5 Lithium and long-term prophylactic treatment

LITHIUM

5.4 How effective is lithium?

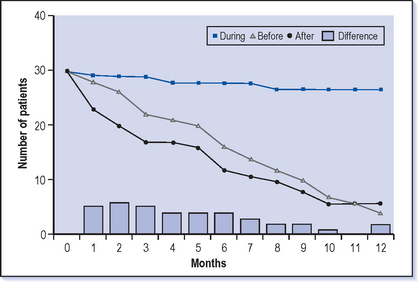

The more statistical view of group effects is that lithium will reduce the rate of relapse by 20-30% (Fig. 5.1). The relapse rates in most trials are about 50% over a year on placebo and this is reduced to about 30% on lithium. However, it is difficult to translate this figure to individuals.

5.5 What are the indications for lithium treatment?

Lithium is occasionally prescribed for certain forms of headache (e.g. cluster headaches).

5.6 Who should be taking long-term preventive treatment for bipolar disorder?

If someone has had even a single, severe, highly disruptive episode of mania or severe depression then it is tempting to suggest that they should take long-term treatment and indeed a few patients do this. However, after one episode it is very uncertain when the next episode will occur (though it almost certainly will occur at some time, see Q 2.18) and most people will not want to undertake a very long-term treatment at this stage.

5.9 How dangerous is it?

However, when the levels are kept below 1.2 mmol/l then lithium is very unlikely to cause long-term harmful effects on either the brain or the kidney. Usually those that suffer from toxicity do so because the levels have slowly gone up rather than in an acute overdose. Although lithium is obviously known to be dangerous at high levels it is surprising how rare overdoses of lithium seem to be, especially given that it is prescribed to a group that is exceptionally vulnerable to suicide (see Q 5.26). This may be because it is a very effective treatment and also that it may have a specific antisuicidal effect. However, the most serious adverse effects of lithium toxicity do seem to occur among those who deliberately take a large overdose of slow release tablets where the levels continue to rise long after ingestion even if they have vomitted.

5.10 What are the symptoms of lithium toxicity?

Levels can reach as high as 5.0 mmol/l and fatalities and permanent physical damage can be expected.

5.12 What needs to be done prior to initiating lithium treatment?

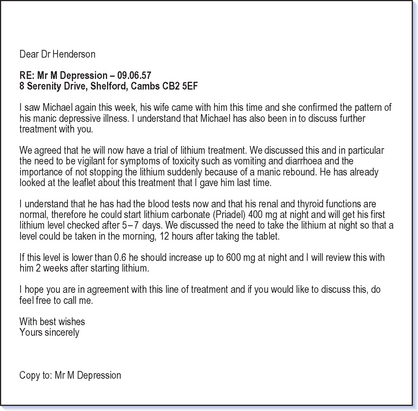

Ensure that the patient has been given a leaflet outlining lithium treatment (see model in Appendix 3) as they will not remember enough from a conversation. Stress the symptoms of toxicity that need to be recognised, and also that careful use of lithium and good monitoring will prevent toxicity occurring. An example of specific instructions from the hospital about how to start treatment are shown in Figure 5.2.

Fig. 5.2 Example of a letter from a consultant to both GP and patient about starting lithium treatment.

The other important piece of information the patient should know is that this is a long-term treatment and sudden cessation of lithium can lead to rebound mania and so a worsening of the illness course (see Q 5.27). This means that the illness can be made worse by taking lithium intermittently than it would have been if the patient had never taken the treatment at all!

5.13 How is lithium treatment initiated?

Assuming that preliminary checks have been made (see Q 5.12) and renal function is normal, the usual routine for beginning lithium treatment would be to start at 400 mg at night and then check a blood lithium level at 5 days. It is likely that the initial target blood level will be 0.6 mmol/l and benefit will be judged at this level. If the blood level at 5 days comes back at less than 0.6 mmol/l the lithium dosage should be increased by 200 mg and checked again at 5 days. This process should be repeated until the desired level is reached. When a stable dose has been reached, continue to monitor every 2 weeks for 1 month, then monthly for a further 3 months and 3-monthly thereafter.

5.14 Why is lithium usually prescribed to be taken all at night?

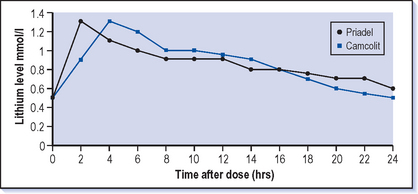

There is no good therapeutic reason for taking lithium at night–it is no more effective then than if taken at any other time. However, side-effects are generally more prominent at higher blood levels which tend to be in the first few hours after taking the tablet (see Fig. 5.3), so it can be preferable for the patient to be asleep at this time. For compliance reasons taking tablets once a day is usually better (see Q 5.43).

5.16 What monitoring needs to take place while on lithium treatment?

When the patient is on a stable dose of lithium, checking lithium levels every 3 months is adequate; checking renal and thyroid function every year is also needed. Weight gain can be a problem with lithium and keeping an eye on this from the start rather than waiting until the patient has gained weight is worthwhile. There have been reports of hyperparathyroidism with lithium and some advocate checking calcium levels annually as well (Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin 1999).

5.18 What blood levels should I be aiming for?

The therapeutic range that is routinely aimed for is 0.4-0.8 mmol/l in the serum at 12 hours after the last dose (Fig. 5.3). When lithium was first introduced into psychiatry, higher levels of up to 1.2 mmol/l were commonly used but over the years the level aimed for has tended to be lower. This is probably because doctors have become more concerned about toxicity, even though with care higher levels can be maintained safely.

Levels need to be at least 0.4 mmol/l in order for lithium to be an effective treatment, and no patient should be maintained below 0.4 mmol/l. Even levels of 0.4 mmol/l may not be enough and the usual practice would be to aim for a level of between 0.6 and 0.8 mmol/l. If this is not well tolerated a trial at lower levels down to 0.4 mmol/l is reasonable. If lithium is well tolerated at levels between 0.6 and 0.8 mmol/l but is only partially relieving or preventing symptoms, then higher levels up to 1.0 mmol/l (or even up to 1.2 mmol/l in acute treatment) may be needed and can be safely used with appropriate monitoring.

5.19 How should I react to a high blood lithium level?

![]() If a lithium level comes back between 1.0 and 2.0 mmol/l it is important to consider the possible reasons for this and to ascertain the patient’s physical and mental state. Often higher readings come back because the blood sample has been taken less than 12 hours after the last dose (see Fig. 5.3). This may be because the patient is taking the lithium in the morning and has had a blood test only a few hours later. It is important to establish first whether this might be the case.

If a lithium level comes back between 1.0 and 2.0 mmol/l it is important to consider the possible reasons for this and to ascertain the patient’s physical and mental state. Often higher readings come back because the blood sample has been taken less than 12 hours after the last dose (see Fig. 5.3). This may be because the patient is taking the lithium in the morning and has had a blood test only a few hours later. It is important to establish first whether this might be the case.

Overall, the level of symptoms, together with the clinical assessment, is more important than the blood levels. It is easy to keep changing the lithium dose frequently in response to blood levels but then to find it difficult to reach a stable dose. It is generally better to re-check levels rather than changing doses if there are no symptoms of toxicity. Dose changes in long-term treatment should be made only if two or three levels indicate the need for this (see Case vignette 5.1) unless there are symptoms of toxicity or the clinical state requires it.

5.20 How should levels above the usual therapeutic range be dealt with?

5.23 What is the management for a bipolar woman who has been successfully treated with lithium but now wants to become pregnant?

5.25 For how long should a bipolar patient continue to take lithium?

The first goal of any long-term treatment is to judge whether the drug is acceptable. Some patients are particularly sensitive to lithium and cannot take it even at therapeutic levels. For example a female bipolar patient found that she was getting diarrhoea even at levels of 0.4 mmol/l and so could not continue with a trial of treatment for longer than a month.

Statistically the time needed to prevent a relapse is 1-2 years so that patients who take lithium for a shorter period may be getting no benefit from it and if they stop it suddenly may well be making their illness worse through rebound effects. Taking the treatment for 6 months and suddenly stopping may mean that the illness course is worse than never having taken it at all. (see Q 5.27).

CASE VIGNETTE 5.2 STOPPING LITHIUM SUDDENLY

CASE VIGNETTE 5.2 STOPPING LITHIUM SUDDENLY

Peter was ill as a student (probably mania followed by depression), reading law at university. His father took him away for an extended holiday in Spain where he built walls, as Churchill had recommended. He got back to university and then qualified as a barrister. He had been brought up abroad and returned to Uganda to work and built up a sound legal practice. However, the arrival of Idi Amin put paid to that and he returned to England in a very depressed state from which he took a year to recover. He then worked in the Caribbean as a government lawyer for 10 years but this ended when he became manic, spent all his savings on yachts and was sacked. A further period of depression back home in England with family followed and he then moved to Australia. This was the first time that he had been prescribed lithium and his wife ensured that he took it every night. He worked successfully for 15 years and restored his affluent lifestyle. He had a talk with his doctor about the lithium and they both decided that he had been well for a long time and could reasonably give it up now. Within a month he had redecorated and re-carpeted his office in yellow. He attended court, not in his usual sober suit, but in a tee-shirt with a cork hanging hat. He was quickly suspended and flew off to Penang first class to gamble, drink and carouse. He was arrested and deported for not paying his hotel bill. On return to Australia he was committed to hospital, for which he never forgave his wife and they separated. He lost his job, his home and his wife and still lives in a hostel near the beach–he has started to take the lithium again.

5.26 Does lithium really reduce the rate of suicide?

There are two reasons why we think that lithium prevents suicides:

5.27 Does stopping lithium suddenly lead to relapse?

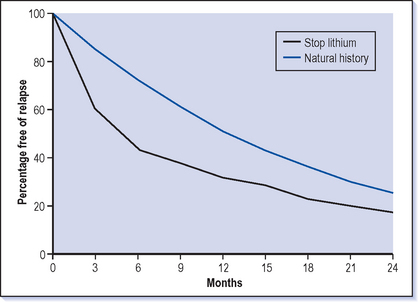

![]() Probably the best way to make bipolar patients manic is to treat them with lithium for a few months then suddenly stop it. About a third of patients will relapse, usually into mania rather than depression, in the following few weeks (Fig. 5.4). This is a rebound effect in that patients do not return to the underlying natural history of manic depression but ‘rebound’ beyond this to a much higher chance of recurrence.

Probably the best way to make bipolar patients manic is to treat them with lithium for a few months then suddenly stop it. About a third of patients will relapse, usually into mania rather than depression, in the following few weeks (Fig. 5.4). This is a rebound effect in that patients do not return to the underlying natural history of manic depression but ‘rebound’ beyond this to a much higher chance of recurrence.

If lithium is stopped gradually over 4-6 weeks then the risk of relapse is less than with sudden cessation and patients return to the risk associated with the natural history and avoid the rebound. However, many doctors would stop the treatment even more slowly, so that any emerging symptoms can be responded to by increasing the dose of lithium again.

5.28 If the patient stops lithium and suffers a relapse, does it work as well the second time around?

There has been concern that the effect of lithium is reduced when it has been stopped suddenly and a relapse has occurred. This is a difficult question to answer as we know that the more episodes a patient has, and the shorter the well interval, the worse the prognosis. If a patient had an extra episode through stopping lithium then their prospects over the next year would be less good than if they had avoided this relapse. However, if there has previously been a good response to lithium then it is definitely worth going back to this treatment again after a relapse, and not shifting on principle to a different medication.

5.29 Why do manic depressives who are doing well on lithium stop taking it?

Of course the usual reasons (lack of efficacy and side-effects) apply not only to lithium but also to other long-term treatments and there are other associations with non-compliance (see Q 5.43) including personality factors and substance misuse.

OTHER LONG-TERM TREATMENTS

5.31 Is valproate a useful long-term treatment in bipolar illness?

Mania can be effectively treated with valproate (see Q 4.4). It relieves the symptoms of mania as effectively as any other treatment and because it is generally well tolerated the dose can be increased rapidly even in patients who have never taken it before. Valproate may be the best treatment to give to those who are in a mixed episode (a simultaneous combination of mania and depression–see Q 1.11).

5.33 Is there a difference between sodium valproate and valproate semi-sodium (Depakote)

Valproate semi-sodium is better tolerated by the stomach than other formulations though in fact the slow-release version of sodium valproate is also a well-tolerated drug. The fact that Depakote is particularly well tolerated can be very useful in the initial stages of the treatment of mania because the dose can be escalated rapidly. Dose for dose Depakote will produce a higher blood level than other formulations of valproate.

5.34 Is carbamazepine useful in the treatment of bipolar illness?

Several anticonvulsants have been tried in the treatment of manic depression and carbamazepine has been used extensively over the last 10 years for this indication. Carbamazepine does have a licence in the UK in the treatment of manic depressive illness unresponsive to lithium. Carbamazepine is an effective antimanic treatment and is also quite sedative, particularly when it is first given, which can be an additional benefit in the early treatment of mania. The usual starting dose is 200 mg twice a day increasing up to 1 g, although sometimes higher doses are needed. Some studies showed carbamazepine to be an effective longer term preventive treatment but recent research showed that it was a less effective treatment than lithium for standard manic depressive illness (Greil et al 1997). It still has a place in the acute and long-term treatment of manic depression but should not be used in preference to lithium. However, it can be a useful alternative if lithium is neither suitable nor effective. The study by Greil et al (1997) showed that it was not as good as lithium generally, but did suggest that it may be a better treatment for schizoaffective manic depression (see Q 1.15)

5.36 Does lamotrigine have a place in the long-term treatment of manic depression?

Recent studies on lamotrigine in manic depression have been very encouraging and it seems likely that this will prove to be a more frequently used and beneficial treatment (Calabrese et al 2003). One of the main problems in treating bipolar illness is that depression is often chronic, pervasive and disabling. Lamotrigine has been shown to be an effective antidepressant in bipolar illness with only a limited propensity for switching into mania. The usual treatment dose is 200-300 mg but it can only be very slowly increased up to this level (see Q 5.37). This means that it is difficult to use lamotrigine in very acute depression but it can still be very useful in tackling longer term depressive symptoms. It is likely that it also has some benefit in the prevention of depression though probably not in the prevention of mania. For this reason, for those patients who have predominantly a depressive picture it is useful to consider this treatment.

5.38 Have any other anticonvulsants been found to be helpful in manic depression?

Because some anticonvulsants do appear to be helpful in manic depression many have been tried but none can currently be recommended for use apart from in exceptional circumstances. It is relatively common to find in manic depression (which is such a changeable disorder) that there are initial reports of benefit with new treatments but careful controlled testing does not bear out these out. Trials of gabapentin are a good example of initial reports of success which turned out not to be confirmed. Lithium also tends to come out badly in initial comparisons because the patients who are tried on new treatments are usually those who are not getting on well and so are a preselected group of lithium non-responders. Lithium has stood the test of time and it will be interesting to see which of the currently used treatments are still recommended 40 years hence!

5.39 Should anyone be taking two drugs to prevent recurrence?

There is very little information currently about whether combinations of long-term treatment are better than monotherapy. It could be that actually we should be treating bipolars with combination treatment from early on as this may lead to a better outcome, but at the moment we just do not know (see Balance Trial http://www.psychiatry.ox.ac.uk/balance/index.html).

5.40 Are antipsychotics useful in the long term?

A few people with manic depression have very little insight and do not take regular oral medication and so, as a last resort, a depot antipsychotic is prescribed. It is likely that this does have some benefit but it would not be recommended unless other treatments were not suitable or effective.

5.42 Are there special considerations for long-term treatment with lithium in the elderly?

The same long-term treatments are as appropriate for the elderly as for other adults. Complications can arise with lithium treatment because renal function slowly decreases with age. Because lithium is a salt it is not metabolised by the body but is entirely excreted by the kidney (with a small amount lost through sweat). Before starting lithium in the elderly you need to be confident that renal function is adequate, usually by undertaking a creatinine clearance test. However, the only real test is to start a small dose of lithium and check the levels while monitoring for adverse effects. The dosage of lithium is almost invariably lower, usually starting at 200 mg at night rather than 400 mg. The eventual dose is often 400-600 mg, whereas younger adults usually take 800-1200 mg daily.

Side-effects of lithium (see Q 5.7) are more common in the elderly, but it is as effective in this age group as for others. Similar considerations are needed for other long-term medications, where doses usually need to be lower and side-effects are often more evident.

5.43 How can compliance with treatment be improved?

Some tablet packs have the days written on them to help, but this is unusual for older drugs like lithium. Pill boxes that are filled once a week and then have a slot for each morning and evening can be a good way of helping to take the right dose each time, especially in complex regimens, and also give a good record of what has been missed.

5.44 What is the key to understanding the factors limiting concordance?

How ill would you need to be or how often would relapses need to occur before you would consider taking this type of treatment?

How ill would you need to be or how often would relapses need to occur before you would consider taking this type of treatment?5.45 Can other specialist staff help in the long-term management of bipolar illness?

Community psychiatric nurses can offer a wide range of interventions, the most important of which is usually their experience of how others have coped with the illness and its treatment. This advice can be invaluable, particularly in helping people to rebuild their lives after a serious breakdown. They have local knowledge and can help to reconnect people in their communities when their confidence is low. CPNs have a broad knowledge of the course of the illness, the treatments and their side-effects, which can build confidence when the patient feels they are the only one to have ever been in this situation. They can help to liaise with general practitioners to ensure that prescriptions are available and any treatment monitoring is undertaken. They usually have a broad range of psychotherapeutic skills which can help patients to understand their condition and how it relates to their life and relationships.

Community psychiatric nurses can offer a wide range of interventions, the most important of which is usually their experience of how others have coped with the illness and its treatment. This advice can be invaluable, particularly in helping people to rebuild their lives after a serious breakdown. They have local knowledge and can help to reconnect people in their communities when their confidence is low. CPNs have a broad knowledge of the course of the illness, the treatments and their side-effects, which can build confidence when the patient feels they are the only one to have ever been in this situation. They can help to liaise with general practitioners to ensure that prescriptions are available and any treatment monitoring is undertaken. They usually have a broad range of psychotherapeutic skills which can help patients to understand their condition and how it relates to their life and relationships. Social workers traditionally help with the practicalities of benefits and accommodation but also offer support to families. They are usually familiar with legal issues, both with the compulsory detention and also more unusual matters (e.g. power of attorney). If residential care is needed then they are usually responsible for organising and financing this. Many also have skills in counselling and are a good source of advice on local community services. Some social service departments employ support workers who are able to help patients with practical day-to-day tasks such as shopping and organising bills as well as other activities (e.g. going to the swimming pool).

Social workers traditionally help with the practicalities of benefits and accommodation but also offer support to families. They are usually familiar with legal issues, both with the compulsory detention and also more unusual matters (e.g. power of attorney). If residential care is needed then they are usually responsible for organising and financing this. Many also have skills in counselling and are a good source of advice on local community services. Some social service departments employ support workers who are able to help patients with practical day-to-day tasks such as shopping and organising bills as well as other activities (e.g. going to the swimming pool). Occupational therapists are expert at helping those recovering from mental illness to regain their skills for daily living and focus them on how they use their time and head back into the workplace.

Occupational therapists are expert at helping those recovering from mental illness to regain their skills for daily living and focus them on how they use their time and head back into the workplace. Psychologists usually undertake specific psychotherapeutic interventions but are also able to assess intellectual and cognitive function; both to help diagnosis and to guide treatment (see Q. 5.46).

Psychologists usually undertake specific psychotherapeutic interventions but are also able to assess intellectual and cognitive function; both to help diagnosis and to guide treatment (see Q. 5.46).5.46 What psychotherapeutic approaches can help to prevent recurrence?

IDENTIFYING THE EARLY SYMPTOMS OF RELAPSE

Many patients recognise a pattern to their illness in that certain symptoms or behaviours occur before the major relapse actually hits. If this can be identified then a plan can be made in advance as to how best to react to these symptoms (Lam et al 2003). This may be as simple as to contact a doctor or nurse to get advice or starting to take some medication. However, the essence of this approach is taking on the responsibility for managing the illness, both in terms of prevention but also at an early stage before it spirals out of control. A simple approach would be to recognise that losing sleep but lying in in the morning is usually the start of a depression. This may be the trigger for checking that the medication is being taken regularly, stopping drinking alcohol and getting advice about whether to start an antidepressant.

REVIEWING THE PAST EXPERIENCES OF TAKING AND STOPPING MEDICATION

Another technique commonly used by psychotherapists is to help patients to look at the pattern of their illness in the past. It can sometimes be very obvious to others that whenever the patient has given up lithium it has been followed by a relapse. However, this can be surprisingly difficult for patients to recognise because relapses are usually attributed to changes in personal circumstance, life’s pressures or how others are behaving, and seem to be more likely explanations for mood changes. Reviewing the course of the illness can lead to a better understanding of the relationship of the illness to the variety of factors that can affect it and then lead to other solutions or at least experiments. For example this may lead to looking at taking a new medication as an experiment for 3 months. During this time the patient should keep a weekly record of mood and at the end of the period look at the record to make the judgement as to how helpful the treatment has been. This can be considerably more effective than just going on how they feel at the end of the period (see also Q 5.25).

5.47 How do I know if my lithium level is too high?

However, if you start to get new physical symptoms then you need to think whether these could be because the level is getting high. The first sign of high levels is stomach problems–feeling nauseous and getting diarrhoea. Stomach upsets are obviously quite common, but if you have one you need to think if this could be because the lithium level is too high. It is very easy to get an extra blood lithium level done and if you are getting stomach problems you should do this.

5.50What if I have missed a dose of lithium?

With other medicines the usual rule of thumb is if you take it once a day then if you miss a dose then you could take it within the next 12 hours. If it is twice a day then take it within the next 6 hours, otherwise leave it. Missing occasional doses once a week or so is unlikely to have much effect on the effectiveness of the treatment.