation and report the doctor to the GMC, with the practitioner facing so-called double jeopardy.

In English law the perceived culpability or magnitude of the negligent act has no bearing on the sum awarded. This contrasts with the position in the USA, where cases that proceed to trial (the minority) rely on jury decisions that often incorporate an element of punitive or exemplary damages, a sum the jury considers warranted by the wrongfulness of the defendant’s act. The extent to which this affects the size of the award can be seen by comparing the average value of claims concluded by settlement ($282 000) with that secured by jury verdict ($870 000).3

The Woolf report

In a review of the UK civil justice system, Lord Woolf singled out clinical negligence cases15 because the difficulty in proving both liability and causation accounts for much of the excessive cost and the high proportion of cases that fail. The root of the problem, however, lies less in the complexity of the law than in the climate of defensiveness. The patient’s disappointment when treatment goes wrong is heightened by what she perceives to be a refusal to acknowledge fault and an attempt to cover up.

• Pre-litigation protocol where claimants should notify defendants with a written intention to sue 3 months before action. If liability is disputed, defendants should provide a reasoned answer.

• Lists on the Queen’s Bench to include a list of judges familiar with clinical negligence cases and training of trial judges in medical issues.

• Fast-track options for claims under £10 000 so that these can be litigated on a modest budget with a single expert acceptable to both parties appointed by the court.

• The medical expert is now required to address his report to the court and not to the instructing party,16 with an overriding duty ‘to provide objective unbiased opinion to the court on matters within his expertise, never assuming the role of an advocate’.

The burden (level) of proof

In civil litigation the court determines the facts, which means that the judge makes a decision on the balance of probabilities. This means that the successful claimant will normally recover damages in full, although in one case where the claimant was held to have lost an 80% chance of cure, a deputy high court judge directed that damages should be calculated accordingly.17

The all-or-none nature in awarding damages is arguably the most troubling aspect for experts involved in clinical negligence.18 For example, if the court finds that as a result of negligence a woman has suffered a reduction in her chance of survival from 60% to 40%, she will be awarded the full amount to compensate her (or her family) as though the loss had already occurred, on the basis that on balance she is now more likely to die. If the court finds, however, that her chance of survival has reduced from 90% to 60%, it may award her nothing on the basis that on balance her chance of survival remains unchanged.

Delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer

Delay in diagnosis may occur as a result of failure to refer the patient from primary care or, once referral has taken place, for example with false-negative mammography, failure to perform triple assessment, misinterpretation of equivocal results or the misfiling of a positive test result.19

Litigation arising from delay in diagnosis concerns two main areas:

• Did the delay necessitate more extensive treatment?

• Did the delay in diagnosis reduce the chance of cure?

This is a controversial area since there is public expectation, promoted over the years by health campaigners, that earlier diagnosis offers better chance of a cure. Where expert opinion is divided, the court often prefers the evidence in favour of the delay having caused a reduced survival time. A review of claims for diagnostic delay in breast cancer in Sweden over a 10-year period concluded that delays had an impact on treatment in 23% of cases and adversely affected prognosis in 11% of those patients for whom the delay was longer than 12 months.20

Delay in primary care

The GP who sees many cases with benign breast symptoms each year but only one or two breast cancers is in a difficult position and GPs are increasingly facing litigation for delays in referral. The main area of contention is where long-standing or recurrent breast nodularity coexists with an (initially) undetected lump. Relying on a negative mammogram without an expert clinical examination, ultrasound or needle biopsy may increase the risk of false reassurance.19

GPs today are therefore faced with referring most women with breast symptoms for a specialist opinion and referral guidelines have been in use in the UK since 1995.21–23

Delay after specialist referral

Breast units throughout the UK submit audit data on compliance with 2-week target referrals for suspected cancers.24 The prioritisation of referral letters can be counter-productive if non-urgent cases have to wait longer, but current NHS guidelines stipulate all symptomatic breast referrals are now seen within 2 weeks. NHS ‘31/62’ cancer targets (allowing 31 days from urgent referral to diagnosis and 62 days to commencing treatment) will identify units in breach of national guidelines.

The role of triple assessment, and the circumstances in which it fails, are critical. The specialist centre is also faced with the problem that women under 35 form the majority of the diagnostic workload (66%) but the fewest number of breast cancers (3%).21

The North American experience

Two studies commissioned by the Physician Insurers Association of America (PIAA)2,3 showed delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer to be the commonest cause of clinical litigation, and a striking feature of both studies was young age: women under 50 accounted for 69% of claimants and received 84% of the damages paid, whereas only 25% of cancers occur in women under 50.

The most common reasons cited for the delay were (in descending order):

• physical findings failed to impress;

• failure to follow up the patient;

In 487 cases where liability was admitted, the mean delay was 14 months. The mean payout was $301 000, with higher damages for longer delays and to younger patients.3

Diagnosis of breast cancer

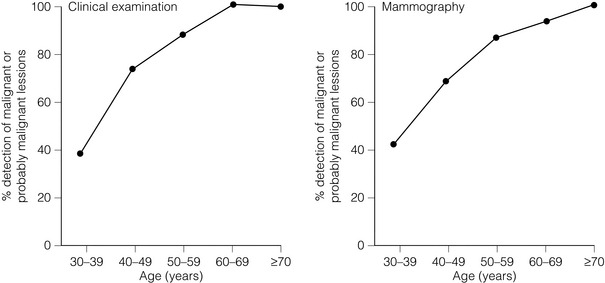

Triple assessment is the foundation upon which clinicians diagnose breast lumps. However, the extent to which the accuracy of these tests is reduced in younger women is not well appreciated (Fig. 18.1). It has been suggested that perfection of diagnosis will require removal of every solid mass,25 but this would represent a retrograde step. The practice of defensive medicine, in place of conventional wisdom, may well be encouraged by a litigious public and diagnostic tests where the sensitivity falls below 95%.

Figure 18.1 Sensitivity of clinical and mammographic examination by age. Reproduced from Dixon JM, Mansel RE. Symptoms, assessment and guidelines for referral. In: Dixon JM (ed.) ABC of breast diseases, 2nd edn. London: BMJ Books, 2000; p. 6. With permission from Wiley Publishing Ltd.

Physical examination

About 70% of all breast cancers are palpable, but with tumours of 0.6–1 cm diameter this figure falls to 50%.26 The larger the breast and the greater the density of breast tissue, the more difficult physical examination becomes. Cyclical changes in breast parenchyma may require repeat examination at different phases of the menstrual cycle. Coexisting benign lumps, scars and distortion from previous surgery, the ridge of tissue above the inframammary fold, changes during pregnancy and lactation, and the underlying ribs all add to the uncertainty of clinical examination. Other difficulties include: inflammatory cancers masquerading as infection; the presence of implants with an associated fibrous capsule; and the effect of hormone replacement therapy, which increases the density of breast parenchyma both clinically and radiologically.

The sensitivity of clinical examination in women aged 30–39 can be as low as 25%.26 A sensitivity over 90% can only be expected in older women, when the atrophic nature of the breast parenchyma and the low incidence of benign disease combine to make clinical diagnosis a relatively simple task. The low sensitivity of clinical examination, coupled with the low incidence of breast cancer and the considerable numbers of young women attending breast clinics, must largely explain why failure of physical findings to impress the clinician was one of the most common reasons for delay in diagnosis in the PIAA study.3

Mammography

False-negative mammography is one of the principal reasons for delay in diagnosis,3,27 since it gives the clinician and patient false reassurance. Age is an important factor in false-negative reporting (Fig. 18.1), with the number of cancers missed inversely proportional to age: 36% of cancers in women aged 40 compared with just 9% in those aged 75. The net result of medicolegal pressure on breast radiologists has been an increase in recall and biopsy rates.28,29

Ultrasound

The use of ultrasound is now an integral part of breast imaging in a patient of any age with a lump (see Chapter 1), especially when an abnormality is not detectable on clinical or mammographic examination. Ultrasound-guided core biopsy has replaced fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) in screen-detected tumours, although both techniques are currently acceptable in the symptomatic clinic. The expertise required for ultrasound examination and guided core biopsy has placed breast imaging outside the competency of the general radiologist. The breast surgeon using ultrasound in the clinic may be similarly compromised unless training in the technique can be verified.

Cytology

For many years FNAC has allowed rapid and cost-effective tissue diagnosis of a palpable lump. How reliable is FNAC? Dixon et al.26 reported that the sensitivity of FNAC could be increased from 66% to 99% by restricting the biopsy to one aspirator. In comparison, the sensitivity of FNAC in women under 36 was as low as 78%,25 though Dixon et al.26 found that accuracy was not related to age if inadequate samples were excluded from the calculations.

In a review of 112 reports of FNAC of breast masses by Layfield et al.30 the overall accuracy was over 95% but delays in diagnosis of greater than 50 days still occurred, and 85% of such delays were in women under 5531 and with smaller tumours.32 In small tumours, a sampling error is probably more common than misinterpretation of the cytology and ultrasound-guided core biopsy is advisable.

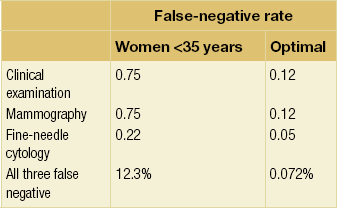

Efficacy of triple assessment

If it is assumed that breast cancer detection by clinical examination, imaging and FNAC are independent of each other, it is possible to calculate the theoretical rate at which all three tests will give a false-negative result. The false-negative rates of the three investigations have been multiplied and expressed as a percentage in Table 18.1. It is probable that the sensitivities of these tests are not totally independent of each other, and therefore the predicted rate that all three tests will be false negative for an individual is a conservative estimate. For a woman under 35 with breast cancer, there may be a 12% chance that all three tests will give a false-negative result. Using optimal sensitivities, the chance that all three tests will produce a false-negative result falls to approximately 1 in 1000 patients with these data skewed towards the older age groups; the likely overall rate of false-negative triple assessment in the clinic is between 1.4% and 4%.32,33

Tumour doubling time

Assuming a constant doubling time, early detection of breast cancer is a misnomer, since at least two-thirds of the biological life of the tumour will have been completed by the time of detection.34 In medicolegal terms, if the alleged delay in diagnosis was 14 months for a cancer with a doubling time of 90 days, such a delay would equate to the number of cells increasing by one order of magnitude (i.e. from 109 to 1010 cells). This represents a major increase in tumour load but is a very short period in the lifespan of the tumour and it is difficult to be sure that this period of delay would have a significant effect. In civil law, however, the court wants to know whether such an effect is more likely than not to alter the patient’s prognosis or treatment.

Lymph node status remains the most important prognostic indicator at the time of primary treatment. Tubiana and Koscielny35 suggested that breast cancer represents a continuum from slow-growing tumours with late axillary involvement and distant dissemination to the most aggressive, rapidly growing and early metastasising subtype. Assuming the growth rate of the nodal metastasis approximates to that of the primary tumour, it is possible to estimate the theoretical time at which the tumour must have metastasised, and not infrequently this would have occurred before the threshold size for detection of the primary tumour.34

It is generally accepted that breast cancer begins as a single cell or a small group of cells that exhibit an exponential growth pattern. The time taken for a tumour to double in volume is known as the doubling time. Doubling times for breast cancers have been estimated by measuring the size of mastectomy scar recurrences36 and by serial mammographic evaluation.37

Pearlman36 categorised patients as having fast- (< 25 days), intermediate- (26–75 days) and slow-growing (> 76 days) tumours based on measurement of tumour doubling time; 5-year survival rates were 5%, 62% and 100% respectively. Peer et al.38 estimated mean doubling time in women under 50 to be 80 days (confidence limits 44–147 days) and in women over 50 to be 157 days (confidence limits 121–204 days). Although lymph node metastases are more commonly found in fast-growing tumours, it would be wrong to assume that the survival of patients was entirely a consequence of tumour doubling time. Galante et al.37 emphasised the importance of the metastatic potential of the tumour, suggesting that within fast-, intermediate- and slow-growing tumours there may be subsets with high and low metastasising potential.

The premise that early detection of a tumour will lead to cure depends on the concept that at the time of earlier treatment the tumour has not metastasised. The period of time between the earliest possible detection of the cancer and the time at which the tumour metastasises has been described as the cancer control window.39 If the tumour has already metastasised by the time it reaches the threshold size for detection, there is no window and only effective systemic therapy might cure the patient. It is often argued by the claimant and her legal team that delay in treatment is the cause of metastasis rather than the inherent biology of the tumour itself.

Vignettes on breach of duty

Vignette 1: False-positive cytology, lymphoedema and alteration of records

Comments

• A false-positive cytology result is a rare but potentially devastating event. From a medico-legal standpoint, an expert review of the cytology should be the first step. If experts are agreed that the cytologist acted reasonably in reporting the slides as malignant, attention will then focus on the surgeon.

• The surgeon has to be aware that a false-positive cytology can occur and for this reason most surgeons will not carry out mastectomy without histological confirmation from a core biopsy. Histology is mandatory in the absence of a fully concordant malignant triple assessment and should have been obtained in this case. Axillary clearance for a benign condition is a potentially significant injury and it is unfortunate that this patient developed lymphoedema.

• The tense of the warning suggested to the judge that this was a retrospective note. Judges place most reliance on contemporaneous records and alterations to the notes are often quite obvious. Any addition to the notes must be clearly identified as such by signing and dating the record and any temptation to alter the record after the event must be firmly resisted.

Vignette 2: Failure of preoperative assessment and postoperative management

Comments

• The management of this patient falls short of an acceptable standard in a number of respects (breach of duty), but until such time as she develops evidence of recurrence, which may never occur, any resultant harm (causation) remains potential.

• A preoperative mammogram might have shown widespread microcalcification or multifocal tumour and in this situation conservative surgery would not have been appropriate. There might also have been an undetected cancer in the contralateral breast.

• To fail to report the margin status and managing a patient with conservative surgery without consideration of radiotherapy is unacceptable.

• It is clear that this case was not discussed at a multidisciplinary meeting.

• Axillary node status should have been assessed and has been recommended in UK guidelines since 1995.9

Vignette 3: False-negative cytology, trainees in the clinic and lobular carcinoma

Comments

• Trainees must be adequately supervised and only permitted to see patients by themselves when their trainer is satisfied that they are competent and understand local protocols.10

• There is a learning curve in achieving adequate samples with FNAC. The rate of inadequate FNAC samples should be monitored for each clinician.

• Clinicians should be aware that lobular cancers are prone to false-negative mammography. There is also an increased difficulty with false-negative cytology interpretation.

• The diagnosis of breast cancer in young women is difficult and in the situation where a patient complains of a lump but on clinical examination or mammography nothing is obvious, ultrasound is advisable, with guided biopsy if a lesion is seen.

Vignette 4: Pneumothorax following FNAC

Comments

• Did the clinician fail in his duty of care by advancing the needle too far or by failing to warn the patient? The literature suggests a risk of around 1 in 10 000.40–42 It is not rare to strike a rib with the needle at FNAC. Piercing the pleura may be more common because a trivial pneumothorax may go undetected.

• In several cases the court has found pneumothorax to be a rare but recognised complication that can occur without breach of duty, although one case ruled this injury to be negligent, which was an unexpected judgment.42 There is often a reluctance on the part of trusts to defend or appeal low-value cases under £10 000 (as would be the case for damages here).

• In defending a claim of negligence, it is important to be able to show that the clinician was experienced in the technique. Were this to be a trainee, it would be necessary to establish that he or she had been properly supervised.

• Pneumothorax has been reported following needle localisation by a radiologist and following aspiration of axillary seroma, performing FNAC and core biopsy. Using image guidance should theoretically reduce the risk.

Delay in diagnosis: causation issues

Having established breach of duty, the issue of causation may include the allegation that less treatment would have been required. It may also be argued that psychological damage has ensued. However, the main issue centres around whether the claimant has suffered a reduced expectation of life or, if she has died by the time the matter comes to court, whether she would have lived longer. Richards et al.,43 after a systematic review, concluded that there is an average reduction in 5-year survival of 7% with a delay of 3–6 months and 12% with a delay of more than 6 months. Dische et al.44 extrapolated a 1.8% decrease in survival from Richards et al.’s data for each 1-month delay up to 6 months. In the same issue of the Lancet, Sainsbury et al.45 reported no such effect but produced the apparently contradictory finding that patients with the shortest delay had the worst prognosis, a finding previously reported by Afzelius et al.46

The survival in patients with the best-prognosis tumours (small, special type, grade 1, node negative) approaches that of the normal population, and clearly a formula attributing a reduction in survival for each month of delay would be inappropriate in such tumours. However, if one accepts this, then for some tumours with a worse prognosis there must be a greater loss of survival.44 It would nevertheless seem intuitive that the most aggressive tumours with rapid metastatic potential are likely to be incurable from early in their natural history, suggesting diagnostic delays in such cancers are less likely to have an impact on survival.

Vignettes on causation

Vignette 5: 12-month delay in diagnosis of node-positive carcinoma

Comments

• The Nottingham Prognostic Index (NPI)47–49 and Adjuvant!Online50 are often used to determine the difference in outcome over the period of delay.

• Both NPI and Adjuvant!Online rely on the following assumptions about the individual case:

Assumption 1: the tumour grade remains constant – this is usually agreed by both sides.

Assumption 2: earlier tumour size. In this particular case a record of tumour size at the first visit was available, but if no clinical measurement was recorded and there was no imaging, an approximate tumour size has to be derived by working back from the tumour volume at diagnosis using tumour doubling times. This calculation assumes (i) that tumour growth is exponential, (ii) that in calculating tumour diameter the tumour approximates a sphere or an ellipsoid, and (iii) that the doubling time chosen is appropriate. Tumour size itself is a weak determinant of prognosis but the derived earlier tumour size is further used to calculate the likely nodal status.

Assumption 3: the nodal status at the time of the breach of duty is usually unknown and often disputed by the experts. Axillary node status is invariably presumed to have been negative by the claimant, and this claim is supported by tables for tumour grade and tumour size that show the probability of positive nodes.51 Only in grade 2 and 3 tumours greater than 2.5 cm does the probability of positive nodes rise above 50%. Therefore, on balance it may often be argued that the nodes would have been negative at the earlier time when the tumour was smaller.

Vignette 6: 2-year delay in diagnosis of node-negative grade 1 carcinoma

Comments

• The standard of care must be judged against the standard reasonably to be expected of a cytologist working at the same level and not that of a world expert in the field.

• Although the tumour doubled in diameter over the 2-year period of delay, it remained within the good prognosis group. The treatment would have been the same with an earlier diagnosis and therefore the case did not succeed on causation.

Vignette 7: 3-year delay in diagnosis of a carcinoma missed on screening

Comments

• Delay due to radiological misinterpretation tends to be a matter of years rather than months. Screening by 3-yearly mammography probably reduces breast cancer deaths by up to 25%, and it is likely that a delay in diagnosis of 3 years will affect survival in a proportion of cases.

• The potential loss of survival in this case would be considerable since the original lesion would, on the balance of probabilities, have been an area of high-grade DCIS with a near-normal expectation of life if adequately treated at age 50. At age 53 the patient now has a relatively poor prognosis but on balance is still more likely to survive 10 years (Table 18.2).

Table 18.2

Nottingham Prognostic Index groups

| Group | NPI value | 10-year survival (%) |

| Excellent (EPG) | 2.0–2.4 | 96 |

| Good (GPG) | 2.41–3.4 | 93 |

| Moderate I (MPGI) | 3.41–4.4 | 82 |

| Moderate II (MPGII) | 4.41–5.4 | 75 |

| Poor (PPG) | 5.41–6.4 | 53 |

| Very poor (VPG) | ≥ 6.41 | 39 |

From the Nottingham Primary Breast Cancer Series. Data relate to patients with primary operable breast cancer, treated from 1990 to 1996.47

Vignette 8: 14-month delay in the breast clinic and failure to recommend chemotherapy

Comments

• Discussion of the discordant triple assessment at the breast multidisciplinary meeting (MDM) did not take place.

• Arranging a 6-month follow-up for a breast lump that is presumed benign is illogical.

• The judge took evidence from five expert witnesses. It was agreed that when first seen the tumour would have been grade 3, 1 cm in diameter and node negative. The tumour had increased in size to 4 cm in the 14 months of delay and opinion was divided as to whether this was ever potentially curable. The experts for the claimant were far more optimistic than those for the defence but in the event the judge preferred the latter.52

• The judge considered that, on balance, the breach of duty ‘caused her to die 18 months before, sadly, she would have died anyway’.

• Unfortunately, the damages amounted to less than the defence had already paid into court. Civil litigation rules resulted in the family winning the case but receiving none of the settlement.

Vignette 9: 8-month delay in diagnosis in primary care

Comments

• Following an opinion from a GP expert, breach of duty on the part of the GP was admitted and the claim for causation was both for more extensive treatment and loss of chance of survival.

• The claimant’s breast expert maintained that she would had undergone wide excision and sentinel node biopsy at the earlier time and that her expected survival had been reduced from 93% to 53%.

• At a pre-trial meeting of experts, they agreed jointly that the nodes would still have been involved at the earlier time and that the axillary surgery would have been unchanged, and agreed that she was, on balance, still more likely to survive than die from the breast cancer.

• The experts agreed that she had lost the chance of breast conservation as a result of the delay and following their joint report the case was settled for £50 000 on the basis that she had undergone mastectomy and would require future breast reconstruction.

• Less than 5% of clinical negligence cases are contested in court with over 95% of cases either dropped or settled before the trial date.

• Since the discussion of discordant triple assessments in breast MDMs has become widespread good practice, claims for delay in diagnosis against breast specialists have reduced and are now mainly against GPs who fail to refer cases to the breast clinic.

Poor cosmetic outcome

The mastectomy rate in the UK remains close to 40%, and where mastectomy is required the increasing demand for reconstruction has been addressed in national guidelines53 and detailed audit.54 Litigation has risen in line with patients’ expectations,55 although the typical size of claim for an unsatisfactory cosmetic outcome is considerably less than for delay in diagnosis.

Should a patient pursue litigation for her cosmetic outcome, the Bolam principle7 would apply in determining breach of duty, i.e. the practice would be compared with that held to be reasonable by a similar body of professionals, in this case breast surgeons trained to undertake breast reconstruction. An audit of the surgeon’s operative results is not currently expected by the court, nor are there prescribed minimum numbers of procedures to comply with good practice. At present there is no certificate of competency in training in breast reconstruction within the UK, but current reconstructive guidelines53 outline the requirements for good practice.

Reduction mammoplasty, breast augmentation and surgery for gynaecomastia remain high-risk areas for patient dissatisfaction and should never be undertaken on an occasional basis. Breast operations represent the biggest group of plastic surgical procedures giving rise to claims.56 It is vital that evidence of appropriate discussions about potential problems is adequately recorded in the notes and the correspondence, together with the use of appropriate information leaflets and clinical photographs to explain the proposed procedure. Consent forms should record the signed informed consent as well as documenting that the literature has been received and understood. Operation notes, where relevant, should include details of implant type, serial and lot number, and manufacturer, for possible future reference.57

Vignette 10: Poor cosmetic outcome after immediate breast reconstruction

Comments

• With cosmetic and reconstructive surgery, the damage is self-evident, i.e. causation is less of an issue than breach of duty. With delay in diagnosis the converse is often the case.

• Patient expectation of a good cosmetic outcome is arguably less demanding for postmastectomy reconstruction than for purely cosmetic surgery of the breast. Nevertheless, there is growing demand for a wider choice and more sophisticated reconstruction techniques.

• The first question that must be addressed is the adequacy of training in reconstructive surgery. If the level of training was appropriate, the second question is whether the standard of advice and operative skill met that which the patient could reasonably have expected. Unless the answer to both questions is in the affirmative, the surgeon is liable.

• Most breast surgeons undertaking reconstruction in the UK have attended training courses on the use of subpectoral and latissimus dorsi techniques. Some breast surgeons undertake pedicled transverse rectus abdominis muscle reconstruction, but free tissue transfer is beyond the training and theatre time constraints of most breast surgeons.

References

1. Lawyers’ fees and NHS savings. Br Med J. 2011; 343:d4035–d4036.

2. Physician Insurers Association of America. Breast cancer study. Rockville, MD: PIAA; 1990.

3. Physician Insurers Association of America. Breast cancer study. Rockville, MD: PIAA; 1995. [p. 1–27].

4. Physician Insurers Association of America. Claim trend analysis, 2011 ed. Rockville, MD: PIAA; 2011.

5. Branthwaite, M. Law for doctors: principles and practicalities. London: Royal Society of Medicine Press; 2000.

6. NHS Litigation Authority. Available at http://www.justice.gov.uk/courts/procedure-rules/civil/rules/part35; [accessed 30.06.12].

7. Bolam v. Friern Hospital Management Committee [1957] 2 All ER 118; [1957] 1 WLR 582.

8. Bolitho v. City & Hackney Health Authority [1997] 4 All ER 771; [1997] 3 WLR 1151.

9. Breast Surgeons Group of the British Association of Surgical Oncology, Guidelines for surgeons in the management of symptomatic breast disease in the United Kingdom. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1995;21(Suppl. A):1–13. 7589617

10. The Association of Breast Surgery at BASO, Guidelines for the management of symptomatic breast disease. Eur J Surg Oncol 2005; 31:1–21. 15862705

11. Hurwitz, B., Clinical guidelines and the law. Br Med J 1995; 311:1517–1518. 8520379

12. Carrick, S.E., Bonevski, B., Redman, S., et al, Surgeons’ opinions about the NMRC clinical practice guidelines for the management of early breast cancer. Med J Aust 1998; 169:300–305. 9785524

13. Chester v. Afshar [2004] UKHL 41.

14. GMC 2009 annual statistics: fitness to practise. Available at http://www.gmc-uk.org; Annual.statistics.pdf.33097340.pdf; [accessed 30.06.12].

15. Woolf, H.K. Medical negligence. In: Access to justice: final report to the Lord Chancellor on the civil justice system in England and Wales. London: HMSO; 1996:169–196.

16. Civil Procedure Rules. Available at www.justice.gov.uk/courts/procedure-rules/civil/rules/part35

17. Brahams, D., Loss of chance of survival. Lancet 1996; 348:1604. 8961988

18. Davidson, T., The medico-legal issue of causation – current status Available at. Association of Breast Surgery at BASO Yearbook, 2006.. http://www.associationofbreastsurgery.org.uk [[accessed 30.06.12]].

19. Salih, A., Webb, M.W., Bates, T., Does open-access mammography and ultrasound delay the diagnosis of breast cancer? Breast 1999; 8:129–132. 14965729

20. Hafstrom, L., Johansson, H., Ahlberg, J., Diagnostic delay of breast cancer – an analysis of claims to Swedish Board of Malpractice. Breast 2011; 20:539–542. 21764312

21. Andrews, B.T., Bates, T., Delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer: medico-legal implications. Breast 2000; 9:223–227. 14731999

22. Davidson, T. Delay in diagnosing breast cancer: medicolegal implications. Trends Urol Gynaecol Sexual Health. 1998; 3:11–12.

23. Austoker, J., Mansel, R., Baum, M., et al. Guidelines for referral of patients with breast problems. Sheffield: NHS Breast Screening Programme; 1995.

24. Dr Foster guide to hospitals and consultants. Available at http://www.drfosterhealth.co.uk

25. Yelland, A., Graham, M.D., Trott, P.A., et al, Diagnosing breast carcinoma in young women. Br Med J 1991; 302:618–620. 2012873

26. Dixon, J.M., Anderson, T.J., Lamb, J., et al, Fine needle aspiration cytology, in relationship to clinical examination and mammography in the diagnosis of a solid breast mass. Br J Surg 1984; 71:593–596. 6743977

27. Joensuu, H., Asola, R., Holli, K., et al, Delayed diagnosis and large size of breast cancer after a false negative mammogram. Eur J Cancer 1994; 30A:1299–1302. 7999417

28. Elmore, J.G., Taplin, S.H., Barlow, W.E., et al, Does litigation influence medical practice? The influence of community radiologists’ medical malpractice perceptions and experience on screening mammography. Radiology. 2005;236(1):37–46. 15987961

29. Halpin, S.F., Medico-legal claims against English radiologists: 1995–2006. Br J Radiol. 2009;82(984):982–988. 19470570

30. Layfield, L.J., Glasgow, B.J., Cramer, H., Fine needle aspiration in the management of breast masses. Pathol Annu 1989; 24:23–62. 2671883

31. Bates, A.T., Bates, T., Hastrich, D.J., et al, Delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer: the effect of the introduction of fine needle aspiration cytology to a breast clinic. Eur J Surg Oncol 1992; 18:433–437. 1426292

32. Jenner, D.C., Middleton, A., Webb, W.M., et al, Inhospital delay in the diagnosis of breast cancer. Br J Surg 2000; 87:914–919. 10931028

33. Barber, M.D., Jack, W., Dixon, J.M., Diagnostic delay in breast cancer. Br J Surg. 2004;91(1):49–53. 14716793

34. Plotkin, D., Blankenberg, F., Breast cancer: biology and malpractice. Am J Clin Oncol 1991; 14:254–266. 2031514

35. Tubiana, M., Koscielny, S., Cell kinetics, growth rate and the natural history of breast cancer. The Heuson Memorial Lecture. Eur J Clin Oncol 1988; 24:9–14. 3338491

36. Pearlman, A.W., Breast cancer: influence of growth rate on prognosis and treatment evaluation. A study based on mastectomy scar recurrences. Cancer 1976; 38:1826–1833. 991096

37. Galante, E., Gallus, G., Guzzon, A., et al, Growth rate of primary breast cancer and prognosis: observations on a 3- to 7-year follow up in 180 breast cancers. Br J Cancer 1986; 54:833–836. 3801276

38. Peer, P.G., van Dijk, J.A., Hedriks, J.H., et al, Age-dependent growth rate of breast cancer. Cancer 1993; 71:3547–3551. 8490903

39. Spratt, J.S., Spratt, S.W., Medical and legal implications of screening and follow-up procedures for breast cancer. Cancer 1990; 66:1351–1362. 2205365

40. Christie, R., Bates, T. The risk of pneumothorax as a complication of diagnostic fine needle aspiration or therapeutic needling of the breast: should the patient be warned? Breast. 1999; 8:98–99.

41. Gately, C.A., Maddox, P.R., Mansel, R.E., Pneumothorax: a complication of fine needle aspiration of the breast. Br Med J 1991; 303:627–628. 1932905

42. Bates, T., Davidson, T., Mansel, R., Litigation for pneumothorax as a complication of fine-needle aspiration of the breast. Br J Surg 2002; 89:134–137. 11856124

43. Richards, M.A., Westcombe, A.M., Love, S.B., et al, Influence of delay on survival in patients with breast cancer: a systematic review. Lancet 1999; 353:1119–1126. 10209974

44. Dische, S., Bentzen, G., Bond, S. The influence of delay in diagnosis of breast cancer upon outlook. Clin Risk. 2000; 6:4–6.

45. Sainsbury, R., Johnston, C., Haward, B., Effect on survival of delays in referral of patients with breast-cancer symptoms: a retrospective analysis. Lancet 1999; 353:1132–1135. 10209976

46. Afzelius, P., Zedeler, K., Sommer, H., et al, Patients’ and doctors’ delay in primary breast cancer. Acta Oncol 1994; 33:345–351. 8018364

47. Thompson, A.M., Pinder, S.E. Prognostic factors. In: Dixon J.M., ed. The ABC of breast diseases. 3rd ed. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing; 2006:77–80.

48. Blamey, R.W., Ellis, I.O., Pinder, S.E., et al, Survival of invasive breast cancer according to the Nottingham Prognostic Index in cases diagnosed in 1990–1999. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(10):1548–1555. 17321736

49. Blamey, R.W., Pinder, S.E., Ball, G.R., et al, Reading the prognosis of the individual with breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(10):1545–1547. 17320376

50. Adjuvant!Online. Available at hppt//:www.adjuvantonline.com; [accessed 30.06.12].

51. Yiangou, C., Shousha, S., Sinnett, H.D., Primary tumour characteristics and axillary lymph node status in breast cancer. Br J Cancer 1999; 80:1974–1978. 10471048

52. Taylor v. West Kent Health Authority [1997] 8 Med LR 251–7.

53. Association of Breast Surgery at BASO; Association of Breast Surgery at BAPRAS; Training Interface Group in Breast SurgeryBaildam, A., Bishop, H., Boland, G., Oncoplastic breast surgery – A guide to good practice. Eur J Surg Oncol 2007; 33:S1–23. 17604938

54. National Mastectomy and Breast Reconstruction Audit (Fouth Annual Report). Available at www.ic.nhs.uk/mbrreports, 2011. [[accessed 30.06.12]].

55. Richards, E., Vijh, R., Analysis of malpractice claims in breast care for poor cosmetic outcome. Breast 2011; 20:225–228. 21232957

56. Claims analysis. MDU J. 2011; 27(2):19–21.

57. O’Dowd, A., UK launches rapid inquiry into the safety of PIP breast implants. Br Med J 2012; 344:e11. 22214894